CHAPTER 44 SURGICAL ANATOMY OF THE ABDOMEN AND RETROPERITONEUM

The abdominal cavity and the retroperitoneum lie immediately adjacent to one another. Some organs such as the small bowel and the colon have portions within the abdominal cavity while other parts are within the retroperitoneum. Vascular structures such as the superior mesenteric artery and vein course through both body compartments as well. A thorough knowledge of the anatomy of both the abdomen and retroperitoneum is critical for a rational operative approach to torso injuries.

EXPLORING THE ABDOMEN

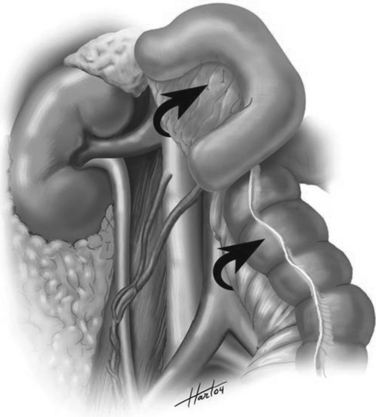

It is imperative to fully mobilize the spleen in order to be able to fully inspect all surfaces. This allows for intelligent decision making as to whether splenectomy or splenorrhaphy will be wise (Figure 1). All of the ligamentous attachments must be divided in order to get the spleen up to the anterior abdominal wall.

A similar strategy is important when inspecting the injured liver. The falciform ligament should be taken down all the way to the level of the vena cava. Both triangular ligaments must be completely incised. This leaves the liver suspended only on the hepatic veins and the portal structures. This allows the surgeon to rotate the liver up out of the deep recesses of the right upper quadrant, which is especially important when evaluating injuries to the posterior right lobe. In addition, one should evaluate whether sternotomy and/or right thoracotomy with takedown of the diaphragm will be needed for added exposure.

In more severe cases of liver injury, one may also consider the Heaney maneuver, which involves complete vascular isolation of the liver. In this technique, vascular clamps are placed on the cava, above and below the liver. When combined with the Pringle maneuver and/or supraceliac aorta clamping, this should provide for a relatively dry field in order to attempt to definitively repair the liver, and the hepatic venous injury. While this can be effective, it may be difficult to dissect out the suprahepatic vena cava in order to place a clamp, unless the diaphragm has been divided or the pericardium opened via a thoracotomy or sternotomy. The infrahepatic cava must be occluded distal to the junction of the renal vein. If the clamp is placed too low, flow from the renal vein into the cava will perpetuate bleeding and continue to make exposure extremely difficult. Occasionally, complete vascular isolation can be combined with a venous bypass circuit to allow for venous return to the heart (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Hepatic venous exclusion and venovenous bypass.

(Courtesy of ATOM, L. Jacobs, MD, Cine-Med, 2004.)

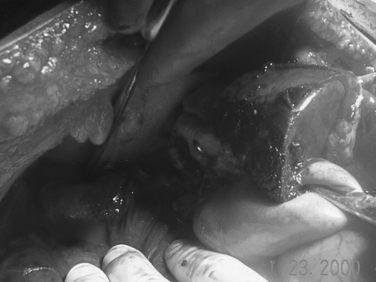

An intermediate solution to injuries with a hepatic vein component is manual compression medial to the injury. This should control all inflow to the injured segment. The injured liver can then be debrided. The hepatic vein can then be identified and ligated when pressure is relaxed. The more central hepatic arterial and portal venous branches can be ligated as well using the same temporary relaxation of hand held pressure (Figure 3).

The anterior portions of the duodenum and the head of the pancreas are in the abdomen. The posterior portion of the duodenum and the head of the pancreas are in the retroperitoneum. A full Kocher maneuver (incising the lateral peritoneal reflection and completely mobilizing the duodenum and pancreas) is necessary to evaluate both structures for injuries. The body of the pancreas lies within the lesser sac. It is necessary to widely open the lesser sac to examine the posterior stomach, as well as the anterior aspect of the body of the pancreas. This is best accomplished by dividing the gastrocolic omentum.

EXPLORING THE RETROPERITONEUM

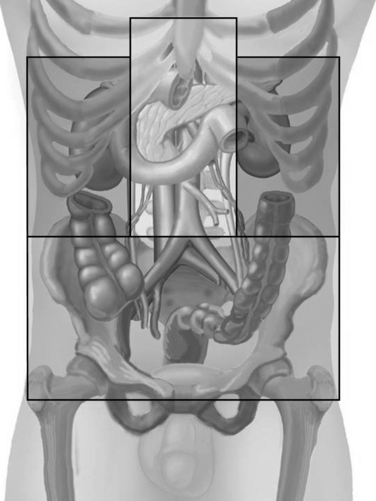

The retroperitoneum is generally divided into three zones (Figure 4). Zone one is the central portion of the retroperitoneum containing the aorta, vena cava, and the major branch vessels, as well as the superior mesenteric vein and splenic vein. Any retroperitoneal hematoma in zone one is generally explored.

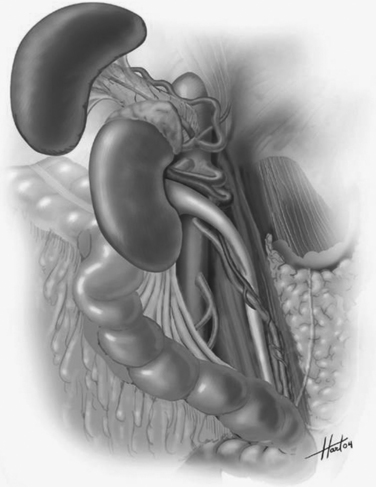

The so-called “Mattox maneuver” involves medial visceral rotation on the left side (Figure 5). The left colon is mobilized as described previously. This brings the surgeon down into the retroperitoneum. At the base of the mesentery, the surgeon will then encounter the aorta. The aorta can be followed up on its lateral margin at 3:00 quickly as there are no branches until one encounters the left renal artery and vein.

The Mattox maneuver involves mobilizing the kidney with the remainder of the viscera (see Figure 5). We generally prefer to leave the kidney in situ and mobilize it later if necessary. The splenic flexure must be completely mobilized into the lesser sac. The spleen and tail of pancreas can be mobilized which exposes the aorta up to the level of the hiatus. This is our preferred method of achieving aortic control at the level of the diaphragm. Often, the diaphragmatic crura come down lower than the surgeon expects. It may be necessary to divide the diaphragmatic fibers to control the supraceliac aorta.

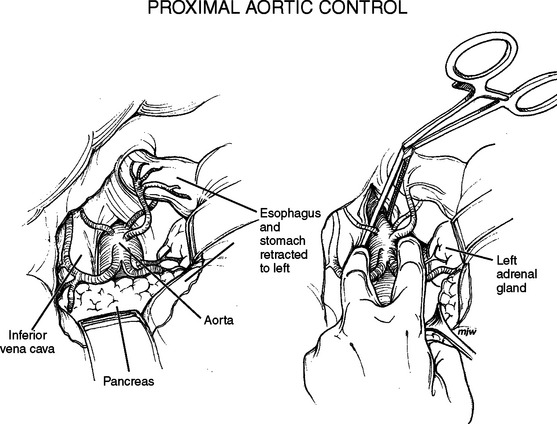

Supraceliac aortic control can also be obtained via a lesser sac approach (Figure 6). The lesser sac is opened widely by dividing the gastrohepatic ligament or lesser omentum, and then dissects down onto the superior aspect of the pancreas. The pancreas is mobilized and the esophagus and stomach bluntly dissected. This will bring the surgeon down onto the aorta. Again the diaphragmatic crura may have to be divided in order to gain good access to the aorta. With the aorta exposed, a cross-clamp can be applied.

A right-sided medial visceral rotation, the so called Cattel-Braasch maneuver, exposes the right-sided retroperitoneal structures (Figure 7). The right colon is mobilized in a technique exactly similar to what was described on the left side. Similarly, the dissection should be brought around the hepatic flexure and into the lesser sac. The duodenum and head of pancreas should be completely mobilized via a Kocher maneuver. This brings the surgeon down onto the inferior vena cava (IVC). The IVC can be controlled and traced up to the confluence of the left and right renal vein. There is a short suprarenal segment of the cava and then the vena cava becomes retrohepatic in location.

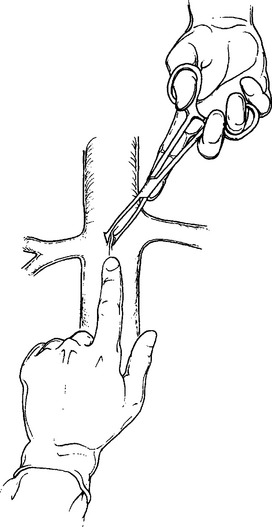

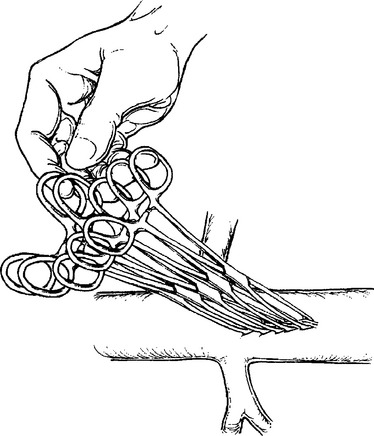

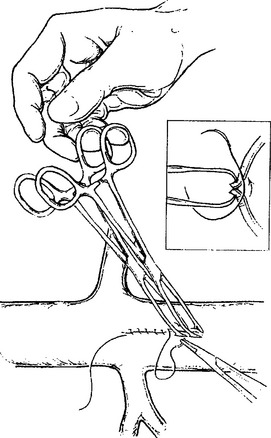

Retroperitoneal venous injuries can be among the most difficult to treat, particularly if located at the confluence of the vena cava and external iliac vein or in the juxtarenal IVC. Many techniques have been described for temporary vascular control including the use of sponge sticks, vascular clamps, and direct finger pressure to control bleeding. We have preferred the use of intestinal Allis clamps (Figures 8, 9, and 10). The vascular injury is first controlled with digital pressure and an Allis clamp is applied at the apex of the injury vessel. The clamps are then sequentially stacked for the length of the injury. The clamps can then be lifted. This allows for restoration of venous return to the heart. A decision can be made about ligation or repair. Vascular ligation can be accomplished by running a suture onto the clamp.

Occasionally, the pancreas can be mobilized up off the SMV and the injury isolated. There are many small branches off the SMV that must be individually ligated. If these are torn, the bleeding only becomes more difficult to control. Occasionally, identification of the location of an SMV injury is impossible, particularly if it is directly behind the pancreas or adjacent to the confluence of the splenic vein. In those cases, we generally divide the pancreas at the level of the SMV. This is done by gently inserting a finger behind the pancreas and mobilizing the pancreas off the SMV. A GIA stapler can be guided using a Penrose drain and the pancreas divided. This gives excellent exposure to the SMV proper and its junction with the splenic and portal veins. Virtually any injury can be identified and repaired. The distal pancreatic remnant can be resected later or inserted into a loop of jejunum depending on the surgeon’s preference.

Exposing the pelvic vasculature is a particular challenge (Figure 11). It is essential to identify the aorta proximally and be sure of its identification. Young patients in profound hemorrhagic shock can become intensely vasospastic. The common iliac artery may be mistaken for the external iliac artery or even the aorta. With the aorta and cava clearly identified and controlled, the surgeon must sequentially expose the common, external and hypogastric arteries. All of these should be individually controlled. The ureter runs through the retroperitoneum and into the pelvis at the confluence of the iliac arteries. This is a constant anatomic relationship. The ureter should be identified and protected during any pelvic exposure.

FUTURE CHALLENGES

The average general surgeon spends little time in the retroperitoneum, the lesser sac, or near the GE junction. Conditions that were once treated operatively are now treated nonoperatively because of better pharmacological agents and minimally invasive endoscopic techniques. General surgical procedures are increasingly being performed via a laparoscope. Finally, the average general surgery resident finishes his or her residency with fewer than 700 operative cases, a number far fewer than residents performed in the past. While community surgeons may opt to transfer moderately injured patients to a higher level of care, it simply is not feasible if the patient is hemodynamically unstable.

Asensio JA, Forno W, Roldan G, Petrone P, Rojo E, Ceballos J, Wang C, Costaglioli B, Romero J, Tillou A, Carmody I, Shoemaker WC, Berne TV. Visceral vascular injuries. Surg Clin North Am. 2002;82(1):1-20. xix

Feliciano DV. Management of traumatic retroperitoneal hematoma. Ann Surg. 1990;211:109-123.

Fry WR, Fry RE, Fry WJ. Operative exposure of the abdominal arteries for trauma. Arch Surg. 1991;126(3):289-291.

Golocovsky M. Retroperitoneal vascular trauma. In: Champion H, Robbs JV, Trunkey D, editors. Rob and Smith’s Operative Surgery: Trauma Surgery. 4th ed. London: Butterworths; 1998:555-557.

Hoyt D, Mileski W. Gallbladder and biliary tract. In: Carrico C, Thal E, Weigelt J, editors. Operative Trauma Management: An Atlas. New York: Appleton and Lange; 1998:144-155.

Scalea TM, Rodriguez A. Initial surgical care of the trauma patient. In: Corson JD, Williamson R, editors. Surgery. St. Louis: Mosby, 2001. Chapter 4

Wilson R, Walt A. Injuries to the liver and biliary tract. In: Wilson R, Walt A, editors. Management of Trauma: Pitfalls and Practice. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1996:457-458.