Chapter 98 Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation

Although atrial fibrillation (AF) is often regarded as an innocuous arrhythmia, it is associated with significant morbidity and mortality secondary to its detrimental sequelae: (1) palpitations resulting in patient discomfort and anxiety; (2) loss of atrioventricular (AV) synchrony, which can compromise cardiac hemodynamics and result in various degrees of ventricular dysfunction or congestive heart failure; (3) stasis of blood flow in the left atrium, increasing the risk of thromboembolism and stroke.1–10

The following section will briefly describe the historical aspects of surgery for AF.

Historical Aspects

Left Atrial Isolation Procedure

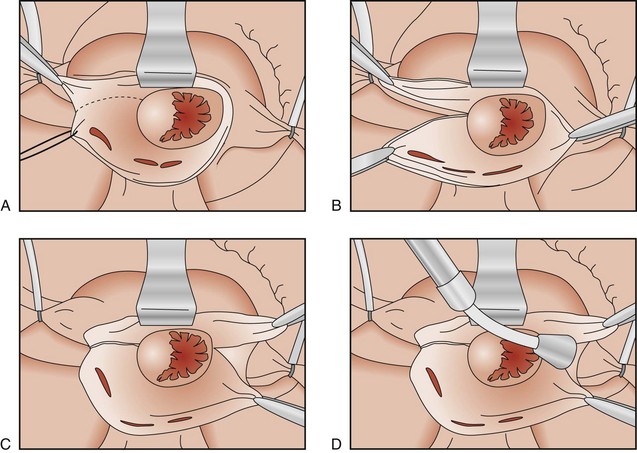

The first procedure designed specifically to eliminate AF was first described in 1980 in the laboratory of Dr. James Cox at Duke University. The left atrial isolation procedure, which confined AF to the left atrium, restored the remainder of the heart to sinus rhythm (Figure 98-1).11 This procedure was significant because it restored a regular ventricular rate without requiring a permanent pacemaker. Since the sinoatrial (SA) node, AV node, and internodal conduction pathways are located in the right atrium and the inter-atrial septum, the left atrial isolation procedure did not affect normal AV conduction. Isolating the left atrium allowed the right atrium and the right ventricle to contract in synchrony, providing a normal right-sided cardiac output. This effectively restored normal cardiac hemodynamics.

Catheter Ablation of the Atrioventricular Node–His Bundle Complex

In 1982, Scheinman and coworkers introduced catheter fulguration of the His bundle, a procedure that controlled the irregular cardiac rhythm associated with AF and other refractory supraventricular arrhythmias.12 This procedure electrically isolated the fibrillation to the atria. Unfortunately, ablating the bundle of His required permanent ventricular pacemaker implantation to restore a normal ventricular rate.

Corridor Procedure

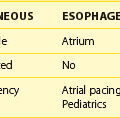

In 1985, Guiraudon et al developed the corridor procedure for the treatment of AF.13 This operation isolated a strip of atrial septum harboring both the SA node and the AV node, allowing the SA node to drive both ventricles. This procedure effectively eliminated the irregular heartbeat associated with AF, but both atria either remained in fibrillation or developed their own asynchronous intrinsic rhythm because they were isolated from the septal “corridor” (Figure 98-2). Furthermore, the atria were isolated from their respective ventricles, thereby precluding the possibility of AV synchrony. The corridor procedure was abandoned because it had no effect on the hemodynamic compromise or the risk of thromboembolism associated with AF.

Atrial Transection Procedure

In 1985, Dr. James Cox and associates described the first procedure that attempted to terminate AF.14 This was different from the earlier surgical procedures that only isolated or confined AF to a certain region of the atria. Using a canine model, Cox’s group found that a single long incision around both atria and down into the septum could terminate AF. This atrial transection procedure prevented the induction and maintenance of AF or atrial flutter in every canine that underwent the operation.15 Unfortunately, this procedure was not effective clinically and was abandoned.

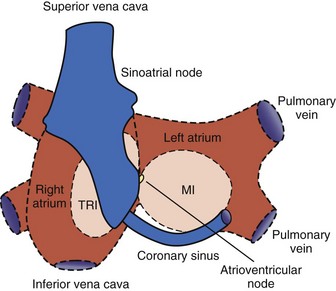

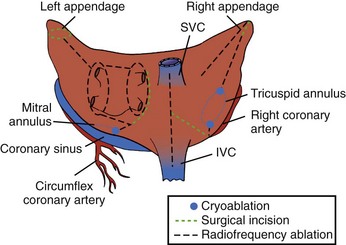

Development of the Cox-Maze Procedure

The Maze procedure was clinically introduced in 1987 by Dr. Cox after extensive animal investigation at Washington University in St. Louis.15–17 The Cox-Maze procedure was developed to interrupt any and all macro–re-entrant circuits that were felt to potentially develop in the atria, thereby precluding the ability of the atrium to flutter or fibrillate (Figure 98-3). Unlike earlier procedures, the Cox-Maze procedure successfully restored both AV synchrony and sinus rhythm, thus potentially reducing the risk of thromboembolism and stroke.18 The operation consisted of creating a myriad surgical incisions across both the right and left atria. These incisions were placed so that the SA could still direct the propagation of the sinus impulse throughout both atria. It allowed for most of the atrial myocardium to be activated, resulting in the preservation of atrial transport function in most patients.19

The original version, the Maze I procedure, was modified because of problems with late chronotropic incompetence and a high incidence of pacemaker implantations. The Maze II procedure, however, was extremely difficult to perform technically. It was soon replaced by the Maze III procedure, also known as the Cox-Maze III procedure today (Figure 98-4).20,21

The Cox-Maze III procedure—often referred to as the “cut-and-sew” Maze—became the gold standard for the surgical treatment of AF. In a long-term study of patients who underwent the Cox-Maze III procedure at the authors’ institution, 97% of the patients at late follow-up were free of symptomatic AF.22 These excellent results have been reproduced by other groups worldwide.23–25

The indications for surgery have been defined in a recent consensus statement.26 These presently include (1) all symptomatic patients with documented AF undergoing other cardiac surgical procedures, (2) selected asymptomatic patients with AF undergoing cardiac surgery in which the ablation can be performed with minimal risk in experienced centers, and (3) stand-alone AF, which should be considered for symptomatic patients with AF who prefer a surgical approach, have failed one or more attempts at catheter ablation, or are not candidates for catheter ablation.

In the authors’ opinion, relative indications for surgery were not included in the consensus statement. The first is a contraindication to long-term anticoagulation in patients with persistent AF and a high risk for stroke (CHADS score ≥2). Up to one third of patients with AF screened for participation in clinical trials of warfarin were deemed ineligible for chronic anticoagulation, mainly because of a perceived high risk of bleeding complications.27,28 In fact, patients on warfarin have twice the rate of intracerebral hemorrhage and mortality in a dose-dependent relationship.29 In one study, the annual rate of intracranial hemorrhage in anticoagulated patients with AF was 0.9% per year, and the overall major bleeding complications was 2.3% per year.28 The Cox-Maze procedure not only is able to eliminate AF in most patients but also amputates the left atrial appendage. The stroke rate following the procedure off anticoagulation has been remarkably low, even in patients with a CHADS score ≥2. At the authors’ institution, only 5 of 450 patients had a stroke after a mean follow-up of 6.9 ± 5.1 years. No difference in stroke rate was observed in those patients with CHADS scores above or below 2.30 This low risk of stroke following the Cox-Maze procedure has been noted in other series as well.18,31,32

Surgical treatment for AF with amputation of the left atrial appendage also should be considered in patients with chronic AF who have suffered a cerebrovascular accident despite adequate anticoagulation. These patients are at high risk of recurring neurologic events. Anticoagulation with warfarin reduces the risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes by over 60% in patients with AF but does not completely eliminate this serious complication.9,33 At the authors’ institution, 20% of patients who underwent the Cox-Maze III procedure had experienced at least one episode of cerebral thromboembolism that resulted in a significant temporary or permanent neurologic deficit prior to undergoing the operation.22 No late strokes occurred in this population, with 90% of patients off anticoagulation at last follow-up.22

In patients undergoing concomitant valve surgery, studies have shown that adding the Cox-Maze procedure can decrease the late risk of cardiac-related and stroke-related deaths.34,35 However, there have been no prospective or randomized studies demonstrating the survival or other benefits of adding a Cox-Maze procedure in patients with AF. The contraindication to a Cox-Maze procedure in this group would be in asymptomatic patients who have tolerated their AF well and have not had problems with anticoagulation and in whom adding the ablation would increase their surgical risk.

Surgical Ablation Technology

For ablation technology to successfully replace incisions, it must meet several criteria. (1) It must create linear ablation lines that reliably produce bi-directional conduction block. This is the mechanism by which incisions prevent AF, by either blocking macro–re-entrant or micro–re-entrant circuits or isolating trigger foci. The authors’ laboratory and others have shown that this requires a transmural lesion, as even small gaps in ablation lines can conduct both sinus and fibrillatory impulses.36,37 (2) The ablation device must be safe. This requires a precise definition of dose-response curves to limit excessive or inadequate ablation. The surgeon must also have knowledge of the effects of a specific ablation technology on surrounding vital cardiac structures such as the coronary sinus, coronary arteries, and valvular structures. (3) The ablation device should make AF surgery simpler and require less time to perform. This would require the device to create lesions rapidly, be simple to use, and have adequate length and flexibility. (4) The device should be adaptable to a minimally invasive approach. This would include the facility to insert the device through minimal access incisions or ports, and the device should be able to create epicardial transmural lesions on the beating heart. Currently, no device has met all of these criteria. The following sections will briefly summarize the current ablation technologies and their advantages and disadvantages.

Cryoablation

Currently, two commercially available sources of cryothermal energy are being used in cardiac surgery. The older technology, based on nitrous oxide, is manufactured by AtriCure (Cincinnati, OH). More recently, ATS Medical (Minneapolis, MN.) has developed a device based on argon. At 1 atmosphere of pressure, nitrous oxide is capable of cooling tissue to −89.5° C, while argon has a minimum temperature of −185.7° C. The nitrous oxide technology has a well-defined efficacy and safety profile and is generally safe except around the coronary arteries.38,39 The potential disadvantage of cryoablation, however, is the relatively long time that is needed to create lesions (1 to 3 minutes). Creating lesions on the beating heart is also difficult because of the “heat sink” of the circulating blood volume.40 Furthermore, if blood is frozen during epicardial ablation on the beating heart, it coagulates, creating a potential risk for thromboembolism.

Radiofrequency Energy

Radiofrequency (RF) energy, which has been used for cardiac ablation for many years in the electrophysiology laboratory, was one of the first energy sources to be applied in the operating room.41 RF energy uses alternating current in the range of 100 to 1000 kHz. This frequency is high enough to prevent rapid myocardial depolarization and the induction of ventricular fibrillation, yet low enough to prevent tissue vaporization and perforation. Resistive RF energy can be delivered by either unipolar electrodes or bipolar electrodes, and the electrodes can be either dry or irrigated. With unipolar RF devices, the energy is dispersed between the electrode tip and an indifferent electrode, usually the grounding pad applied to the patient. In bipolar RF devices, alternating current is passed between two closely approximated electrodes embedded in the jaws of a clamp. The lesion size depends on electrode-tissue contact area, the interface temperature, the current and voltage (power), and the duration of delivery. The depth of the lesion can be limited by char formation, epicardial fat, myocardial and endocavity blood flow, and tissue thickness.

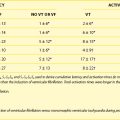

Numerous unipolar RF devices have been developed for ablation. These include both dry and irrigated devices and devices that incorporate suction. Although dry unipolar RF has been shown to create transmural lesions on the arrested heart in animals with sufficiently long ablation times, problems have occurred in humans. After 2-minute endocardial ablations during mitral valve surgery, only 20% of the in vivo lesions were transmural.42 Epicardial ablation on the beating heart has been even more problematic. Animal studies have consistently shown that unipolar RF is incapable of creating epicardial transmural lesions on the beating heart.43,44 Epicardial RF ablation in humans resulted in only 10% of the lesions being transmural.45 This deficiency of unipolar RF has been felt to be caused by the heat sink of the circulating blood.46 This has led some groups to examine the addition of both irrigation and suction to improve lesion formation. While these additions have improved the depth of penetration, a device capable of creating reliable transmural lesions on the beating heart is still not available.

To overcome this problem, bipolar RF clamps were developed. With bipolar RF, the electrodes are embedded in the jaws of a clamp to focus the delivery of energy. The electrodes are shielded from the circulating blood pool, and this allows for faster ablation times and limits collateral injury to tissue that is close to the electrodes. Bipolar ablation has been shown to be capable of creating transmural lesions on the beating heart, both in animals and humans, with short ablation times.47–49 Three companies (AtriCure; Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN; and Estech, San Ramon, CA) currently market bipolar RF devices.

Another advantage of bipolar RF energy is its safety profile. A number of clinical complications of unipolar RF devices that have been reported include coronary artery injuries, cerebrovascular accidents, and esophageal perforation leading to atrio-esophageal fistula.50–53 Bipolar RF technology has eliminated most of this collateral damage, and no injuries have been described with these devices despite extensive clinical use.

High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound

High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) is another modality that is applied clinically for surgical ablation (St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN). Ultrasound effectively ablates tissue via mechanical hyperthermia. When ultrasound waves are emitted from the transducer, the resulting wave travels through the tissue causing compression, refraction, and particle movement. This translates into kinetic energy and ultimately thermal coagulative tissue necrosis. HIFU produces rapid, high-concentration energy in a focused area and is reportedly able to create transmural epicardial lesions through epicardial fat in a short time.54

Another advantage of HIFU technology is its mechanism of thermal ablation. Unlike all other energy sources that heat or cool tissue by thermal conduction, HIFU ablates tissue by directly heating the tissue in the acoustic focal volume and is therefore much less affected by the heat sink of the circulating endocardial blood pool. A few clinical studies using HIFU have shown some encouraging results.54–57 However, the efficacy of HIFU devices to reliably create transmural lesions has not been independently verified. The fixed depth of penetration of these devices may be a major problem in pathologically thickened atrial tissue. Moreover, these devices are somewhat bulky and are expensive to manufacture.

Surgical Techniques

The Cox-Maze IV Procedure

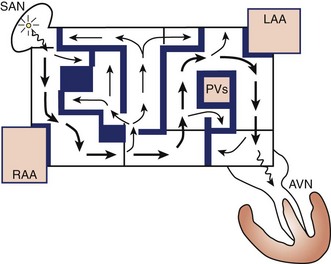

The original cut-and-sew Cox-Maze III procedure is only rarely performed today. At most centers, the surgical incisions have been replaced with lines of ablation using a variety of energy sources. At the authors’ institution, bipolar RF energy has been used successfully to replace most of the surgical incisions of the Cox-Maze III procedure. The current RF ablation–assisted procedure, termed Cox-Maze IV, incorporates the lesions as does Cox-Maze III (Figure 98-5).58 The authors’ clinical results have shown that this modified procedure has significantly shortened operative time while maintaining the high success rate of the original Cox-Maze III procedure.59

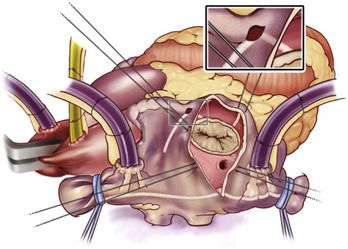

The right atrial lesion set is performed on the beating heart, as shown in Figure 98-6. A bipolar RF clamp is used to create most of the lesions. A unipolar device, either cryoablation or RF energy, is used to complete the ablation lines endocardially down to the tricuspid annulus because of the difficulty of clamping in this area.

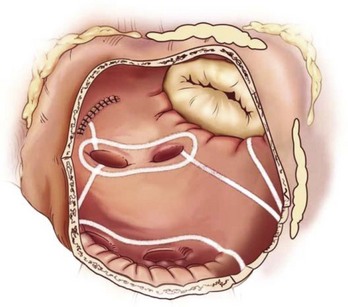

The left-sided lesion set (Figure 98-7) is performed via a standard left atriotomy on the arrested heart. The incision is extended inferiorly around the right inferior PV and superiorly onto the dome of the left atrium. Connecting lesions are made with the bipolar RF device into the left superior and inferior PVs and down toward the mitral annulus. The authors’ group has shown that isolating the entire posterior left atrium with ablation lines into both left PVs resulted in a better drug-free survival from AF at 6 and 12 months.60 A unipolar device, either cryoablation or RF, is used to connect the lesion to the mitral annulus and complete the left atrial isthmus line. The left atrial appendage is amputated, and a final ablation is performed through the amputated left atrial appendage into the one of the left PVs.

Left Atrial Procedures

Over the past decade, a number of new surgical procedures have been introduced in an attempt to cure AF. These procedures have generally involved some subset of the left atrial lesion set of the Cox-Maze procedure. The results have been variable and have ranged from 20% to 90% freedom from AF.50,61–68 They have been dependent on the technology used, the lesion set, and the patient population.

Pulmonary Vein Isolation

PV isolation (PVI) is an attractive therapeutic strategy because the procedure can be done without cardiopulmonary bypass and with minimally invasive techniques, using either an endoscopic approach or small incisions. On the basis of the original report of Hassaiguerre, it has been well documented that the triggers for paroxysmal AF originate from the PVs in the majority of cases.69 However, it is important to remember that up to 30% of triggers may originate outside the PVs.70 To increase efficacy, some investigators have added ablation of the ganglionic plexi (GP).71–73

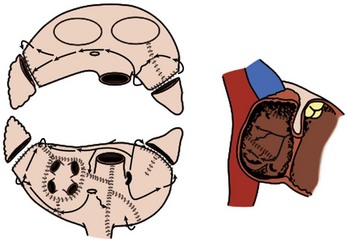

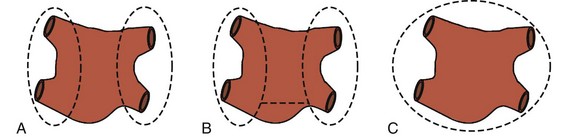

The PVs can be isolated separately or as a box (Figure 98-8). The most common technique, which will be described later, uses an endoscopic, port-based approach to minimize incisional size and pain for the patient. At the authors’ center, bipolar RF clamps are favored to isolate the PVs, but unipolar RF and HIFU devices have also been used.56,74 Patient preparation begins with double-lumen endotrachial intubation. A trans-esophageal echocardiogram is performed to confirm the absence of thrombus in the left atrial appendage. If a thrombus is found, the procedure is either aborted or converted to an open procedure, where the risk of systemic thromboembolism from left atrial clot can be minimized. External defibrillator pads are placed on the patient, and the patient is positioned with the right side turned upward 45 to 60 degrees and the right arm positioned above the head to expose the right axilla.

The procedure is not complete until the left atrial appendage has been addressed. Traditionally, this has been done by stapling across the base of the left atrial appendage with an endoscopic stapler. This has rarely proven to be technically difficult and can result in tears and bleeding.75 Several devices are being designed to address this difficulty. One such device with promise is a clip device, simply placed over the base of the left atrial appendage to exclude it (Figure 98-9). After ablation of the left PVs and exclusion of the left atrial appendage, the left side of the pericardium must be closed to avoid herniation of the heart.

Surgical Results

Cox-Maze Procedure

The Cox-Maze III procedure has had excellent long-term results. In the authors’ series at Washington University, 97% of 198 consecutive patients who underwent the procedure with a mean follow-up of 5.4 years were free from symptomatic AF. No difference was observed in the cure rates between patients undergoing a stand-alone Cox-Maze procedure and those undergoing concomitant procedures.22 Similar results have been obtained from other institutions around the world with the traditional cut-and-sew method.23,25,76

The authors’ results from patients who underwent the Cox-Maze IV procedure have been encouraging as well. In a prospective, single-center trial from their institution, 91% of patients at 6-month follow-up were free from AF.49,59 The Cox-Maze IV procedure has significantly shortened the mean cross-clamp times for a lone Cox-Maze from 93 ± 34 minutes for the Cox-Maze III to 47 ± 26 minutes for the Cox-Maze IV (P < .001), and from 122 ± 37 minutes for a concomitant Cox-Maze III procedure to 92 ± 37 minutes (P < .005) in those undergoing the Cox-Maze IV procedure concomitantly with another cardiac operation.49 A propensity analysis performed by the authors’ group has shown that no significant difference is present in the freedom from AF at 3, 6, or 12 months between the Cox-Maze III and Cox-Maze IV groups.77

The Cox-Maze IV procedure also worked just as well for patients with paroxysmal AF compared with persistent or longstanding persistent AF. The 6-month freedom from AF was 91% in the paroxysmal group compared with 88% in the persistent group (P = .53). Success with achieving a drug-free state was also similar.78 The authors’ present series consists of 263 consecutive patients undergoing the Cox-Maze IV procedure between January 2002 and June 2009. All patients have been monitored with electrocardiograms (ECGs) or prolonged monitoring. In the authors’ center, the rate of 12-month freedom from AF was 93%, with 78% of patients off all antiarrhythmic drugs. This center has had no intraoperative mortalities in 90 consecutive patients with lone AF who underwent this procedure.

Left Atrial Lesion Sets

A number of centers around the world have suggested that ablation be confined only to the left atrium to cure AF. This concept is supported by the fact that the majority of paroxysmal AF appears to originate around the PVs and the posterior left atrium. A left atrial lesion set typically involves PVI with a lesion to the mitral annulus as well as removal of the left atrial appendage. Numerous ablation technologies have been used to create these lesion sets with varying degrees of success.50,61–68

No randomized trials of bi-atrial ablation versus left atrial ablation only have been conducted in the surgical population. Because of this, the importance of the right atrial lesions of the traditional Cox-Maze procedure is difficult to determine. A meta-analysis of the published literature by Ad and colleagues revealed that a bi-atrial lesion set resulted in a significantly higher late freedom from AF when compared with a left atrial lesion set alone (87% vs. 73%; P = .05).79 This is not surprising, considering the results of intraoperative mapping of patients with AF. The authors’ group and others have shown that AF can originate from the right atrium in 10% to 50% of cases.80–82

Of the specific left atrial lesions of the Cox-Maze procedure, it is difficult to determine the precise importance of each particular ablation. All surgeons agree on the importance of isolating the PVs. Work from Gillinov et al also has shown the importance of the left atrial isthmus in a retrospective study.83 In a rare randomized trial, Gaita and coworkers examined PVI alone versus two alternative lesion sets, both of which included ablation of the left atrial isthmus. In this study, normal sinus rhythm at 2-year follow-up was only seen in 20% in the PVI group versus 57% in the other groups (P < .006).66 Finally, the authors’ group has shown that isolating the entire posterior left atrium significantly improved drug-free freedom from AF at 6 months (54% vs. 79%; P = .011) in a retrospective analysis of results.

Pulmonary Vein Isolation

The results of PVI alone have been variable and dependent on patient selection. In the first report of surgical PVI, Wolf and colleagues reported that 91% of patients undergoing video-assisted bilateral PVI and left atrial appendage exclusion were free from AF at 3-month follow-up.84 Edgerton et al reported on 57 patients undergoing PVI with GP ablation with more thorough follow-up and found 82% of their patients with paroxysmal AF to be free from AF at 6 months, with 74% off anti-arrhythmic drugs.85 Subsequent studies have shown encouraging results in patients with paroxysmal AF. In a study involving 21 patients with paroxysmal AF undergoing PVI with GP ablation, McClelland et al reported 88% procedural success, which was defined as freedom from AF at 1 year without antiarrhythmic drugs.72 A larger, single-center trial recently reported 65% success with a single procedure at 1 year in a series of 45 patients undergoing PVI with GP ablation, including patients with persistent and paroxysmal AF.86 A multiple-center trial reported 87% normal sinus rhythm in a more diverse patient population, including patients with longstanding, persistent AF; however, those patients with longstanding, persistent AF only had a 71% normal sinus rhythm rate.87

In patients with longstanding, persistent AF, the results have been worse. In a study from Edgerton and his group, only 56% of patients were free from AF at 6 months (35% off antiarrythmics).88 With concomitant procedures, the success rate of PVI is even lower. Of 23 patients undergoing mitral valve surgery or coronary revascularization with concomitant PVI, only half were free from AF at a follow-up of 57 ± 37 months.89 In the setting of mitral valve disease, Tada and colleagues reported 61% freedom from AF and only 17% freedom from antiarrythmic drugs in their series of 66 patients undergoing PVI.90

Ganglionated Plexus Ablation

Convincing experimental data have demonstrated that autonomic ganglia in GP play a role in the initiation and maintenance of AF.91,92 As a result, some authors have added GP ablation to PVI in the hope of increasing procedural efficacy. Some of the initial results of these trials have been encouraging. However, no randomized trials demonstrating the efficacy of adding GP ablation in the surgical setting have been conducted. In 2005, Scherlag and colleagues reported a study of GP ablation combined with catheter PVI in 74 patients with lone AF. After a relatively short median follow-up of 5 months, 91% of patients were found to be free from AF.92

However, the effects of vagal denervation are not clearly defined. Experimental evidence in the authors’ laboratory and others have demonstrated recovery of autonomic function as early as 4 weeks after GP ablation.93–95 It is worrisome that the reinnervation is not homogenous and may result in a more arrhythmogenic substrate. In a more recent report, Katritsis and colleagues used left atrial GP ablation to treat 19 patients with paroxysmal AF. Fourteen of these patients had recurrent AF during 1-year follow-up.96 The authors’ practice is not to perform GP ablation to treat AF. Furthermore, long-term follow-up data on the effects of GP ablation are lacking. Thus, GP ablation should be reserved only for centers participating in clinical trials.

Future Directions in Atrial Fibrillation Surgery

It is now known that multiple different possible mechanisms of AF exist and that multiple-point mapping is necessary to describe this complex arrhythmia.80–82,97,98 Epicardial activation sequence mapping has been the traditional gold standard for mapping of AF, but it is invasive and time consuming, which limits its clinical use.17 A newer noninvasive technique, electrocardiographic imaging (ECGI), offers a potentially useful way to describe the atrial activation sequence and determine mechanistic information from conscious patients.99 The technique uses body surface potentials, measured by surface electrodes, and anatomic data obtained through computed tomography (CT) scanning to indirectly calculate the surface potentials on the surface of the heart. This technique has been shown to work well for normal sinus rhythm and atrial flutter as well as for ventricular arrhythmias.100–102 Currently, the authors’ group is testing the technique in patients with persistent AF, in collaboration with Dr. Yoram Rudy, the developer of ECGI, at Washington University. The initial results are promising.100,103

The information acquired from ECGI can be analyzed to determine the activation sequence and frequency maps for individual patients noninvasively. Using these data, a strategy for designing patient-specific optimal lesion sets is being developed, taking into account the patient’s atrial geometry, conduction velocity, and refractory period.104 Initial lesions will be determined by a calculation of the critical area needed to maintain AF in the individual patient by using mechanistic information derived from activation data and anatomic data from the CT scan. It will also allow identification of focal sources that can then be isolated or ablated in the electrophysiological laboratory or operating room.

In instances where a specific mechanism of AF cannot be defined, the goal will be to create a lesion pattern that will prevent the atria from fibrillating. In this sense, the Cox-Maze III and IV procedures have failed to achieve this goal, with higher failure rates seen in patients with increasing left atrial size or longstanding AF.31,105,106 A recent study performed by the authors’ laboratory on a canine model found that the probability of maintaining AF is correlated with increasing atrial tissue areas, widths, and weights, as well as the length of the effective refractory period and the conduction velocity of the tissue.104 All of these data can be acquired noninvasively through ECGI. Using these data may allow surgeons to design operations customized for each patient on the basis of the mechanism of their arrhythmias and their specific atrial anatomy or electrophysiology.

Finally, the limitations of the current ablation devices have impeded the development of a truly minimally invasive procedure. Unfortunately, the creation of reliable transmural lines of ablation on the beating heart has been difficult. The probable reason is the heat sink of the circulating endocardial blood pool.46 Future advances may offer devices that overcome this limitation or introduce hybrid procedures in which surgeons and electrophysiologists work together to complete the lines of block.

In conclusion, the development of ablation technologies has dramatically changed the field of AF surgery. The replacement of the surgical incisions with linear lines of ablation has transformed a complex, technically demanding procedure into one accessible to the majority of surgeons. More importantly, these new ablation technologies have introduced the possibility of minimally invasive surgery for AF, which has prompted numerous efforts to develop simpler procedures that can be performed epicardially on the beating heart. Strong evidence that PVI may be effective in a subset of patients with paroxysmal AF is already available. With extended lesion sets, it may be possible to extend the efficacy of minimally invasive procedures to patients with persistent and longstanding AF. However, surgeons must remember that the Cox-Maze procedure is efficacious in these patients and can be performed using a small thoracotomy with acceptable success and low morbidity.32 Surgeons need to be careful in employing experimental procedures without informed consent from patients. It is also imperative that surgeons who are trying new procedures carefully follow their results and publish them in peer-reviewed journals. Surgeons performing AF ablation must adhere to the recently published guidelines for follow-up of patients and for determining success or failure after these procedures. As we learn more about the mechanisms of AF and develop improved preoperative diagnostic technologies capable of precisely locating the areas responsible for AF, it will become possible to tailor specific lesion sets and ablation modalities to individual patients, making the surgical treatment of AF more effective and available to a larger population of patients.

Aupperle H, Doll N, Walther T, et al. Ablation of atrial fibrillation and esophageal injury: Effects of energy source and ablation technique. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130(6):1549-1554.

Bando K, Kasegawa H, Okada Y, et al. Impact of preoperative and postoperative atrial fibrillation on outcome after mitral valvuloplasty for nonischemic mitral regurgitation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129(5):1032-1040.

Bando K, Kobayashi J, Kosakai Y, et al. Impact of Cox Maze procedure on outcome in patients with atrial fibrillation and mitral valve disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;124(3):575-583.

Cox JL. The minimally invasive Maze-III procedure. Oper Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;5:79.

Cox JL. The surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. IV. Surgical technique. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;101(4):584-592.

Cox JL, Boineau JP, Schuessler RB, Jaquiss RD, Lappas DG. Modification of the Maze procedure for atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation. I. Rationale and surgical results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;110(2):473-484.

Cox JL, Canavan TE, Schuessler RB, et al. The surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. II. Intraoperative electrophysiologic mapping and description of the electrophysiologic basis of atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;101(3):406-426.

Cox JL, Schuessler RB, D’Agostino HJJr, et al. The surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. III. Development of a definitive surgical procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;101(4):569-583.

Doll N, Pritzwald-Stegmann P, Czesla M, et al. Ablation of ganglionic plexi during combined surgery for atrial fibrillation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(5):1659-1663.

Edgerton JR, Edgerton ZJ, Weaver T, et al. Minimally invasive pulmonary vein isolation and partial autonomic denervation for surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(1):35-38. discussion 39

Feinberg MS, Waggoner AD, Kater KM, Cox JL, Lindsay BD, Perez JE. Restoration of atrial function after the Maze procedure for patients with atrial fibrillation. Assessment by Doppler echocardiography. Circulation. 1994;90(5 Pt 2):II285-92.

Gaynor SL, Diodato MD, Prasad SM, et al. A prospective, single-center clinical trial of a modified Cox Maze procedure with bipolar radiofrequency ablation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128(4):535-542.

Gillinov AM, Pettersson G, Rice TW. Esophageal injury during radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122(6):1239-1240.

Gillinov AM, Sirak J, Blackstone EH, et al. The Cox Maze procedure in mitral valve disease: Predictors of recurrent atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130(6):1653-1660.

Knaut M, Spitzer SG, Karolyi L, et al. Intraoperative microwave ablation for curative treatment of atrial fibrillation in open heart surgery—the MICRO-STAF and MICRO-PASS pilot trial. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;47(Suppl 3):379-384.

Kosakai Y. Treatment of atrial fibrillation using the Maze procedure: The Japanese experience. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;12(1):44-52.

Ninet J, Roques X, Seitelberger R, et al. Surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation with off-pump, epicardial, high-intensity focused ultrasound: Results of a multicenter trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130(3):803-809.

Scherlag BJ, Nakagawa H, Jackman WM, et al. Electrical stimulation to identify neural elements on the heart: Their role in atrial fibrillation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2005;13(Suppl 1):37-42.

Viola N, Williams MR, Oz MC, Ad N. The technology in use for the surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;14(3):198-205.

1 Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vaziri SM, et al. Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort. The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 1994;271(11):840-844.

2 Wolf PA, Benjamin EJ, Belanger AJ, et al. Secular trends in the prevalence of atrial fibrillation: The Framingham Study. Am Heart J. 1996;131(4):790-795.

3 Cairns JA. Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation trial. Circulation. 1991;84(2):933-935.

4 Hart RG, Halperin JL, Pearce LA, et al. Lessons from the Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation trials. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(10):831-838.

5 Sherman DG, Kim SG, Boop BS, et al. Occurrence and characteristics of stroke events in the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Sinus Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(10):1185-1191.

6 Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: The Framingham Study. Stroke. 1991;22(8):983-988.

7 Glader EL, Stegmayr B, Norrving B, et al. Large variations in the use of oral anticoagulants in stroke patients with atrial fibrillation: A Swedish national perspective. J Intern Med. 2004;255(1):22-32.

8 Steger C, Pratter A, Martinek-Bregel M, et al. Stroke patients with atrial fibrillation have a worse prognosis than patients without: data from the Austrian Stroke registry. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(19):1734-1740.

9 Risk factors for stroke and efficacy of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Analysis of pooled data from five randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154(13):1449-1457.

10 Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation: A major contributor to stroke in the elderly. The Framingham Study. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147(9):1561-1564.

11 Williams JM, Ungerleider RM, Lofland GK, Cox JL. Left atrial isolation: New technique for the treatment of supraventricular arrhythmias. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1980;80(3):373-380.

12 Scheinman MM, Morady F, Hess DS, Gonzalez R. Catheter-induced ablation of the atrioventricular junction to control refractory supraventricular arrhythmias. JAMA. 1982;248(7):851-855.

13 Guiraudon GM, Campbell CS, Jones DL, et al. Combined sinoatrial node atrioventricular node isolation: A surgical alternative to His bundle ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 1985;72(suppl 3):220.

14 Smith PK, Holman WL, Cox JL. Surgical treatment of supraventricular tachyarrhythmias. Surg Clin North Am. 1985;65(3):553-570.

15 Cox JL, Schuessler RB, D’Agostino HJJr, et al. The surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. III. Development of a definitive surgical procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;101(4):569-583.

16 Cox JL. The surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. IV. Surgical technique. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;101(4):584-592.

17 Cox JL, Canavan TE, Schuessler RB, et al. The surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. II. Intraoperative electrophysiologic mapping and description of the electrophysiologic basis of atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;101(3):406-426.

18 Cox JL, Ad N, Palazzo T. Impact of the Maze procedure on the stroke rate in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;118(5):833-840.

19 Feinberg MS, Waggoner AD, Kater KM, Cox JL, Lindsay BD, Perez JE. Restoration of atrial function after the Maze procedure for patients with atrial fibrillation. Assessment by Doppler echocardiography. Circulation. 1994;90(5 Pt 2):II285-92.

20 Cox JL, Boineau JP, Schuessler RB, Jaquiss RD, Lappas DG. Modification of the Maze procedure for atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation. I. Rationale and surgical results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;110(2):473-484.

21 Cox JL. The minimally invasive Maze-III procedure. Oper Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;5:79.

22 Prasad SM, Maniar HS, Camillo CJ, et al. The Cox Maze III procedure for atrial fibrillation: Long-term efficacy in patients undergoing lone versus concomitant procedures. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126(6):1822-1828.

23 McCarthy PM, Gillinov AM, Castle L, Chung M, Cosgrove D3rd. The Cox-Maze procedure: The Cleveland Clinic experience. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;12(1):25-29.

24 Raanani E, Albage A, David TE, Yau TM, Armstrong S. The efficacy of the Cox/Maze procedure combined with mitral valve surgery: A matched control study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;19(4):438-442.

25 Schaff HV, Dearani JA, Daly RC, Orszulak TA, Danielson GK. Cox-Maze procedure for atrial fibrillation: Mayo Clinic experience. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;12(1):30-37.

26 Calkins H, Brugada J, Packer DL, et al. HRS/EHRA/ECAS expert Consensus Statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: Recommendations for personnel, policy, procedures and follow-up. A report of the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) Task Force on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4(6):816-861.

27 Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Study. Final results. Circulation. 1991;84(2):527-539.

28 Bleeding during antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. The Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(4):409-416.

29 Rosand J, Eckman MH, Knudsen KA, et al. The effect of warfarin and intensity of anticoagulation on outcome of intracerebral hemorrhage. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(8):880-884.

30 Pet MA, Damiano RJJr, Bailey MS, Moon MR, Lawton JS, Rinne AW. Late stroke following the Cox-Maze procedure for atrial fibrillation: The impact of CHADS2 score on long-term outcomes. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6(5, Supplement 1):S14.

31 Gillinov AM, Sirak J, Blackstone EH, et al. The Cox Maze procedure in mitral valve disease: Predictors of recurrent atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130(6):1653-1660.

32 Ad N, Cox JL. The Maze procedure for the treatment of atrial fibrillation: A minimally invasive approach. J Card Surg. 2004;19(3):196-200.

33 Hart RG, Halperin JL. Atrial fibrillation and thromboembolism: A decade of progress in stroke prevention. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131(9):688-695.

34 Bando K, Kobayashi J, Kosakai Y, et al. Impact of Cox Maze procedure on outcome in patients with atrial fibrillation and mitral valve disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;124(3):575-583.

35 Bando K, Kasegawa H, Okada Y, et al. Impact of preoperative and postoperative atrial fibrillation on outcome after mitral valvuloplasty for nonischemic mitral regurgitation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129(5):1032-1040.

36 Inoue H, Zipes DP. Conduction over an isthmus of atrial myocardium in vivo: A possible model of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Circulation. 1987;76(3):637-647.

37 Melby SJ, Lee AM, Zierer A, et al. Atrial fibrillation propagates through gaps in ablation lines: Implications for ablative treatment of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5(9):1296-1301.

38 Gage AM, Montes M, Gage AA. Freezing the canine thoracic aorta in situ. J Surg Res. 1979;27(5):331-340.

39 Holman WL, Ikeshita M, Ungerleider RM, et al. Cryosurgery for cardiac arrhythmias: Acute and chronic effects on coronary arteries. Am J Cardiol. 1983;51(1):149-155.

40 Aupperle H, Doll N, Walther T, et al. Ablation of atrial fibrillation and esophageal injury: Effects of energy source and ablation technique. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130(6):1549-1554.

41 Viola N, Williams MR, Oz MC, Ad N. The technology in use for the surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;14(3):198-205.

42 Santiago T, Melo JQ, Gouveia RH, Martins AP. Intra-atrial temperatures in radiofrequency endocardial ablation: Histologic evaluation of lesions. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75(5):1495-1501.

43 Thomas SP, Guy DJ, Boyd AC, et al. Comparison of epicardial and endocardial linear ablation using handheld probes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75(2):543-548.

44 Hoenicke EM, SRJ, Patel H, et al. Initial experience with epicardial radiofrequency ablation catheter in an ovine model: Moving towards an endoscopic Maze procedure. Surgical Forum. 2000;51:79-82.

45 Santiago T, Melo J, Gouveia RH, et al. Epicardial radiofrequency applications: In vitro and in vivo studies on human atrial myocardium. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;24(4):481-486. discussion 486

46 Melby SJ, Zierer A, Kaiser SP, et al. Epicardial microwave ablation on the beating heart for atrial fibrillation: The dependency of lesion depth on cardiac output. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132(2):355-360.

47 Prasad SM, Maniar HS, Schuessler RB, Damiano RJJr. Chronic transmural atrial ablation by using bipolar radiofrequency energy on the beating heart. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;124(4):708-713.

48 Prasad SM, Maniar HS, Diodato MD, et al. Physiological consequences of bipolar radiofrequency energy on the atria and pulmonary veins: A chronic animal study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76(3):836-841. discussion 841–842

49 Gaynor SL, Diodato MD, Prasad SM, et al. A prospective, single-center clinical trial of a modified Cox Maze procedure with bipolar radiofrequency ablation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128(4):535-542.

50 Kottkamp H, Hindricks G, Autschbach R, et al. Specific linear left atrial lesions in atrial fibrillation: Intraoperative radiofrequency ablation using minimally invasive surgical techniques. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(3):475-480.

51 Gillinov AM, Pettersson G, Rice TW. Esophageal injury during radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122(6):1239-1240.

52 Laczkovics A, Khargi K, Deneke T. Esophageal perforation during left atrial radiofrequency ablation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126(6):2119-2120. author reply 2120

53 Damaria RG, Pagé P, Leung TK, et al. Surgical radiofrequency ablation induces coronary endothelial dysfunction in porcine coronary arteries. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;23:277-282.

54 Ninet J, Roques X, Seitelberger R, et al. Surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation with off-pump, epicardial, high-intensity focused ultrasound: Results of a multicenter trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130(3):803-809.

55 Groh MA, Binns OA, Burton HG3rd, et al. Epicardial ultrasonic ablation of atrial fibrillation during concomitant cardiac surgery is a valid option in patients with ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 2008;118(14 Suppl):S78-S82.

56 Mitnovetski S, Almeida AA, Goldstein J, et al. Epicardial high-intensity focused ultrasound cardiac ablation for surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. Heart Lung Circ. 2009;18(1):28-31.

57 Nakagawa H, Antz M, Wong T, et al. Initial experience using a forward directed, high-intensity focused ultrasound balloon catheter for pulmonary vein antrum isolation in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18(2):136-144.

58 Damiano RJJr, Gaynor SL. Atrial fibrillation ablation during mitral valve surgery using the atricure device. Oper Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;9(1):24-33.

59 Mokadam NA, McCarthy PM, Gillinov AM, et al. A prospective multicenter trial of bipolar radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation: Early results. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78(5):1665-1670.

60 Voeller RK, Bailey MS, Zierer A, et al. Isolating the entire posterior left atrium improves surgical outcomes after the Cox Maze procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135(4):870-877.

61 Sie HT, Beukema WP, Misier AR, et al. Radiofrequency modified maze in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing concomitant cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122(2):249-256.

62 Schuetz A, Schulze CJ, Sarvanakis KK, et al. Surgical treatment of permanent atrial fibrillation using microwave energy ablation: A prospective randomized clinical trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;24(4):475-480. discussion 480

63 Kondo N, Takahashi K, Minakawa M, Daitoku K. Left atrial maze procedure: A useful addition to other corrective operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75(5):1490-1494.

64 Knaut M, Spitzer SG, Karolyi L, et al. Intraoperative microwave ablation for curative treatment of atrial fibrillation in open heart surgery—the MICRO-STAF and MICRO-PASS pilot trial. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;47(Suppl 3):379-384.

65 Imai K, Sueda T, Orihashi K, et al. Clinical analysis of results of a simple left atrial procedure for chronic atrial fibrillation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71(2):577-581.

66 Gaita F, Riccardi R, Caponi D, et al. Linear cryoablation of the left atrium versus pulmonary vein cryoisolation in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation and valvular heart disease: Correlation of electroanatomic mapping and long-term clinical results. Circulation. 2005;111(2):136-142.

67 Fasol R, Meinhart J, Binder T. A modified and simplified radiofrequency ablation in patients with mitral valve disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129(1):215-217.

68 Benussi S, Nascimbene S, Agricola E, et al. Surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation using the epicardial radiofrequency approach: Mid-term results and risk analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74(4):1050-1056. discussion 1057

69 Haissaguerre M, Jais P, Shah DC, et al. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(10):659-666.

70 Lee SH, Tai CT, Hsieh MH, et al. Predictors of non-pulmonary vein ectopic beats initiating paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: Implication for catheter ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(6):1054-1059.

71 Doll N, Pritzwald-Stegmann P, Czesla M, et al. Ablation of ganglionic plexi during combined surgery for atrial fibrillation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(5):1659-1663.

72 McClelland JH, Duke D, Reddy R. Preliminary results of a limited thoracotomy: New approach to treat atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18(12):1289-1295.

73 Mehall JR, Kohut RMJr, Schneeberger EW, et al. Intraoperative epicardial electrophysiologic mapping and isolation of autonomic ganglionic plexi. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83(2):538-541.

74 Geuzebroek GS, Ballaux PK, van Hemel NM, et al. Medium-term outcome of different surgical methods to cure atrial fibrillation: Is less worse? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2008;7(2):201-206.

75 Healey JS, Crystal E, Lamy A, et al. Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion Study (LAAOS): Results of a randomized controlled pilot study of left atrial appendage occlusion during coronary bypass surgery in patients at risk for stroke. Am Heart J. 2005;150(2):288-293.

76 Arcidi JMJr, Doty DB, Millar RC. The Maze procedure: The LDS Hospital experience. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;12(1):38-43.

77 Lall SC, Melby SJ, Voeller RK, et al. The effect of ablation technology on surgical outcomes after the Cox-Maze procedure: A propensity analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133(2):389-396.

78 Aziz A, Bailey MS, Patel A, et al. The type of atrial fibrillation does not influence late outcome following the Cox-Maze IV procedure. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5(5):S318.

79 Barnett SD, Ad N. Surgical ablation as treatment for the elimination of atrial fibrillation: A meta-analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131(5):1029-1035.

80 Sahadevan J, Ryu K, Peltz L, et al. Epicardial mapping of chronic atrial fibrillation in patients: Preliminary observations. Circulation. 2004;110(21):3293-3299.

81 Nitta T, Ishii Y, Miyagi Y, Ohmori H, et al. Concurrent multiple left atrial focal activations with fibrillatory conduction and right atrial focal or reentrant activation as the mechanism in atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127(3):770-778.

82 Schuessler RB, Kay MW, Melby SJ, et al. Spatial and temporal stability of the dominant frequency of activation in human atrial fibrillation. J Electrocardiol. 2006;39(4 Suppl):S7-S12.

83 Gillinov AM, McCarthy PM, Blackstone EH, et al. Surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation with bipolar radiofrequency as the primary modality. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129(6):1322-1329.

84 Wolf RK, Schneeberger EW, Osterday R, et al. Video-assisted bilateral pulmonary vein isolation and left atrial appendage exclusion for atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130(3):797-802.

85 Edgerton JR, Jackman WM, Mack MJ. Minimally invasive pulmonary vein isolation and partial autonomic denervation for surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2007;20(3):89-93.

86 Han FT, Kasirajan V, Kowalski M, et al. Results of a minimally invasive surgical pulmonary vein isolation and ganglionic plexi ablation for atrial fibrillation: Single-center experience with 12-month follow-up. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2(4):370-377.

87 Beyer E, Lee R, Lam BK. Point: Minimally invasive bipolar radiofrequency ablation of lone atrial fibrillation: Early multicenter results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137(3):521-526.

88 Edgerton JR, Edgerton ZJ, Weaver T, et al. Minimally invasive pulmonary vein isolation and partial autonomic denervation for surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(1):35-38. discussion 39

89 Melby SJ, Zierer A, Bailey MS, et al. A new era in the surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation: The impact of ablation technology and lesion set on procedural efficacy. Ann Surg. 2006;244(4):583-592.

90 Tada H, Ito S, Naito S, et al. Long-term results of cryoablation with a new cryoprobe to eliminate chronic atrial fibrillation associated with mitral valve disease. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005;28(Suppl 1):S73-S77.

91 Po SS, Scherlag BJ, Yamanashi WS, et al. Experimental model for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation arising at the pulmonary vein-atrial junctions. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3(2):201-208.

92 Scherlag BJ, Nakagawa H, Jackman WM, et al. Electrical stimulation to identify neural elements on the heart: Their role in atrial fibrillation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2005;13(Suppl 1):37-42.

93 Mounsey JP. Recovery from vagal denervation and atrial fibrillation inducibility: Effects are complex and not always predictable. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3(6):709-710.

94 Oh S, Zhang Y, Bibevski S, et al. Vagal denervation and atrial fibrillation inducibility: Epicardial fat pad ablation does not have long-term effects. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3(6):701-708.

95 Sakamoto SI, Schuessler RB, Lee AM, et al. Vagal denervation and reinnervation after ablation of ganglionated plexi. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139(2):444-452.

96 Katritsis D, Giazitzoglou E, Sougiannis D, et al. Anatomic approach for ganglionic plexi ablation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102(3):330-334.

97 Berenfeld O, Mandapati R, Dixit S, et al. Spatially distributed dominant excitation frequencies reveal hidden organization in atrial fibrillation in the Langendorff-perfused sheep heart. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2000;11(8):869-879.

98 Nattel S, Shiroshita-Takeshita A, Brundel BJ, Rivard L. Mechanisms of atrial fibrillation: Lessons from animal models. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2005;48(1):9-28.

99 Ramanathan C, Ghanem RN, Jia P, et al. Noninvasive electrocardiographic imaging for cardiac electrophysiology and arrhythmia. Nat Med. 2004;10(4):422-428.

100 Damiano RJJr, Schuessler RB, Voeller RK. Surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation: A look into the future. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;19(1):39-45.

101 Ghanem RN, Jia P, Ramanathan C, et al. Noninvasive electrocardiographic imaging (ECGI): Comparison to intraoperative mapping in patients. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2(4):339-354.

102 Intini A, Goldstein RN, Jia P, et al. Electrocardiographic imaging (ECGI), a novel diagnostic modality used for mapping of focal left ventricular tachycardia in a young athlete. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2(11):1250-1252.

103 Schuessler RB, Damiano RJJr. Patient-specific surgical strategy for atrial fibrillation: Promises and challenges. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4(9):1222-1224.

104 Byrd GD, Prasad SM, Ripplinger CM, et al. Importance of geometry and refractory period in sustaining atrial fibrillation: Testing the critical mass hypothesis. Circulation. 2005;112(9 Suppl):I7-13.

105 Kosakai Y. Treatment of atrial fibrillation using the Maze procedure: The Japanese experience. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;12(1):44-52.

106 Gaynor SL, Schuessler RB, Bailey MS, et al. Surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation: Predictors of late recurrence. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129(1):104-111.