CHAPTER 52 Surgery of the lacrimal system

Background

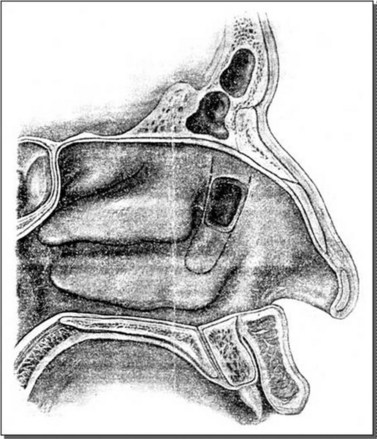

Lacrimal surgery existed in the Middle Ages for the treatment of dacryocystitis from a blocked nasolacrimal duct, albeit restricted to crude external drainage of abscess and extirpation of the lacrimal sac. It is not until the late 18th century that more modern techniques for draining the tear sac into the nose were introduced and it took some years for such dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) surgery to be widely available (Fig. 52.1).

Definitions

There are various abbreviations and different operations.

| 4 parts: dacro – cysto – rhino – stomy | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ancient Greek | Transliteration | Translation |

|

dakruon | tear |

|

kustis | bladder, sac |

|

rhis | nose |

|

stoma | mouth |

History of modern DCR

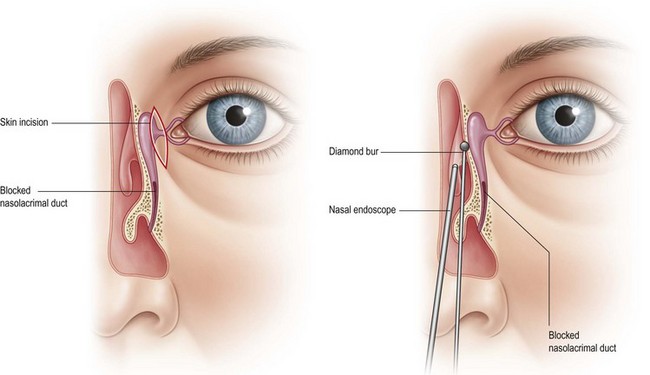

Endonasal approach lacrimal surgery has developed further in the last 15 years using endoscopic techniques and visualization with a Hopkins rigid nasal endoscope (Fig. 52.3). Endoscopic endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy (EE-DCR) is a primary treatment for nasolacrimal duct obstruction with a number of advantages compared with the traditional external approach. These advantages include avoidance of a cutaneous scar, direct visualization of nasal anatomy, and preservation of medial canthal tendon and pump function. The success rate for primary endonasal DCR surgery is comparable to the external approach.

Normal anatomy

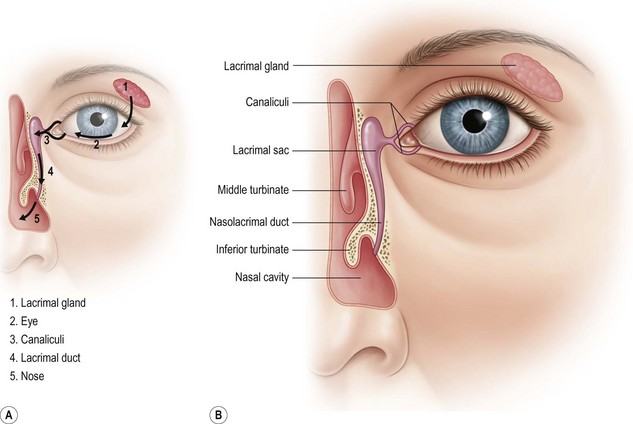

Tear drainage

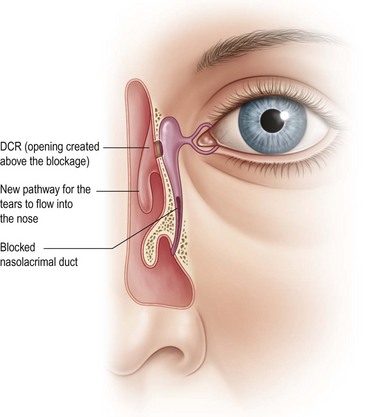

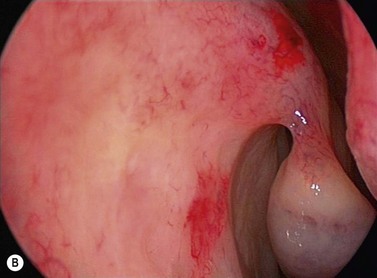

The tears normally drain through the puncta to the nose where they can be seen in the inferior meatus (Fig. 52.4).

Nasal anatomy

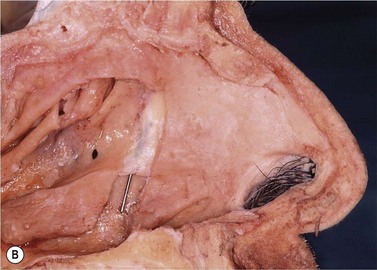

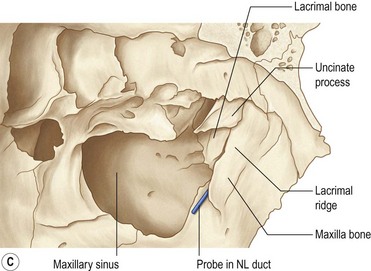

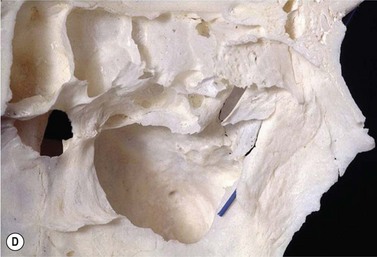

Soft tissue and bones of the lateral nasal wall

The main soft tissue structures of the lateral nasal wall are:

Etiology and assessment of watering eye

Blocked nasolacrimal duct in adults

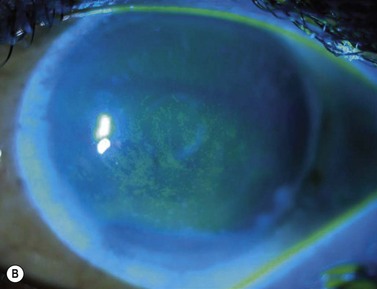

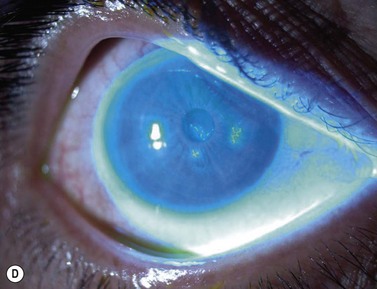

The causes of a watering eye include hypersecretion and epiphora. Causes of hypersecretion (conjunctivitis, keratitis, corneal foreign body, etc.) should be excluded (Fig. 52.7A–D). Surgery of the lacrimal system is for epiphora, which is an outflow problem cause by a stenosis or obstruction of the lacrimal excretory system or very poor functional drainage, as for instance may occur in facial nerve paralysis.

The periorbital area should be examined and a mucocoele, dacyocystitis (Fig. 52.8), and fistula from the lacrimal sac should be excluded. Eyelid position, particularly punctual apposition to the globe, should also be recorded.

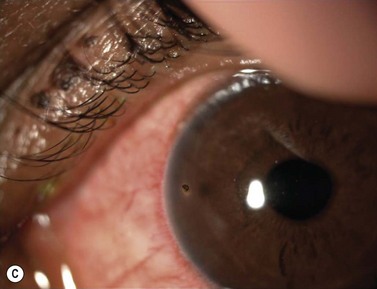

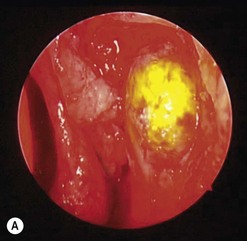

Canaliculitis is an often missed yet relatively common condition (Fig. 52.9). It is a simple diagnosis because the small swelling is medial to the punctum, which commonly has with some yellow discharge. It can be chronic and partially responsive to topical medication, with surgery the definitive treatment.

Surgery for epiphora in adults

Surgical options for blocked nasolacrimal duct obstruction in adults

Lesser options

External approach DCR surgery

External DCR steps

Endoscopic endonasal DCR surgery [see Clip 6.13]

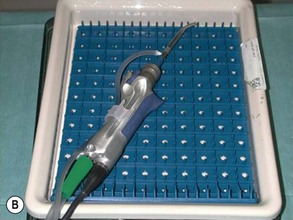

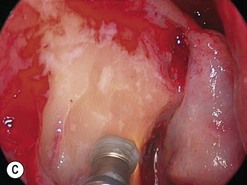

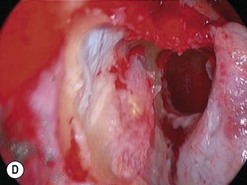

When mechanical tools with a high speed diamond burr are used, surgery is under a general anesthetic due to continual saline irrigation of the burr head and bone and simultaneous constant aspiration of saline (Fig. 52.10). The diamond DCR burr is 2.5 mm wide and at an angle of 20° to its handle. It is used at 12 000 revs. The serrated oscillating blade (microdebrider) is 3.5 or 4 mm diameter wide and used at oscillating speeds of 1500 up to 5000, taking care not to debride soft tissue towards the orbit, to avoid inadvertent orbital damage.

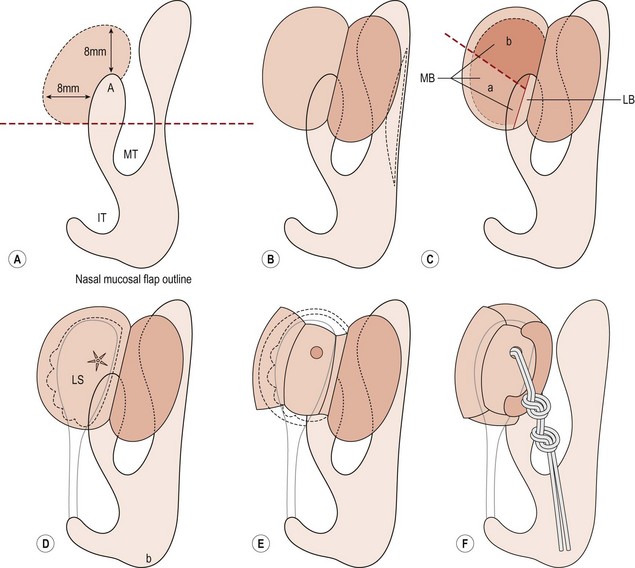

Endonasal endoscopic DCR steps (Figs 52.11–52.13)

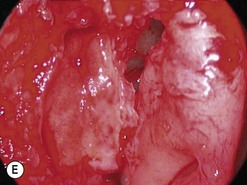

Inside the lacrimal sac

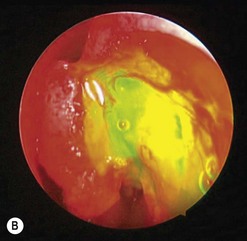

The addition of viscoelastic mixed with fluorescein 2% can be particularly helpful for defining the inside of the lacrimal sac as it provides color definition (Fig. 52.14).

Postoperative management after DCR surgery, external or endoscopic endonasal

Canaliculitis

Actinomycosis canaliculitis responds well to canalicular marsupialization (Fig. 52.16). If possible, try to open the canaliculus whilst preserving the punctual annular ring. The slit canaliculus can be subsequently re-sutured after intubation with a Mini-Monaka.

Re-do DCR [see Clips 6.15 and 6.16]

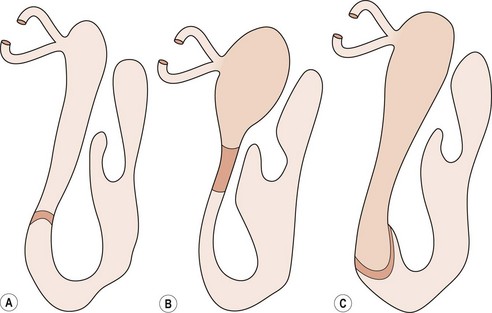

Failed DCR is usually due to a combination of factors including, most commonly, mucosal scarring across the ostium (membranous scarring) and/or a sump syndrome and/or inadequate bony removal (Figs 52.17 and 52.18). Endoscopic endonasal revision is a relatively simple procedure. Since the principle cause of failure is a scarred ostium, this must first be confirmed by probing and syringing of both the upper and lower canaliculus. Simultaneously, the endoscopic appearance of the ostium and surrounding structures is noted when a probe is in situ and it is possible to see if the membrane is densely scarred or thin. Some DCR ostiums fail because of chronic inflammation with granuloma formation within the ostium and sac remnant, which can be treated in a small number of cases with silver nitrate cautery. Usually the inflammation leads to scarring and need for subsequent re-do DCR.

Surgery in children

Congenital blocked nasaolacrimal duct in children

Management

Secondary endoscopic monitoring of syringe and probing ± nasolacrimal duct intubation

First the lacrimal system is syringed with fluorescein and saline then probed with a size 1 Bowman probe. The probe end is visualized at the floor of the nose and then removed. The system is syringed again (Fig. 52.20).

Intranasal cyst and amniocele in neonate

An intranasal cyst can cause difficulties in breathing and noisy breathing (Fig. 52.21). This can be picked up on taking a careful history. It can be associated with a congenital amniocele in an infant so there may be a small swelling over the lacrimal sac area.

Agarwal S. Endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy for acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J Laryngol Otol. 2009;123(11):1226-1228.

Anari S, Ainsworth G, Robson AK. Cost-efficiency of endoscopic and external dacryocystorhinostomy. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122(5):476-479.

Ben Simon GJ, Joseph J, Lee S, et al. External versus endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy for acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction in a tertiary referral center. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(8):1463-1468.

Boboridis K, Olver JM. Endoscopic endonasal assistance with Jones lacrimal bypass tubes. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 2000;31(1):43-48.

Brookes JL, Olver JM. Endoscopic endonasal management of prolapsed silicone tubes after dacryocystorhinostomy. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(11):2101-2105.

Caldwell GW. Two new operations for obstruction of the nasal duct. New York Med J. 1893:581-582.

Choussy O, Retout A, Marie JP, et al. Endoscopic revision of external dacryocystorhinostomy failure. Rhinology. 2010;48(1):104-107.

Codère F, Denton P, Corona J. Endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy: a modified technique with preservation of the nasal and lacrimal mucosa. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26(3):161-164.

Dolman PJ. Comparison of external dacryocystorhinostomy with nonlaser endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(1):78-84.

Eichhorn K, Harrison AR. External vs. endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy: six of one, a half dozen of the other? Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010;21(5):396-403.

Elmorsy SM, Fayk HM. Nasal endoscopic assessment of failure after external dacryocystorhinostomy. Orbit. 2010;29(4):197-201.

Fayers T, Laverde T, Tay E, et al. Lacrimal surgery success after external dacryocystorhinostomy: functional and anatomical results using strict outcome criteria. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;25(6):472-475.

Feretis M, Newton JR, Ram B, et al. Comparison of external and endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy. J Laryngol Otol. 2009;123(3):315-319.

Javate RM, Campomanes BSJr, Co ND, et al. The endoscope and the radiofrequency unit in DCR surgery. Ophthal Plast Reconst Surg. 1995;11(1):54-58.

Hartikainen J, Antila J, Varpula M, et al. Prospective randomized comparison of endonasal endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy and external dacryocystorhinostomy. Laryngoscope. 1998;108(12):1861-1866.

Konuk O, Kurtulmusoglu M, Knatova Z, et al. unsuccessful lacrimal surgery: causative factors and results of surgical management in a tertiary referral center. Ophthalmolgica. 2010;224:361-366.

Lee DW, Chai CH, Loon SC. Primary external dacryocystorhinostomy versus primary endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy: a review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;38(4):418-426.

Leibovitch I, Selva D, Tsirbas A, et al. Paediatric endoscopic endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy in congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244(10):1250-1254.

Leong SC, Macewen CJ, White PS. A systematic review of outcomes after dacryocystorhinostomy in adults. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2010;24(1):81-90.

Lim C, Martin P, Benger R, et al. Lacrimal canalicular bypass surgery with the Lester Jones tube. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;37(1):101-108.

Madge SN, Malhotra R, Desousa J, et al. The lacrimal bypass tube for lacrimal pump failure attributable to facial palsy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149(1):155-159.

Malhotra R, Wright M, Olver JM. A consideration of the time taken to do dacryo-cystorhinostomy (DCR) surgery. Eye (Lond). 2003;17(6):691-696.

Marr JE, Drake-Lee A, Willshaw HE. Management of childhood epiphora. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(9):1123-1126.

Mathew MR, McGuiness R, Webb LA, et al. Patient satisfaction in our initial experience with endonasal endoscopic non-laser dacryocystorhinostomy. Orbit. 2004;23(2):77-85.

McDonogh M, Meiring JH. Endoscopic transnasal dacryocystorhinostomy. J Laryngol Otol. 1989;103(6):585-587.

Metson R. Endoscopic surgery for lacrimal obstruction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;104(4):473-479.

Minasian M, Olver JM. The value of nasal endoscopy after dacryocystorhinostomy. Orbit. 1999;18(3):167-176.

Moore WM, Bentley CR, Olver JM. Functional and anatomic results after two types of endoscopic endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy: surgical and holmium laser. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(8):1575-1582.

Naik MN, Kelapure A, Rath S, et al. Management of canalicular lacerations: epidemiological aspects and experience with Mini-Monoka monocanalicular stent. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145(2):375-380.

Narioka J, Ohashi Y. Transcanalicular-endonasal semiconductor diode laser-assisted revision surgery for failed external dacryocystorhinostomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146(1):60-68.

Nemet AY, Fung A, Martin PA, et al. Lacrimal drainage obstruction and dacryocystorhinostomy in children. Eye (Lond). 2008;22(7):918-924.

Olver JM. The success rates for endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87(11):1431.

Olver JM. Tips on how to avoid the DCR scar. Orbit. 2005;24(2):63-66. Review

Repp DJ, Burkat CN, Lucarelli MJ. Lacrimal excretory system concretions: canalicular and lacrimal sac. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(11):2230-2235.

Spielmann PM, Hathorn I, Ahsan F, et al. The impact of endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR), on patient health status as assessed by the Glasgow benefit inventory. Rhinology. 2009;47(1):48-50.

Tsirbas A, Davis G, Wormald PJ. Mechanical endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy versus external dacryocystorhinostomy. Ophthal Plast Reconst Surg. 2004;20(1):50.

Welham RAN, Wulc AE. Management of unsuccessful lacrimal surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987;71:152-157.

Woog JJ, Kennedy RH, Custer PL, et al. Endonasal Dacryocystorhinostomy: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(12):2369-2377.

Wormald PJ. Powered endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy. Laryngoscope.. 2002;112:69-72.

Yoon SW, Yoon YS, Lee SH. Clinical results of endoscopic dacryocsytorhinostomy using a microdebrider. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2006;20(1):1-6.