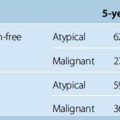

CHAPTER 23 Surgery of Convexity Meningiomas

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND CLASSIFICATION OF CONVEXITY MENINGIOMAS

Convexity meningiomas comprise 15% to 19% of all meningiomas.1,2 Generally, excision of these tumors is considered to be easy because of their accessibility. However, some difficulties might arise if they are located adjacent to eloquent areas or if there is no clear demarcation from brain tissue. To differentiate the localization of the tumor, convexity meningiomas are divided into seven subgroups according to the brain area they overlie: precoronal, coronal, postcoronal, parietal, prerolandic, temporal, and occipital. Most of the tumors (about 70%) are located anterior to the rolandic fissure. Before the advent of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and functional mapping, those subgroups and the coronal suture were helpful to rule out a localization in the neighborhood or within the central area. Further, the vicinity of the tumor close to eloquent areas such as the speech area in the frontal or parietal lobe was indicated by that grouping.

SYMPTOMS

Increased intracranial pressure causes general symptoms due to direct compression of the adjacent surface of the brain or a mass effect caused by the accompanying edema, especially in meningiomas that are increasing in size. As a result, patients may suffer from headache, organic psychosyndrome, and seizures. Moreover, the detailed neurologic deficits correspond to the adjacent eloquent areas. A contralateral palsy and motor seizures are caused by tumors surrounding the precentral cortex, and sensory deficits and Jacksonian seizures by tumors adjacent to the postcentral cortex. Seizures may be preceded by a motor or sensory aura and followed by a Todd’s palsy. In general, seizures are reported in 40.7% of patients exhibiting a convexity meningioma.3 Imaging is therefore important during the evaluation of an initial epileptic seizure.

As imaging techniques are evolving and the number of applications for screening purposes increasing, the diagnosis of incidental meningiomas is rising. Therefore, one should consider carefully the indication and time of surgery in this special case.4 The same is also true for elderly patients with regard to subtotal tumor removal and other treatment options such as pharmaco- or radiotherapy. In this group of patients, an accurate and detailed preoperative evaluation is essential.5,6

PREOPERATIVE DIAGNOSIS

As discussed in Chapters 13–16, computed tomography (CT), MRI, and digital subtraction angiography (DSA) are used for preoperative diagnosis.

In most instances CT is adequate for a correct diagnosis and demonstrates bony alternations such as hyperostosis and invasion. Normally, the tumors are hypodense on plain imaging and show intense and rapid contrast enhancement, and in 25% of all patients a calcification ranging from diffuse adherence to dense sclerosis is found.7

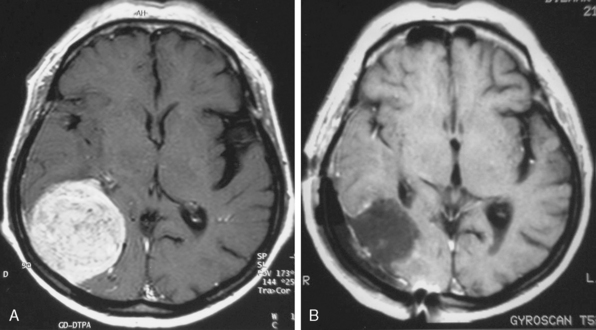

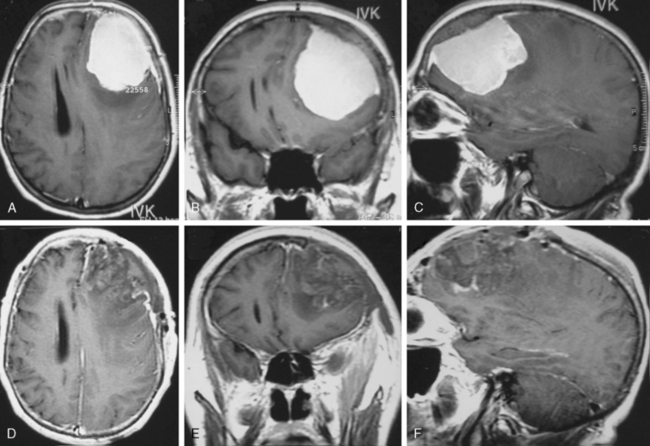

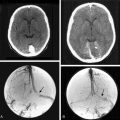

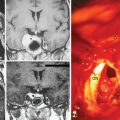

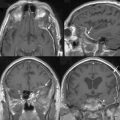

MRI is the current gold standard for a diagnosis. Excellent imaging of these tumors is provided with the use of gadolinium, as they show rapid, mostly homogeneous enhancement (Fig. 23-1). On non-contrast enhanced images they are iso- or hypointense compared to the brain. A so-called dura tail, which is caused by contrast enhancement of the surrounding meninges, is helpful for diagnosis. A rim of subarachnoid space around the tumor is an indicator for easy surgical excision and possible total removal.8,9 This well-defined boundary between tumor capsule and arachnoid membrane might be an indicator for a possible total resection of a tumor that is associated with a low risk of complications due to injury to the brain. Extrapial resection is essential to avoid any devascularization of the underlying cortex resulting in small cortical bleedings or a loss of function. If no cleavage plane is found in the tumor, vascularization derives from pial vessels. The latter can be shown via angiography and is also commonly associated with peritumoral edema and continuing tumor growth. In general, tumors exhibiting a diameter of less than 3 cm can be removed by an extrapial resection. In contrast, a larger tumor is associated with a higher risk pial vascularization, and a subpial resection therefore becomes necessary. The latter is also true if an irregular tumor border is found on T2-weighted images; however, there is no statistical significance in visible tumor–brain interface on T2-weighted images and a safe surgical plane for resection. In one third of patients no extrapial plane can be found and in 30% of them an adverse neurologic outcome occurs during subpial resection. Conversely, if an extrapial resection can be performed, an adverse outcome (Karnofsky < 80) will occur in only 25% of the patients. This is especially important if surgery is performed in eloquent areas, in which case it may be wise to leave some tumor remnants around the area to avoid neurologic deterioration.

A displacement of major arteries, a dislocation of sulci and gyri, especially in eloquent areas, and a peritumoral edema can also be visualized via MRI. Functional imaging can be used in combination with intraoperative, frameless neuronavigation. In some rare cases, cystic tumors can be found and the differential diagnosis from a metastatic lesion may be complicated.10

Embolization, performed by using polyvinyl alcohol, should take place 1 to 3 days before operation, even though one author proposes waiting for 7 to 9 days after surgery.11 Embolization is believed to be beneficial by reducing blood loss and leading to a shorter duration of the surgical procedure. However, in one study it was shown that intraoperative blood loss is reduced only if the tumor was embolized totally12 and no significant reduction of the duration of the surgical procedure or the extent of resection was found. Thus the debate about effectiveness continues. In superficial meningiomas, embolization is believed not to show any benefit; rather, there is an increased risk of brain swelling and bleeding within the tumor bed after the procedure, creating a need for emergency surgery.

ADVANCED TECHNOLOGIES

In the past, localization of the central sulcus was achieved by using somatosensory evoked potentials (SEPs), which are still used at present if functional neuronavigation is not available. While the median nerve is electrically stimulated, an atypical “phase reversal” is observed in consecutive four or more cortical leads that are displaced above the suspected central sulcus. However, the use of this method is fading due to improved accuracy and the broad availability of functional imaging and neuronavigation.13

INDICATION FOR SURGERY AND AIMS OF THE OPERATION

General Indications

There is no doubt that surgery is necessary if any neurologic deficits due to the size, extension, and/or increase of intracranial pressure occur. A perifocal edema that is mainly present in the special subgroup of secretory meningiomas shows high epileptogenic potential even if the tumors are small (Fig. 23-2). An antiedematous pretreatment is essential in those cases. From a cosmetic aspect and to avoid infections, surgery is also indicated for tumors that are mainly osteophytic and perforating the skin. Fortunately, such tumors are rare.

Incidental Findings

The increasing use of CT and MRI as screening methods reveals an increased number of incidental meningiomas. The finding rate of incidental meningiomas in autopsy series is approximately 2.3%. It is common opinion that those tumors occur throughout the entire life spans of the patients and exhibit only slow growing rates. Within the literature, absolute growing rates between 0.03 and 2.62 cm3/year and relative growing rates of 0.48% to 72.2% are reported. Further, tumors occurring in elderly patients exhibit slower growth patterns than those in younger individuals. If calcification or if an iso- or hypointense signal of the surrounding tissue in T2-weighted imaging is found, comparable growing rates are expected. Moreover, a mild correlation between tumor volume and absolute rate of growth was reported as well. Therefore MRI including volumetry should be performed every 3 to 6 months in younger and every 6 to 12 months in older patients. If the growth rate is greater than 1 cm3/year, surgical resection should be performed.14,15 The same is true for patients suffering from multiple meningiomas, which occur in about 8% of all cases.

Elderly Patients

In a study performed on elderly people (>70 years), neurologic deficit improved in 57.6%, was unchanged in 16.6%, and deteriorated in 18.2%, while 7.6% of the patients died during the first 30 days after surgery.16 There is a correlation between size of the tumor and duration of surgery and between the extent of perifocal edema and the neurologic outcome observed. The outcome in patients with a recurrent tumor was worse. A review of the literature revealed a mortality rate of 16% and a complication rate of 39% in meningioma surgery performed in patients 65 years of age or older.5 However, one author reported a mortality rate of 1.8% and a complication rate of 7%.5

The most important factor in determining whether to perform surgery or not seems to be the neurologic and general health status.17 Observation is justified if one or both are low and only mild tumor growth can be found. As a result, surgery was suggested in patients expressing criteria following American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) I or II and a Karnofsky index above 70. However, total resection was not the ultimate goal as there is a lower risk for significant tumor regrowth in those patients. In case there is any sign of growth, conservative treatment options such as radiotherapy and pharmacotherapy (hydroxyurea) are indicated.18,19

OPERATIVE PROCEDURE

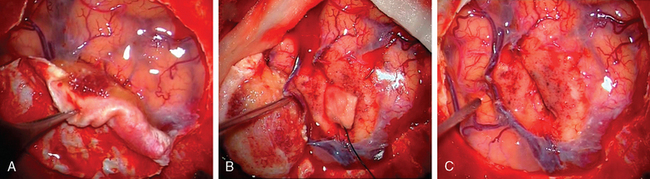

Dural Opening

Generally, the dural opening is performed 0.5 cm distant from the tumor margin, the dura is elevated with a sharp hook or a dura stitch, and the incision is carried out using a knife. Ultrasonography or neuronavigation might be helpful to define the tumor border. Afterwards, the dura incision is carried out circumferentially using blunt-tipped scissors and care has to be taken to avoid any damage of the draining veins that run around the tumor, especially in eloquent areas (Fig. 23-3). After resection of the tumor, the dura should be excised at least 5 to 10 mm distant from the tumor margin as tumor remnants could be shown to be present on histologic examinations, even in normal appearing dura20 in up to 40% of all cases. As a dura tail apparent in imaging may be caused by tumor invasion or hypervascularization, removal needs to be performed according to angiographic or radiographic contrast enhancement results or to the extent that the tumor tissue is visually judged within the dura. If there is any doubt about total resection, multiple histologic samples should be drawn. As sometimes an en plaque tumor or a spread of tumor cells within the arachnoid can occur, the dura has to be opened in an adequate size.21,22 To avoid recurrences, removal of the tumor remnants is superior to any cauterization of the dura edges.

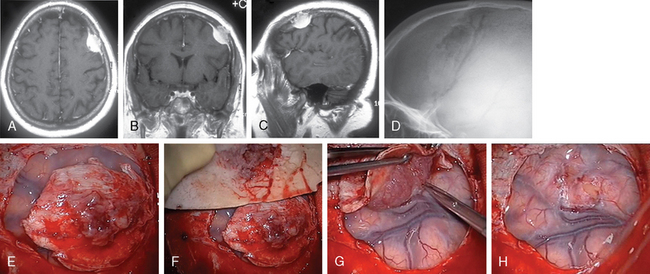

Tumor Excision

Depending on the size and localization of the tumor, the decision is made whether an en bloc resection is possible or an intracapsular debulking has to be performed. In the latter case, the blood supply has to be diminished first. Generally, this decision is to be made before starting microsurgical resection, which is considered standard by now. Further, the use of brain retractors and cotton pads must be avoided whenever possible and if necessary should only be transitory. Preparation is started with the intention to spare eloquent areas and localization of those areas is provided by SEPs or neuronavigation. As a result, in precentral meningiomas the resection is started from the frontal and in postcentral meningiomas from the posterior border. During preparation, the surgeon gently pulls the dura to visualize the border between arachnoidea and tumor. This cleavable plane is found in one half to two thirds of all patients, especially in those exhibiting no pial vessel parasitization.8 In case a tumor capsule is absent and the tumor is growing along vessels without clear demarcation, any preparation will be very difficult. Conversely, if a clearly defined capsule exists, it is very easy. Cautery forceps and microscissors are used to perform a blunt dissection following the cleavable plane extrapial. Those instruments are also used to visualize, coagulate, and cut adhesive bands of the arachnoidal layer and tiny tumor vessels. More aggressive resection becomes necessary in recurrent and malignant meningiomas that exhibit atypical features, in general. Especially in the latter type of meningiomas, the extent of surgery is to determine the course of the disease as the tumor might show frank invasion of the brain.

According to the surgeon’s experience, magnification provided by the microscope can be used from the beginning of preparation of the tumor borderline or during separation of the supplying vessels in the depth, especially if conducted in eloquent areas (Fig. 23-4). The use of the microscope has to be considered carefully, as an overestimation can be very time consuming and sometimes confusing while underestimation can lead to damage of the brain or important vessels.

If there is any risk of provoking neurologic deficits and a complete tumor removal cannot be achieved, remnants will be left in situ. In older patients, observation of the tumor growth and in younger patients adjuvant treatment strategies such as discussed above were applied, instead.23 The extent of tumor removal is graded according to Simpson:24

Depending on the grade of resection, follow-up or further treatment are performed. Generally speaking, in convexity meningiomas the prognosis is very good as there is an easy access to the tumor and a high opportunity to achieve a total resection. Complete resection, even if there is en plaque growth, will exclude recurrences in most of the cases. Regrowth is possible if microscopic residuals remain in situ or, as described in one study, within the arachnoid membrane.25 This might be due to a secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) which induces neovascularization and tumor regrowth.26 The higher pathologic grading of the tumor is not as much associated to incidence of recurrence than is a tumor remnant.27,28

POSTOPERATIVE CARE AND HANDLING OF COMPLICATIONS

In patients suffering from all types of meningiomas, the mortality and morbidity are somewhat higher in elderly patients (30-day mortality: 16%, complication: 39%). Especially in the former patients, a postoperative confusion is commonly found but a severe adverse event has to be ruled out. It must be emphasized that a fatal pulmonary embolism progresses in about 1.2 % of all patients after meningioma surgery.29

Even now, Gamma-Knife radiosurgery is supported as optional therapy in meningioma surgery, due to the higher risk of peritumorous changes, a higher rate of complication (43%) compared to surgery,30 and the risk of malignant transformation it should be performed only in older patients with a higher risk for anesthesia. This is important, as convexity meningiomas especially can be treated surgically with a low risk of mortality or morbidity.

[1] Maxwell R.E., Chou S.N. Convexiy meningiomas and general principles of meningioma surgery. Schmidek H.H., Sweet W.H., editors. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques, Indications and Methods, vol. 1. Grune & Stratton, New York, 1982;491.

[2] Giombini S., Solero C.L., Morello G. Late outcome of operations for supratentorial convexity meningiomas. Report on 207 cases. Surg Neurol. 1984;22:588.

[3] Lieu A.S., Howng S.L. Intracranial meningiomas and epilepsy: incidence, prognosis and influencing factors. Epilepsy Res. 2000;38:45.

[4] Yano S., Kuratsu J. Kumamoto Brain Research Group. Indications for surgery in patients with asymptomatic meningiomas based on an extensive experience. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:538.

[5] Black P., Kathiresan S., Chung W. Meningioma surgery in the elderly: a case-control study assessing morbidity and mortality. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1998;140:1013.

[6] Boviatsis E.J., Bouras T.I., Kouyiladis A.T., et al. Impact of age on complications and outcome in meningioma surgery. Surg Neurol. 2007;68:407.

[7] Osborne A. Meningiomas and other nonglial neoplasms. In: Diagnostic Neuroradiology 579. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1996.

[8] Sindou M.P., Alaywan M. Most intracranial meningiomas are not cleavable tumorsAnatomic-surgical evidence and angiographic predictability. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:476.

[9] Alvernia J.E., Sindou M.P. Preoperative neuroimaging findings as a predictor of the surgical plane of cleavage: prospective study of 100 consecutive cases of intracranial meningioma. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:422.

[10] Weber J., Gassel A.M., Hoch A., et al. Intraoperative management of cystic meningiomas. Neurosurg Rev. 2003;26:62.

[11] Kai Y., Hamada J., Morioka M., et al. Appropriate interval between embolization and surgery in patients with meningioma. Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23:139.

[12] Bendszus M., Rao G., Burger R., et al. Is there a benefit of preoperative meningioma embolisation? Neurosurgery. 2000;47:1306.

[13] Romstock J., Fahlbusch R., Ganslandt O., et al. Localisation of the sensimotor cortex during surgery for brain tumors: feasibility and waveform patterns of somatosensory evoked potentials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:221.

[14] Nakamura M., Roser F., Michel J., et al. The natural history of incidental meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:62.

[15] Yoneoka Y., Fujii Y., Tanaka R. Growth of incidental meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2000;142:507.

[16] Buhl R., Ahmad H., Behnke A., et al. Results in the operative treatment of elderly patients with intracranial meningioma. Neurosurg Rev. 2000;23:25.

[17] Lieu A.S., Howng S.L. Surgical treatment of intracranial meningiomas in geriatric patients. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 1998;14:498.

[18] Schrell U.M., Rittig M.G., Anders M., et al. Hydroxyurea for treatment of unresectable and recurrent meningiomas. II. Decrease in the size of meningiomas in patients treated with hydroxyurea. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:840.

[19] Hahn B.M., Schrell U.M., Sauer R., et al. Prolonged oral hydroxyurea and concurrent 3d-conformal radiation in patients with progressive or recurrent meningioma: results of a pilot study. J Neurooncol. 2005;74:157.

[20] Nakau H., Miyazawa T., Tamai S., et al. Pathological significance of meningeal enhanvement (flare sign) on meningiomas in MRI. Surg Neurol. 1997;48:584.

[21] vonDeimling A., Kraus J.A., Stangl A.P., et al. Evidence for subarachnoid spread in the development of multiple meningiomas. Brain Pathol. 1995;5:11.

[22] Stangl A.P., Wellenreuther R., Lenartz D., et al. Clonality of multiple meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:853.

[23] Kondziolka D., Mathieu D., Lunsford L.D., et al. Radiosurgery as definitive management of intracranial meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:53.

[24] Simpson D. The recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957;20:22.

[25] Kamitani H., Mauzawa H., Kanazawa I., et al. Recurrence of convexity meningiomas: tumor cells in the arachnoid membrane. Surg Neurol.. 2001;56:228.

[26] Yamasaki F., Yoshioka H., Hama S., et al. Recurrence of meningiomas. Cancer. 2000;89:1102.

[27] Ko K.W., Nam D.H., Kong D.S., et al. Relationship between malignant subtypes of meningioma and clinical outcome. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14:747.

[28] Maiuri F., Donzelli R., Mariniello G., et al. Local versus diffuse recurrence of meningiomas: factors correlated to the extent of recurrence. Clin Neuropathol. 2008;27:29.

[29] Kallio M., Sankila R., Hakulinen T., et al. Factors affecting operative and excess long-term mortality in 935 patients with intracranial meningioma. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:427.

[30] Kim D.G., Kim C.H., Chung H.T., et al. Gamma knife surgery for superficially located meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(Suppl.):255.