CHAPTER 87 Surgery for Tourette’s Syndrome

Tourette’s syndrome (TS) is a disorder in which individuals randomly but repeatedly exhibit stereotyped behavior (tics) of any part of the body, including the phonic (sound production) apparatus.1 Such movements may be simple or complex and may include socially inappropriate behavior. Tics occur many times per day in bouts. Affected individuals commonly describe an irresistible “urge” that is relieved when the tic occurs. Attempts to suppress expression of tics are usually only transiently successful and commonly result in rebound flurries.

According to the widely accepted Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV), the onset of TS occurs before the age of 18 years.2 The mean age at onset of symptoms is about 5 years, and the greatest tic severity occurs at approximately 10 years of age.3 TS was once thought to be rare, but studies in the past 20 years have documented prevalence rates as high as 1% to 2%,1 comparable to Parkinson’s disease. Males usually outnumber females by a factor of 3 to 4. TS occurs worldwide, and symptoms appear to be independent of culture or ethnic background. An association of TS with comorbid psychiatric disorders in pediatric patients is well described, including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), depression, and anxiety.1

Tic frequency and severity wax and wane with time and are reported to diminish by the age of 18 years. However, about half of all affected individuals continue to experience tic symptoms in adulthood.1 In a recent objective longitudinal study, 90% of individuals who had been videotaped as children still demonstrated tics when videotaped as adults, although a lower percentage reported that tics still occur.4 More than a quarter of these adult tic patients were disabled.4

Anatomic, Physiologic, and Pharmacologic Substrate of Tourette’s Syndrome

The etiopathology of TS is not yet clear. Genetic transmission is well documented,1,5 and a variety of genes have been explored. Some investigators have emphasized a possible role of infections and immune response in the development of TS and other “PANDAS” (pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infection),6 but this is not likely to be a major causative factor in most cases of TS.

The anatomic and physiologic substrate has long been believed to involve the basal ganglia and the corticostriatopallidothalamocortical (CSPTC) loop. By the late 1970s, it was apparent that antidopaminergic agents could suppress tics.7 The basal ganglia are a major target of the dopaminergic system projecting from the brainstem. Pathologic studies, anatomic imaging studies with magnetic resonance imaging, and functional neuroimaging studies consisting of functional magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography, and single-photon emission computed tomography have revealed various abnormalities of the basal ganglia and frontal cortex.8–10

Models of basal ganglia interconnections and function have been evolving11–14 in an attempt to explain basal ganglia dysfunction in a variety of neurological diseases, including parkinsonism, chorea, dystonia, and TS. The basal ganglia are the target of a large set of parallel pathways arriving from all parts of the cerebral cortex, and the output pathways remain essentially segregated in channels through the thalamus and back to the cerebral cortex.11,13 Our understanding has expanded to include more appreciation of specific interconnections between the basal ganglia and midline thalamic nuclei.

In current concepts of normal basal ganglia function, the system is optimized to select desired movement programs and suppress competing or unwanted movements.13,14 In hyperkinetic movement disorders such as chorea, elements of motor programs may be inappropriately selected in a random and nonpatterned fashion. In tic disorders, the inappropriate behavior is stereotyped and may be elemental (simple) or highly organized (complex), thus suggesting a type of dysfunction distinct from that of chorea.

Because the system contains not only motor but also prefrontal and limbic pathways serving cognitive and emotional functions, dysfunction of the basal ganglia commonly results in behavioral and affective disturbances. Within the striatal circuitry, abnormalities in the interaction of these systems may lead to inappropriate expression of specific tic behavior13,14 and may explain the high incidence of obsessive-compulsive symptoms and behavior in the TS population.

Although the association of obsessive and compulsive symptoms and behavior in TS is well described, their clinical manifestation differs from the symptoms and behavior observed in pure OCD.1 In TS, compulsions commonly involve checking, ordering, counting, repeating, and getting things “just right.” In primary OCD, obsessional themes tend toward contamination, dirt, germs, and fear of becoming ill, and compulsions relate to cleaning and washing. Patients with tic disorders commonly experience sensory premonitions before their tics, whereas in primary OCD, the premonitions are cognitive and autonomic. These differences suggest separate pathophysiologic origins of TS and OCD.

Medical and Behavioral Treatment of Tourette’s Syndrome

Pharmacologic treatment of TS has focused on dopamine receptor blockers (e.g., haloperidol, pimozide, fluphenazine, and other typical neuroleptics), presynaptic catecholamine-depleting agents (e.g., reserpine, tetrabenazine), or central α2-adrenergic receptor blockers (e.g., clonidine).14 Tics are rarely eradicated entirely; the goal of medication is to achieve maximal control with minimal side effects. About 13% to 22% of adult individuals with TS must continue to take medications for tics.4 Some adult patients remain symptomatic with clinically disabling tics despite maximal medical therapy.

Several specific behavioral techniques, as well as alternative treatments, have been investigated; however, these methods are incompletely studied or of limited efficacy.14 Some individuals benefit from local injections of botulinum toxin, but this strategy can be applied to only a very limited distribution of tics. For medically refractory individuals, there is no satisfactory alternative for controlling symptoms. It is in these cases that consideration is given to palliative surgical therapy.

Surgical Treatment of Tourette’s Syndrome

A variety of neurosurgical lesioning procedures have been used in an effort to palliate the symptoms of severe, medically refractory TS. Many deep brain targets have been explored, such as the frontal lobes, the cingulate gyrus, the anterior limb of the internal capsule, the limbic system, and the subthalamic zona incerta (reviewed by Temel and Visser-Vandewalle15). Some success has been achieved in amelioration of the psychiatric aspects of TS when present, especially those involving manifestations of OCD. In contrast, control of motor and sonic tics has been more variable and less significant. Risk for adverse effects related to these lesioning procedures has been high.

Other surgeons have stereotactically targeted the thalamus and basal ganglia for therapeutic lesioning, with more beneficial results. Cooper reported on 6 patients with severe motor tics who received significant benefit from staged bilateral ventrolateral (VL) thalamotomies.16 Hassler and Dieckmann reported on 15 patients who achieved excellent, durable clinical results after undergoing bilateral thermocoagulation of the rostral intralaminar nuclei and medial thalamic nuclei.17 de Divitiis and coauthors described 3 patients who underwent unilateral right-sided radiofrequency lesioning of the dorsal medial and intralaminar nuclei; 2 achieved complete remission and 1 had a minimal reduction in tics.18 Korzen and associates reported on 1 patient who experienced an excellent, sustained benefit after bilateral VL thalamotomy.19

Deep Brain Stimulation for Tourette’s Syndrome

Limited data are available regarding the efficacy of DBS in patients with TS. A case series of three patients was reported in which the ventral thalamus was targeted bilaterally.20 The first of these patients had been reported previously by Vandewalle and coworkers.21 These authors carefully considered the existing lesion-based reports and determined that the targets of Hassler and Dieckmann were most likely to result in a reduction in the occurrence of tics, and they targeted this thalamic region bilaterally. They reported a reduction in tic frequency of 70% to 90% with the stimulator on as compared with the stimulator-off state.

At University Hospitals Case Medical Center, after appropriate informed consent had been obtained, we performed a sentinel DBS implantation in 2004 that targeted the thalamic regions reported by Hassler and Dieckmann17 and Visser-Vandewalle and colleagues20 in a 30-year-old individual who had TS since before the age of 5 years. Tic frequency and severity were reduced dramatically, as measured by a video scoring procedure.22 That individual continues to enjoy minimal symptoms from tics several years after initial activation of his stimulators.

Clinical Trials of Deep Brain Stimulation for Tourette’s Syndrome

Based on the information available in 2005, our group conducted a pilot trial of thalamic DBS in five individuals.23 Thus far, no other randomized, sham-controlled, double-blinded, prospective clinical trials of DBS for TS have been conducted.

Preoperative and postoperative assessment tools included video recordings, the Yale Global Tourette Severity Scale (YGTSS, a validated standardized instrument),24 a tic diary incorporating the Tourette Syndrome Symptom Scale,25 two quality-of-life instruments (a visual analog scale and the Short Form Health Survey [SF-36]), and a neuropsychological battery.

A comparison of the modified Rush Video Rating Scale revealed a statistically significant difference among the four randomized states.26,27 This measure of tic frequency and severity (the primary outcome variable of the trial) was lower in the “both stimulators on” state than in the other states, especially the “both stimulators off” state. At 3 months’ follow-up, video and YGTSS scores were improved in three of the five subjects.23 At the 1-year follow-up, four of five reported improved tic symptoms and quality of life.28 One patient never benefited from stimulation.

Target Options for Deep Brain Stimulation for Tourette’s Syndrome

Fewer than 50 subjects who have undergone thalamic stimulation have been reported in articles or abstract form.20,22,23,29–33 Reported outcomes have generally been expressed in terms of tic frequency (usually video based) or a widely used rating scale, the YGTSS.24 Follow-up periods have ranged from a few months to more than 5 years. In successful cases, the reduction in tic frequency has been in the 70% to 100% range.

The precise thalamic target has not yet been established. The anchor point for the electrode (tip contact) is commonly reported to be intralaminar, in the centromedian-parafascicular (CM-Pf) nuclear complex.15 It is described as 5 mm lateral, 4 mm posterior, and 0 mm inferior to the midcommissural point.20 However, the active target in DBS is not necessarily the tip contact of the electrode because there are four electrodes to choose from over a span of 10.5 mm along the trajectory (labeled from tip to more proximal contacts as 0, 1, 2, 3). One may be able to identify the thalamic regions through which the electrode must pass (given a set of target coordinates and angles in the sagittal and coronal planes) and thereby determine possible sites of effective stimulation.

Visser-Vandewalle and coauthors did not report trajectory angles.20 However, according to Temel and Vandewalle,15 an electrode trajectory was chosen to allow the four contact points along the stimulating electrode to be positioned at or near the lesioning sites within the thalamus reported by Hassler and Dieckmann. Their active electrodes appear to span the entire range of possibilities, from the tip (3 mm beyond their target) to the fourth contact about 7.5 mm anterodorsal to the target along the trajectory. Houeto and associates used the tip and adjacent contact but induced adverse effects (contralateral contraction) with contacts 2 and 3, thus suggesting that the trajectory might have been through the internal capsule at that point.30 Ackermans and colleagues did not include sufficient detail to identify the trajectory that they used.31 Their active contacts were the tip and the adjacent contacts. The data available from Servello and associates are insufficient to interpret.32

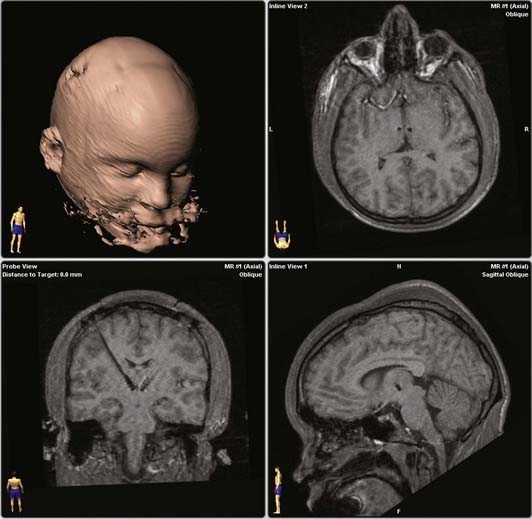

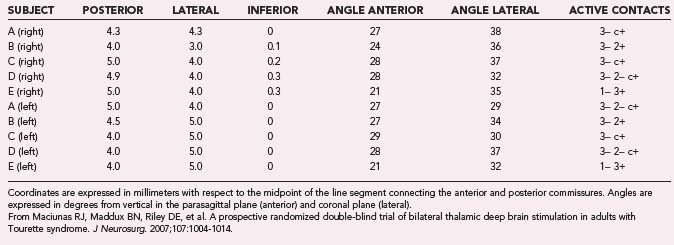

Cooper’s16 and Hassler and Dieckmann’s17 reports suggested that the most effective location for lesions was the VL thalamus. In our own trial, the electrode tip (contact 0) was placed at the published coordinates (on average, 4.3 mm lateral, 4.5 mm posterior, and 0.1 mm inferior to the midpoint of a line between the anterior and posterior commissures), and the trajectory (34 degrees in the lateral plane, 26 degrees anterior in the sagittal plane) included the VL thalamus (Fig. 87-1). The optimal response for each of the patients was achieved with either electrode 3 or 2, but never electrode 0.23 Individual data are presented in Table 87-1. Microelectrode recordings obtained during our procedures revealed a relatively silent zone around the target, but spontaneously firing neurons were plentiful along the trajectory in the regions that were ultimately used for stimulation (unpublished data). On the basis of the available data and our experience, we suspect that the actual stimulation zone is in the VL nucleus rather than the CM-Pf nuclear complex.

FIGURE 87-1 Representative electrode target and trajectory in a randomized trial of thalamic deep brain stimulation for Tourette’s syndrome.23 Upper right, axial slice at the tip electrode contact. Lower left, plane along the trajectories of bilateral electrodes. Lower right, parasagittal image demonstrating tip electrode contact. All magnetic resonance images are from the same patient.

TABLE 87-1 Target, Trajectories, and Active Electrode Contacts for Each Subject in a Randomized Trial of Thalamic Deep Brain Stimulation for Tourette’s Syndrome

Stimulation of the GPi has been reported in a handful of TS patients.30,31,34,35 As with thalamic stimulation, outcome measures have included tic frequency, YGTSS score, and other indices. Results have been comparable to those of thalamic stimulation.

Most authors state that their GPi target is the same as that used for other movement disorders such as Parkinson’s disease or dystonia, although one group explicitly targeted the “limbic pallidum.”30 The number and positions of the active electrodes vary, and it is not yet clear which pallidal target is most efficacious. It should be pointed out that for dystonic disorders treated by DBS (GPi target), the nuclear territory is relatively large, the amount of energy required to control symptoms is also large, and stimulator battery life is correspondingly shorter. This may be a disadvantage if patients require more frequent surgical replacement of the neurostimulators. Whether this situation applies to TS is not yet known.

Successful stimulation in the VL thalamus and GPi is consistent with an understanding of TS as a hyperkinetic movement disorder involving dysfunction of the CSPTC loops. Less success was apparent in a single case report of implantation of bilateral DBS electrode tips in the nucleus accumbens with contacts positioned along the anterior limb of the internal capsule. Tic reduction in this 37-year-old woman with self-injurious tic behavior but no psychiatric history was modest (≈20%),36 although the self-injurious behavior was significantly reduced. Profound effects on mood were reported with electrodes in these locations. The nucleus accumbens is part of the “limbic” basal ganglia and is more likely to be involved with emotional states than with movement per se. The nucleus accumbens and anterior limb of the internal capsule have been proposed as targets for the treatment of OCD.37 Although OCD is linked with TS, the available evidence suggests that TS is not a subset of OCD. Predictably, targeting of structures thought to be involved in obsessive-compulsive symptoms and behavior might not have as potent a direct effect on tic reduction as a target more embedded in the motor circuits. This group reported better efficacy for tic control after the same individual underwent surgery again to position leads in the thalamus bilaterally.33

Adverse Effects

Limited data are available concerning the adverse effects of DBS in patients with TS, and few serious or lasting adverse effects have been reported. In our trial,23 one subject experienced a brief psychosis at the end of the randomized evaluation period and was hospitalized for a short time. This was thought to have been precipitated by a major loss in life, and in follow-up he has remained stable and is in fact quite functional, with no recurrence of the psychosis. Neuropsychological measures demonstrated a nonsignificant trend toward decreased verbal fluency. Two of three patients reported by Visser-Vandewalle and coauthors experienced changes in sexual behavior.20 Ackermans and coworkers reported a vertical gaze palsy related to hemorrhage.38

Future Directions

As contributions of case studies and series have begun to mount, some authors have proposed standards for patient selection and the design and conduct of DBS trials for TS.39,40 The natural history of TS should be kept in mind, particularly the common observation that severity fades after adolescence. Whether pediatric intervention should be attempted is an issue not yet settled and should be carefully considered.41 The optimal timing of surgical intervention in adults is unknown. In any case, most investigators agree that the severity of the disorder and failure of nonsurgical treatment should be well established in any individual contemplating this procedure.

DBS is emerging as a promising treatment of TS in carefully selected individuals. Several case studies and series have demonstrated efficacy in patients in whom medical treatment has failed. Although the only double-blinded clinical trial to date has not included a large number of patients, the benefits of stimulation were significant and persistent.23,28 Validation in larger studies in which optimal targeting and stimulation parameters are addressed and risk factors for failure of therapy are identified are necessary.

Ackermans L, Temel Y, Cath D, et al. Deep brain stimulation in Tourette’s syndrome: two targets? Mov Disord. 2006;21:709-713.

Diederich NJ, Kalteis K, Stamenkovic M, et al. Efficient internal pallidal stimulation in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: a case report. Mov Disord. 2005;20:1496-1520.

Houeto JL, Karachi C, Mallet L, et al. Tourette’s syndrome and deep brain stimulation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:992-995.

Leckman JF, Zhang H, Vitale A, et al. Course of tic severity in Tourette syndrome: the first two decades. Pediatrics. 1998;102:14-19.

Maciunas RJ, Maddux BN, Riley DE, et al. A prospective randomized double-blind trial of bilateral thalamic deep brain stimulation in adults with Tourette syndrome. J Neurosurg. 2007;107:1004-1014.

Mink JW. Basal ganglia dysfunction in Tourette syndrome: a new hypothesis. Pediatr Neurol. 2001;25:190-198.

Mink JW, Walkup J, Frey KA, et al. Patient selection and assessment recommendations for deep brain stimulation in Tourette syndrome. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1831-1838.

Okun MS, Fernandez HH, Foote KD, et al. Avoiding deep brain stimulation failures in Tourette Syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:111-112.

Robertson MM. Tourette syndrome, associated conditions, and the complexities of treatment. Brain. 2000;123:425-462.

Servello D, Porta M, Sassi M, et al. Deep brain stimulation in 18 patients with severe Gilles de la Tourette syndrome refractory to treatment: the surgery and stimulation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:136-142.

Shahed J, Poysky J, Kenney C, et al. GPi deep brain stimulation for Tourette syndrome improves tics and psychiatric comorbidities. Neurology. 2007;68:159-160.

Shields DC, Cheng ML, Flaherty AW, et al. Microelectrode-guided deep brain stimulation for Tourette syndrome: within-subject comparison of different stimulation sites. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2008;86:87-91.

Temel Y, Visser-Vandewalle V. Surgery in Tourette syndrome. Mov Disord. 2004;91:3-14.

Visser-Vandewalle V, Temel Y, Boon P, et al. Chronic bilateral thalamic stimulation: a new therapeutic approach in intractable Tourette syndrome. A report of three cases. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:1094-1100.

1 Robertson MM. Tourette syndrome, associated conditions, and the complexities of treatment. Brain. 2000;123:425-462.

2 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

3 Leckman JF, Zhang H, Vitale A, et al. Course of tic severity in Tourette syndrome: the first two decades. Pediatrics. 1998;102:14-19.

4 Pappert EJ, Goetz CG, Louis ED, et al. Objective assessments of longitudinal outcome in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Neurology. 2003;61:936-940.

5 Leckman JF, Peterson BS, King RA, et al. Phenomenology of tics and natural history of tic disorders. Adv Neurol. 2001;85:1-14.

6 Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Garvey M, et al. Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections: clinical description of the first 50 cases. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:264-271.

7 Singer HS, Butler IJ, Tune LE, et al. Dopaminergic dysfunction in Tourette syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1982;12:361-366.

8 Swerdlow N, Young A. Neuropathology in Tourette syndrome. CNS Spectr. 1999;4:65-74.

9 Peterson BS. Neuroimaging studies of Tourette syndrome: a decade of progress. Adv Neurol. 2001;85:179-196.

10 Gerard E, Peterson BS. Developmental processes and brain imaging studies in Tourette syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55:13-22.

11 Alexander GE, DeLong MR, Strick PL. Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1986;9:357-381.

12 Albin RL, Young AB, Penney JB. The functional anatomy of basal ganglia disorders. Trends Neurosci. 1989;12:366-375.

13 Mink JW. Basal ganglia dysfunction in Tourette syndrome: a new hypothesis. Pediatr Neurol. 2001;25:190-198.

14 Leckman JF. Tourette syndrome. Lancet. 2002;360:1577-1586.

15 Temel Y, Visser-Vandewalle V. Surgery in Tourette syndrome. Mov Disord. 2004;19:3-14.

16 Cooper IS, editor. Involuntary Movement Disorders. New York: Harper and Row. 1969:274-279.

17 Hassler R, Dieckmann G. Relief of obsessive-compulsive disorders, phobias, and tics by stereotactic coagulations of the rostral intralaminar and medial-thalamic nuclei. In: Laitinen LV, Livingston K, editors. Surgical Approaches in Psychiatry. Proceedings of the 3rd International Congress of Psychosurgery, Cambridge, UK. Lechworth: Garden City Press; 1973:206-212.

18 de Divitiis E, D’Errico A, Cerillo A. Stereotactic surgery in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1977;24(suppl):73.

19 Korzen AV, Pushkov VV, Khantonor RA. [Stereotaxic thalamotomy in the combined treatment.]. Zh Neuropath Psikhiatr. 1991;3:100-101.

20 Visser-Vandewalle V, Temel Y, Boon P, et al. Chronic bilateral thalamic stimulation: a new therapeutic approach in intractable Tourette syndrome. A report of three cases. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:1094-1100.

21 Vandewalle V, van der Linden C, Groenewegen HJ, et al. Stereotactic treatment of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome by high frequency stimulation of thalamus. Lancet. 1999;353:724.

22 Maddux BN, Riley DE, Whitney CM, et al. Clinical efficacy and video analysis of deep brain stimulation for medically intractable Tourette syndrome [abstract]. Move Disord. 2004;19:1123.

23 Maciunas RJ, Maddux BN, Riley DE, et al. A prospective randomized double-blind trial of bilateral thalamic deep brain stimulation in adults with Tourette syndrome. J Neurosurg. 2007;107:1004-1014.

24 Leckman JF, Riddle MA, Hardin MT, et al. The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale: initial testing of a clinician-rated scale of tic severity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989;28:566-573.

25 Goetz CG, Kompoliti K. Rating scales and quantitative assessment of tics. In: Cohen DJ, Goetz CG, Jankovic J, editors. Tourette Syndrome. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001.

26 Goetz CG, Tanner CM, Wilson RS, et al. A rating scale for Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: description, reliability, and validity data. Neurology. 1987;37:1542-1544.

27 Goetz CG, Pappert EJ, Raman R, et al. Advantages of a modified version of an objective video-based rating scale for Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Mov Disord. 1999;14:502-506.

28 Maddux BN, Riley DE, Whitney CM, et al. Double-blind trial of thalamic DBS for Tourette syndrome: one year follow-up [abstract]. Neurology. 2007;68(suppl):P04.038.

29 van der Linden C, Colle H, Vandewalle V, et al. Successful treatment of tics with bilateral internal pallidum (GPi) stimulation in a 27-year-old male patient with Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome (GTS) [abstract]. Mov Disord. 2002;17(suppl 5):S341.

30 Houeto JL, Karachi C, Mallet L, et al. Tourette’s syndrome and deep brain stimulation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:992-995.

31 Ackermans L, Temel Y, Cath D, et al. Deep brain stimulation in Tourette’s syndrome: two targets? Move Disord. 2006;21:709-713.

32 Servello D, Porta M, Sassi M, et al. Deep brain stimulation in 18 patients with severe Gilles de la Tourette syndrome refractory to treatment: the surgery and stimulation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:136-142.

33 Shields DC, Cheng ML, Flaherty AW, et al. Microelectrode-guided deep brain stimulation for Tourette syndrome: within-subject comparison of different stimulation sites. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2008;86:87-91.

34 Diederich NJ, Kalteis K, Stamenkovic M, et al. Efficient internal pallidal stimulation in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: a case report. Mov Disord. 2005;20:1496-1520.

35 Shahed J, Poysky J, Kenney C, et al. GPi deep brain stimulation for Tourette syndrome improves tics and psychiatric comorbidities. Neurology. 2007;68:159-160.

36 Flaherty AW, Williams ZM, Amirnovin R, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the anterior internal capsule for the treatment of Tourette syndrome: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:403-407.

37 Nuttin B, Cosyns P, Demeulemeester H, et al. Electrical stimulation in anterior limbs of internal capsules in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Lancet. 1999;354:1526.

38 Ackermans L, Temel Y, Bauer NJC, et al. Vertical gaze palsy after thalamic stimulation for Tourette syndrome: case report. Neurosurgery. 2007;61(5):E1100.

39 Mink JW, Walkup J, Frey KA, et al. Patient selection and assessment recommendations for deep brain stimulation in Tourette syndrome. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1831-1838.

40 Okun MS, Fernandez HH, Foote KD, et al. Avoiding deep brain stimulation failures in Tourette Syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:111-112.

41 Gilbert DL. Deep brain stimulation for a teen with tics? Neurology. 2007;68:85.