CHAPTER 117 Surgery for Sacroiliac Joint Syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Surgical treatment for sacroiliac pain can be considered when other therapeutic options have failed, and when the patient’s symptoms or functional limitations are of sufficient magnitude to balance the attendant risks. In the course of a general pain or spine practice a relatively small number of patients will be encountered who fall into this group. For patients with recalcitrant symptoms, it is the practitioner’s responsibility to educate patients about all potentially effective treatments, including those that lie outside the scope of a particular physician’s practice. Although not widely appreciated by most practitioners, extensive literature exists that reports satisfactory results from surgical treatment of sacroiliac pain in appropriately selected patients. This chapter will provide a review of the relevant literature and will describe the approaches to surgical treatment of patients with pain of sacroiliac origin.

PATIENT SELECTION

As is true for most therapeutic interventions, the most important factor in the ultimate success of surgical treatment of sacroiliac pain is proper patient selection. A patient for whom surgical treatment is a consideration should undergo a thorough evaluation that clearly identifies the sacroiliac joint as a pain generator. As coexistent spinal pathology is not uncommon,1 the preoperative evaluation must include a detailed search for other pain generators that may mimic or overlap symptoms arising from the sacroiliac joint. Plain films and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies of the lumbar spine should be obtained, and additional studies such as provocative discography, selective root blocks, median branch blocks, and other studies described elsewhere in this text should be utilized when appropriate. Physical examination maneuvers alone have been demonstrated to be inadequate in the diagnosis of a sacroiliac origin of pain.2,3 Radionuclide imaging is also of limited usefulness in confirming a diagnosis of sacroiliac-mediated pain, due to its very low sensitivity.4 Diagnosis of pain of sacroiliac origin requires an unequivocally positive result from a flouroscopically or computed tomography (CT)-directed injection of local anesthetic into the synovial portion of the sacroiliac joint. False-positive results can be minimized by the use of a double block as described by Maigne et al.5 The author believes that the criteria of Maigne et al. should be modified slightly in that these authors recommended that the patient should report at least 75% reduction of pain for an injection to be considered positive. While percentage reduction of pain is by its nature a very subjective ‘measurement,’ in the author’s experience the response that best predicts a positive outcome from surgical treatment is a response of ‘near complete’ or ‘greater than 90%’ relief of pain. Coexistent pathology can also make any attempt at quantification of pain relief by an intervention that removes only a component of the patient’s symptoms very difficult to interpret, as some patients are more able than others to discriminate different components of their pain complaints. Ultimately, clinical judgment plays a crucial role in the assignment of all diagnoses relating to pain generators in any particular patient. The practitioner should, however, avail himself or herself of all diagnostic information necessary to formulate the best conclusions regarding the sources of pain generation before making a recommendation for surgical treatment of any type.

Only patients who have failed to improve after undergoing a thorough trial of conservative treatment should be considered candidates for surgical treatment. No consensus exists, however, on what constitutes a thorough trial of conservative treatment. Mooney has described a defined course of physical therapy with demonstrated effectiveness in many patients.6 Prolotherapy has advocates, as does repeated corticosteroid injections. The practitioner should be acquainted with the various alternatives for nonsurgical treatment, and be satisfied that nonsurgical measures have been exhausted before making a recommendation for surgical treatment.

SURGICAL ALTERNATIVES

Posterior arthrodesis

Historical review

Goldthwait and Osgood7 reported on the association of low back pain and sacroiliac laxity in pregnant women. They drew attention to the fact that the sacroiliac joints demonstrate motion in nonpathologic conditions and hypothesized that ligamentous laxity associated with pregnancy might lead to hypermobility and associated pain. Albee8 reported on his dissections of 50 pelvic specimens and drew attention to the fact that the sacroiliac joints were synovial joints and not ‘synchondroses’ as many physicians of that period assumed. Baer9 reinforced the fact that the sacroiliac joints were synovial joints and recommended manipulation under anesthesia as treatment for chronic sacroiliac pain. Gaenslen reported on his surgical treatment first in 1921,10 and later reported on 9 patients’ outcomes at varying intervals after surgery.11 Gaenslen’s operation consisted of a posterior approach to the joint by splitting the ilium to reflect a bone flap with the gluteal musculature attached. A window through the remaining cancellous portion of the ilium was then made to expose the synovial portion of the joint. Curettage of the interior of the joint was carried out. He reported good or very good results in 7 of 9 patients (78%). Smith-Petersen and Rogers12 reported on 26 patients who had undergone sacroiliac arthrodesis for chronic sacroiliac pain (one of whom was Smith-Petersen’s wife). Smith-Petersen’s technique differed slightly from Gaenslen’s technique in that the gluteal musculature was reflected and a transiliac window was made to gain access to the synovial portion of the joint. Decortication of the interior of the joint was carried out with curettes and gouges, and the window was replaced and countersunk across the joint after removal of the cartilage and subchondral bone from the window fragment, allowing opposition of cancellous surfaces between the sacrum and ilium. He reported clinical success in 23 of 26 patients (89%), with radiographic union in 95%. Twenty-five of 26 patients (96%) returned to their prior occupation. Willis Campbell13 reported an extra-articular method of fusion, in which the posterior ilium and adjacent sacrum were exposed and decorticated, and bone graft was placed into the gutter dorsal to the joint proper. He reported that five of seven patients had a successful outcome, with two patients being too close to surgery to assess the outcome at the time of his publication.

After this series of publications describing differing techniques, all with successful outcomes, there was a surprising absence of publications on both the diagnosis and the surgical treatment of sacroiliac pain. The most likely reason for this was the popularization of the diagnosis of disc pathology and its association with sciatica. Although Mixter and Barr14 are frequently given credit for ‘discovering’ the herniated lumbar disc, several publications discussing both the pathology15,16,17,18 and surgical treatment19 pre-date the Mixter and Barr article. Nonetheless, the influence of the Mixter and Barr article was apparently of sufficient magnitude to largely eliminate the sacroiliac joint from attention of authors in neurosurgical and orthopedic journals. In the 40 years following the Mixter and Barr article, only a handful of publications in the surgical literature make mention of the sacroiliac joint as being a source of low back pain and sciatica, with the exception of papers reporting on septic arthritis and sacroiliitis arising from rheumatoid disorders. Extending the work of Steindler and Luck,20 Haldeman and Soto-Hall21 recommended diagnosis of sacroiliac pain by injection of procaine, although their injection technique involved injecting large volumes (20–30 cc) of 1% procaine into the ligamentous portion of the joint. No mention of surgical treatment was made in their article. Norman and May22 brought attention to the fact that sacroiliac pain could mimic symptoms arising from intervertebral disc lesions, a fact largely unrecognized until the refinement of spinal diagnostic techniques in the 1990s.23

Orthopedic and neurosurgical journals remained silent on the issue of surgical treatment of sacroiliac pain until 1987, when Waisbrod and colleagues reported on 21 patients who underwent posterior uninstrumented sacroiliac arthrodesis for chronic sacroiliac pain.24 Diagnostic evaluation of this cohort included a provocative test, radiographic evaluation with plain films and CT images of the sacroiliac joint, radionuclide imaging, and several psychological questionnaires. The psychological screening was not utilized in the early part of the study period (1981–84). The provocative test consisted of injection of 10% NaCl solution into the ‘dorsocaudal’ portion of the joint. To be considered a positive test, this intervention was required to exactly reproduce the patient’s typical pain pattern. One to 2 cc of local anesthetic was also injected, and presumably this alleviated the previously aggravated symptoms, although the authors were not specific on this point. Follow-up ranged between 12 and 55 months. To be considered for surgery, the patients had to have positive findings on radiographic, nuclear medicine, and provocative testing. Patients with psychological disturbances were excluded regardless of other findings in the later part of the study (1984–86). Patients were divided into satisfactory and unsatisfactory outcomes. A satisfactory outcome required reduction of symptoms of at least 50%, no need for analgesics, and resumption of their preoperative occupation. They reported 50% satisfactory results overall, although this included six patients who would not have been operated upon in the later portion of the study based on psychological exclusion criteria. When they excluded the six patients with psychological disturbances, they concluded that a satisfactory result could be expected in 70% of cases. Moore reported on 13 patients treated with instrumented posterior sacroiliac arthrodesis for chronic sacroiliac pain at the 1992 North American Spine Society meeting.25 Patients were offered surgical treatment when conservative treatment had failed and the patients had unequivocal relief of their typical symptoms after injection of local anesthetic into the synovial portion of the joint under CT or fluoroscopic guidance. Six of the patients had prior failed lumbar spine surgery. He reported 10 excellent, one fair, and two poor results. This same group of patients was followed up again, with successively larger groups in 1995, 1997, and 1998.1,26,27 In the 1998 review, Moore reported on 59 patients who had isolated sacroiliac joint pain and no coexistent spinal pathology or prior spinal surgery.27 Chart reviews and phone interviews were carried out, and outcome variables included subjective pain relief, satisfaction with outcome, surgical complications, and incidence of pseudoarthrosis. All phone interviews were carried out by an independent research assistant (i.e. the surgeon did not carry out any of the interviews). Of these patients, 53 (89.8%) had a satisfactory outcome, and six (10.2%) were considered failures. Of the six patients who were failures, four had a pseudoarthrosis. The other two patients were clinical failures despite evidence of solid arthrodesis on fine-cut CT scanning. Complications were limited to one superficial wound infection, one intraoperative fracture into the sciatic notch during creation of the transiliac window, necessitating intraoperative repair which healed without incident. One patient required reoperation to retrieve a screw that penetrated the anterior cortex of the sacrum, causing mild radicular dysesthesia. Except for this latter case, there was no incidence of neurologic complications and there were no cases of visceral or vascular injury.

Keating et al.29 reported on follow-up of 28 patients who underwent posterior arthrodesis of the sacroiliac joint for chronic sacroiliac pain. Statistically significant improvement between preoperative and postoperative pain was observed and patients remained improved up to the minimum 1 year follow-up period. Berthelot et al.30 reported on posterior sacroiliac arthrodesis in the treatment of two patients with recalcitrant sacroiliitis related to spondyloarthropathy. Both patients were significantly improved at follow-up of greater than 2 years. Belanger and Dall31 reported four patients who underwent posterior instrumented sacroiliac arthrodesis over a 10-year period, all with ultimately satisfactory results. There was one reoperation to remove internal fixation, and no significant complications were reported.

Instrumentation without fusion

Lippitt reported on the use of percutaneous screw stabilization of the sacroiliac joint without any attempt to obtain bony fusion.32 In reviewing 43 patients, he reported that 23 patients (53%) had significant or complete relief of symptoms and seven patients (6%) had no improvement at all, with the remaining 13 patient showing varying degrees of partial pain relief. Complications of nerve injuries and RSD were reported, although surprisingly no cases of screw breakage or displacement occurred. The concept of stabilization without arthrodesis has not met with much acceptance at this point and should be considered investigational.

Anterior sacroiliac arthrodesis

Although the anterior approach to the sacroiliac joint is one which is familiar to most orthopedic surgeons from their training in the treatment of pelvic ring fractures, it has been associated with significant complications when used in the setting of elective sacroiliac instrumentation and fusion.33 The L5 nerve root is at risk as it crosses the anterior portion of the joint and can be injured during the dissection required to gain access to the interior of the joint and to place internal fixation.34 In addition, it is difficult by this technique to reach the synovial portion of the joint. Achieving compression across the joint by anterior plating alone is problematic as well. The anterior approach may have utility in salvage or revision surgeries, but should be viewed with caution in the primary surgical treatment of sacroiliac pain

Author’s preferred technique: posterior instrumented arthrodesis

The surgical technique is a modification of that described by Smith-Petersen and Rogers.12 The patient is placed under general anesthesia and a Foley catheter is inserted into the bladder. An image table is used and the patient is placed in a prone position on chest rolls. An image intensifier is used to visualize the joint prior to marking the skin incision. In the anteroposterior projection in this position, the posterior superior iliac spine will usually overlay the midportion of the sacroiliac joint and a curvilinear skin incision is marked centered on this point. The length depends upon the size of the patient, but usually is usually 8–11 cm in length.

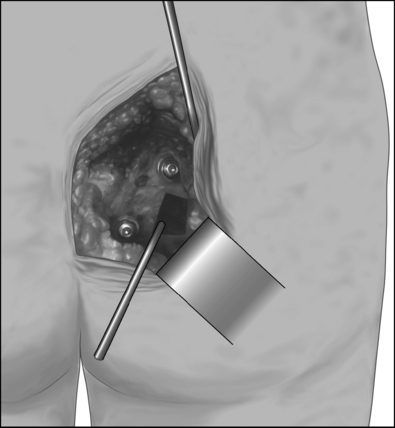

Preparation is then made for creating a transiliac window into the synovial portion of the joint. It is desirable to create as large a window as possible without sacrificing the interosseous ligaments. The boundaries for the window and the thickness of the overlying ilium can be measured on the preoperative CT scan, which should be obtained in every case. The anterior extent of the window can be measured relative to the posterior superior iliac spine. While individual anatomy varies, the preoperative CT scan will show this to be approximately 5–6 cm anterior to the posterior superior iliac spine. A Midas Rex K-1 dissecting tool is used to score the outer cortex of the ilium. Figure 117.1 shows the approximate location of the window relative to the previously placed screws. The window is completed using straight and curved osteotomes. The thickness of the ilium at this level is greater than most surgeons realize, and for this reason it is important to measure this on the preoperative CT scan. It is helpful to have osteotomes that have centimeter markers on their shafts. A common pitfall is to fail to reach the joint because of not creating a deep enough window. Out of concern for the anterior pelvic structures (iliac artery and vein, lumbosacral plexus, rectum), a surgeon may be reluctant to watch 3–4 cm of osteotome enter the ilium. Many so called ‘failed’ sacroiliac fusions occur because the surgeon never finds the true interior of the joint, and stops short of the joint in making the window, visualizing only subchondral bone on the iliac side of the joint. By following the rectangular outline of the window, the straight and curved osteotomes can be used to fenestrate the subchondral bone and cartilage on the iliac side of the joint, and the window can be removed en bloc, which will allow clear identification of the hyaline cartilage on the sacral side of the joint in the depth of the window. (Helpful hint: when the osteotome reaches the subchondral bone on the iliac side of the joint, a characteristic change of pitch can be heard as the mallet impacts the osteotome, and this is a useful clue in orienting the surgeon as to the correct depth to place the instrument.) If concern exists about the depth to which the osteotome has penetrated, the image intensifier may be used in multiple projections to identify the position of the end of the osteotome relative to the joint surfaces.

Once the window is created and the sacral side of the joint clearly visualized, decortication of the sacral side of the joint can be carried out using osteotomes and curettes. Angled curettes are useful in expanding the interior dimensions of the window and in removing remaining subchondral bone and cartilage from the synovial portion of the joint. All bone removed is saved and cleaned of cartilage and soft tissue, to be reused as bone graft. Additional bone graft is harvested by osteotomizing the posterior superior iliac spine and using gouges and curettes to retrieve cancellous bone from this area. The cancellous bone is morselized and packed into the lateral margins between the ilium and sacrum in the depth of the window. Subchondral bone and cartilage is removed from the iliac fragment removed in creating the window, and this is countersunk across the joint. A secure interference fit can be achieved by packing additional bone along the margins of the window. Multiple perforations in the facing cortex may then be made with the Midas Rex K-1 dissecting tool to facilitate incorporation.

Postoperative care

The patient is optimally mobilized on the day of surgery and is kept non-weight bearing on the operated side for 8 weeks. The drain is removed at 24–48 hours. The patient can usually be discharged on the second postoperative day, after demonstrating competence in utilization of crutches and maintaining a non-weight bearing status on the operated side. Patients frequently experience dramatic relief of their preoperative pain in the early (24–48 hours) time period and have to be cautioned against early resumption of weight bearing. At 2 months after surgery crutches are discontinued. Patients are then referred to physical therapy for gluteal strengthening and gait normalization. Patients will tend to have a limp because of gluteal weakness from 2 months of non-weight bearing, and will tend to walk with the hip on the operated side in external rotation. Four to six weeks of physical therapy is usually sufficient to normalize gait and eliminate the limp. Figure 117.1 shows diagrammatically the appearance of the procedure prior to wound closure. Figure 117.2 shows a typical postoperative X-ray.

Complications

Potential complications of the techniques described above include infection, vascular injury either to the superior gluteal artery or nerve during the approach, visceral, vascular or neurologic injury due to overpenetration of a drill bit, screws, or osteotomes, pseudoarthrosis, as well as systemic complications associated with any operation utilizing general anesthesia, such as deep venous thrombosis, atelectasis, and urinary tract infection. Reported complications, however, have been rare. No cases of vascular, visceral, or permanent neurologic complications have been reported. The most common complication reported has been pseudoarthrosis,26 which occurred in 7 of 77 patients (7/77=9%). Pseudoarthrosis was diagnosed by fine-cut CT scanning. All pseudoarthrosis occurred in smokers. Five patients underwent reoperation in an attempt to repair the pseudoarthrosis. Three patients went on to a solid arthrodesis after the second surgery and had a good result. The other two patients did not heal after a second surgery and continued to have unsatisfactory results. Experience with the technique and requiring that patients quit smoking prior to surgery will minimize the incidence of pseudoarthrosis.

Illustrative cases

Case 1

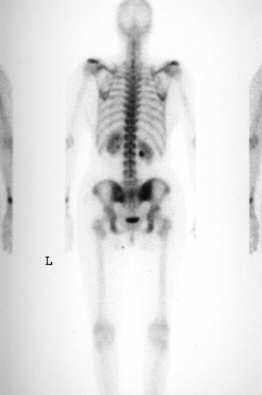

The patient was an athletic 35-year-old female with a complaint of right buttock pain with radiation to the posterior thigh. Symptoms had been present for 6 months and were becoming increasingly severe. Physical therapy had been prescribed and had not improved her symptoms. There was no history of trauma, spondyloarthropathy, or other rheumatologic disorder. Plain films of the thoracic and lumbar spine revealed a mild idiopathic scoliosis and were otherwise unremarkable. An MRI of the lumbar spine demonstrated no disc or neurocompressive pathology (Fig. 117.3). A bone scan showed mild increased uptake in the right sacroiliac joint (Fig. 117.4). The patient described pain when rolling over in bed. She denied using a nonreciprocal gait when ascending stairs. Physical examination showed normal motor strength in the lower extremities as well as normal sensation and symmetric deep tendon reflexes. Waddel’s signs were negative. The Faber maneuver was negative bilaterally. A CBC was normal. ESR = 7 mm/hr and CRP was within normal limits.

Fig. 117.3 MRI of a 35-year-old female with right-sided sciatica. Normal disc and canal anatomy is seen.

The patient underwent a fluoroscopically guided injection of Celestone, 0.5% marcaine, and 1.0% lidocaine into the right sacroiliac joint. The patient’s pain was nearly completely eliminated for approximately 8 hours, at which time it returned and was once again severe. She continued to be unable to pursue normal or recreational activities. She elected to undergo a posterior sacroiliac arthrodesis (Fig. 117.5). Surgery was uncomplicated and she was discharged from the hospital 48 hours after surgery on crutches, non-weight bearing on the right side. The patient was seen at 1 month following surgery and reported complete resolution of her preoperative pain. At 2 months, crutches were discontinued and physical therapy for gluteal strengthening and gait normalization was initiated and continued for 4 weeks. At 6 months post surgery, the patient was seen and reported only 10% pain. At follow-up at 34 months she reported 0% pain, was working in her usual occupation as a cosmetologist without restrictions, and was able to participate in unrestricted recreational activity.

Case 2

The patient was a 36-year-old mother of 4 children with a long history of low back pain that had gotten worse with each of her pregnancies. Her youngest child was 3 years old, and since the time of that delivery her symptoms had become progressively worse. She rated her typical pain as 80–90% in severity, and was using morphine sulfate for pain control. She had many evaluations of the lumbar spine without a clear diagnosis being obtained, and had undergone several courses of physical therapy with no improvement. An MRI of the lumbar spine showed minor degeneration at L4–5 (Fig. 117.6). Provocative discography was carried out and was negative for reproduction of concordant pain (Fig. 117.7). Plain films and CT showed oseitis condensans ilii affecting both sacroiliac joints, right greater than left (Fig. 117.8). A flouroscopically guided injection of local anesthetic into the right sacroiliac joint afforded nearly complete relief of her right-sided pain. The patient underwent a posterior instrumented sacroiliac arthrodesis on the right side (Fig. 117.9) At 2 months crutches were discontinued. Physical therapy normalized her gait, and the patient reported complete relief of her right-sided symptoms. She continued, however, to have pain over the left sacroiliac joint. A flouroscopically guided injection of the left sacroiliac joint afforded complete relief of her residual pain. Six months after her index procedure, she underwent a left-sided sacroiliac fusion without complication (Fig. 117.10). At 2-year follow-up from her index procedure, the patient reported 10% pain, was using no pain medication, and had resumed unrestricted activity.

Neuroaugmentation

Cavillo et al. reported on two patients believed to have bilateral sacroiliac pain after lumbosacral arthrodesis.35 They were treated by bilateral implantation of stimulating electrodes into the third sacral foramina, to treat sacroiliac pain. One patient developed an infection and the electrodes had to be removed. In the other patient, there was subjective reduction of pain of 56%, although the patient was still using narcotic medication at follow-up. As of the time of this writing, there have been no other published reports on this mode of treatment.

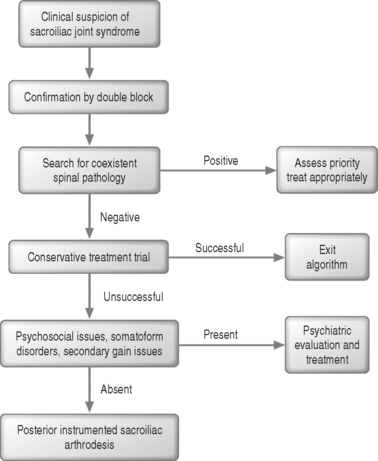

CONCLUSIONS

Surgical treatment of sacroiliac pain should be considered an option for appropriately selected patients who have failed conservative treatment and who have disabling symptoms. Figure 117.11 shows a flowchart for evaluation of a patient for surgical treatment of sacroiliac pain. The literature supports posterior sacroiliac arthrodesis over other surgical options at this time, although controlled studies are required to further identify the optimum surgical treatment. The best results can be expected in nonsmoking patients with pain of sacroiliac origin and no coexistent spinal pathology.

1 Moore MR. Diagnosis and surgical treatment of chronic painful sacroiliac joint dysfunction. In: Vleeming A, Mooney V, Dorman T, et al, editors. The integrated function of the lumbar spine and sacroiliac joint. Rotterdam: ECO; 1995:341-354.

2 Dreyfuss P, Michaelsen M, Pauza K, et al. The value of medical history and physical examination in diagnosing sacroiliac joint pain. Spine. 1996;21:2594-2602.

3 Slipman CW, Sterenfeld EB, Chou LH, et al. The predictive value of provocative sacroiliac joint stress maneuvers in the diagnosis of sacroiliac joint syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1998;79:288-292.

4 Slipman CW, Sterenfeld EB, Chou LH, et al. The value of radionuclide imaging in the diagnosis of sacroiliac joint syndrome. Spine. 1996;21:2251-2254.

5 Maigne JY, Aivalliklis A, Pfefer F. Results of sacroiliac joint double block and value of sacroiliac pain provocation tests in 54 patients with low back pain. Spine. 1996;21:1889-1892.

6 Mooney V. Evaluation and treatment of sacroiliac dysfunction. In: Vleeming A, Mooney V, Dorman T, et al, editors. The integrated function of the lumbar spine and sacroiliac joint. Rotterdam: ECO; 1995:393-407.

7 Goldthwait JE, Osgood RB. A consideration of the pelvic articulations from an anatomical, pathological and clinical standpoint. Boston Med Surg J. 1905;152:593-601.

8 Albee FH. A study of the anatomy and the clinical importance of the sacroiliac joint. JAMA. 1909;53:1273-1276.

9 Baer WS. Sacro-iliac strain. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1917;28:159-163.

10 Gaenslen FJ. Wisconsin Med J. 1921;20:20.

11 Gaenslen FJ. Sacro-iliac arthrosesis. Indications, author’s technique and end results. JAMA. 1927;89:2031-2035.

12 Smith-Petersen MN, Rogers WA. End-result study of arthrodesis of the sacroiliac joint for arthritis – traumatic and non-traumatic. J Bone Joint Surg. 1926;8:118-136.

13 Campbell WC. An operation for extra-articular fusion of the sacroiliac joint. Surg Gynecol Obstetr. 1927;45:218-219.

14 Mixter W, Barr J. Rupture of the intervertebral disc with involvement of the spinal canal. N Engl J Med. 1934;211:210-215.

15 Virchow RLK. Untersuchung uber die Entwickelung des Schadelgrund. Berlin: Reimer, 1857.

16 von Luschka H. Die Hallogelenke des menschlichen Korpens. Berlin: Riemer, 1858.

17 Goldthwait JE. The lumbosacral articulation: an explanation of many cases of ‘lumbago,’ ‘sciatica,’ and paraplegia. Boston Med Surg J. 1911;164:365-372.

18 Middleton GS, Teacher JH. Injury of the spinal cord due to rupture of an intervertebral disc during muscular effort. Glasgow Med J. 1911;76:1-6.

19 Dandy WE. Loose cartilage from intervertebral disc simulating tumor of the spinal cord. Arch Surg. 1929;19:660-672.

20 Steindler A, Luck JV. Differential diagnosis of pain low in the back. Allocation of the source of pain by the procaine hydrochloride method. JAMA. 1938;110:106-113.

21 Haldeman KO, Soto-Hall R. The diagnosis and treatment of sacroiliac conditions by the injection of procaine. J Bone Joint Surg. 1938;20:675-685.

22 Norman GF, May A. Sacroiliac conditions simulating intervertebral disc syndrome. West J Surg Gynecol Obstetr. 1956;64:461-462.

23 Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Bogduk N. The sacroiliac joint in chronic low back pain. Spine. 1995;20:31-37.

24 Waisbrod H, Krainick JU, Gerbershagen HU. Sacroiliac joint arthrodesis for chronic lower back pain. Arch Orthopaed Trauma Surg. 1987;106:238-240.

25 Moore MR. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic sacroiliac arthropathy. Orthopaed Trans. 1994;18(1):255.

26 Moore MR. Surgical treatment of chronic painful sacroiliac joint dysfunction. In: Vleeming A, Mooney V, Dorman T, et al, editors. Movement, stability, and low back pain. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1997:563-572.

27 Moore MR. Outcomes of surgical treatment of chronic painful sacroiliac joint dysfunction. In: Vleeming A, Mooney V, Tilscher H, et al, editors. 3rd Interdisciplinary World Congress on Low Back and Pelvic Pain, November 19–21, 1998, Vienna, Austria. Rotterdam: ECO; 1998:218-226.

28 Moore MR. Surgical treatment of chronic painful sacroiliac joint arthropathy. Poster presentation, 13th annual meeting of the North American Spine Society, San Fransisco, October 28–31, 1998.

29 Keating JG, Avillar MD, Price M. Sacroiliac joint arthrodesis in selected patients with low back pain. In: Vleeming A, Mooney V, Dorman T, et al, editors. Movement, stability, and low back pain. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1997:573-586.

30 Berthelot JM, Gouin F, Glenmarec J, et al. Possible use of arthrodesis for intractable sacroiliitis in spondyloarthropathy. Spine. 2001;26:2297-2299.

31 Belanger TA, Dall BE. Sacroiliac arthrodesis using a posterior midline fascial splitting approach and pedicle screw instrumentation: A new technique. J Spinal Disord. 2001;14:118-124.

32 Lippitt AB. Percutaneous fixation of the sacroiliac joint. In: Vleeming A, Mooney V, Dorman T, et al, editors. The integrated function of the lumbar spine and sacroiliac joint. Rotterdam: ECO; 1995:371-390.

33 Kim DH, Patel AJ, Brown CW, et al. Arthrodesis of the sacroiliac joint syndrome. Preliminary review of results. Presented at the Annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, February 22, 1996.

34 Moed BR, Kellan JF, Mclaren A, et al. Internal fixation for the injured pelvic ring. In: Tile M, Helfet DL, Kellan JF, editors. Fractures of the pelvis and acetabulum. 3rd edn. New York: Williams and Wilkins; 2003:249-250.

35 Calvillo O, Esses SI, Ponder C, et al. Neuroaugmentation in the management of sacroiliac joint pain: report of two cases. Spine. 1998;23(9):1069-1072.