CHAPTER 108 Neuraxial Drug Administration to Treat Pain of Spinal Origin

INTRODUCTION

Advances in neurobiology serve as the basis for current and evolving implantable pain modalities, consisting of neurostimulation and neuraxial drug administration systems.

Both neurostimulation and intrathecal drug administration systems are reversible and nondestructive neuromodulatory techniques that can reduce pain of spinal origin. Neurostimulation is preferred over neuraxial drug delivery when the patient’s problem is amenable to both techniques because drug delivery systems require regular medication refills. Neuraxial medication delivery is indicated when side effects of systemic analgesics limit the ability to deliver effective doses of medications. Prager and Jacobs provide a comprehensive review of patient selection for these neuromodulatory techniques.1

RATIONALE

The discovery of opioid receptors2,3 provided a rational basis for the delivery of opioid drugs intraspinally. By 1979, reports of epidural4 and intrathecal5 opioid delivery in humans had entered the peer-reviewed literature.

Intraspinal infusions delivered drugs directly to opioid receptors, limited systemic exposure, and by decreasing the opioid dosage required for pain relief, generally reduced side effects, which facilitated the provision of greater analgesia. The benefits of short-term spinal analgesia, primarily for patients with intractable cancer pain, led to investigation of longer-term continuous subarachnoid opioid infusions for the management of both cancer pain6–17 and noncancer pain, such as that produced by failed back surgery syndrome.18–30 Pain specialists currently are successfully using opioids to treat patients with chronic noncancer pain, noting that such patients can benefit from sustained analgesia and better function without becoming addicted.31

The key to appropriate treatment of pain is proper diagnosis. Pain can be characterized as nociceptive (e.g., somatic pain), neuropathic (pain from nerve injury), or idiopathic. Pure nociceptive pain usually responds well to systemic opioids. Neuropathic pain responds to opioids at higher doses and often is responsive to a large number of antineuropathic medications (Table 108.1). Failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS) pain usually is a mixed type of pain that is both nociceptive and neuropathic.

Table 108.1 Updated pain treatment interventions and medications32,36

| Exercise |

| Meditation, relaxation, yoga, traditional biofeedback and neurobiofeedback |

| Over-the-counter medications (aspirin, traditional nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs) and cyclooxygenase inhibitors |

| Antineuropathic adjunctive medications (tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, GABAergic drugs, other antispasmodics, anticonvulsants, local anesthetics, calcium-channel blockers, substance P-depleting amines, α2 agonists, NMDA receptor antagonists, tramadol) and other adjunctive medications: corticosteroids |

| Physical rehabilitation: physical therapy, work hardening, occupational therapy, Pilates |

| Somatic and sympathetic nerve blocks |

| Cognitive and behavioral therapies |

| Opioid medications combined with adjuvants |

| Pure high-potency, time-released opioid medications with breakthrough short-acting opioid medications |

| Spinal cord stimulation if pain is segmental |

| Intraspinal infusion analgesia |

| Neurodestructive procedures |

In appropriately selected patients, intraspinal therapy has been refined through accumulated experience from treating tens of thousands of cases (more than 25 000 with implantable pumps32), improved drug delivery systems, and new pharmacologic approaches, making it an effective technique for the control of intractable pain.

INTRASPINAL DRUG DELIVERY SYSTEMS

Intraspinal drug delivery can be accomplished by a variety of means including percutaneous catheter, percutaneous catheter with subcutaneous tunneling, implanted catheter with subcutaneous injection site, totally implanted catheter with implanted reservoir and manual pump, and totally implanted catheter with implanted infusion pump.33 The choice of the system depends on the indication for intraspinal therapy, the need for bolus versus continuous infusion, the patient’s general medical condition, available support services, ambulatory status, life expectancy, and cost. In general, percutaneous tunneled catheters, external pumps, and implanted passive reservoirs can be more cost-effective when life expectancy is a matter of weeks to months. A fully implanted pump becomes economical if life expectancy is longer than 3 months.34

The first ‘permanent’ catheter for intraspinal drug delivery was developed by DuPen et al.35 in the 1980s. They adapted Broviac catheter technology to create an exteriorized, permanent, three-piece, silicone epidural catheter. The catheter was implanted in 55 cancer patients who had metastatic disease and intractable pain. After 3891 days of catheter use, there were no catheter infections and 18 minor side effects. The rate of hospitalization for pain control was decreased by 90% in these patients. In one series of 350 reported implantations of the DuPen catheter, there were 30 superficial catheter infections, 8 deep catheter infections, and 15 epidural or intrathecal catheter infections, representing a 15.1% infection rate. The DuPen catheter continues to be marketed for use with an external pump. It may represent a cost-effective alternative for patients with a short life expectancy, such as patients with severe metastatic disease to the spine. However, the DuPen catheter and similar external systems have limited applicability in treating noncancer pain of spinal origin.

Two types of implantable drug delivery systems are marketed currently in the United States.34,36 The first commercially available implantable pump delivered medication at a fixed rate and consisted of two chambers separated by a flexible bellows in addition to a side port for bolus injections.3 Outflow was regulated by compressed Freon gas, so changes in altitude and temperature affected drug flow. Because the pump ran at a fixed rate, changes in the rate of medication delivery could be accomplished only by emptying the pump and refilling it with a different concentration of medication. This pump was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for epidural administration of preservative-free morphine. The original pump has been superseded by a new model,2 which has a single raised septum and no side port. Although essentially the same, the new pump was modified by removing the side port to minimize the potential for overdose. A special needle with a needle shaft aperture and a closed needle tip is used to deliver fluid directly into the catheter rather than the drug reservoir.33 A second and third fixed-rate pump are now available.

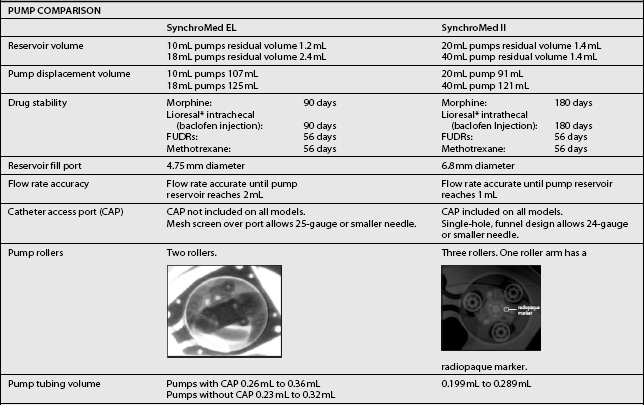

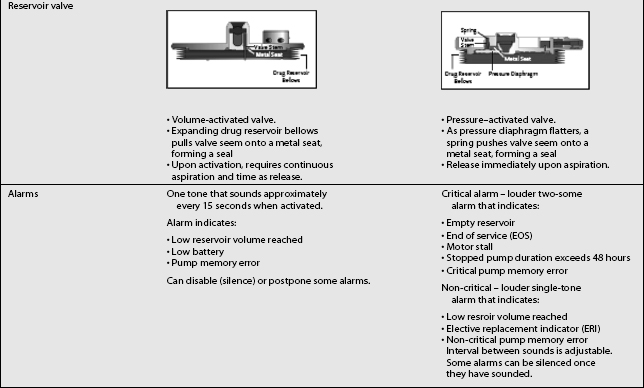

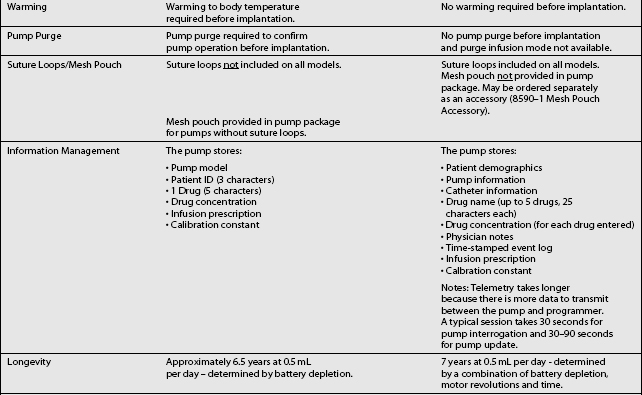

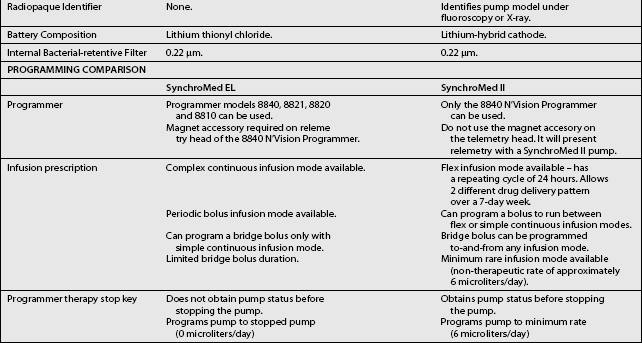

The third type of implantable delivery system is a programmable electronic pump powered by batteries, which last up to 7 years depending on flow rate.4 Two pumps are FDA approved and contain either 10 or 18 mL collapsible reservoirs, a volume activated valve and a pump or 20 or 40 mL reservoirs, a pressure activated valve and a pump, both of which push medication through a bacteriostatic filter and catheter. Comparison of these pumps is found in Table 108.2.

These pumps are FDA approved for epidural or intrathecal infusion of preservative-free morphine sulfate for chronic, intractable pain, and baclofen for chronic spasticity. Ziconotide was FDA approved for intrathecal use for pain in these pumps in 2004. Both pumps are programmed, using noninvasive telemetry to control medication concentration, volume, and dosage. The programmable feature allows flexible dosing options over time and permits precise dose titration. Both pump types require refilling under sterile conditions at least every several months, depending on flow rate.37

In deciding whether to implant a programmable pump or a fixed-rate pump, several factors should be considered, including their specific attributes. Table 108.3 compares the attributes of the two pump types. The programmable pumps provide greater flexibility of medication delivery and are more adjustable. However, a programmable pump is more expensive and needs to be replaced when the battery fails.

| Consideration | Programmable pump | Fixed-rate pump |

|---|---|---|

| Cost |

* Hardware cost is one component of overall implantation costs. Other costs include operating suite, recovery room, radiology facility and professional fees, anesthesiology professional fees, surgical professional fees, and medications. When considering total cost, hardware cost represents only a small amount.

† Battery lifespan is estimated to be up to 7 years. Surgical costs are incurred for replacement.

‡ Only a factor in pump preparation, not at physiological temperatures.

PATIENT SELECTION AND SCREENING TRIALS

The literature is virtually unanimous in emphasizing the importance of appropriate patient selection if intraspinal pain therapy is to be successful.1 Patients with chronic pain are subject to neurophysiologic, emotional, and behavioral influences, which govern their perception of pain and of pain relief. Therefore, treatment of chronic noncancer pain is multidisciplinary, drawing on cognitive and behavioral psychological therapies, functional rehabilitation, orthopedic and neurologic surgery, medications, nerve blockade, neuroaugmentive and sometimes neurodestructive procedures. The pain treatment continuum in Table 108.1 lists these interventions and the antineuropathic medications currently used to treat intractable pain.32

Indications and contraindications for intraspinal opioid therapy appear in Table 108.4.34 Intraspinal drug delivery has been used primarily for patients with nociceptive pain, which has proved to be opioid responsive. Experience in intraspinal treatment of neuropathic pain is more limited, although several studies indicate that neuropathic pain may respond to intraspinal delivery of escalating doses of opioids, or to nonopioid medications.34,38 Finally, a screening trial allows both physician and patient to assess intraspinal drug delivery before committing to pump implantation.

Table 108.4 Updated indications and contraindications for intraspinal drug delivery34,36,39

| INDICATIONS | |

| Chronic pain with known pathophysiology | |

| Sensitivity of pain to medication being used | |

| Failure of more conservative therapy | |

| Favorable psychosocial evaluation | |

| Favorable response to screening trial | |

| CONTRAINDICATIONS | |

| Systemic infection | |

| Coagulopathy | |

| Allergy to medication being used | |

| Inappropriate drug habituation (untreated) | |

| Failure to obtain pain relief in a screening trial | |

| Unusual observed behavior during screening trial | |

| Poor personal hygiene | |

| Poor patient compliance | |

Numerous screening protocols exist. Trials can incorporate epidural or intrathecal administration, bolus injection, a series of injections, or continuous infusion, and they can be conducted on an inpatient or outpatient basis. Pure opioid or a mixture containing opioid can be administered. The duration of the trials varies from 24 hours to longer than 1 week. No protocol can be considered superior or definitive on the basis of current research. However, approximating the conditions of long-term therapy during the trial would seem to offer the best chance for assessing efficacy and tolerance. Table 108.5 compares the advantages of each trial technique.39

Table 108.5 Comparison of neuraxial trial techniques39

The choice of protocol is influenced by the patient’s overall condition, the physician’s preference and experience, the available facilities and resources, the practice environment, and the payer coverage. Medicare reimbursement, for example, requires ‘a preliminary trial of intraspinal opioid drug administration … with a temporary intrathecal/epidural catheter.’40 The question of epidural versus intrathecal administration continues to be debated, although no study has directly compared the two routes of administration. Although the epidural route is more convenient, an epidural dose must be roughly 10 times an intrathecal dose to provide equivalent analgesia.

Two questions are fundamental. Is the patient’s pain responsive to opioid therapy? Can the patient tolerate the planned drug and dosage?36 The physician and patient should agree in advance on the goals of the trial and on the measures to be used for assessment of the outcome. For example, if returning to work is a goal of long-term intraspinal drug therapy, the patient should be evaluated by a rehabilitation specialist during the screening trial. In general, candidates should not proceed to implantation unless their pain can be reduced by at least 50%.9,41 Behavioral observation during the trial adds to the information used for making decisions regarding permanent implantation.42

SURGICAL IMPLANTATION

Device manufacturers provide recommended surgical procedures, which can be adapted to surgeon and institutional preference. The surgical procedure has two steps: placement of the catheter and implantation of the reservoir or pump. Implantation technique varies widely, even for a single type of pump, as Krames and Chapple43 reported in their review of 202 patients in 22 centers.

Most of the catheters were inserted between L2 and L4 (87.2%), introduced through the midline (65.1%), or positioned with their tips at T10 to T12 (64.1%). Also, 95% of the catheters were anchored, 43.8% with a right-angled anchor and 44.8% with a butterfly anchor. Catheter position was confirmed in 94.8% of the cases. Follett et al. analyzed catheter-related complications and determined that paramedian insertion, appropriate anchoring, and placement with redundant loops reduced the chance of complications.44

DRUG SELECTION

Intraspinal drugs must be preservative free. Alcohol, phenol, formaldehyde, and sodium metabisulfite, common drug preservatives, are all toxic to the central nervous system. Any drug packaged in a multidose vial probably contains preservatives and should not be used for intraspinal administration.45 Preservative-free morphine sulfate is the only drug approved by the FDA for intraspinal delivery for pain relief.

Its long history of clinical use, long duration of action (12–24 hours), and relative ease of use explain why it remains the gold standard for intraspinal therapy. If morphine is poorly tolerated, other opioids (hydromorphone, meperidine, methadone, fentanyl, and sufentanil) also can be used intraspinally. Care must be taken to ensure that the medication preparation is compatible with the pump tubing, and that the medication is pure and preservative free. Some meperidine preparations have rendered the SynchroMed pump (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) inoperable by damaging internal tubing (personal communication with Medtronic personnel). The pharmacokinetic properties of various drugs (their lipid solubility, pH, pKa, molecular weight, and opioid receptor affinity) determine time to onset of action, duration of action, uptake and distribution, and side effects. Lipophilic medications such as sufentanil do not spread more than several neurotomes beyond the delivery site at the catheter tip, whereas hydrophilic medications such as morphine circulate throughout the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Furthermore, the site of drug delivery (epidural versus intrathecal) affects distribution. Drugs delivered epidurally must first cross the dura and arachnoid membranes before diffusing to their site of action, whereas drugs delivered intrathecally diffuse passively to the spinal cord. Morphine, which has low lipid solubility and high receptor affinity, diffuses slowly and remains bound for prolonged periods. Unfortunately, the risk of central nervous system side effects (sedation, nausea and vomiting, and respiratory depression) is greater with hydrophilic drugs, such as morphine, than with lipophilic drugs, such as fentanyl or sufentanil. These lipophilic drugs have a rapid onset and prolonged duration of action.32,36,37

Satisfactory results with a morphine–bupivacaine combination have been reported in several studies of cancer and noncancer pain, although high concentrations of epidural morphine were required and side effects included transient paresthesias, motor blockade, and gait disruption.34 The study of van Dongen et al.46 followed a group of cancer patients treated with intrathecal morphine and bupivacaine through a tunneled percutaneous catheter. Of 17 patients treated with this admixture because morphine alone was insufficient to relieve pain, 10 improved significantly and four moderately. The three patients who experienced no improvement also had clinical signs of severe depression. No serious complications were reported. A more recent study by a similar group found that intrathecal morphine and bupivacaine slowed the progression of morphine dose, as compared with morphine given alone. These authors attributed the diminished morphine dosage to the synergistic analgesic effect of bupivacaine.47 Although bupivacaine is a commonly used adjuvant medication, care should be taken to avoid concentrations greater than 0.75% in noncancer patients because neurotoxicity has been demonstrated at higher concentrations in rats receiving long-term infusions. Lidocaine (a local anesthetic) and clonidine (an alpha-adrenergic agonist) also have been given with morphine.

The morphine–clonidine combination seems to be particularly effective for patients with neuropathic or mixed nociceptive–neuropathic pain.32,36 In the mid-1990s, the Epidural Clonidine Study Group evaluated 85 patients with severe cancer pain who were taking large doses of opioids without significant pain relief or suffering from severe side effects. They were randomly assigned to receive 30 μg/hour of epidural clonidine or placebo for 14 days and had access to rescue epidural morphine. Pain was documented by visual analog score, McGill Pain Questionnaire, and daily epidural morphine use. Successful analgesia was reported by 45% of patients receiving clonidine, and by 21% receiving placebo. Among the patients with neuropathic pain, 56% receiving clonidine reported successful analgesia, as compared with only 5% receiving placebo. Pain scores were lower at the end of the study for the patients with neuropathic pain who received clonidine rather than placebo, and morphine use was unaffected. Serious hypotension occurred in two patients receiving clonidine and one receiving placebo.48 Clonidine has not yet been approved for intrathecal infusion in the United States, but in European and Australian studies, intraspinal infusion was well tolerated for 6–12 months.49,50 Dexmedetomidine, a highly selective new α2 adrenergic agonist, is known to produce sedation and analgesia in humans.51 Given intrathecally to rats, it is a very potent antinociceptor.52 Alpha-2 agonists also seem to potentiate the analgesic effects of opioids. One study in rats evaluated the interactions between systemically (subcutaneous, intravenous, and intraperitoneal) and spinally (epidural and intrathecal) administered α2 agonists (medetomidine, dexmedetomidine, xylazine, clonidine, and detomidine) and opioids (fentanyl or sufentanil).53 All of the tested α2 agonists potentiated the effects of opioids by reducing the amount of opioid needed to reach specified levels of analgesia and prolonging the duration of analgesia with a fixed dose of opioid. The potentiation appeared to be independent of the route of administration. Dexmedetomidine was second only to medetomidine in its ability to produce deep surgical analgesia when combined with fentanyl. Recent research that elucidates the neurobiology of pain suggests other methods of pain control. Nerve and tissue damage leads to changes in both the peripheral and central nervous system.

In one study, ziconotide exhibited substantial neuroprotective activity in a model of traumatic diffuse brain injury in rats.54 The effect of intrathecally administered ziconotide and morphine on nociception also has been studied in rats.55 After a 7-day intrathecal infusion, ziconotide enhanced morphine analgesia, but had no effect on ziconotide antinociception. Whereas chronic intrathecal morphine infusion led to rapid tolerance, ziconotide had no loss of analgesic potency during the infusion period.

Ziconotide administered with morphine produced a synergistic analgesic effect, but did not prevent morphine tolerance.55

In humans, ziconotide has been administered intrathecally to control acute postoperative pain.56 Mean daily morphine dosage (administered by patient-controlled analgesia) was significantly less in patients receiving ziconotide than in those receiving placebo 24–48 hours after surgery (p>0.040). Patient pain perception (measured by visual analog scale) also was markedly lower in patients treated with ziconotide than in patients treated with placebo. Four of six patients receiving the high dose of ziconotide (7 μg/hour) experienced adverse events including dizziness, blurred vision, nystagmus, and sedation, all of which resolved after drug discontinuation.

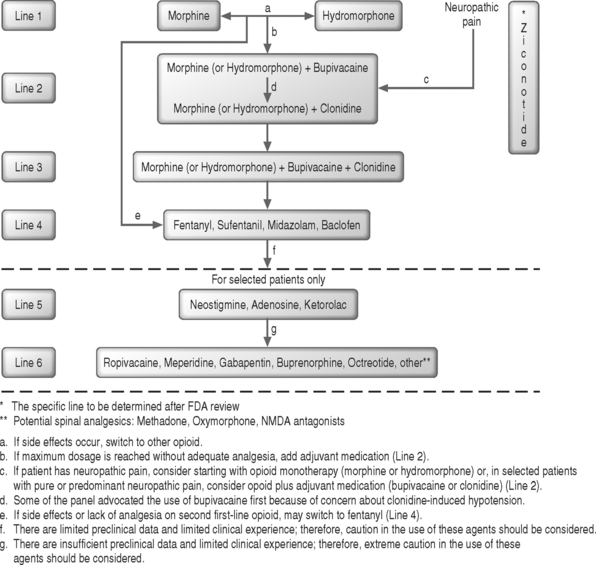

Ziconotide has also been used to treat cancer and AIDS patients experiencing pain not responsive to opioids.57 Intrathecal ziconotide has demonstrated analgesic efficacy, and the initial reports indicated that adverse events could be controlled with symptomatic treatment. An expert panel convened in July 2000 released clinical guidelines for intraspinal drug selection, dosage, and administration.58 The panel found wide variation in practice patterns on the basis of an Internet survey of physicians using implantable pumps. The guidelines reflect the best available evidence, as judged by experienced clinicians. In 2003, a similar meeting was convened and data from the intervening period were reviewed.59 The treatment recommendations are summarized in Figure 108.1. In 2007, a third panel met to review data from the intravening four years.59a The highlights of the new consensus statement include a change in the first line of therapy to include morphine, hydromorphone and ziconotide. The second line of therapy recommendations will also include ziconotide as an adjuvant option along with clonidine and bupivacaine. The panel also ranked other drugs in order of scientific support and clinical utility. A new important component was also developed for the 2007 version of the consensus panel which includes special recommendations for end of life care.59a The panel noted that the extensive preclinical and clinical data obtained as part of a formal drug development program exceeds the data available for other drugs used for intrathecal infusion and will probably lead to placement of ziconotide on an upper line of the algorithm, unless accumulating experience suggests a narrow therapeutic index in practice. Although the FDA approved ziconotide as an intrathecal monotherapy with a starting dose of 2.4 μg/d, a different, but overlapping consensus of experts expect that this medication will be used in conjunction with other intrathecal medications at a significantly lower staring dosage.60

Fig. 108.1 Clinical guidelines for intraspinal infusion, 2003.59

(The reader is referred to an updated recommended algorithm for intrathecal polyanalgesic therapies in a forthcoming publication, 2007.59a)

Efficacy

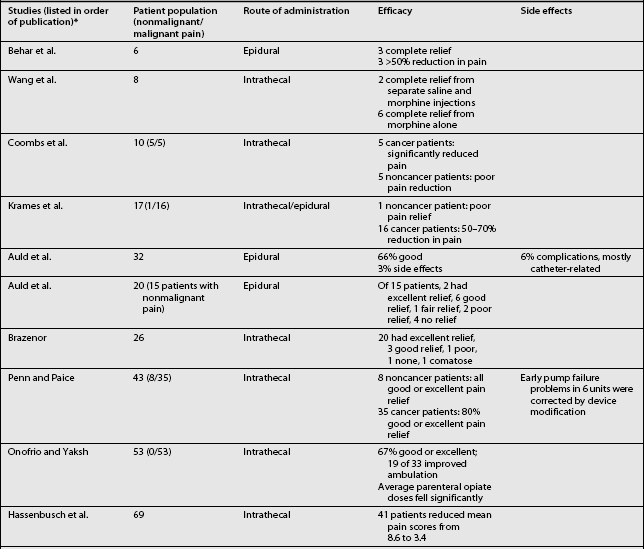

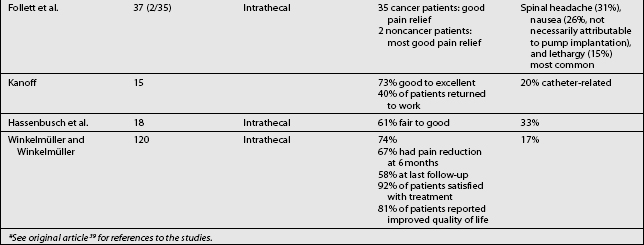

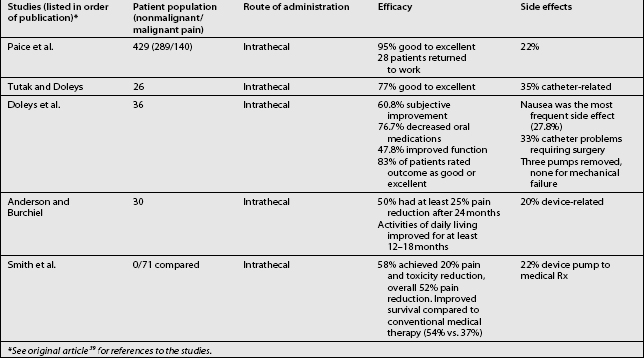

Studies on the efficacy of intraspinal morphine report widely ranging success rates for pain relief (Table 108.6).3,4–6,7,9,11–15,18,24,26,30,31,38,42,57,61–69 In general, pain relief for cancer patients occurred more frequently (in approximately 80% of cases) and consistently than for noncancer patients. Some studies also included other measures of efficacy, such as improvement in activities of daily living, employment status, and quality of life. In a cancer study, Smith et al. recently compared neuraxial delivery of morphine to maximum analgesic medical therapy in cancer patients and found that in addition to receiving better analgesia, the patients who received intrathecal morphine had greater longevity.69 Several key studies have examined the efficacy and reliability of intraspinal drug delivery. Winkelmüller and Winkelmüller68 investigated the long-term effects of continuous intrathecal infusion for chronic noncancer pain.

Tolerance developed in seven patients, three of whom had the pump removed. During the follow-up period, 74.2% of the patients benefited from intrathecal opioid delivery. The average pain reduction was 67.4% after 6 months and 58.1% at last follow-up examination. Most patients (92%) were satisfied with therapy, and 81% reported improvement in quality of life. Angel et al.70 studied 11 patients (9 with FBSS) referred to a neurosurgery clinic and treated with intrathecal morphine. The patients were observed for up to 3 years. Overall, a good to excellent analgesic response was seen in 73% (8/11) of the patients. Unfortunately, the three patients judged to have poor results all had FBSS. The effective response among all the FBSS patients was 67% (6/9). Bladder dysfunction requiring pump removal occurred in two patients. The authors concluded that intrathecal morphine delivery was a viable alternative in the management of FBSS despite its limitations. They cautioned that it should be a last-choice option.

In the most recent study in FBSS patients, The National Outcomes Registry for Low Back Pain collected prospective data on 136 patients with chronic low back pain treated using intraspinal infusion via implanted devices, 81% of whom received morphine. Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Scale ratings after 12 months improved by 47% in patients with back pain and by 31% in patients with leg pain.71 The largest study, a retrospective, multicenter study, surveyed physicians in the United States regarding intrathecal morphine delivered by the SynchroMed pump.64 In this study, 35 physicians provided 429 case reports detailing screening methods, outcomes, dosing, and adverse effects. Each of the physicians contacted had implanted at least five pumps. Among these patients, 33% were being treated for cancer pain and 67% for noncancer pain. The average length of treatment was 14.6±0.57 months. The patients with somatic pain had the degree of pain relief. After initial dose titration, intrathecal morphine doses increased only twofold, from 5.84±0.65 mg/d to 13.19±1.76 mg/d. The patients being treated for cancer pain had a higher initial dose, which escalated quickly and then reached a plateau. Patients with noncancer pain had a gradual, linear increase in dosage. Adverse drug effects were not frequent, but catheter or system malfunction occurred in 21.6% of the cases. Although most implantable drug delivery systems are used to treat nociceptive pain, in the Hassenbusch et al. study38 of intraspinal drug therapy for patients with severe neuropathic pain, 11 of 18 patients (61%) had good or fair pain relief after more than 2 years. Average numerical pain scores declined by 39±4.3%, although long-term pain relief eventually fai™led for 7 of 18 patients (39%). The authors concluded that long-term intrathecal opioid infusions could be effective for treating neuropathic pain, but at higher doses than used for treating nociceptive pain.

A recent prospective study examined the long-term safety and efficacy of intrathecal morphine for patients with severe noncancer pain.61 Of 40 patients, 30 experienced pain relief during a screening trial and had an intraspinal delivery system implanted. Patients had mixed neuropathic–nociceptive pain (50%), peripheral neuropathic pain (33%), deafferentation pain (13%), or nociceptive pain (3%). Half of the patients (11/22) reported at least a 25% reduction on the visual analog scale after 24 months of treatment. The results of the McGill Pain Questionnaire and Chronic Illness Problem Inventory showed improvement in sleep, social activities, inactivity levels, and medication use throughout the follow-up period. Device-related problems requiring additional surgery were experienced by 20% of the patients.

COMPLICATIONS

The complications of intraspinal therapy fall into several categories: procedure-related complications, drug-related side effects, and equipment-related problems. Immediate drug-related side effects include nausea and vomiting, urinary retention (more common in men with benign prostatic hypertrophy), pruritus, and respiratory depression. Each of these conditions can be managed medically with antiemetics, intermittent catheterization, antihistamines, or naloxone, respectively. Respiratory depression, the most serious of these side effects, is relatively rare in patients already exposed to opioids. Delayed side effects include constipation, myoclonus, edema, arthralgias, facial flushing, and diaphoresis. Clinicians increasingly recognize suppression of the hypothalamic–pituitary axis producing endocrine changes.

Examples include decreased testosterone production resulting in decreased libido and suppression of thyroid function resulting in hypothyroidism. For this reason, serum lipids, androgens or estrogens, 24-hour urinary cortisol, and serum IGF-1 levels should be monitored during intrathecal therapy.72 Intraspinal therapy requires conscientious follow-up evaluation, with doses adjusted to balance pain relief against side effects. Many side effects respond to symptomatic treatment.37

Unintentional overdosing can be disastrous. Symptoms of massive morphine overdose include muscle rigidity, severe myoclonus, seizure activity, hypertension, cardiovascular collapse, and severe respiratory depression. Should an overdose occur, the patient should be hospitalized immediately. Replacing some CSF with saline and administering naloxone if signs of respiratory depression occur may help.36

Catheter-related problems are common, occurring in 10–40% of cases. Any abrupt change in pain can signal a catheter problem.34,37 Troubleshooting for equipment problems demands all of a physician’s diagnostic and management skills. A radiograph of the pump and catheter will disclose many catheter problems, but not whether the tip is obstructed or a CSF leak has occurred. Often, surgical inspection and correction are required.36 Meticulous surgical technique can help to prevent some catheter problems. Catheter position can be checked fluoroscopically, CSF flow confirmed at each step during implantation, and the catheter secured with a purse-string suture at the interspinous ligament, and again with a plastic fixation device.34

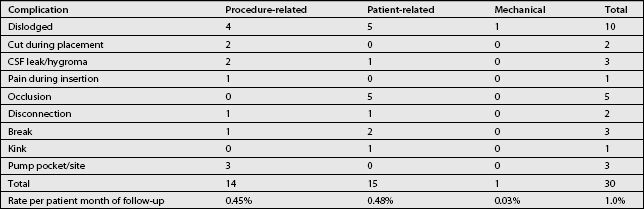

A recent prospective study of 202 patients in 22 centers in the United States and Europe examined results from the use of a catheter5 modified to overcome some drawbacks of earlier designs.42 The patients in this study were being treated for noncancer pain (60.4%), spinal spasticity (21.8%), cancer pain (12.4%), or other conditions.

The catheter implantation technique varied widely with regard to catheter entry site and tip position, spinal introducer position, and catheter anchoring. Based on 3112.8 months of patient use, the overall catheter-caused complication rate was 0.3% per patient per month. More than 89% of the physicians rated the new catheter as superior to previously available catheters. Table 108.7 lists the nonmedication-related complications associated with this new catheter. Cerebrospinal fluid leaks are inevitable during intrathecal catheter placement, leading to postspinal headache in up to 20% of patients. Persistent CSF leaks should be treated with autologous epidural blood patching.

Cerebrospinal fluid hygromas usually resolve spontaneously, but surgical intervention may be necessary if fluid persistently leaks through the suture line after more conservative measures have failed.36

Catheter-tip granulomas, often associated with neurologic sequelae, may develop after intraspinal catheter placement.72 Granulomas are relatively rare. In a survey of 519 US physicians who implanted drug delivery systems, 31 reported a total of 19 cases, 6 of which had not been previously reported in the literature.65 Two reported cases involved patients with FBSS.73,74 Patients with a granulomatous mass may present with new pain, numbness, weakness, or changes in bowel and bladder habits. A recent study analyzed reports of catheter-tip inflammatory masses (granulomas) in 39 patients who received intrathecal morphine or hydromorphone, either alone or mixed with other drugs.75 The authors noted that patients whose mass was diagnosed during the administration of drugs other than intrathecal morphine had probably been exposed to morphine earlier in their clinical course. Subsequently, based on this and preclinical studies, Hassenbusch led a consensus conference that recommended positioning of the catheter tip in the lumbar thecal sac, minimizing opioid dosage and concentration to the extent possible, and providing attentive follow-up of patients to encourage early diagnosis and to reduce the risk of neurological injury.76

The diagnosis of granuloma is confirmed by a neurologic examination and MRI. Treatment consists of surgical decompression and removal of the mass and spinal catheter.72 Prevention trumps treatment in the management of surgical infections. Prophylactic cephalosporin or vancomycin administration is recommended, along with strict sterile technique. A wound should never be closed in the presence of uncontrolled bleeding because hematomas are active breeding grounds for infections. Epidural hematoma, diagnosed by MRI or computed tomography (CT), should be treated as an emergency if it impairs neurologic function. Superficial wound infections can be treated with appropriate antibiotics. The implant must be removed if infection invades the catheter or implant pocket. After exploration, the wound should be packed and left open to heal. Intrathecal infections are rare, although many patients spike a fever within the first 3 days after implantation. The most recent information regarding intrathecal granuloma is summarized in the paper from the Polyanalgesic Consensus Conference 200772a. Of note is the fact that the lowest incidence of granuloma is reported with intrathecal fentanyl and baclofen (possibly concentration related).

If the complete blood count is normal, the CSF shows only leukocytosis, and the fever falls within 48–72 hours, meningitis probably is not a concern. Untreated epidural infections can abscess and compress the thecal sac, potentially leading to paralysis. Diagnosis relies on clinical signs and symptoms, confirmed by MRI or CT studies. Epidural abscess is treated by removing the pump and catheter and administering antibiotics. Consultation with an infectious disease specialist can be helpful in the selection of antibiotics.36

Many patients notice pump pocket seroma for several months after implantation. The use of postoperative abdominal binders may decrease the incidence and severity of this problem. When seroma persists, fluid can be aspirated for Gram staining if infection is suspected. Intravenous antibiotics and antibiotic irrigation of the pocket can be performed for proven bacterial infection. Patients should be monitored carefully for the spread of infection during treatment, and the device must be removed if the infection does not respond to treatment.36

TROUBLESHOOTING FOR LACK OF EFFICACY

Caveat 2

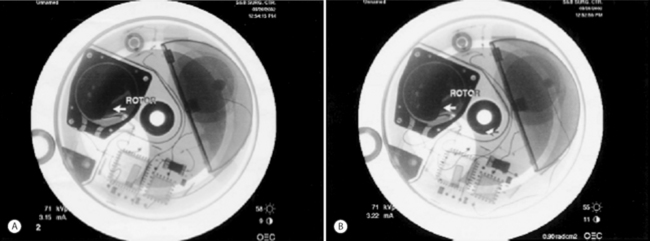

Distribution of the contrast solution can demonstrate proper flow within the CSF, verifying catheter function. Pump function (proper pump roller rotation) can be observed under fluoroscopic guidance. Figure 108.2A demonstrates the original position of the pump rotor prior to rotor rotation. Figure 108.2B demonstrates rotation of the rotor. For cases in which conventional contrast radiography leads to a confusing picture, radiolabeled indium can be injected, with the result that serial scans over the ensuing 12–24 hours will show diffusion through the CSF if the catheter is positioned intrathecally.

IMPLANTED PUMPS AND RADIOLOGIC PROCEDURES

Patients with FBSS may require diagnostic procedures such as CT or MRI scans. Questions frequently arise regarding the advisability of performing scans for patients with implanted devices. There are no special implications for plain radiographs or CT scans. With modern fixed-rate pumps, exposure of pumps to MRI fields of 1.51 Tesla has demonstrated no impact on pump performance and a limited effect on the quality of the diagnostic information.

For patients with implanted programmable pumps, the manufacturer recently released a document stating that the magnetic field of the MRI scanner will temporarily stop the rotor of the pump motor and suspend drug infusion for the duration of MRI exposure. The pump should resume normal operation on termination of MRI exposure. Before MRI, the physician should determine if the patient could safely be deprived of drug delivery. If the patient cannot be safely deprived of drug delivery, alternative delivery methods for the drug can be used during the time required for the MRI scan. If there is concern that suspension of drug delivery during the MRI procedure may be unsafe for the patient, medical supervision should be provided while the MRI is conducted. Before scheduling an MRI scan and on completion of the MRI scan, or shortly thereafter, the pump status should be confirmed using the SynchroMed programmer. In the unlikely event that any change to the pump status has occurred, a Pump Memory Error message will be displayed and the pump will sound a Pump Memory Error Alarm (double tone). The pump should then be reprogrammed and Technical Services notified.66

FUTURE CHALLENGES

Microprocessors and miniaturization have enhanced pump development. Programmable pumps are now limited by battery life constraints and size. Improvements in power sources will expand the lifespan of programmable pumps and decrease their size, allowing for larger reservoir volume. At this writing, only one implantable intrathecal system provides an element of patient control and it is not FDA approved for use in the United States. The current pumps are effective in treating baseline pain, but a system that allows patient control for breakthrough pain is essential. Finally, given the contrast in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the various medications that will be used simultaneously in pumps in the future, a system that can deliver different medications at different rates would be desirable. A review of experimental drugs undergoing study can be found in the Intradisciplinary Polyanalgesic Consensus Conference 2007.77

1 Prager J, Jacobs M. Evaluation of patients for implantable pain modalities: medical and behavioral assessment. Clin J Pain. 2001;17:206-214.

2 Hughes J, Smith TW, Kosterlitz HW, et al. Isolation of two related pentapeptides from brain with potent opiate activity. Nature. 1975;258:577-580.

3 Pert CB, Snyder S. Opiate receptors demonstration in nervous tissue. Science. 1973;179:1011-1014.

4 Behar M, Olshwant D, Magor F, et al. Epidural morphine in treatment of pain. Lancet. 1979;1:527-529.

5 Wang JF, Nauss LA, Thomas JE. Pain relief by intrathecally applied morphine in man. Anesthesiology. 1979;50:149-151.

6 Brazenor GA. Long-term intrathecal administration of morphine: A comparison of bolus injection via reservoir with continuous infusion by implanted pump. Neurosurgery. 1987;21:484-491.

7 Coombs DW, Saunders RL, Gaylor MS, et al. Relief of continuous chronic pain by intraspinal narcotics infusion via an implanted reservoir. JAMA. 1983;250:2336-2339.

8 Dennis GC, DeWitty RL. Management of intractable pain in cancer patients by implantable morphine infusion systems. J Natl Med Assoc. 1987;79:939-944.

9 Follett KA, Hitchon PW, Piper J. Response of intractable pain to continuous intrathecal morphine: A retrospective study. Pain. 1992;49:21-25.

10 Harbaugh RE, Coombs DW, Saunders RL, et al. Implanted continuous epidural morphine infusion system. J Neurosurg. 1982;56:803-806.

11 Krames ES, Gershow J, Glassberg A, et al. Continuous infusion of spinally administered narcotics for the relief of pain due to malignant disorders. Cancer. 1985;56:696-702.

12 Onofrio BM, Yaksh TL. Long-term pain relief produced by intrathecal infusion in 53 patients. J Neurosurg. 1990;72:200-209.

13 Penn RD, Paice JA. Chronic intrathecal morphine for intractable pain. J Neurosurg. 1987;67:182-186.

14 Shetter AG, Hadley MN, Wilkinson E. Administration of intraspinal morphine sulfate for the treatment of cancer pain. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:740-747.

15 Spaziante R, Cappabiance P, Ferone A. Treatment of chronic cancer pain by means of continuous intrathecal low-dose morphine administration with a totally implantable subcutaneous pump. J Neurosurg Sci. 1985;29:143-151.

16 Varga CA. Chronic administration of intraspinal local anesthetics in the treatment of malignant pain. Proc Am Pain Soc. 1989:71.

17 Zimmerman CG, Burchiel KM. The use of intrathecal opiates for malignant and nonmalignant pain: Management of thirty-nine patients. Proc Am Pain Soc. 1991:97.

18 Auld AW, Maki-Jokela A, Murdoch DM. Intraspinal narcotic analgesia in the treatment of chronic pain. Spine. 1984;10:777-781.

19 Barolat G, Schwartzman RJ, Aries I. Chronic intrathecal morphine infusion for intractable pain in reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Proc Am Pain Soc. 1988:17.

20 Bedder MD, Olson KA, Flemming BM, et al. Diagnostic indicators for implantable infusion pumps in nonmalignant pain. Proc Am Pain Soc. 1992:111.

21 Burchiel KJ, Johans TJ. Management of postherpetic neuralgia with chronic intrathecal morphine. Proc Am Pain Soc. 1992:136.

22 Goodman RR. Treatment of lower extremity reflex sympathetic dystrophy with continuous intrathecal morphine infusion. Appl Neurophysiol. 1987;50:425-426.

23 Hadley MN, Shetter AG. Intrathecal opiate administration for analgesia. Contemp Neurosurg. 1986;8:1-6.

24 Hassenbusch SJ, Stanton-Hicks MD, Soukup J, et al. Sufentanil citrate and morphine/bupivacaine as alternative agents in chronic epidural infusions for intractable noncancer pain. Neurosurgery. 1991;29:76-82.

25 Jacobson L. Clinical note: Relief of persistent postamputation stump and phantom limb pain with intrathecal fentanyl. Pain. 1989;37:317-322.

26 Kanoff RBL. Intraspinal delivery of opiates by an implantable, programmable pump in patients with chronic, intractable pain of nonmalignant origin. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1994;94:487-493.

27 Krames ES, Lanning RM. Intrathecal infusion analgesia for nonmalignant pain. Proc Am Pain Soc. 1991:98.

28 Krames ES, Lanning RM. Intrathecal infusional analgesia for nonmalignant pain: Analgesic efficacy of intrathecal opioid with or without bupivacaine. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1993;8:539-548.

29 Lamb SA, Hosobuchi Y. Intrathecal morphine sulfate for chronic benign pain, delivered by implanted pump delivery systems. Proc Intl Assoc Study Pain. 1990:S120.

30 Prager JP, DeSalles A, Wilkinson A, et al. Loin pain hematuria syndrome: Pain relief with intrathecal morphine. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;25:629-631.

31 Portenoy RK. Current pharmacotherapy of chronic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19(1 Suppl):S16-S20.

32 Krames ES, Olson K. Clinical realities and economic considerations: Patient selection in intrathecal therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;14:S3-S13.

33 Ferrante FM. Neuraxial infusion in the management of cancer pain. Oncology. 1999;13(5 Suppl 2):30-36.

34 Levy RM, Salzman D. Implanted drug delivery systems for control of chronic pain. In: North RB, Levy RM, editors. Neurosurgical management of pain. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1997:302-324.

35 DuPen SL, Peterson DG, Bogosian AC, et al. A new permanent exteriorized epidural catheter for narcotic self-administration to control cancer pain. Cancer. 1987;59:986-993.

36 Krames E. Intraspinal opioid therapy for chronic nonmalignant pain: Current practice and clinical guidelines. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1996;11:333-352.

37 Gianino JM, York MM, Paice JA. Intrathecal drug therapy for spasticity and pain. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1996.

38 Hassenbusch SJ, Stanton-Hicks M, Covington EC, et al. Long-term intraspinal infusions of opioids in the treatment of neuropathic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10:527-543.

39 Prager JP. Neuraxial medication delivery. the development and maturity of a concept for treating pain of spinal origin. Spine. 2002;27:2593-2605.

40 Medicare Conditions for Coverage, Medicare Coverage Issues Manual, February. Transmittal No. 67, Section 40-14, 1994.

41 Caudill MA, Holman GH, Turk D. Effective ways to manage chronic pain. Patient Care. 1996;31:154-166.

42 Prager J, et al. Behavioral evaluation of patients for significant pain interventions. Presented at the American Pain Society Professional Development Course, October, 2000.

43 Krames ES, Chapple I, the 8703 W Catheter Study Group. Reliability and clinical utility of an implanted intraspinal catheter used in the treatment of spasticity and pain. Neuromodulation. 2000;3:7-14.

44 Follett KA, Burchiel K, Deer T, et al. Prevention of intrathecal drug delivery catheter-related complications. Neuromodulation. 2003;6(1):32-41.

45 York M, Paice JA. Treatment of low back pain with intraspinal opioids delivered via implanted pumps. Orthop Nurs. 1998;17:61-69.

46 van Dongen RT, Crul BJ, DeBock M. Long-term intrathecal infusion of morphine and morphine/bupivacaine mixtures in the treatment of cancer pain: A retrospective analysis of 51 cases. Pain. 1993;55:119-123.

47 van Dongen RT, Crul BJ, van Egmond J. Intrathecal coadministration of bupivacaine diminishes morphine dose progression during long-term intrathecal infusion in cancer patients. Clin J Pain. 1999;15:166-172.

48 Eisenach JC, DuPen S, Dubois M, et al. Epidural clonidine analgesia for intractable cancer pain. Pain. 1995;61:391-399.

49 Hassenbusch SJ. Epidural and subarachnoid administration of opioids for nonmalignant pain: Technical issues, current approaches, and novel treatments. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1996;11:357-362.

50 Krames ES. Intrathecal infusion therapies for intractable pain: Patient management guidelines. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1993;8:36-46.

51 Guo TZ, Jiang JY, Buttermann AE, et al. Dexmedetomidine injection into the locus ceruleus produces antinociception. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:873-881.

52 Kalso EA, Poyhia R, Rosenberg PM. Spinal antinociception by dexmedetomidine, a highly selective alpha 2-adrenergic agonist. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1991;68:140-143.

53 Meert TF, De Kock M. Potentiation of the analgesic properties of fentanyllike opioids with alpha 2-adrenoceptor agonists in rats. Anesthesiology. 1994;81:677-688.

54 Berman RF, Verweu BH, Muizelaar JP. Neurobehavioral protection by the neuronal calcium channel blocker ziconotide in a model of traumatic diffuse brain injury in rats. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:821-828.

55 Wang YX, Gao D, Pettus M, et al. Interactions of intrathecally administered ziconotide, a selective blocker of neuronal N-type voltage-sensitive calcium channels, with morphine on nociception in rats. Pain. 2000;84:271-281.

56 Atanassoff PG, Hartmannsgruber MW, Thrasher J, et al. Ziconotide, a new N-type calcium channel blocker, administered intrathecally for acute postoperative pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2000;25:274-278.

57 Penn RD, Paice JA. Adverse effects associated with the intrathecal administration of ziconotide. Pain. 2000;85:291-296.

58 Bennett G, Burchiel K, Buchser E, et al. Clinical guidelines for intraspinal infusion: Report of an expert panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20:S37-S43.

59 Hassenbusch S, et al. Polyanalgesic Consensus Conference 2003: An update on the management of pain by intraspinal drug delivery-report of an expert panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;27(6):540-563.

59a Deer T, Krames ES, Hassenbusch S, et al. Polyanalgesic Consensus Conference 2007: Recommendations for the Management of Pain by Intrathecal (Intraspinal) Drug Delivery. Report of an Intradisciplinary Expert Panel. In Press 2007.

60 Willis D, et al. Expert Consensus of dosing and use of Ziconotide [Editorial in press]. Neuromodulation June 2005.

61 Anderson VC, Burchiel KJ. A prospective study of long-term intrathecal morphine in the management of chronic nonmalignant pain. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:289-301.

62 Auld AW, Maki-Jokela A, Murdoch DM. Intraspinal narcotic analgesia: Pain management in the failed laminectomy syndrome. Spine. 1987;12:953-954.

63 Doleys DM, Coleton, Tutak U. Use of intraspinal infusion therapy with non-cancer pain patients: Follow-up and comparison of worker’s compensation vs. nonworker’s compensation patients. Neuromodulation. 1998;1:149-159.

64 Paice JA, Penn RD, Shott S. Intraspinal morphine for chronic pain: A retrospective, multicenter study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1996;11:71-80.

65 Schuchard M, Lanning R, North R, et al. Neurologic sequelae of intraspinal drug delivery systems: Results of a survey of American implanters of implantable drug delivery systems. Neuromodulation. 1998;1:137-148.

66 Schueler BA, Parrish TB, Lin J-C, et al. MRI compatibility with and visibility assessment of implantable medical devices. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;9:596-603.

67 Tutak U, Doleys DM. Intrathecal infusion systems for treatment of chronic low back and leg pain of noncancer origin. South Med J. 1996;89:295-300.

68 Winkelmüller M, Winkelmüller W. Long-term effects of continuous intrathecal opioid treatment in chronic pain of nonmalignant etiology. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:458-467.

69 Smith TJ, Staats PS, Deer T, et al. Randomized clinical trial of an implantable drug delivery system compared with comprehensive medical management for refractory cancer pain: Impact on pain, drug-related toxicity, and survival. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4040-4049.

70 Angel IF, Gould HF, Carey ME. Intrathecal morphine pump as a treatment option in chronic pain of nonmalignant origin. Surg Neurol. 1998;49:92-98.

71 Deer T, Chapple I, Classen A, et al. Intrathecal drug delivery for treatment of chronic low back pain: Report from the National Outcomes Registry for Low Back Pain. Pain Med. 2004;5:6-13.

72 Naumann C, Erdine S, Koulousakis A, et al. Drug adverse events and system complications of intrathecal opioid delivery for pain: Origins, detection, manifestations, and management. Neuromodulation. 1999;2:92-107.

72a Deer T, Krames ES, Hassenbusch S, et al. Management of intrathecal catheter-tip inflammatory masses: an updated 2007 Consensus Statement from an Expert Panel. In Press, 2007.

73 Koulousakis A, Imdahl M, Weber M. Continuous intrathecal application of morphine in cancer pain. Proceedings of the 8th World Congress, 1998.

74 North RB, Cutchis PN, Epstein JA, et al. Spinal cord compression complicating subarachnoid infusion of morphine: Case report and laboratory experience. Neurosurgery. 1991;29:778-784.

75 Coffey RJ, Burchiel K. Inflammatory mass lesions associated with intrathecal drug infusion catheters: Report and observations on 41 patients. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:78-87.

76 Hassenbusch S, Burchiel K, Coffey R, et al. Management of intrathecal catheter-tip inflammatory masses: A consensus statement. Pain Med. 2002;3:313-323.

77 Deer T, Krames ES, Hassenbusch S, et al. Experimental drugs for intrathecal pain management: a review and update from the Interdisciplinary Polyanalgesic Consensus Conference 2007. In press, 2007.