CHAPTER 88 Surgery for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a common psychiatric condition and is categorized as an anxiety disorder.1 OCD occurs in approximately 2% of the population at some point in life.2 It can result in considerable disability,3 and the World Health Organization ranks OCD as the 10th leading cause of disability worldwide.4 OCD is typically characterized by obsessions and compulsions. Obsessions are intrusive and unwanted thoughts, impulses, or images that occur outside of one’s control and generate significant anxiety. Compulsions are stereotyped motor, cognitive acts, and rituals that are performed in an attempt to relieve the anxiety. Importantly, OCD thoughts and behavior are usually recognized by patients as unreasonable, irrational, and unnecessary, even though they cannot avoid or stop them. OCD symptoms are heterogeneous and can be complex. A patient may have obsessive thoughts of having been contaminated by touching certain objects. This obsession generates substantial anxiety and fear in the individual. The anxiety is not relieved unless a certain ritualized behavior such as extensive hand washing is undertaken. Other patients may fear that some action that they failed to take may result in injury to someone else. A frequent OCD symptom is obsessive concern over leaving the stove on or items plugged in when leaving the house. In the mind of the OCD sufferer, this could result in a fire and subsequent injury to other people, pets, or property. Anxiety builds until a checking ritual (hours in length in severe cases) is performed to the satisfaction of the patient. Examples of other obsessions include those involving symmetry, religious concerns, or sexual issues. Compulsive behavior can include washing, checking, mental rituals, counting, praying, hoarding, or ordering objects. To meet the diagnostic criteria for OCD, patients must typically spend an hour or more per day on their obsessions or compulsions, or on both; however, patients with severe OCD may spend the majority of their waking hours focused on their symptoms.

Treatment

Treatment of OCD includes medications in conjunction with psychotherapy or cognitive behavioral therapy. These interventions typically do not result in complete eradication of symptoms, and patients may require a variety of medications, as well as multiple sessions of cognitive behavioral therapy, to improve. The disorder is so resistant to treatment that a positive “response” in clinical trials of OCD therapy is often defined as a 35% or greater improvement measured with standardized clinical rating scales.5 The form of psychotherapy used in treating OCD is known as exposure/response prevention therapy. It involves exposing patients to their anxiety-producing situation (i.e., touching a “contaminated” object) and then preventing the typical response (i.e., excessive hand washing).6 This form of therapy is often the most effective and has been shown to induce changes in brain activity that correlate with symptomatic response.7,8 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are currently the most effective medications for the treatment of OCD.9 If significant benefit is not achieved with adequate doses of an SSRI, other medications such as clonazepam, risperidone, buspirone, or other atypical antipsychotics may be added.10 Despite optimal medical and psychotherapeutic interventions, at least 20% of patients remain refractory to treatment. Of these individuals, half are completely debilitated by their illness.11 It is these suffering patients with few treatment options who may be candidates for neurosurgical intervention.

Neural Circuitry of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

The anatomic basis of behavior and its implications for understanding psychiatric disease have intrigued neuroscientists for a long time. Nineteenth century phrenologists such as Franz Gall attempted to attribute personality traits and faculties of the mind to the degree of development of different cerebral areas, which could be inferred from the skull’s shape and features.12 Early animal experiments performed in the 19th century suggested that injury to the temporal lobes could alter aggressive behavior in animals. The importance of the frontal lobes to human behavior became increasingly apparent from observing patients with diseases or injuries in that region. One of the most famous examples is that of Phineas Gage, a railroad worker who suffered a frontal lobe injury when an iron rod penetrated his left skull base and exited at the vicinity of the coronal suture.13,14 Gage survived his injury but suffered from significant changes in behavior and personality. Gage, who had previously been regarded as efficient and capable, became “irreverent, indulging in the grossest profanity and … manifesting but little deference for his fellows … that his friends and acquaintances said he was no longer Gage.”15,16 Several decades later, Carlyle Jacobsen and John Fulton demonstrated that injury to both frontal lobes in a nonhuman primate resulted in improvement of “neurosis” and tantrum fits that would previously occur in response to frustration.17,18 These findings provided the experimental rationale for Egaz Moniz and Almeida Lima’s exploration of frontal leukotomy as a treatment of human psychiatric illness.19,20 Moniz’s work popularized psychosurgery and resulted in him being awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1949. Unfortunately, the rapid adoption and indiscriminate and widespread use of frontal lobotomy in the following years resulted in significant controversy that ultimately limited the proper development of surgical approaches to psychiatric disorders.

In response to this checkered history, modern research on psychosurgery is performed by multidisciplinary teams in a controlled fashion, with monitoring committees to ensure patient safety.21,22 Significant advances have been made in understanding the key neurobehavioral networks that control anxiety, behavior, and emotions. One important network is located in the anterior frontal lobes with connections to the thalamus and basal ganglia. Another key network with important implications for surgical treatment of psychiatric disease is the limbic system. Early descriptions of the limbic lobe were made by Paul Broca in the second half of the 19th century.17 Subsequently, James Papez’s landmark 1937 publication implicated a circuit involving the hippocampus, cingulate gyrus, hypothalamus, anterior thalamus, and fornix in the elaboration and expression of emotion.23,24 Experiments by MacLean elucidated the concept of the limbic system and described its role in the control of behavior and emotion.25,26 The rationale for surgical interventions for OCD and other psychiatric disorders is to alter the abnormal function of the limbic system, as well as the networks connecting the prefrontal cortex to the thalamus and ventral basal ganglia, by ablation or chronic electrical stimulation.27,28

The functional organization of the connections among the cortex, striatum, globus pallidus, and thalamus is similar in movement disorders and psychiatric disorders. The current view that parallel basal ganglia–thalamic loops process cortical input originating in motor, oculomotor, dorsolateral prefrontal, lateral orbitofrontal, or anterior cingulate areas has been established by Alexander and colleagues.29 Modern staining techniques and histologic studies led to identification of the ventral pallidal system, a key milestone in understanding parallel basal ganglia networks.30,31 Likewise, modern histologic methods allowed identification of the extended amygdala system.32

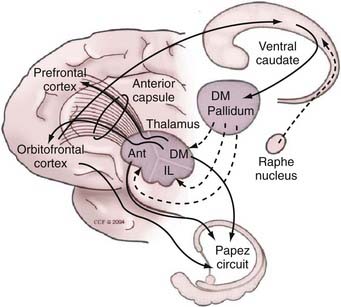

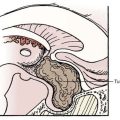

In the current view of the network (Fig. 88-1), the cortical-striatal-pallidal-thalamic-cortical (CSPTC) loop related to neurobehavioral and psychiatric disease originates in the prefrontal and orbital frontal cortices and, along with the parallel circuit originating at the cingulate cortex, controls behavior and emotion. In the orbitofrontal system, projections enter the basal ganglia through the ventral internal capsule and ventral striatum, which in turn project to the ventral pallidum. In addition to the corticostriatal projections, reciprocal direct connections also exist between the orbitofrontal cortex and the thalamus and are conveyed through the anterior limb of the internal capsule. Projections from the orbitofrontal cortex reach the ventral striatal area, which is composed predominantly of the ventral aspect of the caudate nucleus and the nucleus accumbens, with excitatory terminals mediated by glutamate. The ventral striatum also receives projections from the hippocampus and the amygdala and is further divided into two territories: the shell and core. In humans, the inner core is composed of calbindin-rich neurons, whereas the shell is populated predominantly by calbindin-poor cells.33 Both the ventral pallidum and the ventral striatum are located ventral to the anterior commissure, near the anterior perforated substance. Ventral striatal projections to the ventral pallidum are mediated predominantly by substance P, enkephalin, and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). The external part of the ventral pallidum, like the pars externa of the dorsal component of the globus pallidus, projects preferentially to the subthalamic nucleus.34,35 The internal segment has inhibitory projections predominantly to the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus.33,36,37 This differs from the projections mediating motor control, which are processed through ventrolateral thalamic nuclei.

The parallel segregated circuitry model is important for our current understanding of how information is processed through the basal ganglia and how the cortical activity associated with each domain of motor or nonmotor functioning is modulated. The segregation of these circuits, however, is not absolute. Cortical-fugal connections tend to overlap, particularly in the ventral striatum.31 Furthermore, recent evidence has shown specific points of connectivity among these otherwise segregated loops that allow the integration of motor, cognitive, and limbic functions.38

The neuroanatomic CSPTC circuit has served as a substrate for mechanistic models of the pathophysiology of OCD. Modell and collaborators proposed that pathologic states may arise when the orbitofrontal and corticothalamocortical loops, which exchange reciprocal excitatory connections via the anterior limb of the internal capsule, lose their physiologic modulation. Normally, this modulation is maintained by projections through the ventral striatum and pallidum. The net effect of this longer modulatory loop is thalamic inhibition through the pallidothalamic GABAergic projections. In the normal state, this inhibition serves to “damp the excitatory orbitofrontal-thalamic reciprocating circuit.”39 However, in OCD, there is a lack of regulation of the excitatory loop that results in an overactive orbitofrontal cortex. Neuroimaging studies in patients with OCD have provided support for this model. Baxter and colleagues identified increased orbitofrontal and striatal metabolic activity in patients with OCD undergoing fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET).40 Subsequent studies have provided further supportive evidence for the model by demonstrating hyperactivity of the caudate nucleus in patients with OCD. More importantly, a reduction in this hyperactivity was observed in OCD patients who responded well to behavioral therapy.41 Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has also contributed to our understanding of the neural circuitry of OCD. Study paradigms have included a comparison of hemodynamic responses in different cortical and subcortical structures, with and without provocation of symptoms42,43 and during cognitive tasks.44 Activation of several cortical areas, including the cingulate cortex, temporal lobes, and orbitofrontal areas, has been demonstrated,45 again corroborating the participation of these networks in the pathogenesis of OCD. Recent functional neuroimaging studies have explored the possibility that discrete behavioral features of OCD could be predominantly modulated by different anatomic substrates.46 Mataix-Cols and coworkers assessed the response of OCD patients and normal volunteers to images depicting scenes related to contamination or washing and checking or hoarding behavior.47 In response to pictures depicting washing, patients demonstrated greater activation in the ventromedial prefrontal regions and right caudate nucleus than controls did. Images related to checking behavior increased activation of the lentiform nucleus and thalamus, whereas those related to hoarding resulted in increased activation of the right orbitofrontal region. This study supports previous knowledge indicating the relevance of the CSPTC loop to the genesis of OCD and demonstrates that different anatomic substrates may be involved in discrete OCD symptoms. fMRI studies have also been performed in OCD patients with externalized deep brain stimulation (DBS) leads to allow exploration of the effects of stimulation of the targeted area on the pathologic circuit.48

Ablative Procedures for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Prefrontal leukotomy was an early, undeveloped surgical approach that represented the initial human extension of early-stage animal research.49,50 The initial Moniz experience19 was deemed sufficient and the procedure was quickly adopted and performed widely for various conditions without standardized indications, outcome measures, or follow-up.51

Cingulotomy

Cingulotomy has been the most commonly performed neurosurgical procedure for OCD in the United States.52,53 The rationale for cingulotomy as a treatment of psychiatric disease derives from the determination that the cingulate gyrus is an important part of the limbic system. Results of animal experimentation and the early insights of Fulton were also important in development of the cingulum as a surgical target.28 The first series of stereotactic cingulotomy for OCD relied on ventriculographic target localization28; however, ventriculography has been supplanted by MRI for targeting,52 in conformity with stereotactic procedures in general.54,55 The radiofrequency-generated thermal lesions are targeted on the cingulate gyrus, dorsal to the roof of the lateral ventricle and posterior to the anterior limit of the frontal horn of the lateral ventricle.52,56 It is not uncommon for patients to require additional cingulate gyrus lesions placed anterior to the initial lesions to achieve the desired effect.57 These additional lesions can be performed during the initial procedure or at a later date after observing the results of single lesions. In some cases, subcaudate lesions can be added to the cingulotomies, thereby transforming the operation to a limbic leukotomy (see later).52

Cingulotomy has been shown to be safe in the hands of expert stereotactic surgeons working in close collaboration with experienced psychiatry teams. The large series of the Massachusetts General Hospital, which included more than 800 cingulotomies over a period of 4 decades, resulted in no deaths and just two intracranial hemorrhages.52,58 Neurological and behavioral outcomes were monitored by the investigators in long-term follow-up. In 1987, Ballantine and collaborators reported on a mixed series of 198 pain and psychiatric patients who had undergone one or more cingulotomies between 1962 and 1982.58 The follow-up period ranged from 2 to 22 years. Thirty-two patients had OCD and 14 had nonobsessive anxiety disorders. Although outcome in the nonobsessive patients was better than that in the OCD patients, 18 of the OCD patients exhibited marked improvement, defined as “not critically ill or institutionalized, usually working to some extent, but still displaying many serious problems or suffering periodic recurrence of disabling symptoms, requiring continuing psychiatric supervision.” A subgroup of 8 patients was functioning well, with or without maintenance of medications or psychotherapy. A subsequent study from the same group assessed the outcomes of cingulotomy in this OCD cohort via mailed questionnaires and interviews aimed at quantifying the severity of the illness.59 Four patients had committed suicide since the surgery. The authors estimated, conservatively, that 25% to 30% of patients had shown substantial improvement after one or more cingulotomy operations. Since then, patients undergoing cingulotomy for OCD have been monitored prospectively, with symptom severity assessed with the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (YBOCS) and other validated rating scales.60 At last assessment, 14 patients (32%) with a mean follow-up period of 32 months had met the criteria for a clinical response that was not attributable to other treatments and provided subjective evidence of at least moderate improvement in anxiety and depression.60

Capsulotomy

Stereotactic capsulotomy for psychiatric disorders was pioneered by Tailarach and by Leksell.61–63 They selected this target because it contains connections between the orbitofrontal cortex and the thalamus, the importance of which to behavior and psychiatric illness became evident from studies correlating lesion location and outcome after open leukotomy.64 Meyer and Beck carefully analyzed pathologic material obtained from patients who had undergone open leukotomy.65 They observed that good clinical results were associated with lesions that included the anterior limb of the internal capsule. Stereotactic ablation of these areas (capsulotomy) was developed as a safer alternative to open operations. During its early investigation, capsulotomy was attempted in patients with diagnoses ranging from schizophrenia to depression.66 Later work was focused on patients with anxiety disorders and OCD because of encouraging results observed in this population.64

Anterior capsulotomies have been performed successfully with two techniques: stereotactic thermal radiofrequency ablation and the newer technique of radiosurgical Gamma Knife ablation.67 A controlled trial of Gamma Knife ventral capsulotomy, under way at the time of this writing,68 will help clarify whether the efficacy and safety outcomes of thermocapsulotomy (which typically entails larger lesion volumes) are similar to those achieved with the more focal and more inferior target of gamma ventral capsulotomy.69 Radiofrequency ablation is similar to ablative procedures for movement disorders (aside from the target). Bilateral bur holes are created at the level of the coronal suture, and 1.5-mm-diameter electrodes with 10-mm uninsulated tips are stereotactically inserted into the targeted area. The radiofrequency lesions are created by heating the probe tip to 75°C for 75 seconds. Two partially overlapping lesions are made on each side to create a final lesion 15 to 18 mm in height.57,70 In a retrospective analysis, Lippitz and associates at the Karolinska Institute suggested that lesions located in the middle third of the anterior limb of the internal capsule, 4 mm dorsal to the plane of the foramen of Monro, are associated with good outcomes.67,71 The topography of the lesion was more important on the right side, thus suggesting greater relevance to interruption of the CSPTC system on the right side for affecting OCD symptoms. This study has a significant limitation, however, in that determination of lesion location was not made by raters blind to patient outcomes. In general, the relevance of laterality to therapeutic improvement in OCD remains to be clarified. Furthermore, in terms of location, early in the development of gamma ventral capsulotomy, single Gamma Knife “shots” with 4-mm collimators restricted to the middle third of the capsule proved ineffective. The addition of lesions in the ventral third of the capsule that impinged on the adjacent ventral striatum appeared to be necessary for therapeutic benefit.72

Capsulotomy has been studied in relatively large series of patients with refractory, severe OCD. Herner in 1961 reported the results of capsulotomy in a series of 116 patients with various disorders.66 Approximately 70% of the patients with obsessive symptoms showed satisfactory improvement. Recent publications using modern, standardized OCD severity scales have confirmed the efficacy of gamma capsulotomy and thermocapsulotomy in the management of severe OCD. The proportion of patients achieving a reduction in their YBOCS score of at least 35% has been reported to be 53%73 and 57%.74 Previous studies used different scales to quantify outcomes. Lippitz and coauthors reported that in 29 patients undergoing capsulotomy, 16 (55%) had a 50% or greater improvement in symptoms.67 Mindus and Meyerson monitored 22 OCD patients for an average of 8 years who underwent capsulotomy and reported that 15 patients (68%), including some who underwent two operations, had a 50% or greater improvement in symptoms.70

Even though the perioperative safety of stereotactic radiofrequency thermolesioning procedures has been demonstrated,57,75,76 concerns remain regarding possible long-term adverse effects after gamma capsulotomy. These concerns have been addressed by one study in which it was demonstrated that in patients observed at a mean of 17 years after procedures using doses of 120 to 170 Gy, small lesions were identified in the desired topography with no late adverse effects such as neoplasia or hemorrhagic infarctions.77 The peak volume of the necrotic lesions after gamma capsulotomy has previously been reported to occur at 6 to 9 months.78 Radiosurgical edema, which is delayed in onset after surgery, can take longer to resolve. Very delayed cyst formation has been reported in 1.6% to 3.6% of patients undergoing Gamma Knife radiosurgery for arteriovenous malformations.79 The incidence of this adverse effect after gamma ventral capsulotomy remains to be clarified.

Having defined the procedural safety of gamma and thermolesional capsulotomy, one must also consider the long-term neurocognitive effects of creating these lesions. Initial studies suggested that capsulotomy posed a low risk for adverse long-term effects on cognition or personality57,80–82; however, more recent reports indicate that the risk to cognitive function may be higher than previously thought.63 Studying a population of 26 patients with various, typically non-OCD anxiety disorders, Ruck and associates found that capsulotomy alleviated severe symptoms but that 7 patients suffered from significant apathy and decline in executive function on retrospective examination.63 The risk for neurocognitive complications and frontal lobe dysfunction was confirmed in a subsequent study.83 The elevated neurocognitive risk associated with capsulotomy was verified in the OCD population by the same group of investigators, who reported data from 25 OCD patients monitored for a mean of 10.9 years after intervention.75 Again, thermocapsulotomy and gamma capsulotomy were found to effectively alleviate OCD symptoms, but 10 patients experienced apathy and significant deterioration in executive function. The authors suggested that smaller lesions with less medial and posterior extension, particularly in the right hemisphere, were less prone to these adverse effects. It is also important to note that apathy and executive dysfunction were overwhelmingly seen in patients who underwent repeated procedures or Gamma Knife lesions at higher radiation doses than those that would now be used.

Subcaudate Tractotomy and Limbic Leukotomy

Subcaudate tractotomy was developed by Knight84–86 based on the results of “restricted orbital undercutting operations” that were performed in the 1950s and 1960s as a more selective alternative to open leukotomy. The stereotactic method for subcaudate tractotomy was developed to focally ablate the substantia innominata ventral to the head of the caudate nucleus, the region to which the investigators had attributed the best therapeutic effects of these previous operations. Although the original ablative intent was aimed at the fibers connecting the frontal cortex to the hypothalamus or amygdala, it is more likely that the behavioral improvements were related to disruption of the reciprocal connections between the orbitofrontal cortex and thalamus.87 The initial procedure consisted of implanting radioactive seeds within the target area via a basal frontal stereotactic approach. Although early results seemed to be best in patients with intractable depression,85 positive results were also noted in a smaller subset of patients with OCD. A subsequent series of 208 patients included follow-up of 18 patients with obsessional neurosis, 50% of whom experienced good results.88 A later series showed more conservative results, with approximately 35% of patients demonstrating a good response 1 year after surgery.89

Limbic leukotomy combines stereotactic cingulotomy and subcaudate tractotomy.90 This procedure has been reported to be more effective than subcaudate tractotomy alone in managing intractable OCD, with good results reported in up to 89% of patients.53,91 Perhaps because of the improvements shown in several relatively large patient series, limbic leukotomy and subcaudate tractotomy have recently re-emerged as a focus of interest for intractable OCD or major depression.92–95

Deep Brain Stimulation

To minimize the risks associated with psychiatric neurosurgical procedures, DBS, an intervention that can be adjusted or discontinued, has been explored as an alternative to neuroablation. In the past decade, DBS has supplanted lesioning for the treatment of movement disorders. Studies comparing thalamic DBS with thalamotomy suggest that the two interventions comparably suppress tremor but that DBS may have a better safety profile.96–98 More than 55,000 DBS devices have been implanted worldwide over the past 20 years, thus establishing a long-term safety and efficacy track record for the treatment of movement disorders. Nuttin and colleagues were the first group to use DBS for OCD; they targeted the tissues traditionally targeted by capsulotomy.99 Their initial success led to subsequent multicenter studies,100,101 which further demonstrated the safety and efficacy of DBS in patients with intractable and severe OCD. Over time, the VC/VS target for DBS in patients with OCD has been adjusted to a more posterior location than the traditional capsulotomy target originally used by Nuttin. This posterior move resulted from previous experience suggesting that more posteriorly positioned DBS leads were associated with better clinical results.100,102 Moreover, the fibers of the cortical-striatal-thalamic-cortical networks become more compact as they course posteriorly in this region. Translational research on the anatomy and functional connectivity of this DBS target has recently been initiated to clarify the neural network central to the effects of stimulation in this region. In this research, the adjustability of DBS can represent a major technical advantage over lesioning.

The Team

Managing patients with severe refractory OCD can be very challenging. Therefore, a close interdisciplinary team management approach is crucial to the success of a psychiatric neurosurgery program.72 The team should include members from psychiatry, psychology, neuropsychology, neurosurgery, ethics, and allied health fields. Strict inclusion and exclusion criteria should be established, and patients must be monitored and managed by the psychiatry team, which takes charge not only of patient selection but also of programming the DBS device, adjusting medications, continuing behavioral therapy, and monitoring progress.

Patient Selection for Deep Brain Stimulation

Patients with OCD may be candidates for neurosurgical intervention if all reasonable attempts at medical and psychotherapeutic management, including exposure/response prevention therapy, have failed to control the symptoms adequately. Residential treatment at specialized OCD treatment centers (such as the OCD Institute at McLean Hospital or the Rogers Memorial Hospital program), although not typically included in formal entry criteria, is highly desirable. Inclusion criteria differ slightly at various centers, but patients should be significantly disabled by their symptoms. An exhaustive psychiatric diagnostic evaluation is necessary to determine whether OCD is in fact the primary problem and to clarify whether other psychiatric disorders and personality features that may be strong relative contraindications to surgery are present. These, as well as the patient’s psychosocial circumstances more generally, must be carefully evaluated. All these factors influence the likelihood that a given patient will be able to engage in the close follow-up required essentially indefinitely for successful DBS. Symptom severity in OCD is measured with the YBOCS after the YBOCS Symptom Checklist has been administered and reviewed to identify the OCD symptoms that exist and are causing the greatest suffering and functional impairment. Severe OCD is indicated by a score of 28 or greater on the 40-point scale.103 The Humanitarian Device Exemption for DBS as a means of treating OCD recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) mandates a minimal YBOCS severity score of 30. Lack of response to multiple medications, including adequate (often high) doses of serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI) or SSRIs for a minimum of 3 months for each medication, must be documented. Although positive controlled data on the role of medication “augmentation” (i.e., combinations) in OCD remain relatively rare, attempts combining an antipsychotic medication with a concurrent SRI appear to be justified, and benzodiazepine augmentation (e.g., with clonazepam) is often used in an attempt to treat severe OCD-related and non–OCD-related anxiety, which frequently co-occur in this population. The vast majority of patients who undergo evaluation will be on chronic psychotropic medication regimens. Even if judged to have been of minimal benefit for “core” OCD symptoms, such regimens are often continued for comorbid conditions. DBS (or an ablative procedure) will thus represent an attempt to augment the effects of medications, as well as the OCD-specific behavior therapy described later.

Exclusion criteria have varied to some degree among neurosurgical studies of OCD. All have excluded those for whom surgery is contraindicated because of neurological illness. The more difficult decision is when to exclude a patient for psychiatric reasons. This decision primarily involves a judgment whether a patient will be able to cooperate with the surgical procedure and especially with the rather extensive follow-up requirements. Current or unstably remitted substance abuse or dependence or a severe personality disorder makes it less likely that an individual will be able to comply with this type of treatment.72 Active suicidal impulses, suicide plans, and self-injurious behavior may also seriously compromise adherence to stimulation treatment. It is important to probe diligently (using multiple informants) during patient evaluation to assess the possibility that a patient might have an unexpressed plan for suicide if the surgical intervention fails to meet the patient’s private criterion for success. For example, chronically disabled patients may view their inability to regain independent living status and employment by a certain deadline as evidence of failure, thus prompting self-injury or suicide attempts. Clinical observations suggest that this can occur even when the OCD symptoms improve.104

It is not clear at this time whether certain symptom subtypes within the heterogeneous categorical diagnosis of OCD may have a worse prognosis after neurosurgical intervention. However, certain factors might negatively affect the prognosis with medications and behavior therapies. For example, patients with OCD exclusively focused on compulsive hoarding have been reported to respond more poorly to conventional psychiatric treatments in some studies,105 although others find that multimodal treatment can be effective.46 It is likewise not clear whether body dysmorphic disorders comorbid with OCD tend to be a negative prognostic indicator, as seemed to be the case in some studies.101 Also somewhat unclear is whether patients who are not convinced that their symptoms are based on illness (poor-insight type) may be poor surgical candidates. For example, a subset of patients with poor insight have a deteriorative course, but this appeared to be due to the presence of co-occurring schizophrenia-spectrum disorders and was not true of individuals whose only psychotic symptom was complete conviction and lack of insight about their obsessions.106 Poor insight has been found to be associated with other clinical features that might themselves have prognostic significance, such as somatic and hoarding-saving obsessions and alexithymia.107 Patients with clear nonaffective and non-OCD psychotic symptoms have been excluded on the basis of previous literature suggesting that primary psychotic illnesses respond poorly to neurosurgery.72 Those with a history of mania should also be excluded from consideration for DBS at present because of the risk for stimulation-induced mania.

Informed Consent

A well-designed informed consent process is essential to the contemporary study of neurosurgical procedures for psychiatric disorders. Recent studies of lesioning procedures and DBS have required direct consent of the patient and have not included individuals who are unable to provide this for themselves. Mental illness does not, by itself, make an individual incompetent. In fact, many patients with psychiatric disease are extremely well informed about their illness and the various treatments available, so the surgical consent process may be conducted as for any other disorder. Nevertheless, there are ethical concerns tied to neurosurgical procedures for psychiatric disease that merit special attention.108 Guidelines for the informed consent process have been established by an international working group of physicians and ethicists. Representative inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in articles by Greenberg and associates.100,101 At a number of centers, interviews of patients by formal consent monitors are included as part of the evaluation process, and a report by a monitor is provided to an independent review committee that evaluates candidacy for surgery on the basis of the clinical findings and treatment history.

Stereotactic Surgical Procedure

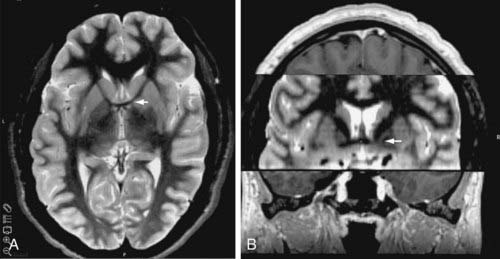

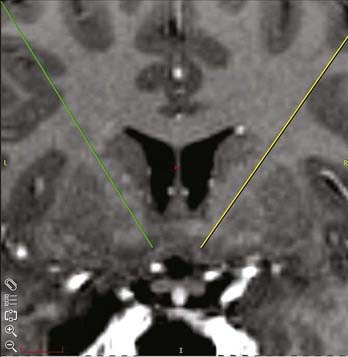

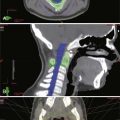

A standard frame-based stereotactic procedure can be used in the same fashion as for movement disorders.54,109 The VC/VS target can be visualized on coronal and axial volumetric and T2-weighted MRI (Fig. 88-2). The anatomic target lies approximately 4 to 9 mm from the midline, 0 to 5 mm anterior to the posterior border of the anterior commissure, and 1 to 4 mm below the intercommissural plane. These x, y, and z stereotactic coordinates must be visualized directly on MRI to ensure that the target rests at the ventral aspect of the anterior limb of the internal capsule abutting the more ventrally located ventral striatal region. Surgical plans can be created preoperatively on reformatted volumetric MRI and computed tomography (CT) scans. The standard entry point lies anterior to the coronal suture at a point at which a mediolateral trajectory has been established along the long axis of the anterior limb of the internal capsule (Fig. 88-3). The trajectory should avoid the ventricles, the sulci, and cortical vessels. Commercially available stereotactic planning systems facilitate the planning process.

A new DBS lead was created for the VC/VS target (Model 3391, Medtronic, Inc., Minneapolis, MN). The lead, which was designed to span the dorsoventral extent of the anterior internal capsule, has four cylindrical electrode contacts that are 1.3 mm in diameter and 3 mm in length, with 4 mm of insulated wire between the contacts. This lead configuration was based on that of the Pices Quad Compact device first used for OCD at the capsulotomy target by Nuttin and colleagues in Belgium. This lead was chosen to allow stimulation throughout the dorsal-ventral extent of the anterior limb of the interval capsule in the coronal plane. As of this writing, a multicenter National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)-supported controlled trial of DBS for OCD is using another Medtronic lead (Model 3387) that has four 1.5-mm-long contacts each separated by 1.5 mm. The rationale for this variation is to stimulate the territory of the VC/VS that spans the ventral-most anterior capsule and the dorsal-most portion of the ventral striatum, where stimulation has appeared to be most effective in open studies.100

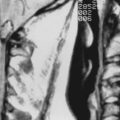

After the lead is inserted within the VC/VS target, intraoperative test stimulation is performed with the patient awake. Stimulation through each of the four contacts is tested with various stimulation parameters, including frequencies of 100 to 130 Hz, pulse widths of at least 90 µsec, and amplitudes greater than 1 V. During test stimulation the patient is evaluated for changes in anxiety, mood, and energy levels, as well as paresthesias, muscle contractions, alterations in vital signs, and other potential adverse effects. It has become the practice of experienced centers to have intraoperative testing performed by the team psychiatrist, who will also be responsible for subsequent programming. After securing the lead at the level of the skull, the remainder of the DBS system is implanted as for movement disorders. CT or MRI, or both, is performed postoperatively to determine the location of the implanted leads and to assess for intracranial air and hemorrhage. Additionally, skull and chest radiographs can be obtained to view the position of the electrodes, connecting wires, and pulse generators (Fig. 88-4).

FIGURE 88-4 Postoperative anteroposterior skull radiograph after bilateral implantation of deep brain stimulation (DBS) electrodes in the region of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum. Note that the entry points (bur hole) for the DBS leads are more lateral than usually preferred for targeting the thalamus or subthalamic nucleus in movement disorders. The entry point is selected more laterally so that the trajectory of implantation follows the angle of the anterior limb of the internal capsule, as shown in Figure 88-3. It is also possible to note the lead’s four contacts, longer and separated by a greater distance than the standard DBS electrodes used for movement disorder surgery.

Outcomes of Deep Brain Stimulation

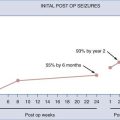

The combined experience of collaborating centers that have performed DBS similarly over the past decade and used this multidisciplinary approach for OCD has been published previously.100,101 Patients with severe, disabling, and treatment-refractory OCD were enrolled in open-label studies. Strict inclusion and exclusion criteria were followed, and patients were managed by multidisciplinary teams that included psychiatrists, neurosurgeons, neuropsychologists, and independent case review after ethics committee approval. After implantation and programming of the DBS device, patients underwent close clinical monitoring on a weekly to monthly basis, depending on their clinical course. Outcomes were assessed with a variety of standardized scales, including the YBOCS, global assessment of functioning (GAF), Hamilton Anxiety and Depression Rating Scales (HAM-A and HAM-D, respectively), and others. A battery of neuropsychological tests were administered at baseline and after 6 months of continuous DBS.

Complications of Deep Brain Stimulation for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Complications of DBS surgery are categorized as surgical, device related, and stimulation related. Surgical complications included two patients with small intracerebral hemorrhages, one of which was asymptomatic and the other resulted in transient apathy. There were no permanent neurological deficits in these patients. One patient suffered an isolated seizure after lead implantation, and a superficial wound infection that was treated successfully with antibiotics developed in another patient. Two patients experienced hardware failure that required replacement of either the DBS lead or extension wire but suffered no further adverse effects. Stimulation-related complications have included rapid recurrence of depression, including suicidality, when stimulation was interrupted by battery depletion or electromagnetic interference. Conversely, marked insomnia associated with hypomania was observed on initiation or resumption of DBS after replacement of the stimulator.100 Although none of these events resulted in lasting sequelae, they all required rapid intervention by the programming psychiatrist and, when needed, by the team neurosurgeon.

Summary of Deep Brain Stimulation

Thus far, studies of VC/VS DBS for OCD suggest that the intervention has an acceptable safety profile, although only tentative conclusions can be drawn about safety from the small-scale studies published to date. It also appears, largely on the basis of open-label studies, to have therapeutic potential in individuals with otherwise treatment-resistant OCD. The beneficial effects of DBS on core OCD symptoms, nonspecific anxiety, depression, and functioning appear robust and, to varying degrees, progressive on a group basis. As a result of these clinical studies, the U.S. FDA recently issued a Humanitarian Device Exemption for the use of VC/VS DBS in treating OCD. More definitive evidence regarding the therapeutic benefits of VC/VS DBS are expected from an NIMH-supported controlled trial of this therapy that has recently enrolled its first patients. Although the etiology of OCD remains to be clarified, two small neuroimaging studies have found that acute or chronic DBS at the VC/VS target modulates nodes within the neurocircuitry hypothesized to underlie the pathophysiology of OCD.110,111 Neuroimaging and translational research are expected to contribute substantially to our understanding of the mechanisms of action of DBS at this target in patients with OCD, as well as contribute to improved patient selection.

Ballantine HTJr, Bouckoms AJ, Thomas EK, et al. Treatment of psychiatric illness by stereotactic cingulotomy. Biol Psychiatry. 1987;22:807.

Ballantine HTJr, Cassidy WL, Flanagan NB, et al. Stereotaxic anterior cingulotomy for neuropsychiatric illness and intractable pain. J Neurosurg. 1967;26:488.

Breiter HC, Rauch SL, Kwong KK, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of symptom provocation in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:595.

Cartwright C, Hollander E. SSRIs in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Depress Anxiety. 1998;8(suppl 1):105.

Cassidy WL, Ballantine HTJr, Flanagan NB. Frontal cingulotomy for affective disorders. Recent Adv Biol Psychiatry. 1965;8:269.

Cho DY, Lee WY, Chen CC. Limbic leukotomy for intractable major affective disorders: a 7-year follow-up study using nine comprehensive psychiatric test evaluations. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15:138.

Dougherty DD, Baer L, Cosgrove GR, et al. Prospective long-term follow-up of 44 patients who received cingulotomy for treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:269.

Fulton F. The Frontal Lobes and Human Behavior. Springfield IL: Charles C Thomas; 1952.

Greenberg BD, Gabriels LA, Malone DAJr, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral internal capsule/ventral striatum for obsessive-compulsive disorder: worldwide experience. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:64.

Haber SN, Fudge JL, McFarland NR. Striatonigrostriatal pathways in primates form an ascending spiral from the shell to the dorsolateral striatum. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2369.

Heimer L. The legacy of the silver methods and the new anatomy of the basal forebrain: implications for neuropsychiatry and drug abuse. Scand J Psychol. 2003;44:189.

Herner T. Treatment of mental disorders with frontal stereotaxic thermolesions. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1961;36:36.

Kelly D, Richardson A, Mitchell-Heggs N. Stereotactic limbic leucotomy: neurophysiological aspects and operative technique. Br J Psychiatry. 1973;123:133.

Kihlstrom L, Guo WY, Lindquist C, et al. Radiobiology of radiosurgery for refractory anxiety disorders. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:294.

Knight G. Stereotactic tractotomy in the surgical treatment of mental illness. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1965;28:304.

Lippitz BE, Mindus P, Meyerson BA, et al. Lesion topography and outcome after thermocapsulotomy or gamma knife capsulotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: relevance of the right hemisphere. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:452.

Maclean PD. Some psychiatric implications of physiological studies on frontotemporal portion of limbic system (visceral brain). Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1952;4:407.

Mitchell-Heggs N, Kelly D, Richardson A. Stereotactic limbic leucotomy—a follow-up at 16 months. Br J Psychiatry. 1976;128:226.

Moniz E. Prefrontal leucotomy in the treatment of mental disorders. 1937. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:236.

Papez JW. A proposed mechanism for emotion. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1937;38:725.

Shields DC, Asaad W, Eskandar EN, et al. Prospective assessment of stereotactic ablative surgery for intractable major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:449.

Sidibe M, Bevan MD, Bolam JP, et al. Efferent connections of the internal globus pallidus in the squirrel monkey: I. Topography and synaptic organization of the pallidothalamic projection. J Comp Neurol. 1997;382:323.

1 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Arlington VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

2 Narrow WE, Rae DS, Robins LN, et al. Revised prevalence estimates of mental disorders in the United States: using a clinical significance criterion to reconcile 2 surveys’ estimates. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:115.

3 Eisen JL, Mancebo MA, Pinto A, et al. Impact of obsessive-compulsive disorder on quality of life. Compr Psychiatry. 2006;47:270.

4 Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349:1436.

5 Pallanti S, Hollander E, Bienstock C, et al. Treatment non-response in OCD: methodological issues and operational definitions. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;5:181.

6 Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, Kozak MJ, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of exposure and ritual prevention, clomipramine, and their combination in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:151.

7 Brody AL, Saxena S, Schwartz JM, et al. FDG-PET predictors of response to behavioral therapy and pharmacotherapy in obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 1998;84:1.

8 Baxter LRJr, Saxena S, Brody AL, et al. Brain mediation of obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms: evidence from functional brain imaging studies in the human and nonhuman primate. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 1996;1:32.

9 Cartwright C, Hollander E. SSRIs in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Depress Anxiety. 1998;8(suppl 1):105.

10 Hollander E, Bienstock CA, Koran LM, et al. Refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: state-of-the-art treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(suppl 6):20.

11 Rasmussen SA, Eisen JL. The epidemiology and clinical features of obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1992;15:743.

12 Finger S. The era of cortical localization. In: Finger S, editor. Origins of Neuroscience. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994:32-50.

13 Harlow JM. Passage of an iron rod through the head. Boston Med Surg J. 1948;39:389.

14 Ratiu P, Talos IF, Haker S, et al. The tale of Phineas Gage, digitally remastered. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:637.

15 Harlow J. Recovery from the passage of an iron bar through the head. Publications of the Massachusetts Medical Society. 1868;2:327.

16 Harlow JM. Passage of an iron rod through the head. 1848. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999;11:281.

17 Finger S. Sleep and emotion. In: Finger S, editor. Origins of Neuroscience. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994:280-296.

18 Jacobsen C, Wolf J, Jackson T. An experimental analysis of the functions of the frontal association areas in primates. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1935;82:1.

19 Moniz E. Prefrontal leucotomy in the treatment of mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1937;93:1379.

20 Moniz E. Prefrontal leucotomy in the treatment of mental disorders. 1937. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:236.

21 Gabriels L, Nuttin B, Cosyns P. Applicants for stereotactic neurosurgery for psychiatric disorders: role of the Flemish advisory board. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;117:381.

22 Mashour GA, Walker EE, Martuza RL. Psychosurgery: past, present, and future. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;48:409.

23 Papez JW. A proposed mechanism for emotion. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1937;38:725.

24 Papez JW. A proposed mechanism of emotion. 1937. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1995;7:103.

25 Maclean PD. Some psychiatric implications of physiological studies on frontotemporal portion of limbic system (visceral brain). Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1952;4:407.

26 Maclean PD. The limbic system (“visceral brain”) and emotional behavior. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1955;73:130.

27 Cassidy WL, Ballantine HTJr, Flanagan NB. Frontal cingulotomy for affective disorders. Recent Adv Biol Psychiatry. 1965;8:269.

28 Ballantine HTJr, Cassidy WL, Flanagan NB, et al. Stereotaxic anterior cingulotomy for neuropsychiatric illness and intractable pain. J Neurosurg. 1967;26:488.

29 Alexander GE, DeLong MR, Strick PL. Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1986;9:357.

30 Heimer L. The legacy of the silver methods and the new anatomy of the basal forebrain: implications for neuropsychiatry and drug abuse. Scand J Psychol. 2003;44:189.

31 Heimer L. A new anatomical framework for neuropsychiatric disorders and drug abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1726.

32 de Olmos JS, Heimer L. The concepts of the ventral striatopallidal system and extended amygdala. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;877:1.

33 Haber SN, Gdowski MJ. The basal ganglia. In: Paxinos G, Mai J, editors. The Human Nervous System. Philadelphia: Academic Press, 2003.

34 Baron MS, Sidibe M, DeLong MR, et al. Course of motor and associative pallidothalamic projections in monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 2001;429:490.

35 Parent A, Hazrati LN. Functional anatomy of the basal ganglia. II. The place of subthalamic nucleus and external pallidum in basal ganglia circuitry. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1995;20:128.

36 Shink E, Sidibe M, Smith Y. Efferent connections of the internal globus pallidus in the squirrel monkey: II. Topography and synaptic organization of pallidal efferents to the pedunculopontine nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 1997;382:348.

37 Sidibe M, Bevan MD, Bolam JP, et al. Efferent connections of the internal globus pallidus in the squirrel monkey: I. Topography and synaptic organization of the pallidothalamic projection. J Comp Neurol. 1997;382:323.

38 Haber SN, Fudge JL, McFarland NR. Striatonigrostriatal pathways in primates form an ascending spiral from the shell to the dorsolateral striatum. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2369.

39 Modell JG, Mountz JM, Curtis GC, et al. Neurophysiologic dysfunction in basal ganglia/limbic striatal and thalamocortical circuits as a pathogenetic mechanism of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1989;1:27.

40 Baxter LRJr, Phelps ME, Mazziotta JC, et al. Local cerebral glucose metabolic rates in obsessive-compulsive disorder. A comparison with rates in unipolar depression and in normal controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:211.

41 Schwartz JM, Stoessel PW, Baxter LRJr, et al. Systematic changes in cerebral glucose metabolic rate after successful behavior modification treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:109.

42 Breiter HC, Rauch SL. Functional MRI and the study of OCD: from symptom provocation to cognitive-behavioral probes of cortico-striatal systems and the amygdala. Neuroimage. 1996;4:S127.

43 Breiter HC, Rauch SL, Kwong KK, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of symptom provocation in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:595.

44 Rauch SL, Wedig MM, Wright CI, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging study of regional brain activation during implicit sequence learning in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:330.

45 Adler CM, McDonough-Ryan P, Sax KW, et al. fMRI of neuronal activation with symptom provocation in unmedicated patients with obsessive compulsive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2000;34:317.

46 Saxena S, Brody AL, Maidment KM, et al. Cerebral glucose metabolism in obsessive-compulsive hoarding. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1038.

47 Mataix-Cols D, Wooderson S, Lawrence N, et al. Distinct neural correlates of washing, checking, and hoarding symptom dimensions in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:564.

48 Baker KB, Kopell BH, Malone D, et al. Deep brain stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder: using functional magnetic resonance imaging and electrophysiological techniques: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:E367.

49 Fulton F. The surgical approach to mental disorder. McGill Med J. 1948;17:133.

50 Fulton F. The Frontal Lobes and Human Behavior. Springfield IL: Charles C Thomas; 1952.

51 Kopell BH, Machado AG, Rezai AR. Not your father’s lobotomy: psychiatric surgery revisited. Clin Neurosurg. 2005;52:315.

52 Cosgrove GR, Rauch SL. Stereotactic cingulotomy. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2003;14:225.

53 Marino Júnior R, Cosgrove GR. Neurosurgical treatment of neuropsychiatric illness. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1997;20:933.

54 Machado A, Rezai AR, Kopell BH, et al. Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease: surgical technique and perioperative management. Mov Disord. 2006;21:S247.

55 Zonenshayn M, Rezai AR, Mogilner AY, et al. Comparison of anatomic and neurophysiological methods for subthalamic nucleus targeting. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:282.

56 Spangler WJ, Cosgrove GR, Ballantine HTJr, et al. Magnetic resonance image–guided stereotactic cingulotomy for intractable psychiatric disease. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:1071.

57 Mindus Jenike MA. Neurosurgical treatment of malignant obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1992;15:921.

58 Ballantine HTJr, Bouckoms AJ, Thomas EK, et al. Treatment of psychiatric illness by stereotactic cingulotomy. Biol Psychiatry. 1987;22:807.

59 Jenike MA, Baer L, Ballantine T, et al. Cingulotomy for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. A long-term follow-up of 33 patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:548.

60 Dougherty DD, Baer L, Cosgrove GR, et al. Prospective long-term follow-up of 44 patients who received cingulotomy for treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:269.

61 Talairach J, Hecaen H, David M. Lobotomies prefrontal limitee par electrocoagulation des fibres thalamo-frontales a leur emergence du bras anterieur de la capsule interne. Presented at the Proceedings IV Congres Neurologique International Paris, 1949.

62 Leksell L, Backlund EO. [Radiosurgical capsulotomy—a closed surgical method for psychiatric surgery.]. Lakartidningen. 1978;75:546.

63 Ruck C, Andreewitch S, Flyckt K, et al. Capsulotomy for refractory anxiety disorders: long-term follow-up of 26 patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:513.

64 Bingley T, Leksell L, Meyerson BA, et al. Stereotactic anterior capsulotomy in anxiety and obsessive-compulsive states. In: Livingston Laitinen, editor. Surgical Approaches in Psychiatry. Lancaster: Medical and Technical Publishing; 1973:159.

65 Meyer A, Beck E. Prefrontal Leucotomy and Related Operations. London: Oliver & Boyd; 1954.

66 Herner T. Treatment of mental disorders with frontal stereotaxic thermolesions. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1961;36:36.

67 Lippitz BE, Mindus P, Meyerson BA, et al. Lesion topography and outcome after thermocapsulotomy or gamma knife capsulotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: relevance of the right hemisphere. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:452.

68 Lopes AC, Greenberg BD, Norén G, et al. Treatment of resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder with ventral capsular/ventral striatal gamma capsulotomy: a pilot prospective study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;21:393.

69 Cecconi JP, Lopes AC, Duran FL, et al. Gamma ventral capsulotomy for treatment of resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a structural MRI pilot prospective study. Neurosci Lett. 2008;447:138.

70 Mindus P, Meyerson B. Anterior capsulotomy for intractable anxiety disorders, 3rd ed. Schmidek H, Sweeney JA, editors. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques, vol. 2. Philadelphia: WB Saunders. 1982.

71 Lippitz B, Mindus P, Meyerson BA, et al. Obsessive compulsive disorder and the right hemisphere: topographic analysis of lesions after anterior capsulotomy performed with thermocoagulation. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1997;68:61.

72 Greenberg BD, Price LH, Rauch SL, et al. Neurosurgery for intractable obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression: critical issues. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2003;14:199.

73 Oliver B, Gascon J, Aparicio A, et al. Bilateral anterior capsulotomy for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorders. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2003;81:90.

74 Liu K, Zhang H, Liu C, et al. Stereotactic treatment of refractory obsessive compulsive disorder by bilateral capsulotomy with 3 years follow-up. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15:622.

75 Ruck C, Karlsson A, Steele JD, et al. Capsulotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: long-term follow-up of 25 patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:914.

76 Mindus P. Present-day indications for capsulotomy. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1993;58:29.

77 Kihlstrom L, Hindmarsh T, Lax I, et al. Radiosurgical lesions in the normal human brain 17 years after gamma knife capsulotomy. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:396.

78 Kihlstrom L, Guo WY, Lindquist C, et al. Radiobiology of radiosurgery for refractory anxiety disorders. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:294.

79 Pan HC, Sheehan J, Stroila M, et al. Late cyst formation following gamma knife surgery of arteriovenous malformations. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(suppl):124.

80 Mindus P, Meyerson BA. Anterior capsulotomy for intractable anxiety disorders, 3rd ed. Schmidek H, Sweet W, editors. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques, vol. 2. Philadelphia: WB Saunders. 1995:1443-1455.

81 Mindus P, Edman G, Andreewitch S. A prospective, long-term study of personality traits in patients with intractable obsessional illness treated by capsulotomy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;99:40.

82 Mindus P, Nyman H, Rosenquist A, et al. Aspects of personality in patients with anxiety disorders undergoing capsulotomy. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1988;44:138.

83 Ruck C, Edman G, Asberg M, et al. Long-term changes in self-reported personality following capsulotomy in anxiety patients. Nord J Psychiatry. 2006;60:486.

84 Knight G. The orbital cortex as an objective in the surgical treatment of mental illness: the results of 450 cases of open operation and the development of the stereotactic approach. Br J Surg. 1964;51:114.

85 Knight G. Stereotactic tractotomy in the surgical treatment of mental illness. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1965;28:304.

86 Knight GC. Bi-frontal stereotactic tractotomy: an atraumatic operation of value in the treatment of intractable psychoneurosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1969;115:257.

87 Martuza RL, Chiocca EA, Jenike MA, et al. Stereotactic radiofrequency thermal cingulotomy for obsessive compulsive disorder. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1990;2:331.

88 Goktepe EO, Young LB, Bridges PK. A further review of the results of stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy. Br J Psychiatry. 1975;126:270.

89 Hodgkiss AD, Malizia AL, Bartlett JR, et al. Outcome after the psychosurgical operation of stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy, 1979-1991. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1995;7:230.

90 Kelly D, Richardson A, Mitchell-Heggs N. Stereotactic limbic leucotomy: neurophysiological aspects and operative technique. Br J Psychiatry. 1973;123:133.

91 Mitchell-Heggs N, Kelly D, Richardson A. Stereotactic limbic leucotomy—a follow-up at 16 months. Br J Psychiatry. 1976;128:226.

92 Cho DY, Lee WY, Chen CC. Limbic leukotomy for intractable major affective disorders: a 7-year follow-up study using nine comprehensive psychiatric test evaluations. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15:138.

93 Kim MC, Lee TK. Stereotactic lesioning for mental illness. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2008;101:39.

94 Shields DC, Asaad W, Eskandar EN, et al. Prospective assessment of stereotactic ablative surgery for intractable major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:449.

95 Woerdeman PA, Willems PW, Noordmans HJ, et al. Frameless stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy for intractable obsessive-compulsive disorder. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2006;148:633.

96 Tasker RR. Tremor of parkinsonism and stereotactic thalamotomy. Mayo Clin Proc. 1987;62:736.

97 Lyons KE, Koller WC, Wilkinson SB, et al. Long term safety and efficacy of unilateral deep brain stimulation of the thalamus for parkinsonian tremor. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:682.

98 Schuurman PR, Bosch DA, Bossuyt PM, et al. A comparison of continuous thalamic stimulation and thalamotomy for suppression of severe tremor. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:461.

99 Nuttin B, Cosyns P, Demeulemeester H, et al. Electrical stimulation in anterior limbs of internal capsules in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Lancet. 1999;354:1526.

100 Greenberg BD, Gabriels LA, Malone DAJr, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral internal capsule/ventral striatum for obsessive-compulsive disorder: worldwide experience. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:64.

101 Greenberg BD, Malone DA, Friehs GM, et al. Three-year outcomes in deep brain stimulation for highly resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2384.

102 Nuttin BJ, Gabriels LA, Cosyns PR, et al. Long-term electrical capsular stimulation in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:966.

103 Goodman WK, Price LH. Assessment of severity and change in obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1992;15:861.

104 Abelson JL, Curtis GC, Sagher O, et al. Deep brain stimulation for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:510.

105 Steketee G, Eisen J, Dyck I, et al. Predictors of course in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 1999;89:229.

106 Eisen JL, Rasmussen SA. Obsessive compulsive disorder with psychotic features. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54:373.

107 De Berardis D, Campanella D, Gambi F, et al. Insight and alexithymia in adult outpatients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255:350.

108 Fins JJ. From psychosurgery to neuromodulation and palliation: history’s lessons for the ethical conduct and regulation of neuropsychiatric research. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2003;14:303.

109 Rezai AR, Machado AG, Deogaonkar M, et al. Surgery for movement disorders. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(suppl 2):809.

110 Rauch SL, Dougherty DD, Malone D, et al. A functional neuroimaging investigation of deep brain stimulation in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:558.

111 Van Laere K, Nuttin B, Gabriels L, et al. Metabolic imaging of anterior capsular stimulation in refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a key role for the subgenual anterior cingulate and ventral striatum. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:740.