CHAPTER 28 Suprasellar Meningiomas

INTRODUCTION

The first successful removal of a tuberculum sellae meningioma was performed by Cushing in 1916. Later, in 1929, Cushing and Eisenhardt classified the meningiomas of the tuberculum sellae in four stages, according to their size.1,2 Although Cushing emphasized that the early diagnosis, which determines the surgical results, is based on the attendance and accuracy of ophthalmologists, even in the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) era the history of the symptoms remains too long. However, surgical treatment of these meningiomas evolved significantly over the following decades and in recent series complete removal has been achieved with an acceptable morbidity rate and the mortality is approaching 0%.3–8

The precise definition of SM remains controversial, however. Tumors arising from different locations and extending either primarily or secondarily in the suprasellar area are regarded as such by some authors.3,9–11 Alternatively, taking into account some clinical and therapeutical differences, they are regarded as separate entities according to their exact location, for example, diaphragm sellae, planum sphenoidale, or anterior clinoid meningiomas.5–7,12

SM originate from tuberculum sellae, chiasmatic sulcus, limbus sphenoidale, and partly from diaphragma sellae and extend sub- or retrochiasmatic.6,7 Preoperative differentiation between tuberculum and diaphragma sellae meningiomas might be impossible sometimes and only when tumor attachment to the basal dura is visualized intraoperatively is the exact diagnosis made. Although frontobasal, olfactory tract, planum sphenoidale, anterior clinoid, and medial sphenoid wing meningiomas might extend into the area, they are located prechiasmatically and are not discussed in the current chapter.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

SM represent approximately 5% to 10% of intracranial meningiomas.3–5,8,13,14 They have a typical female preponderance with a female/male ratio of 4 to 4.9:1, and a mean patient age of 50 to 58 years.

NEUROIMAGING

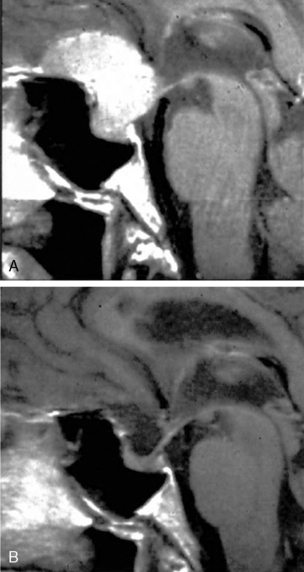

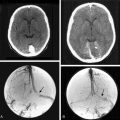

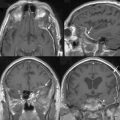

In all patients computed tomography (CT) and MRI, both native and with intravenous administration of a contrast agent, should be made. High-resolution CT scans best reveal the generally hyperostotic bony changes in the region of interest.5,10,12 Meningiomas are usually isointense to brain on T1-weighted MR sequences and hypointense on T2-weighted sequences. They are normally located above the diaphragma sellae, where pituitary gland and stalk can be identified. After administration of intravenous contrast, they enhance homogeneously. In contrast, pituitary macroadenomas tend to demonstrate a higher T2-weighted signal and patchy contrast enhancement. The presence of intrasellar calcifications on CT or of a hyperostosis may suggest meningioma; however, pituitary adenoma or craniopharyngioma sometimes cannot be ruled out. Another important difference is the size of the sella turcica: in the case of SM it is generally not expanded or only slightly enlarged.15

Carotid artery angiography might be performed in patients harboring large tumors and typically shows elevation of one or both A1 segments of the anterior cerebral artery. In a recent study, tumor blush was noted in 70% of the cases and narrowing or lateral displacement of the internal carotid artery was seen in 9.1%.5 Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is used to analyze the location of the carotid artery and anterior cerebral artery complex. If the meningioma extends superiorly toward the floor of the third ventricle behind the anterior cerebral artery complex, complete tumor removal might be more difficult.16

ENDOCRINE TESTING AND OPHTHALMOLOGIC EXAMINATION

Endocrinologic tests for assessment of anterior pituitary function—of the hypothalamopituitary–adrenal, –thyroidal, and –gonadal axes—should be performed before the surgery, then 1 week and 3 months postoperatively. Posterior pituitary function is monitored for at least 1 week postoperatively by measuring fluid intake and urine output, as well as of the specific gravity of the urine. Endocrine deficits, in contrast to pituitary adenomas, are exceptional, but may arise postoperatively, especially if the pituitary has been irritated. In the hands of experience surgeons, these, however, tend to be transient.5

The standard examination should include at least testing the visual acuity for both eyes, Goldmann perimetry, funduscopy, and measuring intraocular pressure.5

SURGICAL TREATMENT

Historically, several approaches to the suprasellar area have been developed and controversy still exists as to the most effective one. Some authors state that the approach should be individually selected according to tumor size and attachment in this area, while others prefer more confined and safe approaches and consider the approach-related morbidity of paramount importance. The approaches that are commonly utilized are the bifrontal,10,12,17 the unifrontal,3,6,11,13 the pterional,5,7,12,13,18 and the frontolateral.3,7,9 In the past few years the extended endoscopic transsphenoidal approach has gained acceptance.

The craniotomy is done generally on the right side unless the tumor has a significantly eccentric extension toward the optic nerve and carotid artery on the left side.5,7,13,19,20 Some surgeons prefer to approach the tumor on the side of worse vision.6 Whatever side is chosen, however, it should be remembered that it is more difficult to remove the tumor portion from underneath the ipsilateral optic nerve. Further, the optic nerve on that side is more prone to surgical lesion.

Bifrontal Approach

The bifrontal approach provides wide exposure of the suprasellar area. The craniotomy should extend anterior as low as possible to the orbital roof. The frontal sinuses are opened and the mucous membranes have to be removed completely. The dura is opened parallel to the base, the sagittal sinus is ligated and cut, and the falx is transected.7 The bifrontal subfrontal exposure provides excellent views of the entire tuberculum sellae, of both optic nerves, as well as internal carotid and anterior cerebral arteries.15,19 However, it has several major drawbacks, including opening the frontal sinus with the related risks of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage and meningitis, bilateral olfactory nerve damage, and bilateral frontal lobes injury.19 Further, due to sectioning of the superior sagittal sinus and draining midline veins, the risk of postoperative brain edema and venous brain infarction is high. For this reasons, we do not recommend the bifrontal approach for resection of SM.7 Some authors use this approach to reach the tumor via the anterior interhemispheric space.

Unilateral Subfrontal Approach

The unilateral subfrontal approach3,6,11,13 includes a basal unilateral craniotomy extended medially to the midline. It provides relatively wide access to the suprasellar area and is less traumatic than the bifrontal approach. Some authors find it superior to frontotemporal approach because it provides wide exposure to both internal carotid arteries and optic nerves. In large tumors, Ciric and colleagues16 proposed that the unilateral craniotomy should be extended across the midline, thus allowing for sectioning of the falx.

Frontotemporal Approach

Frontotemporal (pterional) craniotomy exposes the frontal and temporal lobes, as well as the sylvian fissure and the sphenoid ridge. The removal of lesser sphenoid wing to the superior orbital fissure allows minimizing brain retraction.7 Although some authors recommend wide opening of the sylvian fissure across the limen insulae with release of CSF, we think that it should not be routinely opened, especially in the treatment of smaller tumors.5 The pterional approach allows early CSF release and offers a short route to the lesion. It provides a more advantageous angle between the carotid artery and the optic nerve, as well as access to the back of the tumor.20,21

To achieve better visual outcome, Matthiesen and colleagues20 proposed a modified pterional approach with early optic nerve decompression. The optic canal and nerve, as well as the anterior clinoid process, are unroofed extradurally. The authors find that the release of the optic nerve allows excellent visual outcomes without any deterioration of visual function.

Some skull-base techniques, such as supraorbital osteotomy, removal of the greater and lesser sphenoid wings with opening of the superior orbital fissure, superior orbitotomy to include the supraorbital ridge as a single bone construct, and extradural removal of the anterior clinoid have been introduced to bring the surgeon as close to the tumor as possible and to minimize frontal retraction, thus limiting postoperative neuropsychologic sequelae.15,16,22 Orbitozygomatic osteotomy was introduces to provide further room for additional maneuvering.6,16 However, in case of SM these techniques are required very rarely, if at all.

Frontolateral Approach

The frontolateral approach is a simple and safe procedure that could be regarded as a modification of the frontotemporal approach, including only its frontal part or as a minimally invasive version of the unilateral subfrontal approach. The skin incision is done behind the hair line, starting anterior to the tragus and reaching the midline. The craniotomy should reach the supraorbital notch frontomedially and injury to the supraorbital nerve should be avoided. Laterally a single burr hole is made at the key point. The craniotomy is usually 25 to 35 mm wide and 20 to 25 mm high; however, its extent is modified according to the size of the frontal sinus: opening of the sinus is avoided, unless it is very large.7,21

One recent study compared the outcome after removal of 72 tuberculum sellae meningiomas via 3 different avenues: the bifrontal (in the initial part of the study), the frontotemporal, and the frontolateral.7 Both the morbidity/mortality rates and the visual outcome were found to be related to the approach. The perioperative mortality rate was 9.5% after a bifrontal approach and 0% after frontotemporal and frontolateral approaches. Postoperative brain edema occurred in four patients, all operated via a bifrontal craniotomy. One patient experienced a venous brain infarction and brain edema after bifrontal craniotomy. The rate of visual improvement was significantly higher in patients who underwent frontolateral tumor resection (78%) compared with those who underwent bifrontal craniotomy (46%).

Microsurgical Tumor Removal

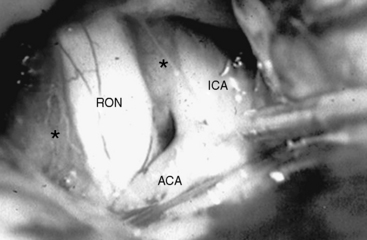

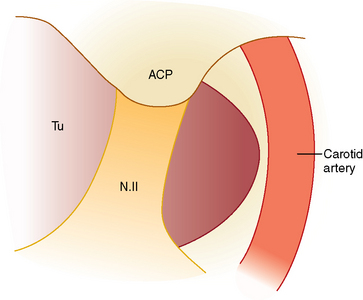

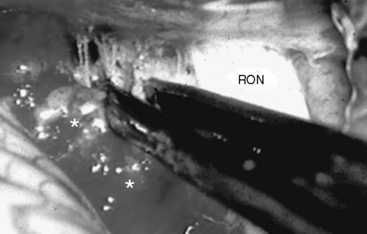

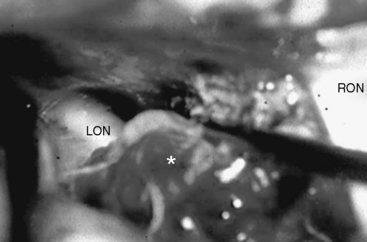

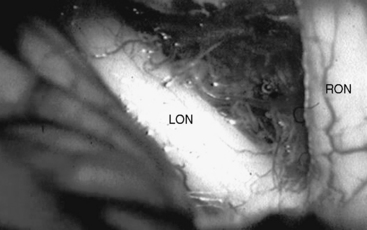

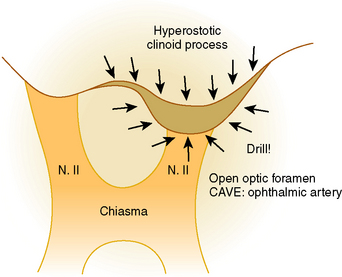

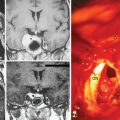

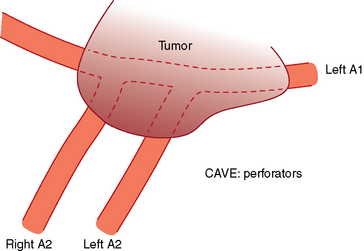

Whatever approach has been selected, the ipsilateral optic nerve and carotid artery need to be identified initially (Figs. 28-1 and 28-2). The tumor matrix is coagulated and the contralateral optic nerve is visualized (Fig. 28-3). In large meningiomas, however, an initial internal debulking is required. Tumor resection is continued and the optic chiasm, the contralateral optic nerve, and carotid artery are identified (Figs. 28-4 and 28-5). With sufficient internal decompression, the tumor can be safely dissected from surrounding structures. The dissection should be performed in the arachnoid plane, thus leaving a protective layer of arachnoid over the optic nerves and chiasm, the anterior communicating artery complex, and the pituitary stalk.16 Special attention needs to be paid to the arterial supply to the optic nerves and chiasm. Their inferior surface is supplied by two or three small arteries, which arise from the medial wall of the internal carotid artery.23 During tumor resection these might be mistaken as tumor feeders and coagulated (Fig. 28-6). The pituitary stalk is generally unilaterally and posteriorly displaced and may be explored behind a layer of arachnoid; it is never encased by the tumor.6 SM might extend into the optic canals under the anterior clinoid process and the optic nerve (Fig. 28-7). In our experience, opening of the optic canal was required in the majority of cases for further tumor removal or exploration.5

FIGURE 28-4 Meningioma encasing the anterior communicating arteries and both anterior cerebral artery.

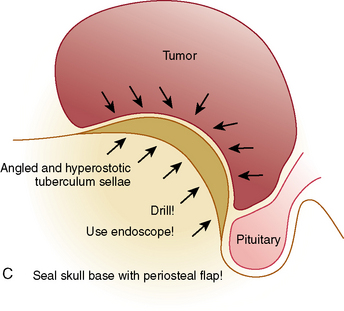

After tumor removal, its matrix is coagulated and the basal dura resected. In case of hyperostosis or bony tumor involvement, they have to be removed with a diamond drill (Fig. 28-8). To avoid CSF leaks some authors propose that the basal attachment of the tumor should be only widely coagulated.6 However, it has been proven that hyperostosis at the tumor base usually represents intraosseous tumor, and the importance of radical removal in minimizing recurrences has been established.24,25 The area is then covered with a pericranial flap, with the fascia of the temporal muscle, or—as we prefer—with a galeal–periosteal flap, and sealed with fibrin glue.

Extended Transsphenoidal Approaches

Emerging alternatives to the transcranial route for removal of SM are the extended transsphenoidal approaches, either with the microscopic or the endoscopic technique.26–34 The exposure of the suprasellar region via this route is made possible by resection of the bone of the tuberculum sellae and the posterior planum sphenoidale between the optic canals. A major advancement is the introduction of the endoscopes with their great illuminating power, wider viewing angle, and ability to look around corners, as well as the elaboration of the extended endonasal surgical concept.28,32,35,36

Authors using this technique propagate that it is superior to the transcranial approaches because it should avoid brain lesion, otherwise caused by brain retraction. Further, they argue that the more direct manipulation of the optic nerves/chiasm is minimized and the pituitary gland and infundibulum are identified early, thus increasing the likelihood of their preservation.37 Further, early and direct approach to the dural attachment of the tumor is possible. Respectively, the meningioma is devascularized initially and an almost bloodless tumor debulking can be performed.

Recently, several series of SM removed via the endonasal transsphenoidal route have been published.28,32,35,38 However, the number of patients included is still insufficient and the follow-up too short to allow a definitive estimations of the technique. At present SMs that are relatively large and asymmetric, with encasement of main vessels and invasion of one or both optic canals, are not suitable for transsphenoidal removal. A drawback of the approach is that the neurovascular structures, such as the anterior communicating artery complex, lie “behind” the dissection trajectory and are visualized late. Further, the restricted working space, the two-dimensional view, and lack of appropriate instruments, make manipulations and dissection in these critical areas more dangerous. Our experience has shown that not infrequently the meningioma extends into the optic canal even though this is not visible on the preoperative imaging studies. Via the transsphenoid route, access to the whole circumference of the optic nerve is impossible. A major challenge remains the reconstruction of the osteodural defect, especially in meningiomas with large attachments, and the reported rates of CSF leak are unacceptably high—up to 30%.28,32,37,38

OUTCOME

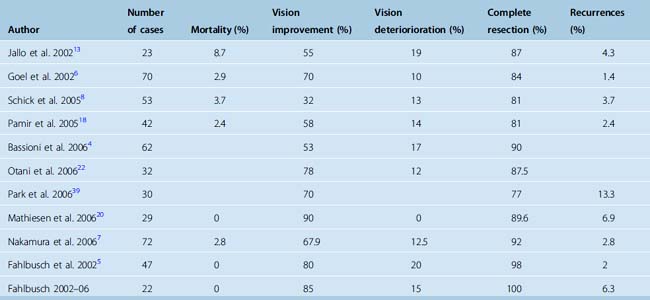

The mortality rate in recent series ranges from 0 to 8.7%.6,7,13,18,39 The morbidity is related to visual deterioration; hypothalamic or pituitary dysfunction, such as diabetes insipidus; injury to olfactory nerves; CSF leaks; meningitis; cerebral infarction; or hemorrhage. According to our experience, endocrine disturbances are rare but might be a more important factor in very large tumors.5 The most frequent complication is diabetes insipidus with a rate between 0 and 33%.3,5,7,17

Postoperative visual impairment occurs in 10% to 20% and might be a sequela of a variety of factors, including direct damage to the optic nerve or chiasm, interruption of their vascular supply, or compression.3 As noted by Gallo and colleagues,13 the key to prevent these complications is to avoid direct manipulation or trauma to the optic nerves, as well as of injury to the blood supply of the optic apparatus.

Visual improvement rates ranging from 25% to 85% have been reported.5,7,8,11,17,18,38 In the series of the senior author 85% of the patients displayed visual improvement after surgery and in 26% of them visual acuity and visual fields could be normalized. Among the variables influencing visual outcome are tumor size,9 patient age, and duration and degree of visual compromise.5 One of the major factors, more important than the tumor size, is the duration of visual deterioration before surgery.5,7,20 The improvement rate is significantly higher in case the visual symptoms are lasting less than 6 months.7,9 Some authors indicate that the risk of visual deterioration is not dependent on preoperative visual level.7 However, we found that there is a risk of 8% for good preoperative vision to become worse after surgery compared with 19% in patients with poor preoperative vision. The long-term chance of visual improvement is related to the early postoperative visual function: a tendency to improve in the long-term exists if short-term postoperative visual function showed favorable outcome.15

The rate of tumor recurrence in 3 to 10 years of follow-up is from 0 to 12%. The main predicting factors for recurrence are the extent of tumor resection, the duration of the postoperative follow-up, the mode and quality of the assessment of tumor recurrence, and the histologic features of the tumor.5 Some data suggest, however, that recurrences reflect primarily nonradical surgery and that Simpson grade 1 tumor removal would decrease the risk of recurrences. Thus, Mathiesen and colleagues24 reported that the six recurrent tumors in their series did not show aggressive histopathologic features or high levels of MIB-1/Ki-67 expression. Operative results are summarized in Table 28-1.

[1] Cushing H., Eisenhardt L. Meningiomas arising from the tuberculum sellae, with syndrome of primary optic atrophy and bitemporal field defects combined with normal sella turcica in middle aged person. Arch Ophthalmol. 1929;1:1-41. 168–206

[2] Cushing H., Eisenhardt L. Suprasellar meningiomas. In: Meningiomas: Their Classification, Regional Behaviour, Life History, and Surgical End Results. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1938:224-249.

[3] Al-Mefty O., Smith R.R. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas. In: Al-Mefty O., editor. Meningiomas. New York: Raven Press; 1991:395-411.

[4] Bassiouni H., Asgari S., Stolke D. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: functional outcome in a consecutive series treated microsurgically. Surg Neurol. 2006;66:37-44.

[5] Fahlbusch R., Schott W. Pterional surgery of meningiomas of the tuberculum sellae and planum sphenoidale: surgical results with special consideration of ophthalmological and endocrinological outcomes. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:235-243.

[6] Goel A., Muzumdar D., Desai K.I. Tuberculum sellae meningioma: A report on management on the basis of a surgical experience with 70 patients. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:1358-1364.

[7] Nakamura M., Roser F., Struck M., et al. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: clinical outcome considering different surgical approaches. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:1019-1028.

[8] Schick U., Hassler W. Surgical management of tuberculum sellae meningiomas: involvement of the optic canal and visual outcome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:977-983.

[9] Andrews B.T., Wilson C.B. Suprasellar meningiomas: The effect of tumor location on postoperative visual outcome. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:523-528.

[10] Brihaye J., Brihaye-van Geertruyden M. Management and surgical outcome of suprasellar meningiomas. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien). 1988;42:124-129.

[11] Puchner M.J., Fischer-Lampsatis R.C., Hermann H.D., Freckmann N. Suprasellar meningiomas-neurological and visual outcome at long-term follow-up in a homogeneous series of patients treated microsurgically. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1998;140:1231-1238.

[12] Gokalp H.Z., Arasil E., Kanpolat Y., et al. Meningiomas of the tuberculum sella. Neurosurg Rev. 1993;16:111-114.

[13] Jallo G.I., Benjamin V. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: Microsurgical anatomy and surgical technique. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:1432-1440.

[14] Olivecrona H. The suprasellar meningiomas. In: Olivecrona H., Tönnis W., editors. Handbuch der Neurochirurgie. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1967:167-172.

[15] Chi J.H., McDermott M.W. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;14(6):e6.

[16] Ciric I., Rosenblatt S. Suprasellar meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:1372-1377.

[17] Symon L., Rosenstein J. Surgical management of suprasellar meningioma. Part 1: The influence of tumor size, duration of symptoms, and microsurgery on surgical outcome in 101 consecutive cases. J Neurosurg. 1984;61:633-641.

[18] Pamir M.N., Ozduman K., Belirgen M., et al. Outcome determinants of pterional surgery for tuberculum sellae meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2005;147:1121-1130.

[19] Benjamin V., Russell S.M. The microsurgical nuances of resecting tuberculum sellae meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(Suppl. 5):411-417.

[20] Mathiesen T., Kihlström L. Visual outcome of tuberculum sellae meningiomas after extradural optic nerve decompression. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:570-576.

[21] Nakamura M., Roser F., Jacobs C., et al. Medial sphenoid wing meningiomas: clinical outcome and recurrence rate. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:626-639.

[22] Otani N., Muroi C., Yano H., et al. Surgical management of tuberculum sellae meningioma: role of selective extradural anterior clinoidectomy. Br J Neurosurg. 2006;20:129-138.

[23] Lang J. Clinical Anatomy of the Head. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1983.

[24] Mathiesen T., Lindqvist C., Kihlstrom L., et al. Recurrence of cranial base meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1996;39:2-9.

[25] Pieper D.R., Al-Mefty O., Hanada Y., et al. Hyperostosis associated with meningioma of the cranial base: Secondary changes or tumor invasion. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:742-747.

[26] Arai H., Sato K., Okuda O., Miyajima M., Hishii M., Nakanishi H., Ishii H. Transcranial transsphenoidal approach for tuberculum sellae meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2000;142:751-757.

[27] Couldwell W.T., Weiss M.H., Rabb C., et al. Variations on the standard transsphenoidal approach to the sellar region, with emphasis on the extended approaches and parasellar approaches: surgical experience in 105 cases. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:539-550.

[28] de Divitiis E., Cavallo L.M., Esposito F., et al. Extended endoscopic transsphenoidal approach for tuberculum sellae meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2007;61(Suppl. 2):229-237.

[29] Honegger J., Fahlbusch R., Buchfelder M., et al. The role of transsphenoidal microsurgery in the management of sellar and parasellar meningioma. Surg Neurol. 1993;39:18-24.

[30] Jane Jr J.A., Dumont A.S., Vance M.L., et al. The transsphenoidal transtuberculum sellae approach for suprasellar meningiomas. Semin Neurosurg. 2003;14:211-218.

[31] Kaptain G.J., Vincent D.A., Sheehan J.P., et al. Transsphenoidal approaches for the extracapsular resection of midline suprasellar and anterior cranial base lesions. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:94-101.

[32] Gardner P.A., Kassam A.B., Thomas A., et al. Endoscopic endonasal resection of anterior cranial base meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2008;63:36-54.

[33] Kitano M., Taneda M. Extended transsphenoidal approach with submucosal posterior ethmoidectomy for parasellar tumors: Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:999-1004.

[34] Laws E.R., Kanter A.S., Jane J.A.Jr, et al. Extended transsphenoidal approach. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:825-828.

[35] de Divitiis E., Esposito F., Cappabianca P., et al. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: high route or low route? A series of 51 consecutive cases. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:556-563.

[36] Jho H.D., Ha H.G. Endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery: Part 1—The midline anterior fossa skull base. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2004;47:1-8.

[37] Cook S.W., Smith Z., Kelly D.F. Endonasal transsphenoidal removal of tuberculum sellae meningiomas: technical note. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:239-246.

[38] Laufer I., Anand V.K., Schwartz T.H. Endoscopic, endonasal extended transsphenoidal, transplanum transtuberculum approach for resection of suprasellar lesions. J Neurosurg. 2007;106:400-406.

[39] Park C.K., Jung H.W., Yang S.Y., et al. Surgically treated tuberculum sellae and diaphragm sellae meningiomas: the importance of short-term visual outcome. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:238-243.