13 Superficial to Medium-Depth Peels

A Personal Experience

Introduction

Chemical peeling as a therapeutic modality for acne has many benefits:

The Problem Being Treated

• Patient selection

The success of a chemical peel depends on careful selection of patient and individualization of treatment. Patients with mild facial rhytides and/or minimal dyschromias are the best candidates for superficial to medium-depth chemical peels. Deep rhytides and excessive facial laxity are likely to best respond to traditional rhytidectomy as the primary procedure and chemical peeling as an adjunct. Careful evaluation of skin type and complexion is the first step. The Fitzpatrick classification of skin types (I–VI) is often used to help stratify a patient’s risk for pigmentary complications. Darker phototypes are at higher risk for developing postpeel hyperpigmentation especially after more aggressive peels, while lighter phototypes seem to be more susceptible to excessive penetration of the peeling agent. In all cases, careful monitoring during the procedure is prudent (Boxes 13.1, 13.2, Table 13.1).

Box 13.1

An example of significant improvement in MASI score, after peeling treatment, from baseline to T3

| Facial Areas | TOTAL MASI SCORE |

|---|---|

| F + RM + LM | 12.6 |

| Facial Areas | TOTAL MASI SCORE |

|---|---|

| F + RM + LM | 3.6 |

Box 13.2

Wrinkle severity rating scale (WSRS)

| Score | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Absent: No visible fold; continuous skin line. Amelioration with TCA peels |

| 2 | Mild: Shallow but visible fold with a slight indentation; minor facial feature; improvement in skin texture with TCA peels |

| 3 | Moderate: Moderately deep folds; clear facial feature visible at normal appearance but not when stretched. Excellent correction with phenol peels |

| 4 | Severe: Very long and deep folds; prominent facial feature; less than 2 mm visible fold when stretched. Significant improvement expected with combined peels |

| 5 | Extreme: Extremely deep and long folds detrimental to facial appearance; 2–4 mm visible V-shaped fold when stretched. Unlikely to have satisfactory correction with medium and deep peelings alone |

Table 13.1 Correlation among skin diseases and suggested peeling approach

| Skin disease | Diagnostic method | Suggested approach |

|---|---|---|

| Comedonal Acne-papulo-pustular | Global scorea |

Box scar

a Doshi A, Zaheer A, Stiller MJ 1997 A comparison of current acne grading systems and proposal of a novel system. International Journal of Dermatology 38:416–418

c Day DJ, Littler CM, Swift RW, Gottlieb S 2004 The wrinkle severity rating scale: a validation study. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology 5(1):49–52

d Goodman GJ, Baron JA 2006 Postacne scarring: a qualitative global scarring grading system. Dermatologic Surgery 32:1458–1466

Treatment Approach

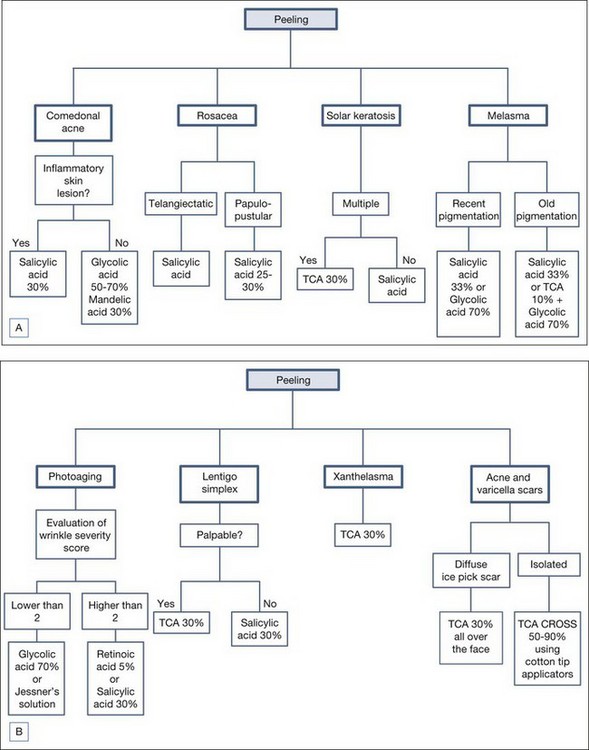

Standard baseline photography and an informed consent are always obtained prior to the procedure. Since the choice of the peeling agent is a very important step, we have recently developed a flowchart that can help doctors in the evaluation and management of potential candidates for chemical peels (see Figure 13.1).

• Major determinants

Table 13.2 summarizes the main factors that can influence therapeutic efficacy and side effects of different chemical peels.

Table 13.2 Main factors that can influence therapeutic efficacy and side effects of different chemical peels

| Chemical peel | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Pyruvic acid | Very mild erythema Mild desquamation Short postoperative period Can be used in skin types III and IV Excellent for acne |

Intense stinging and burning sensation during application Requires neutralization Pungent and irritating vapors for the upper respiratory mucosa |

| Salicylic acid | Excellent for acne Given the appearance of the white precipitate, uniformity of application is easily evaluated The peel induces an anesthetic effect that increases patient tolerance Established safety profile in patients with skin types I–VI |

Minimal efficacy in patients with significant photodamage Limited depth of peeling |

| Resorcinol | Easy to perform Uniformity of application and penetration Useful in acne, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and melasma Not painful (the burning sensation during the peeling is usually mild) |

Cannot be used in summer Resorcinol may cause allergic and toxic reactions Unsafe in Fitzpatrick skin type higher than V Desquamative effect aesthetically unacceptable |

| Trichloracetic acid | Low-cost procedure Uniformity of application and penetration Evaluation of the frost, permits easy to modulate depth of penetration |

Stinging and burning sensation during the application High concentrations are not recommended in skin types V and VI Hypo/hyperpigmentation can occur |

| Combination peels: Salicylic acid + TCA | Efficacy in all skin types Well tolerated in darker racial/ethnic groups Most beneficial in treating recalcitrant melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation |

Increase penetration of superficial peeling Increased desquamation in some patients lasting up to 7–10 days Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation more common than with salicylic acid peeling alone |

| Glycolic acid | Very mild erythema Mild desquamation Short postoperative period Useful in photodamage |

Burning sensation and erythema during application No uniformity of application Requires neutralization Necrotic ulcerations if time of application is too long and/or skin pH is reduced Cautious application in patients with active acne |

| Jessner’s solution | Excellent safety profile Can be used in all skin types Substantial efficacy with minimal ‘downtime’ Enhances the penetration of TCA peel |

Concerns regarding resorcinol toxicity, including thyroid dysfunction Manufacturing variations Instability with exposure to light and air Excessive exfoliation in some patients |

• Patient interview

To better select the right patient for the right peel it is important to obtain a detailed history that evaluates all potential risks linked to the peeling agents. It is important to identify all potential factors that may adversely affect the outcome of a peel and fully characterize a patient’s skin type and propensity to scar and hyperpigment (see Table 13.3).

Table 13.3 Suggested questions and possible answers and discussion for patient interviews

| Questions | Possible answers and discussion |

|---|---|

| Do you have sensitive skin? | Sensitive skin can develop adverse reactions even with superficial peels at low concentration. |

| Are you pregnant or breast-feeding? | Some peels, such as salicylic acid, should be avoided in pregnant and breast-feeding women. |

| Are you allergic to topical or systemic drugs? | Patients with glycolate hypersensitivity cannot be treated with glycolic acid; allergy to resorcinol, salicylic acid, or lactic acid are absolute contraindications to Jessner’s solution |

| Have you been treated with isotretinoin therapy within the last 6 months? | This is a contraindication to deeper chemical peels |

| What do you expect from this treatment? | Patients should not have unrealistic expectations |

| Do you have recurrent herpes simplex virus infection? | History of recurrent herpes simplex virus infection requires systemic prophylaxis with antivirals starting a day before the procedure and continuing for 10 days until full reepithelilization |

Treatment Techniques

• Salicylic acid

Salicylic acid is a naturally occurring substance found in the bark of the willow tree. In concentrations of 3–5%, it acts as a keratolytic agent and enhances the penetration of other peeling agents. It is also a well-documented comedolytic agent. Salicylic acid is one of the oldest peeling agents with first documented use by Unna, a German dermatologist. Salicylic acid is a flexible substance that can be formulated in many types of vehicles. In our experience, salicylic acid is the best peeling agent for acne and macular acne scars (Figure 13.2), hyperpigmentation, melasma, and rosacea. Side effects are rare even in darker skin types.

• Trichloroacetic acid

The most common indications we use TCA peels to treat are solar lentigos and severe acne scars (Figure 13.3). TCA can also be combined with salicylic acid for treatment of solar lentigos. For the treatment of recalcitrant hyperpigmentation and melasma, TCA can be combined with salicylic acid or glycolic acid.

Advanced Topics: Treatment Tips for Experienced Practitioners

In a recent study, we proposed an innovative method for the treatment of acne scars and chickenpox scars. If only a few isolated scars are present on a background on healthy skin, the best method is TCA CROSS (chemical reconstruction of skin scars). This method involves local serial applications of high concentration TCA (50% to skin scars with sharpened wooden applicators). The wooden end of cotton-tipped applicators can be sharpened to a dull point using number 10 blade to approximate the shape of the scar. No local anesthesia or sedation is needed to perform this technique. TCA is applied for a few seconds until white frosting is present in the scar. We then prescribe emollients for 7 days after, and high photoprotection. In our study, we repeated the procedure at 4-week intervals, and each patient received a total of three treatments. We opted to use a reduced concentration of TCA (50%) instead of 100% TCA which was first described in the study by Lee and colleagues. We demonstrated excellent cosmetic outcomes without significant adverse reactions. Of note, this precise technique can be used for focal chemical scar reconstruction without the prolonged downtime associated with classic full-face chemical resurfacing. Moreover, compared with other procedures, this technique can minimize or avoid the potential risks of scarring and dyspigmentation by sparing the adjacent normal skin and adnexal structures. The CROSS technique with 50% TCA is in our hands a very useful approach for the treatment of acne scars (Figure 13.4).

Case Studies

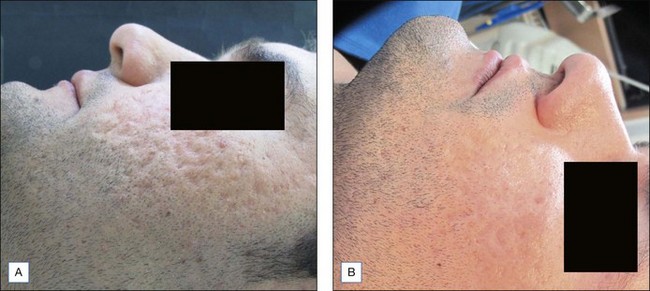

• Case study 1: a patient with acne scars successfully treated with 30% TCA peeling

The patient had acne scars (Fig 13.5A). He had been previously treated with 30% salicylic acid and 50% glycolic acid peels without improvement. We decided to perform three 30% TCA peels at 4 week intervals. Photoprotection with SPF total block was recommended and alpha hydroxyacids were prescribed for topical application 4 times a week. The patient experienced good results after the second peeling with only mild transient erythema lasting 48 hours. Emollients were applied after each peeling. No burns or desquamation were observed until the third peeling. The results showed improvement of acne scars of about 70% and the patient was very satisfied with this course of therapy (Fig. 13.5B). Profilometry performed before and after treatments to evaluate reduction of roughness and deepness of the scars showed a reduction of about 65% in selected areas.

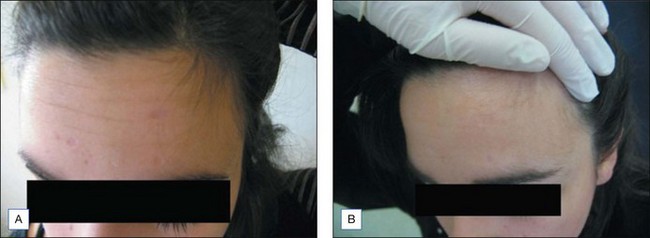

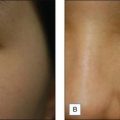

• Case study 2: a patient with macular acne scars successfully treated with peels

The patient consulted us regarding macular acne scarring. After preparation with sunscreens and 10% glycolic acid lotion at night for 2 weeks, she was treated with 30% salicylic acid peels once a month for 3 consecutive months. Figure 13.6 shows the remarkable improvement of skin texture and macular spots.

Azzam OA, Leheta TM, Nagui NA. Different therapeutic modalities for treatment of melasma. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2009;8:275-281.

Clark E, Scerri L. Superficial and medium-depth chemical peels. Clinics in Dermatology. 2004;26:209-218.

Day DJ, Littler CM, Swift RW, Gottlieb S. The wrinkle severity rating scale: a validation study. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 2004;5:49-52.

Erbil H, Sezer E, Taştan B, et al. Efficacy and safety of serial glycolic acid peels and a topical regimen in the treatment of recalcitrant melasma. Journal of Dermatology. 2007;34:25-30.

Fabbrocini G, De Padova MP, Tosti A. Chemical peels: what’s new and what isn’t new but still works well. Facial Plastic Surgery. 2009;25:329-336.

Fischer TC, Perosino E, Poli F, et al. Chemical peels in aesthetic dermatology: an update 2009. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2010;24:281-292.

Haygood LJ, Bennett JD, Brodell RT. Treatment of xanthelasma palpebrarum with bichloracetic acid. Dermatological Surgery. 1998;24:1027-1031.

Khunger N, Sarkar R, Jain RK. Tretinoin peels versus glycolic acid peels in the treatment of Melasma in dark-skinned patients. Dermatological Surgery. 2004;30:756-760.

Khunger N. Standard guidelines of care for chemical peels. http://www.ijdvl.com, 2008. (accessed March 2009)

Landau M. Chemical peels. Clinics in Dermatology. 2008;26:200-208.

Tosti A, Grimes PE, De Padova MP. Color atlas of chemical peels. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2006.

Zakopoulou N, Kontochristopoulos G. Superficial chemical peels. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2006;5:246-253.