Chapter 25 Suicide and Attempted Suicide

Epidemiology

Suicide Completions

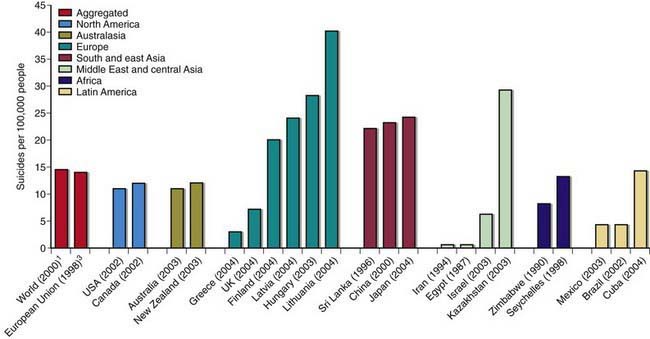

Suicide is very rare before puberty. Rates of completed suicide increase steadily across the teen years and into young adulthood, peaking in the early 20s. Males complete suicide at a rate 4 times that of females and represent 79.4% of all suicides. Firearms remain the most commonly used method of completing suicide for males, whereas females are more likely to complete suicide by poisoning (Fig. 25-1). In the past 60 yr, the suicide rate has quadrupled among 15-24 yr old males and has doubled for females of the same age. The male:female ratio for completed suicide rises with age from 3 : 1 in young children to approximately 4 : 1 in 15-24 yr olds, and to greater than 6 : 1 among 20-24 yr olds.

Figure 25-1 Annual suicide rates among persons aged 15-19 yr, by year and method, United States, 1992-2001.

(From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Methods of suicide among persons aged 10–19 years, United States, 1992–2001, MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 53:471–474, 2004.)

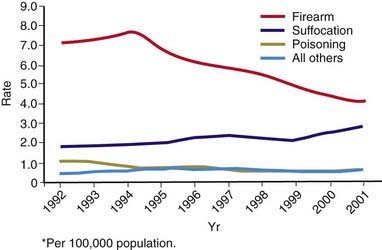

The ethnic groups with the highest risk for completed suicide are American Indians and Alaska Natives. Within this population, suicide is the second leading cause of death, accounting for nearly 1 in 5 deaths among youth ages 15-24 yr. The ethnic groups with the lowest risk are African-Americans, Hispanics, Asians, and Pacific Islanders. The suicide rate among African-American, Hispanic, and other minority males has continued to increase, and the rate among white males has remained steady. Suicide risk also varies in different countries (Fig. 25-2).

Risk Factors

Pre-existing Psychiatric Illness

The great majority (estimated at 90%) of youths who complete suicide have a pre-existing psychiatric illness, most commonly major depression (Chapter 24.1). Among girls, chronic anxiety, especially panic disorder, also is associated with suicide completion (Chapter 23). Among boys, conduct disorder and substance use convey increased risk. Comorbidity of a substance use disorder (Chapter 108), a mood disorder (Chapter 24), and conduct disorder (Chapter 27) has been linked to suicide by firearm.

Assessment and Intervention

The assessment of attempts should include a detailed exploration of the hours immediately preceding the attempt to identify precipitants, as well as the circumstances of the attempt itself to identify intent and potential lethality. Attempters at greatest risk for completed suicide are those who are male; have made a prior suicide attempt; have current ideation, intent, a written note, and a plan; have a mental status altered by depression, mania, anxiety, intoxication, psychosis, hopelessness, rage, humiliation, or impulsivity; and lack supportive family members who can provide supervision, safeguard the home (prevent access to firearms, medications, alcohol, drugs), and ensure adherence to treatment recommendations (Table 25-1).

Table 25-1 CHECKLISTS FOR ASSESSING CHILD OR ADOLESCENT SUICIDE ATTEMPTERS IN AN EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT OR CRISIS CENTER

ATTEMPTERS AT GREATER RISK FOR SUICIDE

Suicidal History

Demographics

Mental State

LOOK FOR SIGNS OF CLINICAL DEPRESSION:

LOOK FOR SIGNS OF MANIA OR HYPOMANIA:

From American Foundation for Suicide Prevention: Today’s suicide attempter could be tomorrow’s suicide (poster), New York, 1999, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, 1-888-333-AFSP.

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with suicidal behavior. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:24S-51S.

American Association of Suicidality. Fact sheets. (website) www.suicidology.org/web/guest/stats-and-tools/fact-sheets Accessed February 12, 2010

Aseltine RH, DeMartino R. An outcome evaluation of the SOS Suicide Prevention Program. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:446-451.

Brent DA, Emslie GJ, Clarke GN, et al. Predictors of spontaneous and systematically assessed suicidal adverse events in the treatment of SSRI-resistant depression in adolescents (TORDIA) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:418-426.

Brezo J, Barker ED, Paris J, et al. Childhood trajectories of anxiousness and disruptiveness as predictors of suicide attempts. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 162, 2008. 1813–1021

Bridge JA, Greenhouse JB, Weldon AH. Suicide trends among youths aged 10 to 19 years in the United States, 1996-2005. JAMA. 2008;300:1025-1026.

Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, et al. Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment. JAMA. 2007;297:1683-1696.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol and suicide among racial/ethnic populations—17 states, 2005-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:637-642.

Hawton K. Completed suicide after attempted suicide. BMJ. 2010;341:c3064.

Hawton K, van Heeringen K. Suicide. Lancet. 2009;373:1372-1380.

Klomek Brunstein A, Sourander A, Niemela S, et al. Childhood bullying behaviors as a risk for suicide attempts and completed suicides: a population-based birth cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:254-261.

Kuchar PS, DiGuiseept C. Screening for suicide risk. In: Guide to clinical preventive services, second edition: mental disorders and substance abuse. Washington, DC: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; 2003.

National Institute of Mental Health. Suicide in the U.S.: statistics and prevention. (website) www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/suicide-in-the-us-statistics-and-prevention/index.shtml Accessed February 12, 2010

Qin P, Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB. Frequent change of residence and risk of attempted and completed suicide among children and adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:628-632.

Schneeweiss S, Patrick AR, Solomon DH, et al. Comparative safety of antidepressant agents for children and adolescents regarding suicidal acts. Pediatrics. 2010;125:876-888.

Wilcox HC, Storr CL, Breslau N. Posttraumatic stress disorder and suicide attempts in a community sample of urban American young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:305-311.

Winters NC, Myers K, Proud L. Ten-year review of rating scales. III: Scales assessing suicidality, cognitive style, and self-esteem. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:1150-1181.