82 Substance Abuse

Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

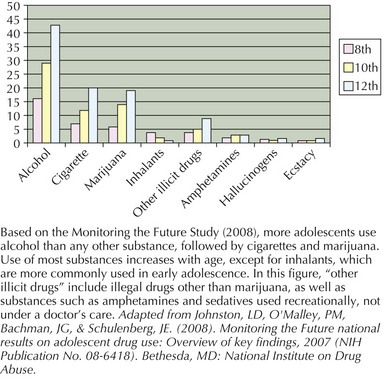

Patterns of drug initiation and drug use vary by age, gender, race, ethnicity, and substance availability in an adolescent’s community. Monitoring the Future Study (MTFS) is a nationally representative study that follows trends in adolescent drug use and attitudes. As adolescents mature, they report higher rates of substance use (Figure 82-1). Notably, alcohol is the most commonly reported substance used by adolescents followed by cigarette use and marijuana use. Use of other illicit drugs substances, although less common, poses risks resulting from acute impairments in judgment or long-term addiction. More recent surveys have highlighted the increased availability and recreational use of prescription drugs such as hydrocodone bitartrate (Vicodin), oxycodone (Percocet), and methylphenidate hydrochloride (Ritalin). Although illicit substances can signify an increased risk for an individual adolescent, pediatricians need to routinely discuss alcohol-related issues given that 43% of 12th graders; 29% of 10th graders; and 16% percent of 8th graders reported using alcohol based on 2008 MTFS data. Although adolescents drink less frequently than adults, when consuming alcohol, teens tend to drink more at one time compared with adults. Remarkably, from the same survey, 25% of 12th graders, 16% of 10th graders, and 8% of 8th graders report having consuming five or more drinks on at least one occasion.

Pediatricians will find that a substantial proportion of their adolescent patients will report trying substances, yet of these teens, only a minority will abuse a substance or become physiologically dependent (Figure 82-2). Progression from experimentation to abuse or physiologic dependence results from the complex interplay of numerous biopsychosocial risks and protective factors, including adolescent physical, emotional, and cognitive development, and environmental factors, including peers’ and family’s attitudes and behaviors, genetic predisposition, and mental health stressors.

Mental health issues and past traumas can increase the risk that an adolescent will begin using substances on a regular basis to elevate mood, dull anxiety, or avoid feelings altogether. Adolescents with depression, anxiety, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and conduct disorders are at significantly increased risk for using substances to manage symptoms related to these disorders (Figure 82-3). A history of having experienced childhood physical or emotional abuse, past or ongoing family conflict, inadequate parental supervision, isolation from school, poor academic achievement, and sexual or gender identity concerns can increase the risk that an adolescent may begin to use and experience harm from substances.

Evaluation and Clinical Presentation

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update, a Public Health Service-sponsored Clinical Practice Guideline. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?rid=hstat2.chapter.28163

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/index.htm

Kulig JW, the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Substance Abuse. Tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs: the role of the pediatrician in prevention, identification, and management of substance abuse. Pediatrics. 2005;115(3):816-821.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Available at http://www.niaaa.nih.gov

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Available at http://www.nida.nih.gov

Office of National Drug Control Policy. Listing of Drug Street Names. Available at http://www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/streetterms/default.asp

Regents of the University of Michigan. Monitoring the Future. Available at http://www.monitoringthefuture.org

Steinberg L. Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends Cognitive Sci. 2005;9(2):69-74.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Available at http://www.samhsa.gov

Toumbourou JW, Stockwell T, Neighbors C, et al. Interventions to reduce harm associated with adolescent substance use. Lancet. 2007;369:1391-1401.