Chapter 45 Suboccipital Retrosigmoid Surgical Approach for Vestibular Schwannoma (Acoustic Neuroma)

For the surgery of vestibular schwannoma (acoustic neuroma), refinements of microsurgical techniques, combined with improvements in intraoperative monitoring of facial and cochlear nerve function and advances in neuroimaging, have resulted in the shift of focus from reduction of mortality to optimizing facial nerve function,1–4 hearing preservation,1,2,5 and preservation of other cranial nerves.6 Facial nerve dysfunction is a major concern among patients undergoing unilateral vestibular schwannoma surgery, and loss of useful hearing can be debilitating.7 Patients with vestibular schwannoma have many options, including watchful waiting, radiosurgery, fractionated radiation, and surgery through one of several routes: translabyrinthine, middle fossa, or suboccipital retrosigmoid. The ideal treatment strategy depends on several factors, including the age, medical condition, and hearing status of the patient and the anatomy of the tumor as seen on imaging studies. Surgeons generally try to save hearing if the speech discrimination is above 50% and the average pure tone loss is less than 50 dB.8,9 However, even worse hearing is worth saving in some circumstances, such as when poor hearing is present on the contralateral side or in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2), where bilateral hearing loss could later occur. Moreover, these various treatments are not mutually exclusive; in some patients, a combination of subtotal surgical tumor removal followed by radiosurgery of the residual may prove appropriate.

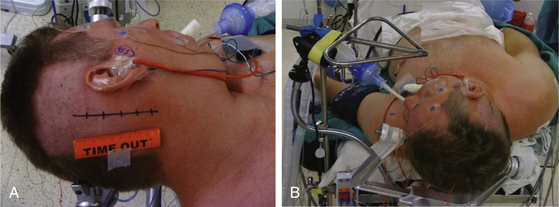

The patient is positioned supine with one or two folded soft cotton blankets beneath the ipsilateral shoulder and padding beneath the knees and is secured with one or two belts to allow the table to be rolled if necessary during surgery. For patients with a cervical tumor (as in NF2) or elderly patients with cervical spondylosis or limitations in neck movement, additional blankets are used to further turn the upper body of the patient and thereby require less turning of the neck. However, too much turning of the body can place the shoulder in a position that interferes with surgery. To prevent peripheral neural compression, the surgeon must ensure the contralateral ulnar and fibular head areas will not be under pressure if the bed is rolled and pad them appropriately. The head is gently turned toward the contralateral side. Hair is shaved from about 7 cm behind the ipsilateral ear, and the patient is fixed in a three-pin headrest (Fig. 45-1A). The surgeon must assure that there is adequate space between the chin and the clavicle and that contralateral jugular compression is avoided. Physiologic monitoring equipment is placed. Bipolar facial monitoring electrodes are routinely placed in the orbicularis oculi and orbicularis oris. If trigeminal nerve function is of concern, an additional electrode is placed in the masseter. For hearing monitoring, the ear canal is inspected and cleaned if necessary; an electronic clicker is placed in the ipsilateral ear and the contralateral ear, with electrodes in the scalp to record a brain stem auditory evoked response (BAER) during surgery. If lower cranial nerves are involved, we use an endotracheal tube with an embedded electrode.

The self-retaining retractor post is secured to the side of the headrest away from the surgical site. A metal triangle is used to protect the face and allow both the anesthesiologist and the neurophysiologist or audiologist visualization of the airway and of facial movement. The endotracheal tube exits the mouth on the contralateral side to avoid distortion of the ipsilateral lip and cheek. A fiberoptic tube delivers a cool but bright light to the area under the drapes and assures that the small TV camera also under the drapes has a well-illuminated view of the patient’s ipsilateral face (Fig. 45-1B). Stimulation of the facial nerve in the operative field causes a clearly visible “smile” reaction, which can be seen on the external TV monitors. In contrast, electric activity that causes stimulation of the motor branch of the trigeminal nerve in turn causes jaw movements due to activation of the masseter muscle. An audiologist or neurophysiologist monitors facial movements, electromyogram (EMG), and BAER throughout the procedure.

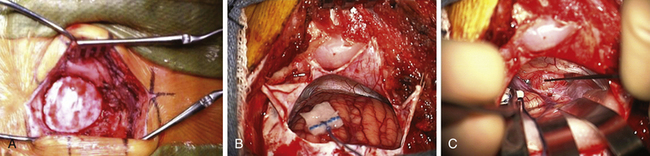

The area behind the operative ear and an area on the ipsilateral abdomen are sterilely prepared and draped for surgery. A linear incision is made approximately 3 cm behind the insertion of the pinna and going from approximately 1 cm above the tip of the pinna to 1 cm below the ear lobe. Superiorly, a 3-cm piece of pericranium is removed and placed in sterile solution during the procedure for later use in closing the dural defect. The muscles are then divided inferiorly, hemostasis is obtained, and two muscle self-retaining retractors are placed. They are angled such that the medial skin area is free from these muscle retractors, because that is where the cerebellar retractors will later be situated (Fig. 45-2A).

The incisional area is surrounded with antibiotic-soaked sponges and towels in preparation for dural opening. The dura is opened with a linear vertical incision approximately 2 cm medial to the edge of the sigmoid sinus. The medial dura is left intact to protect the cerebellum. Additional dural incisions are made laterally toward the edge of the venous sinuses. The resulting triangular-shaped dural leaves are sutured to the surrounding tissue with 4-0 Vicryl sutures. An adjustable bar is attached to the retractor bar that previously had been affixed to the headrest, and a long flexible arm and long narrow retractor are attached. The inferior cerebellum is gently elevated with the retractor, and the arachnoid of the cistern is opened sharply to release CSF and provide for cerebellar relaxation. For larger tumors, a ventriculostomy catheter is put into the cistern, secured to the inferomedial dura with a 4-0 Vicryl suture, cut off at the dural edge, left in place for continuous CSF drainage throughout the procedure, and removed during closure. For smaller tumors, this is often unnecessary. At the time of initial dural opening, if the cerebellum is under a lot of pressure, it is often beneficial to open initially the most inferior triangular dural flap only and then release a small amount of CSF to allow the remainder of the dural opening to be performed under more controlled conditions. The surgeon must, however, be cautious not to remove too much CSF when the dura is not fully opened; doing so can be associated with too much cerebellar relaxation, causing a venous tear near the tentorium or in the area of the petrosal sinus. This can be difficult to control and forces a more rapid dural opening than might be desired.

Once the dura is opened and CSF removed, the cerebellum is generally relaxed and, in this position, falls away from the cerebellopontine angle because of gravity (Fig. 45-2B). A piece of moistened rubber dam covered with Telfa is placed on the cerebellum. Three long flexible arms and three long, 1⁄4-inch-wide self-retaining retractors are used. The retractors are placed on the Telfa with the tips on the cerebellum 1 or 2 mm proximal to the tumor edge. Care must be taken to be sure the retractors do not occlude important vascular structures or impinge on or stretch cranial nerves. They should be formed to sit securely on the skin edge to prevent unwanted movement. Occasionally, with a large tumor and an operculum of cerebellum overhanging the tumor, it is safer to resect the lateral cerebellar operculum than to retract it for long periods.

The operating microscope is engaged. At this point, stimulation of the posterior capsule of the tumor is necessary (Fig. 45-2C). I use a monopolar stimulator and first check it at 3 mA on the exposed neck muscles to be sure the stimulator is working and the patient is not pharmaceutically paralyzed. If muscle stimulation occurs, the stimulator is turned down to 1 mA and the posterior capsule is stimulated at all points to exclude a posteriorly placed facial nerve. If no stimulation is encountered, the tumor may be entered. In more than 80% of patients, the facial nerve is anterior or inferior. However, if stimulation occurs, the surgeon must determine whether this is due to transmission to a distant facial nerve or whether the nerve is indeed on the posterior tumor surface. To determine this, the posterior capsule is mapped out at sequentially lower milliampere levels to determine the course of the facial nerve. The surgeon must define an entry point into the tumor that is devoid of facial nerve fibers.

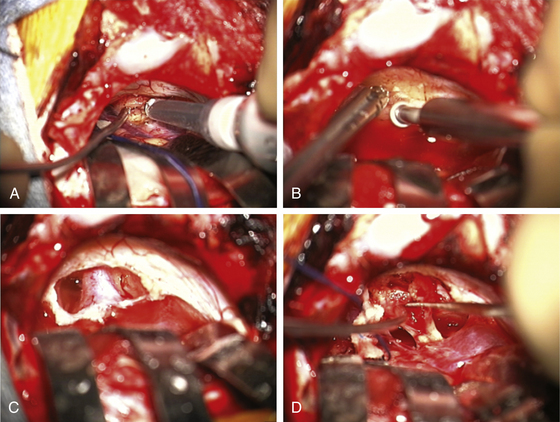

The surgeon must pay close attention to the arachnoid over the tumor. If this can be stripped away without coagulation, it provides not only the best plane for dissection but also a protective barrier for the cranial nerves and their small feeding vessels. After peeling away the arachnoid, a nonstimulating area on the posterior tumor is coagulated with bipolar cautery and opened with microscissors and specimens are sent for pathologic study. The internal portion of the tumor is then decompressed using an ultrasonic aspirator (Fig. 45-3A). Hemostasis is obtained, and the tumor capsule is dissected from the arachnoid plane and rolled inward. Depending on the size of the tumor, this process of internal decompression followed by dissection and inward rolling the capsule may need to be repeated several times. Each time, some of the capsule is also cut away but always leaving a visible portion to make the next round of microdissection easier. The retractors may need to be moved, but the surgeon must always keep them low profile, affixed to the skin, and with the tips on the cerebellum, not the cerebellar peduncle, brain stem, or critical blood vessels.

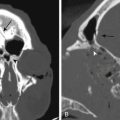

At some point, the limiting factor becomes the entry of the tumor into the internal auditory canal and its attachments at the medial edge of the canal. It then becomes necessary to open the canal. I usually work with an otologist to do this part. However, in some circumstances, the neurosurgeon may do this portion of the procedure. The superior and inferior lips of the internal auditory canal are defined. If there are open CSF cisterns, they are occluded with moistened gelfoam pledgets to prevent entry of bone dust. However, all patties with strings on them must be removed from the field prior to using a drill. The dura over the canal is coagulated and flapped medially. Using a suction-irrigator and high-speed diamond drill (Fig. 45-3B), the canal is opened to expose the dura of the canal (Fig. 45-3C). Attention is paid to air cells that will later need to be secured (Fig. 45-3C) and to a high jugular bulb if present. If hearing is being spared, the drilling of the canal should be limited to 10 mm or less and must not include the vestibular apparatus. Once drilling is completed, the entire operative field is washed clear of bone dust, the temporary gelfoam pledgets are removed, and the CSF spaces are irrigated with saline. The dura of the canal is then opened sharply.

For a case in which hearing is being spared, we do not necessarily define the facial nerve at this point in the canal; rather, because these are smaller tumors, we proceed to define the facial nerve medially as it enters the brain stem. The tumor can then be rolled medially to laterally, sparing both the facial and the cochlear nerves (Fig. 45-3D). There is often a nice arachnoid plane, and as the tumor is rolled into the canal, parts of the tumor may need to be removed to decrease the bulk. During the dissection of tumor off the facial nerve or cochlear nerves, the surgeon must minimize the use of bipolar cautery. If bleeding starts between the tumor and the facial nerve, it can often be stopped with irrigation or temporary application of Surgicel. Even using bipolar cautery at low levels can cause facial or cochlear nerve damage. Ultimately, the most lateral portion of the tumor can be removed with microdissectors. Ideally, the surgeon desires not only that the facial nerve be anatomically intact but also to stimulate at low milliamperes at the brain stem level and that a good wave V remains on the BAER.

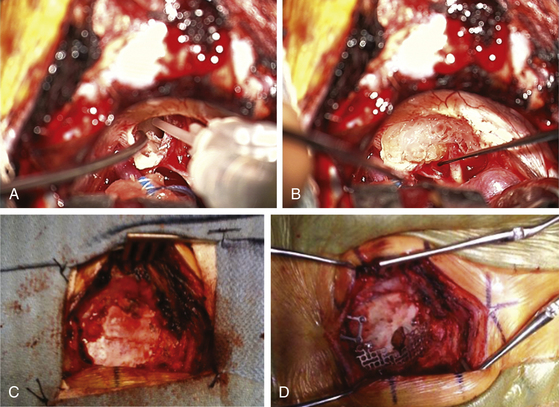

Once the tumor is removed and hemostasis is obtained, the internal auditory canal that has been drilled must be secured to prevent CSF leakage postoperatively. A 1-inch incision is made in the skin of the abdomen that had been previously prepared sterilely. A piece of subcutaneous adipose tissue is removed, hemostasis is obtained, and the incision is closed with 3-0 Vicryl sutures in the subcutaneous tissue plus a 4-0 Vicryl subcuticular closure and Steri-Strips. If large air cells are visible where the internal auditory canal had been drilled, some Tisseel or fibrin glue is placed within (Fig. 45-4A) and then packed with one or a few small pieces of adipose tissue covered with bone wax. The drilled surface of the canal is secured with bone wax, and a larger piece or multiple pieces of adipose tissue are then placed over the bone wax. This is covered with one piece of moistened surgicel to secure it to the surrounding dura (Fig. 45-4B). This is then further sealed and secured to the surrounding dura with Tisseel or fibrin glue.

The retractors are removed, along with the Telfa, rubber dam, and temporary CSF drainage tube that was placed in the cistern. All cottonoid patties and rubber dams are accounted for. The cerebellum should appear relaxed and away from the dura. The extra space is filled with sterile saline. The dura is then repaired using the previously removed pericranial graft and 4-0 Vicryl sutures (Fig. 45-4C), with two tenting sutures in the middle. The bone defect is then repaired with a construct consisting of the removed bone plus a preformed titanium mesh cranioplasty plate (Fig. 45-4D). The two dural tenting sutures of 4-0 Vicryl are threaded through this construct, and it is secured to the surrounding bone with a combination of miniplates and screws, taking care not to put any screws in an area of possible mastoid air cells. The tenting sutures are secured. The muscle retractors are removed, hemostasis is obtained, and the layers of muscle and the galea are reapproximated with 2-0 and 3-0 Vicryl. The skin is closed with running 3-0 monofilament nylon, and a sterile dry dressing is applied to this incision and the one on the abdomen.

Outcomes and The Importance of Cranial Nerve Monitoring

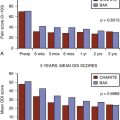

The importance of adequate cranial nerve monitoring must be emphasized. I had the opportunity to operate on 200 sequential patients in two centers where different monitoring techniques were used: center 1 (Massachusetts General Hospital, 1982 to 1991 and 2000 to 2001) and center 2 (Georgetown University Hospital, 1991 to 2000) using (1) only facial monitoring electrodes versus (2) electrodes plus mechanical means of verifying facial nerve stimulation or damage. Because the surgeries at center 2 occurred between the two surgical periods at center 1, changes that might occur with a later period are negated. In all, 164 patients (82%) underwent the suboccipital approach using the techniques noted earlier. (The others were done via the middle fossa or translabyrinthine approaches but are not the subject of this chapter.) Outcomes of vestibular schwannoma surgery, including facial nerve function, hearing preservation, neurologic function (other cranial nerves, cerebellar function, and gait) and postoperative complications, were evaluated.

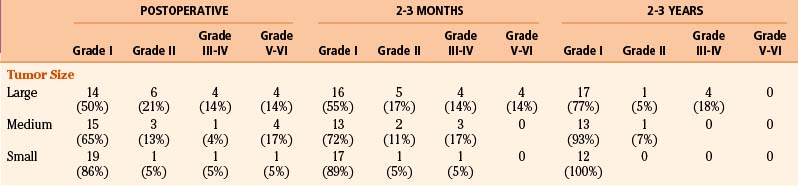

Hearing function preoperatively and postoperatively was classified using the Hanover classification.5 In cases where the speech discrimination score and pure tone average differed, the lower of the two was used to determine the patients’ hearing grade. The correlation between tumor size and hearing preservation, as well as preoperative hearing class and hearing preservation, were assessed. Regression and analysis of variance were performed utilizing the Minitab statistical software.

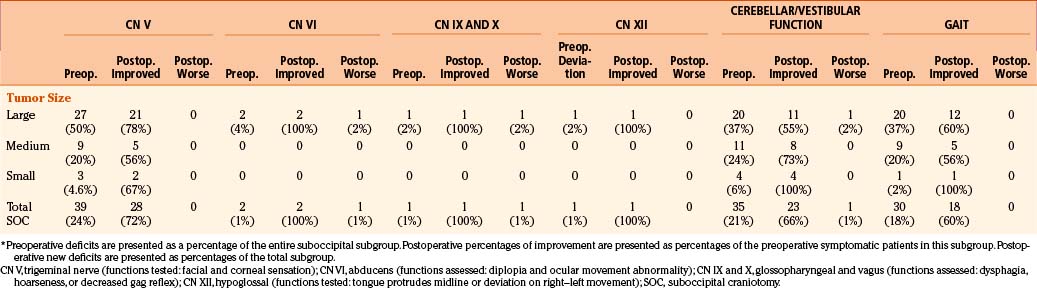

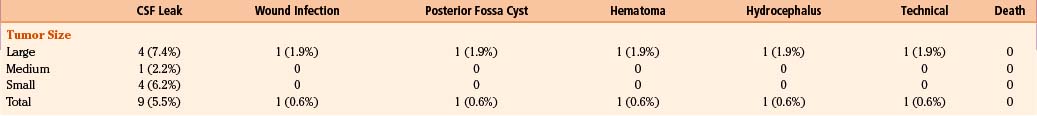

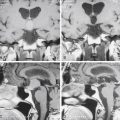

Facial nerve function was determined at multiple time points whenever possible using the House-Brackmann facial nerve outcome scale.10 Tumors were classified as large (more than 3 cm), medium (2.1 to 3 cm), and small (no more than 2 cm),8 as measured from maximal diameter on MRI or CT image. Neurologic function of cranial nerves V, VI, IX, X, and XII; cerebellar function; and gait were assessed. The postoperative improvement is reported as a percentage of preoperative symptomatic patients who experienced improvement or resolution of their symptoms. Postoperative complications are reported as a percentage of that patient subgroup, as categorized by tumor size.

Intraoperative Monitoring Technologies

Hearing Assessment

In both centers, BAERs were measured in response to click stimuli to the ipsilateral ear. In center 1 only, the response to clicks of the auditory nerve was also measured via electrocochleogram (EcochG) using a transtympanic needle electrode resting in the bony prominence or, more recently, an extratympanic electrode (a cotton wick) resting on the exterior surface of the tympanic membrane.9 The standard methodology is to apply clicks to the ipsilateral ear via a special earphone (tube insert) and a low-level (60 dB typically) white noise via a similar earphone to the contralateral ear. Responses to the click stimuli are added, averaged, and noted in the BAER. If EcochG is available, the primary response (N1) corresponding to the auditory significance is the amplitude and latency of wave V in the BAER if present and the amplitude of N1 in the EcochG. Irreversible loss of N1 is often associated with an irreversible postoperative hearing loss (deafness). The status of wave V in the BAER is not perfect in predicting hearing status but we have found that if it is unchanged at the end of surgery, hearing is usually good.

Hearing Preservation

Hearing preservation was analyzed in patients who underwent the suboccipital approach for large, medium, and small tumors. Tumor size was negatively correlated with postoperative hearing preservation (p ≤ 0.003) (Table 45-1). Preoperative hearing class was positively correlated with postoperative hearing preservation (p ≤ 0.001). Important to the patient in situations of daily living is preservation of hearing with 40% or greater speech discrimination (H1 to H3). Patients with medium and small tumors who presented with preoperative hearing ranging from class H1 to class H3 and were operated on by the suboccipital approach had a 6/13 (46%) and 31/38 (82%) chance, respectively, that their hearing would be maintained within hearing classes H1 to H3. Comparison of patients with small tumors and preoperative hearing ranging from class H1 to class H3 who were operated on by the suboccipital approach revealed no difference in hearing preservation between center 1 (11/13 = 85%) and center 2 (20/24 = 83%). In evaluable patients with small tumors operated on with the middle fossa approach (n = 9) during this same period, 78% had hearing preservation, which was not statistically different from the result of small tumors using the suboccipital approach (82%). However, all “small” tumors operated by the middle fossa approach were strictly intrameatal tumors, whereas those operated by the suboccipital approach included larger tumors up to a maximal diameter of 2 cm.

Facial Nerve Preservation

Of the 164 patients operated by the suboccipital route, tumor size was negatively correlated with favorable facial nerve outcome or positively correlated with House-Brackmann facial nerve grade; that is, large tumors were associated with worse House-Brackmann grades immediately postoperatively (p ≤ 0.04), at 2 to 3 months postoperatively (p ≤ 0.02), and at 2 to 3 years postoperatively (p ≤ 0.02). The impact of size of the vestibular schwannoma on facial nerve preservation employing the suboccipital approach assessed at three time points is seen in Table 45-1. In general, with a smaller tumor size, the facial nerve outcome is better.

Difference in Facial Nerve Outcomes between Vestibular Schwannomas Operated on at the Two Centers Using Differing Facial Monitoring Techniques

Facial nerve outcomes for patients who underwent unilateral vestibular schwannoma surgery via the suboccipital approach by me were assessed at various time points. Compared to patients with large tumors operated on at center 2, a significantly higher proportion of patients with large tumors operated on at center 1 had grade I facial nerve outcomes immediately postoperatively (50% vs. 31%) (p = 0.03), 2 to 3 months postoperatively (55% vs. 35%) (p = 0.02), and 2 to 3 years postoperatively (77% vs. 53%) (p = 0.01). A higher proportion of patients with medium-sized tumors operated on at center 1 had grade I facial nerve outcomes at 2 to 3 years postoperatively compared to patients with medium-sized tumors operated on at center 2 (93% vs. 73%) (p = 0.03). For small tumors, there was no significant difference in facial nerve outcome at any time point between the two centers.

Outcomes for Cranial Nerves, Cerebellar Function, and Gait following Vestibular Schwannoma Surgery

Outcomes for cranial nerves V, VI, IX, X, and XII; cerebellar function; and gait were assessed following vestibular schwannoma surgery, as demonstrated in Table 45-2. In patients operated on by the suboccipital approach, preoperative trigeminal nerve symptoms of decreased facial and corneal sensation were most frequent among patients with large tumors. Postoperative resolution of symptoms was observed in the majority of patients. Diplopia from abducens nerve dysfunction (diplopia) was observed preoperatively in two patients with large tumors, and these resolved following surgery. However, one patient with a large tumor and normal preoperative abducens nerve function developed diplopia postoperatively. Lower cranial nerve dysfunction as manifested by decreased gag reflex and dysphagia was observed preoperatively in one patient harboring a large tumor, and this resolved following resection via the suboccipital approach. One patient with a large tumor and normal preoperative lower cranial nerve function developed postoperative symptoms. Hypoglossal nerve dysfunction manifested by tongue deviation was also observed in only one patient preoperatively who harbored a large tumor, and this resolved postoperatively following resection via the suboccipital route.

Other Complications

Overall, as noted in Table 45-3, the incidence of postoperative CSF leak for patients who underwent the suboccipital approach was 5.5% (large tumors 7.4%, medium tumors 2.2%, and small tumors 6.2%). Of the patients who underwent the suboccipital approach and developed CSF leaks, only one patient required repeat surgery with obliteration of the mastoid air cells with an adipose graft; the rest of the patients were treated with lumbar subarachnoid drains, which led to resolution of the leak.

Conclusions

We are now in an era where multiple alternatives for the treatment of vestibular schwannomas exist. These include three surgical approaches, fractionated radiotherapy, and three single-fraction radiosurgery techniques (gamma knife, linear accelerator, and proton beam). If surgery is the chosen method of treatment, the operative approach should be dictated by tumor size and location and the preoperative hearing status of patients. I have used the suboccipital approach for large and medium-sized tumors and even for small tumors in patients with preserved hearing. I considered the translabyrinthine approach for certain medium and small tumors in patients with loss of hearing. Some surgeons use the translabyrinthine approach even for large tumors when hearing is absent. However, I feel there are several benefits to employing the suboccipital approach: it affords the ability to remove a tumor of any size, to preserve cranial nerve function, and to better visualize the brain stem and its vascular supply. I find that the middle fossa approach is best suited when hearing preservation is desired and the tumor is strictly intracanalicular, especially for those with lateral extension.

Hearing preservation is inversely related to tumor size1,4,8,11–19 and is most likely in patients with small tumors (less than or equal to 2 cm) and with good preoperative hearing. I have found no statistical difference in hearing preservation whether or not an EcochG is used. Therefore, I currently use only a BAER and no longer use a transtympanic electrode.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Saad A. Khan, MD, and Asad Khan, PhD, for their help with preparation of the data used in this manuscript and Joseph B. Nadol, MD, and Michael J. McKenna, MD, for their assistance with some surgical procedures and the development of some surgical concepts and monitoring techniques. The author particularly thanks Robert G. Ojemann20 for his initial instruction in these operative techniques.

Arriaga M.A., Chen D.A., Fukushima T. Individualizing hearing preservation in acoustic neuroma surgery. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:1043-1047.

Delgado T.E., Bucheit W.A., Rosenholtz H.R., Chrissian S. Intraoperative monitoring of facial muscle evoked responses obtained by intracranial stimulation of the facial nerve: a more accurate technique for facial nerve dissection. Neurosurgery. 1979;4(5):418-421.

Ebersold M.J., Harner S.G., Beatty C.W. Current results of the retrosigmoid approach to acoustic neurinoma. J Neurosurg. 1992;76(6):901-909.

Fischer G., Fischer C., Remond J. Hearing preservation in acoustic neuroma surgery. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:910-917.

Gardner G., Robertson J.H. Hearing preservation in unilateral acoustic neuroma surgery. Annals of Otology. Rhinology & Laryngology. 1988;97(1):55-66.

House J.W. Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery. 1985;93(2):146-147.

Levine R.A., Ronner S.F., Ojemann R.G. Auditory evoked potentials and other neurophysiological monitoring techniques during tumor surgery in the cerebellopontine angle. In: Lotus C.M., Traynelis V.C. Intraoperative Monitoring Technique During Tumor Surgery in the Cerebellopontine Angle. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994:175-192.

Moffat D.A., da Cruz M.J., Baguley D.M. Hearing preservation in solitary vestibular schwannoma surgery using the retrosigmoid approach. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;121(6):781-788.

Nadol J.B.Jr., Chiong C.M., Ojemann R.G., et al. Preservation of hearing and facial nerve function in resection of acoustic neuroma. Laryngoscope. 1992;102(10):1153-1158.

Ojemann R.G. Management of acoustic neuromas (vestibular schwannomas). Clinical Neurosurgery. 1993;40:498-535.

Ojemann R.G., Martuza R.L.. Acoustic neuroma, Youmans J., editor. Neurological Surgery, 3rd ed., Philadelphia. Ch: WB Saunders Co., 1990. 113: 3316-3350

Rand A.W., Kurze T. Facial nerve preservation by posterior fossa transmeatal microdissection in total removal of acoustic neuroma. J Neurolo Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1965;28:311-316.

Rhoton A.L.Jr. Microsurgical removal of acoustic neuromas. Surgical Neurology. 1976;6(4):211-219.

Samii M. Microneurosurgery of acoustic neuromas with emphasis on preservation of seventh and eighth nerves and scope of facial nerve grafting. In: Rand R.W., editor. Microsurgery. St. Louis: CV. Mosby Co.; 1985:366-388.

Samii M., Matthies C. Management of 1000 vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas): the facial nerve—preservation and restitution of function. Neurosurg. 1997;40(4):684-694.

Samii M., Matthies C. Management of 1000 vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas): hearing function in 1000 tumor resections. Neurosurg. 1997;40(2):248-260.

Sampath P., Holliday M.J., Brem H. Facial nerve injury in acoustic neuroma (vestibular schwannoma) surgery: etiology and prevention. J Neurosurg. 1997;87(1):60-66.

Sterkers J.M., Morrison G.A., Sterkers O., El-Dine M.M. Preservation of facial, cochlear, and other nerve functions in acoustic neuroma treatment. Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery. 1994;110(2):146-155.

Strauss C., Fahlbusch R., Berg M., Haid T. Function saving microsurgery in suboccipital removal of large acoustic neuromas. HNO. 1989;37(7):281-286. [German]

Tatagiba M., Samii M., Matthies C. The significance for postoperative hearing of preserving the labyrinth in acoustic neurinoma surgery. J Neurosurg. 1992;77(5):677-684.

Wiegand D.A., Fickel V. Acoustic neuroma—the patient’s perspective: subjective assessment of symptoms, diagnosis, therapy, and outcome in 541 patients. Laryngoscope. 1989;99(2):179-187.

1. Nadol J.B.Jr., Chiong C.M., Ojemann R.G., et al. Preservation of hearing and facial nerve function in resection of acoustic neuroma. Laryngoscope. 1992;102(10):1153-1158.

2. Ojemann R.G. Management of acoustic neuromas (vestibular schwannomas). Clinical Neurosurgery. 1993;40:498-535.

3. Sampath P., Holliday M.J., Brem H., Niparko J.K., Long D.M. Facial nerve injury in acoustic neuroma (vestibular schwannoma) surgery: etiology and prevention. J Neurosurg. 1997;87(1):60-66.

4. Samii M., Matthies C. Management of 1000 vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas): the facial nerve—preservation and restitution of function. Neurosurg. 1997;40(4):684-694.

5. Samii M., Matthies C. Management of 1000 vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas): hearing function in 1000 tumor resections. Neurosurg. 1997;40(2):248-260.

6. Sterkers J.M., Morrison G.A., Sterkers O., El-Dine M.M. Preservation of facial, cochlear, and other nerve functions in acoustic neuroma treatment. Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery. 1994;110(2):146-155.

7. Wiegand D.A., Fickel V. Acoustic neuroma—the patient’s perspective: subjective assessment of symptoms, diagnosis, therapy, and outcome in 541 patients. Laryngoscope. 1989;99(2):179-187.

8. Samii M. Microneurosurgery of acoustic neuromas with emphasis on preservation of seventh and eighth nerves and scope of facial nerve grafting. In: Rand R.W., editor. Microsurgery. St. Louis: CV. Mosby Co; 1985:366-388.

9. Levine R.A., Ronner S.F., Ojemann R.G. Auditory evoked potentials and other neurophysiological monitoring techniques during tumor surgery in the cerebellopontine angle. In: Lotus C.M., Traynelis V.C. Intraoperative Monitoring Technique During Tumor Surgery in the Cerebellopontine Angle. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994:175-192.

10. House J.W., Brackmann D.E. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery. 1985;93(2):146-147.

11. Rhoton A.L.Jr. Microsurgical removal of acoustic neuromas. Surgical Neurology. 1976;6(4):211-219.

12. Delgado T.E., Bucheit W.A., Rosenholtz H.R., Chrissian S. Intraoperative monitoring of facial muscle evoked responses obtained by intracranial stimulation of the facial nerve: a more accurate technique for facial nerve dissection. Neurosurgery. 1979;4(5):418-421.

13. Ebersold M.J., Harner S.G., Beatty C.W. Current results of the retrosigmoid approach to acoustic neurinoma. J Neurosurg. 1992;76(6):901-909.

14. Gardner G., Robertson J.H. Hearing preservation in unilateral acoustic neuroma surgery. Annals of Otology. Rhinology & Laryngology. 1988;97(1):55-66.

15. Tatagiba M., Samii M., Matthies C. The significance for postoperative hearing of preserving the labyrinth in acoustic neurinoma surgery. J Neurosurg. 1992;77(5):677-684.

16. Arriaga M.A., Chen D.A., Fukushima T. Individualizing hearing preservation in acoustic neuroma surgery. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:1043-1047.

17. Fischer G., Fischer C., Remond J. Hearing preservation in acoustic neuroma surgery. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:910-917.

18. Moffat D.A., da Cruz M.J., Baguley D.M. Hearing preservation in solitary vestibular schwannoma surgery using the retrosigmoid approach. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;121(6):781-788.

19. Strauss C., Fahlbusch R., Berg M., Haid T. Function saving microsurgery in suboccipital removal of large acoustic neuromas. HNO. 1989;37(7):281-286. [German]

20. Ojemann R.G., Martuza R.L.. Acoustic neuroma, Youmans J., editor. Neurological Surgery, 3rd ed., Philadelphia. Ch: WB Saunders Co., 1990. 113: 3316-3350