Stroke III

Investigations

Investigations are directed at answering the following questions:

Is it a stroke? What kind of stroke is it?

Making the diagnosis of stroke on the basis of the history, either from the patient or a relative, and the examination is usually straightforward. The differential diagnosis that needs to be considered has been discussed previously (Box 1, p. 67). The clinical classification is considered on page 66. Haemorrhagic and ischaemic strokes cannot be reliably distinguished clinically.

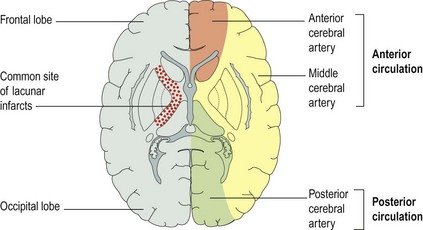

The diagnosis of stroke can be confirmed by CT or MRI scanning, which will indicate whether the stroke is haemorrhagic. Early CT scans can be normal, indicating that the stroke is ischaemic and not haemorrhagic. MRI diffusion weighted images (DWI) can be used to distinguish new from old ischaemic lesions. The distribution of any abnormality will indicate the affected vascular territory (Fig. 1).

CT and MRI scans are recommended though are not yet performed in all patients.

Why did the stroke occur?

The likely aetiology of an ischaemic stroke can usually be determined from the history and examination. The range of investigations that may be used is given in Box 1.

Treatment and prognosis

Treatment

The treatment of patients with strokes aims to:

General medical support of the patient

Initially the patient with a large stroke may need to be resuscitated with protection of the airway, making them nil by mouth and giving nasogastric or parenteral fluids. Most patients will need assessment of their swallowing to determine whether it is safe for them to have oral fluids. In managing the fluid balance, it is best to keep the patient slightly underhydrated for the first week to minimize cerebral oedema.

Hypoxia, hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia should be treated.

Minimize stroke size

Thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rTPA) decreases ischaemic stroke size and improves outcome if given within 3 h of stroke onset. Prior to treatment, a CT scan needs to be performed to exclude haemorrhage or significant cerebral damage, which could be transformed into fatal haemorrhage by rTPA. This is currently only possible for a minority of patients with stroke who are present very early and who have no other contraindication (Box 2). Aspirin also reduces 30-day stroke mortality.

Prognosis

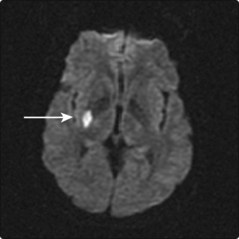

The outcome after a stroke depends primarily on the type of stroke and the clinical stroke syndrome. Primary intracranial haemorrhage carries a 50% mortality, with 50% of survivors dependent at 6 months. Total anterior circulation ischaemic strokes have a similar mortality but a higher (90%) level of dependent patients at 6 months. Partial anterior circulation strokes, lacunar strokes (Fig. 2) and posterior circulation strokes have a 10–15% mortality with 20–40% of survivors dependent at 6 months. Ischaemic heart disease is the most common cause of death following a stroke or TIA.