Stroke II

Clinical features

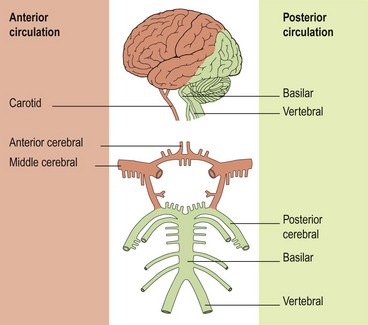

The clinical manifestations of stroke depend on the area of the brain affected, which in turn depends on which blood vessel is affected. The anatomy of the blood vessels supplying the brain can be subdivided according to vessel size (large or small) and vessel site (anterior or posterior) (Fig. 1):

Anterior circulation:

Anterior circulation:

Posterior circulation:

Posterior circulation:

The anterior circulation supplies the anterior two-thirds of the cerebrum, while the posterior circulation provides the supply for the occipital lobes of the cerebrum and the brain stem and cerebellum (Fig. 1).

Anterior circulation large vessel strokes

Partial anterior circulation stroke

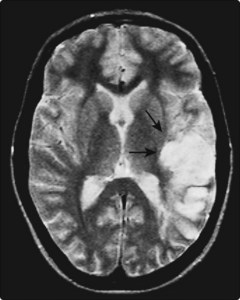

Infarction in the territory of one of the branches of the MCA produces different combinations of deficits depending on the affected hemisphere (Fig. 2). Some of the common ones are: inferior branch = hemianopia – Wernicke’s aphasia if dominant, or constructional apraxia if non-dominant; superior branch = hemiparesis – Broca’s aphasia if dominant or neglect if non-dominant. Distal branches lead to cortical infarcts with weakness only of one limb or isolated higher function deficits.

Posterior circulation strokes (Fig. 3)

Other posterior circulation strokes

A large number of clinical syndromes (often eponymous) have been described arising from posterior circulation strokes. Cerebellar signs are commonly seen, indicating damage to the cerebellum or its connections. Nystagmus, dysarthria and diplopia are features that point to a brain stem lesion. A feature in this, and other brain stem diseases, is the crossed cranial nerve and long tract sensory or motor deficit. For example, the lateral medullary syndrome (the site of the lesion is the lateral medulla) comprises: lesions to the brain stem nuclei and cerebellar connections which produce ipsilateral facial sensory loss; Horner’s syndrome; vocal cord paralysis and cerebellar ataxia; and damage to the spinothalamic tract which results in contralateral loss of pinprick and temperature sensation in the limbs.

In addition, brain stem events can result in lacunar syndromes.

Small vessel lacunar strokes

Pure motor hemiparesis: face, arm and leg weakness with no other deficits. Usually an internal capsule lesion.

Pure motor hemiparesis: face, arm and leg weakness with no other deficits. Usually an internal capsule lesion. Ataxic hemiparesis: motor hemiparesis with cerebellar type ataxia on that side. Lesion site is variable: posterior internal capsule, midbrain or pons.

Ataxic hemiparesis: motor hemiparesis with cerebellar type ataxia on that side. Lesion site is variable: posterior internal capsule, midbrain or pons.Differential diagnosis

The diagnosis of stroke is usually straightforward (Box 1). Space-occupying lesions (SOLs) are usually more insidious in onset than stroke, though some tumours can present with a ‘vascular’ onset, particularly if there is bleeding into a tumour. Cerebral abscesses have a more rapid progression than most SOLs but the patient is usually unwell and septic. Chronic subdural haematoma is a very important diagnosis to consider because of the need for neurosurgical intervention. The onset is usually slower and very often the patient is mentally slower, as well as exhibiting focal deficits, and there may be signs of raised intracranial pressure.