36 Stridor

Etiology and Pathogenesis

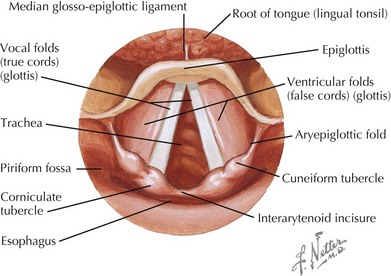

Stridor can be caused by any upper airway obstruction. When thinking about the causes of stridor, it is helpful to first understand the anatomy of the larynx (Figure 36-1) and then to separate the causes of stridor into chronic and acute processes.

Acute Stridor

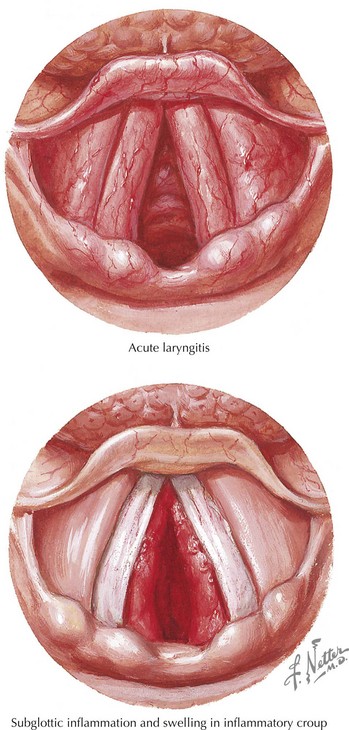

The causes of acute stridor are primarily infectious in cause with two notable exceptions, foreign body aspiration and allergic reaction. The most common cause of acute stridor is laryngotracheobronchitis, or croup (Figure 36-2). Croup is classically caused by parainfluenza virus but can also be caused by respiratory syncytial virus, influenza, adenovirus, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Bacterial tracheitis, usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus, is an uncommon but life-threatening condition that occurs most frequently as a bacterial superinfection in patients who have viral croup.

Clinical Presentation

Acute Stridor

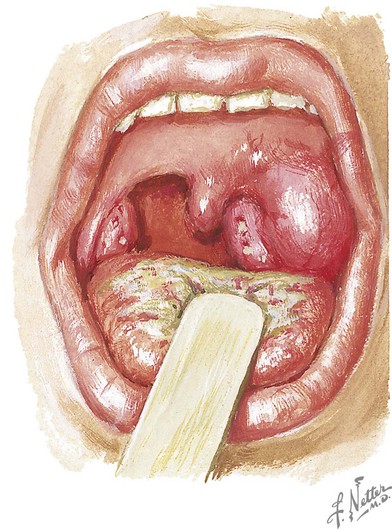

Retropharyngeal abscess usually occurs in children younger than 6 years old before the retropharyngeal lymph nodes atrophy. Patients often have a viral prodome followed by the abrupt onset of high fever, limited neck movement (especially resistance to extension), and occasionally stridor. Unilateral neck swelling may occur as the infection tracks from the retropharyngeal space, and a bulge of the posterior oropharynx may sometimes be present on physical examination. Peritonsillar abscess occurs in preadolescents and adolescents and can present with sore throat, trismus, dysphagia, a “hot potato” or muffled voice, and tender unilateral neck swelling. Asymmetric tonsils, deviation of the uvula, and a fluctuant area are present on physical examination (Figure 36-3). Stridor may be heard if tracheal compression is present. Epiglottitis classically presents with the abrupt onset of high fever, stridor, drooling, “tripod” positioning, and toxicity.

Evaluation and Management

Evaluation

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the neck and chest will allow evaluation of both the upper and lower airways and may be indicated for specific diagnoses. Other imaging modalities such as contrast-enhanced computed tomography and fluoroscopy may also be used. Further imaging may be indicated for specific cases (Table 36-1).

| Cause of Stridor | Diagnostic Imaging |

|---|---|

| Laryngomalacia | DL will show inspiratory collapse of the epiglottis. Redundant arytenoids may be present. DL is also the test of choice for diagnosing laryngeal webs, cysts, and subglottic hemangiomas. |

| Subglottic stenosis | DL or bronchoscopy |

| Tracheomalacia | Airway fluoroscopy or bronchoscopy. Barium swallow to determine the presence of coexisting conditions. |

| Vascular ring | Barium swallow may show an indentation on the esophagus. Echocardiography is often diagnostic. |

| Croup | Usually a clinical diagnosis. Lateral neck radiograph, if obtained, demonstrates normal epiglottis but with subglottic narrowing (steeple sign). |

| Epiglottitis | Lateral neck radiograph demonstrates edematous epiglottis (thumb sign) |

| Retropharyngeal abscess | Lateral neck radiograph shows widening of the prevertebral soft tissues to greater than half the width of the adjacent vertebral body. |

| Peritonsillar abscess | Usually a clinical diagnosis. Contrast-enhanced CT scan of the neck may delineate abscess versus phlegmon and degree of airway impingement. |

| Foreign body aspiration | Lateral neck or chest radiograph may show the foreign body if radiopaque. Inspiratory and forced expiratory or lateral decubitus chest radiographs may demonstrate hyperinflation and air trapping on the affected side. Bronchoscopy is often required for definitive diagnosis. |

CT, computed tomography; DL, direct laryngoscopy.

Management

The bacterial infectious causes of stridor all require antibiotics (Table 36-2). Peritonsillar and retropharyngeal abscesses often require drainage as well because antibiotic penetration of the abscess may not be optimal. Epiglottitis is an entity that should be considered a medical emergency necessitating immediate intubation for airway protection.

| Infectious Causes of Stridor | Empiric Antibiotic Therapy |

|---|---|

| Epiglottitis | Ceftriaxone |

| Retropharyngeal abscess | Clindamycin or ampicillin–sulbactam |

| Peritonsillar abscess | Clindamycin or ampicillin–sulbactam |

| Bacterial tracheitis | Vancomycin or clindamycin |

Bjornson CL, Klassen TP, Williamson J, et al. A randomized trial of a single dose of oral dexamethasone for mild croup. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1306-1313.

Craig FW, Schunk JE. Retropharyngeal abscess in children: clinical presentation, utility of imaging, and current management. Pediatrics. 2003;111(6 Pt 1):1394-1398.

Masters IB. Congenital airway lesions and lung disease. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56(1):227-242. xii

Sampson HA, Muñoz-Furlong A, Campbell RL, et al. Second symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: summary report—Second National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network symposium. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(2):391-397.