Chapter 42 STRIDOR

General Discussion

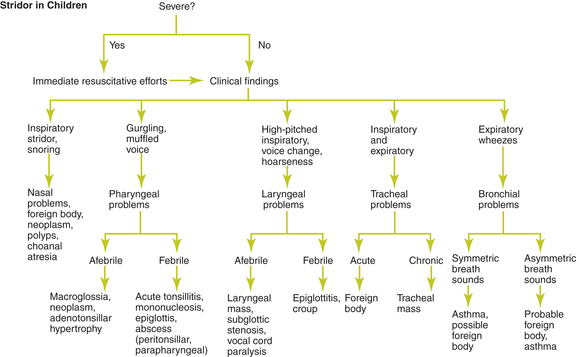

Anatomically, stridor is a phenomenon caused by narrowing of the upper airway. The upper airway may be divided into supraglottic, glottic and subglottic, and intrathoracic areas. These anatomic distinctions are essential in targeting the possible causes of stridor (Figure 42-1). The supraglottic area includes the nasopharynx, epiglottis, larynx, aryepiglottic folds, and false vocal cords. The glottic and subglottic area extends from the vocal cords to the extrathoracic portion of the trachea.

Figure 42-1 Algorithm, based on clinical findings, for evaluating stridor in children.

(Adapted with permission from Handler SD. Stridor. In: Fleisher GR, Ludwig S, eds. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1993:474–478.)

If a bacterial cause is suspected, rapid and decisive action must be taken.

Causes of Stridor

Supraglottic area

• Gastroesophageal reflux disease

• Hypertrophic tonsils and adenoids

• Intubation (resulting in vocal cord paralysis, laryngotracheal stenosis, subglottic edema, or laryngospasm)

• Laryngospasm (hypocalcemic tetany)

Glottic and Subglottic Area

Key Historical Features

Key Physical Findings

Vital signs, with attention to fever, heart rate, and respiratory rate

Vital signs, with attention to fever, heart rate, and respiratory rate

Measurement of height and weight

Measurement of height and weight

Assessment of potential for impending airway obstruction

Assessment of potential for impending airway obstruction

General evaluation for evidence of toxicity, cyanosis, respiratory distress, or drooling

General evaluation for evidence of toxicity, cyanosis, respiratory distress, or drooling

Head and neck examination for craniofacial malformation or abnormalities in the size of the tongue or mandible. Examination of the pharynx and soft tissues of the neck for neck edema, lymphadenopathy, or evidence of peritonsillar abscess or pharyngitis. Note any surgical scars on the neck or upper chest.

Head and neck examination for craniofacial malformation or abnormalities in the size of the tongue or mandible. Examination of the pharynx and soft tissues of the neck for neck edema, lymphadenopathy, or evidence of peritonsillar abscess or pharyngitis. Note any surgical scars on the neck or upper chest.

Observation of the nature and timing of the stridor (inspiratory, expiratory, or biphasic). Note the positioning of the patient and the use of accessory muscles. Note whether the stridor improves when the child is prone.

Observation of the nature and timing of the stridor (inspiratory, expiratory, or biphasic). Note the positioning of the patient and the use of accessory muscles. Note whether the stridor improves when the child is prone.

Auscultation of the mouth and neck to determine the origin of the stridor

Auscultation of the mouth and neck to determine the origin of the stridor

Auscultation of the lungs for evidence of abnormal breath sounds

Auscultation of the lungs for evidence of abnormal breath sounds

Cardiac examination for murmurs

Cardiac examination for murmurs

Suggested Work-up

| Complete blood count (CBC) | May be helpful in determining whether an infectious cause is present |

| Neck radiographs | May reveal changes associated with retropharyngeal abscess (soft tissue air-fluid levels, cervical retroflexion, retropharyngeal space greater than 7 mm anterior to the inferior border of the second cervical vertebral body), croup (“steeple” sign), epiglottitis (thumb sign and a ballooned hypopharyngeal airway), or foreign body (if radio-opaque) |

Additional Work-up

| Chest radiographs | If an intrathoracic etiology is suspected |

| Viral serologies | May be used for confirmatory testing for suspected parainfluenza, influenza A and B, and respiratory syncitial virus infections |

| Blood cultures | Should be considered in cases of peritonsillar or retropharyngeal abscess |

| Computed tomography (CT) scan of the neck and chest | May be helpful in diagnosing retropharyngeal abscess and for looking for enlarged lymph nodes, tumor, aberrant arteries, and vascular rings |

| Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) | Can be useful in evaluating the trachea and the mediastinum |

| Airway fluoroscopy | If tracheomalacia is suspected |

| Barium swallow | May help to identify esophageal abnormalities, GERD, swallowing dysfunction, mediastinal masses, and vascular rings |

| Gastrograffin swallow | Used instead of barium swallow if tracheoesophageal fistula is suspected |

| Spirometry | In children older than 6 years, spirometry may be used to help distinguish the site of the obstruction and its response to bronchodilators |

1. Clark J. The wheezing child. Clin Pediatr. 2008;47(2):191–198.

2. Friedberg J. An approach to stridor in infants and children. J Otolaryngol. 1987;16:203–206.

3. Handler S.D. Stridor. In: Fleisher G.R., Ludwig S., editors. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1993:474–478.

4. Leung A.K.C., Cho H. Diagnosis of stridor in children. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60:2289.

5. Mancuso R.F. Stridor in neonates. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1996;43:1339–1356.

6. Nicklaus P.J., Kelley P.E. Management of deep neck infection. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1996;43(6):1277–1296.

7. Simon N.P. Evaluation and management of stridor in the newborn. Clin Pediatr. 1991;30:211–216.