29

Strategies to improve global maternal and neonatal health

Estimates of global maternal and neonatal mortality

Obstetric causes of maternal mortality

Medical conditions contributing to maternal mortality and morbidity

Estimates of global maternal and neonatal mortality

It is estimated that almost 300 000 women worldwide die each year from the complications of pregnancy and childbirth, with 99% of these occurring in developing countries. Estimates from 2010 by the World Health Organization (WHO) and other partners, show that just over half of all maternal deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa alone and about one-third of all maternal deaths occur in South Asia. For every woman who dies, around 20 women have serious ill-health and lifelong disability as a result of these same complications.

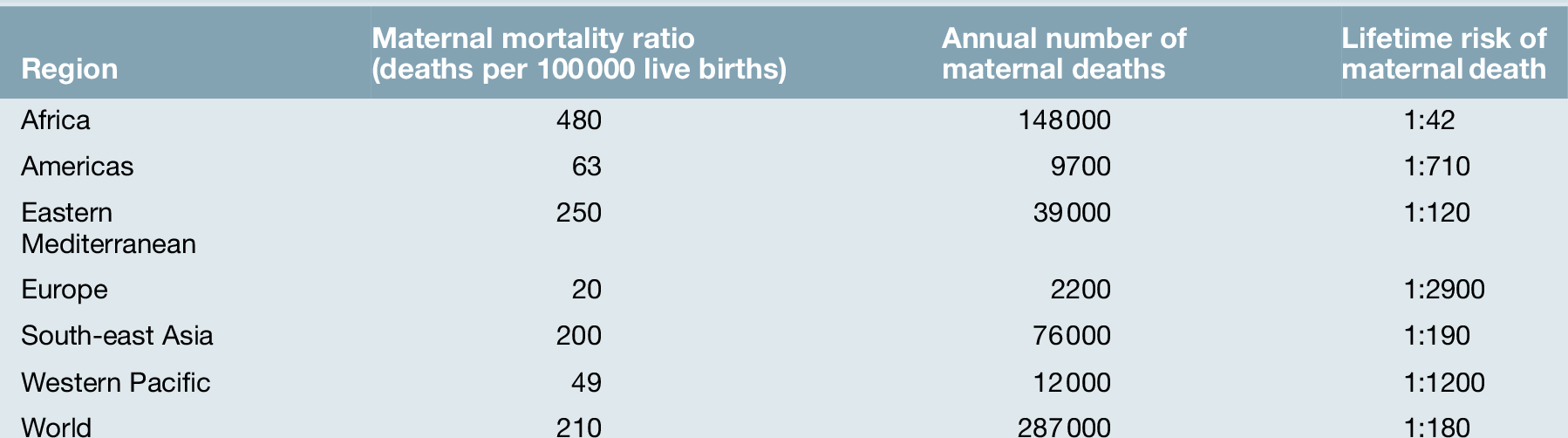

Eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were adopted in 2000 following the Millennium Summit, two of which are directly related to maternal and newborn health: MDG 4 to reduce child mortality, and MDG 5, which sets a target of reducing maternal mortality by 75% between 1990 and 2015. Although the latest estimates of maternal deaths published in 2011 suggest a decline in maternal mortality since 1990, there is lack of progress in a number of developing countries especially in sub-Saharan Africa and South-east Asia (Table 29.1).

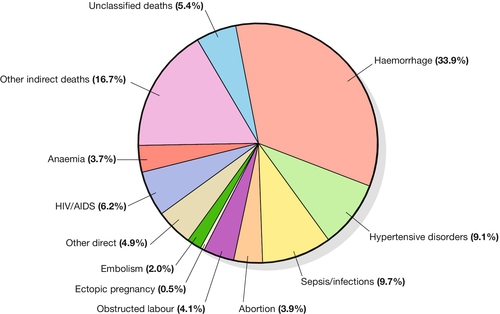

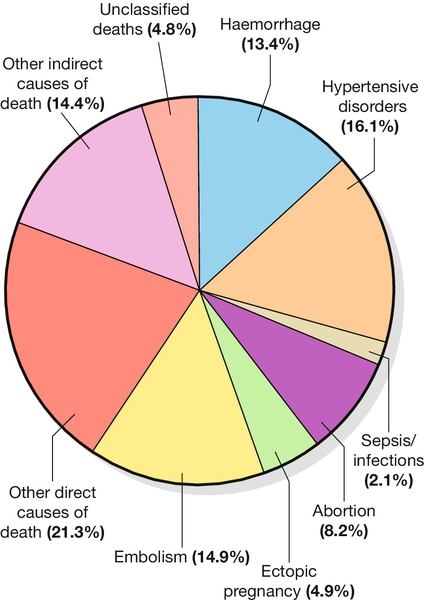

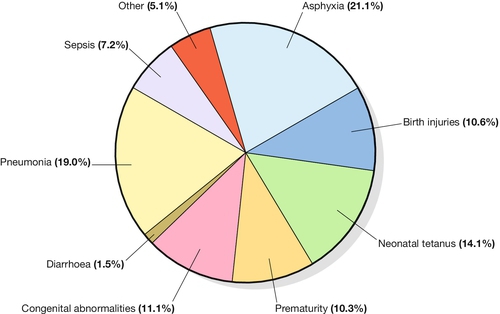

At least 80% of all maternal deaths globally result from five complications that are well understood and can be readily treated: haemorrhage, sepsis, eclampsia, complications of obstructed labour and abortion. This is in contrast to cause of death in more developed countries where maternal deaths are more likely to be due to indirect causes (Figs 29.1 and 29.2). In addition to this high number of maternal deaths, an estimated 4 million neonatal deaths and 3 million stillbirths occur each year. Neonatal deaths account for at least 40% of all deaths of children under 5 years of age. MDG 4 is to reduce the under-5 mortality rate by two-thirds between 1990 and 2015. Progress on reducing child mortality has also been substantially slower than the annual target rate of decline for children, although more progress has been made compared to maternal mortality. The health of the neonate is closely related to that of the mother, and the majority of deaths in the first month of life could also be prevented if interventions were in place to ensure good maternal health (Fig. 29.3). Birth injuries, birth asphyxia and most neonatal tetanus could be prevented with skilled professional care at the time of the delivery as well as in antenatal and postnatal periods. Similarly, many cases of sepsis in the neonate are directly linked to the health of the mother and/or the care she received during childbirth. It is estimated that one-third of all stillbirths occur during labour and delivery.

Obstetric causes of maternal mortality

The five main causes of direct obstetric maternal mortality are discussed here.

Haemorrhage

Many maternal deaths in resource-poor areas are caused by or associated with haemorrhage. This may be because of antepartum bleeding (e.g. abruption of the placenta), bleeding during delivery (e.g. with a ruptured uterus or placenta praevia) or postpartum (e.g. from an atonic uterus or retained placenta).

The risk of dying from haemorrhage is higher if women are already anaemic in pregnancy (Hb < 11.0 g/dL). Oxytocics are very effective in preventing postpartum haemorrhage (active management of the third stage), as well as in treating uterine atony, but oxytocics may not be routinely used and/or available. Manual removal of a retained placenta can be carried out by trained midwives and doctors using simple general anaesthesia (e.g. with IM ketamine). The ability to give intravenous fluids, safe blood transfusion and anaesthesia is extremely important when pregnancy or delivery is complicated by haemorrhage. It is estimated that non-availability of blood for transfusion accounts for about a quarter of deaths associated with haemorrhage.

Obstructed labour

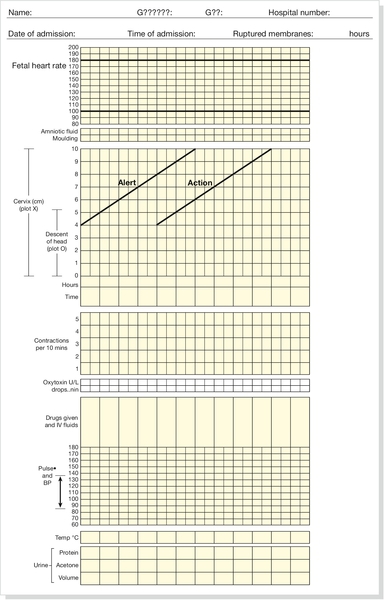

Most cases of maternal death associated with obstructed labour (see also Chapter 44) are attributable to rupture of the uterus (Fig. 29.4). Persistent malposition, e.g. transverse lie which if unrecognized and allowed to progress is also a cause of rupture of the uterus (Fig. 29.5). The correct use of a simple partogram, with an ‘action line’ to prompt a response if labour does not progress normally, has been shown to be very helpful in making a timely diagnosis of cephalo-pelvic disproportion or simple failure to progress (Fig. 29.6).

Fig. 29.6WHO modified partogram.

The ‘alert’ and ‘action’ lines can be used to prompt referral or intervention if delay in progress of labour is apparent.

In many cases of obstructed labour, women are referred to a health facility late. The presenting part may be deeply impacted in the pelvis and a vaginal examination may demonstrate oedema and overlapping of the fetal skull bones. The mother will be dehydrated, exhausted, in severe pain from a tonically contracted uterus or pyrexial as a result of infection and/or sepsis. If the uterus has ruptured, the fetal heartbeat is usually absent and the fetal parts can usually be palpated easily abdominally. In addition, the woman may be in shock as a result of bleeding or sepsis. Bleeding during delivery should always be a cause for alarm if cephalo-pelvic disproportion is suspected.

A woman with cephalo-pelvic disproportion in labour may also have a Bandl’s ring. This is a visible constriction seen in the abdominal contour, which is a warning sign of impending rupture of the uterus. If the presenting part has been impacted in the pelvis for many hours, pressure necrosis of the genital tract, as it is compressed between the baby’s head and the bony pelvis, may lead to obstetric fistulae. Vesicovaginal fistulae are the most common, but rectovaginal and ureterovaginal fistulae also occur. Such fistulae may also occur after difficult obstetric abdominal surgery. Women who suffer from fistulae often have no living child, they become outcasts from their society, and may live in poverty. Very many women with fistulae are unable to access suitable care.

In order to try to prevent fistulae, or to encourage small fistulae to close spontaneously, it is important that all women who have survived prolonged or obstructed labour (with or without a caesarean section) should be treated initially by continuous bladder drainage and preferably with antibiotics to minimize the risk of urinary tract infection. Spontaneous closure can occur within 6–8 weeks with such conservative management, but most fistulae do not heal spontaneously and require specialized surgical management. Such surgery requires considerable expertise and specialists (obstetrician–gynaecologists and urologists) will need to seek additional training to be able to offer a good surgical repair. Equally important is the provision of good nursing care, physiotherapy and steps towards rehabilitation and reintegration into society for women who have suffered fistulae.

Sepsis

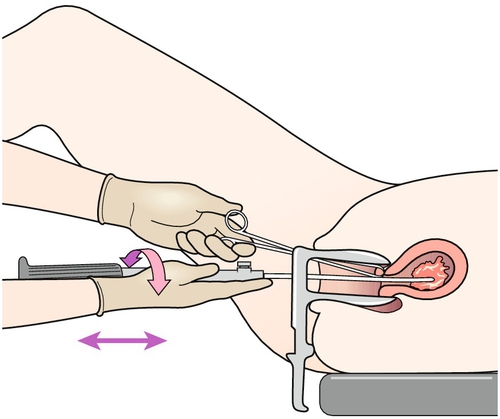

Sepsis following prolonged membrane rupture or retained products of conception (incomplete miscarriage or unsafe abortion) may lead to overwhelming septic shock, multisystem failure and death. Early recognition and prompt commencement of antibiotic treatment is important. If there are retained products of conception, manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) of retained products of conception can be life-saving (Fig. 29.7). This has, in many countries, replaced the traditional technique of dilatation and curettage (D&C), which requires general anaesthesia. Using good technique, MVA can be performed in early pregnancy under local anaesthesia.

Unrecognized rupture of the membranes during pregnancy risks ascending infection and this can lead to chorioamnionitis, premature delivery and major systemic sepsis if not recognized and treated during the antenatal period. Prophylactic antibiotics must always be given after prolonged membrane rupture as well as at the time of a CS.

Untreated sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are common during pregnancy in resource-poor countries and may contribute to sepsis. Similarly, underlying impairment of the overall immune response, for example with HIV infection, carries an increased risk of opportunistic infections and also makes it more difficult to treat sepsis when this occurs.

Eclampsia

Eclampsia, especially if a fit is prolonged, can lead directly to maternal death. As pre-eclampsia and eclampsia are multi-organ diseases, the exact cause of a death can, however, often be difficult to ascertain. Cerebral haemorrhage is probably the most common cause of death, but renal or hepatic failure, respiratory failure, coagulopathy or HELLP syndrome may also contribute.

Recognition of pre-eclampsia by measurement of blood pressure and testing of urine for protein should be available for all women during pregnancy and after delivery. Magnesium sulphate reduces the incidence of seizures in women with severe pre-eclampsia and is the preferred treatment drug for an eclamptic fit. For a woman with pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, delivery is needed urgently; this obviously requires the means to induce labour, or to deliver by caesarean section. Adequate drug control of blood pressure is important to prevent cerebral accidents, and good monitoring in a high-dependency area of the ward of such a sick woman is very useful in preventing and treating further complications which may include pulmonary oedema.

Unsafe abortion

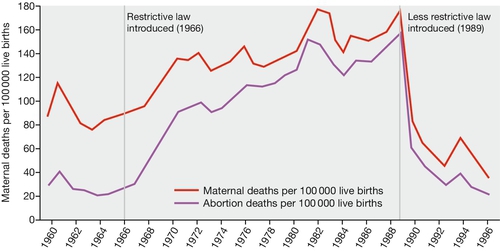

As abortion is illegal in many countries, in Africa, Latin America, the Middle East and many Asian countries, attempts at abortion are often carried out by unskilled practitioners outside the existing medical care system. Unsafe abortion may lead directly to maternal death through uterine perforation, sepsis and haemorrhage. Maternal deaths from abortion are more frequently seen with the non-availability of safe abortion services (Fig. 29.8).

Fig. 29.8The change in the rate of maternal mortality from abortion in Romania (1960–1996).

Unsafe abortion is also strongly linked to the non-availability of contraception.

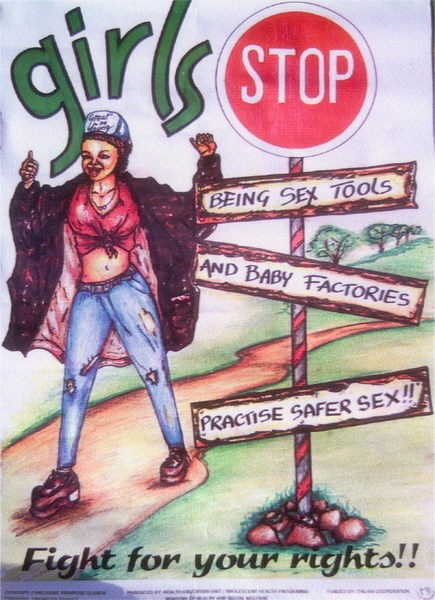

The occurrence of unsafe abortion is strongly linked to the non-availability of contraception. Many women do not have access to a full range of contraceptives and in some instances, they may not be able to use contraceptives without permission from their husbands and/or family in law. Young girls in particular often encounter significant barriers to accessing contraceptives if they are not married or in a recognized and approved relationship (Fig. 29.9).

Medical conditions contributing to maternal mortality and morbidity

In addition to the main direct obstetric causes of death, there are often underlying medical conditions during pregnancy which exacerbate the risk of a complication should this occur. In developing countries, these commonly include anaemia, malaria, HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis.

Anaemia

It has been estimated that over half the pregnant women in the world have a haemoglobin level indicative of anaemia (Hb < 11.0 g/dL). This is usually a chronic anaemia and the mother is frequently asymptomatic at rest, but she may decompensate easily in labour and, in the event of any obstetric haemorrhage, she is much more likely to die.

Relatively few studies have comprehensively assessed the aetiological factors responsible for anaemia in pregnancy, but it is likely that anaemia is a result of multiple factors, which will vary between geographical areas and by season. These factors include malaria, micronutrient deficiency (iron, vitamin A), parasitic infestation, recurrent bleeding in pregnancy, chronic infections and infection with HIV.

Malaria

As well as contributing directly to maternal death in some settings, malaria is most often one of the causes of maternal anaemia and this contributes to maternal deaths indirectly. Malaria should be considered in any pregnant woman presenting with fever in a malaria-prone area. The symptoms and any complications will depend on the intensity of malaria transmission and the level of acquired immunity (higher immunity in areas of moderate or high transmission). Pregnant women with severe malaria are prone to hypoglycaemia, pulmonary oedema, anaemia and cerebral malaria, as well as hypoglycaemia may lead to loss of consciousness.

A thick (blood) film will help detect the parasite, and a thin film will identify the species. Of the four types of human malaria, Plasmodium vivax and P. falciparum are the most common and P. falciparum is the most lethal. Rapid diagnostic tests are increasingly available and used in regions of the world where malaria is endemic. If facilities for testing are not available, empirical treatment should be commenced. Treatment depends on the sensitivity profile of the local species. In countries where malaria is common, all pregnant women are recommended routine prophylaxis during pregnancy, and mother and children should sleep under insecticide treated bed nets.

HIV/AIDS

Worldwide, about 40 million people are living with HIV infection and about half of all affected adults are female. The largest proportion of maternal deaths associated with HIV infection occur in sub-Saharan Africa and the Caribbean.

Women who are HIV-positive have an increased susceptibility to infections and are therefore at higher risk of maternal mortality associated with sepsis. In addition, women may have HIV associated infections such as tuberculosis, cryptococcal pneumonia and meningitis.

Mother-to-child transmission has been by far the most important cause of infection in the estimated 5 million HIV-positive children. Pregnant women should be offered screening for HIV early in pregnancy because appropriate antenatal interventions are needed both to treat the mother and to reduce maternal-to-child transmission of HIV infection. This includes antiretroviral therapy (ARV) for the mother, as well as to prevent transmission. In addition, consideration should be given to delivery by caesarean section and avoidance of breastfeeding where indicated. Choice and type of ARV is dependent on viral load and CD4 count; it is also very important to recognize and treat opportunistic infections, including STIs, tuberculosis and Pneumocystis carinii.

In many countries, being HIV-positive carries a very significant ‘stigma’ and many women (and men) do not undergo testing. Antiretroviral therapy is also still far from widely available in many countries and HIV healthcare services are not always integrated within the antenatal or postnatal care services.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is probably the leading cause of death in women affected by HIV/AIDS. One-third of the world population is infected with TB. Sputum smears will be positive for acid fast bacilli (AFB) in the majority of women with pulmonary disease. This is best examined in a specimen of early morning sputum taken on at least three occasions. A chest X-ray can also be taken (with shielding of the fetus). Treatment involves multiple drug therapy, usually rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide and streptomycin (all except streptomycin are considered safe in pregnancy and with breastfeeding). The risk of untreated TB to the pregnant woman and the fetus far outweighs the risk of treatment. Neonatal TB may be congenital or perinatal. A BCG vaccination is given to all babies born in areas where there is an increased risk of coming into contact with TB.

Strategies to improve global maternal and newborn health

Within the continuum of care for women and their babies, there are two agreed key ‘care packages’ that, if implemented, will reduce maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity:

![]() the provision of skilled birth attendance (SBA)

the provision of skilled birth attendance (SBA)

![]() the availability of essential (or emergency) obstetric care (EOC) and newborn care (NC).

the availability of essential (or emergency) obstetric care (EOC) and newborn care (NC).

Skilled birth attendance

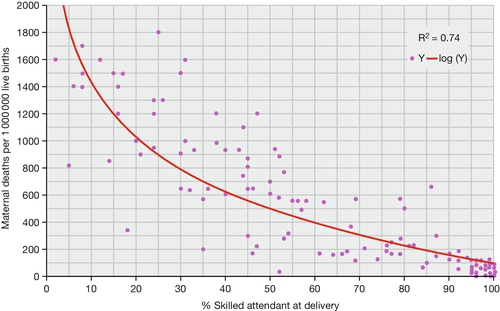

A skilled birth attendant (SBA) is someone with the midwifery skills necessary to manage normal delivery and diagnose, stabilize and refer obstetric complications. Skilled birth attendance is the term used for a skilled birth attendant plus the enabling environment, i.e. the necessary drugs, equipment, transport and supportive healthcare system in which the skilled birth attendant works. Maternal mortality is lowest in those countries where the percentage of women who have a skilled birth attendant at delivery is highest (Fig. 29.10).

At least one-third of all women in developing countries deliver without the help of a skilled birth attendant. Many developing countries aim to rapidly increase the number of skilled health workers. Pre-service curricula may be revised to be more in line with the competencies needed by a skilled birth attendant or may be adopted to provide fast-track midwifery training. For existing healthcare professionals, up-skilling can enable them to provide a wider range of care. A renewed focus on ‘skills and drills’ type competency based in-service training is being encouraged in many developing country settings (Fig. 29.11). Although a variety of healthcare provider cadres are recognized in countries as ‘skilled birth attendants’, research has shown that they may not be competent to confidently provide skilled care at birth by agreed international standards. As there is often a migration of doctors from the poorer rural parts of many countries to the wealthier cities, and a migration of doctors from under-resourced countries to those countries with greater income potential, there is often sense in focusing training on those most likely to remain resident where the need is greatest.

Essential (or emergency) obstetric care

It has been estimated around 15% of all pregnant women will develop a complication which can become life-threatening if good obstetric care is not available to them. The components of care generally needed in such cases have been bundled into a care package called essential (or emergency) obstetric care (EOC). EOC consists of up to nine ‘signal functions’ or components (Box 29.1). To reduce maternal mortality, it is important that all women have access to emergency (or essential) obstetric care (EOC) when an obstetric complication occurs. EOC is commonly divided into basic emergency obstetric care (BEOC) and comprehensive emergency obstetric care (CEOC). The UN agencies recommend that a minimum of five healthcare facilities able to provide EOC should be available for a population of 500 000, at least one health facility should be able to provide CEOC and four should be able to provide BEOC. In many countries, this minimum level of coverage is not yet in place. Designated health facilities should be able to provide EOC 24 hours a day and 7 days a week. The distribution of health facilities must be equitable, so that all women in the population have access to this package of health care, whether they live in rural or urban areas.

The signal functions or components of EOC are relatively inexpensive and require basic obstetric knowledge and skills. In practice, in most developing country settings, nurse-midwives are able to provide BEOC and medical doctors CEOC. There may be many reasons why EOC signal functions may not be available. Magnesium sulphate, which is relatively inexpensive, is not always available at the health facility and/or local healthcare providers may not be familiar with its use. Cheaper broad-spectrum oral antibiotics are generally available, but intravenous antibiotics and other more expensive preparations (which may be needed for drug-resistant strains) may not be available in remote locations. When doctors are not around, the nurse-midwife may not be licensed or permitted to give even a starting dose of parenteral antibiotics, anticonvulsant or commence an intravenous infusion.

Manual vacuum aspiration can be easily carried out with a simply operated hand-pump, but this needs to be purchased, the device maintained, and sufficient numbers of healthcare providers need to be trained in its use.

Blood is almost always in short supply. Many hospitals do not have functioning blood banks and often blood can be given only if a relative or a friend provides it, or replaces any blood already available at the health facility. In some settings, blood can be purchased from a ‘private’ blood bank; however, since these frequently rely on paid donors, the chance of receiving unscreened blood – with its potential risk of transmission of HIV or hepatitis B – may be high.

In-depth assessments of availability and coverage of EOC have shown that in many cases, structures (i.e. health facility buildings and basic infrastructure) are in place, but these health facilities cannot offer EOC. This may be because of a shortage of drugs, equipment or human resources or of maldistribution of available resources. The combination of a lack of knowledge and skills is a key reason why many beneficial evidence-based practices are still not used by healthcare workers in many resource-poor settings.

Early newborn care

Complications of pre-term birth, infections and intrapartum-related asphyxia are the most frequent sources of neonatal deaths in resource poor settings (Fig. 29.12). Fourth and fifth are congenital abnormalities and tetanus, respectively. Together, these five causes account for 90% of all newborn deaths globally.

Infections, in particular sepsis, pneumonia and meningitis, can generally be prevented through good antenatal care, hygienic care during birth, care of the cord after birth and early exclusive breastfeeding. Recognition and early case-management of a baby with infection is needed both at hospital and community level. Postnatal care in the first week of life is crucial to implement this.

Tetanus is wholly preventable with vaccination of the mother and clean cord care. Complications of pre-term birth can be reduced if a mother is given antenatal corticosteroids when pre-term labour is recognized and Kangaroo Mother Care (carrying the baby skin-to-skin) is provided to low birth weight babies. Skilled birth attendance and emergency obstetric care – which includes resuscitation of the newborn – will reduce deaths from asphyxia.

Availability and quality of care

Delivering prompt and appropriate health care can be very challenging. In many settings, women and their families do not have access to the health care they need and availability of care may be limited. There are also factors that affect utilization (or uptake) of healthcare services, where these are available. Factors affecting utilization include socioeconomic and cultural factors, accessibility of healthcare facilities with regard to distance and cost and the quality of care. Many women will face possible delays in access to care, which include delay in deciding to seek care (Phase 1 delay), the speed/ease of identifying and reaching a healthcare facility (Phase 2 delay) and the timeliness and appropriateness of treatment received (Phase 3 delay).

The poor performance of health services in under-resourced countries is often compounded by broken equipment, poor logistical support and shortages of drugs and equipment. Countries need to ensure a balanced investment, not only in human resources, as well as infrastructure. Improved management ensuring no stock-outs of drugs, equipment, vaccines, etc. is crucial, as is an established and functional referral pathway from community to health facility and between health facilities.

Where services are not free, a lack of money to pay for services can determine when or if at all a woman seeks care, lack of transportation can delay seeking care (Fig. 29.13) and lack of properly trained staff will increase the risk of poor quality care that is not timely or appropriate or the risk of failure to recognize that a woman needs care.

While some progress has been made in reducing maternal and child deaths globally, a great deal still needs to be done in regions and countries of the world with the greatest burden. Increasingly, it is recognized that within countries there are wide disparities between rural and urban populations and between families in the lowest and highest wealth centiles. Recent efforts have seen a renewed focus on ensuring good quality evidence base, woman and baby friendly care is available for all.

There is need for continued advocacy globally to sustain international aid for resource poor countries together with improved governance and accountability.