Stone disease of the urinary tract

Pathophysiology of stone disease

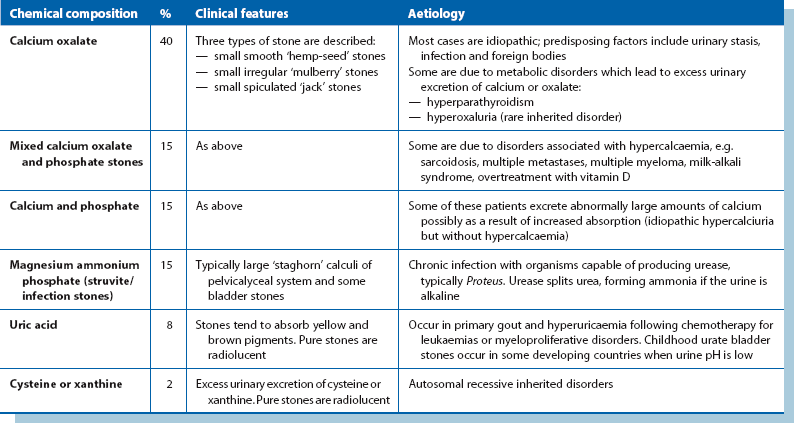

Stones are often formed from a mixture of chemical substances and minerals (e.g. calcium and oxalate) when their concentration exceeds their solubility in urine. Intermittent periods of super-saturation due to dehydration, following meals or medical conditions, can lead to the earliest phase of crystal formation. Lack of crystallisation inhibitors in the urine may also play a role in stone formation. Table 37.1 provides a simple chemical classification showing the relative frequency of stone types and their important clinical characteristics and aetiology. Calcium is present in approximately 80%, as oxalate or phosphate compounds or both. The aetiology of stone disease is multifactorial in most cases.

Clinical features of stone disease

The clinical presentation of stones depends on the size, morphology and site of the stone(s). Many cause no symptoms but represent a potentially serious problem. Other stones produce marked pathological effects which present with acute or chronic symptoms or are discovered incidentally on investigation of unrelated symptoms. The presentation of urinary tract stones is summarised in Box 37.2.

Obstruction of urinary flow

Passage of stones into the ureter

If small renal stones pass into the ureter, there are several possible outcomes:

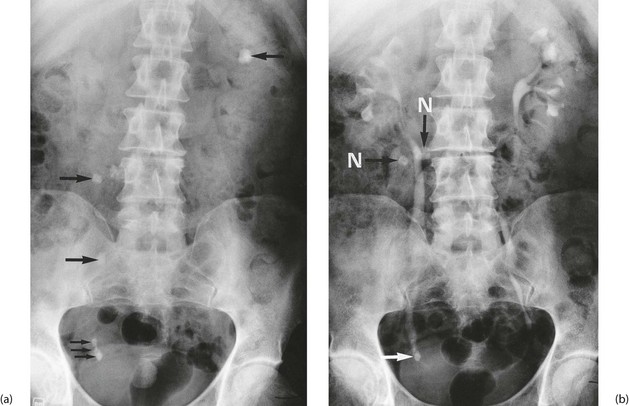

• Stones may pass to the bladder and exit via the urethra causing minor symptoms. The patient may intermittently pass ‘gravel’ or ‘sand’ (see Fig. 37.2) and experience dysuria and sometimes haematuria

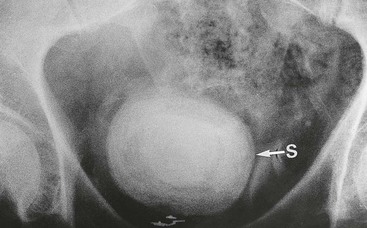

• Stones may pass into the bladder and act as a nidus for a larger bladder stone. Bladder stones occasionally cause bladder outlet obstruction and urinary retention

• A stone may impact in the ureter causing chronic partial obstruction and eventually hydroureter. This presents typically as loin pain but, surprisingly, may be asymptomatic

• A stone may impact in the ureter, causing sudden obstruction. The patient experiences extremely severe, unilateral colicky pain (ureteric colic) radiating from loin to the groin or tip of the penis. There is often loin tenderness due to renal distension. The pain is due to waves of ureteric peristalsis and at the peak of the pain, the patient writhes in agony

Predisposition to infection

Stones predispose to infection by causing urinary stasis, by preventing proper ‘flushing’ of the tract and by providing niches in which bacteria multiply. Pelvicalyceal or ureteric stones can cause acute pyelonephritis and occasionally a perinephric abscess. Bladder stones predispose to cystitis and ascending infections (see Fig. 37.3).

Investigation and management of suspected urinary tract stones

When investigating a patient with urinary tract stones, the objectives are:

Methods of investigation

• Urine dipstick testing, microscopy, culture and sensitivities

• Tests of renal function, i.e. plasma urea, electrolytes and creatinine levels

• A ‘KUB’ (kidney, ureter, bladder) plain abdominal X-ray. Around 90% of stones are radiopaque because they contain calcium. Urate stones are radiolucent

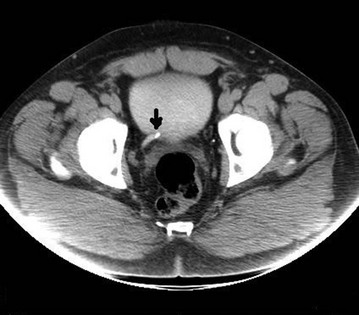

• CT imaging of the abdomen and pelvis. In developed countries, this has become the standard modality for diagnosing loin pain and renal tract stones (Fig. 37.4)

• Intravenous urography (IVU). This consists of a pre-injection KUB and further films at 5–20 minutes after injection of radiopaque contrast and after micturition. Figure 37.2 shows an IVU with the effects of stone obstruction

• Renal ultrasonography. This demonstrates hydronephrosis as well as the stones

• Special contrast techniques. These are occasionally required when other techniques do not give the required information, e.g. percutaneous (antegrade) pyelography or ascending (retrograde) ureterography

• Biochemical analysis of any recovered stones

• Tests for metabolic disorders (for recurrent stones), i.e. serum calcium, phosphate, oxalate, uric acid and alkaline phosphatase; 24-hour urinary excretion of calcium, uric acid and cysteine

Indications for stone removal (Box 37.3)

The finding of a urinary tract stone is not an automatic indication for its removal or destruction. The exception is in airline or military pilots in whom ureteric colic could prove disastrous. The usual indications for stone removal are summarised in Box 37.3. Small stones in the pelvicalyceal system often remain unchanged and asymptomatic for many years and can safely be monitored by annual radiography. Stones of 5 mm or less in diameter often pass right through the tract, although in doing so they may produce severe but short-lived symptoms of ureteric colic, haematuria or dysuria.

Methods of stone removal

Cystoscopic techniques

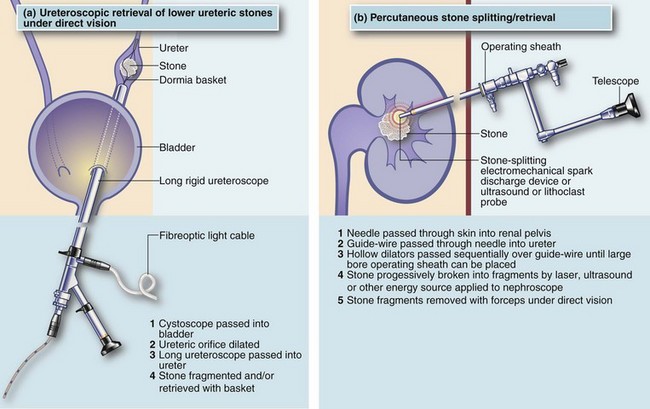

Cystoscopic methods (Fig. 37.5) are suitable for most bladder stones and for impacted stones in the lower third of the ureter. Bladder stones can be broken into small fragments (litholapaxy) using a stone punch or lithotrite, a cystoscope incorporating stone-crushing jaws. The fragments are then washed out by irrigation. Stones can also be fragmented by directly applied pulsed ultrasound, laser or other energy sources via a cystoscope.

Fig. 37.5 Instruments for urinary stone removal

(a) Straight stone punch (lithotrite). A telescope fits through the centre of the lithotrite, allowing a direct view as the stones are crushed between the jaws. Note: the jaws are closed before passing the instrument into the bladder via the urethra. (b) Dormia basket and grasping forceps. The Dormia basket (centre and left) is advanced beyond the stone in the ureter and then opened by advancing the centre wire from the proximal end. When open (left), the whole instrument is gradually withdrawn until the stone lodges within the wire basket. The centre wire is then withdrawn further until the stone is firmly held within the basket and the whole instrument withdrawn complete with stone. The trident grasper (right) operates in a similar way, grasping the stone as the wire is retracted

A rigid ureteroscope can be used to examine the entire length of the ureter and assist with stone removal (see Fig. 37.6a), as well as to apply energy via laser fibre, ultrasonic, electrohydraulic, or lithoclast probes directly onto the surface of a stone to destroy it. It can also help capture elusive stones via a Dormia basket (declining in popularity). Flexible ureteroscopes allow access to the renal pelvis and calyces so stone fragmentation can be achieved using holmium laser probes.

A ureteric stent may be placed after repeated instrumentation of the ureter to assist drainage. If an impacted stone is causing complete ureteric obstruction and leading to marked proximal dilatation, or if there is infection, a percutaneous nephrostomy tube should be inserted above the stone without delay (see Fig. 37.7, p. 470) to preserve renal function.

Percutaneous techniques of stone removal

Direct percutaneous access to the renal pelvis can be obtained using radiological or ultrasound guidance. This allows a track to be created from the skin of the loin into the pelvicalyceal system (nephrostomy) under local anaesthesia, through which progressively larger instruments can be passed. Small stones can be retrieved using a basket or a steerable grasping tool. Larger stones can be broken into fragments with laser, ultrasonic, electrohydraulic or other probes, after which the fragments can be lifted out with special instruments (see Fig. 37.6b). The nephrostomy track closes spontaneously after a short period.

Management of acute ureteric colic

Many patients settle with a single analgesic dose but two or three doses may be required. In most cases, the stone gradually passes down the ureter and into the bladder. Each stage of movement may be accompanied by an attack of colic. If a stone is retrieved, it should be chemically analysed. If there is complete obstruction of the ureter, or infection above an obstructing stone, urgent intervention is usually required to prevent renal damage. Immediate treatment may involve placing a percutaneous nephrostomy tube to drain the renal pelvis (see Fig. 37.7), placing a stent beside the stone to allow drainage, or removing the stone endoscopically. After nephrostomy or stent placement, the stone sometimes passes spontaneously but more often further treatment is required. In cases with persistent pain not needing immediate intervention, plain abdominal X-rays usually record changes in the stone’s position. Very large stones may have to be surgically removed. If a stone appears to be small enough to pass spontaneously, yet fails to progress, the patient can safely be allowed home provided criteria for urgent intervention are not fulfilled. The patient can be reviewed after a week or two with a plain abdominal X-ray and a decision taken then about any need for intervention.

Fig. 37.7 Percutaneously placed nephrostomy drainage tube

A ureteric stone caused complete ureteric obstruction and the patient suffered continuing pain and developed a fever. Urgent drainage was required to prevent renal damage from a combination of obstruction and infection

Investigation of ureteric colic

Ureteric colic almost always causes microscopic haematuria, so the first investigation is ‘dipstick’ testing of urine for blood; if positive it should be confirmed on microscopic examination. A positive result reinforces the diagnosis. A CT scan or an IVU should then be performed urgently to confirm or refute the diagnosis (see Fig. 37.4, p. 467).

Characteristic radiological features of acute ureteric obstruction on IVU are:

• Delay of all phases of contrast passage through the kidney and collecting system on the affected side; the more severe the obstruction, the longer the delay. If there appears to be no excretion, further films are taken every few hours for up to 24 hours; usually contrast will eventually pass into the system, demonstrating the site of obstruction

• Dilatation of the collecting system above the point of obstruction