CHAPTER 3

Stomach

INTRODUCTION

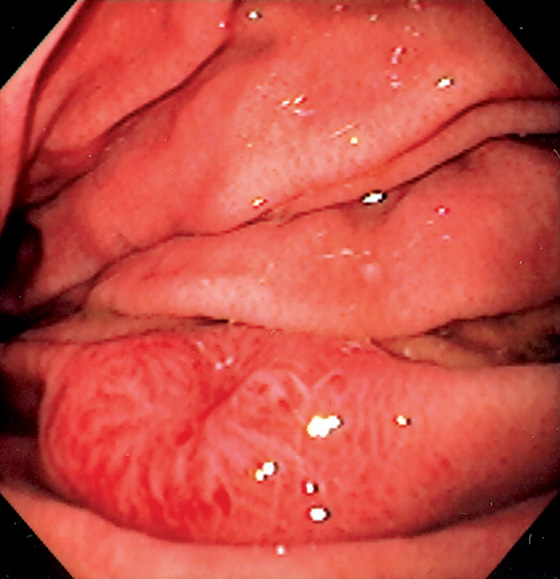

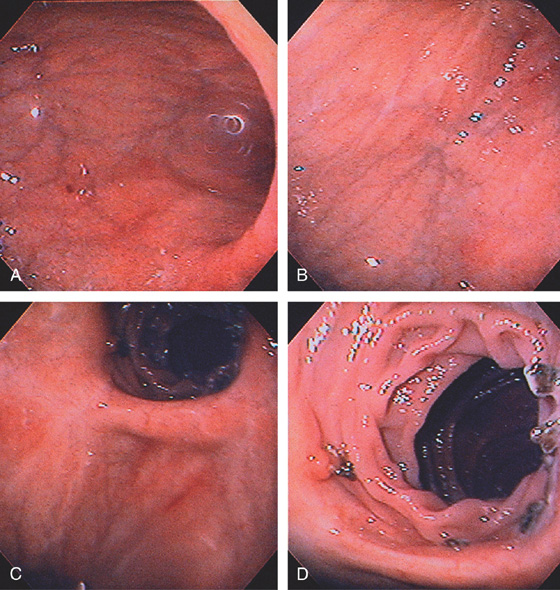

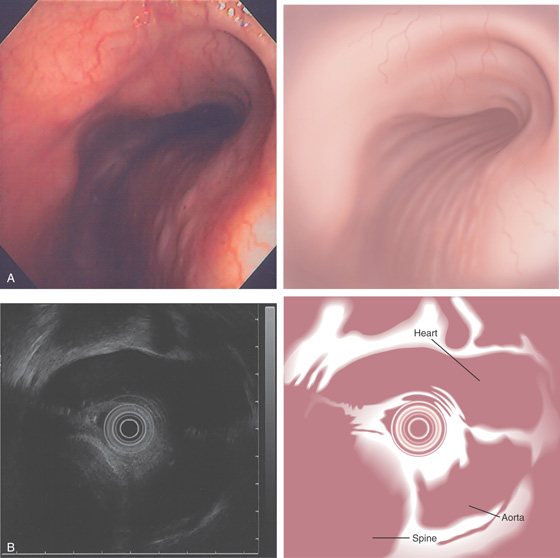

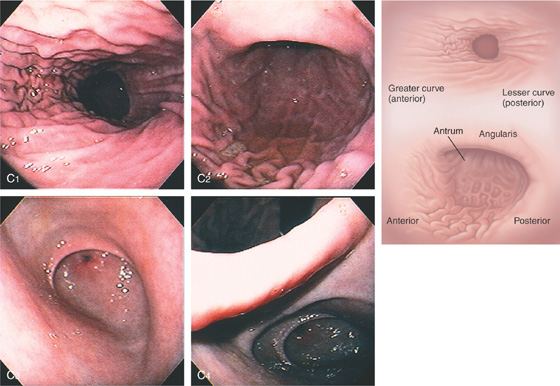

The stomach functions to store food and begin the process of digestion. It can be divided physiologically, anatomically, and endoscopically. Upon entering the stomach, one looks directly toward the greater curvature and encounters the gastric rugae. On close inspection, the mucosa has a subtle mosaic pattern, representing the areae gastricae. Any process causing mucosal edema will accentuate this pattern. Gastric folds should flatten with full insufflation. The incisura angularis (gastric notch), located on the distal lesser curvature, is an important landmark that helps to differentiate the gastric body from the antrum and is a common location for benign gastric ulceration. Not unexpectedly, given the histologic differences, the antral mucosa appears endoscopically different from the gastric body.

Inflammatory disorders are the most common gastric disorders encountered by endoscopists. As with any endoscopic abnormality, gastric ulcers should be thoroughly characterized, noting location, size, and appearance, because these characteristics yield important information about the likelihood of neoplasm. Similarly, improved resolution with newer endoscope systems has increased the sensitivity for the endoscopic detection of histologic gastritis. Helicobacter pylori gastritis may be suspected at the time of endoscopy, although definitive diagnosis requires confirmation, given that “endoscopic abnormalities” may represent normal findings, and conversely, a normal endoscopic appearance may not represent normal histology.

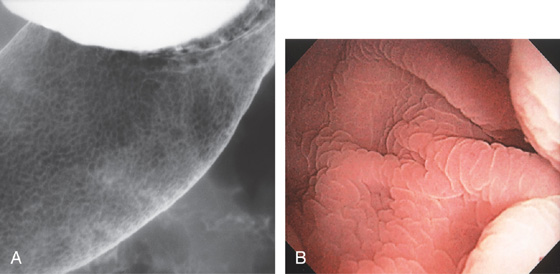

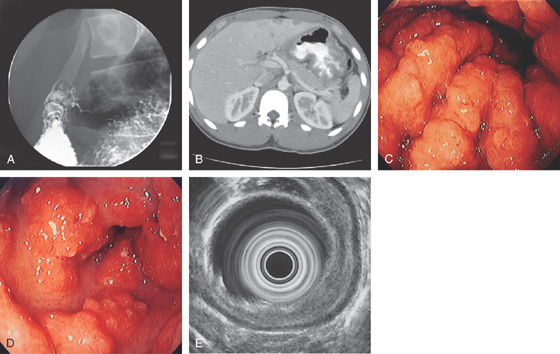

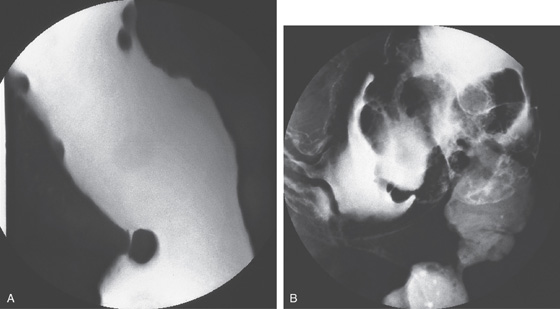

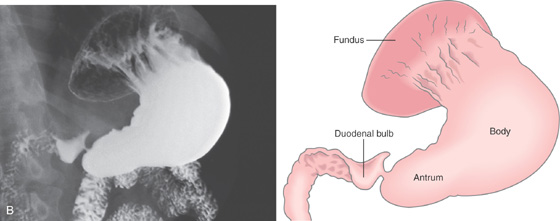

A, The gastric fundus is well filled with barium, providing an air contrast view of the body, antrum, and duodenal bulb. Normal-appearing gastric rugae are seen in the proximal body. The antral and duodenal mucosae are smooth. Barium is entering the second portion of the duodenum.

B, Barium is filling the gastric body and antrum, showing normal contour. An air contrast view of the gastric fundus is shown. The distal duodenum and proximal jejunum are inferior to the gastric body.

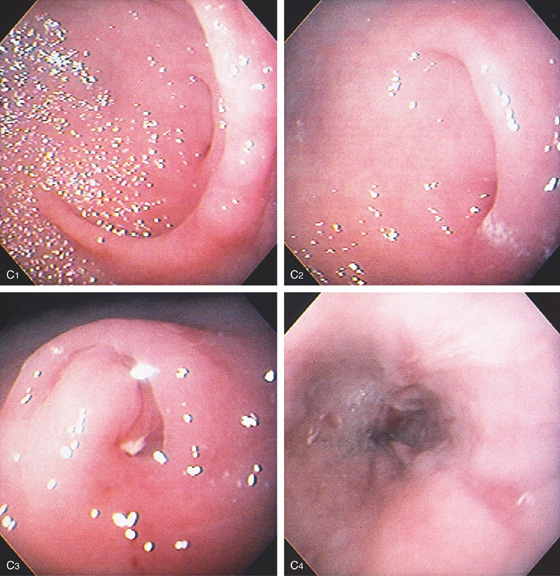

C, As the endoscopic tube enters the stomach, the greater curvature is on the left and the lesser curvature on the right, with the angularis (i.e., incisura angularis) in the distance. Gastric rugae are more prominent on the greater than the lesser curvature (C1). Normal-appearing rugae are seen in the distal body, extending to the level of the angularis (C2). The antral mucosa is smooth, and the pylorus is in the distance (C3). The endoscope tip is elevated, and the scope is rotated slightly to the left, identifying the pylorus and angularis, with the endoscope seen above (C4).

Figure 3.1 NORMAL ANATOMY

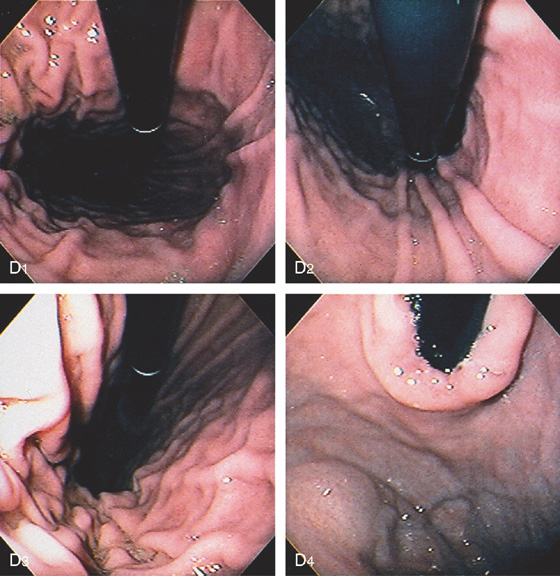

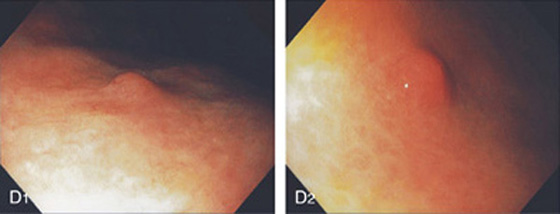

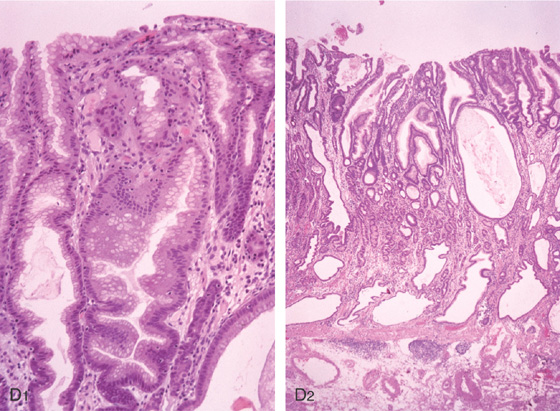

D, The endoscope is withdrawn to the level of the angularis. The lesser curvature forms the right wall and the greater curvature the left wall. The gastric rugae are more prominent on the left wall (D1). With further withdrawal of the endoscope, small rugae are seen on the lesser curvature (D2). More prominent rugae are on the opposite wall (greater curvature) with the endoscope rotated to the left (D3). With still further withdrawal of the endoscope, the gastric fundus and cardia are shown. The fundus has no rugae, and blood vessels are present. A small rim of gastric mucosa (gastric cardia) can be seen encircling the endoscope (D4).

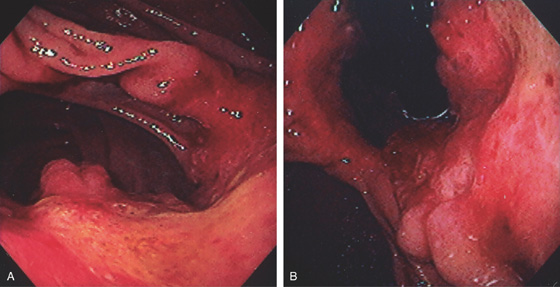

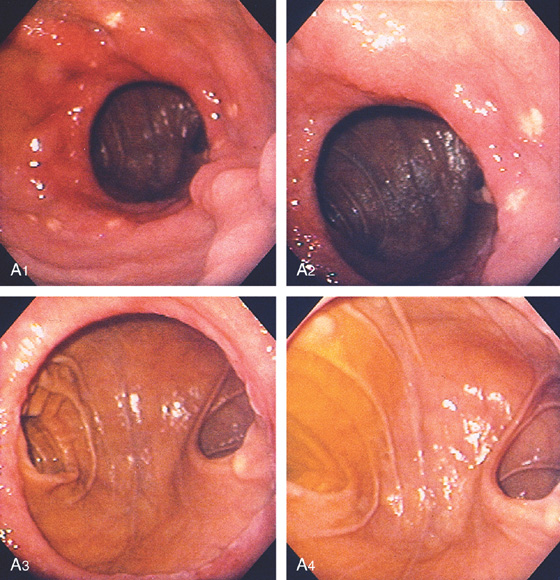

Figure 3.2 ANTERIOR–POSTERIOR RELATIONSHIP

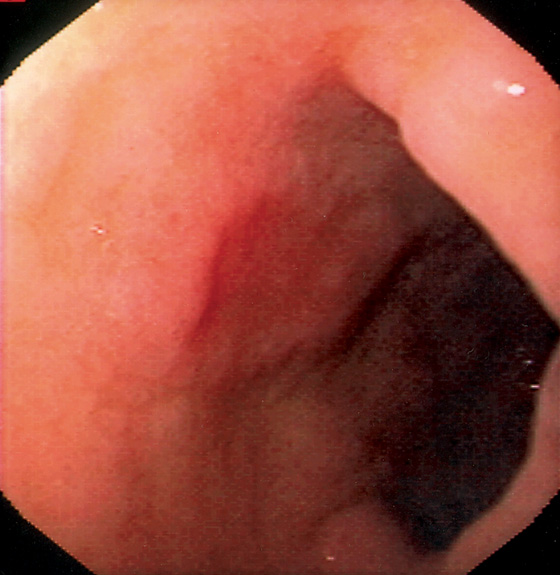

With the patient supine, indentation of the anterior wall documents the anterior–posterior relationship of the angularis.

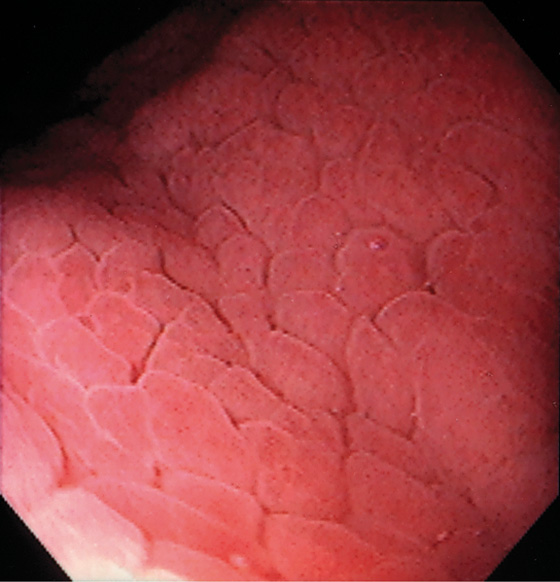

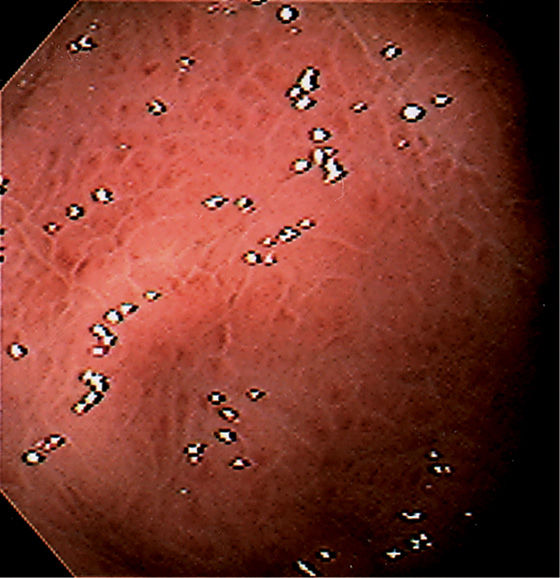

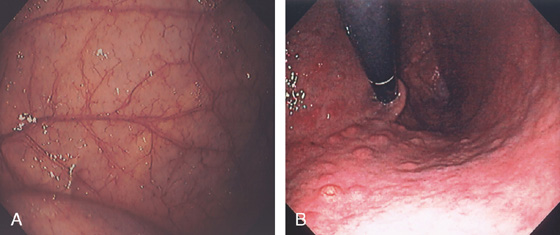

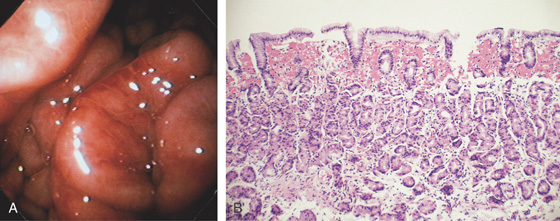

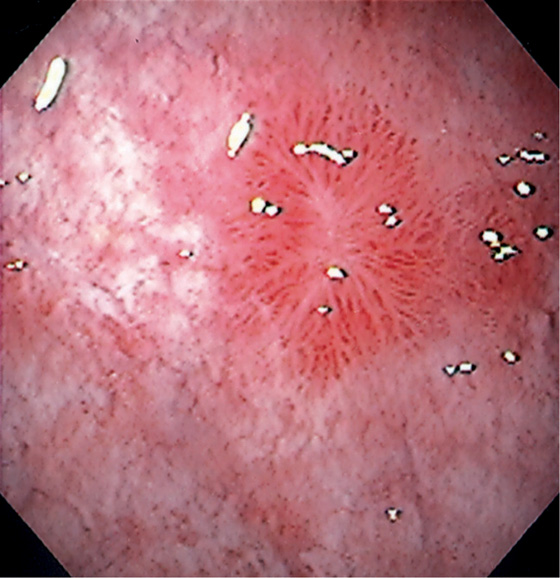

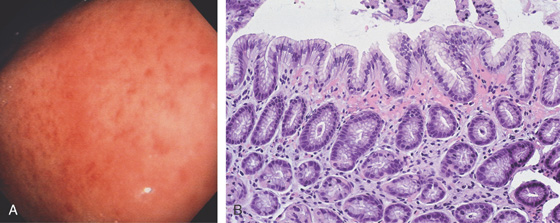

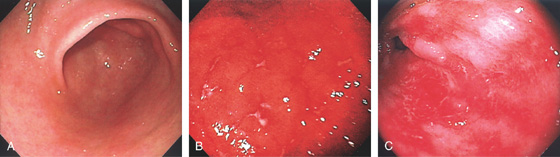

Figure 3.3 AREAE GASTRICAE

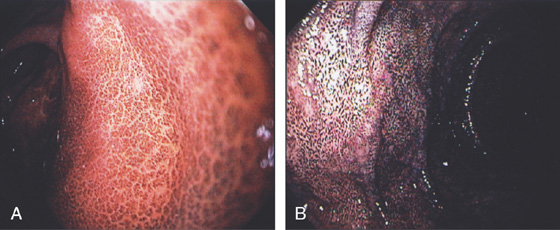

A, This pattern may be seen in healthy individuals or can be associated with gastritis. Endoscopically, the pattern may not be as well appreciated as with a barium study. B, The normal areae gastricae as seen underwater. Clarity is enhanced when structures are viewed underwater.

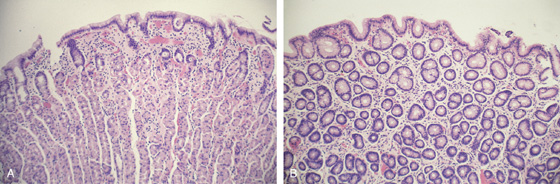

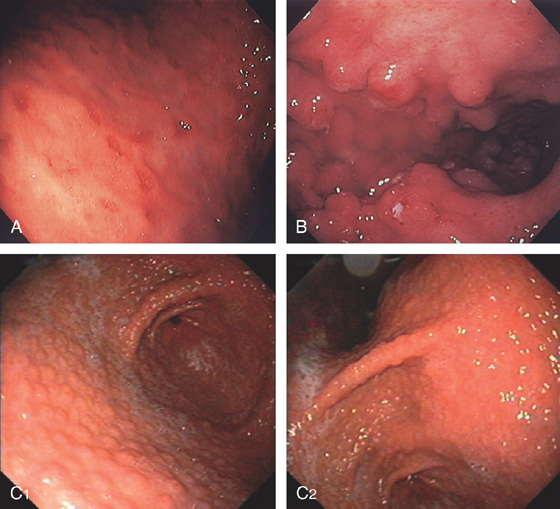

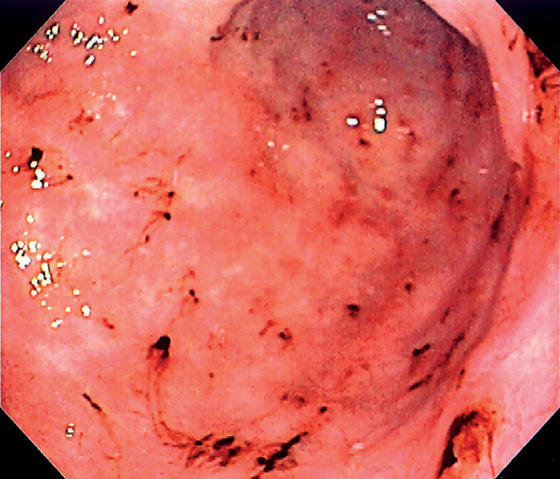

Figure 3.4 GASTRIC HISTOLOGY

A, The normal histology of the gastric body is demonstrated. The foveolar surface epithelium is shown. The deeper structures represent the fundic glands. The vertical orientation of the glands is evident. B, The normal antral mucosa is composed of deep pits lined by foveolar epithelium. Mucin-producing glands are present.

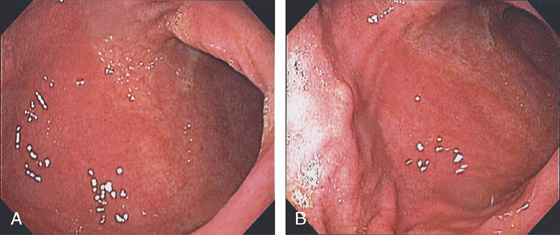

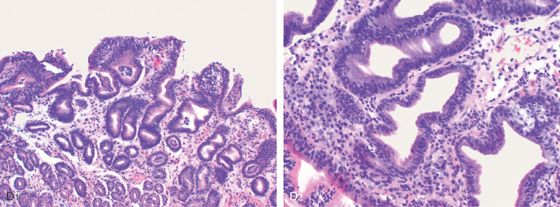

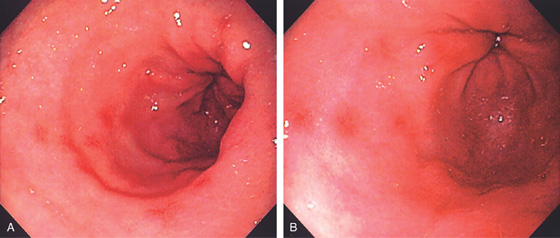

Figure 3.5 GASTRIC BODY–ANTRUM DEMARCATION

A, B, The gastric mucosa often changes in appearance near the angularis, in association with the histopathologic change. This change may be more striking in patients with associated gastritis.

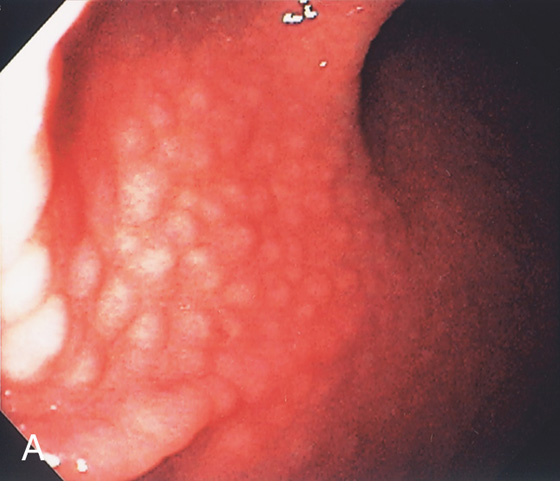

Figure 3.6 HELICOBACTER PYLORI GASTRITIS

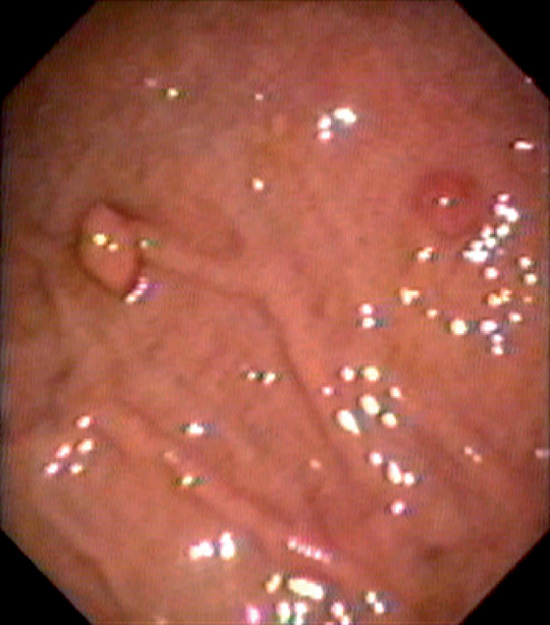

Mild superficial gastritis results in erythema and prominence of the areae gastricae (as seen underwater).

Figure 3.7 FOCAL HELICOBACTER PYLORI GASTRITIS

Patchy areas of inflammation in the proximal gastric body are well demarcated by the surrounding atrophic mucosa.

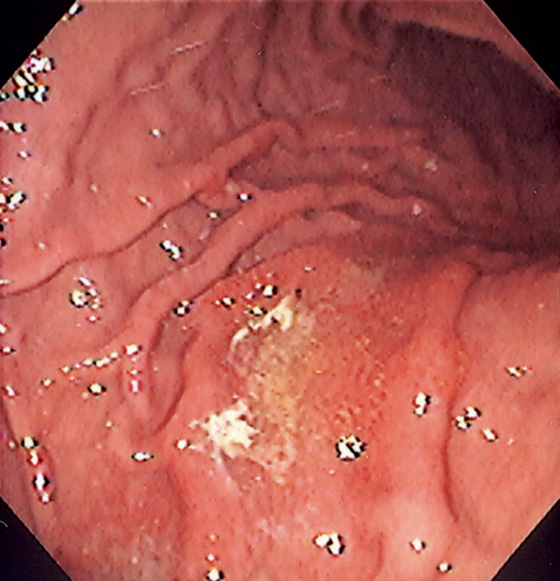

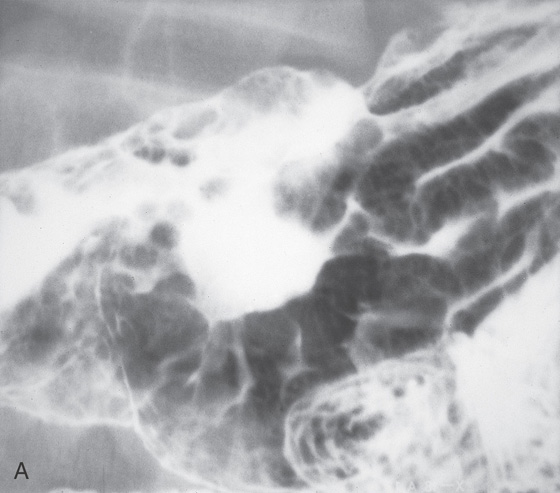

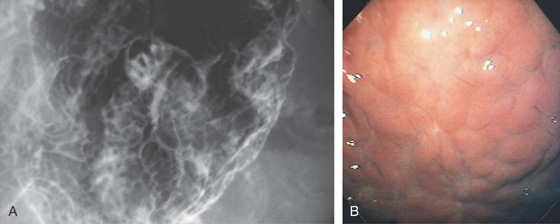

Figure 3.8 HELICOBACTER PYLORI GASTRITIS

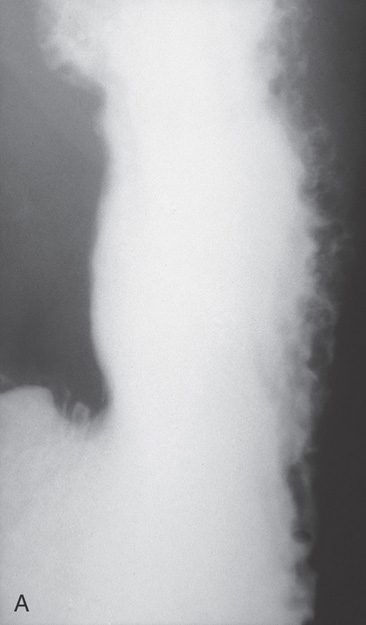

A, Multiple nodular filling defects and prominence of the areae gastricae in the gastric body. This pattern may represent inflammation or an infiltrating neoplasm. B, Diffuse nodularity, with overlying normal mucosa.

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Helicobacter pylori Gastritis (Figure 3.8)

Lymphocytic gastritis

Sarcoidosis

Lymphoma

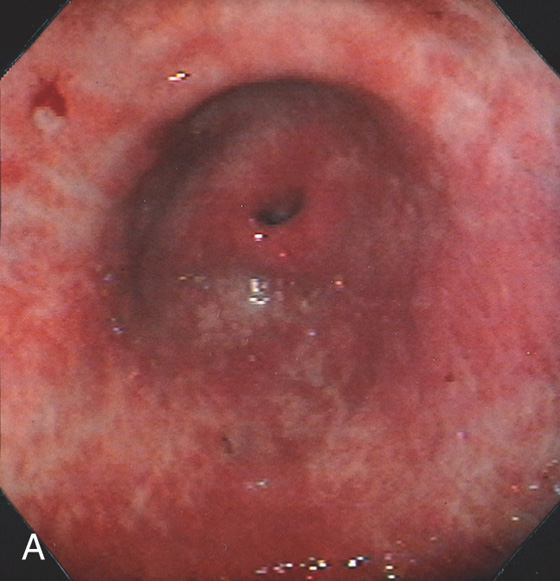

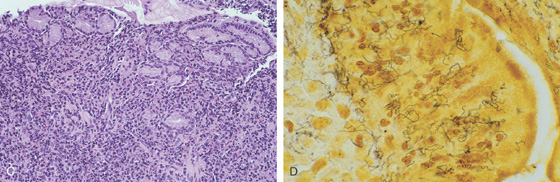

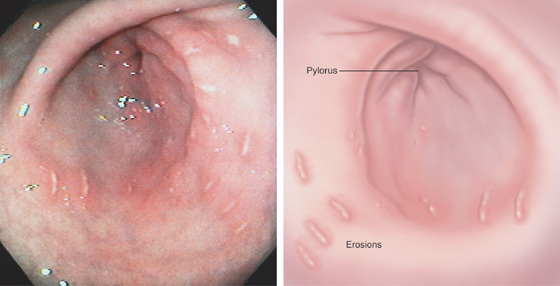

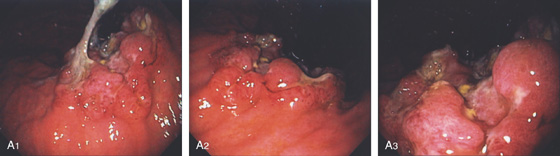

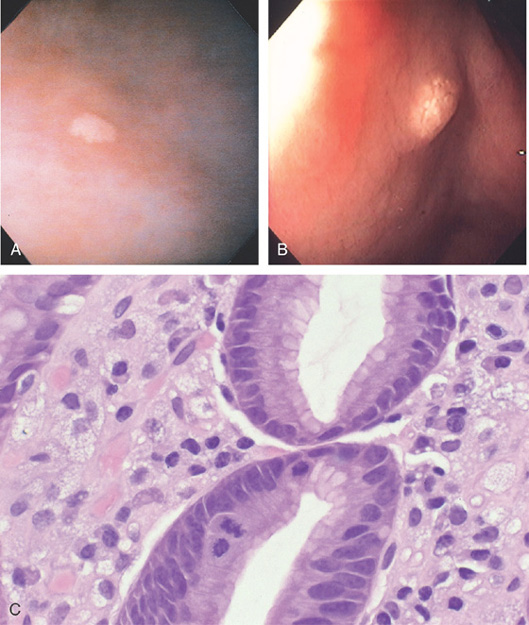

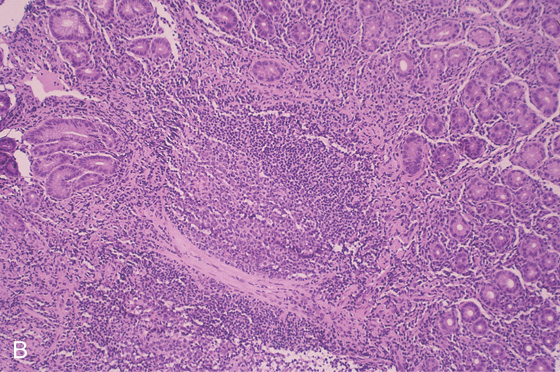

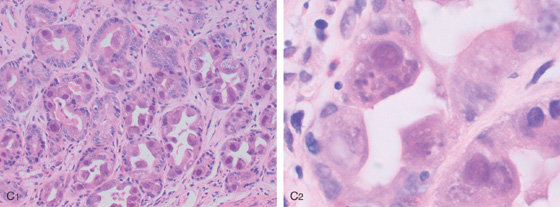

Figure 3.9 HELICOBACTER PYLORI GASTRITIS

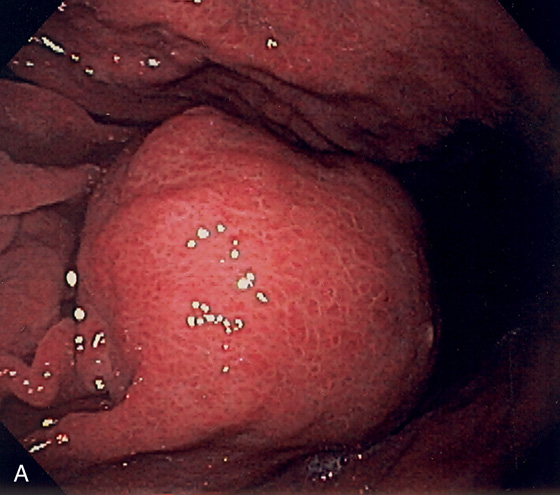

A, There is marked nodularity of the anterior wall of the gastric body when viewed from this angle. This has been termed a “chicken skin” appearance.

B, Follicular lymphoid hyperplasia associated with prominent chronic gastritis. An enlarged lymphoid follicle with germinal center is present.

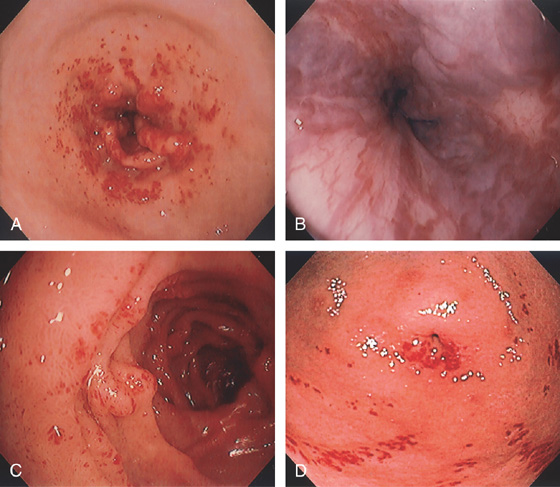

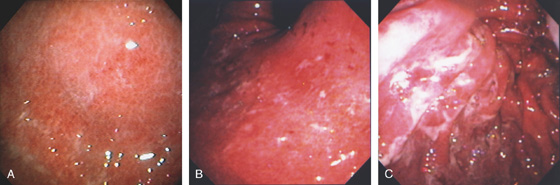

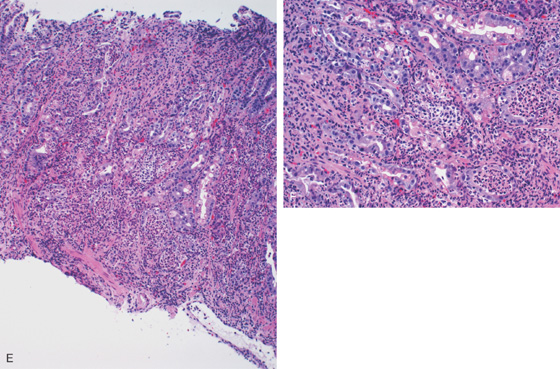

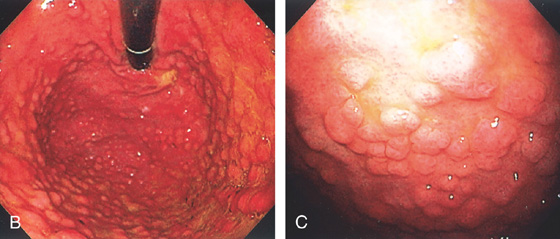

Figure 3.10 HELICOBACTER PYLORI GASTRITIS

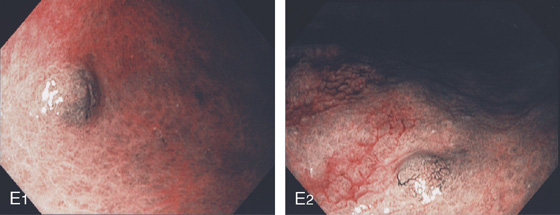

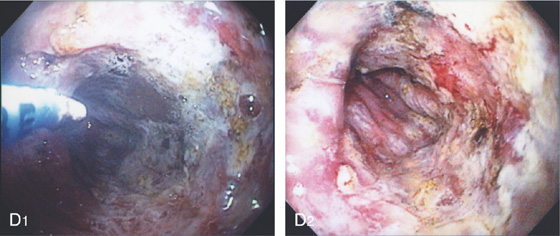

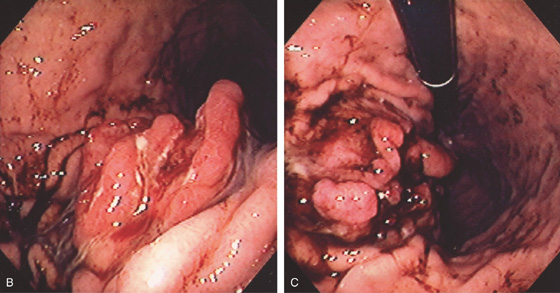

A, Severe gastritis in the gastric body, with edema, erythema, scattered subepithelial hemorrhage, and overlying exudate. B, C, Severe gastritis manifested by erythema and exudate.

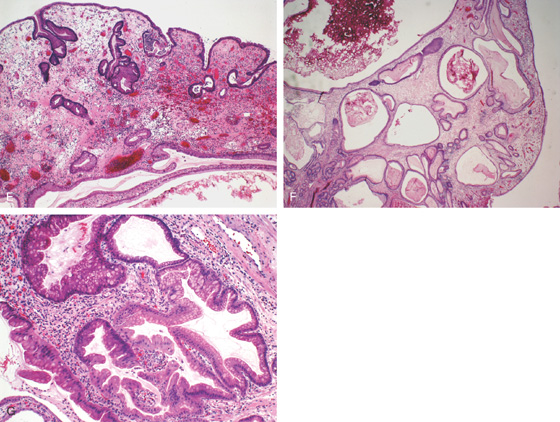

Figure 3.10 HELICOBACTER PYLORI GASTRITIS

D, Gastric body mucosa with severe acute and chronic inflammation and crypt abscess formation.

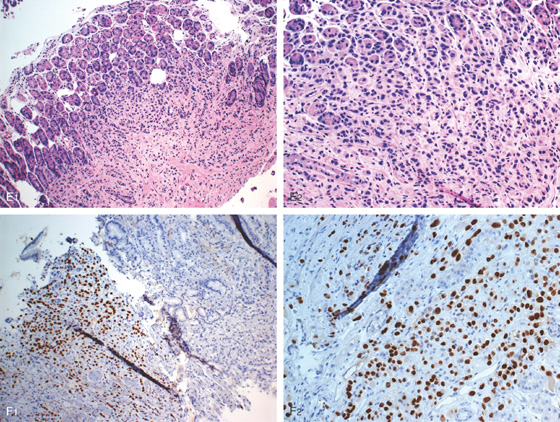

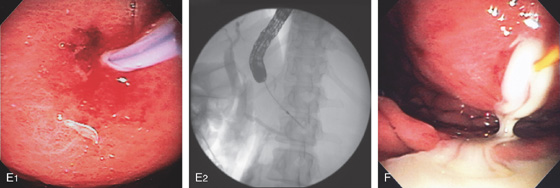

E-F, Gastric body mucosa with severe acute and chronic inflammation and crypt abscess formation.

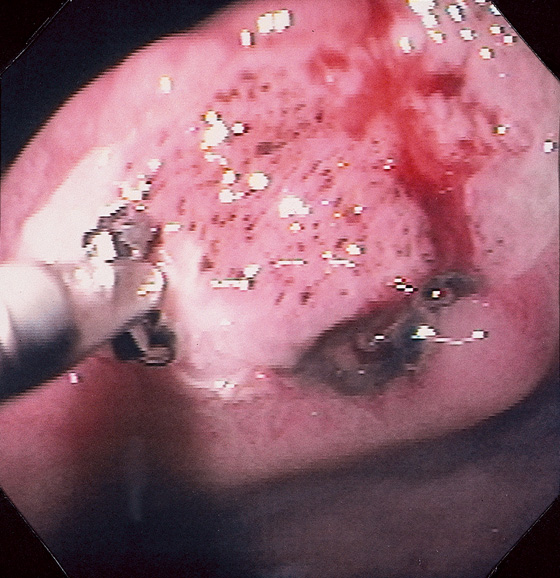

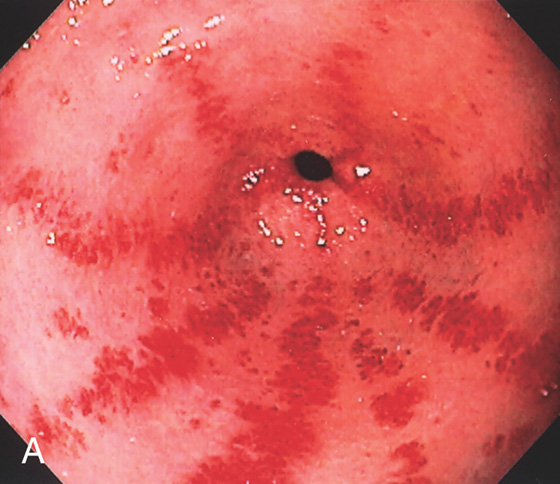

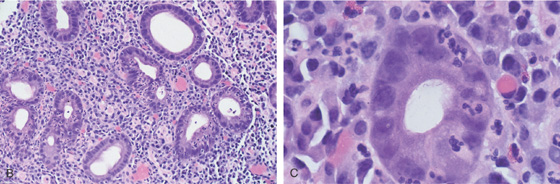

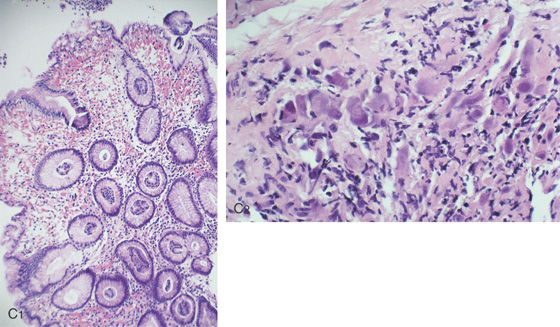

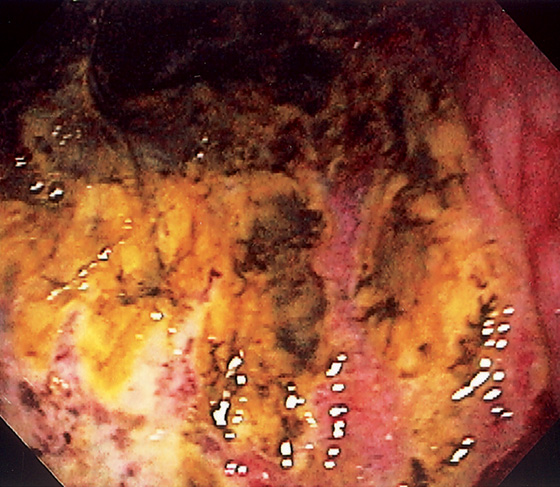

Figure 3.11 HELICOBACTER PYLORI ANTRAL GASTRITIS

A, A mottled appearance of the gastric antrum. The area of bleeding represents extreme friability.

B, Prominent chronic active gastritis. The pyloric glands are infiltrated by neutrophils, and increased numbers of chronic inflammatory cells are in the lamina propria. C, Close-up view of a gastric gland reveals infiltration with neutrophils. Organisms compatible with Helicobacter pylori are seen on the luminal surface of the epithelial cells.

Figure 3.11 HELICOBACTER PYLORI ANTRAL GASTRITIS

Special stains with Giemsa (D) and silver stain (E) better highlight the organism.

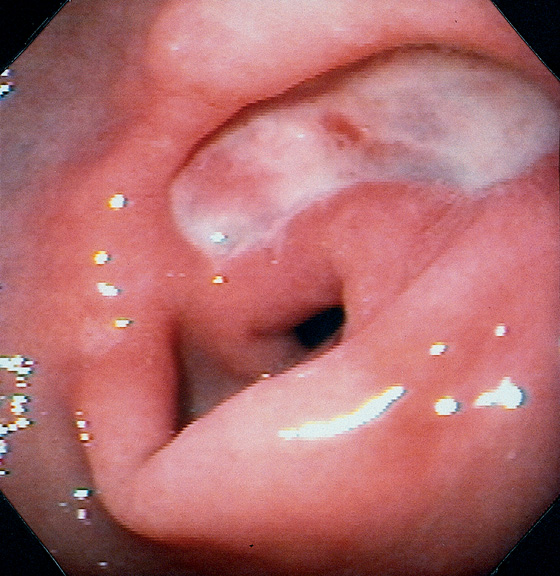

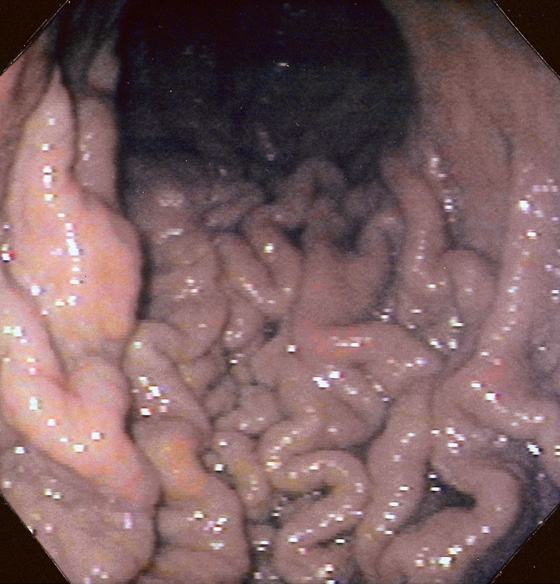

Figure 3.12 HELICOBACTER PYLORI GASTRITIS

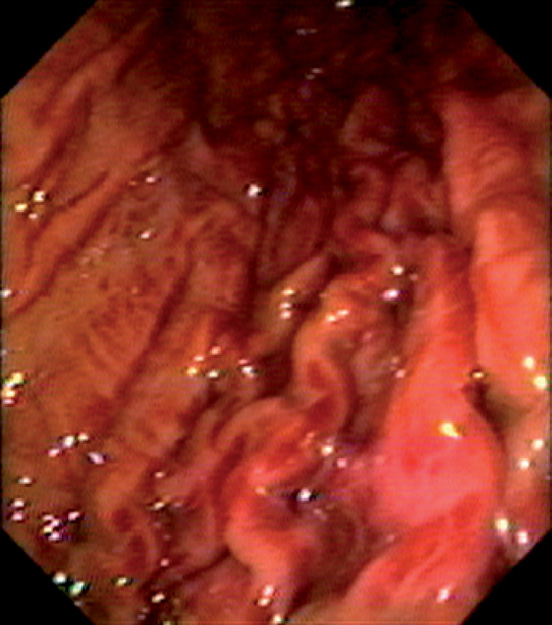

Marked prominence of the gastric rugae.

Helicobacter pylori Gastritis (Figure 3.12)

Ménétrier’s disease

Infiltrating neoplasms

Lymphoma

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome

Mastocytosis

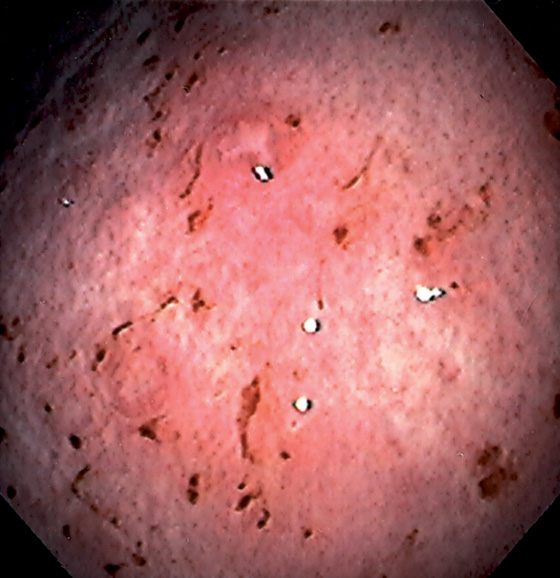

Figure 3.13 HELICOBACTER PYLORI GASTRITIS

The areae gastricae are prominent and there is associated subepithelial hemorrhage.

Figure 3.14 HELICOBACTER PYLORI GASTRITIS WITH SCARRING

End-stage H. pylori gastritis with atrophy and evidence of prior scarring, with “ghosts” of prior mucosal injury seen as linear areas of scarring with surrounding subepithelial hemorrhage and edema.

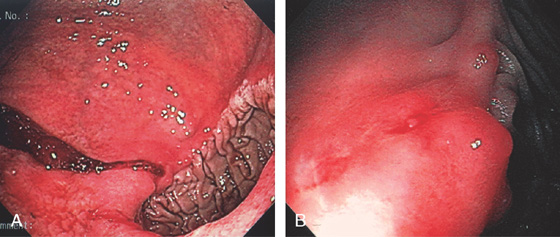

Figure 3.15 LYMPHOCYTIC GASTRITIS

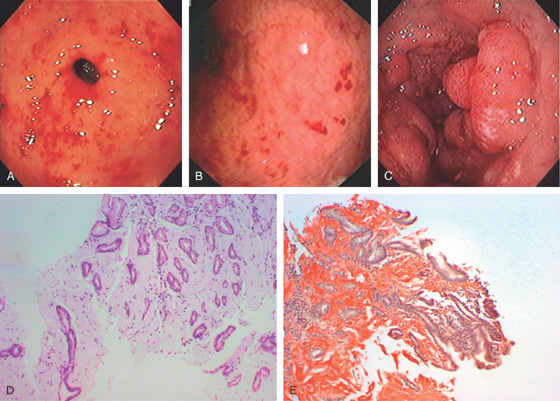

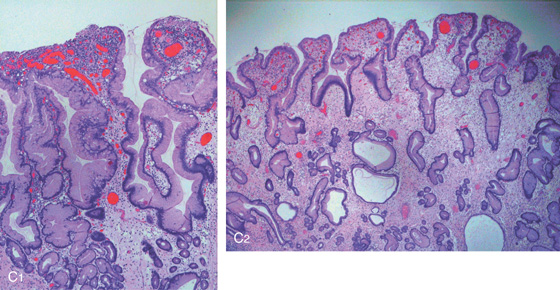

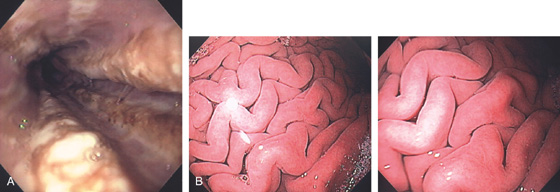

A, Multiple erosions of the gastric body. B, Multiple small polypoid lesions principally involving the gastric body. C, Diffuse nodularity of the distal (C1) and proximal (C2) stomach.

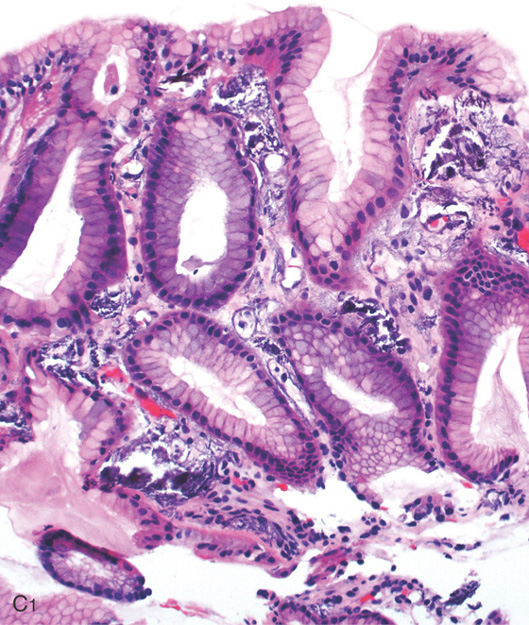

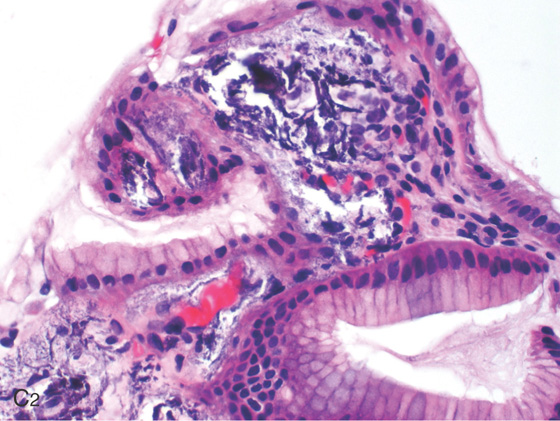

D1, Preserved architecture with an appearance of chronic gastritis. D2, Close-up shows a diffuse infiltration of lymphocytes in the mucosa.

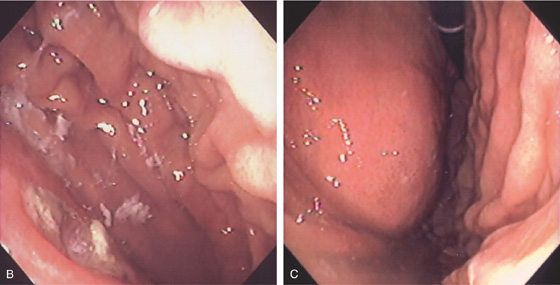

Figure 3.16 CHEMICAL GASTRITIS

Focal area of edema with exudate in the gastric body. Biopsies showed mild inflammation with foveolar hyperplasia. Iron was also present in the specimen. These findings suggest gastropathy induced by pills, in this case, iron.

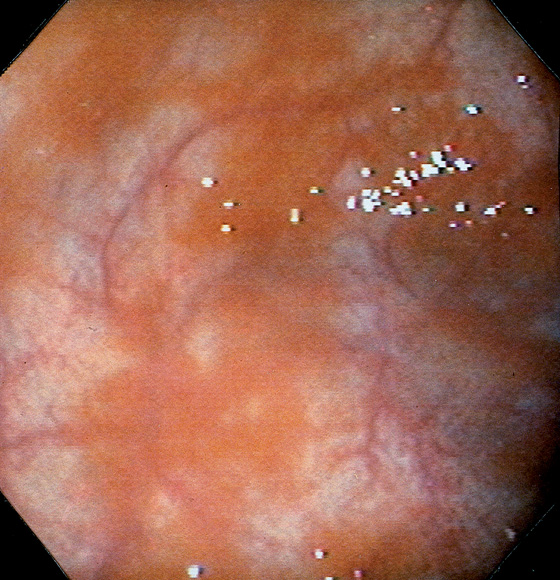

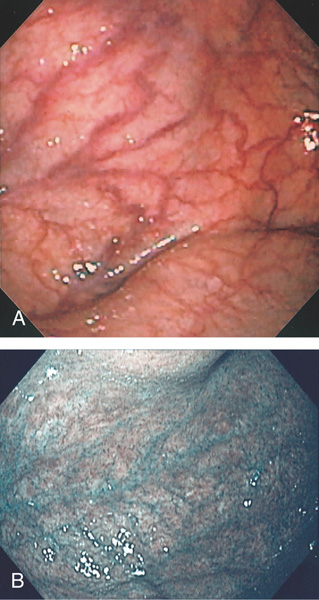

Figure 3.17 GASTRIC ATROPHY

A, The end result of long-standing Helicobacter pylori gastritis is atrophy. The gastric rugae are completely absent, with blood vessels easily seen throughout the gastric body and antrum. B, Narrow band imaging highlights the underlying vasculature.

C, Gastric atrophy and chronic gastritis.

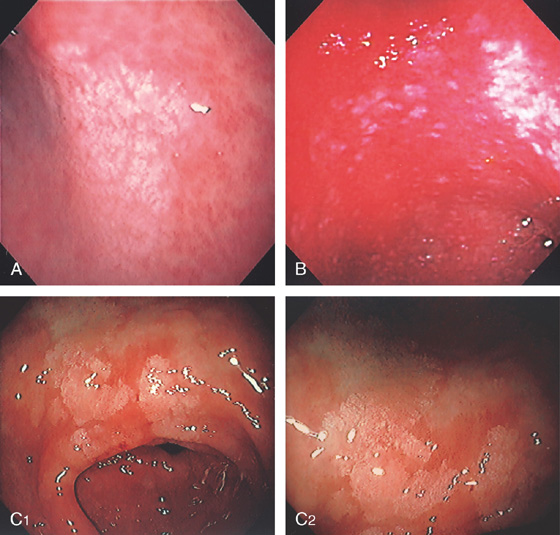

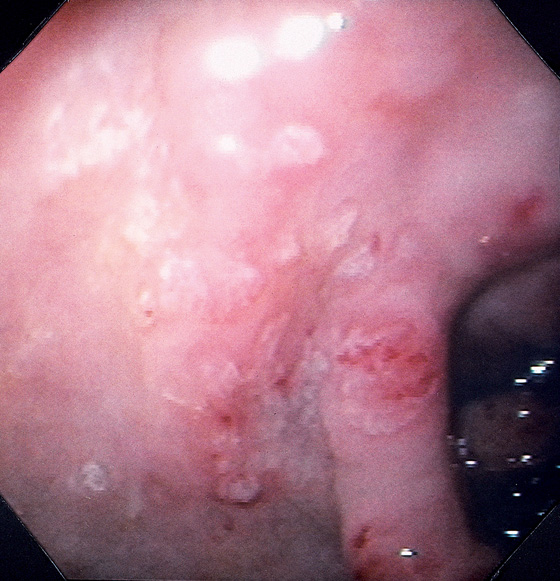

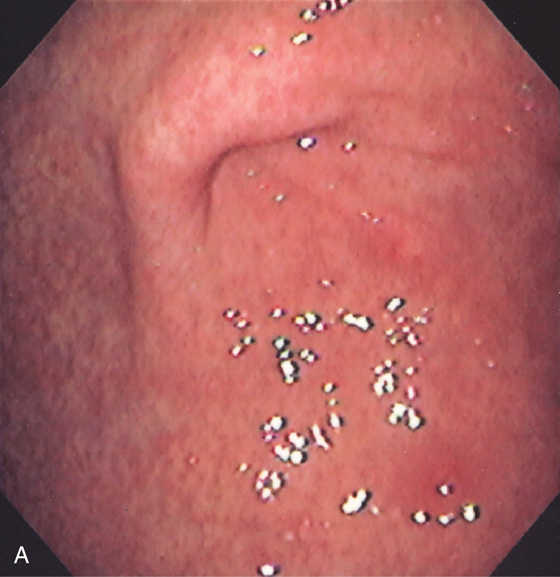

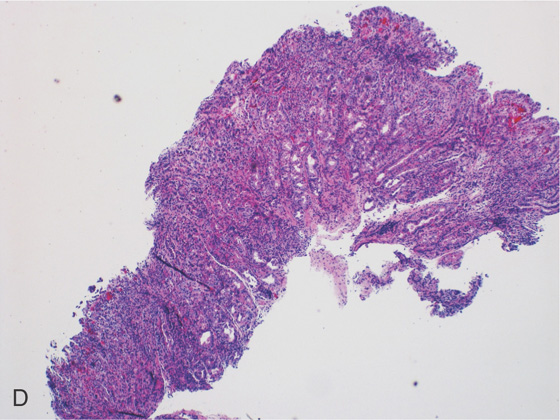

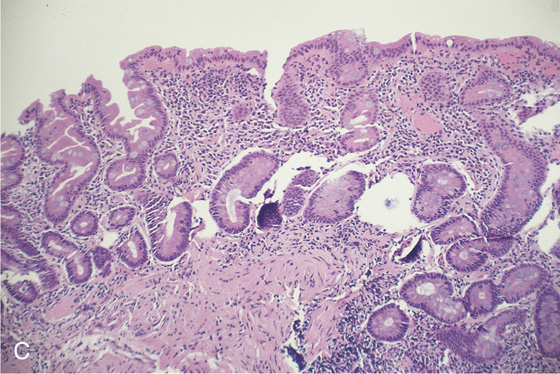

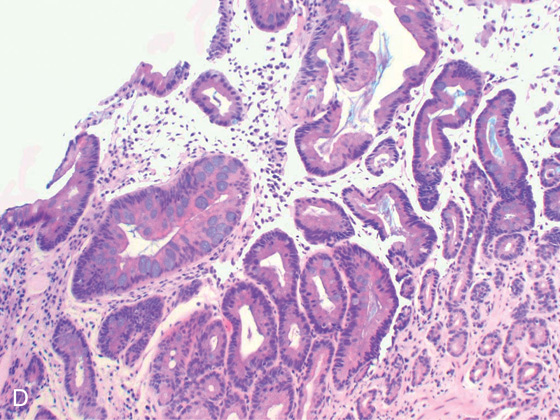

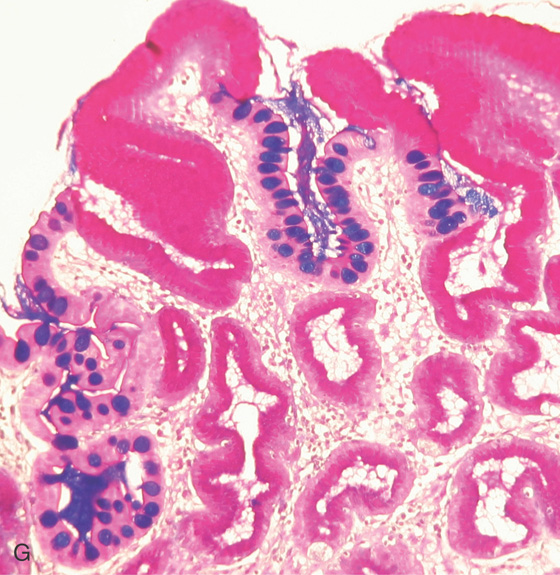

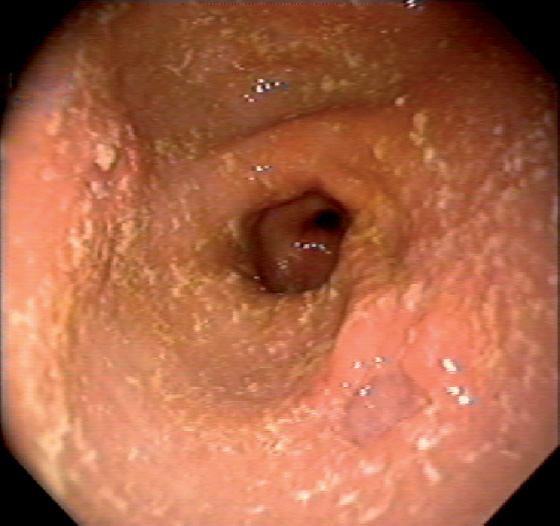

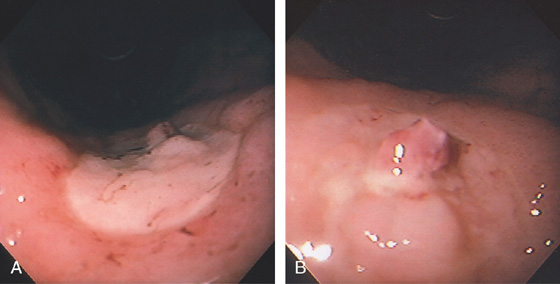

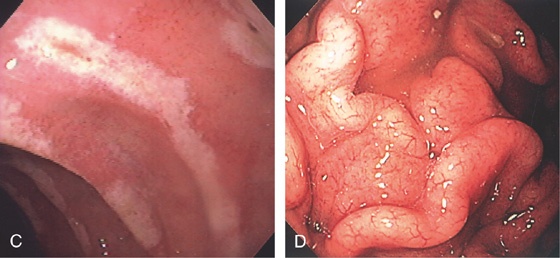

Figure 3.18 INTESTINAL METAPLASIA

A, Focal white plaquelike lesion of the antrum. B, Multiple white plaquelike lesions of the antrum. C1, C2, Multiple white plaquelike lesions with a verrucous appearance in the gastric antrum. Note that the surrounding gastric mucosa is relatively atrophic.

D, Numerous goblet cells are present, confirming the diagnosis.

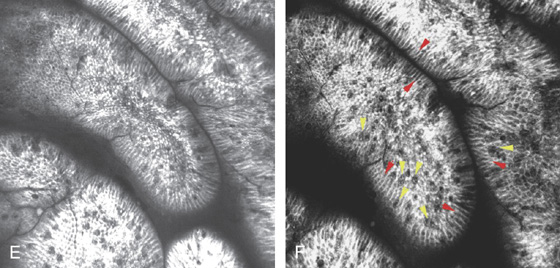

Figure 3.18 INTESTINAL METAPLASIA INTESTINAL METAPLASIA PATHOLOGY

E, Intestinal metaplasia as seen by optical coherence tomography. F, The goblet cells stain and brush border are visible (red arrows indicate brush border; yellow arrows indicate goblet cells).

G, Periodic acid-Schiff stain highlights the goblet cells. (F courtesy Cristian Gheorge, MD.)

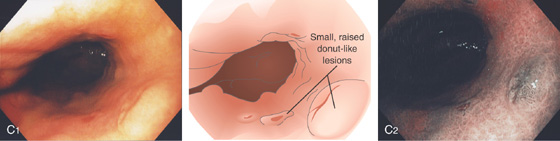

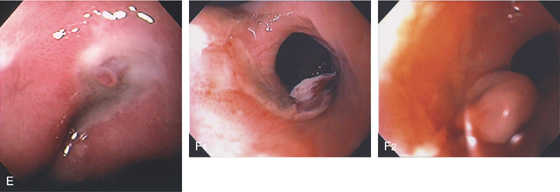

Figure 3.19 PERNICIOUS ANEMIA

A, Marked gastric atrophy with absent rugal folds and prominent vascular pattern. B, Multiple small polyps in the proximal body and fundus, which on biopsy were carcinoid tumors.

C1, Small, raised, donutlike lesions in the gastric body. C2, Appearance on narrow band imaging.

D1, D2, Small polyp on a background of gastric atrophy.

E1, E2, Appearance on narrow band imaging. These lesions were small carcinoid tumors.

Figure 3.19 PERNICIOUS ANEMIA

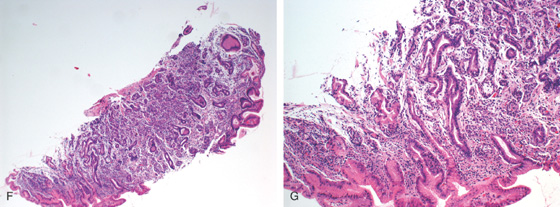

F, G, The mucosa is atrophic with decreased or absent parietal and chief cells, as well as presence of intestinal metaplasia.

H, At low-power view, a microcarcinoid tumor is shown. I, Enterochromaffin cells are seen in the mucosa.

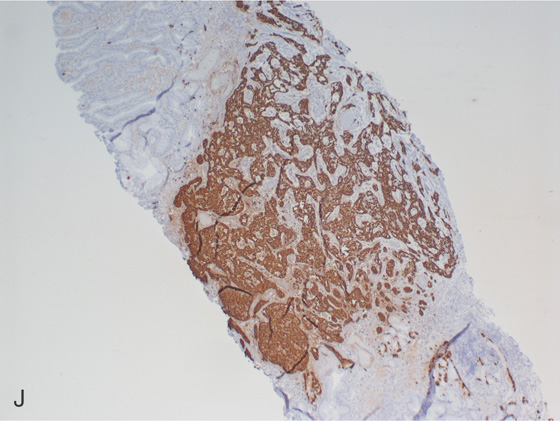

J, Chromogranin staining highlights the neuroendocrine tumor.

K, Chromogranin staining highlights the neuroendocrine tumor. L, Enterochromaffin cell hyperplasia/dysplasia at the base of the gland (blue arrow).

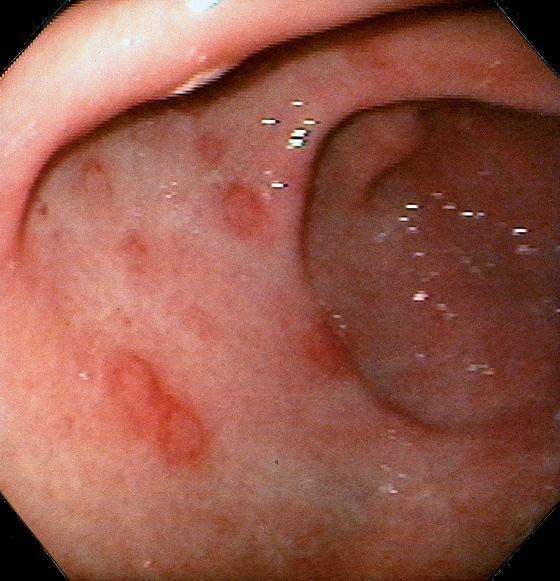

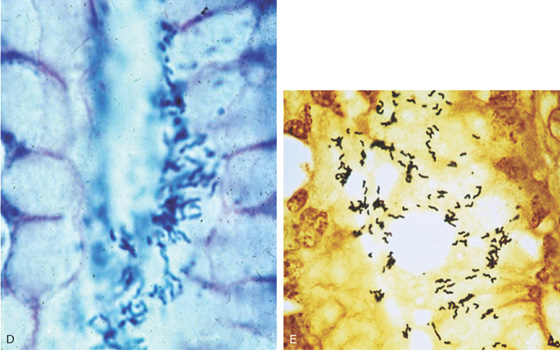

Figure 3.20 SYPHILIS

A, Large gastric ulceration, with prominent irregular rugae radiating to the lesion.

B, Irregularly shaped ulceration on the angularis, with nodularity of the ulcer rim.

Figure 3.20 SYPHILIS

C, Severe chronic inflammation composed primarily of plasma cells. A prominent plasmacytic infiltrate in a patient with positive syphilis serology is suggestive of gastric infection. D, Silver stain for spirochetes demonstrates multiple organisms.

E, Hyperpigmented lesions on the hands (E1) and feet (E2) are typical for secondary syphilis.

Figure 3.21 FOCAL CYTOMEGALOVIRUS GASTRITIS

Multiple round, erythematous, raised lesions in the gastric body and antrum. The remainder of the antrum and body is normal.

Figure 3.22 CYTOMEGALOVIRUS (CMV) GASTRITIS

A, Patchy subepithelial hemorrhage in the peripyloric area. B, Multiple focal areas of subepithelial hemorrhage in a “halo” pattern.

C1, Numerous inclusions typical for CMV. C2, High-power view shows many intranuclear inclusions.

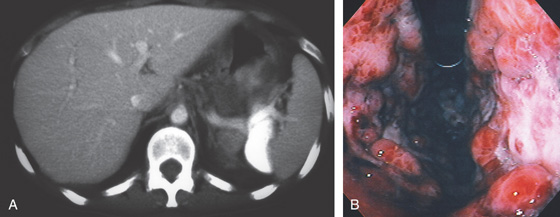

Figure 3.23 DIFFUSE SEVERE CYTOMEGALOVIRUS GASTRITIS

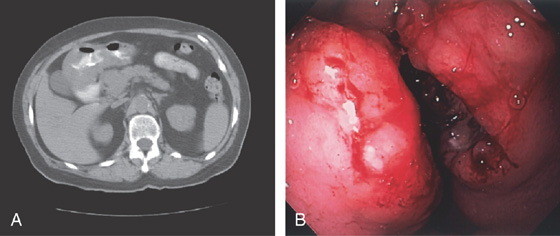

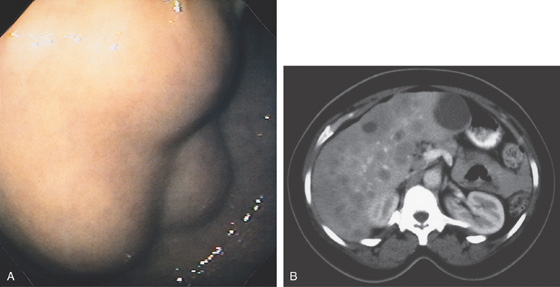

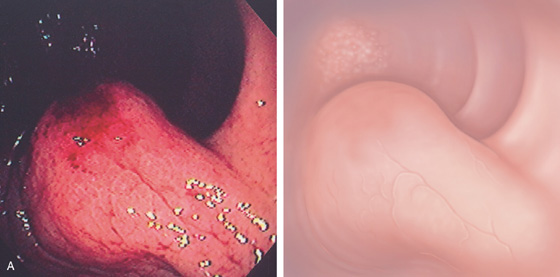

A, The stomach wall is markedly thickened, with hypodense areas suggesting necrosis. B, Retroflex view demonstrates nodularity and subepithelial hemorrhage. Diffuse ulceration is seen on the lesser curve.

C1, Marked edema and hemorrhage are present in the lamina propria. The pronounced edema produces the striking nodularity and areae gastricae pattern. C2, Multiple intranuclear inclusions characteristic of cytomegalovirus cytopathic effect.

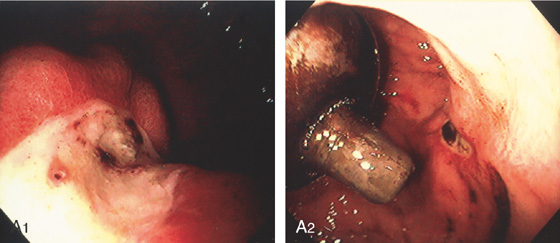

Figure 3.24 CYTOMEGALOVIRUS ULCER

Well-circumscribed, clean-based ulcer in the posterior antrum. The surrounding mucosa is normal.

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Cytomegalovirus Ulcer (Figure 3.24)

Peptic ulcer

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID)-induced ulcer

Ischemia caused by vasculitis

Malignancy

Other infections

Figure 3.25 CYTOMEGALOVIRUS ANTRAL ULCER

Large, deep ulcer. The pylorus is seen at the top left, indicating the depth of the lesion.

Figure 3.26 MYCOBACTERIUM AVIUM COMPLEX GASTRITIS

Diffuse gastritis with petechial hemorrhages and a well-circumscribed, small nodular lesion with central erosion.

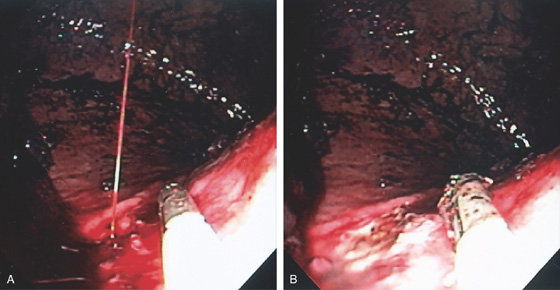

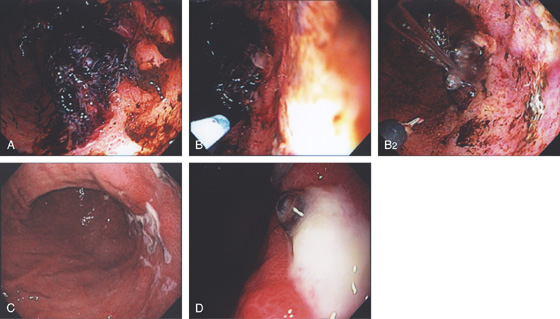

Figure 3.27 GASTRIC MUCORMYCOSIS

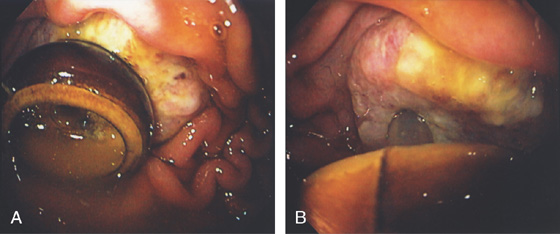

A, Erosion and exudate of the gastric antrum with a dark hue to the mucosa. A feeding tube is present.

B1, B2, Multiple fungal forms in the submucosa.

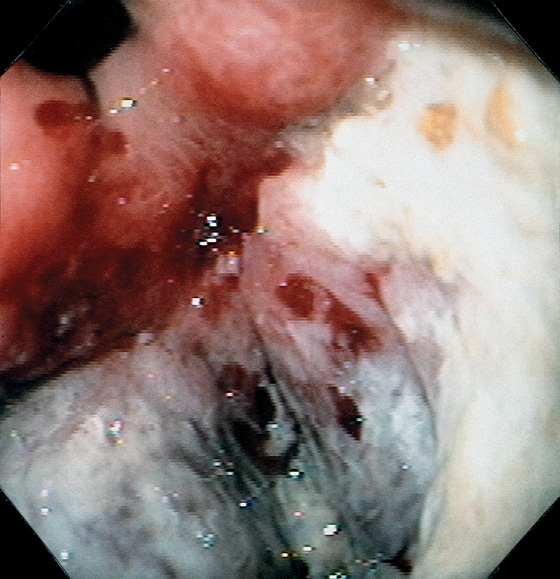

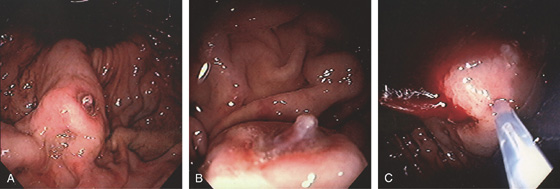

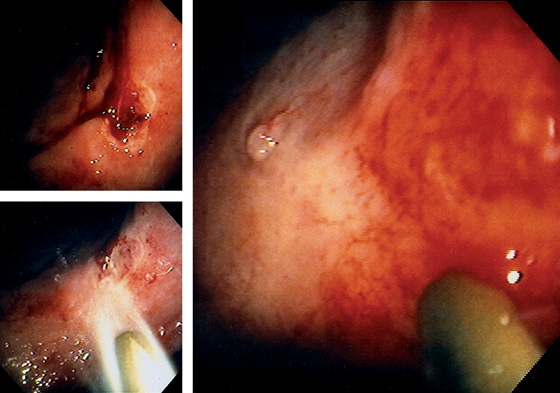

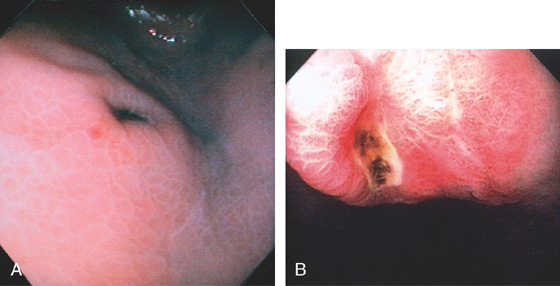

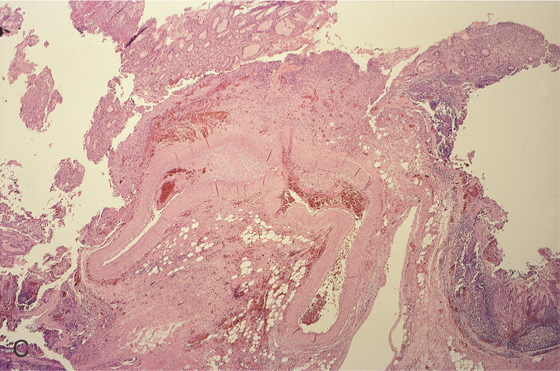

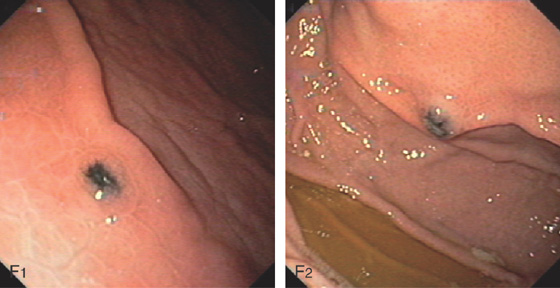

Figure 3.28 ANISAKIASIS

Single larva entering the gastric mucosa with focal area of old bleeding (A) or subepithelial hemorrhage (B). C, The larva is being removed with biopsy forceps (C1, C2).

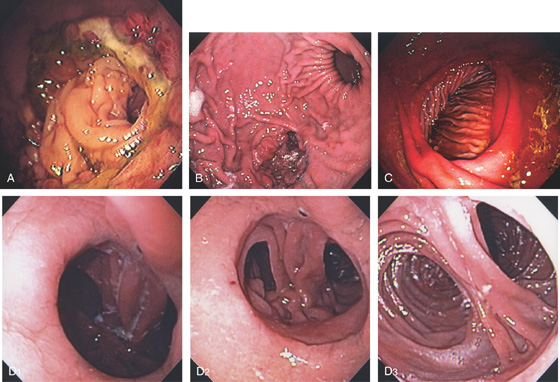

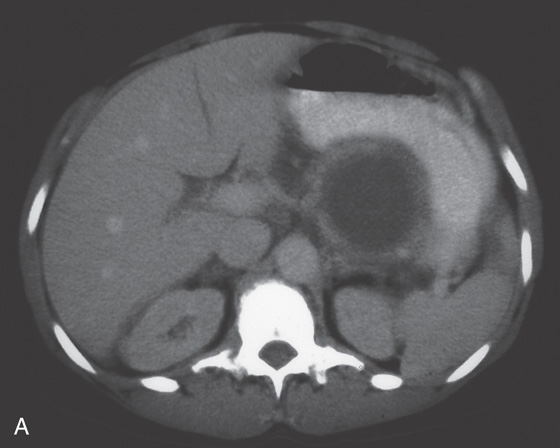

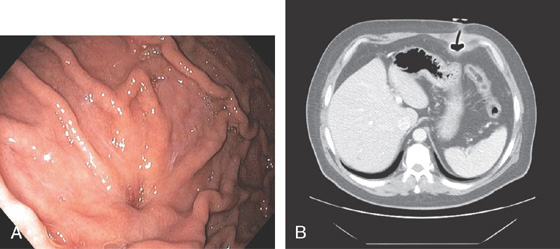

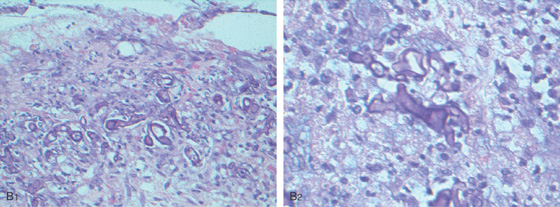

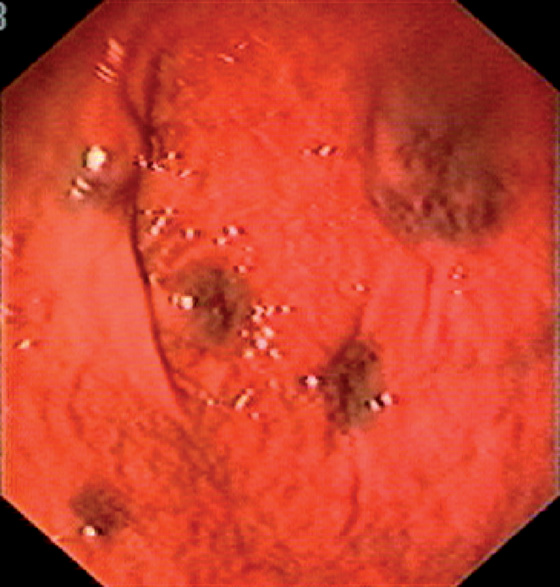

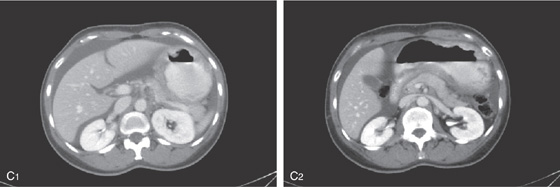

Figure 3.29 SARCOID GASTRITIS

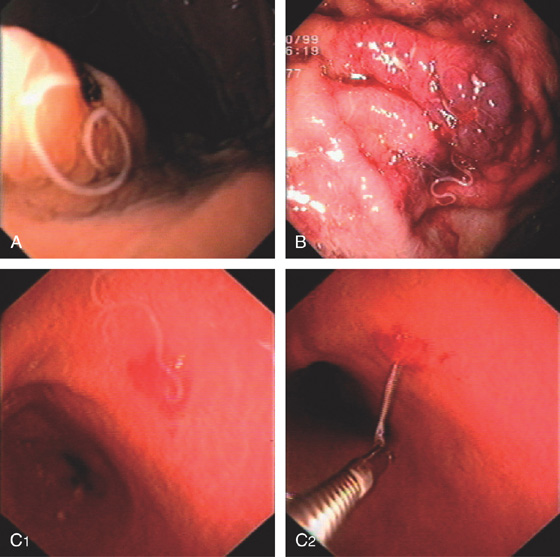

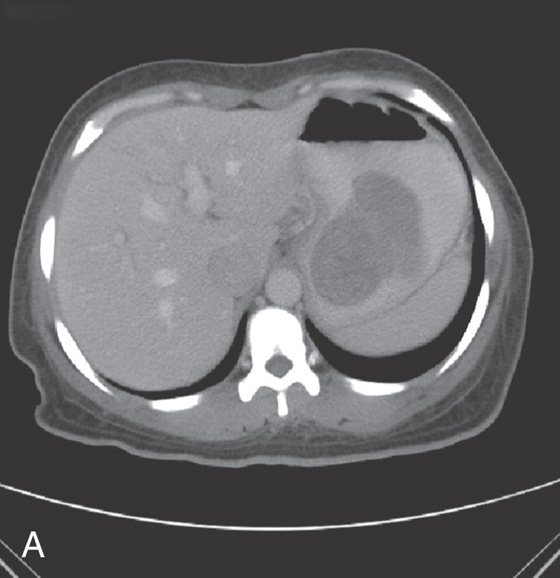

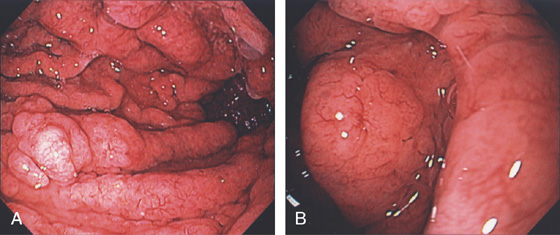

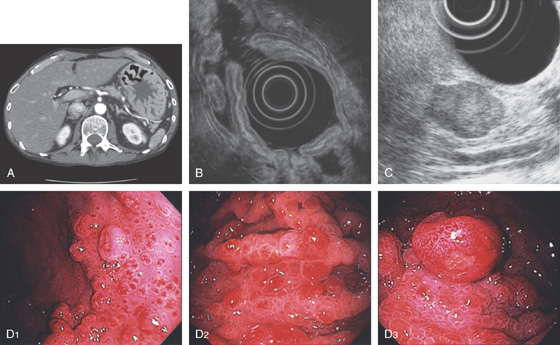

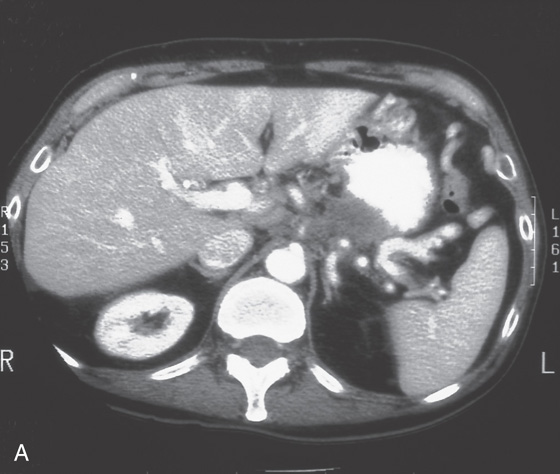

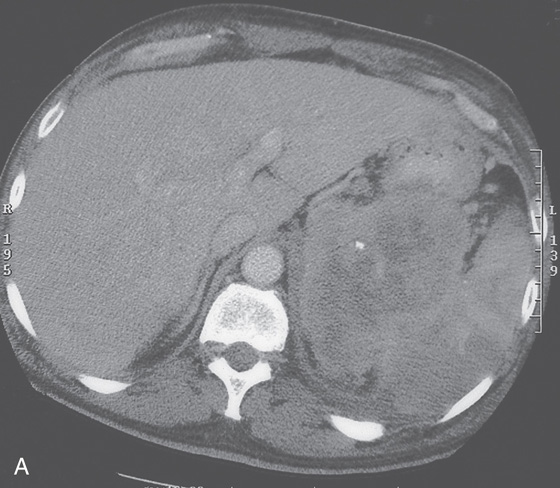

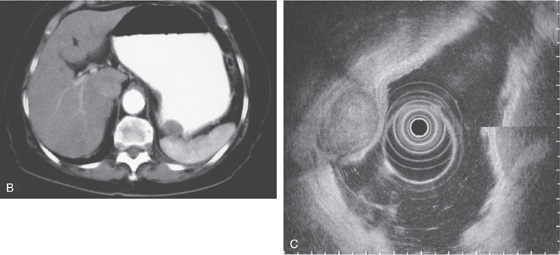

A, Marked thickening of the gastric body and antrum. Multiple retroperitoneal nodes are present. Fullness along the lateral margin of the pancreatic head and retrocaval portion of the retroperitoneum suggests adenopathy.

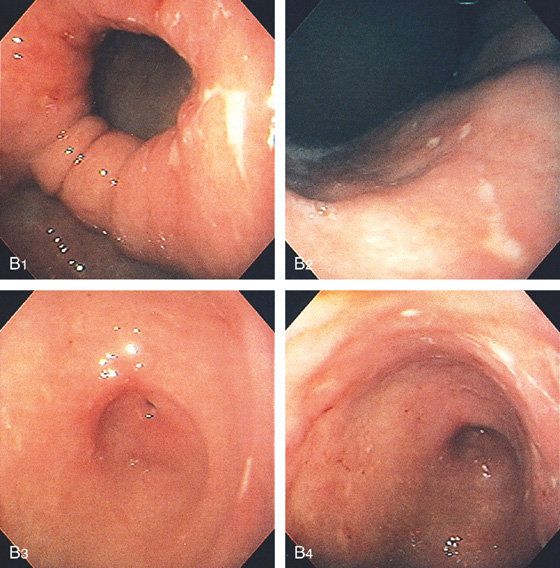

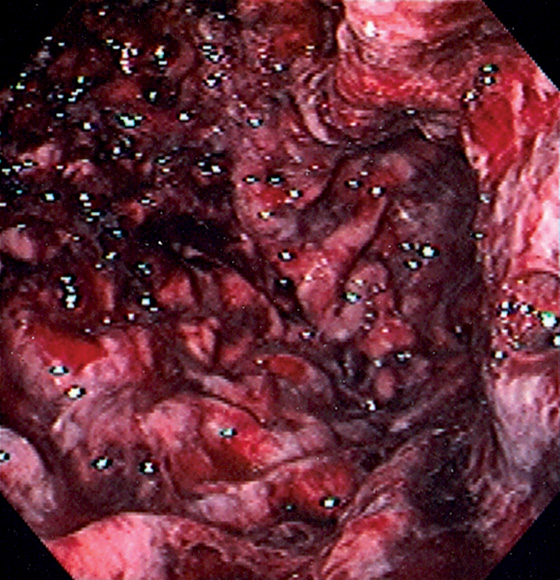

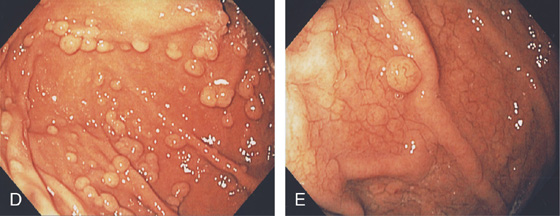

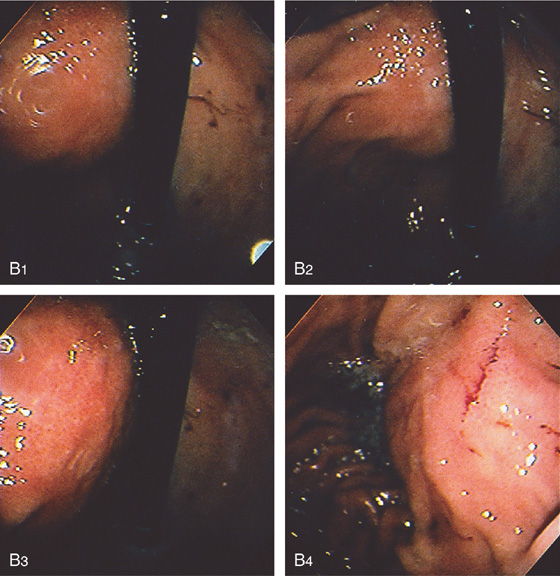

Figure 3.29 SARCOID GASTRITIS

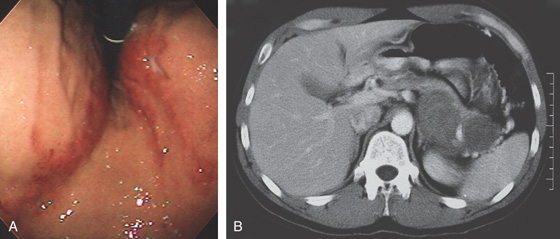

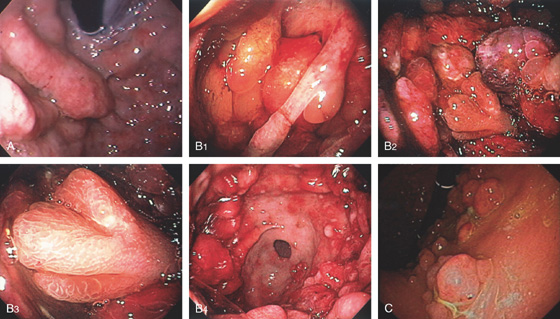

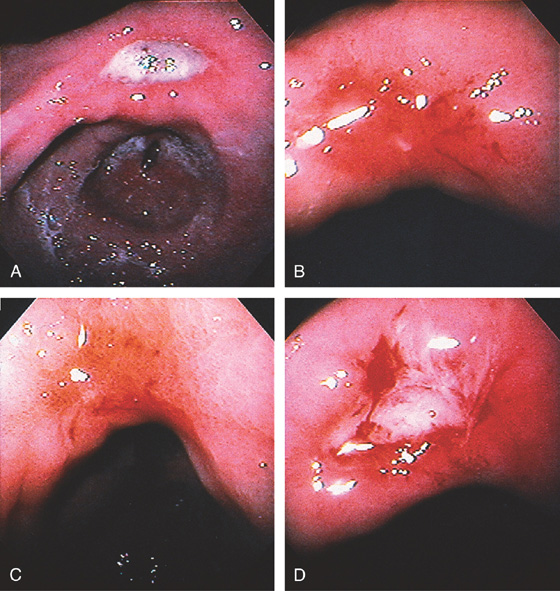

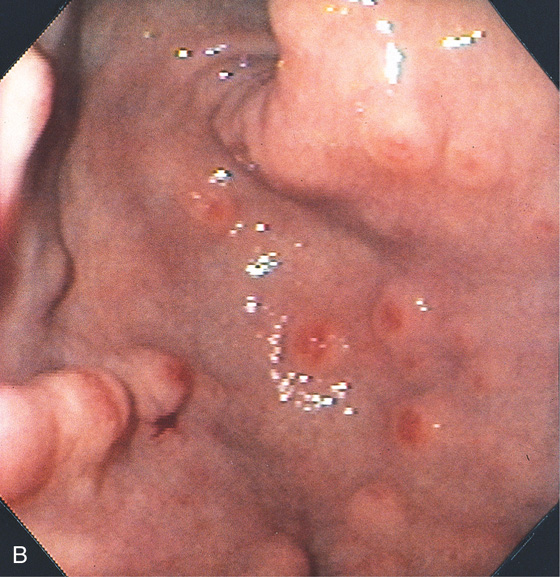

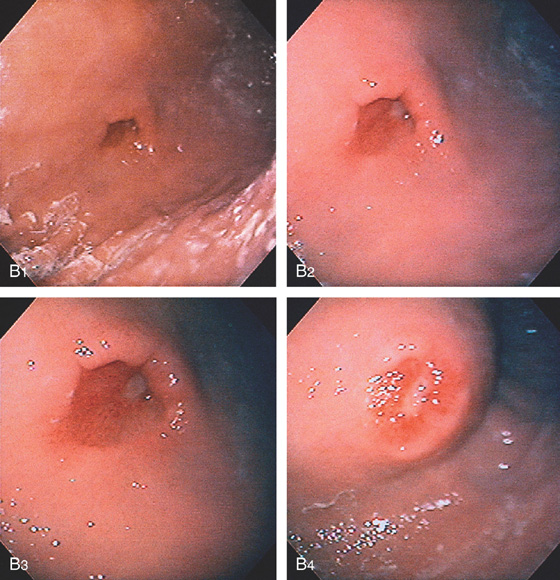

B, Multiple erosions, some having an unusual stellate appearance, in the gastric body (B1), angularis and proximal lesser curve (B2), and antrum (B3, B4). The antrum has a yellow-orange discoloration and a mottled appearance; the mucosa is friable.

C, Noncaseating granuloma in the lamina propria. Special stains for other causes of granulomatous gastritis, including mycobacterial and fungal organisms, were negative.

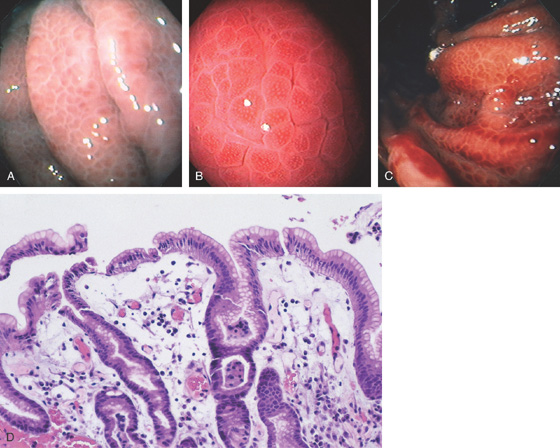

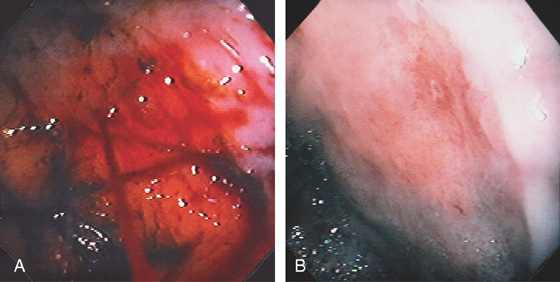

Figure 3.30 SARCOID GASTRITIS

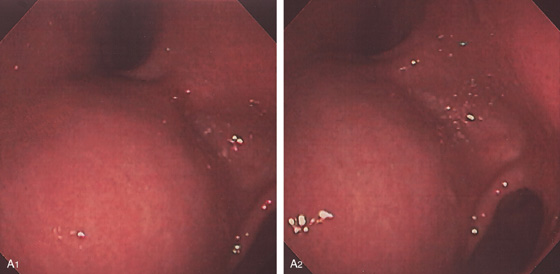

A, Nodular fold thickening of the gastric antrum, duodenal bulb, and postbulbar duodenum. B, Marked thickening of the gastric wall. C, Marked nodularity and thickening of the folds in the gastric body. D, Nodular lesions in the gastric antrum. E, The thickening of the gastric wall is limited to the mucosal layer by endoscopic ultrasonography.

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Sarcoid Gastritis (Figure 3.30)

Gastric adenocarcinoma

Lymphoma

Metastatic tumor resulting in linitis plastica

Figure 3.31 ALCOHOL-INDUCED GASTROPATHY

A, The gastric rugae are edematous, with fresh blood seen under the mucosal surface; the overlying mucosa is smooth. B, A prominent band of extravasated erythrocytes is present, associated with edema of the lamina propria. No histologic evidence of gastritis is present.

Figure 3.32 ASPIRIN-INDUCED GASTROPATHY

A, Multiple scattered petechial hemorrhages, with normal-appearing intervening mucosa. B, Subepithelial hemorrhage is present without an associated inflammatory process.

Figure 3.33 ASPIRIN-INDUCED GASTROPATHY

Multiple areas of fresh hemorrhage in the distal gastric body and antrum.

Figure 3.34 NONSTEROIDAL ANTIINFLAMMATORY DRUG (NSAID)-INDUCED EROSIVE GASTROPATHY

Multiple linear erosions surrounded by a halo of erythema in the antrum, with normal intervening mucosa. Antral disease is the typical location for NSAID-induced injury.

Figure 3.35 NONSTEROIDAL ANTIINFLAMMATORY DRUG (NSAID)-INDUCED GASTROPATHY

A, B, Multiple small antral erosions with erythematous halos.

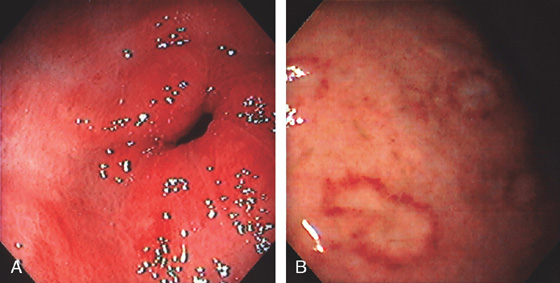

Figure 3.36 PORTAL HYPERTENSIVE GASTROPATHY

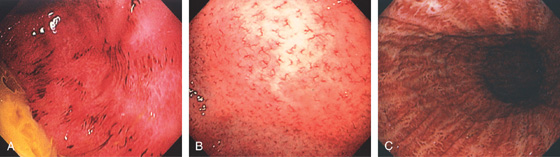

A, Mild disease is manifested by prominence of the areae gastricae, with areas of erythema and subepithelial hemorrhage. This appearance is not pathognomonic but may be noted with other disorders inducing mucosal edema, such as Helicobacter pylori gastritis. B, Marked prominence of the areae gastricae. C, Severe gastropathy with diffuse subepithelial hemorrhage in a snakeskin pattern. D, Prominent edema of the lamina propria with multiple congested blood vessels. No histologic evidence of gastritis is seen.

Figure 3.37 THROMBOTIC THROMBOCYTOPENIC PURPURA

Multiple areas of subepithelial hemorrhage throughout the gastric body.

Figure 3.38 NASOGASTRIC TUBE TRAUMA

A, Multiple well-circumscribed, hemorrhagic lesions extending down the gastric body to the antrum. B, The reddish color resembles ectasias. C, With progression, erosions may result, and then ultimately ulcers (D).

Figure 3.39 GRAFT-VERSUS-HOST DISEASE

A, Normal-appearing gastric antrum. Biopsies confirmed mild graft-versus-host disease. The mucosa may appear normal in mild disease, emphasizing the importance of mucosal biopsies. B, Marked erythema of the gastric body with multiple erosions. C, Sloughing of the antral mucosa leaving a shiny erythematous appearance.

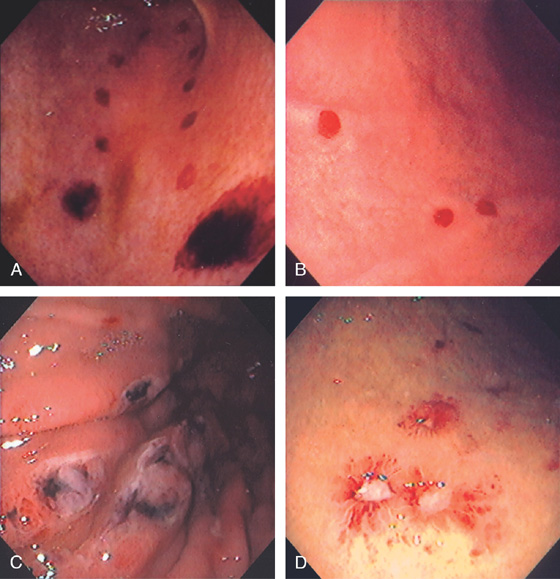

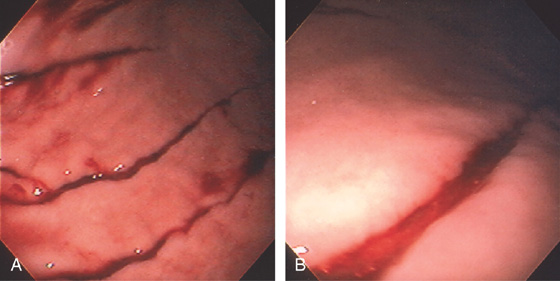

Figure 3.40 GASTRIC TEAR

This fresh tear occurred during endoscopy in a patient with pronounced gastric atrophy. This could occur from the endoscope in addition to air insufflation and retching.

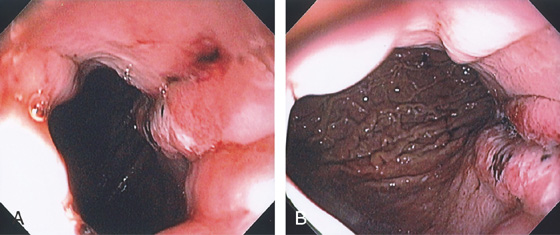

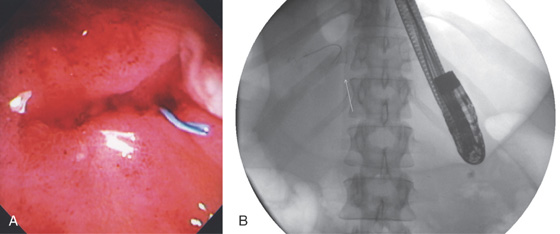

Figure 3.41 GASTRIC MALLORY-WEISS TEAR

A, Tear begins distal to the gastroesophageal (GE) junction. B, Note the extent of the lesion down the lesser curvature.

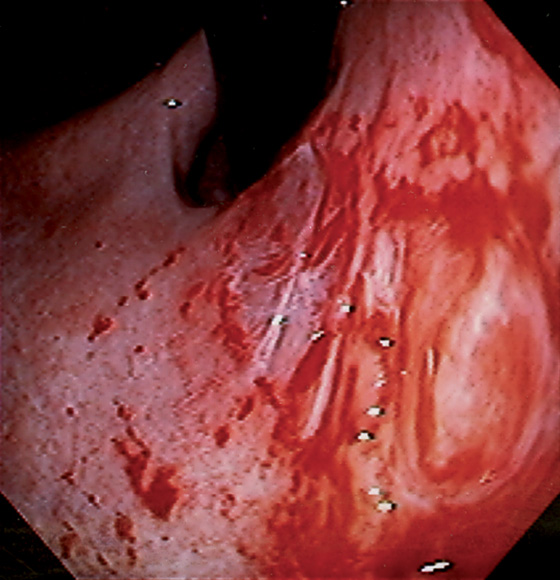

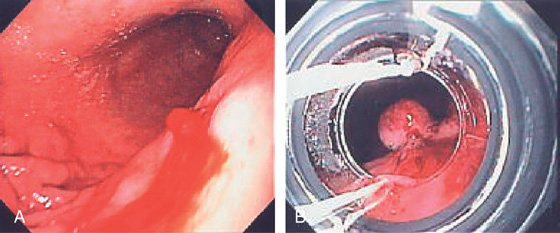

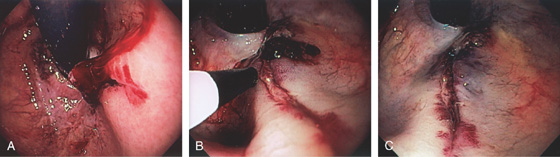

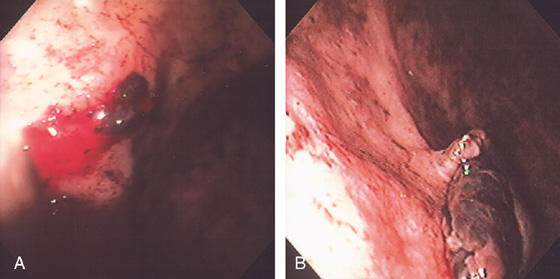

Figure 3.42 BLEEDING GASTRIC MALLORY-WEISS TEAR

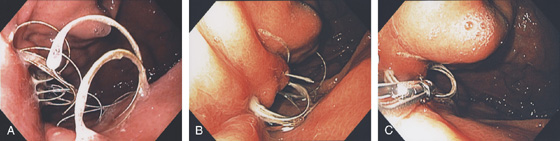

A, Retroflex view shows active bleeding from a linear lesion just distal to the GE junction. B, Epinephrine injection results in blanching of the mucosa. C, Blanching is apparent around the tear with resultant hemostasis.

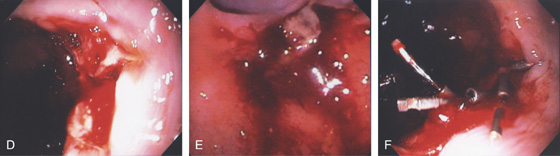

Figure 3.42 BLEEDING GASTRIC MALLORY-WEISS TEAR CLIPPING OF A GASTRIC MALLORY-WEISS TEAR

D, E, Tear just below a ring at the gastroesophageal junction. F, Clips applied to the lesion resulting in hemostasis.

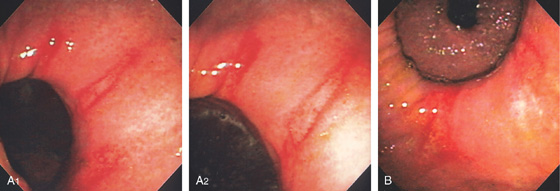

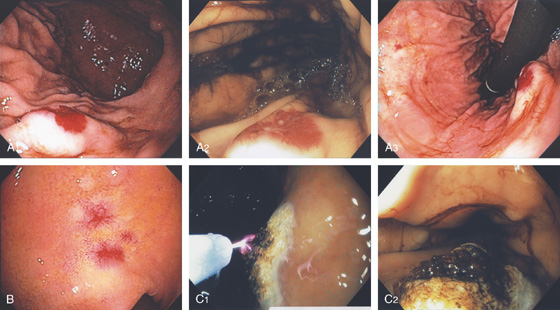

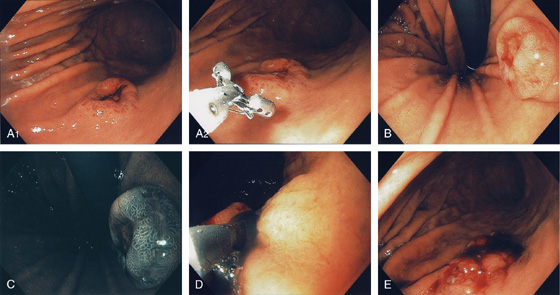

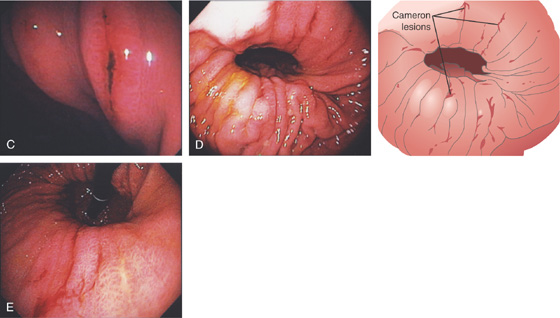

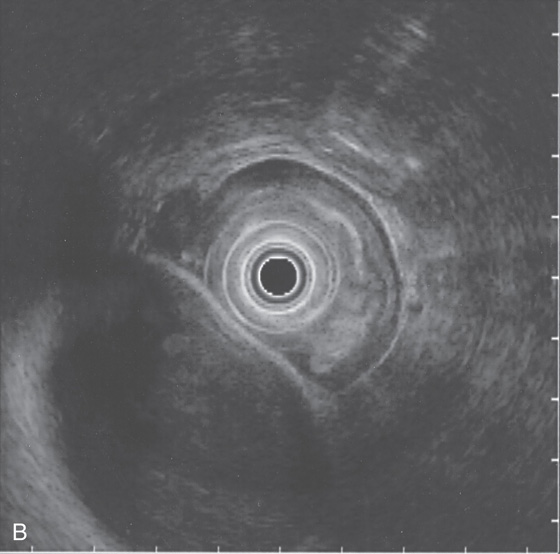

Figure 3.43 CAMERON LESIONS

Multiple erosions straddle a large hiatal hernia as shown on antegrade (A1, A2) and retrograde (B) views.

C, Several lesions on the gastric folds, one of which has a linear black eschar. Multiple linear areas of fresh hemorrhage on the diaphragmatic hiatus on antegrade (D) and retrograde (E) views.

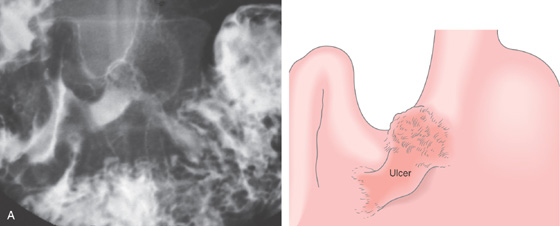

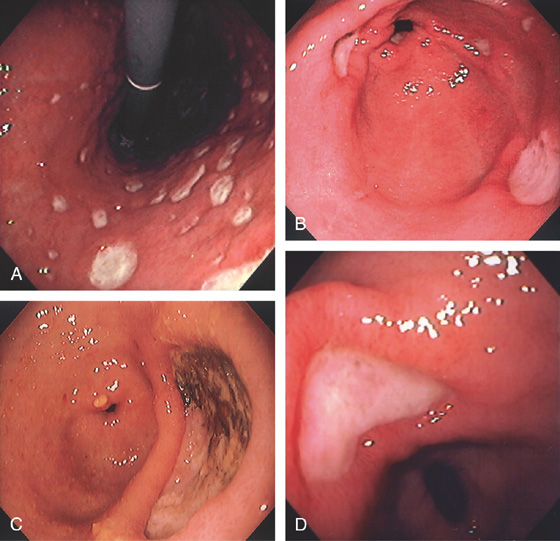

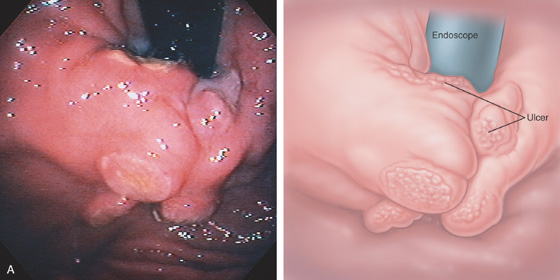

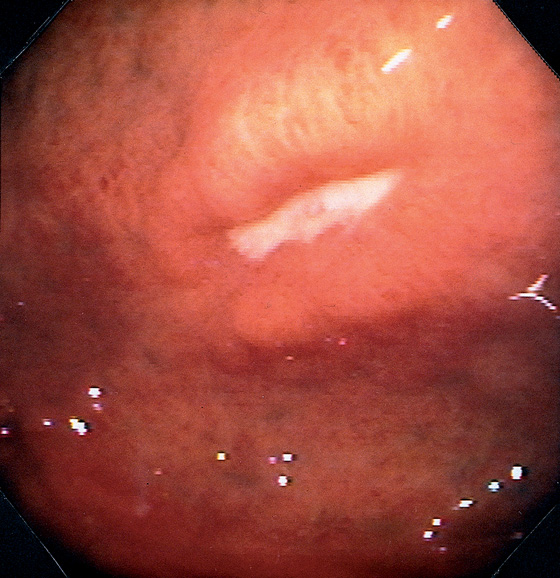

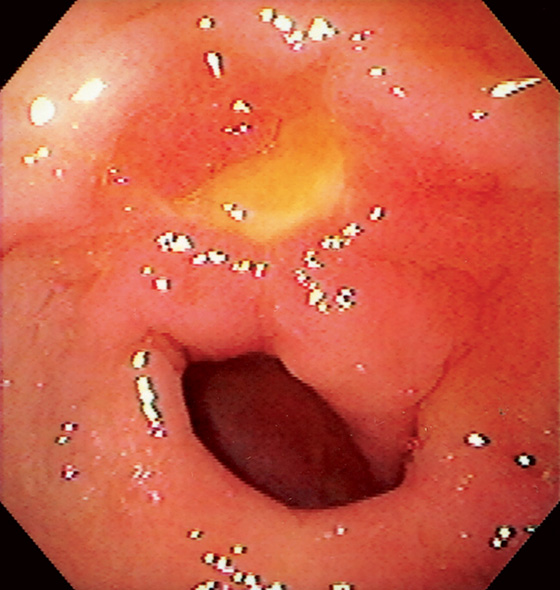

Figure 3.44 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

Linear ulceration of the gastric cardia. The surrounding mucosa is erythematous, with subepithelial hemorrhages.

Figure 3.45 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

Ulcer in the fundus with an elevated appearance.

Figure 3.46 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

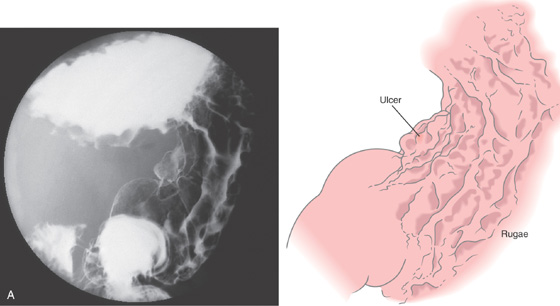

A, Elbow-shaped ulceration along the lesser curvature. The proximal portion of the ulcer has air contrast, whereas the distal portion has barium pooling.

B, The shape of the large ulceration on the angularis corresponds to the radiograph. Additional ulcerations are present anteriorly. Multiple black spots (stigmata of hemorrhage) are present in the ulcer base, despite the absence of clinical bleeding.

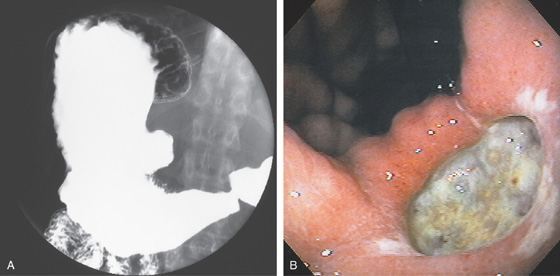

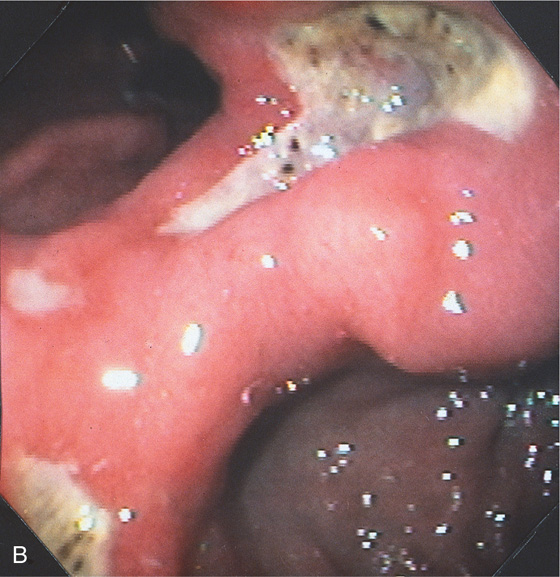

Figure 3.47 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

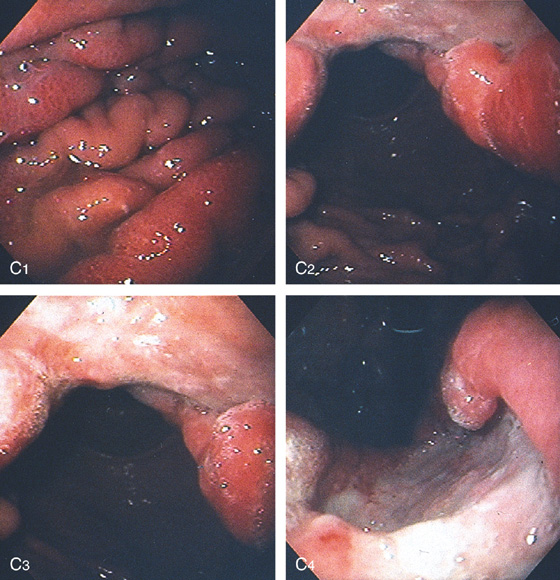

A, Ulcer on the angularis projecting away from the gastric lumen, suggesting a benign lesion. B, Large benign-appearing ulcer on the angularis. Exudate covers the base. The ulcer has a symmetrical punched-out appearance, and no abnormal-appearing rugal folds appear around the lesion.

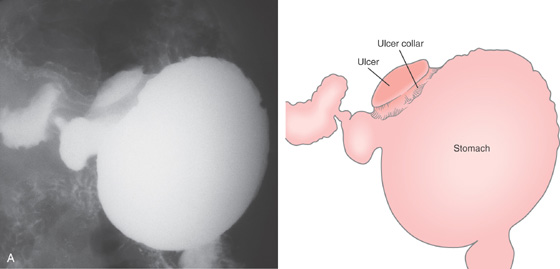

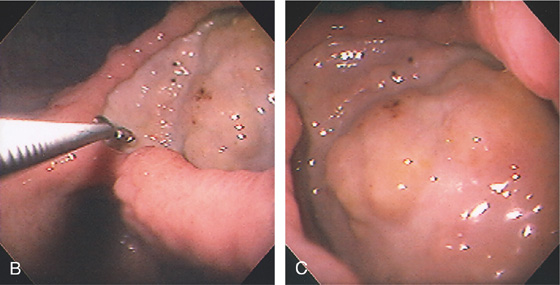

Figure 3.48 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

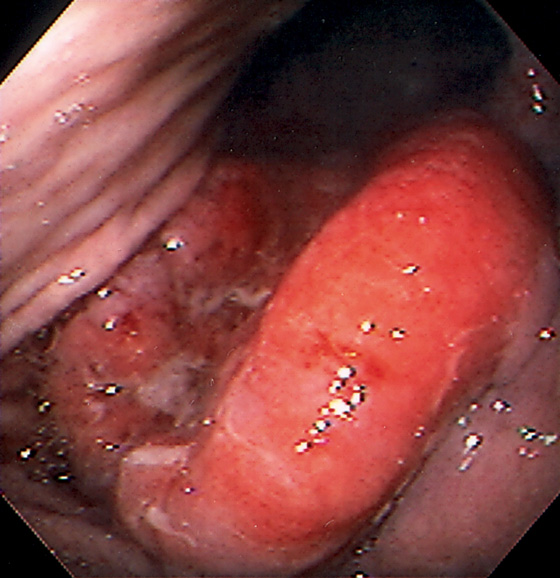

A, Large ulcer projecting off the lesser curve at the angularis. An ulcer collar is present, suggesting a benign lesion.

B, Large, well-circumscribed ulcer on the angularis seen by retroflexion. The size of the ulcer is evident by comparison with the open biopsy forceps (6 mm in width). C, Close-up shows the size and depth of the lesion. The base has a nodular appearance suggestive of involvement of surrounding abdominal structures.

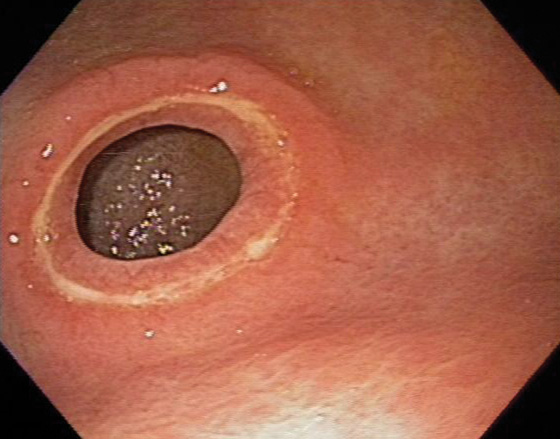

Figure 3.49 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

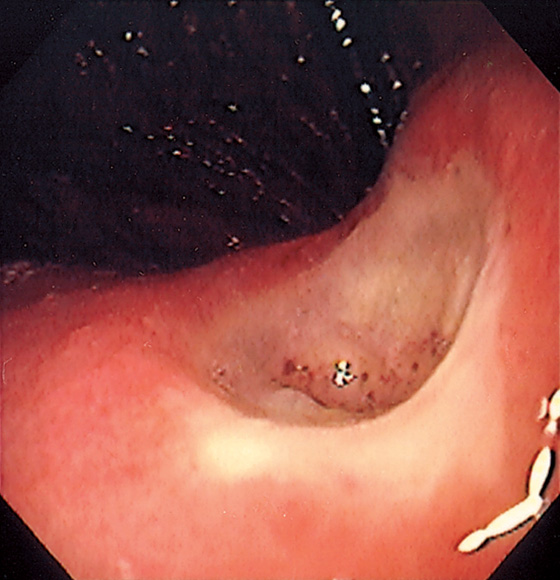

Well-circumscribed ulcer of moderate depth on the angularis. The borders are smooth and the ulcer is relatively symmetrical, all of which are features suggestive of a benign as compared with a malignant ulcer.

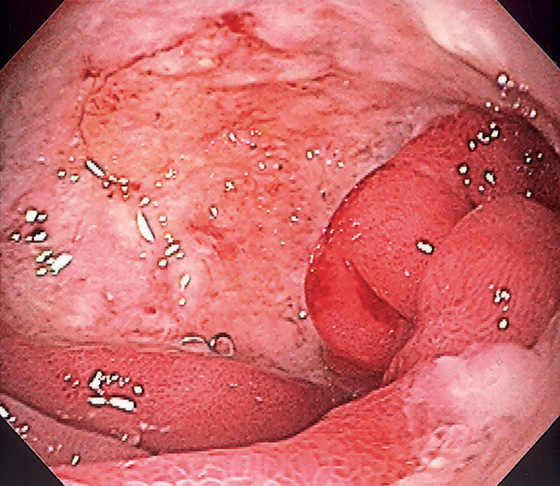

Figure 3.50 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

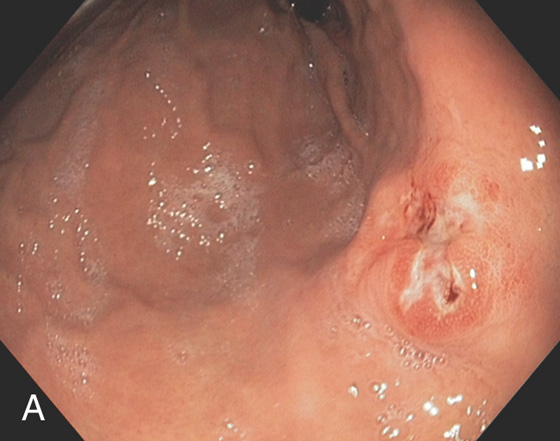

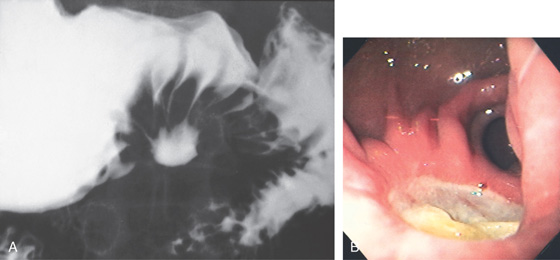

A, Benign-appearing gastric ulcer as demonstrated by the well-circumscribed nature of the barium collection (ulcer), with multiple smooth folds radiating to the ulcer. A smooth, round, homogeneous mound of edema surrounding the crater, with smooth radiating folds extending all the way to the crater, suggests a benign ulcer. Other signs of a benign ulcer include Hampton’s line or an ulcer collar and projection beyond the lumen. B, Large, well-circumscribed antral ulceration, with folds radiating to the ulcer base.

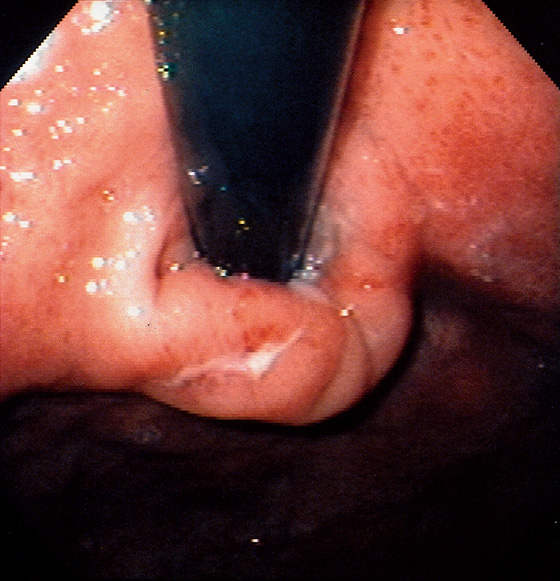

Figure 3.51 PERIPYLORIC ULCER

Circumferential ulceration surrounds the pylorus.

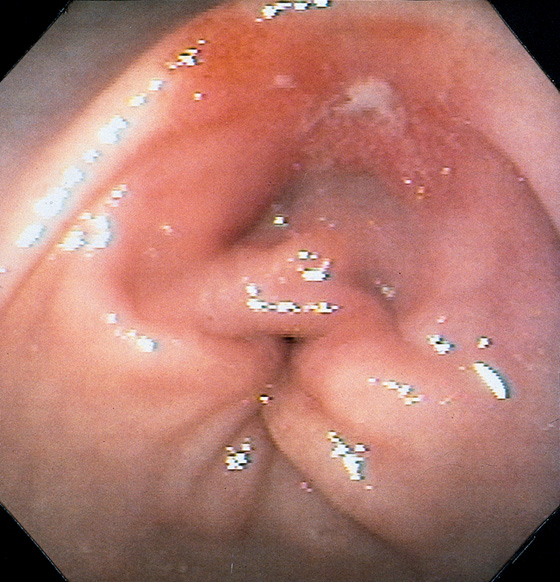

Figure 3.52 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

Small prepyloric ulceration, with surrounding erythema superior and posterior to the pylorus. There is cicatrization of the stomach toward the ulceration.

Figure 3.53 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

Bile-stained peripyloric ulcer.

Figure 3.54 ANTRAL ULCER

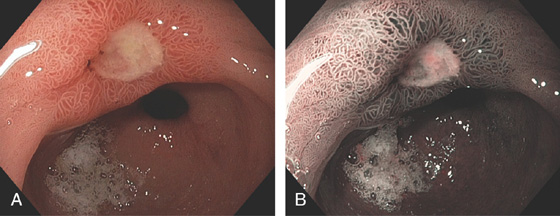

Well-circumscribed, benign-appearing ulcer in the antrum anteriorly on high-resolution (A) and narrow band imaging (B).

Figure 3.55 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

Large deep ulceration at the pylorus (A, B).

Figure 3.56 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

Large ulceration with a heaped-up appearance in the distal gastric body. The raised appearance is unusual and suggests primary or metastatic malignancy. Follow-up endoscopy after therapy showed ulcer healing.

Benign Gastric Ulcer (Figure 3.56)

Adenocarcinoma

Metastatic carcinoma

Melanoma

Breast carcinoma

Lung carcinoma

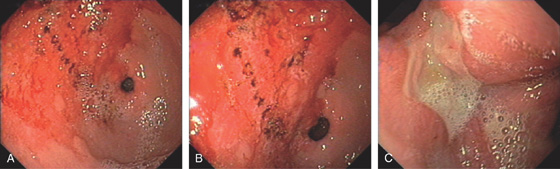

Figure 3.57 BENIGN GASTRIC ULCER

Deep, well-circumscribed, benign-appearing ulcer on the angularis (A). One month after standard ulcer therapy, the ulceration has almost completely healed; there is a small central erosion, deformity, and diffuse erythema and friability (B). After 2 months of therapy, complete healing is seen; friability is still present (C). One month after discontinuation of therapy, the ulcer has recurred in the same location and with endoscopic characteristics similar to those of the initial ulcer (D).

Figure 3.58 BENIGN ULCER IN GASTRIC POUCH

Hemicircumferential ulceration in a small gastric pouch after gastric bypass.

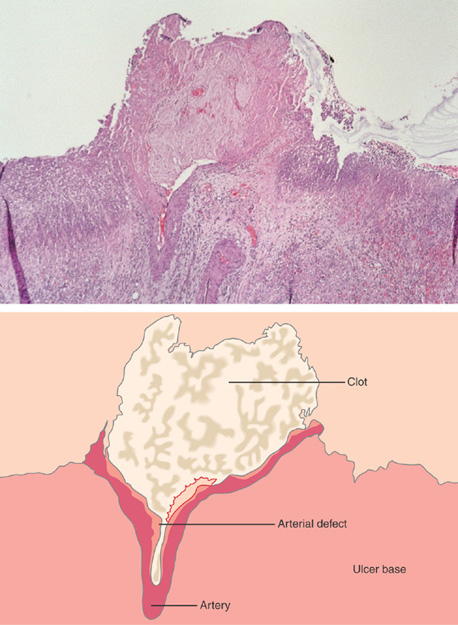

Figure 3.59 HISTOLOGY OF AN ULCER BASE

Characteristic histopathologic changes of an ulcer base, including acute and chronic inflammatory cells, fibroplasia, and neovascularization. Careful examination must be performed to differentiate reactive atypia from neoplasia in this area.

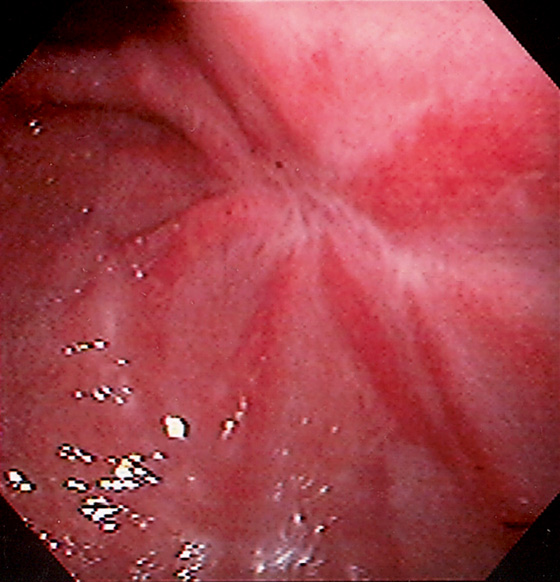

Figure 3.60 ULCER SCAR

Retraction of the mucosa with radiating folds and erythema typical for an area of prior large ulceration.

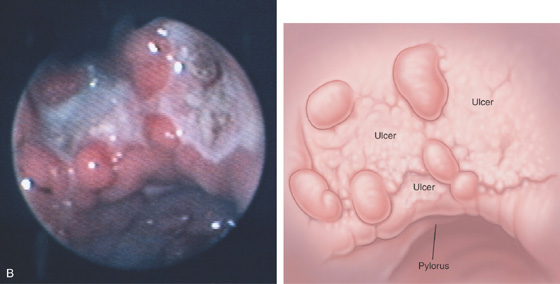

Figure 3.61 NONSTEROIDAL ANTIINFLAMMATORY DRUG (NSAID)-INDUCED GASTRIC ULCERS

A, Numerous well-circumscribed ulcers involving the gastric body and fundus seen on retroflexion. B, Multiple well-circumscribed ulcerations of the antrum and pyloric canal. C, Solitary chronic-appearing ulcer of moderate depth on the posterior wall of the antrum. Note the xanthomatous lesion at the pylorus. D, Large, triangular-shaped ulcer in the distal antrum.

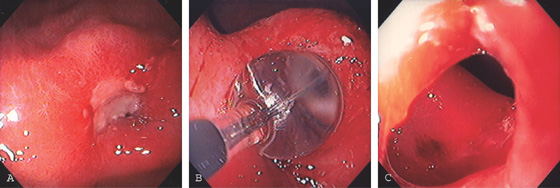

Figure 3.62 PYLORIC STENOSIS CAUSED BY ULCER

A, Exudate and edema at the pylorus. The opening is not visible. B, A balloon was inflated across the ulceration. C, The luminal caliber is now much improved.

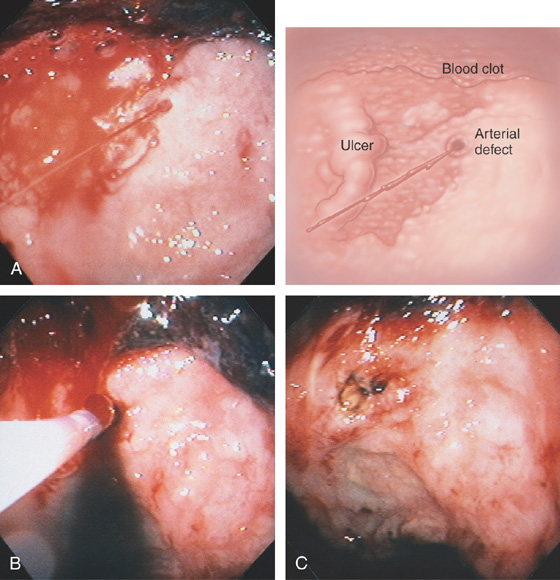

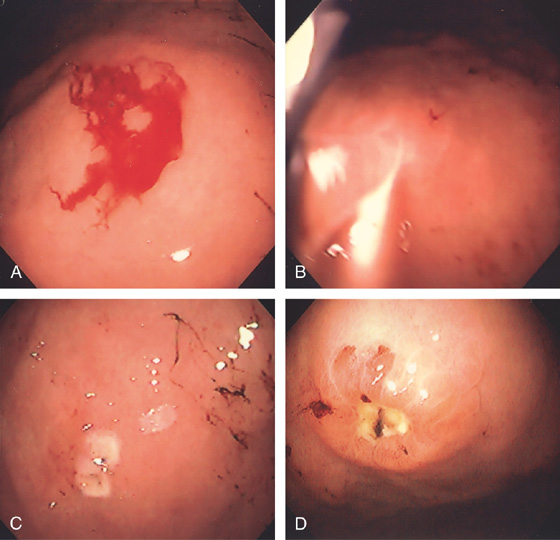

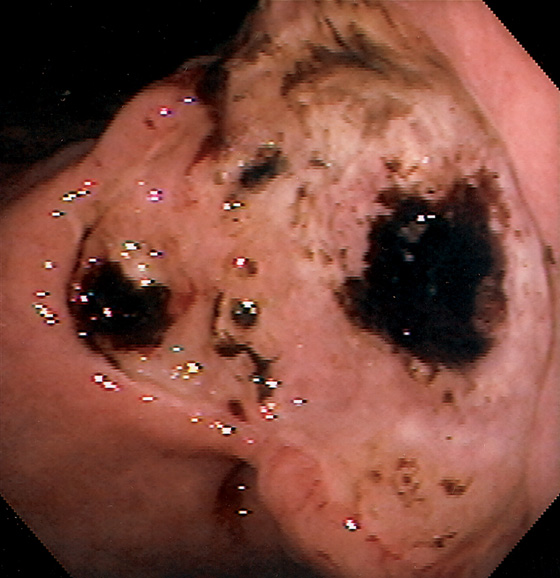

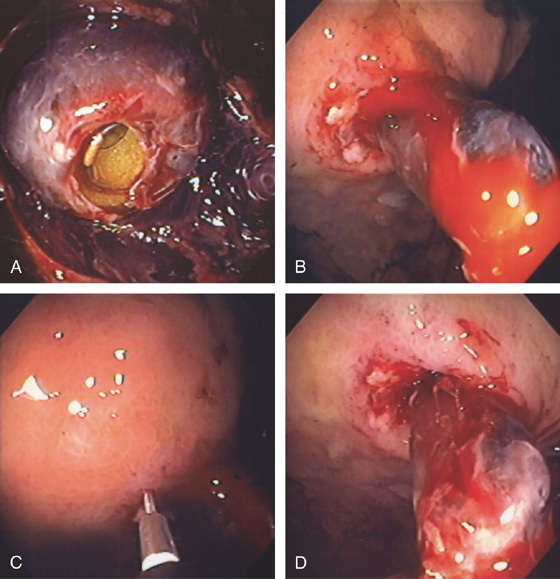

Figure 3.63 BLEEDING GASTRIC ULCER

A, Large gastric ulcer with a central arterial defect. Blood is spurting in a pulsatile fashion, characteristic of an arterial bleeding source. B, A heater probe is applied with firm pressure to the defect, causing cessation of bleeding. C, After multiple pulses of energy and washing, the defect is coagulated, as represented by the black areas. With washing, the large size of the ulceration is evident.

Figure 3.64 BLEEDING GASTRIC ULCER

A, Arterial jet pulsating from an area in the proximal gastric body. The heater probe is alongside the lesion. B, Thermal therapy was then applied to the area, resulting in a black eschar and hemostasis.

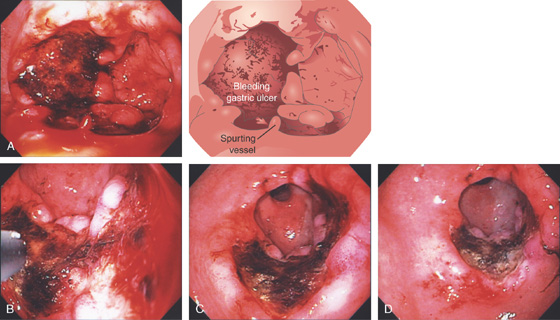

Figure 3.65 BLEEDING GASTRIC ULCER

A, Large ulceration with fresh bleeding and an actively pulsating jet. B, Epinephrine was injected and the heater probe used to ablate the area, resulting in a large eschar (C). Now that the bleeding has ceased, the extensiveness of the ulcer can be identified (D).

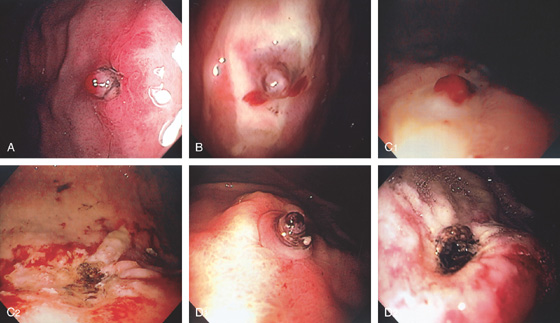

Figure 3.66 GASTRIC ULCER WITH VISIBLE VESSEL

A, Large ulcer on the angularis with central raised lesion. B, Fleshy visible vessel in the center of the ulcer.

Figure 3.67 GASTRIC ULCER WITH VISIBLE VESSEL

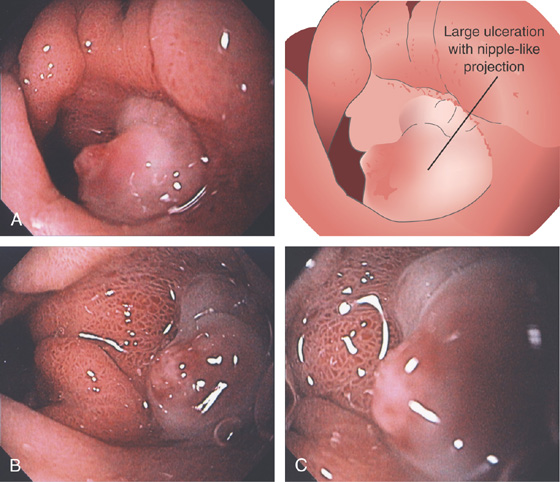

A, Nipple-like projection emanating from a small mucosal defect. B, Fleshy nipple-like projection from a superficial ulceration. C1, Linear ulcer with raised area with reddish covering. C2, After thermal therapy, the vessel has been obliterated, leaving a black eschar with depth. D1, Dark nipple-like projection of the gastric body. D2, Thermal therapy obliterated the lesion, resulting in a deep black eschar.

E, A small gastric ulcer displays a nipple-like projection, which has all the appearance of an artery. F1, F2, Large visible vessel with associated ulcer at a narrowed gastrojejunal anastomosis in a patient with a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Figure 3.68 BLEEDING ANTRAL ULCER WITH VISIBLE VESSEL

A-C, Large ulceration in the posterior antrum with a nipple-like projection emanating from the base of the lesion. Because of recurrent bleeding, surgery was performed demonstrating that the visible vessel was a middle colic artery, a branch of the superior pancreaticoduodenal arcade.

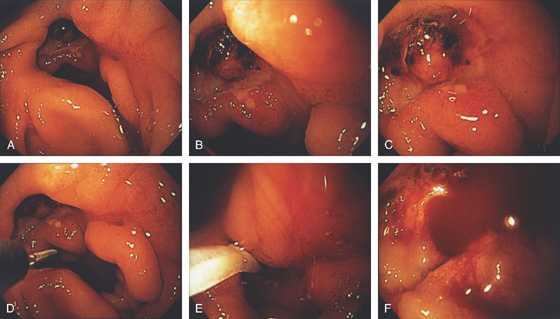

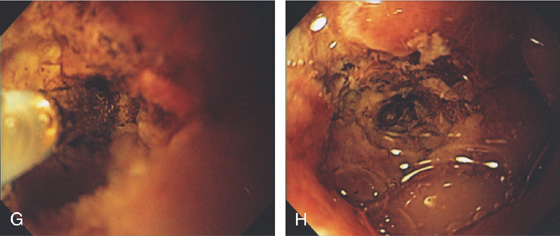

Figure 3.69 PREPYLORIC ULCER WITH VISIBLE VESSEL

A-C, Large, deep ulceration in the pyloric ring. Black eschar is shown, as well as a nipple-like projection. D, Epinephrine is first injected, (E, F) followed by multiple pulses of the 10-French heater probe precipitating some bleeding.

G, H, The visible vessel has been ablated, resulting in a black eschar.

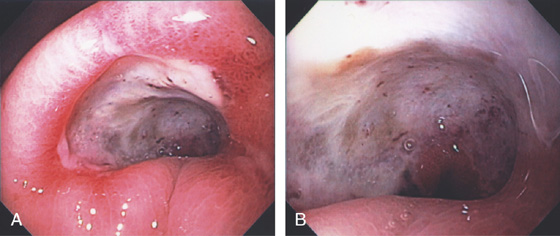

Figure 3.70 MALIGNANT GASTRIC ULCER WITH VISIBLE VESSEL

Visible vessel at the inferior margin of a malignant gastric ulcer. The gastric ulcer has large, heaped-up margins.

Figure 3.71 BLEEDING GASTRIC ULCER WITH VISIBLE VESSEL

Gastric ulcer is actively oozing (top left). With washing, the bleeding area is cleaned of blood (bottom left). A transparent piece of fleshy tissue is seen, representing a visible vessel. Such a transparent visible vessel may have the highest incidence of rebleeding.

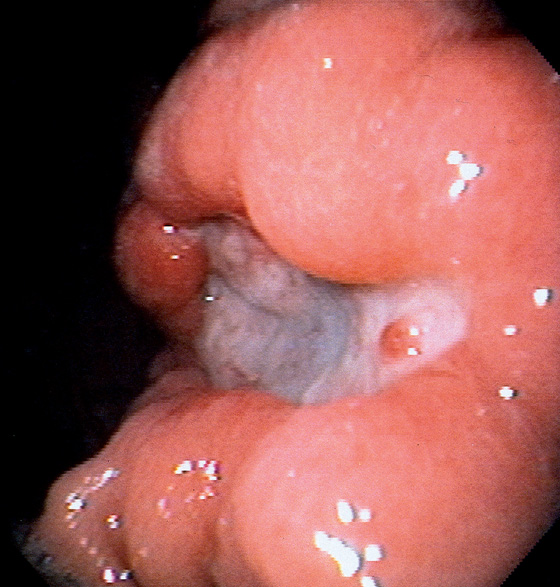

Figure 3.72 HISTOPATHOLOGY OF A VISIBLE VESSEL

The vessel wall is ruptured at the luminal surface and is filled by thrombus. The surrounding tissue shows extensive ulceration.

Figure 3.73 BLEEDING GASTRIC ULCER

Large, well-circumscribed ulcer on the angularis, with blood clot and area of active oozing. The open biopsy forceps (6 mm) documents ulcer size.

Figure 3.74 GASTRIC ULCER WITH CLOTS

Giant gastric ulcer on the angularis with multiple areas of adherent clot.

Figure 3.75 GASTRIC ULCER WITH BLOOD CLOT

A, Gastric ulcer with large blood clot adherent to a focal point. B, Rebleeding occurred 1 week later. The clot is now gone, and the bleeding point is evident. Debris can be seen adherent to the ulcer base. C1, A blood clot is seen at the edge of a benign gastric ulcer. C2, Appearance of the lesion after epinephrine injection.

Figure 3.76 SMALL GASTRIC ULCER WITH FRESH BLOOD CLOT

A, Long blood clot emanating from a small area at the site of a Billroth-I anastomosis. Biopsies were recently taken from this site. B, After washing, a small ulcer, created by the mucosal biopsy, with an area of active bleeding is apparent.

Figure 3.77 GASTRIC ULCER WITH BLOOD CLOT

A, Large gastric ulcer on the angularis with focal overlying clot. B1, B2, After clot removal by washing, a visible vessel is exposed.

Figure 3.78 GASTRIC ULCER WITH ADHERENT BLOOD CLOT

A, Large blood clot on an ulceration in the midgastric body posteriorly near the angularis. The blood clot could not be removed. B, Large-volume epinephrine was injected (B1, B2). With washing, the lesion is now more visible. C, Forty-eight hours later, second look endoscopy is performed showing that the blood clot is now gone with shallow ulceration, and at one of the lesions an area suggestive of a visible vessel is present (D).

Figure 3.79 PERIPYLORIC ULCER WITH RED SPOT

Large ulcer with a central flat red spot. There is associated edema, with a small erosion near the ulcer.

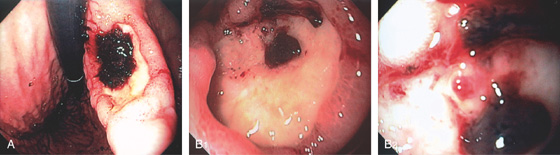

Figure 3.80 GASTRIC ULCER WITH BLACK BASE

A, Raised gastric ulcer with a black base. The surrounding mucosa has a prominent areae gastricae pattern. B, Deep ulcer with black base in the gastric body.

Figure 3.81 GASTRIC ULCER WITH SPOTS

A, Small gastric ulcer with a linear red spot. B, Well-circumscribed, small gastric ulcer with both black and red spots. C, Large gastric ulcer on the angularis with multiple black spots.

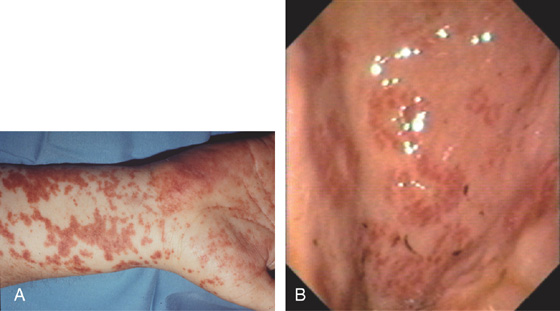

Figure 3.82 HENOCH-SCHÖNLEIN PURPURA

A, Diffuse purpuric lesions of the skin. B, Focal subepithelial hemorrhage in the gastric antrum. (A courtesy P. Redondo, MD, Pamplona, Spain.)

Figure 3.83 BLUE RUBBER BLEB NEVUS SYNDROME

Multiple subepithelial blebs in the proximal stomach. This patient had concomitant esophageal (see Figure 2.148) and colonic lesions.

Figure 3.84 DIEULAFOY LESION

A, Arterial bleeding (spurting) just distal to the gastroesophageal junction. B, The bleeding point was a small defect without endoscopic evidence of ulceration.

Figure 3.85 DIEULAFOY LESION

A, Active arterial bleeding from a pinpoint area along the lesser curvature. B, Band applied to lesion.

Figure 3.86 DIEULAFOY LESION

A, Active bleeding from a small lesion in the gastric fundus. B, Bleeding spontaneously stopped, and with washing a visible vessel and blood clot are apparent.

C, Histopathology of the lesion shows a large tortuous artery at the mucosal surface.

Figure 3.87 STRESS GASTROPATHY

Diffuse hemorrhage of the gastric body after a prolonged episode of hypotension.

Figure 3.88 GASTRIC ISCHEMIA

Diffuse ulceration of the gastric body caused by a gastric volvulus.

Figure 3.89 ISCHEMIC GASTROPATHY

A, B, Well-demarcated giant ulcer in the antrum with erythema and fresh hemorrhage. Note the geographic distribution. This patient had intraarterial chemotherapy for hepatic metastases. C, Nine months later, follow-up endoscopy shows a well-defined ulcer in the ischemic area.

Figure 3.90 VASCULAR ECTASIA

A1, A2, Large ectasia in the gastric body with a typical spider-web appearance. B, The lesion was ablated with argon plasma coagulation.

C, Well-circumscribed ectasia in the midgastric body as seen on standard and (D) narrow band imaging.

Figure 3.91 VASCULAR ECTASIA ASSOCIATED WITH CIRRHOSIS

This ectasia has well-defined blood vessels emanating from the center of the lesion.

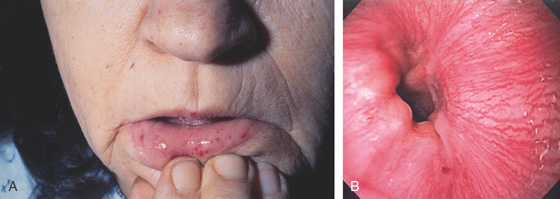

Figure 3.92 VASCULAR ECTASIAS OF OSLER-WEBER-RENDU SYNDROME

A, Multiple telangiectasias on the nose and lips. B, Pinpoint ectasia at the GE junction.

C, Large ectasia of the gastric body. D, Large ectasia in the duodenal bulb.

Figure 3.93 HEATER PROBE COAGULATION OF BLEEDING VASCULAR ECTASIAS

A, Active bleeding from the gastric body. B, With washing, bleeding is seen to emanate from a pinpoint area consistent with a vascular ectasia. C, The thermal probe is applied to the lesion, resulting in a white eschar and hemostasis. D, Follow-up endoscopy 3 days later shows the ectasia is ablated and a small ulcer has been iatrogenically created.

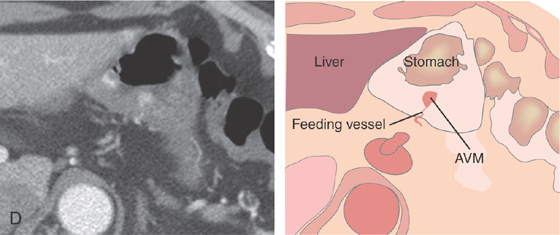

Figure 3.94 ARTERIAL VENOUS MALFORMATION

A1, Large, raised structure with central area of apparent fresh bleeding in the midgastric body. After washing, the raised lesion has a typical vascular ectasia appearance on its surface with an ulcer (A2). A3, The lesion is also well shown on retroflexion. B, Several other ectasias are also shown in the duodenum. C1, C2, The ERBE laser is used to ablate the lesion, resulting in eschar.

D, Computed tomography scanning with contrast shows a large arterial venous (AV) malformation (AVM) in the body of the stomach.

Figure 3.95 GASTRIC ANTRAL VASCULAR ECTASIA (GAVE) SYNDROME ASSOCIATED WITH PORTAL HYPERTENSION

A, Multiple ectasias in the antrum in a patient with small esophageal varices (B). C, Multiple similar-appearing lesions were present in the second duodenum. D, Cluster of ectasias surrounds the pylorus, and scattered lesions are seen in the antrum. This patient had small esophageal varices.

Figure 3.96 GASTRIC ANTRAL VASCULAR ECTASIA (GAVE) SYNDROME (WATERMELON STOMACH)

A, Multiple red stripes with a nodular appearance emanate from the antrum.

B, Multiple dilated capillaries in the submucosa and epithelium. C, Fibroproliferation, highlighted by trichrome stain, is characteristic of GAVE.

Figure 3.97 GASTRIC ANTRAL VASCULAR ECTASIA (GAVE) SYNDROME (WATERMELON STOMACH)

A, Multiple red hemorrhagic stripes emanating from the pylorus.

B, Dilated capillaries (arrow) and a fibrin thrombus are present.

Figure 3.98 GASTRIC ANTRAL VASCULAR ECTASIA (GAVE) SYNDROME (WATERMELON STOMACH)

A, Red stripes emanating from the pylorus. Some have a nodular appearance, whereas others are flat. A2, A3, The vascular nature of the lesion is highlighted by narrow band imaging.

B, Appearance immediately after thermal ablation with argon plasma coagulation. C, Two-month follow-up shows improvement of lesions, with whitish areas representing scarring. D, Petechial lesions in the cardia are common in patients with GAVE.

E, Cardia lesions immediately after thermal ablation.

Figure 3.99 GASTRIC ANTRAL VASCULAR ECTASIA (GAVE) SYNDROME (WATERMELON STOMACH)

A, More diffuse involvement of the antrum; although more proximally, the lesions do retain a watermelon appearance. Such an appearance is often attributed inappropriately to gastritis. B, Laser ablation performed. C, Partial ablation.

D1, D2, Complete ablation of the antrum.

Figure 3.100 RADIATION-INDUCED VASCULAR ECTASIAS

A, Multiple ectasias in the proximal stomach. This patient had radiation therapy after resection for gastric adenocarcinoma of the cardia. B, Marked edema with diffuse vascular ectasias of the gastric antrum after radiation therapy for pancreatic cancer. C, Multiple delicate blood vessels posteriorly in the antrum.

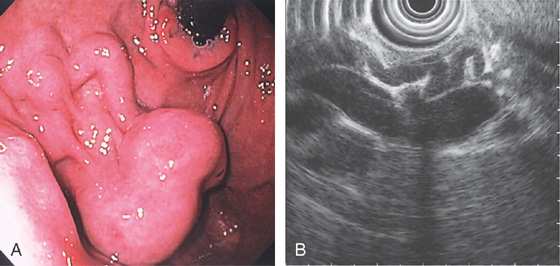

Figure 3.101 GASTRIC VARICES

A, Irregularly shaped, masslike lesion in the gastric fundus.

B, C, Retroflex view of the fundus demonstrates dilated veins with a “sack of grapes,” representing a cluster of gastric varices.

Figure 3.102 GASTRIC VARIX

A, Large gastric varix with mucosal defect representing recent bleeding. B, Close-up of the mucosal defect shows ulceration with a visible vessel. C, Variceal sclerotherapy was performed for spontaneous bleeding.

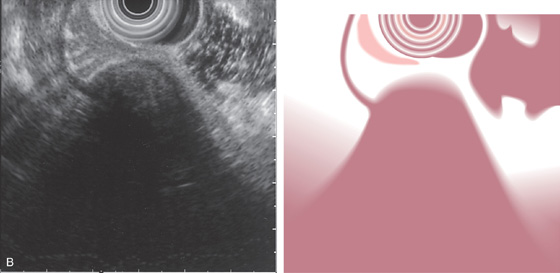

Figure 3.103 GASTRIC VARIX

A, Typical-appearing cluster of fundal varices. B, Endoscopic ultrasonography shows the small varices feeding into the larger varix.

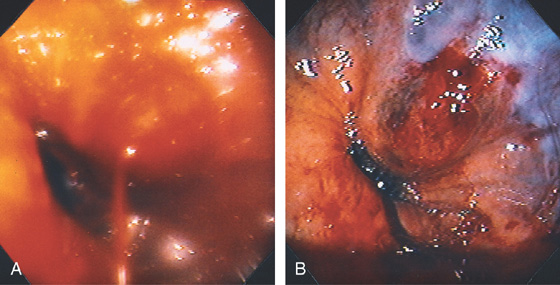

Figure 3.104 BLEEDING GASTRIC VARIX

A, Bleeding varix just distal to the gastroesophageal junction. B, After injection sclerotherapy and cessation of bleeding, the varix has a dark discoloration. The bleeding point is clearly below the gastroesophageal junction.

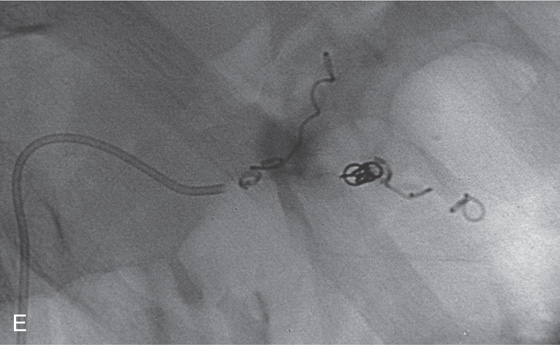

Figure 3.105 PRIOR GASTRIC VARICEAL EMBOLIZATION

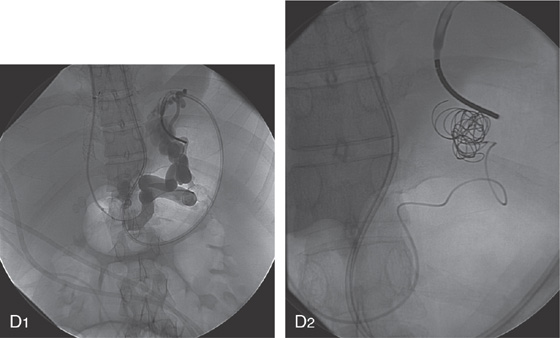

A, B, The coil material is now emanating from the prior gastric ulcer in the proximal stomach. C, Forceps are used to grasp the material, but it could not be removed.

D1, Appearance of the embolized vessel at the time of the initial procedure 2 years earlier. Note the presence of large gastric varices and a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Multiple coils were placed (D2).

Figure 3.106 GASTRIC VARICES AND SPLENIC VEIN THROMBOSIS

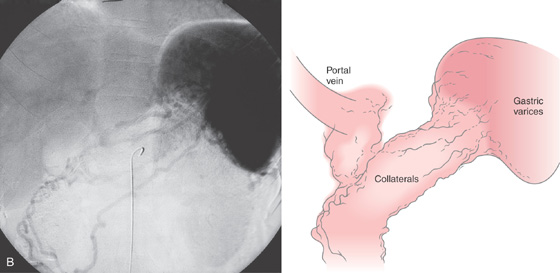

A, The distal esophagus is normal (A1). The rugae of the gastric body are prominent, as a result of dilated veins (A2). The gastric antrum is normal (A3). Retroflex view of the fundus demonstrates clusters of dilated veins (A4).

B, Drawing of the venous phase of the abdominal angiogram shows dilated veins (varices), as well as collaterals in the proximal stomach. Portal vein flow is barely visible, given the collateral flow. The splenic vein is not seen.

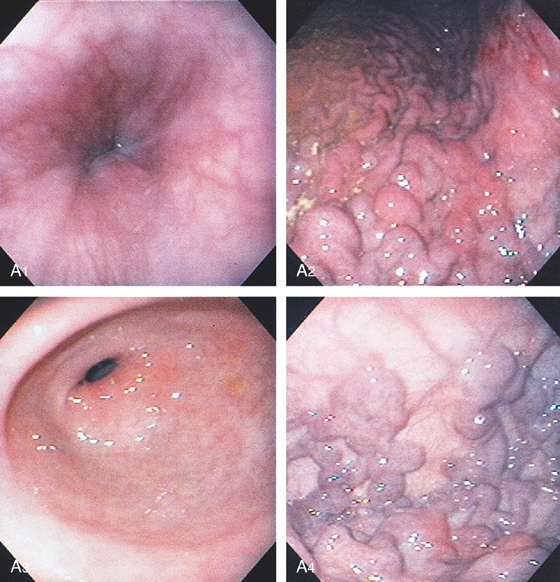

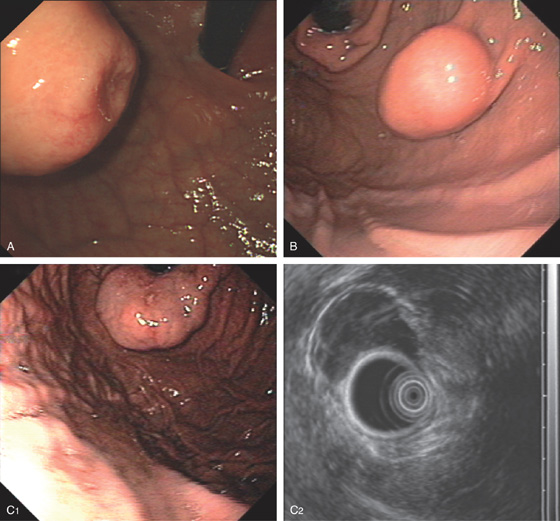

Figure 3.107 FUNDIC GLAND POLYP

A, Small polyp in the proximal stomach. B, Multiple irregular glands with dilated lumen, forming cystic structures.

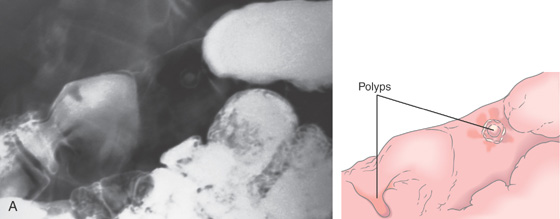

Figure 3.108 FUNDIC GLAND POLYPS IN FAMILIAL ADENOMATOUS POLYPOSIS SYNDROME

A, Multiple polyps produce filling defects.

B, Multiple small polyps of similar appearance studding the proximal stomach. C, Close-up shows the appearance of the polyps.

D, Multiple well-circumscribed polyps typical for fundic gland lesions. Note the smooth appearance and subtle vascular pattern (E).

Figure 3.109 FUNDIC GLAND POLYPS

A, Multiple polyps in the gastric body. B, Close-up of the polyps demonstrates a “fleshy” appearance. C, More numerous polyps with similar appearance. D, Solitary polyp of modest size with subtle vascular pattern and smooth rather than fleshy overlying mucosa.

E, Complete resection shows the characteristic findings with the numerous areas of cystic dilation.

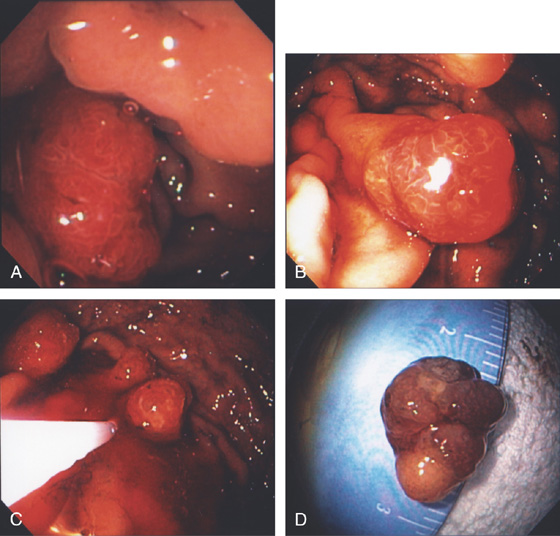

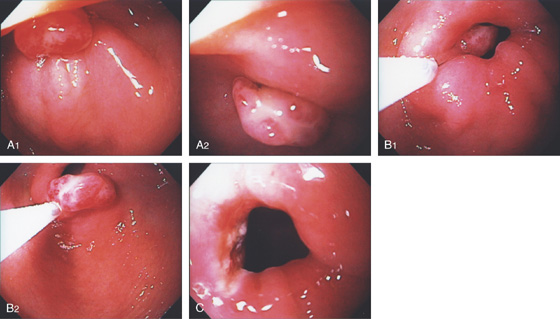

Figure 3.110 HYPERPLASTIC POLYPS

Multiple small polyps of the gastric antrum. Note that a number of the lesions have overlying exudate.

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Hyperplastic Polyp (Figure 3.110)

Inflammatory polyp

Fundic gland polyp

Adenomatous polyp

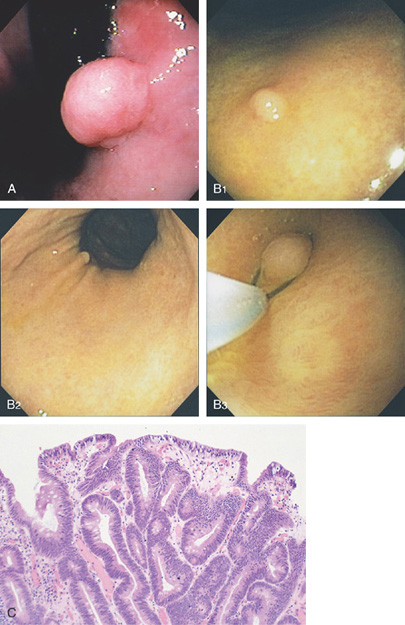

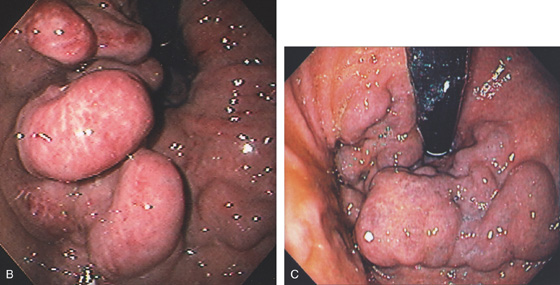

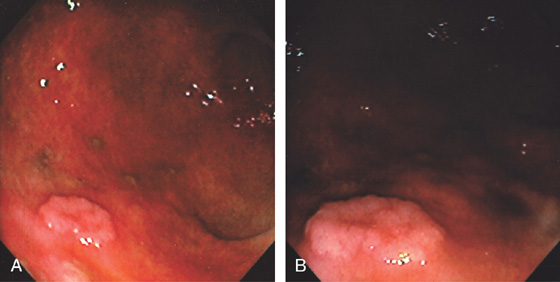

Figure 3.111 MULTIPLE LARGE HYPERPLASTIC POLYPS

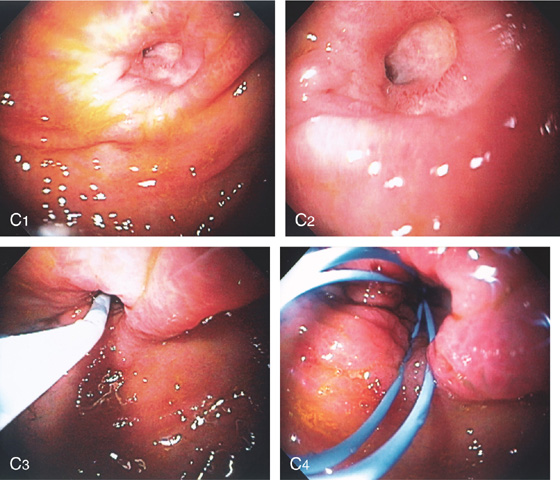

A, B, Multiple large red polyps in the gastric antrum. C, The polyp is snared at the base and resected using standard techniques. D, The size of the polyp is noted.

E-G, Cystically dilated gastric foveolar glands with varying amounts of inflammation and overlying ulceration. Intervening lamina propria shows marked edema.

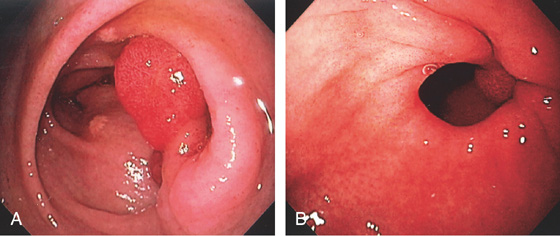

Figure 3.112 HYPERPLASTIC POLYP

A, Solitary pedunculated polyp in the peripyloric area. B, The polyp was seen to prolapse in and out of the pylorus.

C1, C2, Marked foveolar hyperplasia and edema.

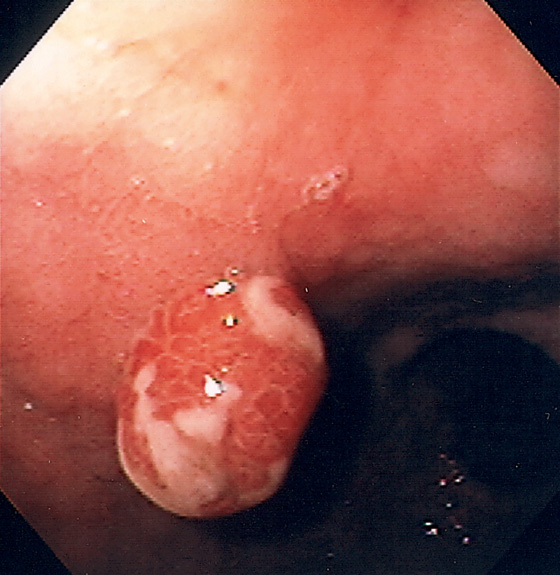

Figure 3.113 HYPERPLASTIC POLYP

Solitary polyp in the distal gastric body anteriorly. Note the reddish discoloration of the polyp with overlying exudate typical for hyperplastic polyps.

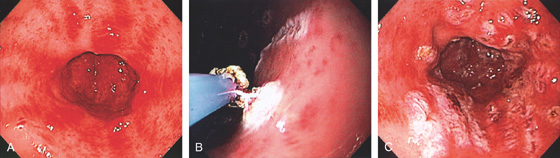

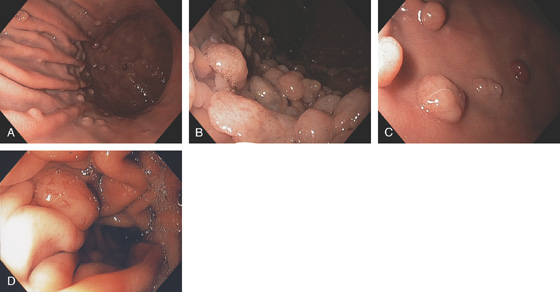

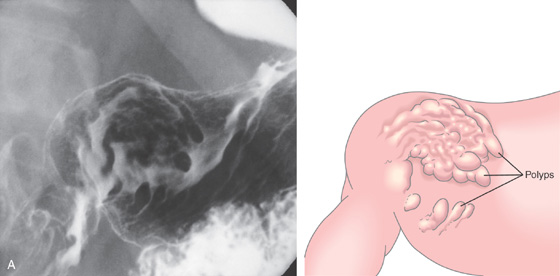

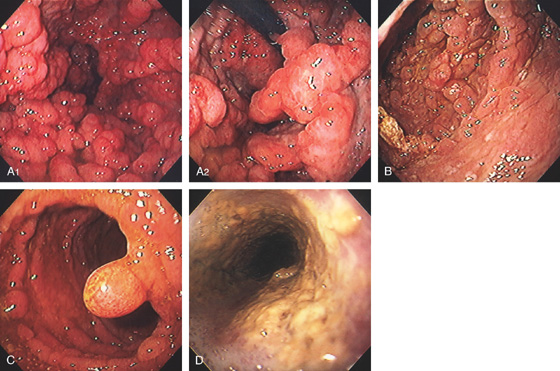

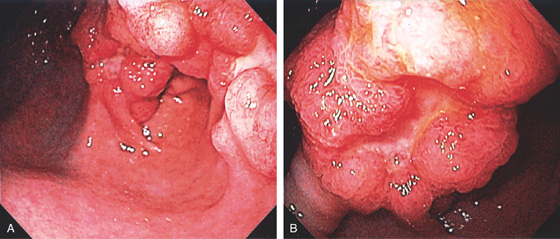

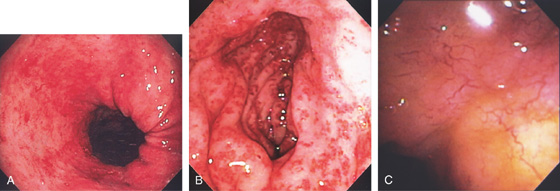

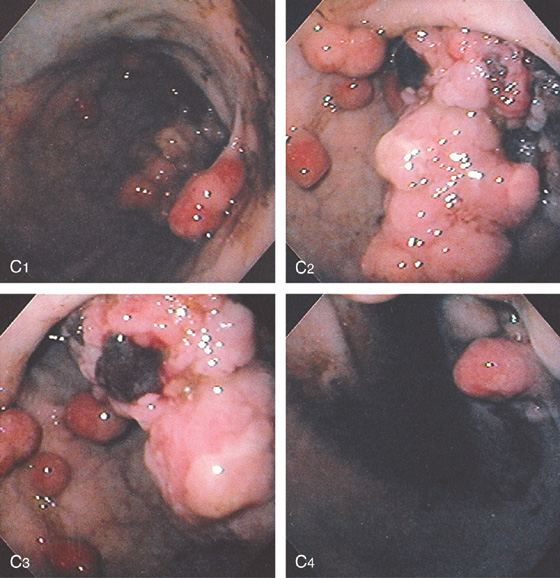

Figure 3.114 INFLAMMATORY POLYPS

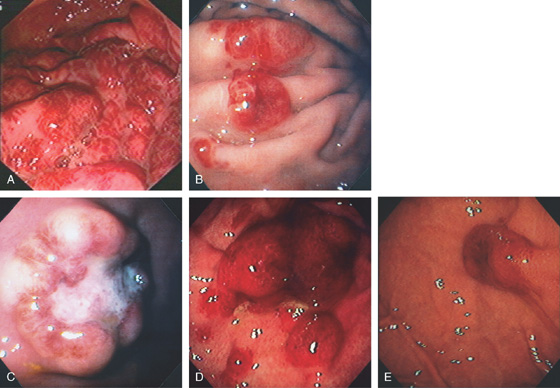

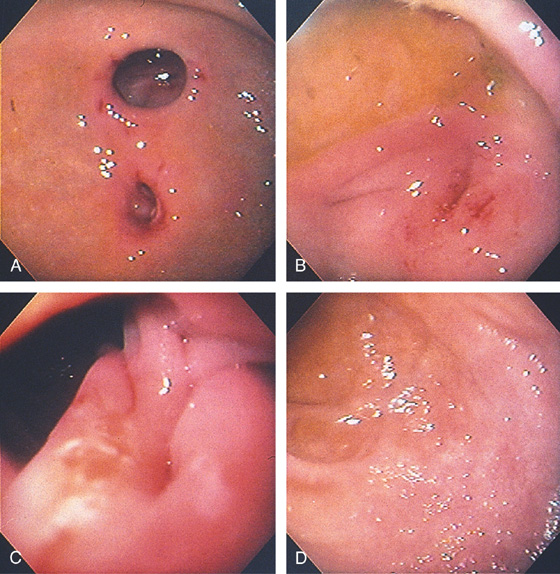

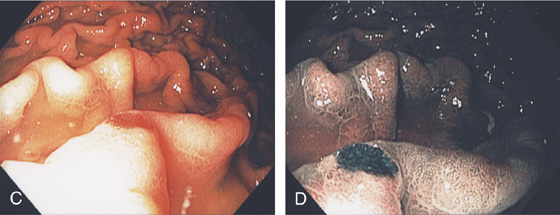

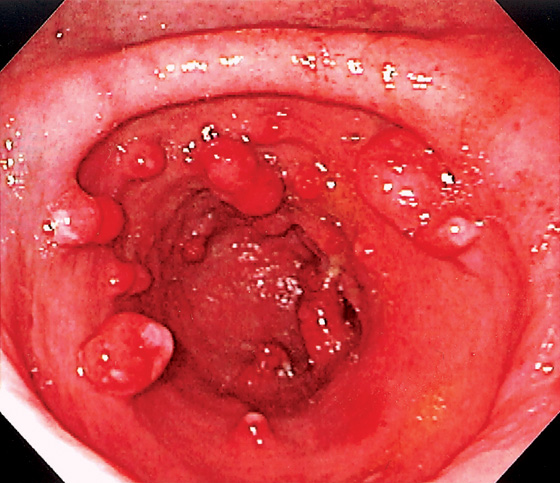

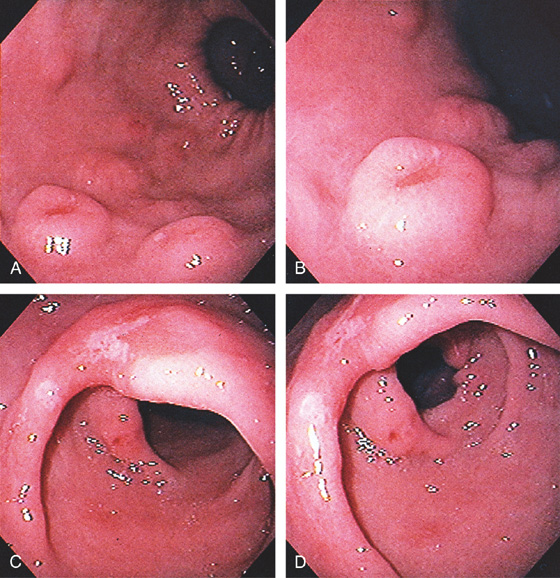

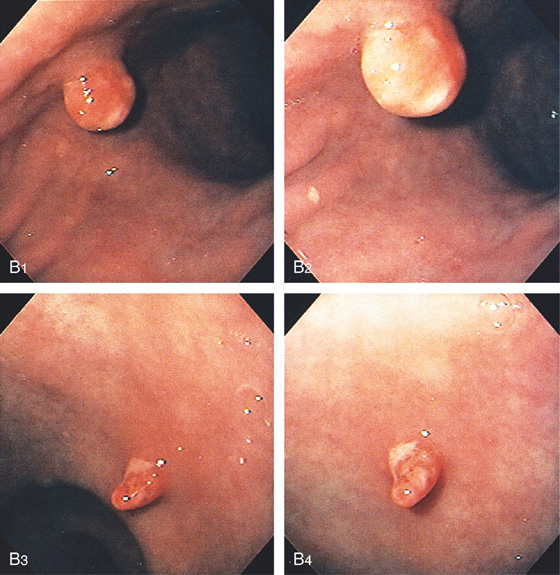

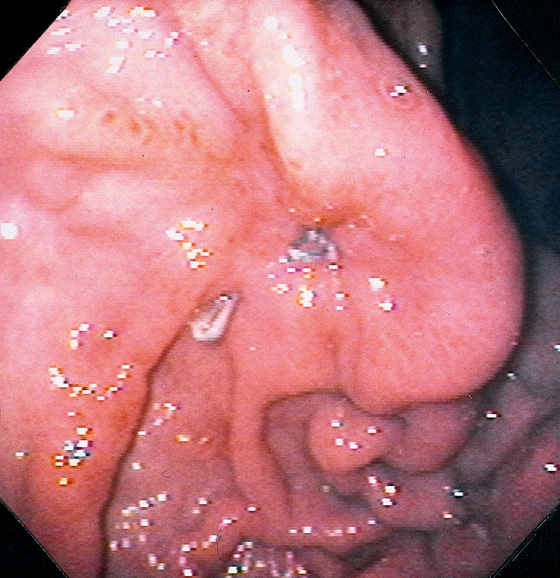

Multiple nodular lesions with a central depression, resembling a volcano, in the gastric body (A, B). The gastric antrum is noted to be inflamed, with areas of erosion (C, D).

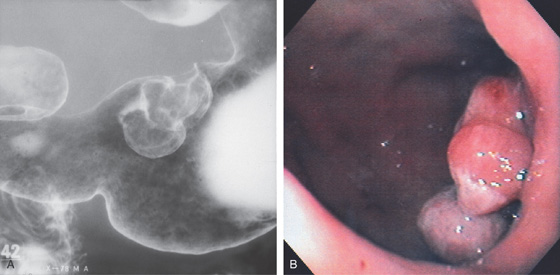

Figure 3.115 INFLAMMATORY POLYPS

A, Nodular defects of varying size and shape in the gastric antrum. A small fleck of barium is in the center of some of the lesions.

B, Small round defects with a central depression in a linear pattern (left).

Figure 3.116 INFLAMMATORY POLYP

Single filiform lesion in the distal gastric body.

Figure 3.117 INFLAMMATORY POLYPS

A, Two defects in the gastric body and antrum: on the right, a round “bowler hat” lesion; on the left, a nipple-like lesion projecting into the lumen and surrounded by barium.

B, The “bowler hat” lesion is seen to be a round polyp with overlying erosion (B1, B2). The distal lesion is a finger-like projection of inflammatory tissue, also with an erosion (B3, B4).

Figure 3.118 INFLAMMATORY POLYP

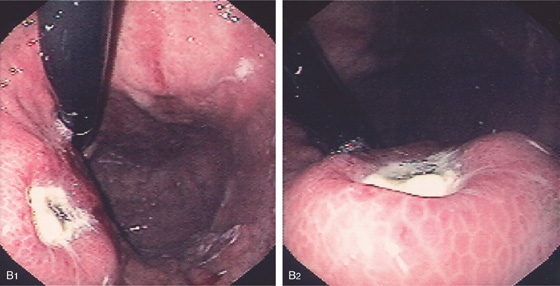

A1, A2, Round polypoid lesion with overlying ulceration at the pylorus. B1, B2, The polyp was snared and removed, leaving an eschar in the pyloric canal (C).

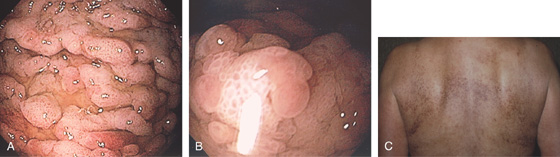

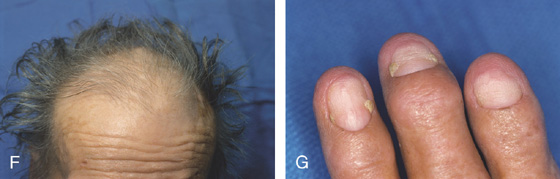

Figure 3.119 CRONKHITE-CANADA SYNDROME

This syndrome is characterized by the tetrad of cutaneous hyperpigmentation, alopecia, onychodystrophy, and intestinal polyps. A1, A2, Multiple polyps throughout the stomach, duodenum (B), and ileum (C). D, Candida esophagitis accompanies the syndrome.

E, Hyperpigmentation of the torso with an area of vitiligo.

F, Alopecia. G, Onycholysis of the nails.

H, A neck brace is worn because of onychodystrophy.

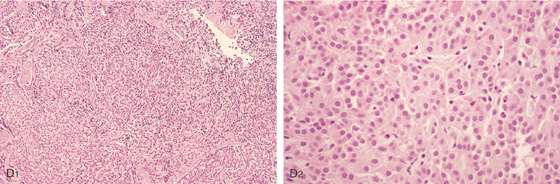

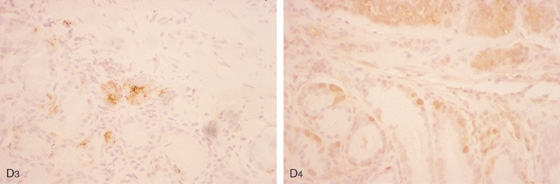

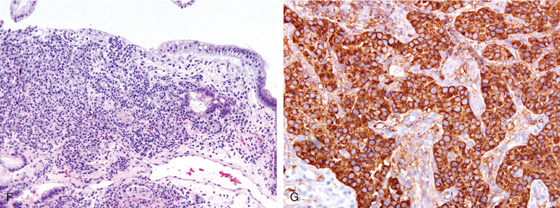

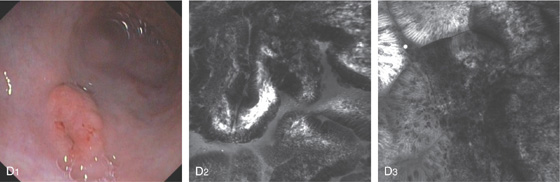

Figure 3.120 GASTRIC CARCINOID TUMOR

A, Solitary polyp with central erosion in the proximal stomach as shown on retroflexion. Note the marked gastric atrophy. B, Multiple small polyps throughout the gastric body, many with overlying exudate. C, Small lesion with erosion in a patient with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome and multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 1.

D1, D2, Small cells that form nests typical for carcinoid tumors.

D3, Both chromogranin and neuron-specific enolase (NSE) (D4) often show positive staining in carcinoid tumors.

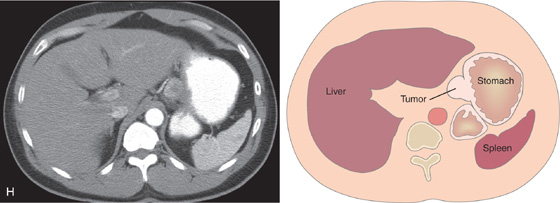

Figure 3.121 GASTRIC CARCINOID TUMOR

A1, Well-circumscribed donut-shaped lesion in the midgastric body posteriorly. Fresh heme is on the lesion. A2, The size of the lesion is measured using open biopsy forceps. Note the absence of gastric atrophy. The lesion is also well shown on retroflex view (B). C, The appearance of the lesion on narrow band imaging. The lesion is tattooed with India ink (D, E).

F, Nests of small cells infiltrate the gastric mucosa typical for carcinoid tumor. G, Positive chromogranin staining of the tumor confirms the neuroendocrine origin.

H, Well-circumscribed, hyperenhancing lesion in the gastric body corresponding with the tumor.

Gastric Carcinoid Tumor (Figure 3.121)

Metastatic lesion

Melanoma

Breast

Lung

Primary gastric lymphoma

Figure 3.122 GARDNER’S SYNDROME

Multiple gastric polyps throughout the gastric body (A) and fundus (B). Histologically, these polyps are fundic gland polyps. C, Note on close-up the fleshy appearance of the polyps typical for fundic gland polyps. (See Figure 3.109.)

Figure 3.123 COWDEN SYNDROME

Multiple small, benign-appearing gastric polyps. In Cowden syndrome, these polyps are histologically hamartomas.

Figure 3.124 PEUTZ–JEGHERS SYNDROME

Multiple small gastric polyps throughout the gastric body. Histologically, these polyps are hamartomas.

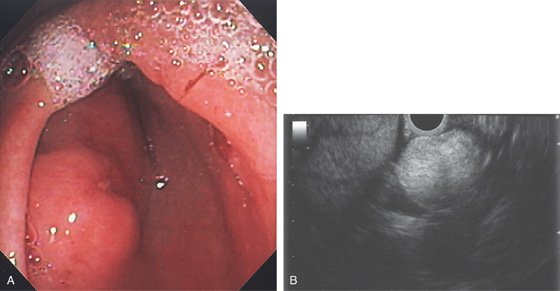

Figure 3.125 LEIOMYOMA

A, Large submucosal mass lesion in the gastric body.

B, Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) shows the lesion arises from the muscularis propria, confirming a leiomyoma.

Figure 3.126 LIPOMA

A, Submucosal lesion with central erosion in the proximal antrum. B, EUS shows a well-circumscribed lesion that is hyperechoic.

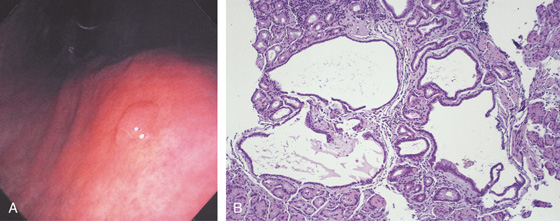

Figure 3.127 TUBULAR ADENOMA

A, Large polyp just proximal to the angularis shown on retroflexion. The polyp has a serpentine appearance, typical of an adenoma. B1, Well-circumscribed small polyp of the distal gastric body in the setting of gastric atrophy and pernicious anemia, which was resected (B2). C, Polypectomy specimen shows typical adenomatous glands.

Figure 3.128 TUBULAR ADENOMA

A, Small polyp of the distal gastric body. B, Note the whitish discoloration of the lesion, representing intestinal metaplasia, and the surrounding gastric atrophy.

Figure 3.129 TUBULAR ADENOMA WITH CARCINOMA

A, Large polypoid lesion of the gastric antrum. B, Note the central ulceration that suggests carcinoma.

Figure 3.130 ADENOMATOUS POLYPS AND CARCINOMA

A, Multiple round filling defects in the proximal gastric body and a large lesion at the angularis. B, A large, masslike lesion is present along the greater curvature and antrum.

Figure 3.130 ADENOMATOUS POLYPS AND CARCINOMA

C, Multiple round polypoid lesions seen in the proximal gastric body along the lesser curvature (C1, C4). Associated with the polyps is a large, masslike lesion in the distal body and antrum, representing cancer (C2, C3).

Figure 3.131 CARCINOMATOUS POLYP

A, Two polypoid defects originating from the lesser curvature in the distal gastric body. B, Trilobed polyp at the angularis.

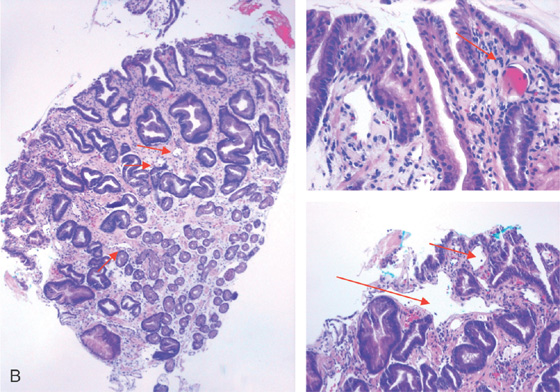

Figure 3.132 EARLY GASTRIC CANCER

Well-circumscribed, round, raised lesion of the distal gastric antrum.

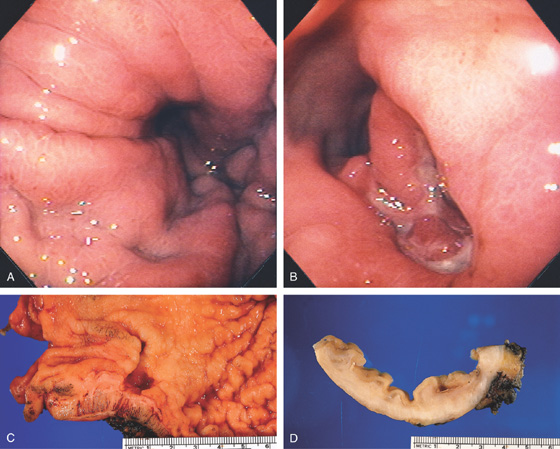

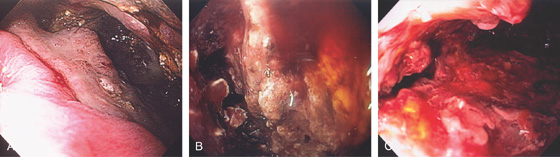

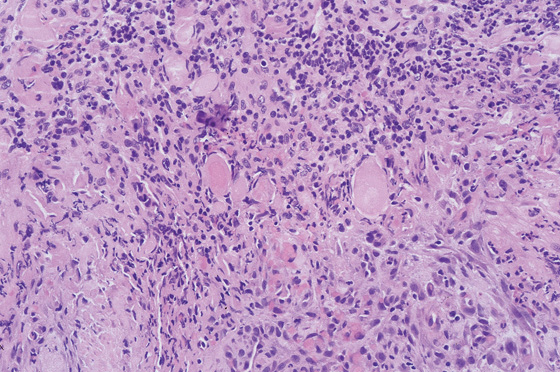

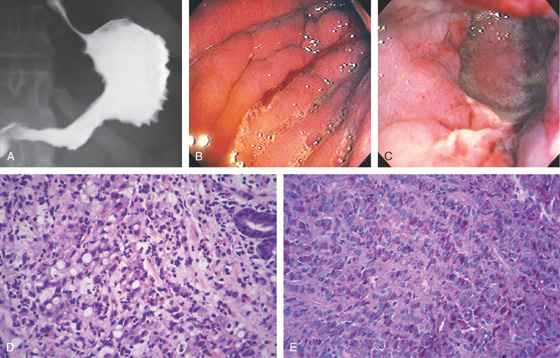

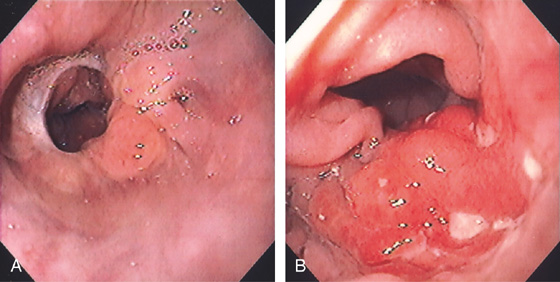

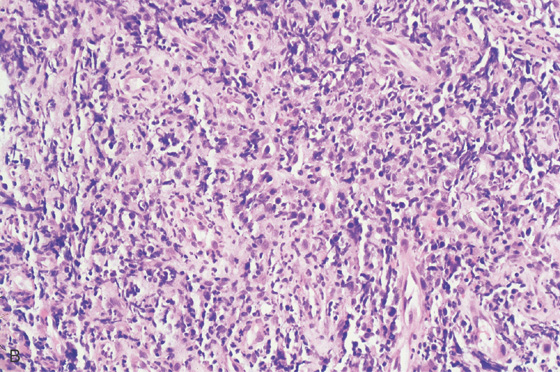

Figure 3.133 LINITIS PLASTICA

A, The gastric body and antrum are nondistensible and have a spiculated appearance, primarily along the greater curvature. B, The gastric rugae are thickened, and spontaneous bleeding is present in the distal body. Despite maximal insufflation, there was no further distention. C, Circumferential ulceration in the distal body and antrum. D, Poorly differentiated gastric carcinoma. Malignant signet ring cells are present, characterized by an intracytoplasmic mucin vacuole, which can compress the nucleus. E, Signet ring cells are demonstrated by histochemical stains for mucin, including mucicarmine and, in this figure, periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) reagent.

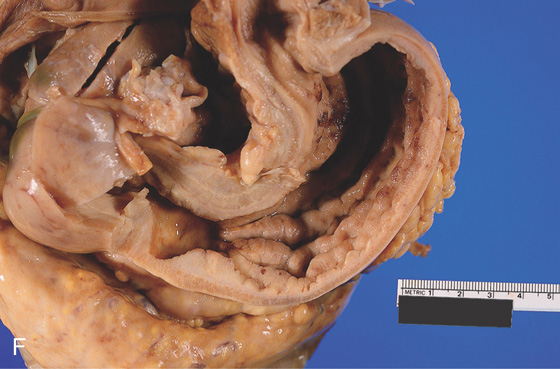

Figure 3.133 LINITIS PLASTICA

F, Postmortem specimen demonstrates the marked thickening of the entire stomach, as well as the thickened rugae.

Figure 3.134 LINITIS PLASTICA

A, The rugae are prominent, the mucosa is friable, and the stomach is poorly distensible. B, The gastric wall is diffusely thickened.

C, Oral contrast and air help to highlight the circumferential wall thickening (C1, C2).

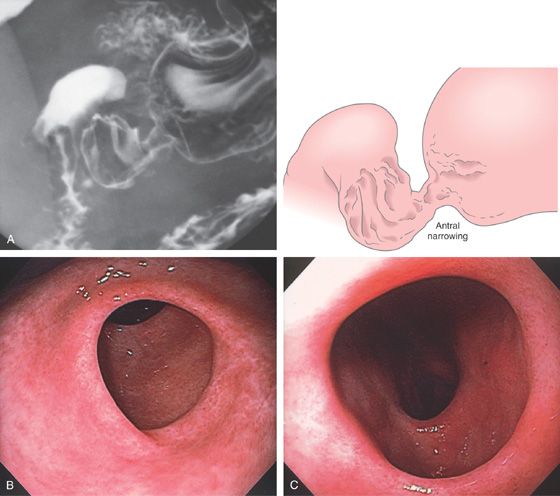

Figure 3.135 LINITIS PLASTICA SECONDARY TO METASTATIC BREAST CANCER

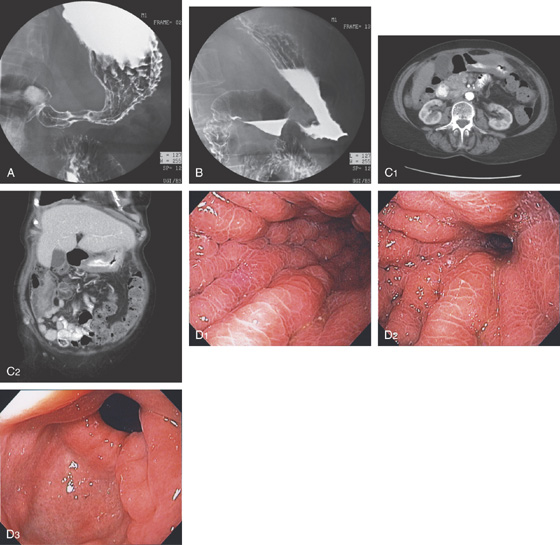

A, B, Upper gastrointestinal (GI) series shows thickened folds with narrowing of the antrum. C1, C2, Marked thickening of the gastric wall as shown on routine and coronal CT images. D1, D2, Gastric folds are markedly thickened and the gastric lumen is narrowed. The antrum is relatively spared (D3).

Figure 3.135 LINITIS PLASTICA SECONDARY TO METASTATIC BREAST CANCER

E1, E2, Numerous malignant cells fill the submucosa. The cells are estrogen receptor positive on special staining, confirming metastatic breast cancer (F1, F2).

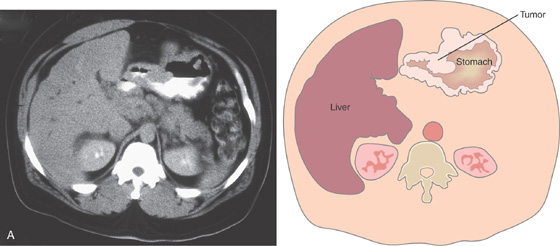

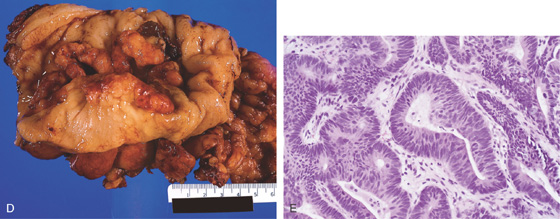

Figure 3.136 ADENOCARCINOMA

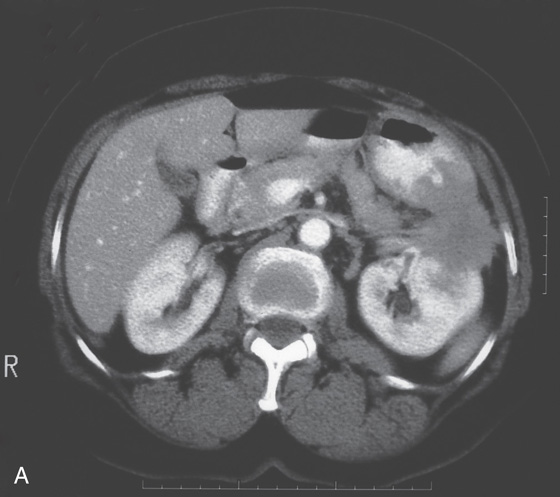

A, Marked thickening of the gastric body and antrum.

B, Ulcerated mass originating in the gastric body. The surrounding mucosa does not appear to be involved. C, The ulcerated neoplasm extends toward the pylorus, with the lesser curvature uninvolved.

D, The stomach has been everted, showing the tumor. E, Well-differentiated adenocarcinoma.

Figure 3.137 ADENOCARCINOMA

A, The gastric body appears to be fixed toward the antrum. The areae gastricae are prominent. B, An irregularly shaped ulceration in the center of the antrum. The gastric body is fixed toward this lesion. The antrum, in the distance, appears normal. C, The thickened rugae and irregular shape of the ulcer are apparent. D, The gastric wall and rugal folds are markedly thickened at the level of the ulceration.

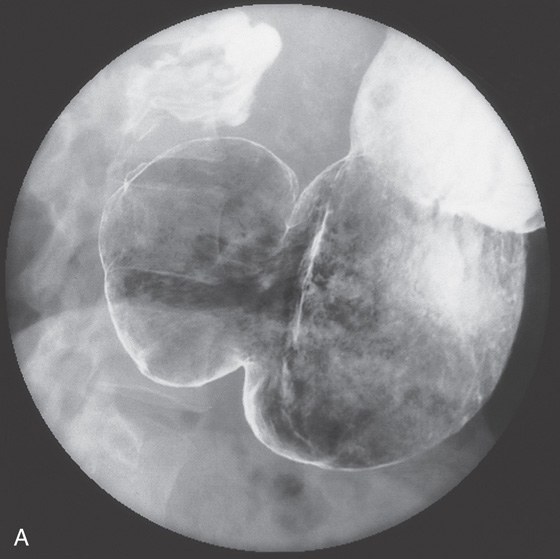

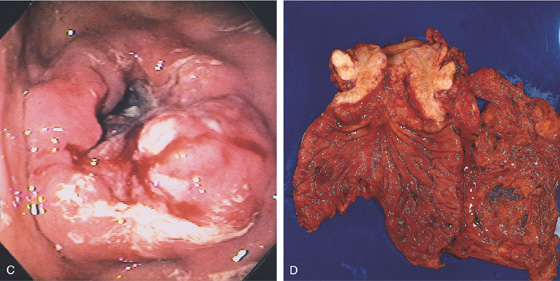

Figure 3.138 ADENOCARCINOMA

A, Markedly dilated stomach with an abrupt cutoff in the antrum. B, Markedly dilated stomach is outlined by barium. An apple-core-like lesion can be seen in the antrum.

C, Circumferential masslike lesion involving the gastric body and collapsing the antrum. D, An annular constricting neoplasm with a fibrotic appearance is demonstrated on this surgical specimen.

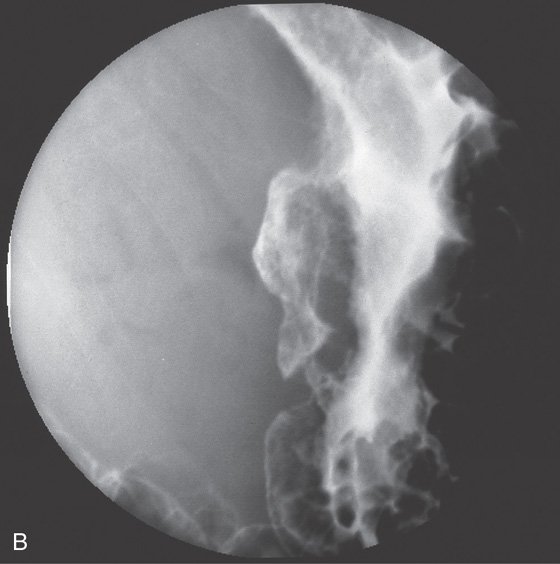

Figure 3.139 ADENOCARCINOMA

A, Irregularly shaped ulceration on the angularis. There is associated thickening of the gastric rugae, some of which are not smooth in appearance.

B, Close-up view of the ulcer demonstrates the irregular appearance of the ulcer mound, especially along the distal margin, with associated thick gastric folds surrounding the crater. The nodular appearance of both the distal ulcer mound and the folds suggests malignancy.

Figure 3.139 ADENOCARCINOMA

C, Marked thickening and erythema of the gastric rugae (C1). A large gastric ulcer with heaped-up margins extends from the midbody to the angularis (C2, C3). Retroflex view demonstrates the irregularity of the surrounding margin in relation to the ulcer base (C4).

D, The malignant ulcer is deep, and the prominent rugal folds are identified in the surgical specimen.

Figure 3.140 ADENOCARCINOMA

Round, masslike lesion of the gastric body.

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Adenocarcinoma (Figure 3.140)

Neuroendocrine neoplasm

Metastatic tumor

Melanoma

Breast cancer

Lung cancer

Other

Primary gastric lymphoma

Figure 3.141 GASTRIC ADENOCARCINOMA

A, Well-circumscribed lesion in the posterior gastric body.

B, Typical adenocarcinoma with signet ring cells shown on close-up. Mucicarmine stain also highlights the type of tumor (C).

D1, Elevated polypoid lesion in the proximal antrum. D2, Endomicroscopic image with optical coherence tomography shows abnormal glands with clusters of dark neoplastic cells. D3, Intestinal metaplasia is in the mucosa surrounding the tumor. (B courtesy J. Pardo-Mindan, MD, Pamplona, Spain.)

Figure 3.142 GASTRIC ADENOCARCINOMA AFTER BILLROTH-II ANASTOMOSIS (STUMP CARCINOMA)

A, Ulcerated mass lesion at the anastomosis. B, Retroflexion shows the extent of proximal progression.

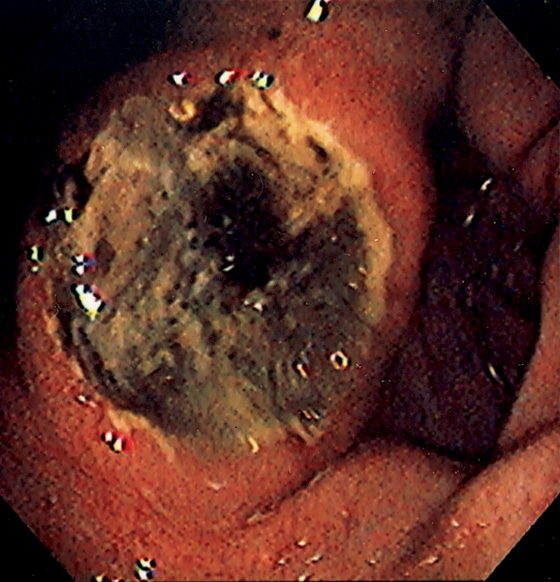

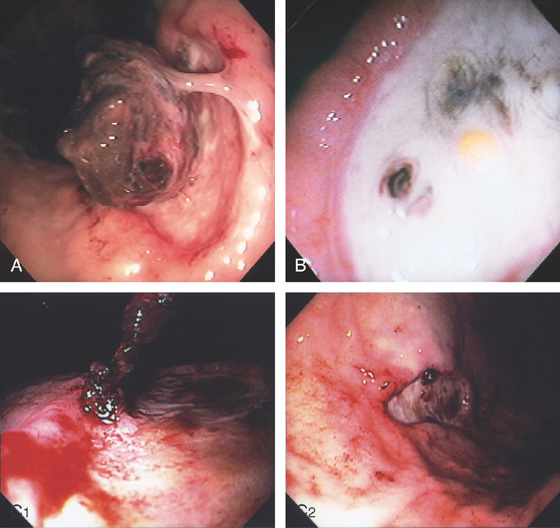

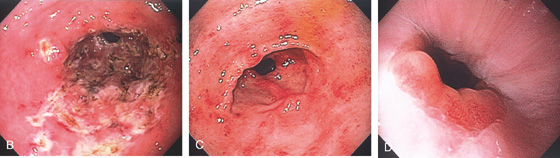

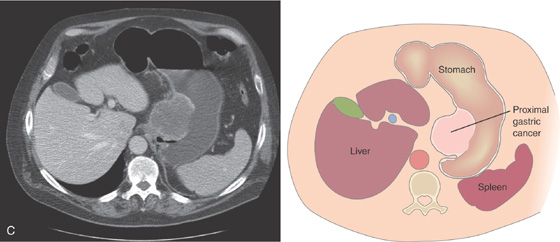

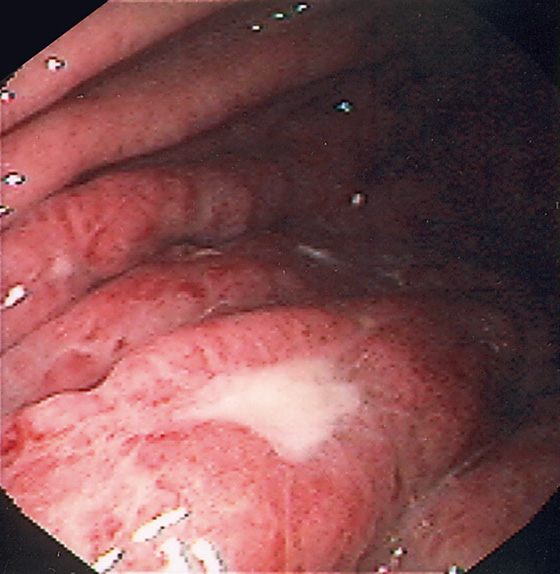

Figure 3.143 MALIGNANT GASTRIC ULCER

This gastric ulcer is linear but irregular and has heaped-up lips to the margin. The lips do not form a circumferential pattern around the ulcer base.

Figure 3.144 MALIGNANT GASTRIC ULCER

Large, deep ulcer on the lesser curvature.

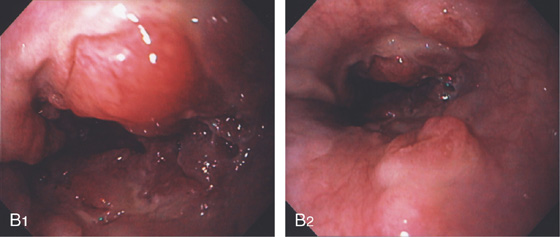

Figure 3.145 PROXIMAL GASTRIC CANCER

A1-A3, Large ulcerated lesion in the gastric cardia with thick exudate.

Note the extension to the gastroesophageal junction (B1) and distal upper with multiple submucosal nodular lesions (B2).

C, Large mass lesion in the proximal stomach posteriorly.

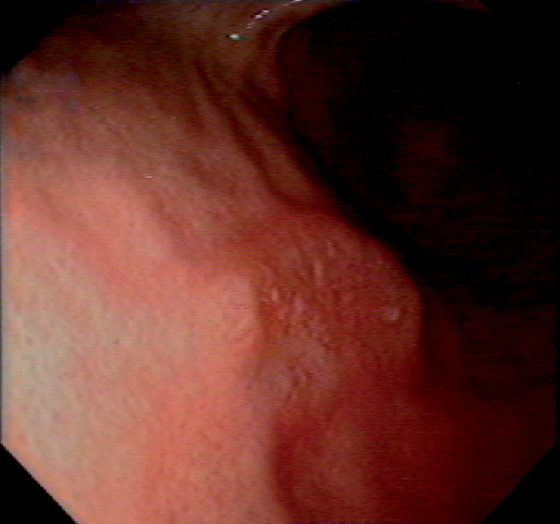

Figure 3.146 EARLY GASTRIC CANCER

Multiple white verrucous-appearing plaques along the greater curvature in the antrum.

Figure 3.147 RECURRENT GASTRIC CANCER

A, Normal-appearing esophagogastric anastomosis after proximal gastric resection. B, Masslike lesion just distal to the anastomosis.

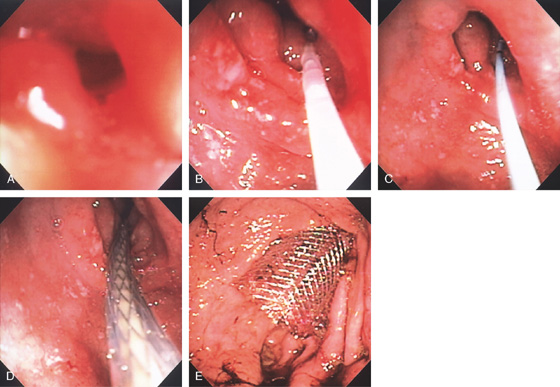

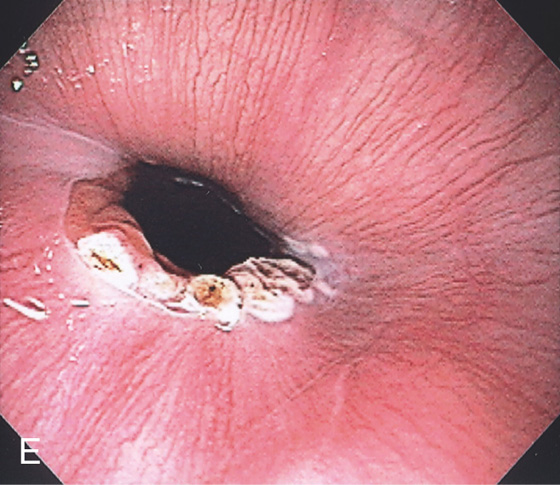

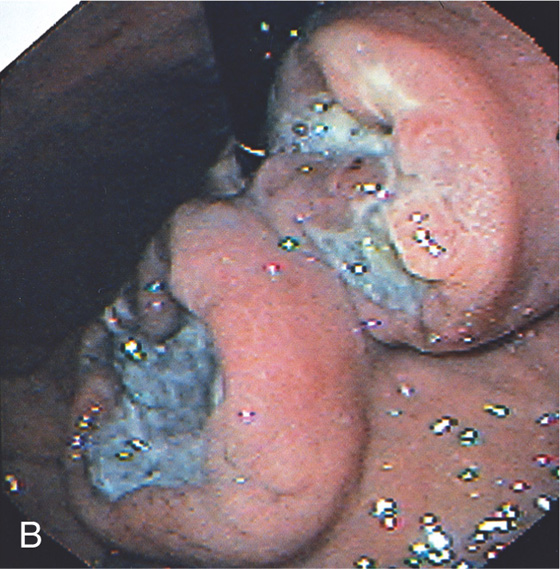

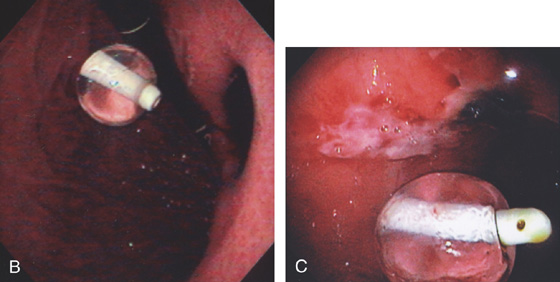

Figure 3.148 ENTERAL STENT PLACEMENT FOR OBSTRUCTING ADENOCARCINOMA OF THE ANTRUM

A, Endoscopic view shows a pinpoint opening in the antrum. B, A floppy guidewire was passed through the lesion under fluoroscopic guidance and exchanged for a stiffer wire. C, The catheter is seen for the wire exchange. D, Over this wire, the metal prosthesis is advanced. E, The stent has been fully deployed.

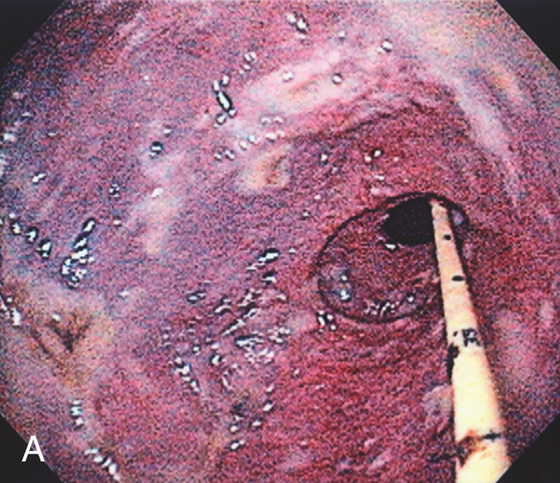

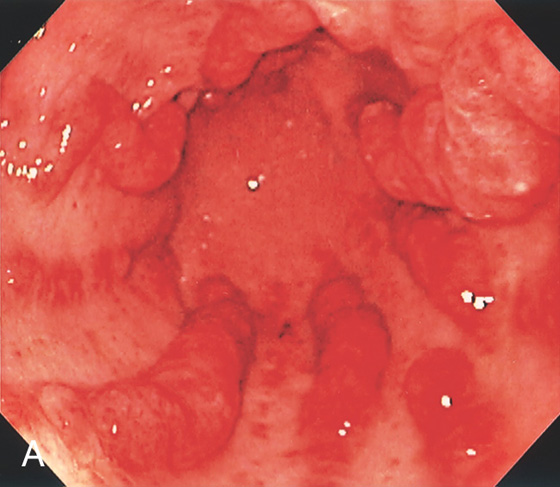

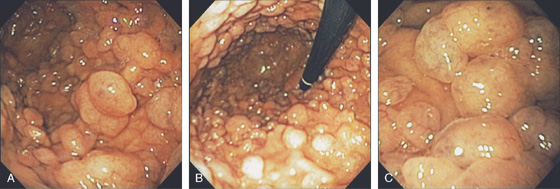

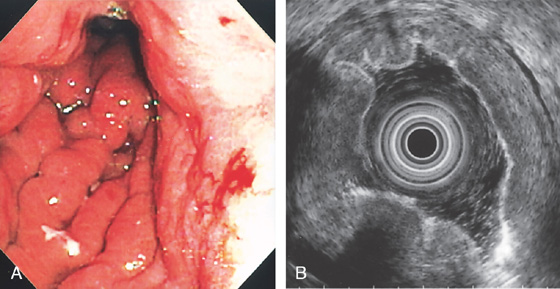

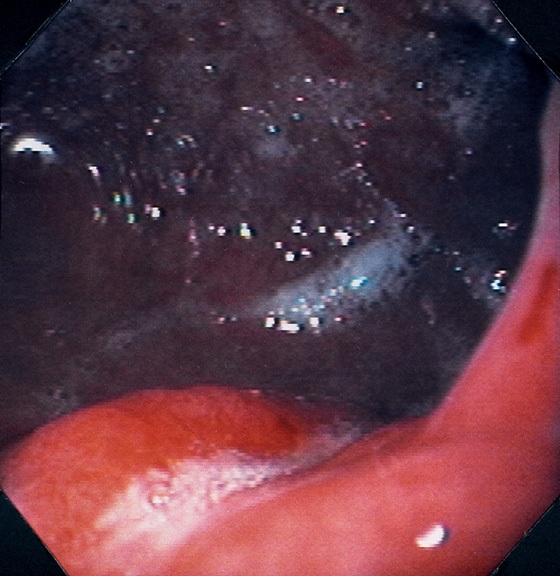

Figure 3.149 GASTRIC LYMPHOMA

A, Multiple umbilicated lesions distal to the gastroesophageal junction. One large ulceration is just distal to the squamocolumnar junction.

B, Atypical lymphoid infiltrate with large immunoblastic-type cells.

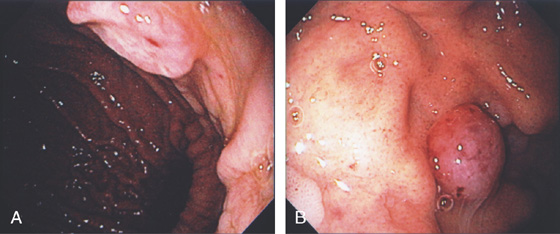

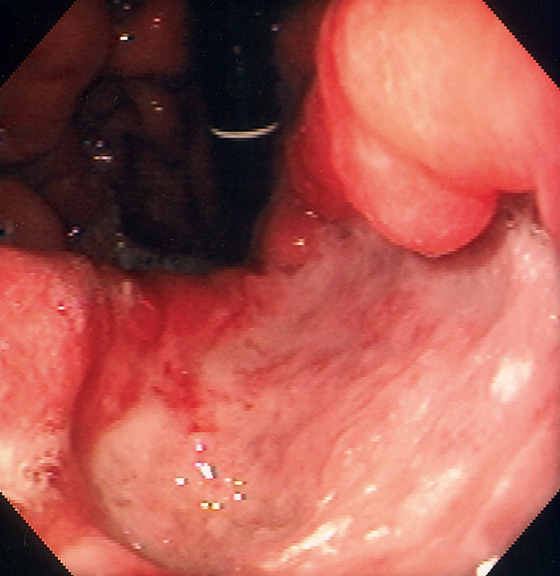

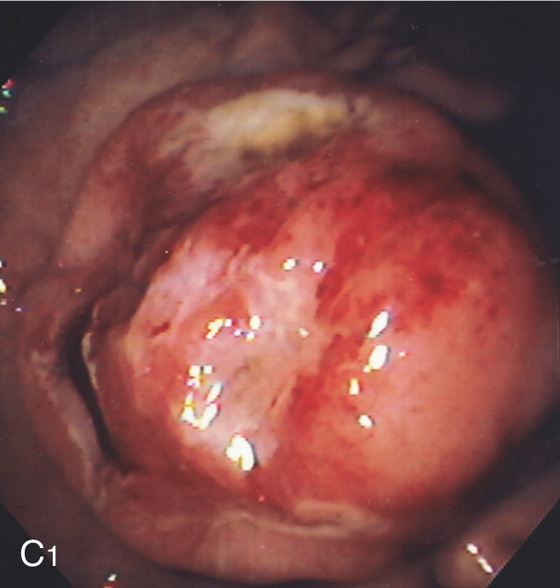

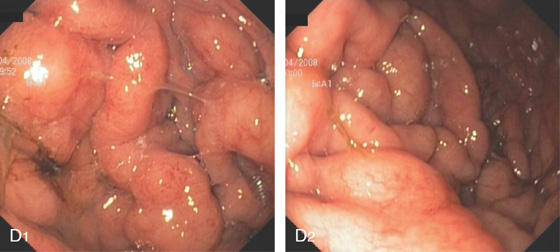

Figure 3.150 GASTRIC LYMPHOMA

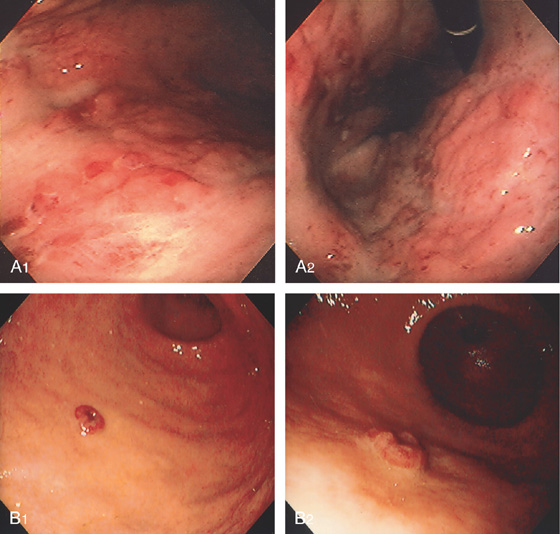

A1, A2, Diffuse erythema, hemorrhage, and nodularity of the gastric body. B1, Small reddish raised lesion of the distal gastric body. B2, Close-up shows a central defect.

C1, Large, well-circumscribed, ulcerated, masslike lesion in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). The lesion was soft on biopsy.

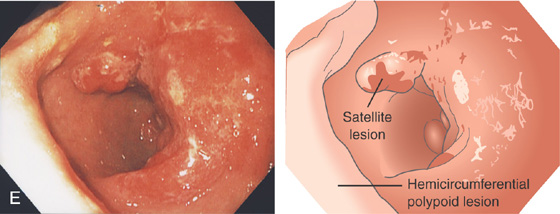

C2, Atypical lymphoid infiltrate with large immunoblastic-type cells. D, Ulcer with raised margin extending distally in a serpiginous fashion.

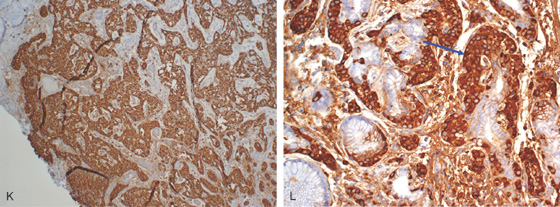

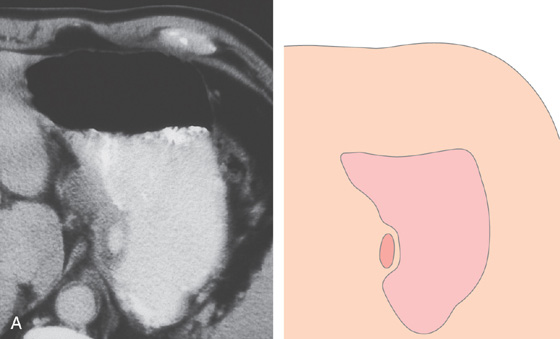

E, Hemicircumferential polypoid lesion with overlying exudate occupying the gastric antrum posteriorly. Note the satellite lesion anteriorly by the pylorus (drawing).

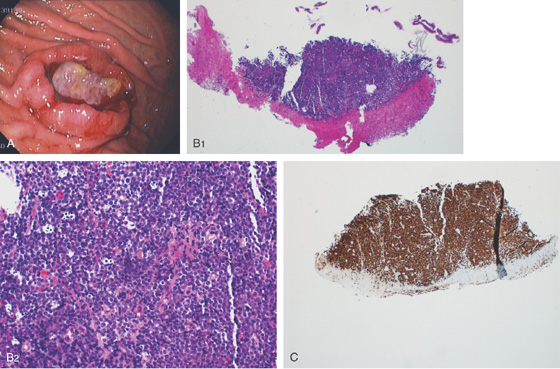

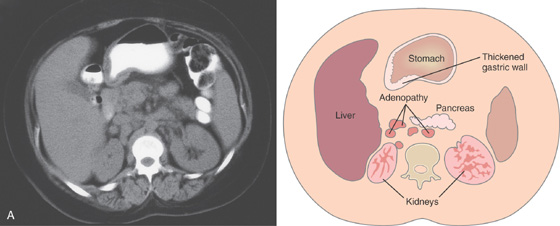

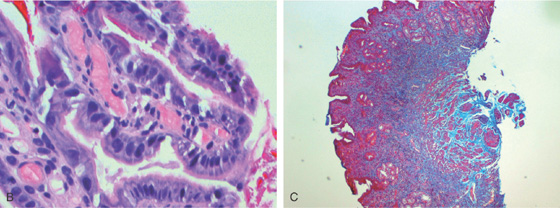

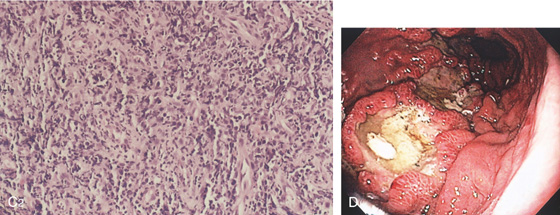

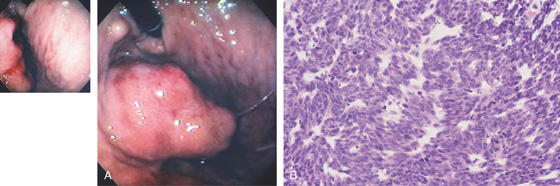

Figure 3.151 B CELL GASTRIC LYMPHOMA

A, Well-circumscribed donut lesion with central ulceration and fresh bleeding in the gastric body anteriorly. B1, B2, Ulcerated gastric mucosa with malignant lymphomatous infiltrate (diffuse large B cell lymphoma). C, Special stain for MUM1 demonstrated activated B lymphocytes, confirming the diagnosis and type of lymphoma.

D1, D2, This B cell lymphoma resulted in diffuse thickening of the gastric folds.

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

B Cell Gastric Lymphoma (Figure 3.151)

Gastric adenocarcinoma

MALT lymphoma

Metastatic lesion

Melanoma

Lung cancer

Breast cancer

Figure 3.152 BURKITT’S LYMPHOMA

A, B, Multiple nodular lesions, some of which resemble the esophageal lesions (see Figure 2.72).

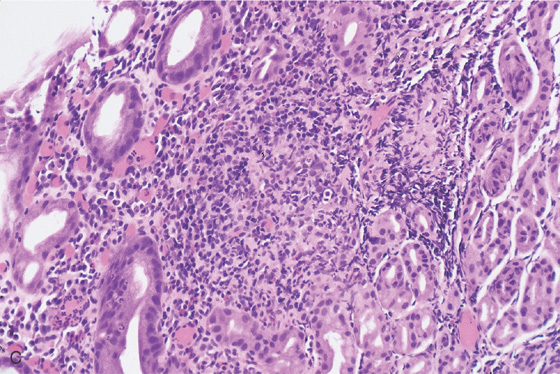

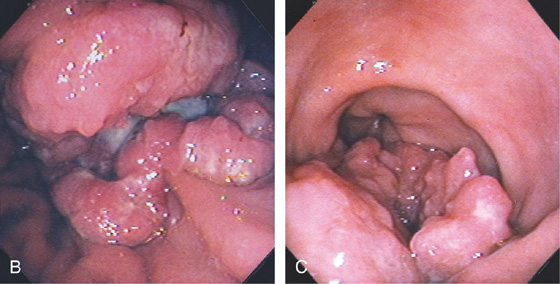

Figure 3.153 MUCOSA-ASSOCIATED LYMPHOID TUMOR (MALT) LYMPHOMA

Thickened gastric folds with scattered ulceration.

Figure 3.154 MUCOSA-ASSOCIATED LYMPHOID TUMOR (MALT) LYMPHOMA

Raised lesion of anterior gastric body.

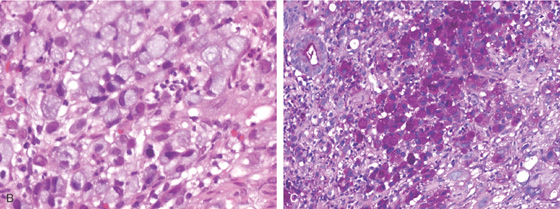

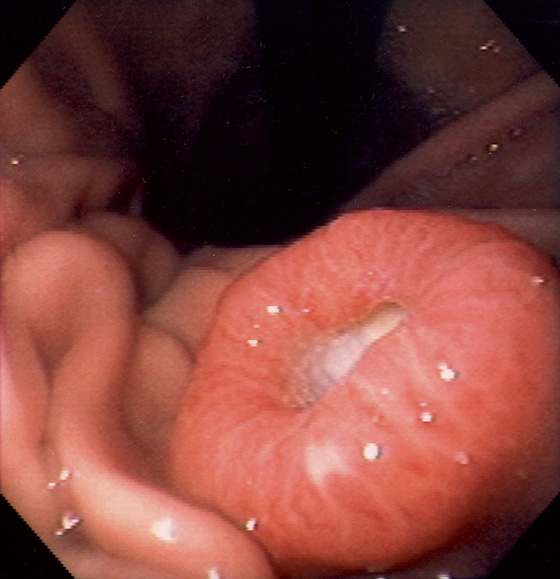

Figure 3.155 NEUROENDOCRINE CARCINOMA

Raised donut-like lesion with central ulceration.

Figure 3.156 KAPOSI’S SARCOMA

A, Large, confluent, plaquelike lesions. B, Multiple well-demarcated, violet-red lesions, some of which are flat and some elevated. C, With progression, they may form large ulcerated lesions, with the margins maintaining this violaceous red appearance. The lesion is well circumscribed, and the surrounding mucosa is normal. D, Multiple confluent polypoid lesions with a characteristic violaceous red appearance. E, Solitary round nodular lesion, central raised area, and indentation in the proximal stomach.

Figure 3.157 GASTROINTESTINAL STROMAL TUMOR (GIST)

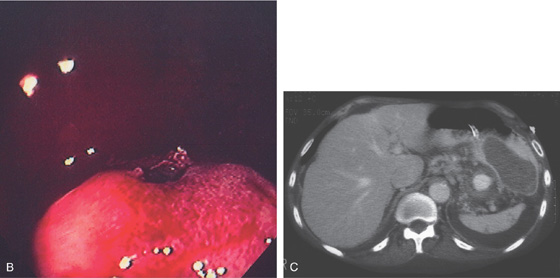

A, A masslike lesion resembling a thigh appears to be protruding from the gastric wall. An associated nodule is seen by the endoscope. The middle of the lesion has two ulcerations with spontaneous bleeding (inset). B, Sheets of malignant spindle cells.

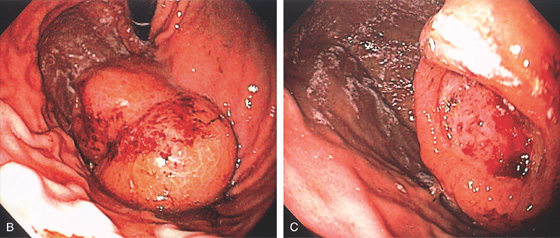

Figure 3.158 GASTROINTESTINAL STROMAL TUMOR (GIST)

A, Large luminal mass.

B, Large, masslike lesion of the proximal stomach with fresh hemorrhage. C, Close-up shows a well-circumscribed ulcer in the center of the lesion, the site of bleeding.

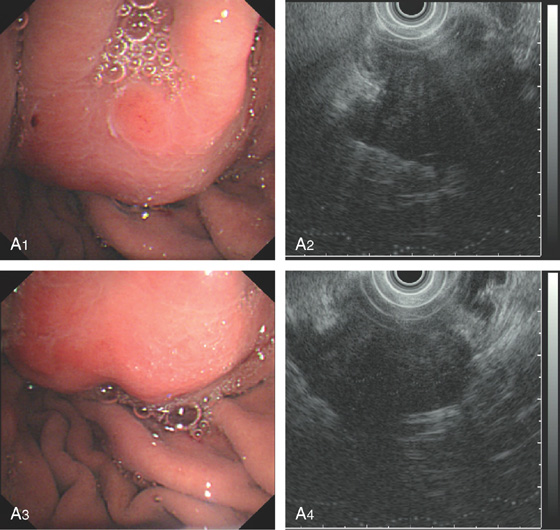

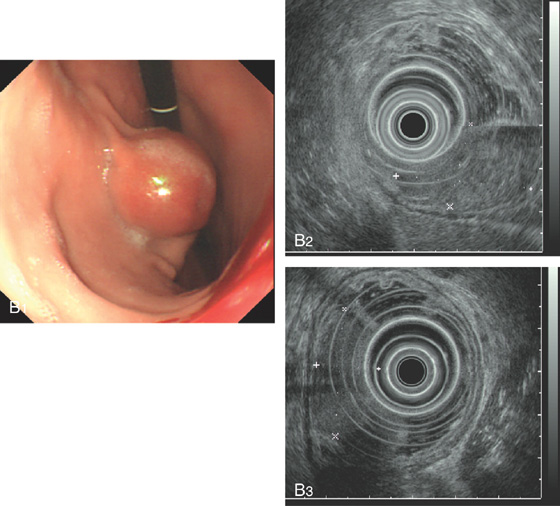

Figure 3.159 GASTROINTESTINAL STROMAL TUMOR (GIST)

A, Large lesion with central ulceration in the fundus. B, Round submucosal lesion in the fundus. C1, Submucosal lesion hanging from the GE junction. C2, EUS shows that the lesion arises from the muscle layer.

Figure 3.160 GASTROINTESTINAL STROMAL TUMOR (GIST)

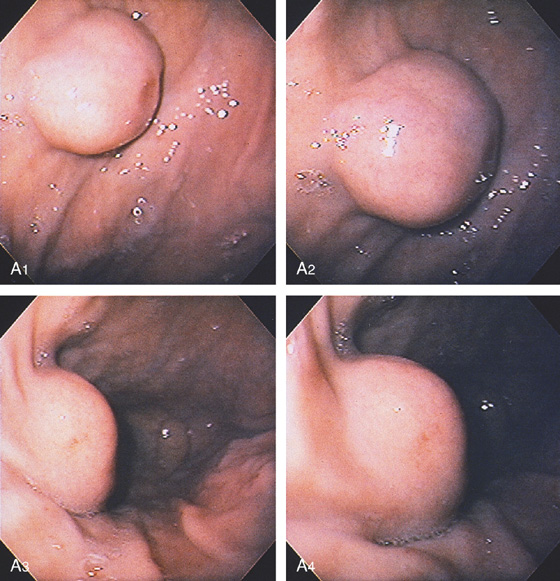

A1-A4, Gastrointestinal stromal tumor arising from the muscularis propria. The tumor is suspected to be malignant.

B1-B3, Gastrointestinal stromal tumor arising from the muscularis mucosae.

Figure 3.161 METASTATIC BREAST CANCER

Well-circumscribed raised lesion with central indentation in the gastric body.

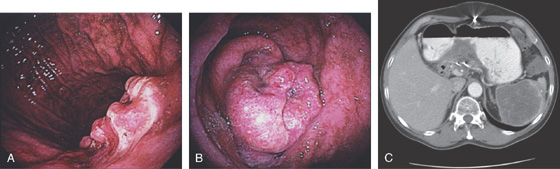

Figure 3.162 METASTATIC RECTAL CANCER

A, Well-circumscribed ulcerated lesion in the midbody posteriorly. The tumor extends into the antrum with a polypoid configuration (B). C, CT scan shows the large lesion invading the distal stomach.

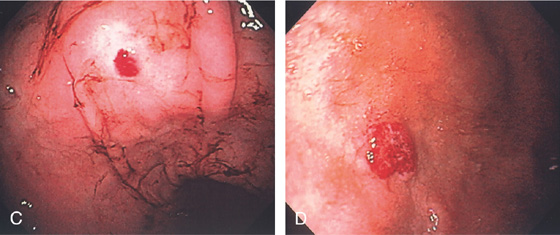

Figure 3.163 METASTATIC LUNG CANCER

Well-circumscribed elevated ulcerative lesion as seen on retroflexion. Evidence of recent bleeding is present.

Metastatic Lung Cancer (Figure 3.163)

Metastatic melanoma

Metastatic breast cancer

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor

Lymphoma

Figure 3.164 METASTATIC MELANOMA

A, B, Well-circumscribed raised (volcano) ulcerated lesion.

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Metastatic Melanoma (Figure 3.164)

Adenocarcinoma

Metastatic neoplasm, breast and lung

Gastric lymphoma

Figure 3.165 METASTATIC MELANOMA

A, Upper GI series shows raised lesion with central ulceration.

B, Multiple raised lesions with central ulceration.

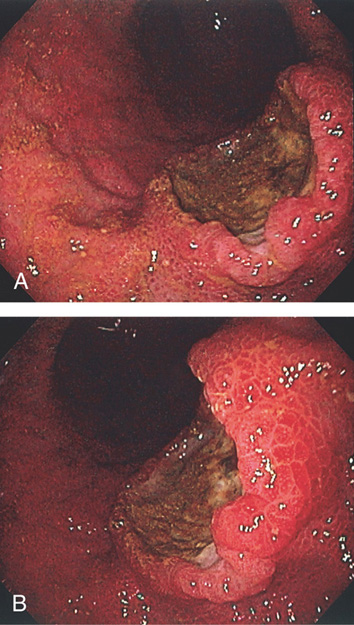

Figure 3.166 METASTATIC MELANOMA

A, Large, ulcerated, masslike lesions of the gastric antrum. B, Large ulcerated “kissing lesions” of the gastric antrum.

Figure 3.167 METASTATIC MELANOMA

A, Fundal mass. B, Nodular lesion with overlying exudate extending from the gastric fundus. C, Mass lesion representing a nodal mass at the pancreatic head impinging on the duodenum.

D, The mass is submucosal in nature. E, The bile duct stricture correlates well with the characteristics of the lesion.

F1, F2, Small black lesions typical for melanoma.

Figure 3.168 SQUAMOUS CELL CANCER AT THE SITE OF A PERCUTANEOUS ENDOSCOPIC GASTROSTOMY (PEG) TUBE

A, Ulceration is seen around the PEG tube. B, When the PEG tube is advanced inward, the large nodular lesion is seen. Biopsy confirms squamous cell cancer presumably seeding at the time of gastrostomy tube placement for squamous cell cancer of the esophagus.

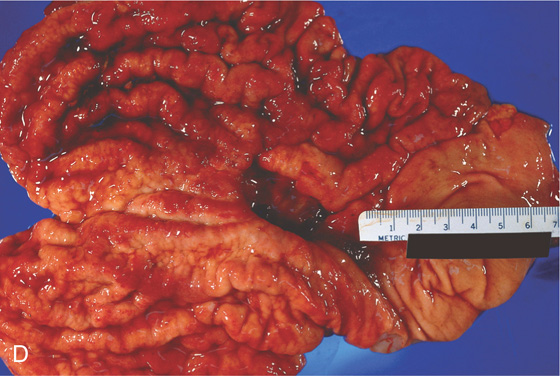

Figure 3.169 ZOLLINGER-ELLISON SYNDROME

A, Marked esophagitis. B, Markedly thickened gastric folds with a large amount of clear gastric fluid.

C, Multiple duodenal erosions. D, “Healthy” mucosa with prominent vascular pattern on the thick rugae.

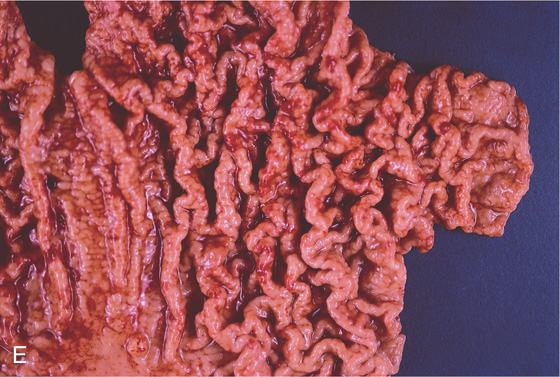

E, Surgical specimen shows the striking nature of the gastric rugae. The presence of esophagitis and duodenal erosions coupled with the gastric findings should strongly suggest the diagnosis.

Figure 3.170 ZOLLINGER-ELLISON SYNDROME

A, B, In this patient, the gastric folds were more pronounced and nodular, and the mucosa was hypervascular.

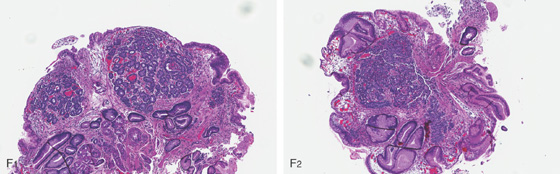

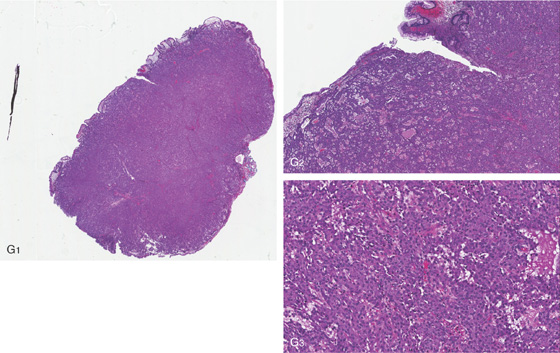

Figure 3.171 ZOLLINGER-ELLISON SYNDROME ASSOCIATED WITH MULTIPLE ENDOCRINE NEOPLASIA TYPE 1

A, CT scan performed for upper abdominal pain shows marked gastric fold thickening. B, Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) confirms the strikingly thickened gastric folds. C, In addition, multiple pancreatic tumors are present. D1, D2, The gastric folds are markedly thickened with numerous small overlying red polypoid lesions. D3, Some of the polyps are much larger and are ulcerated. Note even the very tiny red lesions are carcinoid tumors.

E, A hyperenhancing lesion is in the pancreatic tail corresponding to one of the lesions (gastrinomas) shown on EUS in C.

Figure 3.171 ZOLLINGER-ELLISON SYNDROME ASSOCIATED WITH MULTIPLE ENDOCRINE NEOPLASIA TYPE 1

F1, F2, Biopsy of one of the numerous small red circumscribed areas demonstrates nests of cells typical for a small carcinoid tumor (microcarcinoid) corresponding to the endoscopic lesions. Also note the marked subepithelial hemorrhage, which corresponds to the endoscopic appearance (D3).

G1, The large gastric polyp has been removed showing a carcinoid tumor. G2, Shallow ulceration is present on the mucosal surface, confirming the endoscopic impression. G3, The tumor is well differentiated and benign.

Figure 3.172 SYSTEMIC MASTOCYTOSIS

A, Marked thickening of the gastric rugae. B, Marked prominence of the area gastricae. C, Hyperpigmented skin lesions on the back termed urticaria pigmentosa.

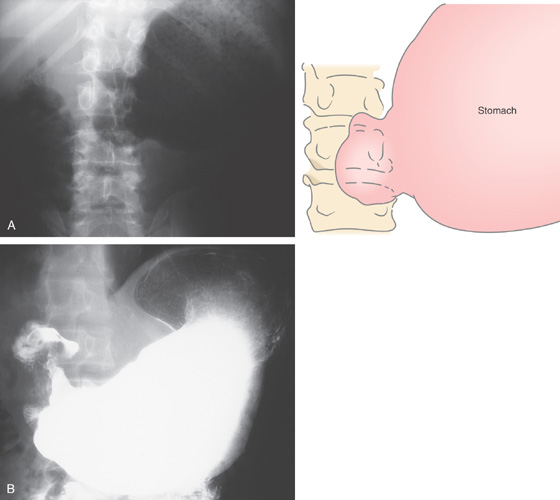

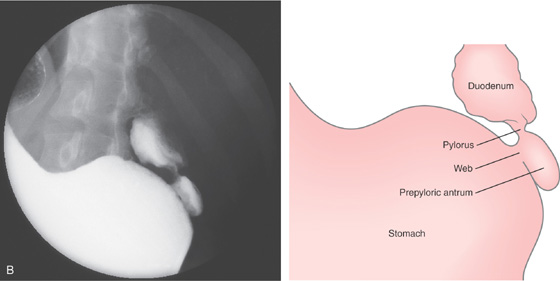

Figure 3.173 ANTRAL MUCOSAL DIAPHRAGM

A, A dilated stomach ends abruptly without evidence of ulceration or mass lesion.

B, A portion of stomach, as well as normal-appearing pylorus and duodenal bulb.

Figure 3.173 ANTRAL MUCOSAL DIAPHRAGM

C, A semicircular ring demarcates the abrupt end of the stomach (C1, C2). In the middle of this semicircular fold is a pinhole opening (C3). The endoscope could not be advanced through this area. There is associated reflux esophagitis resulting from the gastric outlet obstruction (C4).

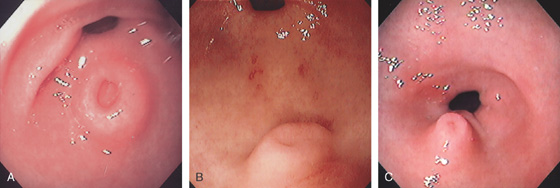

Figure 3.174 ANTRAL RING

A, Segmental area of nodular annular narrowing in the distal antrum. The proximal and distal portions of the antrum appear normal, as does the duodenal bulb. B, Ringlike abnormality with apparent mucosal thickening surrounding the area. C, Close-up view of the ring demonstrates normal-appearing mucosa, with the antrum and pylorus in the distance.

Figure 3.175 BILLROTH I ANASTOMOSIS

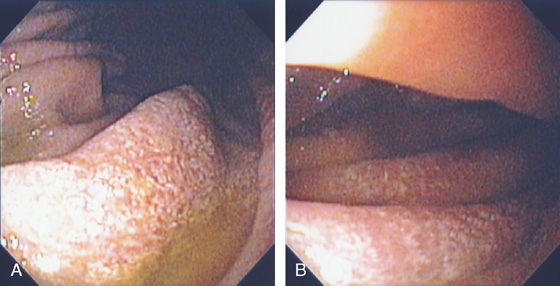

The gastric remnant appears somewhat atrophic (A, B). The anastomosis is visible at the level of the angularis and is widely patent, with suture material present (C, D).

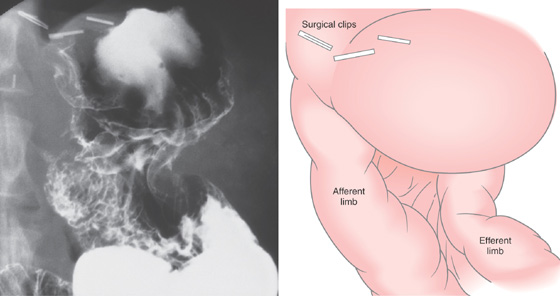

Figure 3.176 BILLROTH II ANASTOMOSIS

Gastric remnant with both small-bowel limbs visible.

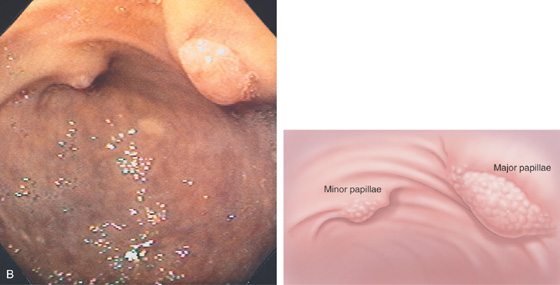

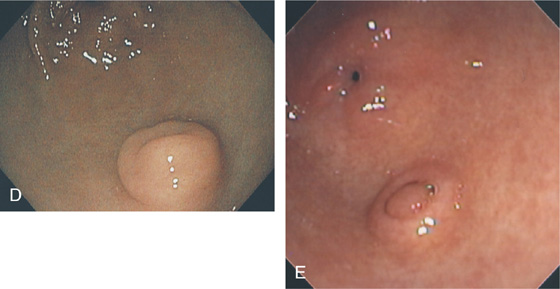

Figure 3.177 BILLROTH II ANASTOMOSIS

A, Diffuse erythema is present in the distal gastric remnant. Multiple yellow plaques represent xanthelasma (A1, A2). Both afferent and efferent limbs are at the anastomosis (A3, A4). The afferent limb is on the right and the efferent on the left.

B, At the end of the afferent limb, the major and minor papillae are shown.

Figure 3.178 GASTROJEJUNOSTOMY

A, The jejunum is anastomosed to the posterior gastric body. Ulceration around the anastomosis is frequent in the immediate perioperative period. B, Note the relationship of the anastomosis to the antrum seen to the right. C, Widely patent anastomosis. D1, In a patient with prior Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, the gastric pouch is seen from the gastroesophageal junction. D2, The gastric pouch is small and the small-bowel limbs are visible. D3, Both small-bowel limbs are shown.

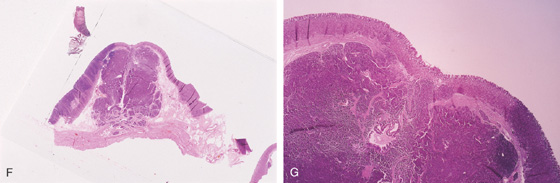

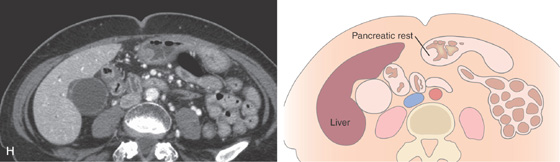

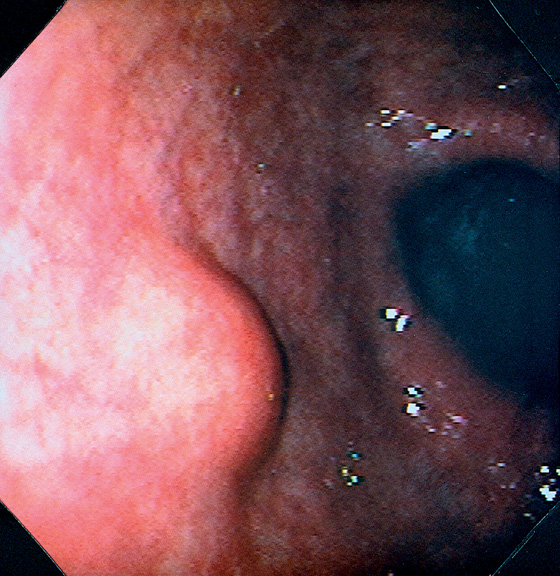

Figure 3.179 PANCREATIC REST

Variable appearance of a pancreatic rest (A-E).

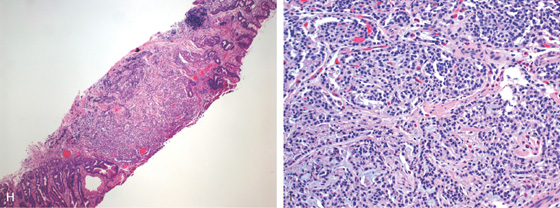

F, G, Pancreatic tissue present in this submucosal lesion.

H, CT scan shows a small lesion corresponding to D.

Figure 3.180 EXTRINSIC LESION

A, A multilobed nodular lesion is seen pushing into the gastric body anteriorly. The nodular lesion was manipulated with a closed biopsy forceps and found to be hard. B, Multiple metastatic lesions in the liver. A large lesion in the left lobe is impinging on the stomach, corresponding to the area of extrinsic compression.

Figure 3.181 EXTRINSIC LESION

Round, well-circumscribed lesion in the anterior gastric body. The overlying mucosa is normal. When the lesion was probed with the closed biopsy forceps, it moved freely and was firm. This lesion might be a benign submucosal lesion, malignant submucosal lesion, or extrinsic lesion such as a lymph node.

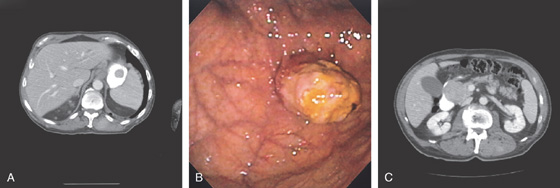

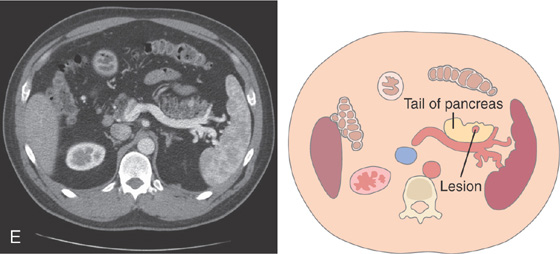

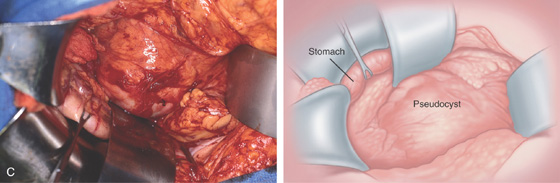

Figure 3.182 EXTRINSIC LESION: PANCREATIC PSEUDOCYST

A, Large pseudocyst in the tail of the pancreas, causing compression on the posterior gastric wall.

B1-B4, Extrinsic compression occurring posteriorly in the proximal stomach.

C, Large pseudocyst and its relationship to the stomach.

Figure 3.183 PSEUDOCYST CAVITY AFTER SURGICAL CYST GASTROSTOMY

A, Widely patent anastomosis to the cyst cavity. B, Marked nodularity and exudate representing the pseudocyst cavity. C, Cavity entered from stomach.

Figure 3.184 PRIOR SURGICAL CYST GASTROSTOMY

A1, A2, Large adherent exudate on the posterior gastric wall. B1, B2, After removal of some of the exudate, the endoscope was passed through an opening into a large cavity representing the pseudocyst (C1-C3).

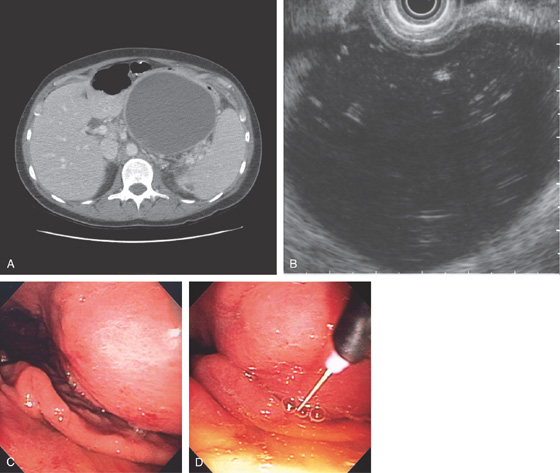

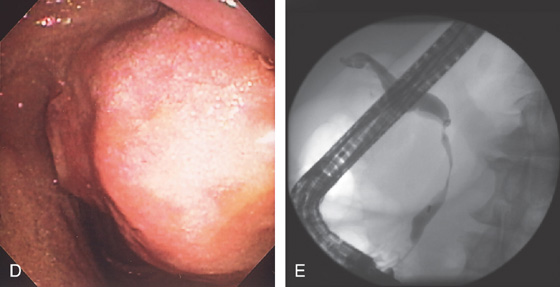

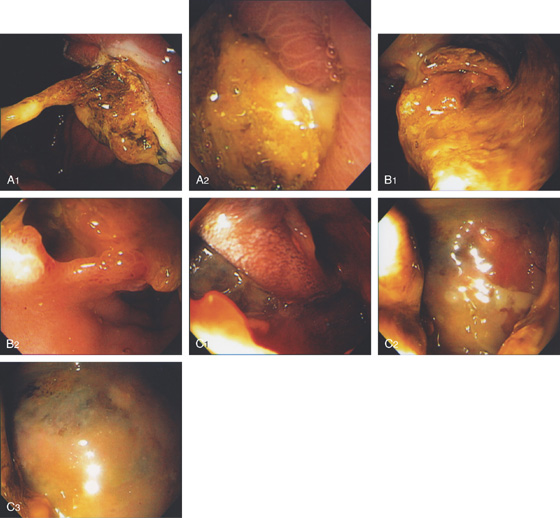

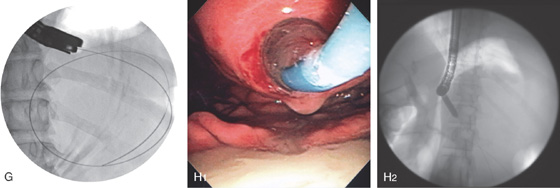

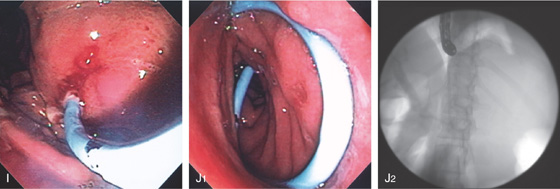

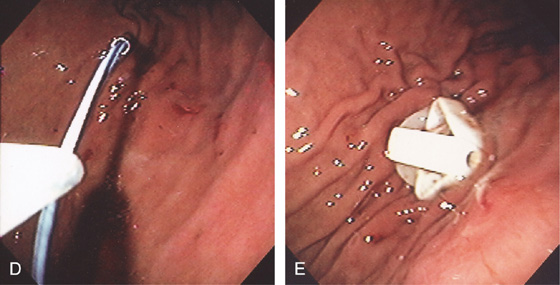

Figure 3.185 ENDOSCOPIC CYST GASTROSTOMY

A, Large retrogastric fluid collection. Note the stomach is compressed. B, The cyst cavity is large and contains some internal echoes suggestive of debris. C, A large bulge is along the posterior gastric wall. D, The needle knife is exposed.

Figure 3.185 ENDOSCOPIC CYST GASTROSTOMY

E1, E2, The cyst is punctured and deeply entered, as confirmed by aspiration of cyst contents. F, With the catheter removed, purulent material is seen draining around a guidewire, which has been coiled in the cyst cavity

(G). H1, H2, The cyst wall is dilated with a balloon.

I, A 10-French pigtail stent is being advanced into the cavity. J1, J2, The double pigtail stent has been deployed.

Figure 3.186 EXTRINSIC LESION

A, Round, masslike lesion in the proximal gastric body. An area of depression is at the apex (A1). Both antegrade (A1, A2) and retroflex (A3, A4) views suggest an extrinsic lesion. The overlying mucosa is normal.

B, The mass lesion appears in the lumen, making differentiation between an extrinsic and an intrinsic lesion difficult. C, Endoscopic ultrasonography shows the mass lesion with all layers of the mucosa intact and displaced, suggesting an extrinsic lesion.

Figure 3.187 EXTRINSIC LESION: DILATED GALLBLADDER

A1, A2, Extrinsic compression of the gastric antrum anteriorly.

B, Large, fluid-filled stricture represents the gallbladder.

Figure 3.188 EXTRINSIC LESION: PANCREATIC CANCER

A, Mass lesion extending from the pancreas to the posterior wall of the stomach.

B1, B2, Raised donut-like lesion with large central ulceration.

Figure 3.189 EXTRINSIC LESION: COLONIC CARCINOMA

A, Masslike lesion in the left upper quadrant involving the posterior wall of the stomach, as well as kidney.

B, C, Focal area of thickened gastric folds with recent bleeding as seen on both antegrade (B) and retroflex (C) views.

Figure 3.190 EXTRINSIC LESION: METASTATIC LUNG CANCER

A, Large mass involving left kidney with involvement of the posterior gastric wall.

B, Ulcer on top of the mass. C, Retroflex view shows extrinsic compression.

Figure 3.191 EXTRINSIC LESION: SPLENIC ARTERY PSEUDOANEURYSM

A, Extrinsic lesion in the proximal stomach.

B, Close-up of the center of the lesion shows an ulceration with fresh blood clot. C, Vascular lesion posterior to the stomach representing a pseudoaneurysm. Old blood is seen in the gastric wall.

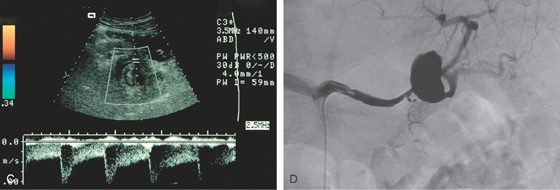

Figure 3.192 EXTRINSIC LESION: SPLENIC ARTERY ANEURYSM

A, Extrinsic masslike lesions involving the posterior wall as shown on retroflexion. B, Large hematoma involving the posterior wall of the stomach, with fresh hemorrhage represented by contrast extravasation.

C, Doppler ultrasound shows flow in the lesion. D, Angiography demonstrates an aneurysm of the splenic artery.

E, Embolization of the lesion was performed successfully. Coils now present with no blood flow.

Figure 3.193 GASTRODUODENAL FISTULA

Two openings are in the gastric antrum (A). If the superior opening is entered, an obstructed duodenal bulb is shown (B). If the endoscope enters the inferior opening, ulceration is shown, with an entrance distally (C). With further advancement, the second portion of the duodenum is visualized (D).

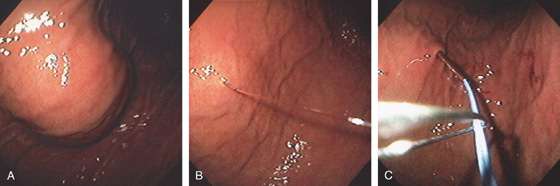

Figure 3.194 PERCUTANEOUS ENDOSCOPIC GASTROSTOMY (PEG) PLACEMENT

A, The anterior wall is palpated with a finger easily compressing the anterior gastric wall. B, The needle is passed into the gastric wall with injection of lidocaine. C, Through the needle, a wire is passed and grasped with a snare.

D, The wire is removed. E, The bumper of the PEG tube is visible along the anterior gastric wall.

Figure 3.195 BLEEDING GASTRIC ULCER CAUSED BY PERCUTANEOUS ENDOSCOPIC GASTROSTOMY (PEG) TUBE

A1, A2, Ulcer on the contralateral (posterior) wall caused by repetitive PEG tube trauma.

B, Large deep ulcer on the posterior wall opposite a G-tube as seen on retroflexion. C, Black eschar with surrounding serpiginous ulceration.

Figure 3.196 BLEEDING FROM PERCUTANEOUS ENDOSCOPIC GASTROSTOMY (PEG) TUBE

A, The G tube is covered with blood clot. B, With advancement of the G-tube, active bleeding can be seen from the abdominal wall. C, A sclerotherapy needle is placed into the anterior wall of the stomach with injection of a large volume of dilute epinephrine. D, Marked ischemia of the gastric wall with hemostasis.

Figure 3.197 BURIED BUMPER

A, A round defect is present in the anterior gastric wall. B, CT shows the PEG in the anterior abdominal wall separate from the gastric lumen.

Figure 3.198 SURGICAL GASTROSTOMY TUBE SITE

Two metallic sutures are present in the area of a prior surgical gastrostomy tube placement. The gastric folds are pulled up to the areas of suturing.

Figure 3.199 PRIOR GASTROSTOMY TUBE SITE

A, Well-healed area with retraction and central indentation.

Figure 3.199 PRIOR GASTROSTOMY TUBE SITE

B, The gastrostomy tube was removed 1 week before endoscopy. An ulcer is present at the center of the old site (B1-B3). Extrinsic compression at the scar on the abdominal wall indicates the old site (B4).

C1, C2, Ulcerated area of the anterior gastric wall representing a recently removed G-tube site. C3, A snare has been placed through the site and out through the skin. C4, The snare is then used to grasp the guidewire, which is then withdrawn through the stomach and oropharynx for subsequent PEG replacement.

Figure 3.200 GASTRIC XANTHELASMA

A, Yellow plaque in the distal gastric body. B, Yellow, well-circumscribed polypoid lesion on the anterior wall of the gastric body. C, Foamy macrophages can be identified.

Figure 3.201 MÉNÉTRIER’S DISEASE

A, Irregularly thickened gastric folds. B1-B4, Multiple gastric polyps beginning at the gastroesophageal junction and extending to the antrum. Mucus was seen to exude from the polyps, as well as frank bleeding. Biopsy of the polyp showed striking foveolar hyperplasia. This patient had chronic iron-deficiency anemia and hypoalbuminemia. C, Multiple polyps of the proximal stomach.

Foveolar hyperplasia (D1) associated with dilated cystic areas (D2).

Figure 3.202 AMYLOID

A, Scattered petechial hemorrhage of the gastric antrum, which appears slightly yellow. B, Subepithelial hemorrhage with minimal abnormalities of the surrounding mucosa. C, Markedly thickened nodular antral folds with fresh hemorrhage. D, Amorphous material fills the submucosa. E, Congo red stain highlights the submucosal material, confirming the diagnosis.

Figure 3.203 PSEUDOMELANOSIS

A, Black pigmented lesions throughout the gastric antrum. This patient also had pseudomelanosis duodena (B). (See Figure 4.102.)

Figure 3.204 CALCINOSIS

A, B, The gastric folds have a whitish thickened appearance in this patient with renal failure on dialysis.

C1, Benign gastric mucosa with mild edema, inflammation, and multifocal areas of amorphous calcifications present in vascular and extravascular spaces.

C2, Benign gastric mucosa with mild edema, inflammation, and multifocal areas of amorphous calcifications present in vascular and extravascular spaces.

Figure 3.205 BAROTRAUMA

A, Multiple linear lesions throughout the gastric body. B, Close-up shows a linear tear and fresh bleeding.

Figure 3.206 NONSPECIFIC ABNORMALITIES

A, Diffuse erythema, subepithelial hemorrhage, and fresh heme. B, Multiple red linear lesions. Biopsy in both cases disclosed no specific cause. Such findings are often attributed to “gastritis.” C, Diffuse hemorrhage of the gastric mucosa of unclear cause.

Figure 3.207 PRIOR EMBOLIZATION COIL

A, In the gastric antrum, a blue structure is emanating from an indentation. B, This is a prior coil from embolization of an artery in the setting of a bleeding pseudocyst.

Figure 3.208 FOREIGN BODY

A, Battery. B, Plastic pill container. C1, C2, Collard greens. D1, D2, Whole pecan. E, Black-eyed pea.