Chapter 11 State and territory medicines legislation

THE GALBALLY REVIEW

In 2001 Ms Rhonda Galbally completed her review of the drugs and poisons legislation in Australia, titled Review of Drugs, Poisons & Controlled Substances Legislation.[1] The Galbally Review, as it is known, examined Australian state and territory legislation regulating medicines and poisons against national competition principles. The report made 22 recommendations aimed at achieving national uniformity of drugs and poisons legislation through legislative reform. In relation to scheduled medicines for human use, most of the recommendations were implemented by 2006–2007.

The Galbally Review was submitted to the Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council (AHMAC) which established a working party to assist in the preparation of a report. The working party recommended the adoption of all the recommendations (with some minor amendments) with the exception of Recommendation 7, which was concerned with administrative arrangements for scheduling.[2] At the time the report was written, discussions between Australia and New Zealand for a Trans-Tasman Joint Agency for the regulation of therapeutic goods had begun. It was felt that any changes to the scheduling arrangements in Australia should hinge on, and be harmonious with, arrangements for the joint agency. The discussions relating to the joint agency have been suspended.

Arguably the most contentious proposal in the Galbally Review was contained in Recommendation 5 which suggested if there was no evidence to support the retention of Schedules 2 and 3 as currently appearing in the Standard for the Uniform Scheduling of Drugs and Poisons (SUSDP) then the schedules should be combined with new criteria to be developed. A report on Recommendation 5 was submitted to the AHMAC by the National Coordinating Committee on Therapeutic Goods (NCCTG).[3] The AHMAC endorsed the report and agreed to continue the scheduling arrangements for S2 (Pharmacy) and S3 (Pharmacist Only) medicines for an interim period of 5 years, subject to a further demonstration that the existing system delivered positive outcomes for health consumers.

The research for the NCCTG was undertaken by academics from the University of Sydney, the University of South Australia, and the University of Queensland together with external consultants.[4] The NCCTG report to AHMAC was based on the results of this research, stating that:[3]

The NCCTG report also expressed concern that there was a potential for ‘… the research methodology to skew the results of the epidemiology study as it relied on participants being self-selected rather than being selected at random …’.[3] It also noted that the results of the ‘Mystery Shopper Program’ showed there were a significant number of pharmacists who did not comply with provisions of the Standards for the Provision of Pharmacy Medicines and Pharmacist Only Medicines in Community Pharmacy.[3] The NCCTG report also stated there appeared to be ‘… considerable disparity in the level of counselling delivered and in some cases of supplying S3 medicines where no counselling had been delivered at all’.[3] This was identified with some level of concern as the lack of counselling not only did not comply with the S2/S3 Standards but was also in breach of state and territory drug legislation.

SCHEDULING

As discussed in Chapter 10, the SUSDP is defined pursuant to section 52A of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1987 (Cth) and gives effect to the decisions of the National Drugs and Poisons Scheduling Committee (NDPSC) regarding the classification of drugs and poisons into schedules for inclusion in the relevant state and territory legislation. The SUSDP also includes model provisions for containers and labels, a list of products recommended to be exempt from those provisions, and recommendations about other controls on drugs and poisons. It is presented with a view to promoting uniform scheduling of substances and uniform labelling and packaging requirements throughout Australia. The decisions of the NDPSC have no force in Commonwealth law but were recommended for incorporation into state and territory legislation by the Galbally Review. This has been achieved in all states and territories. However, as mentioned in the introduction, most state- and territory-based legislation has the power to vary a scheduling arrangement for any poison should the relevant Health Minister decide not to adopt a recommendation of the NDPSC.

The SUSDP defines a ‘poison’ as ‘… any substance or preparation included in a Schedule to the Standard’ while a ‘drug’ means ‘… a poison intended for human or animal therapeutic use’.[5] It is worthy to note that the term ‘drug’ is increasingly being replaced in many official documents — although not in the SUSDP — by the term ‘medicine’ or ‘substance’. One reason for this change could be the negative connotations associated with the term ‘drug’ as it is often used in association with illegal use and trafficking; for example, ‘drug abuse’, ‘drug baron’, ‘drug mule’, ‘drug bust’, ‘druggie’, and ‘to do drugs’.

The Introduction to the SUSDP and the first three Parts are discussed in Chapter 10. Part 4, The Schedules, are as follows:[5]

There are 11 appendices to the SUSDP and these are listed in Chapter 10.

Generally speaking, drugs and poisons legislation regulates the manufacture, production, sale, supply, possession, handling or use of poisons (including drugs and therapeutic and other substances) and certain therapeutic devices. The legislation also authorises some health professionals to undertake certain dealings in relation to poisons. Table 11.1 lists the main legislation in each of the states and territories relating to the control of drugs and poisons.

| State | Act | Regulation |

|---|---|---|

| Australian Capital Territory | Medicines, Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Act 2008 | Medicines, Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Regulation 2008 |

| New South Wales | Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Act 1996 | Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Regulation 2008 |

| Northern Territory | Poisons and Dangerous Drugs Act | Poisons and Dangerous Drugs Regulations |

| Queensland | Health Act 1937 | Health (Drugs and Poisons) Regulation 1996 |

| South Australia | Controlled Substances Act 1984 | Controlled Substances (Poisons) Regulations 1996 |

| Tasmania | Poisons Act 1971 | Poisons Regulations 2002 |

| Victoria | Drugs, Poisons and Controlled Substances Act 1981 | Drugs, Poisons and Controlled Substances Regulations 2006 |

| Western Australia | Poisons Act 1964 | Poisons Regulations 1965 |

Note: The Northern Territory does not include the date in the title of this legislation.

The following is a general overview of the relevant legislation enacted in the states and territories in regard to the practice of pharmacy. In familiarising themselves with drugs and poisons legislation in the various jurisdictions pharmacists should pay particular attention to:

Australian Capital Territory

The medicines and poisons standard refers to the Poisons Standard in the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth) which references the latest edition of the Standard for the Uniform Scheduling of Drugs and Poisons (SUSDP) — as defined in section 52A. The Poisons Standard is prepared or amended by the National Drugs and Poisons Schedule Committee pursuant to section 52D (2) of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth).

New South Wales

Part 2 of the Act addresses the Poisons Advisory Committee and the Poisons List. The membership of the committee and its procedures are identified in this Part of the Act. There are 16 members of the committee. Six members are nominated (one being the Head of the Department of Pharmacy, University of Sydney, or a delegate) while the remaining 10 members are appointed by the Governor. Of these, one is a representative of the Pharmacy Guild of Australia (NSW branch) and one is a representative of the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia (NSW branch). The two functions of the committee are, firstly, to make recommendations regarding the making, altering or repealing of any regulation under the Act and, secondly, make recommendations for amending the Poisons List.

For the purposes of the scheduling of poisons, New South Wales has adopted the New South Wales Poisons List which is a list proclaimed under section 8 of the Act.[6] The Poisons List may be amended by applying, adopting or incorporating, with or without modification, the current Poisons Standard within the meaning of Part 5B of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth). The effect is to adopt the SUSDP as amended (with any New South Wales variations) as the Poisons List. In the current Poisons List, Schedule 2 has a variation to the entry for codeine when compounded in preparations containing 10mg or less of codeine, where the restriction on a primary pack containing 25 dosage units or less in the SUSDP has been removed.[4] Likewise, Schedule 3 also includes a variation to the entry to codeine. There are also two additions to Schedule 8 poisons listed in the SUSDP, etorphine and tetrahydrocannabinol and its alkyl homologues, except:

The clause goes on to identify exceptions to this requirement including those cases in which the supply is to other authorised persons and in some first aid or other emergency situations. Although there is no general requirement to record the supply of Schedule 3 substances, a pharmacist who supplies pseudoephedrine must record details of supply as if it were a Schedule 4 medicine.

The holder must be informed in writing and must be given reasonable opportunity to make representation with respect to the proposed suspension or cancellation.

Northern Territory

Prescriptions are dealt with in Part 6, which applies to all prescriptions issued by a medical practitioner, dentist, optometrist or veterinarian for the supply of a Schedule 1, 4, 7, or 8 substance. Prescriptions are valid for a period of 12 months, other than for Schedule 8 substances, which are valid for 2 months and must not provide for more than 2 months supply unless specific approval is obtained from the Chief Health Officer. Section 35 requires pharmacists to endorse prescriptions after dispensing while section 36 requires that the details of each prescription dispensed be recorded. Section 37 makes provision for the emergency supply of scheduled substances.

Queensland

In addition, recent amendments to the Regulation impose quality standards for dispensing certain drugs and selling certain poisons. These standards are recognised by the Pharmacists Board of Queensland and are available on the board’s website at www.pharmacyboard.qld.gov.au. Under section 4A(4) such standards must be consistent with the following principles:

Chapter 2 of the Regulation deals with controlled (Schedule 8) drugs and includes sections on: licences; the issuing of particular endorsements; regulated controlled drugs; prescribing and dispensing; obtaining and selling; possession and storage; records; and treatment with, and dependence on, controlled drugs. The specific provisions relating to the labelling and recording are dealt with in Part 4 of this chapter. The section also deals with additional restrictions placed on the regulated controlled drugs dronabinol, amphetamine, dexamphetamine, methylamphetamine, methylphenidate and phenmetrazine. The chapter also covers the requirements regarding verbal prescriptions.

Chapter 3 covers prescription only (Schedule 4) medicines and is similar in structure to that pertaining to controlled drugs. It includes a section on the additional restrictions placed on regulated restricted drugs as included in Appendix D in the SUSDP. Also included are matters relating to the supply and recording of Prescription Only medicines as an emergency supply.

Chapter 4 addresses poisons including the endorsements needed to obtain, dispense, possess and sell Schedule 2, 3 and 7 poisons. Pharmacists, to the extent necessary to practise pharmacy, are endorsed to dispense, supply or sell S2, S3 or S7 poisons at a dispensary (s257) as long as they have prepared or adopted a relevant quality standard (s273A).

It has been recognised for a number of years that the sale of pseudoephedrine-containing products, predominantly Schedule 3, has presented particular problems because of the diversion of some of the purchased product to the illicit production of amphetamine-like substances. In an effort to minimise this diversion additional controls have been placed on the sale of pseudoephedrine-containing products through amendments to the Regulation. The subject of diversion has been discussed in a number of Pharmacist Board of Queensland Bulletins.[7]

South Australia

The Regulations declare that poisons listed in Schedule 4 and Schedule 8 are ‘prescription drugs’, and poisons listed in Schedule 8 are ‘drugs of dependence’. In addition, any substance either approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) for inclusion in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods or by the National Registration Authority of the Commonwealth for inclusion in the Australian Register of Agriculture and Veterinary Chemical Products will be taken to be a Schedule 4 poison unless otherwise scheduled or specifically exempt.

Tasmania

The Poisons Act 1971 (Tas) is an Act:

[T]o make provision with respect to the regulation, control, and prohibition of the importation, making, refining, preparation, sale, supply, use, possession, and prescription of certain substances and plants and matters incidental thereto.

Part 5, Packaging and Labelling of Therapeutic Substances, recognises the SUSDP and imposes its requirements.

Victoria

Under section 13 a pharmacist is an authorised person and is authorised:

Other parts of the Act include:

Part 4 covers the matter of Schedule 3 poisons. Under the legislation a pharmacist is required to supply a Schedule 3 poison only where he or she has taken all reasonable steps to ensure a therapeutic need exists for that substance (s61). In a pharmacy Schedule 3 poisons must not be stored in such a way that allows self-selection by the public (Regulation 62). The pharmacist is required to personally supervise the sale, provide directions for the use of the substance and place a label on the container that identifies the supplier (Regulation 63).

Western Australia

Part 4, Drugs of addiction, deals with the general provisions that apply to Schedule 8 medicines.

Part 5, Sale, Supply and Use, includes general restrictions and sections relating to Schedule 3 and 4 poisons. Schedule 3 substances can only be sold under the direct personal supervision of a pharmacist and only after all reasonable steps have been taken to ensure there is a therapeutic need for the substance (s38A). The sale of Schedule 3 poisons must be recorded and the product labelled with the name and address of the pharmacy and a unique sale identification number. In the case of pseudoephedrine, the purchaser must give photographic evidence of his or her identity unless personally known to the pharmacist. Records of the sale of Schedule 3 poisons must be kept for a minimum period of 2 years and Schedule 3 substances must be stored in such a manner inaccessible to the general public. The Regulations also preclude the advertising of Schedule 3 and Schedule 4 substances other than that which is permitted by the SUSDP. The one exception are substances contained in a pregnancy testing kit which may be advertised.

PSEUDOEPHEDRINE

Pseudoephedrine is an oral sympathomimetic decongestant that acts on alpha- adrenoreceptors and vascular smooth muscles in the respiratory tract producing vasoconstriction of dilated nasal vessels reducing tissue swelling and nasal congestion.[8] However, it was not its pharmacological activity that thrust it into the scheduling spotlight from the late 1990s onward, but rather the fact that it was a precursor to methylamphetamine, also known as ‘speed’ or ‘ice’. There has been a marked increase in the use of methylamphetamine, a stimulant that can be snorted, swallowed, injected or smoked, with 9.1% of Australians reporting having used the drug.[9] It has been estimated that there are approximately 76 000 dependent methylamphetamine users in Australia — almost double the estimated number of heroin users.

It was the diversion of significant quantities of pseudoephedrine purchased through community pharmacies into the area of illicit drug manufacture that was a major stimulus to the up-scheduling of pseudoephedrine, from Schedule 2 (Pharmacy medicine) in the 1990s, to Schedule 3 (Pharmacist Only medicine) and Schedule 4 (Prescription Only medicine) in 2006. Prior to the inclusion of pseudoephedrine products in Schedule 3 in 2006 the larger packs of the single product (pseudoephedrine 60mg tablets) were moved from Schedule 2 to Schedule 4. This move could be seen as a failure of the profession to follow good practice standards and guidelines. In 1998 seminal work undertaken by the Department of Pharmacy, University of Sydney and the School of Pharmacy and Medical Sciences, University of South Australia, supported by funding from the then Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services, resulted in the development of Standards for the provision of Pharmacy medicines and Pharmacist Only medicine in community pharmacy. However, despite the wide dissemination and support for the standards together with advice and warnings from regulatory authorities, a significant number of pharmacists continued to supply pseudoephedrine in larger sizes (60s and 100s) with little regard for their professional responsibilities or duty of care.

When it became apparent that large-scale diversion of pseudoephedrine into the area of illicit drug manufacture was taking place, there were suggestions from regulatory authorities that one way to minimise the problem would be to reschedule pseudoephedrine to a Schedule 4 Prescription Only medicine. This suggested solution was vigorously opposed by industry and to a lesser extent the pharmacy profession on the basis that any such re-scheduling would seriously disadvantage thousands of Australian who had a therapeutic need for pseudoephedrine. There was also no compelling evidence that such a move would curtail the spread of illegal drugs.[10]

In addition, the Pharmacy Guild of Australia developed ‘Project STOP’.[11] This is a decision-making tool for pharmacists aimed at minimising the use of pseudoephedrine-based products for methylamphetamine manufacture by recording sales of pseudoephedrine-containing products to allow tracking, identification and blocking of ‘pseudoephedrine runners’. These runners visit multiple pharmacies over a short period of time. Project STOP is based on an online tool that provides decision-making support to pharmacists who need to establish whether a request for pseudoephedrine-based product is legitimate. The database allows the recording of the identification card number provided by the potential purchaser and the product and the quantity requested. The database provides the pharmacist with information regarding the purchase history associated with the identification card number and a decision can then be made whether or not to conclude the sale. The database then records whether or not the sale was made. The database was originally developed in Queensland and rolled-out nationally in 2007.

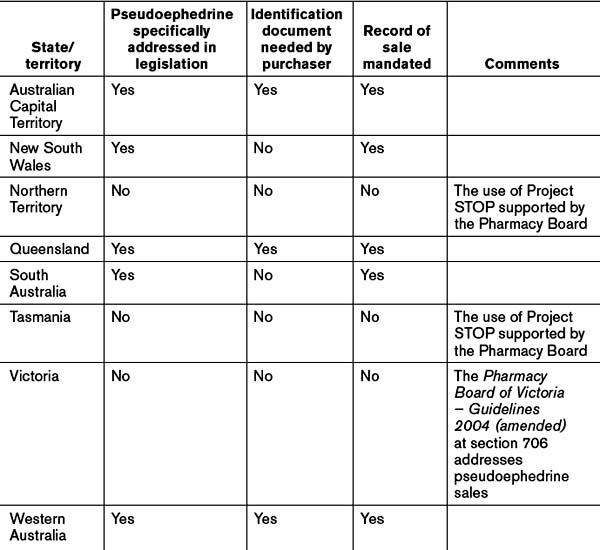

At the time of writing the uptake of Project STOP Australia-wide stood at 67.13%, ranging from New South Wales at 49.71% to the ACT and Northern Territory at 100%.[12] Refer to Table 11.2 for a summary of controls on pseudoephedrine sales.

Australian Capital Territory

The ACT addresses the selling of pseudoephedrine in division 4.2.7 of the Medicines, Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Regulations 2008 (ACT). Section 172 requires the pharmacist to inform the purchaser that the pharmacist is required to make a record of the sale. And the sale record may be made available to certain persons including police officers. If the purchaser refuses to provide certain information the sale cannot be concluded. The purchaser has the right to see the record and have any mistakes corrected.

South Australia

Pseudoephedrine appears in the Controlled Substances (Poisons) Regulations 1996 (SA) in Schedule G, which lists those Schedule 3 poisons to which section 14(2) applies. Section 14 requires a person who sells or supplies a Schedule 3 substance to give oral directions together with written directions for the safe and proper use of the substance, and also to record the name and address of the purchaser, the date of the transaction, the directions given, and apply an identifying number to the record. A copy of all such records must be lodged with the State Health Department within 15 days from the end of the month.

Council of Australian Governments (COAG). Review of Drugs, Poisons and Controlled Substances Legislation. Canberra: COAG; 2001.

Pharmacy Guild of Australia. A cost-benefit analysis of Pharmacist Only (S3) and Pharmacy Medicines (S2) and risk-based evaluation of the standards. Canberra: Pharmacy Guild of Australia, June 2005.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Statistics on Drug Use in Australia 2006. Canberra: AIHW; 2006.

1. Galbally R, Council of Australian Governments. Review of Drugs, Poisons and Controlled Substances Legislation. January 2001. Online. Available: www.tga.gov.au/DOCS/pdf/rdpfina.pdf [accessed 30 October 2008]

2. Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council Working Party. Response to the review of drugs, poisons and controlled substances legislation (the Galbally review). April 2003. Online. Available: www.tga.health.gov.au/docs/pdf/rdpahmac.pdf [accessed 3 November 2008]

3. National Coordinating Committee on Therapeutic Goods. A report to the Australian Health Ministers’ Conference on the results of research into a cost benefit analysis of Pharmacist only (S3) and Pharmacy medicines (S2) and risk-based evaluation of the standards. August 2005. Online. Available: http://tga.health.gov.au/meds/s2s3report.htm [accessed 3 November 2008]

4. Pharmacy Guild of Australia. A cost-benefit analysis of Pharmacist only (S3) and Pharmacy medicines (S2) and risk-based evaluation of the standards. June 2005. Online. Available: www.beta.guild.org.au/research/project_displayasp?id=246 [accessed 3 November 2008]

5. Standard for the Uniform Scheduling of Drugs and Poisons. Online. Available: www.comlaw.gov.au/comlaw/Legislation/LegislativeInstrument1.nsf/0/5929B6B30E305E28CA257515001B5BDC?OpenDocument [accessed 4 March 2009]

6. NSW Government. The New South Wales poisons list. September 2008. Online. Available: www.health.nsw.gov.au/resources/publichealth/pharmaceutical/pdf/poisons_list.pdf [accessed 9 October 2008]

7. Pharmacists Board of Queensland. Publications — Board Bulletins. Online. Available: www.pharmacyboard.qld.gov.au/bulletins.htm?#2008 [accessed 30 May 2009]

8. Australian Medicines Handbook. Pseudoephedrine. AMH Adelaide; 2005. 377

9. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Statistics on drug use in Australia 2006. Canberra: AIHW; 2006. Online. Available: www.aihw.gov.au/publications/index.cfm/title/10393 accessed 3 November 2008]

10. Australian Self-Medication Industry. Pseudoephedrine ban not the answer to illicit drug problem. [media release]. ASMI Sydney 2007. Online. Available: www.asmi.com.au/documents/media-releases/Pseudo%2018%20Apr%2007.pdf [accessed 30 May 2009]

11. Pharmacy Guild of Australia. Project STOP. Online. Available: www.projectstop.com.au/ [accessed 3 November 2008]

12. Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Media talking points on pseudoephedrine: Channel 7 ‘Sunday Tonight’ program. Online. Available: www.psa.org.au/site.php?id=3259 [accessed 30 May 2009]