Chapter 8 Staged Interpolation Flaps

Interpolation flaps demand exquisite planning and execution. In return, their sophistication offers rich rewards with a highly vascularized covering that may resurface complex defects, provide tissue bulk, nourish free cartilage grafts, and restore lining or contour as needed. The terms axial, indirect, interpolation, and staged flaps are synonymous and all are variations of transposition repairs. All interpolation flaps have these shared features: (1) vascular pedicle based on a named artery and or its tributaries, (2) donor location distant and noncontiguous from the defect, and (3) two or more stages for completion (stage I for flap creation and closure, stage II for pedicle division, and often additional stages for revisions).

The success of these flaps is dependent on adhering to three key principles. First, all margins must be definitively cancer free. Second, these flaps should be considered as heavy surface coverings (skin, subcutis, muscle) and a stable infrastructure must exist to support them. A large nasal defect, for example, cannot simply be covered without stable cartilage support and mucosal lining. Third, optimal repairs often require the reconstruction of an entire subunit.1 Wounds that consume 50% or more of a subunit are best restored in total. All patients with staged flaps require extensive preoperative consultation. Multiple visits and revisions, temporary physical deformities, and intensive wound care, as well as substantial activity and work restrictions, are the rule in staged repairs. In exchange for this demanding regimen, however, are surgical results that have no equal. This chapter will discuss techniques for (1) paramedian forehead flap, (2) cheek-to-nose interpolation flap, and (3) Abbé or lip-switch flap as applied to skin cancer reconstruction.

PARAMEDIAN FOREHEAD FLAP (PFF), STAGE I

Indication

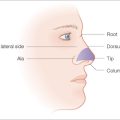

The paramedian forehead flap (PFF) is a workhorse in facial reconstruction. Although it may close any wound on the central face, its best application is to the distal nose (tip, ala, and columella) where tissue thickness and sebaceousness are closely matched by forehead skin.2 The PFF is ideal for recreating the convexity and projection of the nasal tip. Subtotal nasal tip and/or alar defects may be candidates for the PFF. Proximal wounds on the nasal dorsum, sidewall, nasal root, and medial canthus have inherently thinner skin and may be incongruous for the much thicker PFF unless a substantially deep defect is present.

Anatomy

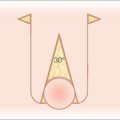

The primary and secondary vascular supply to the PFF is the supratrochlear (internal carotid system) and dorsal nasal artery (external carotid system), respectively. The supratrochlear artery (SA) is reliably located at the medial border of the eyebrow, 1.5–2 cm from the facial midline. At the medial eyebrow, a glabellar crease (if present) delineates where the SA crosses the superior orbital rim to enter the forehead (Figure 8.1). Below the orbital rim, the SA lies deep to the periorbital muscles (orbicularis oculi and frontalis). Above the rim, however, the SA pierces the frontalis muscle and ascends superficially into the forehead, sandwiched between the frontalis muscle below and the subcutis above. Consequently, to preserve the SA near the orbital rim, dissection must be below the frontalis muscle and deep fascia.

Flap Design

The ideal PFF is an aesthetic covering that restores normal contour and symmetry without creating a shapeless blob. Table 8.1 discusses the critical design issues in a PFF. The covering provided by a PFF requires a stable nasal infrastructure (cartilage support and mucosal lining). Structural cartilage grafts (SCG) to prevent nasal valve collapse and alar rim contraction are usual considerations in PFF repairs. More neglected, however, are SCG that restore contour to the nasal supratip. Contour grafts should be considered in patients that have thick nasal tip skin and supratip defects (Figure 8.2). Without a contour graft in these patients, a PFF alone may be insufficient to restore normal tip projection.3

TABLE 8.1 ISSUES IN PFF DESIGN FOR DISTAL NOSE DEFECT (NASAL TIP AND/OR ALA)

| DEFECT CONSIDERATIONS | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Does this defect require lining support? | Replacing lining may require intranasal mucosal flaps prior to PFF execution. |

| Does this defect need cartilage support? | Cartilage grafts may be replacement or structural in nature. Replacement grafts restore missing cartilage or bone. Structural grafts add to stability and contour, and prevent tissue contraction to an intact cartilage infrastructure. |

| Is the PFF sufficient to close this wound? | PFF may be combined with regional flaps, free cartilage grafts, and split- or full-thickness skin grafts for defects that extend onto multiple subunits. |

| Does the residual subunit need to be excised? | Cosmesis is often superior when entire subunits are resurfaced. |

| FLAP CONSIDERATIONS | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Has there been previous surgery at the proposed pedicle site? | Normal vascular anatomy may no longer be reliable and Doppler identification of a viable artery may be needed. |

| Does the flap template accurately account for the 3-dimensional contour of the nose and infratip? | A flexible template material (suture foil wrap, soft foam, Duoderm) is essential for accurately moulding the template design. Two-dimensional defect measurements are inadequate. |

| Does the forehead’s vertical height (from orbital rim to anterior frontal hairline) provide adequate length to reach the defect? | A short forehead height may require modifications to the template design and/or pedicle to optimize flap extension. |

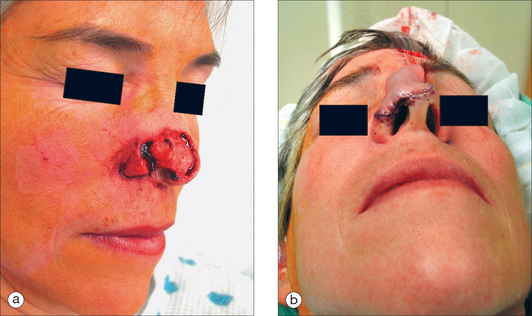

Measurements of the defect must be accurate, neither over- nor undersized for the wound. The PFF template should be measured after the residual subunit has been outlined, but prior to the excision of any remaining skin (Figure 8.3). This avoids an artificially enlarged dimension from a retracted wound edge. A template should also reflect the 3-dimensional nature of the nose, especially if a defect extends to the infratip, columella, and ala (Figure 8.4a). If the vestibular mucosa is missing, the PFF may be extended and turned down to provide nasal lining. The soft nasal triangle, however, is best approached with second intention as the PFF, even when skeletonized, will never match the thin, soft concavity in this area (Figure 8.4b). Whenever possible, the unaffected contralateral side should be used as a template to restore symmetry. A right-sided nasal tip and ala wound, for example, should be repaired based on the normal left tip and ala.

Figure 8.4 (a) Complex Mohs defect of the nasal tip, soft triangle, and medial ala, necessitating a 3-dimensional design. (b) Paramedian forehead flap designed to cover complex nasal tip and ala defect except for the nasal soft triangle, which is best recreated with second intention healing (see Figure 8.13b for long-term results).

The vertical height of the forehead (from orbital rim to anterior frontal hairline) will determine the potential reach of this flap, and may be estimated by using a suture. If the vertical length is inadequate (short forehead height relative to distal defect), then the modifications listed in Table 8.2 will significantly extend a flap’s distal reach.

TABLE 8.2 MODIFICATIONS TO THE PARAMEDIAN FOREHEAD FLAP FOR EXTENDED REACH

| FLAP DESIGN MODIFICATIONS | COMMENT |

|---|---|

| Vertical extension of flap into the anterior frontal scalp | Potential transfer of terminal hairs onto the nasal defect. |

| Potential disruption of frontal hairline and scarring alopecia if donor site closure is not complete. | |

| Extension of flap lateral to midline | Potential compromise of vascular supply to lateral flap extension. |

| Potential donor site morbidity with eyebrow elevation (scar contraction with second intention or distortion with complete closure). |

| PEDICLE MODIFICATIONS | COMMENT |

|---|---|

| Keeping width of pedicle at its base between 1.0–1.5 cm | Wider pedicles (> 1.5 cm) limit flap mobility. |

| Wider pedicles increase vascular strangulation during flap rotation toward the distal defect. | |

| Mobilizing base of pedicle below superior orbital rim | Requires subperiosteal elevation of entire medial brow complex off of the superior orbital rim and arcus marginalis. |

| May extend flap reach by at least 2 cm. | |

| Incorrect elevation and undermining may lead to periorbital trauma and compromise vascular pedicle (supratrochlear artery). | |

| Pedicle division at stage II will require eyebrow repositioning for bilateral symmetry. | |

| Relaxing incision at medial base of pedicle (toward glabella and nasal root) | Releases dermal attachments at the pedicle base that may enhance flap mobility. |

| Incision must not extend past superficial dermis. | |

| DEFECT MODIFICATIONS | COMMENT |

| Temporary alar suspension stitch | Suture is passed through the alar cartilages (if present) onto the glabella above. This suspends the nasal tip superiorly to meet the forehead flap, effectively extending flap reach. Suture is then removed at time of pedicle division. |

| Prominent suture reaction at the glabella is predictable. | |

| Potential for weakening the alar cartilage integrity with excessive superior suspension. |

Design considerations for the pedicle include its position and width. Identifying the SA pedicle may be done clinically, by using the anatomic landmarks mentioned earlier, or definitively by confirming with a manual Doppler (8–10 MHz frequency). The pedicle width, therefore, rarely needs to be greater than 1.5 cm.4 Wider pedicles in fact are counterproductive and restrict flap mobility as well as vascular integrity (by increasing torque and compression on the artery during flap rotation). This author routinely develops a pedicle base of 1.0 cm (Figure 8.3). Pedicle positioning should be contralateral to the predominant side of the wound to minimize pedicle twisting during movement. The right SA, for example, should be the PFF pedicle for a predominantly left-sided nasal defect.

Anesthesia

The PFF may be safely performed as an outpatient procedure. Tumescent anesthesia is useful by rapidly anesthetizing large areas with minimal patient discomfort. Local anesthesia (local infiltration and nerve blocks) may be supplemented by oral benzodiazepines (lorazepam, midazolam) and oral analgesics. Rarely, conscious sedation may be needed and are safely performed by dermasurgeons.5,6 Appropriate credentialing for advanced cardiac life support and sedation are essential for the latter modalities.

Execution

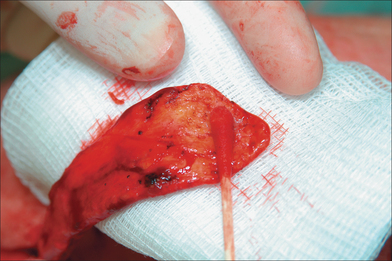

Cartilage and Lining Restoration

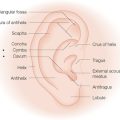

Cartilage grafts (CG) and nasal lining are essential ingredients for a stable nasal architecture. CG are either structural (native cartilage present but additional CG needed for support) (Figure 8.5) or restorative (replacing missing cartilage). Structural cartilage grafts serve to (1) support heavy flap tissue, (2) maintain airway patency of the internal nasal valve (priority in nasal reconstruction), (3) minimize scar contraction, and (4) restore contour projection (nasal tip). CG may be auricular (antihelix or concha; Figure 8.6), nasal (septum), or costal in nature. Auricular cartilage harvest is easiest and may be performed from an anterior or posterior approach. Anterior incisions are more accessible but scars are more visible than posterior incisions. Antihelical cartilage is excellent for long, straight segments whereas conchal cartilage is ideal for grafts that demand more curvature and substance.7,8 The subject of nasal lining is beyond the scope of this chapter. General options, however, for smaller mucosal defects (< 1 cm) include (1) turnover hinge flap, (2) turndown of a forehead flap extension, (3) full-thickness skin graft (FTSG), and (4) bipedicle vestibular skin advancement flap. Larger lining restoration may require (1) turnover forehead flap, (2) septal mucoperichondrial hinge flap, (3) composite septal chondromucosal pivotal flap, or (4) larger FTSG vascularized by an overlying PFF.9

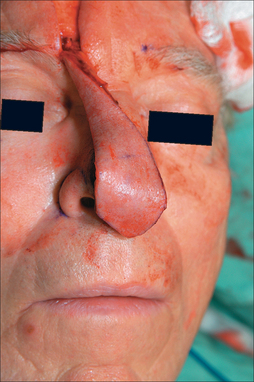

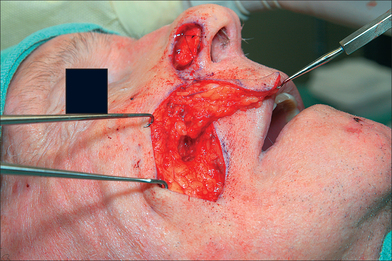

Flap Harvesting and Pedicle Mobilization

The PFF may be mobilized at its superior edge to include just the skin and subcutis or down to underlying galea. The former approach facilitates flap debulking during inset but results in greater bleeding. A subcutaneous level is preferred if the flap is in hair-bearing scalp to expose terminal hair bulbs for depilation. The level of undermining, however, delves deeper into the subgaleal plane as one approaches the eyebrow to preserve the SA. The transition from subcutis to subgalea should occur at least 3 cm above the orbital rim. Undermining past the orbital rim should be under direct visualization as the SA is at risk of transection. Occasionally, subperiosteal release of the arcus marginalis and brow complex is required to enhance flap extension (Table 8.2). The PFF should now overlie the defect without tension (Figure 8.7).

Flap Preparation and Inset

Prior to any suturing, the flap thickness must be revised to fit the defect. Aggressive debulking except for a thin subdermal layer is possible because of the excellent vascularity of the SA (Figure 8.8). Constant reference to the defect is mandatory to prevent excessive thinning. Flap inset begins with interrupted epidermal sutures to secure its leading edge with the defect. If dermal-buried sutures are placed, this author prefers Poliglecaprone 25 (Monocryl, Ethicon) because of its minimal tissue reaction, a desirable feature on the sebaceous nasal tip.10 Dermal sutures contribute to flap security and minimize incision line separation. The proximal flap as it abuts the nasal dorsum is not sutured until pedicle division.

Donor Site Closure

Donor areas are approximated as much as possible and any remaining wound heals by second intention (Figure 8.9). Patients may be reassured that this open portion will be significantly smaller because of inevitable wound contraction (Figure 8.10). Tissue expansion and complex scalp flaps should be avoided as they often lead to excessive morbidity on both donor and recipient tissue without cosmetic benefits. At most, unilateral or bilateral W-plasties along the frontal hairline may be considered for complete closure of the forehead wound. These W-plasties act as bilateral advancement and rotation flaps, with the W design to camouflage incision scars and preserve hairline continuity.4 Broad scalp paresthesia may be a price of donor site closure.

Postoperative Care

Postoperative bleeding at the sides of the exposed pedicle is common and may be prevented with meticulous electrocoagulation and a Surgicel or Surgicel Nu-Knit wrap of the exposed pedicle. This oxidized cellulose gauze promotes hemostasis and its removal causes less discomfort than Vaseline gauze.11 Visual fields are blocked with pressure dressings and the wearing of glasses is usually not possible without preoperatively customized devices.

PARAMEDIAN FOREHEAD FLAP, STAGE II

The second stage usually occurs approximately 3 weeks later and detaches the pedicle. Intermediate procedures may be needed (flap debulking and thinning) and should occur prior to the pedicle division. Stage II may be delayed for 4–6 weeks in patients at risk of flap compromise (heavy smokers) whereas earlier pedicle division (less than 3 weeks) may be safe but should not be performed routinely. In fact, the 6 weeks after stage I is a prime vascular period when revisions may be performed with impunity. Menick advocates a three-stage PFF during this 6-week vascular honeymoon. With this approach, stage I achieves flap inset without any distal flap thinning. Aggressive thinning of the flap occurs in stage II (3 weeks later) along with any revisions to cartilage grafts and lining. Pedicle division is then deferred until stage III (6 weeks from stage I).12 This three-stage approach does not affect flap survival and may permit more aggressive flap thinning and the usage of skin grafts for nasal lining. The three-stage approach is also useful for patients at high risk of flap necrosis, as thinning is delayed for an additional three weeks. This approach does, however, prolong the time a patient has with an unsightly pedicle in the central face.

The approach to the pedicle stump after division varies greatly. This author prefers to close the pedicle wound primarily and not in a V–Y inset. Cosmesis is often superior without the inverted V-shaped scar. Eyebrow repositioning is essential in all cases and may require a curvilinear ellipse for brow plasty (Figure 8.11).

Final

After pedicle division, additional revisions may be needed, such as dermabrasion (6–8 weeks from stage I), de-epilation, and contouring (Figure 8.12). After 8 weeks, however, further tuning should be deferred for several months to permit flap maturity and scar evolution. Early intervention for self-resolving issues only leads to unnecessary morbidity. A functional airway should always be evaluated prior to any intervention. The PFF is an extremely resilient and vascularized flap that has no equal in the aesthetic restoration of large complex nasal defects (Figures 8.13a,b and 8.14).

CHEEK-TO-NOSE INTERPOLATION FLAP (CNIF)

Indications

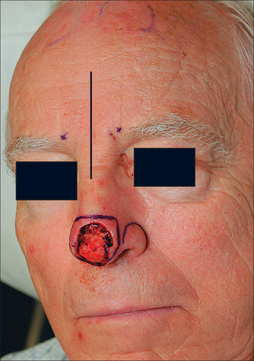

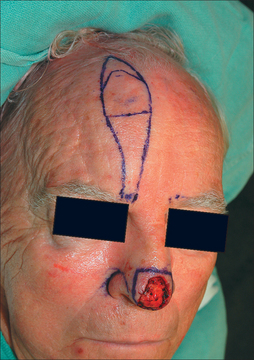

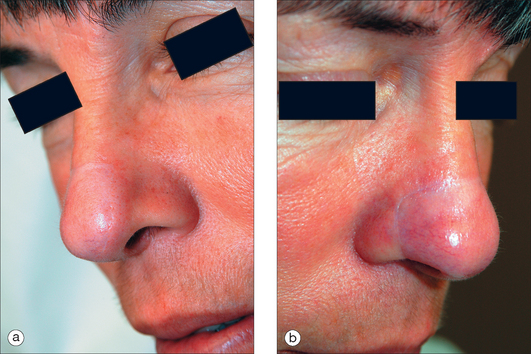

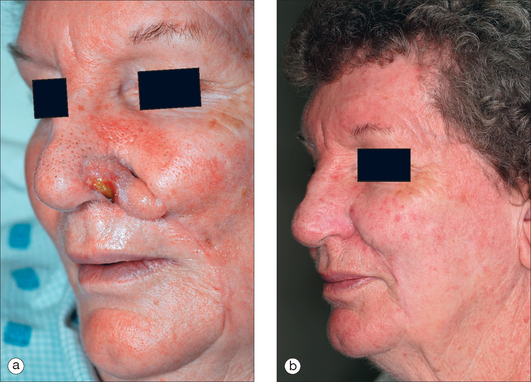

The CNIF is best at repairing small to medium-sized defects of the ala, infratip, and columella. The medial cheek donor skin is especially similar to the sebaceous texture of the ala. The CNIF is ideal for a deep defect (up to mucosa) that is confined to the ala and consumes 50% or more of this subunit (Figure 8.15). Although other closures may be considered for such wounds (melolabial transposition flap), the CNIF is advantageous in preserving the alar groove and concealing donor scar within the melolabial fold.13,14 Single-stage buried island pedicle flaps and subcutaneous hinge flaps are also viable alternatives for strictly alar defects.15,16 Wounds of the ala and cheek are not optimal for the CNIF alone and should be repaired in combination with other options (ie, cheek advancement flap).

Flap Design

Nasal infrastructure (cartilage and mucosal lining) requirements are stringent as with the PFF. A cartilage graft for the CNIF is structural and not restorative (as cartilage is absent from most of the fibrofatty ala). A CG braces the heavy CNIF and prevents alar retraction and adjacent nasal valve collapse (Figure 8.16). Further, it restricts the inevitable flap contraction to create a soft convex alar lobule rather than a bulbous prominence. In width, the CG should span up to the alar groove and in length, beyond the alar defect by 3–4 mm at each end. Its placement is close to the alar rim for support. CG attachment with nonabsorbable sutures is to the native cartilage medially and within an alar base pocket laterally. CG often requires thinning and sculpting to be 1 mm thin and rounded with beveled edges peripherally. Any CG must be secured prior to flap incision.

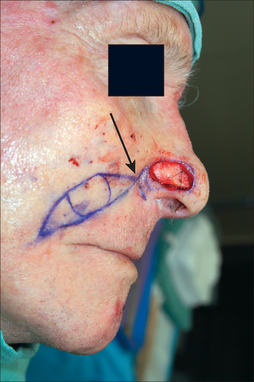

The entire alar lobule should be resurfaced when possible. The remaining ala up to the alar groove, except for a 1-mm margin of alar base and rim, will eventually be excised in stage II for full subunit repair. Flap design should include this enlargement. Some even advocate a flap template that is 1 mm larger in all dimensions, partially to counteract wound contraction and partially to exploit the trapdoor effect and recreate a lobular convexity.17 This mild oversizing may be achieved by incising on the outside edge of flap markings. Similar to the PFF, the contralateral normal side may serve as a model for template creation.

The template is now transferred to the medial cheek and lower melolabial fold and outlined, with the widest part of the flap positioned across or slightly above the oral commissure. Triangles are now drawn above and below the flap outline to create a curvilinear ellipse. The lower triangle will be excised full thickness to close the donor site. Proximally, the upper triangle must taper at least 0.5 cm below the lateral alar groove to avoid effacement of this landmark (Figure 8.16). Although this proximal triangle is drawn narrowly, the underlying pedicle is more wide and deep to maximize vascular supply. Flap reach should be confirmed with a stretched gauze that simulates actual movement. From the donor site, the flap transposes and rotates counterclockwise for a right-sided alar wound and clockwise for the left side. Template orientation must account for these directional distinctions.

Execution

The CNIF pedicle may be developed to be either myocutaneous or myosubcutaneous. The myocutaneous design includes skin, subcutis, and muscle fibers of the levator labii superioris alequae nasi (LLSAN). The myosubcutaneous pedicle excludes the overlying dermis and epidermis, which is excised at the time of flap harvest. Features of both designs are discussed in Table 8.3.

TABLE 8.3 PEDICLE VARIATIONS FOR THE CHEEK-TO-NOSE INTERPOLATION FLAP

| PEDICLE | FEATURES | COMMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Myocutaneous | Pedicle contains skin, subcutaneous fat, and muscular fibers from the levator labii superioris alequae nasi. | Easier to develop than myosubcutaneous design. |

| Proximal skin is narrow in width superficially but underlying pedicle is wider. | ||

| Overlying skin may restrict proximal flap movement unless relaxed with scoring incisions. | ||

| Myosubcutaneous | Pedicle is identical to above but is without the overlying proximal skin (epidermis and dermis). | The absence of overlying skin essentially creates a two-stage island pedicle flap. |

| Pedicle development is more challenging but movement is greater than with myocutaneous design. |

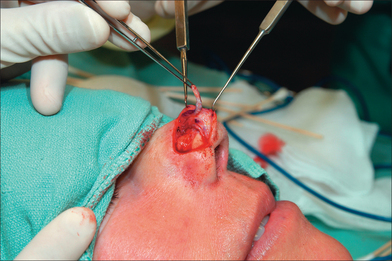

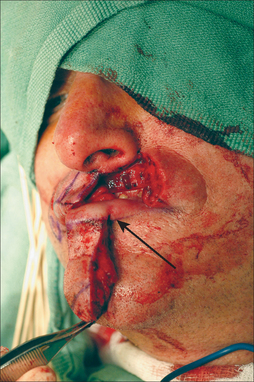

Superficial incisions indelibly score the flap outlines and prevent the inaccuracies of blurred pen markings. The lower triangle is then fully excised and the distal flap sharply elevated with a 3- to 4-mm subdermal fat layer. As one nears the proximal pedicle, dissection delves deeper to incorporate muscle fibers of the LLASN (Figure 8.17). Partial muscle inclusion is essential to preserving the arterial perforators for this flap. Hook retraction of the cheek laterally, the cutaneous lip medially, and the flap superiorly will expose these muscle fibers. Searching for the angular artery is contraindicated. Flap dissection is similar to that of an island pedicle flap in that excessive flap mobilization exacts the price of a smaller pedicle.

Resistance to flap movement may be alleviated by these maneuvers: (1) scoring incision (to dermis) at the proximal triangle (if a myocutaneous design was chosen), which frees proximal skin attachments tethering the flap, (2) closing the donor cheek in a superior oblique vector (northeast for the right cheek and northwest for the left), which progressively brings the flap medially and superiorly (Figure 8.18), and (3) temporary suspension suture lifting the flap to the upper cutaneous lip, which is removed in 1 week.

Once the flap reaches the defect with minimal tension, defect preparation begins with (1) peripheral undermining, (2) angulating rounded borders (theoretically reducing the trapdoor effect), and (3) debeveling all wound edges. The alar rim, however, should remain beveled and, likewise, the flap’s margin at the alar rim must be reverse-beveled to achieve a flush closure. The remaining alar subunit is not resected by this author until pedicle division.

CHEEK-TO-NOSE INTERPOLATION FLAP, STAGE II

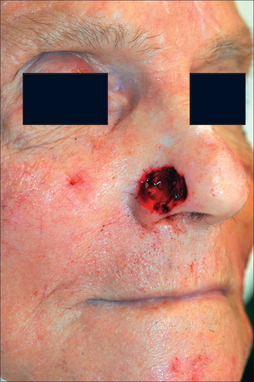

Pedicle division in stage II should not be attempted prior to 3 weeks. Given the more tenuous pedicle, intermediate stages are not wise and longer deferment of stage II is preferred for smokers. If the flap survives completely at Stage II, then the residual subunit may be excised except for 1–2 mm of the alar base, which serves to anchor the flap and maintain the lateral alar groove (Figure 8.19a,b). Subunit enlargement must be attentive to the recently placed CG.

The pedicle base may be divided and the cheek closed primarily (Figure 8.20). Alternatively, it may be partially inset as a V-shaped section into the cheek to restore bilateral symmetry. Re-inset is appropriate if either the donor cheek preoperatively was full or the flap was large. With a large flap, the donor cheek may appear flattened if the pedicle is not partially reset. However, resetting the pedicle does not address the lower melolabial fold, which is also flattened from flap harvest. This author finds the V-shaped inset incongruous and prefers to restore symmetry with an ellipse on the other side. This contralateral ellipse will restore both cheek and melolabial fold symmetry, as well as achieve a more youthful appearance. The maneuvers above, however, are rarely necessary, as patients are ultimately delighted with an aesthetically restored and cancer-free nose.

If necrosis is noted in stage II, then it is often seen at the distal flap margin and is usually due to a diminutive pedicle (Figure 8.21a). Gentle curettage will reveal the depth of necrosis (usually partial). Superficial necrosis is best approached with second intention healing and postponement of stage II. Deeper necrosis may be remedied with an excision of the failed margin and re-closure if possible, with the healthy proximal flap (Figure 8.21b).

Final

Issues that may require revisions following stage II typically target the following: (1) flap trapdooring (intralesional steroids, surgical debulking), (2) alar groove definition (incising and debulking underlying scar at sulcus), (3) alar thickness (excising a wedge of fibrous scar via an intranasal approach), and (4) airway patency.

The CNIF’s value as a staged repair lies in its tissue match with the lateral ala and distal nose. Donor scar is minimal and well camouflaged. The flap preserves important landmarks (alar groove) and meets high aesthetic standards (Figure 8.22). It is flexible in its reach and may even extend to resurface the floor of the nasal vestibule. Compared to the PFF, the CNIF differs by (1) repairing smaller, less complex nasal defects, (2) being better suited for repair of the lateral ala, (3) being less reliable in its vascularity, and (4) requiring less postoperative wound care and lifestyle restrictions.

ABBÉ (LIP-SWITCH) FLAP

Indications

A number of flaps are applicable for medium to large full-thickness lip defects. These include the Abbé, Estlander, Karapandzic, Gilles fan flap, and McGregor repairs. Among these options, the Abbé is best at restoring neuromuscular function with the least disruption to the perioral anatomy.18 Lip defects amenable for the Abbé are those that (1) are lateral to midline but do not involve the oral commissure (although wounds isolated to the philtrum are candidates), (2) consume ⅓ to ½ of the lip, and (3) involve significant loss of the orbicularis oris muscle. It is this last factor that demands functional muscle replacement, which is best provided by the Abbé procedure.

Anatomy

Nourishing the Abbé is the inferior labial artery (ILA), which branches off the facial artery and has a variable course across the lower cutaneous and mucosal lip. At midline, the ILA is always posteriorly located within the mucosal lip (red lip) at the level of the vermilion border. Here, it lies between the orbicularis muscle anteriorly and the mucosa posteriorly. Lateral to midline, the ILA location is less predictable. Within the lip, the ILA may be found either within the orbicularis oris muscle (minority) or between the muscle and mucosa (majority).19 The ILA is never located between the muscle and subcutis, a reassuring fact during flap creation.

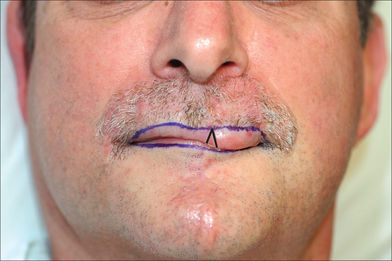

Flap Design

The Abbé template is best positioned at midline where arterial location is most predictable and donor site symmetry may be preserved. Paramedian locations may also be considered to match the vermilion border thickness between the donor and recipient lip. Extremely lateral flap designs, however, are contraindicated because of the potential distortion of the oral commissure. Donor site morbidity is low unless excessively resected, which may compromise stoma size.

Proper repair of the full-thickness defect in Figure 8.23 requires its enlargement to the upper cutaneous lip borders. The template fashioned may be less than the defect as the inherent stretch of lip tissue compensates for a smaller flap size. The nasal sill and alar crease must be preserved with any flap design and all landmarks (vermilion border, philtrum, etc) must be outlined prior to local anesthesia and incision (Figure 8.24).

Execution

Table 8.4 details the execution sequence for the Abbé repair, which may be safely performed as an ambulatory procedure.

TABLE 8.4 ABBÉ FLAP SEQUENCE FOR CLASSIC LIP-SWITCH (LOWER LIP FLAP TO UPPER LIP DEFECT)

| STEPS | COMMENT |

|---|---|

Inevitably, one side of the ILA must be transected to mobilize the Abbé flap. Which side to sacrifice is a critical decision. Generally, the ILA ipsilateral to the upper lip defect is preserved while the other side is incised (Figure 8.25). This permits the widest oral stoma possible for eating and minimizes pedicle twisting during closure. Unlike the forehead flap, in which the supratrochlear artery is never seen, the ILA side that is incised serves as an excellent reference point during dissection to preserve the contralateral pedicle. The pedicle stump should be approximately 1 cm, smaller in front but wider posteriorly. A healthy wide cuff of posterior mucosa is essential, and perhaps even more critical for pedicle survival than arterial preservation. There are even reports of complete flap survival based solely on a mucosal attachment (inadvertent transection of artery).20

Suction should be used frequently both for patient comfort and for visibility in this highly vascular location. What may be counterintuitive is the need to excise all remaining lip layers (any remaining skin, muscle, mucosa) at the defect to create room for the Abbé (Figure 8.25). Without clearing the defect, the incoming Abbé will not fit well and become blob-like in its appearance. Similarly, the flap must be harvested in its full thickness to preserve all neuromuscular structures. Also counterintuitive is the need to enlarge the defect for subunit repair when possible. Superior aesthetic results, however, may be achieved with subunit replacement.

Closure begins with the donor site first and suturing should approximate all lip layers in the following order: mucosa (absorbable gut), muscularis (polyglactin (Vicryl)), subcutis (Poliglecaprone (Monocryl)), then cutaneous. Mucosal sutures should be soft (silk or polyglactin) to avoid irritation. Horizontal mattress sutures are advocated by some to prevent any gaps in the posterior mucosa, which may lead to fistulas and leaks from the minor salivary glands. The donor incision line externally should be well everted (Figure 8.26). Especially critical is the accurate approximation of the vermilion– cutaneous border, which is facilitated by (1) scoring incisions marking the horizontal free margin (Table 8.4, Step 6) and (2) extending flap incision vertically on the pedicle side beyond the red lip border (Table 8.4, Step 8) (Figure 8.25). This latter maneuver liberates an edge of the vermilion border and permits the accurate realignment of this free margin with the defect. Flap inset also proceeds in the order as described earlier (mucosa to cutaneous). A buried suture to align the vermilion border may help to position the flap properly. The flap at the recipient site should lie flush with the surrounding skin.

ABBÉ FLAP, STAGE II

Pedicle division occurs in 3 weeks or may be deferred longer for flaps with questionable viability. An intermediate stage prior to pedicle division is not risky but is rarely needed. Prominent flap edema, especially at the mucosal border, is normal and will subside with time (8–12 weeks) as lymphatic and venous drainage becomes reestablished (Figure 8.27). Temptation to surgically intervene earlier should be resisted.

The vermilion–cutaneous borders should again be marked (Figure 8.27). Local anesthesia to infiltrate the pedicle and adjacent skin on both ends will suffice. Patients are asked to slightly open their lips, a Q-tip is placed behind the pedicle, and two hooks should retract the upper and lower lip apart for stability and traction.

The first step creates an inverted V-shaped incision that divides the pedicle (Figure 8.27). Following separation, the upper mucosal lip will have a triangular defect, which may be sutured side to side (Figure 8.28). The lower mucosal lip retains the triangular remnant of the pedicle, which may be either excised and discarded or resutured into the mucosal lip. Re-inset is appropriate if bulk is needed for donor site symmetry. As the mucosal lip heals exceptionally, the V-shaped inset blends well aesthetically, unlike that of its counterpart in the PFF and CNIF. If necessary, incisions may be carried into the recently sutured cutaneous lip on both ends for accurate tissue alignment.

Final

For male patients, any transferred hairs from the lower cutaneous lip and chin will continue to grow within the flap. The hair growth direction, however, will be reversed. Following stage II, revision surgery is rarely needed unless the vermilion border requires re-positioning. Flap edema will resolve with time (Figure 8.29). The time for neuromuscular recovery varies and can be age-dependent. Younger patients have almost full recovery within 6 months whereas older patients may require one year or more (Figure 8.30). The Abbé repair is extremely flexible in its applications. Two or more Abbé flaps may be harvested from the same donor lip, provided that overall oral patency is not compromised. Abbé patterns extending into the submental region have been described with some designs tunneling under an intact upper vermilion border.21,22 These modifications may resurface large and complex central-facial defects. The lip-switch flap may also be combined with other repairs for subtotal lip restoration.23

CONCLUSION

Complications with surgery

The cheek-to-nose interpolation flap in Figure 8.21a partially necrosed due to a shallow pedicle (minimal incorporation of muscle perforators at base). Fortunately, the necrotic area was small and superficial (gentle curettage of eschar). Pedicle division proceeded and the shallow wound healed secondarily. Dermabrasion followed (6 weeks from stage I) and final results are seen in Figure 8.21b. An alternative approach would have been to delay pedicle division for an additional 2 weeks to allow for a better assessment of second intention healing. This necrosis exemplifies the need to defer subunit enlargement until stage II and only if flap survival is assured. Had the subunit been excised at stage I and had flap necrosis been more extensive at stage II, then an unfortunate outcome would have turned disastrous.

1 Burget GC, Menick FJ. The subunit principle in nasal reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;76:239-247.

2 Sherris DA, Fuerstenberg J, Danahey D, Hilger PA. Reconstruction of the nasal columella. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2002;4:42-46.

3 Burget GC, Menick FG. The paramedian forehead flap. In: Burget GC, Menick FG, editors. Aesthetic nasal reconstruction. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 1994:57-91.

4 Quatela VC, Sherris DA, Rounds MF. Esthetic refinements in forehead flap nasal reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:1106-1113.

5 Otley CO, Nguyen TH. Safe and effective conscious sedation administered by dermatologic surgeons. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1333-1335.

6 Otley CO, Nguyen TH. Conscious sedation. In: Nouri K, Leal-Khouri S, editors. Techniques in dermatologic surgery. New York: Mosby; 2003:177-182.

7 Ratner D, Skouge JW. Surgical pearl: the use of free cartilage grafts in nasal alar reconstruction. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:622-624.

8 Byrd DR, Otley CC, Nguyen TH. Alar batten cartilage grafting in nasal reconstruction: functional and cosmetic results. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:833-836.

9 Baker SR. Internal lining. In: Baker SR, Naficy S, editors. Principles of nasal reconstruction. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 2002:31-46.

10 Molea G, Schonauer F, Bifulco G, D’Angelo D. Comparative study on biocompatibility and absorption times of three absorbable monofilament suture materials (Polydioxanone, Poliglecaprone 25, Glycomer 631). Br J Plast Surg. 2000;53:137-141.

11 Shinkwin CA, Beasley N, Simo R, Rushton L, Jones NS. Evaluation of Surgicel Nu-knit, Merocel and Vasolene gauze nasal packs: a randomized trial. Rhinology. 1996;34:41-43.

12 Menick FJ. A 10-year experience in nasal reconstruction with the three-stage forehead flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:1839-1855. discussion 1856–1861.

13 Fader DJ, Baker SR, Johnson TM. The staged cheek-to-nose interpolation flap for reconstruction of the nasal alar rim/lobule. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:614-619.

14 Baker SR, Johnson TM, Nelson BR. The importance of maintaining the alar-facial sulcus in nasal reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:617-622.

15 Hairston BR, Nguyen TH. Innovations in the island pedicle flap for cutaneous facial reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:378-385.

16 Johnson TM, Baker SR, Brown MD, Nelson BR. Utility of the subcutaneous hinge flap in nasal reconstruction. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:459-466.

17 Burget GC, Menick FG. The superiorly based nasolabial flap: Technical details. In: Burget GC, Menick FG, editors. Aesthetic Nasal Reconstruction. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 1994:93-115.

18 Burget GC, Menick FJ. Aesthetic restoration of one-half the upper lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;78:583-593.

19 Schulte DL, Sherris DA, Kasperbauer JL. The anatomical basis of the Abbé flap. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:383-386.

20 Millard DR, McLaughlin CA. Abbé flap on mucosal pedicle. Ann Plast Surg. 1979;3:544-548.

21 Kriet JD, Cupp CL, Sherris DA, Murakami CS. The extended Abbé flap. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:988-992.

22 Naficy S, Baker SR. The extended Abbé flap in reconstruction of complex midfacial defects. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2002;2:141-144.

23 Kroll SS. Staged sequential flap reconstruction for large lower lip defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;88:620-625. discussion 626–627.