Chapter 69 Stability Results After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

The primary purpose of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) is to restore knee stability. This chapter will provide meta-analytic data on hamstring, bone–patellar tendon–bone (BPTB), quadriceps tendon, and allograft stability. The stability data are measured by instrumented Lachman testing, usually but not exclusively KT-1000 (Medmetric, San Diego, CA). Pivot-shift data are not included because the high interobserver variability makes it impossible to quantify and it is an insensitive test in the nonanesthesitized patient.1 Although it is theoretically possible to have normal stability with instrumented Lachman testing and still have a pivot slide or even pivot shift present, this can only happen if the graft is put in a very vertical position. The data in this chapter are from the peer-reviewed literature, and the authors of these studies are all accomplished knee surgeons who are unlikely to place vertical grafts. Thus the data shown should be a good index to the relative stabilities of the knees tested.

Statistical Methods

Meta-analytic methods were used to compare the groups. Weighted means for normal and abnormal stability were generated as follows: For each treatment group, the proportion of individuals for an outcome event was determined by adding the number of events that occurred through all studies and dividing by the number of the patients in all the studies. The number of patients for any single-center, but not multi-center, study was capped at 100 to avoid disproportionate influence of any given study. In any study, if the number of patients for a given outcome was not recorded, the study was eliminated from the analysis of that outcome. For example, with one exception, if a study did not record the number of patients who have less than 2 mm of difference, then the study was not included in the <2 mm comparison.2–66

Results

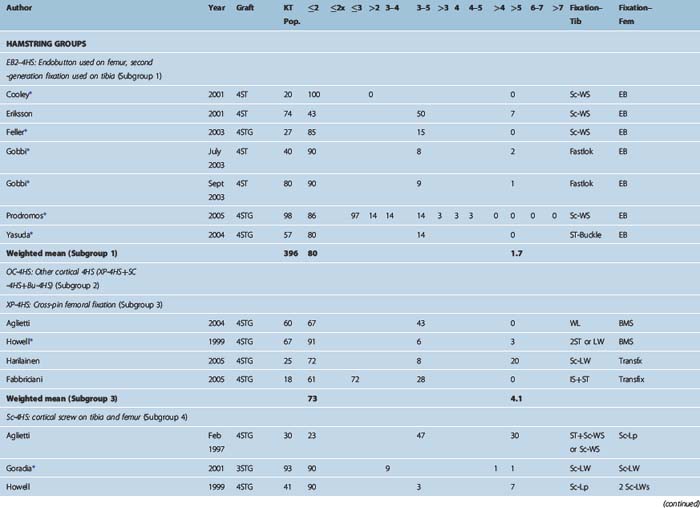

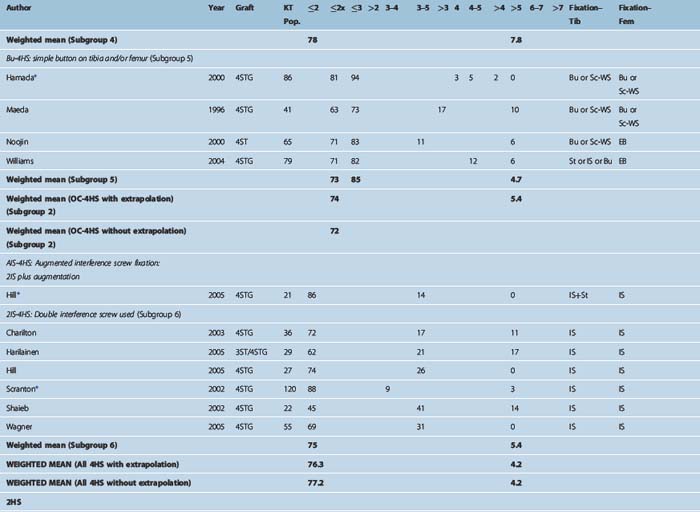

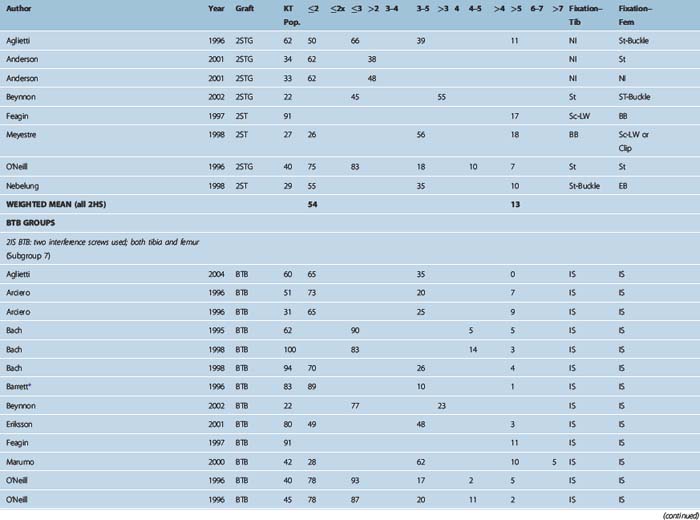

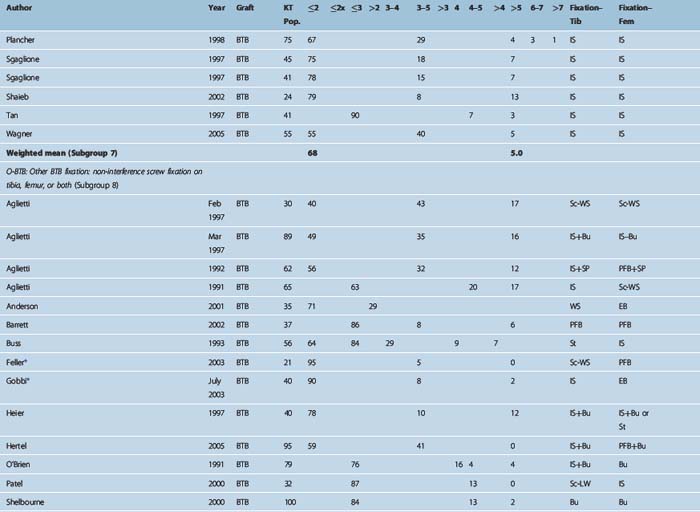

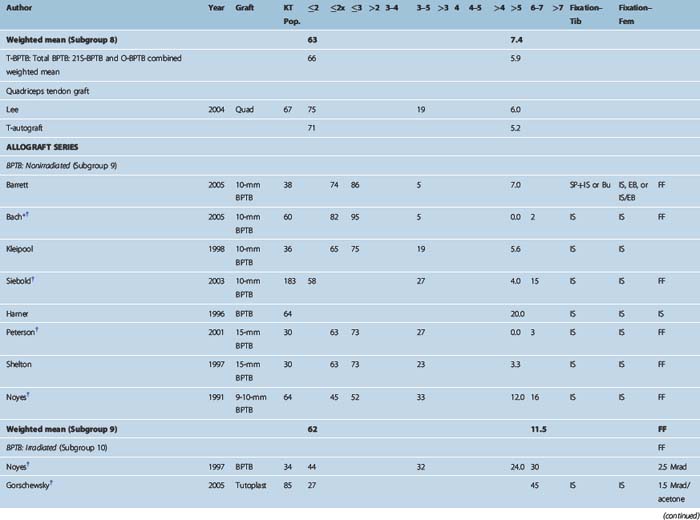

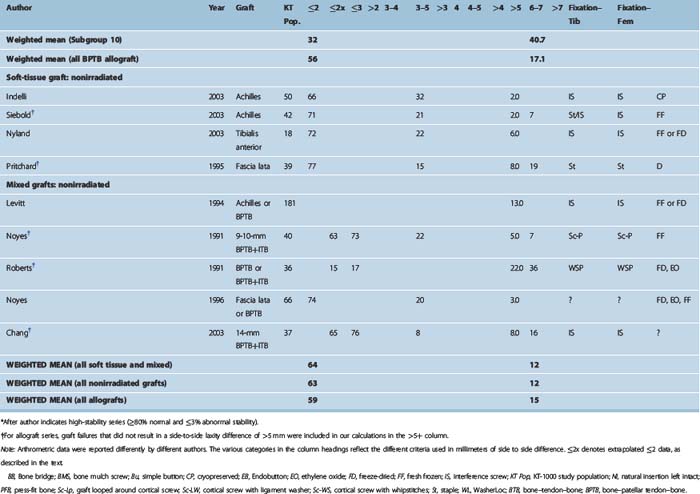

Table 69-1 shows all studies broken down by graft and then by fixation type for all graft types.

Only About Half of Reconstructed Knees Achieve Stability Symmetrical with the Other Knee

The goal of ACL surgery is to restore the preinjury level of stability, which should be the same as that of the other knee. True symmetry is achieved when the side-to-side difference (SSD) between the knees is 0. Measurement error increases this criterion to 1 mm. Thus we propose a SSD of 1 mm as defining knee stability symmetry. The IKDC “normal” criterion of up to a 2-mm difference may be satisfactory, but it is not truly normal. Indeed, a 2-mm SSD is what is commonly seen with partially torn ACLs.67 When the 1-mm criterion is applied, we see the following: For all autografts, about 30% have greater than 2-mm SSD.68 The remaining 70% fall into four categories: 2 mm, 1 mm, 0, or less than 0. If we assume that one-fourth of the 70% falls into each of these four categories, then it is reasonable to estimate that one-fourth of 70%, or 18%, are exactly 2 mm different. Adding this 18% (exactly 2 mm) to the 30% (greater than 2 mm) would mean that 48% of the reconstructed population has a 2-mm or greater SSD. This leaves about 52% with 1 mm or less SSD (i.e., true symmetry with the other knee). Thus roughly one-half of the autograft ACLRs, in the hands of the experienced knee surgeons who are the authors of these studies, have stability that is either equivalent to a partially torn ACL or worse. The allograft data68 show significantly lower stability rates (see Table 69-1).

Table 69-1 presents the raw data for stability from all the studies. The principal areas of interest are the “normal” and “abnormal” stability columns. Abnormal stability in most cases is equivalent to graft failure. The primary table subdivision is by graft type. These are four-strand hamstring (4HS) autograft, two-strand hamstring (2HS) autograft, BPTB autograft, and quadriceps tendon autograft and allograft. The secondary subdivision is by graft subgroup and by fixation type. Subdividing by fixation groups is possible to do with the autografts because of the large number of studies. It is only possible with the allografts to break out a BPTB/interference subgroup because of the smaller number of studies.

Stability Rates by Graft Type

The principal findings were as follows:

Stability Rate by Graft Fixation Subgroups

Stability rates for these subgroups are as follows:

Aperture Versus Nonaperture Fixation

For soft tissue grafts, there was no stability advantage for aperture fixation. Indeed, as just described, the 4HS-EB2 group, which had entirely nonaperture cortical fixation, had the highest stability rates of any graft fixation subgroup. Thus the so-called “bungee effect” would appear to be nonexistent. This is not surprising, as studies have shown that fixation on rigid cortical bone enhances stiffness much more than the greater length of the construct diminishes it.69 Also, variations in fixation stiffness are eliminated once the graft heals into the bone tunnel because the fixation is no longer load bearing. What really matters is how much the graft may elongate during this healing period from either slippage or plastic deformation. Neither of these is related to fixation stiffness.

Four-Strand Hamstring Versus Bone–Patellar Tendon–Bone Stability Rates

Because BPTB has long been considered the “gold standard” for ACLR. it may be surprising to some that 4HS was found to have higher stability rates. However, as the 4HS graft is a significantly stronger graft (see Chapter 10), the excellent 4HS stability rates do make sense if modern fixation is used. Prior analyses have seemed to show that hamstring grafts had lower stability rates than BPTB.70,71 However, these studies commingled the much-lower-stability 2HS studies with the higher-stability 4HS studies. If the 2HS studies are removed, it turns out that there was no stability advantage to BPTB in those studies by comparison with 4HS. Also, many of the highest-stability 4HS series were published after those studies. They were thus not included in those analyses but contribute significantly to the higher 4HS stability rates found here.

Allograft Versus Autograft

Allograft use has been steadily increasing. Surgeons who wish to avoid the morbidity of BPTB as well as the harvest of hamstrings are among the many who have been turning increasingly to allografts. The data presented here show significantly lower stability rates for allografts, with an abnormal stability rate, which usually represents graft failure, about three times higher than for autografts. These low-stability results also would indicate that ligamentization may indeed proceed differently for allogeneic tissue. This may be due in part to the less-effective and slower rate of recellularization that occurs with allografts.72 There is anecdotal evidence that late failure rates may be higher for allografts,73,74 which may be related to this same phenomenon.

Many now believe that some form of sterilization is necessary for allografts over and above sterile processing (see Chapter 70). Although higher levels of radiation have been believed to provide good sterilization, they have also long been considered to decrease graft strength. However, the radiated grafts in this study had lower stability rates than the nonirradiated grafts, even though the radiation levels in these studies were below 3 MRADs.49,63 This level is below that required to kill the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)75 but is still apparently high enough to diminish graft strength. Some have felt the answer lies in radioprotectant that allows virucidal 5 MRAD level sterilization while potentially avoiding graft weakening.76 Clinical studies to test this hypothesis are ongoing.

A variety of chemical treatments of allografts are also variably carried out by different tissue banks.77,78 It is unknown how these treatments affect graft ligamentization, cellular repopulation, and ultimate strength. Careful clinical follow-up will be required to assess which allograft treatments are optimal regarding both sterility and stability.

Conclusions

1 Kim SJ, Kim HK. Reliability of the anterior drawer test, the pivot shift test, and the Lachman test. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;317:237-242.

2 Anderson A, Snyder R, Lipscomb B. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective randomized study of three surgical methods. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:272-279.

3 Beynnon B, Johnson R, Fleming B, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament replacement: comparison of bone-patellar tendon-bone grafts with two-strand hamstring grafts. J Bone Joint Surg. 2002;84A:1503-1513.

4 Feagin JA, Wills RP, Lambert KL, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: bone-patella tendon-bone versus semitendinosus anatomic reconstruction. Clin Orthop. 1997;341:69-72.

5 Meyestre J, Vallotton J, Benvenuti J. Double semitendinosus anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: 10-year results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1998;6:76-81.

6 O’Neill D. Arthroscopically assisted reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: a follow-up report. J Bone Joint Surg. 2001;83A:1329-1332.

7 Shelbourne DK, Gray T. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with autogenous patellar tendon graft followed by accelerated rehabilitation: a two- to nine-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:786-795.

8 Gobbi A, Mahajan S, Zanazzo M, et al. Patellar tendon versus quadrupled bone-semitendinosus anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective clinical investigation in athletes. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:592-601.

9 Aglietti P, Zaccherotti G, Buzzi R, et al. A comparison between patellar tendon and doubled semitendinosus/gracilis tendon for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a minimum five-year follow-up. J Sports Traumatol Relat Res. 1997;19:57-68.

10 Aglietti P, Buzzi R, Giron F, et al. Arthroscopic-assisted anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with the central third patellar tendon. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1997;5:138-144.

11 Arciero RA, Scoville CR, Snyder RJ, et al. Single versus two-incision arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 1996;12:462-469.

12 Bach BR, Jones GT, Hager CA, et al. Arthrometric results of arthroscopically assisted anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using autograft patellar tendon substitution. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:179-185.

13 Bach BR, Tradonsky S, Bojchuk J, et al. Arthroscopically assisted anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using autograft patellar tendon autograft: five- to nine-year follow-up evaluation. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:20-29.

14 Bach BR, Levy ME, Bojchuk J, et al. Single-incision endoscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using patellar tendon autograft: minimum two-year follow-up evaluation. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:30-40.

15 Buss DD, Warren RF, Wickiewicz TL, et al. Arthroscopically assisted reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament with use of autogenous patellar-ligament grafts: results after twenty-four to forty-two months. J Bone Joint Surg. 1993;75A:1346-1355.

16 Eriksson K, Anderberg P, Hamberg P, et al. A comparison of quadruple semitendinosus and patellar tendon grafts in reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg. 2001;83B:348-354.

17 Hertel P, Behrend H, Cierpinski T, et al. ACL reconstruction using bone-patellar tendon-bone press-fit fixation: 10-year clinical results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2005;13:248-255.

18 Heier KA, Mack DR, Moseley JB, et al. An analysis of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in middle-aged patients. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:527-532.

19 O’Brien SJ, Warren RF, Pavlov H, et al. Reconstruction of the chronically insufficient anterior cruciate ligament with the central third of the patellar ligament. J Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73A:278-286.

20 Patel JV, Church JS, Hall AJ. Central third bone-patellar tendon-bone anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a 5-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:67-70.

21 Plancher KD, Steadman JR, Briggs KK, et al. Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament in patients who are at least forty years old: a long-term follow-up and outcome study. J Bone Joint Surg. 1998;80A:184-197.

22 Sgaglione NA, Schwartz RE. Arthroscopically assisted reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: initial clinical experience and minimal 2-year follow-up comparing endoscopic transtibial and two-incision techniques. Arthroscopy. 1997;13:156-165.

23 Shelbourne KD, Urch SE. Results of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction based on meniscus and articular cartilage status at the time of surgery: five- to fifteen-year evaluations. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:446-452.

24 Tan MY, Yeo SJ, Tay BK. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using patellar tendon autografts: a review of results. Singapore Med J. 1997;38:529-534.

25 Barrett GR, Noojin FK, Hartzog CW, et al. Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament in females: a comparison of hamstring versus patellar tendon autograft. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:46-54.

26 Shaieb MD, Kan DM, Chang SK, et al. A prospective randomized comparison of patellar tendon versus semitendinosus and gracilis tendon autografts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:214-220.

27 Aglietti P, Giron F, Buzzi R, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: bone-patellar tendon-bone compared with double semitendinosus and gracilis tendon grafts. J Bone Joint Surg. 2004;86A:2143-2155.

28 Aglietti P, Buzzi R, D’Andria S, et al. Arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patellar tendon. Arthroscopy. 1992;8:510-516.

29 Marumo K, Kumagee Y, Tanaka T, et al. Long-term results of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using semitendinosus and gracilis tendons with Kennedy ligament augmentation device compared with patellar tendon autografts. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2000;10:251-265.

30 Barrett GR, Treacy SH. The effect of intraoperative isometric measurement on the outcome of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a clinical analysis. Arthroscopy. 2000;12:645-651.

31 Aglietti P, Buzzi R, D’Andria S, et al. Reconstruction of the chronically lax anterior cruciate ligament using the middle third of the patellar tendon: a 3–9 year follow-up. Ital J Orthop Traumatol. 1991;17:479-490.

32 Cooley VJ, Deffner KT, Rosenberg TD. Quadrupled semitendinosus anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: 5-year results in patients without meniscus loss. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:795-800.

33 Feller JA, Webster KE. A randomized comparison of patellar tendon and hamstring tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:564-573.

34 Yasuda K, Kondo E, Ichiyama H, et al. Anatomic reconstruction of the anteromedial and posterolateral bundles of the anterior cruciate ligament using hamstring tendon grafts. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:1015-1025.

35 Gobbi A, Tuy B, Mahajan S, et al. Quadrupled bone-semitendinosus anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a clinical investigation in a group of athletes. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:691-699.

36 Prodromos CC, Han YS, Keller BL, et al. Stability results of hamstring anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction at two- to eight-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:138-146.

37 Williams RJIII, Hyman J, Petrigliano F, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with a four-strand hamstring tendon autograft. J Bone Joint Surg. 2004;86A:225-232.

38 Maeda A, Shino K, Horibe S, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with multistranded autogenous semitendinosus tendon. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:504-509.

39 Howell SM, Deutsch ML. Comparison of endoscopic and two-incision techniques for reconstructing a torn anterior cruciate ligament using hamstring tendons. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:594-606.

40 Scranton P, Bagenstose JE, Lantz BA, et al. Quadruple hamstring anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a multicenter study. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:715-724.

41 Hill PF, Russell VJ, Salmon LJ, et al. The influence of supplementary tibial fixation on laxity measurements after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstring tendons in female patients. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:94-101.

42 Nebelung W, Becker R, Merkel M, et al. Bone tunnel enlargement after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with semitendinosus tendon using Endobutton fixation on the femoral side. Arthroscopy. 1998;14:810-815.

43 Noojin FK, Barrett GR, Hartzog CW, et al. Clinical comparison of intraarticular anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using autogenous semitendinosus and gracilis tendons in men versus women. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:783-789.

44 Charlton WP, Randolph DAJr, Lemos S, et al. Clinical outcome of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with quadrupled hamstring tendon graft and bioabsorbable interference screw fixation. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:518-521.

45 Fabbriciani C, Milano G, Mulas PD, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with doubled semitendinosus and gracilis tendon graft in rugby players. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2005;13:2-7.

46 Harilainen A, Sandelin J, Jansson KA. Cross-pin femoral fixation versus metal interference screw fixation in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstring tendons: results of a controlled prospective randomized study with 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:25-33.

47 Goradia VK, Grana WA. A comparison of outcomes at 2 to 6 years after acute and chronic anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions using hamstring tendon grafts. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:383-392.

48 Hamada M, Shino K, Horibe S, et al. Preoperative anterior knee laxity did not influence postoperative stability restored by anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:477-482.

49 Gorschewsky O, Klakow A, Riechert K, et al. Clinical comparison of the Tutoplasty allograft and autologous patellar tendon (bone-patellar tendon-bone) for the reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: 2- and 6-year results. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1202-1209.

50 Roberts TS, Drez DJr, McCarthy W, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using freeze-dried, ethylene oxide-sterilized, bone-patellar tendon-bone allografts: two year results in thirty-six patients. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:35-41.

51 Pritchard JC, Drez DJr, Moss M, et al. Long-term followup of anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions using freeze-dried fascia lata allografts. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:593-596.

52 Kleipool AEB, Zijl JAC, Willems WJ. Arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with bone-patellar tendon-bone allograft or autograft: a prospective study with an average follow up of 4 years. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1998;6:224-230.

53 Shelton WR, Papendick L, Dukes AD. Autograft versus allograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 1997;13:446-449.

54 Siebold R, Buelow JU, Bos L, et al. Primary ACL reconstruction with fresh-frozen patellar versus Achilles tendon allografts. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2003;123:180-185.

55 Bach BRJr, Aadalen KJ, Dennis MG, et al. Primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using fresh-frozen, nonirradiated patellar tendon allograft: minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:284-292.

56 Barrett G, Stokes D, White M. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in patients older than 40 years: allograft versus autograft patellar tendon. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1505-1512.

57 Chang SKY, Egami DK, Shaieb MD, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: allograft versus autograft. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:453-462.

58 Harner CD, Olson E, Irrgang JJ, et al. Allograft versus autograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: 3- to 5-year outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;324:134-144.

59 Indelli PF, Dillingham MF, Fanton GS, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using cryopreserved allografts. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;420:268-275.

60 Levitt RL, Malinin T, Posada A, et al. Reconstruction of anterior cruciate ligaments with bone-patellar tendon-bone and Achilles tendon allografts. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;303:67-78.

61 Noyes FR, Barber SD. The effect of an extra-articular procedure on allograft reconstructions for chronic ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73A:882-892.

62 Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD. Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament with human allograft: comparison of early and later results. J Bone Joint Surg. 1996;78A:524-537.

63 Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD. Arthroscopic-assisted allograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in patients with symptomatic arthrosis. Arthroscopy. 1997;13:24-32.

64 Nyland J, Caborn DNM, Rothbauer J, et al. Two-year outcomes following ACL reconstruction with allograft tibialis anterior tendons: a retrospective study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2003;11:212-218.

65 Peterson RK, Shelton WR, Bomboy AL. Allograft versus autograft patellar tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a 5-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:9-13.

66 Aglietti P, Buzzi R, Menchetti P, et al. Arthroscopically assisted semitendinosus and gracilis tendon graft in reconstruction for acute anterior cruciate ligament injuries in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:726-731.

67 Rijke AM, Perrin DH, Goitz HT, et al. Instrumented arthrometry for diagnosing partial versus complete anterior cruciate ligament tears. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:294-298.

68 Prodromos CC, Joyce BT, Shi K, et al. A meta-analysis of stability after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction as a function of hamstring versus patellar-tendon graft and fixation type. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:1202-1208.

69 To JT, Howell SM, Hull ML. Contributions of femoral fixation methods to the stiffness of anterior cruciate ligament replacements at implantation. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:379-387.

70 Yunes M, Richmond JC, Engels EA, et al. Patellar versus hamstring tendons in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a meta-analysis. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:248-257.

71 Freedman K, D’Amato M, Nedeff D, et al. Arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a metaanalysis comparing patellar tendon and hamstring tendon autografts. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:2-11.

72 Scheffler S, Unterhauser F, Keil J, et al. Comparison of tendon-to-bone healing after soft tissue autograft and allograft ACL reconstruction in a sheep model. Presented at the 2006 meeting of the European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery, and Arthroscopy, Innsbruck, Australia. May, 2006.

73 Prodromos CC, Fu F, Howell S, et al. Controversies in soft tissue anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Presented at symposium at the 2006 of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Chicago. March, 2006.

74 Siegel MG. Personal communication. May 2006.

75 Fideler BM, Vangsness CTJr, Moore T, et al. Effects of gamma irradiation on the human immunodeficiency virus. J Bone Joint Surg. 1994;76A:1032-1035.

76 Forng RY, Willkommen H, Almeida J, et al. Terminal sterilization of human tissue allografts: application of high-dose gamma irradiation using the clearant process. Unpublished data, Year

77 Mroz TE, Lin EL, Summit MC, et al. Biomechanical analysis of allograft bone treated with a novel sterilization process. Spine J. 2006;6:34-39.

78 Caborn D, Nyland J, Chang HC, et al. Tendon allograft cryoprotectant incubation and rehydration time alters mechanical stiffness properties. Presented at the 2006 meeting of the European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery, and Arthroscopy, Innsbruck, Australia. May, 2006.