25 Sports Medicine

This chapter provides a brief overview of several of the more common sports-related injuries.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Pediatric athletes are anatomically and physiologically different from their adult counterparts. Developing bone is structurally weaker than adult bone. The physis, or growth plate, is between the metaphysis and epiphysis in the long bones of children. It is weaker than adjacent ligaments and thus more prone to fracture under high energy transfer. Physeal fractures are unique to children and account for 15% to 20% of all pediatric fractures (see Chapter 22).

Injuries by Body System

Shoulder Injuries

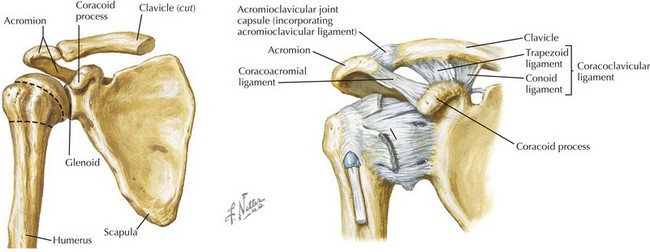

The shoulder girdle is composed of three joints: the sternoclavicular joint, acromioclavicular (AC) joint, and glenohumeral joint. The shoulder is the loosest joint in the body, with a shallow glenoid fossa and little bony support (Figure 25-1). Both acute traumatic and chronic overuse injuries are common.

Acromioclavicular Separation

The AC joint is composed of the acromion of the scapula and the distal clavicle. The AC and coracoclavicular ligaments stabilize the joint (see Figure 25-1). AC joint injuries, including sprains, subluxations and dislocations, are referred to as shoulder separations and account for 10% of all shoulder injuries. Injury to the AC joint is usually caused by a fall onto the top of the shoulder, causing the scapula and acromion to be pushed inferiorly, and the clavicle, with its medial end attached to the sternum, to be elevated. AC separations have a 5 : 1 male-to-female ratio and are encountered most frequently in hockey, wrestling, and the martial arts. Examination reveals asymmetric enlargement of the AC joint with localized tenderness to the joint. Forward flexion, extension, and cross-chest adduction results in AC joint pain. Diagnosis is made clinically or by plain radiographs dedicated to the AC joint. Milder separations are typically treated nonoperatively with rehabilitation, and the far less common severe separations may require surgical repair.

Anterior Shoulder Dislocation

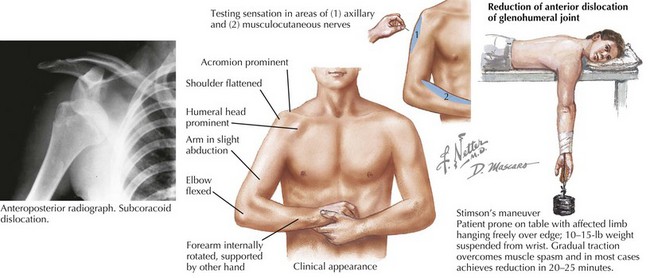

Examination reveals flattening of the deltoid prominence, prominence of the acromion, fullness of the subcoracoid region, and downward displacement of the axillary fold (Figure 25-2). It is also important to test for axillary and musculocutaneous nerve injury (see Figure 25-2).

Evaluation requires axillary, anteroposterior (AP), and scapular Y radiographs both before and after reduction to rule out associated fracture. An acute glenohumeral joint dislocation is an orthopedic emergency and requires closed reduction. There are many techniques for closed reduction; two of the more common are the traction–countertraction technique and Stimson’s maneuver (see Figure 25-2). It is important to reexamine the neurovascular integrity of the arm after reduction. Surgical reduction is rarely indicated. After reduction, the arm is immobilized for 2 to 4 weeks followed by gradual rehabilitation. Up to 90% of patients with shoulder dislocations before age 20 years have a recurrence.

Elbow Injuries

Elbow Dislocation

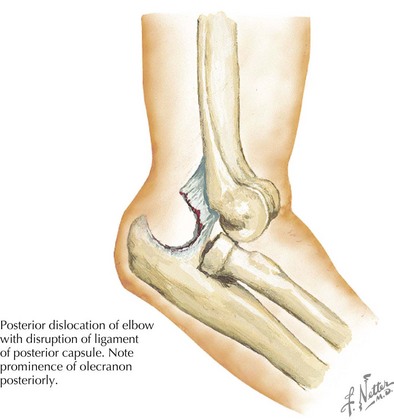

The elbow is the most commonly dislocated joint in children. Posterior dislocations are more common because of the shape of the olecranon process. They occur in older children, whose physes have closed, after falling backward onto an outstretched hand with the shoulder abducted. Simple dislocations can be seen in conjunction with associated fractures. On examination, an obvious deformity is noted, with the olecranon process displaced prominently behind the distal humerus (Figure 25-3). A careful neurovascular examination must be performed before and after reduction, paying particular attention to the median nerve. AP and lateral radiographs are useful in diagnosis. Isolated dislocation is treated by closed reduction. Unlike a shoulder dislocation, the greatest risk for an elbow dislocation is stiffness rather than recurrence. For this reason, immobilization is required for a short period of time, and return to full use is closely supervised.

Hip Injuries

Avulsion Fractures

Avulsion fractures occur because of a sudden contraction of a muscle pulling on a developing apophysis and are commonly seen in sports such as soccer, ice hockey, gymnastics, and sprinting. The combination of intensive training at an inherently weak epiphyseal plate predisposes an athlete to an avulsion fracture. Athletes often describe a pop after a forceful kick followed by sudden pain. The most common sites of pelvic avulsion injuries are the anterior inferior iliac spine and the ischial tuberosity caused by the powerful contraction of the sartorius and rectus femoris muscles, respectively. Although commonly seen in the hip, developing athletes can sustain avulsion fractures at other sites as well (see the Elbow Injuries section above). Plain radiographs of the pelvis should be carefully examined when avulsion fractures are suspected, since they can often be quite subtle radiographically.

Knee Injuries

Patellar Dislocation

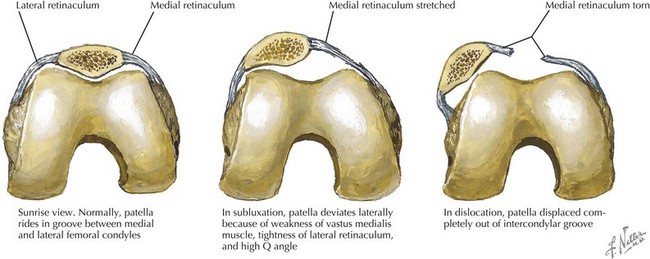

Patellar dislocations occur when the quadriceps contract to extend the knee but the patella is not in the intercondylar groove and gets displaced laterally. These dislocations typically occur in sports such as dance and gymnastics that involve a lot of jumping, twisting, and pivoting. This dislocation occurs more commonly in girls. Patients present with the knee flexed in intense pain and may describe a popping sensation (Figure 25-4). The examination reveals effusion, limited range of motion, the inability to bear weight, and a laterally displaced patella. Reduction should be performed promptly. With the patient supine with the hips flexed, the knee should be gently extended while medial pressure is applied to the dislocated patella. The practitioner performing the reduction will typically feel the patella return to the tibiofemoral tract. After reduction, radiographs should be taken to rule out a concomitant fracture, and the knee should be immobilized. Patellar subluxation may be observed if the history is consistent with dislocation but the pain has improved and the examination results are normal. Patellar dislocations commonly recur, with up to 15% of pediatric patients having a second event.

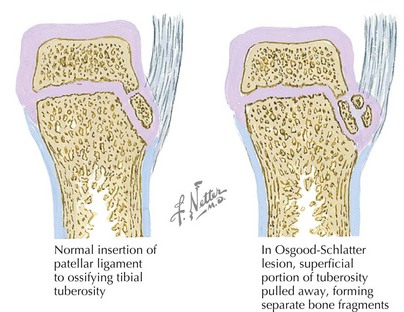

Osgood-Schlatter Disease

Osgood-Schlatter disease, the most common overuse injury of the adolescent knee, occurs at the anterior tibial tubercle. Athletes involved in sports that involve substantial cutting, running, and jumping are at risk, and they typically present with pain, swelling, and prominence of the tibial tubercle (Figure 25-5). On physical examination, tenderness at the tibial tubercle can be elicited. Radiographs are not necessary to make this clinical diagnosis, but when obtained, they can demonstrate soft tissue swelling over the tibial tubercle or fragmentation of the tubercle. Osgood-Schlatter disease is typically a self-limited disease and usually resolves with closure of the tibial growth plate. Treatment involves symptomatic control with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and may involve limitation of activity until improvement of the pain and limp. Stretching of the quadriceps and hamstrings as well as physical therapy to strengthen the quadriceps can be helpful.

Soft Tissue Injuries

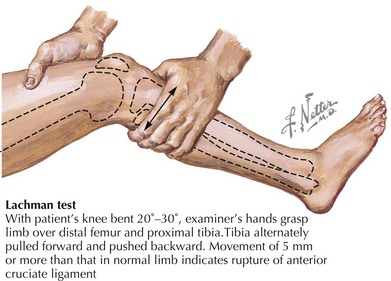

Medial collateral ligament or lateral collateral ligament injuries are rare when the epiphysis is open because the involved ligaments are stronger than the growth plate. When present, swelling may be minimal, but tenderness will be present over the involved ligament. The knee should be tested for laxity with varus and valgus testing, as shown in Figure 25-6. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries involve rotational forces on a fixed foot. The patient will report a “pop” and rapid swelling with decreased range of motion. The Lachman test (Figure 25-7) is a method of detecting this injury. Arthroscopy or MRI is often needed for definitive diagnosis.

Brenner JS. Overuse injuries, overtraining, and burnout in child and adolescent athletes. Pediatrics. 2007;119(6):1242-1245.

Demorest RA, Bernhardt DT, Best TM, Landry GL. Pediatric residency education: is sports medicine getting its fair share? Pediatrics. 2005;115(1):28-33.

Holly BJ, Hang BT. Common acute upper extremity injuries in sports. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2007;8(1):15-31.

2000 Intensive training and sports specialization in the young athlete. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1 Pt 1):154-157.

Sciascia A, Kibler WB. The pediatric overhead athlete: what is the real problem? Clin J Sports Med. 2006;16(6):471-477.