Chapter 15 Sports Medicine

Participation in athletics is both an enjoyable pastime and a part of keeping physically and mentally fit. Some individuals may only be interested in general conditioning and weight loss (Table 15-1). Others may want specific exercises for certain events. Regardless of the activity, risks are always involved, and today’s physician must be able to not only treat the various injuries that arise but also offer counsel on a wide range of other interrelated subjects, such as technique, training, and injury prevention. If the participants are children, other responsibilities are necessary. The physician should help make certain that realistic goals are set and that the activity is enjoyed by those who take part in it. Parents and coaches should be reminded that success is measured not necessarily just by winning but by the enjoyment and the amount of effort put forth. Whenever team sports are involved, all members should be allowed to play, and attempts should be made to match size and physical maturity as closely as possible. Children should learn how to play the various games as well as how to follow their rules. They should be properly supervised and should not be encouraged to play with pain. The role of the coach should be to instruct and supervise and not to give medical treatment or advice. Treating athletes is also somewhat different than treating other patients in that many of them, whether young or adult, are unwilling to simply give up playing when injuries arise. Many of them may accept a more physically tolerable substitute activity, however.

Table 15-1 Calories Expended in Common Activities*

| Activity | Calories per Hour |

|---|---|

| Light housework | 120 |

| Walking | 250–300 |

| Golf | 300 |

| Singles tennis | 480 |

| Bicycling | 450–500 |

| Jogging | 600 |

| Swimming | 650–700 |

* To be effective, an exercise should be performed three to five times per week for at least 30 to 60 minutes each time.

Prevention of Injuries

CONDITIONING

Proper conditioning means the development of strength, endurance, cardiovascular fitness, power, and flexibility. It also includes the development of proper body mechanics, form, and agility. The exact skill training depends on the specific sport involved, but lower extremity injuries can generally be lessened by strengthening exercises for individuals with loose joints to protect against ligament damage and stretching exercises for individuals with tight joints to avoid muscular strains. Staying in shape during the off-season may involve running stairs and jogging in place at home.

WARMING UP

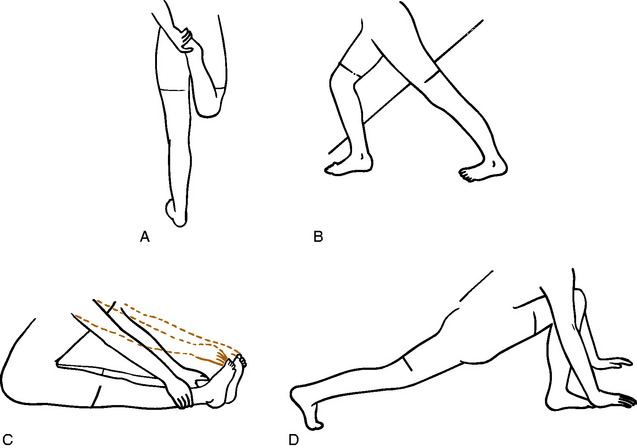

Beginning any activity gradually reduces the incidence of injury, especially injury to the muscle–tendon unit. Stretching is especially important to avoid strain. Flexibility is often diminished after a long period of inactivity, and stretching is particularly important when resuming a sport. The heel cord, hamstrings, and quadriceps should have special attention (Fig. 15-1). Tissue stretches better when warm. Therefore, stretching is best performed after slow jogging or walking for 5 minutes. Two types of stretching exercises may be performed. Static stretching is a slow, gradual stretching through full movement and holding at the position of maximum stretch for 10 to 20 seconds before relaxing. A pulling sensation, not pain, should be felt. Ballistic stretching, which involves rapid, repetitive movements, is also occasionally used but is generally less effective and may even cause minor muscular tears. It is usually not recommended.

Injuries to Muscles

MUSCULAR TEARS

Pain that develops acutely from violent activity is usually the result of a muscle tear. This may be partial or complete and may even involve the fascia. Muscles that cross two joints, such as the hamstrings, seem to be the most vulnerable. The diagnosis is usually not difficult, although it may not be easy to differentiate complete from incomplete ruptures. Sudden onset of pain, swelling, and marked local tenderness are characteristic. Pain is increased by stretching the affected muscle unit. Complete rupture may reveal a palpable defect on examination, but swelling often makes it difficult to diagnose a complete tear.

CONTUSIONS

Muscular bruises are common in all athletic events, even in the so-called noncontact sports. They are differentiated from ruptures and strains because function remains after the injury, and the contusion usually results from direct trauma. The thigh and upper portion of the arm are most commonly involved. The diagnosis is usually not difficult. Tenderness is present at the site of injury, and there is usually ecchymosis, although it may not appear until later. Treatment is directed at avoiding the complications of myositis ossificans and contractures and returning the athlete to full, pain-free competitive activity. This is accomplished by the rapid application of ice to the affected area to control bleeding and the removal of the athlete from further competition. Crutches may be necessary for the lower extremity injury, and complete bed rest with elevation of the extremity may even be indicated to control swelling and pain. A compression wrapping is helpful in early stages. After 24 to 48 hours, gentle isometric muscle contractions may be started, and active gentle range of motion is gradually added at the patient’s tolerance. Passive range of motion should be avoided. Any increase in pain or swelling is an indication to resume complete rest and application of ice. Full strength and complete flexibility are gradually restored by exercise. Reinjury is avoided by allowing complete healing to occur before returning to activities and by appropriately protecting the injured site. A return to athletics should follow only complete recovery.

MYOSITIS OSSIFICANS (OSSIFYING HEMATOMA)

The roentgenographic diagnosis can usually be made 2 to 4 weeks after the contusion. Plain radiographs are usually sufficient. The initial appearance is that of a poorly defined opaque mass in the soft tissue adjacent to the bone (Fig. 15-2). As the mass matures, it becomes more clearly outlined and dense. The lesion usually stabilizes in 3 to 6 months and begins to resorb slowly, often without any disability. Eventually, it transforms itself into mature bone and is partially resorbed. Radiographic maturity is usually reached in about 6 months.

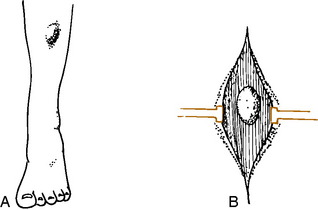

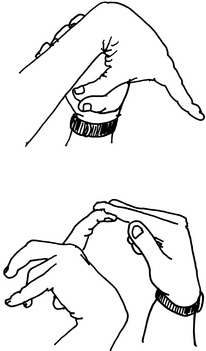

FASCIAL HERNIAS

These hernias often develop as a result of a simple contusion or small puncture wound that causes a rent to develop in the fascia and aponeurosis that envelops all muscle. Often, however, there is no history of trauma. The defect may vary in size, the smallest being 1 cm. Hernias may also develop in weak fascial areas in patients with chronic compartmental syndromes as a result of increased pressure in the compartment. They are also seen where nerves emerge from the fascia. Examination will reveal a palpable “tumor” mass, especially when the muscle is relaxed (Fig. 15-3). Muscle contraction may cause the mass to disappear, and direct pressure also “reduces” the mass. There may be numbness in the foot if the hernia protrudes through a neural foramen.

Injuries to Runners

BIOMECHANICS

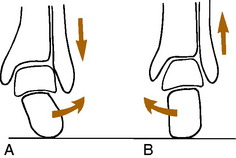

The running gait pattern is a repetitive movement that consists of a support phase, when the foot is on the ground, and a nonsupport phase. It is during the support phase that most injuries develop. Distance runners usually begin this phase by landing on the heel (sprinters usually land on the forefoot). As weight is taken on the heel, the calcaneus will begin to roll laterally (pronate, evert) under the talus at the subtalar joint (Fig. 15-4). This allows the heel to absorb shock and adapt to the underlying surface. The forefoot follows this motion by pronating, and at the same time, the tibia begins to rotate internally in proportion to the amount of heel pronation. As the weight moves forward, the calcaneus begins to supinate (invert) or roll back medially under the talus, and the tibia begins to externally rotate. This allows the foot to become more rigid and gives the heel cord a strong lever on which to act and transfer power. There are also a number of other coordinated motions that occur in the pelvis, hip, and other joints throughout the gait cycle, but understanding the subtalar joint mechanics is the most important.

EXAMINATION

In the supine position, the true leg lengths are measured between the anterior superior iliac spines and the medial malleoli. Discrepancies of 0.5 to 1.0 cm may be significant in the runner and require correction by a shoe lift. The range of motion of the hips is then determined. Internal and external rotation should be within 30 degrees of each other. Marked external rotation may cause an out-toed gait. The knee is closely examined, especially if patellar pain is present, and the Q angle is determined (Fig. 15-5). Patients with high Q angles may develop knee pain with running. The range of motion of the ankle is then determined with the knee extended. Fifteen degrees of dorsiflexion is normal. Any tightness of the heel cord is noted.

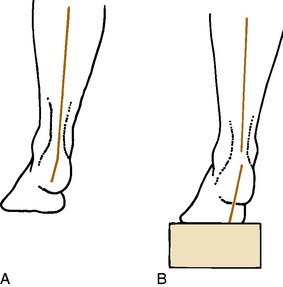

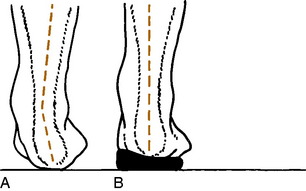

The patient then kneels on the examining table, and leg–heel and heel–forefoot alignments are determined. First, the neutral position of the subtalar joint is found by everting and inverting the foot and finding the point where the head of the talus is placed in the navicular and is no longer palpable (Fig. 15-6). This may require a little practice and is often only a rough estimate. Next, leg–heel alignment is determined by drawing lines posteriorly that bisect the lower portion of the leg and calcaneus (Fig. 15-7). The lines should be parallel or have no more than 2 to 3 degrees of varus. Heel–forefoot alignment is estimated by observing the relationship of the calcaneal line to the plane of the metatarsal heads. Normally, these lines should be perpendicular.

BACK, HIP, AND THIGH PAIN

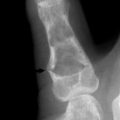

Stress fractures occasionally occur in the pelvis and femur of the distance runner (Fig. 15-8). They should be ruled out in all cases of chronic pain that fail to respond to routine symptomatic management. The appropriate roentgenographic study should include a bone scan if the diagnosis is uncertain. As with other stress fractures, reduction of activity is usually curative, but fractures of the femoral neck may require internal fixation.

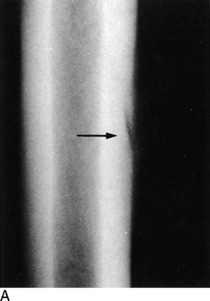

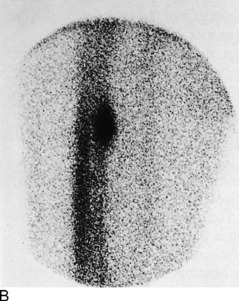

Fig. 15-8 Stress fracture of the femur (arrow). A, Plain anteroposterior (AP) roentgenogram. B, Bone scan.

Hamstring strains are a less common cause of disability in the distance runner than in the sprinter. They are treated as previously described. Stretching exercises are important not only because they can prevent local injuries but also because tight hamstrings may cause excessive lumbar lordosis that adds strain to the back when running. Rather than strain the hamstring, the sprinter whose apophyses are not closed may occasionally avulse the ischial tuberosity instead. If there is delay in assessment, the avulsed fragment may enlarge as it heals, causing a palpable fullness on clinical examination and bony enlargement on radiographic evaluation (Fig. 15-9). Unless the injury is acute and the athlete is highly competitive, treatment is symptomatic only. The fragment usually shrinks over time, but some of it may persist indefinitely.

KNEE PAIN

OVERUSE SYNDROMES

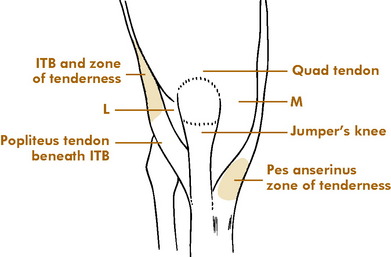

Major injuries of the meniscus or ligaments are uncommon in the knees of runners. More frequent are overuse disorders that develop because of the repetitive nature of running (Fig. 15-10). Several areas are commonly affected:

ANTERIOR KNEE PAIN SYNDROME (PATELLOFEMORAL PAIN SYNDROME)

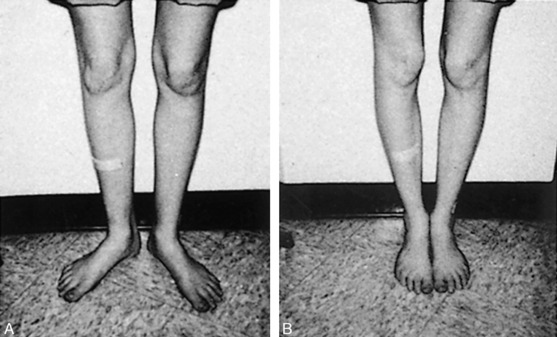

This is a condition in which pain develops beneath or, more commonly, around the patella (see Chapter 11). It is sometimes seen in conjunction with varying amounts of fibrillation and degeneration of its articular cartilage (chondromalacia), although the relationship of this to symptoms has not been established. The diagnosis is usually one of exclusion (e.g., meniscus injury, jumper’s knee). Anything that adversely affects the normal “tracking” of the patella in its femoral groove may lead to pain, often on the lateral side. The causes are frequently multifactorial: (1) an increased Q angle with a bowstringing effect; (2) tightness of the lateral retinaculum with relative weakness of the vastus medialis muscle; (3) patellofemoral malalignment, sometimes with subluxation; (4) direct trauma; (5) simple overuse; and (6) malalignment of the extremity (Fig. 15-11).

The wide variety of treatments used to manage this condition attests to the difficulty in curing it. Conservative measures such as rest, anti-inflammatory medication, local heat, stretching exercises, quadriceps exercises in extension, and avoiding the offending activity are useful. Many patients benefit from a referral to a physical therapist. Patellar straps or braces seem to be of only limited benefit. Although arthroscopically shaving the fibrillated articular cartilage has been a common surgical intervention, the results are often inconsistent, probably because the changes in the articular cartilage are not the source of pain. If a distal malalignment problem is present, an orthotic device in the shoe may occasionally be advised to help correct the tracking problem, mainly on empiric grounds. As a last resort, a surgical procedure to realign the patella sometimes eliminates the symptoms, but it would seem difficult to justify such a major operation simply to allow continued running. Despite the frustrating nature of the condition, however, most patients do well with a home exercise program.

LOWER LEGPAIN

MEDIAL TIBIAL STRESS SYNDROME

A common cause of leg pain is what is sometimes referred to as the shin splint, or medial tibial stress syndrome. This is a specific overuse syndrome involving the origin of the soleus muscle and causing pain along the deep midthird of the medial border of the tibia (Fig. 15-12). The flexor digitorum longus may also be involved. The disorder is most likely caused by a bone stress reaction. Many causative factors have been suggested, although excessive pronation of the foot is often present. The disorder often develops in poorly conditioned athletes or runners who run on hard surfaces. There is usually tenderness to palpation along the posteromedial border of the midtibia. The roentgenogram may show some late periosteal reaction or cortical thickening in this area. Bone scanning or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may help in the diagnosis.

COMPARTMENTSYNDROMES

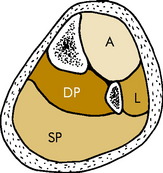

Vigorous exercise may lead to swelling and mild ischemia in any of the four natural compartments in the calf (Fig. 15-13). The anterior and deep posterior compartments are the most commonly affected in runners, and the condition is usually chronic or recurrent rather than acute when it develops in runners. The disorder develops either from local arterial spasm or swelling that increases the pressure in the unyielding compartment. This compromises the local blood flow and leads to muscle ischemia and pain. Permanent muscle and nerve damage may result, but this is rare in the common chronic type seen in runners. More frequently, the only symptom is cramping pain during exercise that is often relieved by rest and recurs when activities are resumed after rest. Physical findings are minimal, but tenderness may be present in the affected compartment, as well as slight weakness of the involved muscles. Mild paresthesias are occasionally noted. Confirmation of the diagnosis may require measurement of intracompartmental pressures.

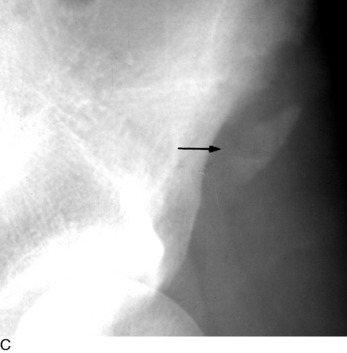

STRESS FRACTURES

Stress fractures are common injuries of the lower leg and must always be ruled out in the evaluation of pain. They usually develop in response to a sudden increase in the stress applied to a weight-bearing bone. Thus, they are more likely to occur in the novice who is just beginning running or in the individual who suddenly increases mileage. Any weight-bearing bone may be affected. The proximal medial tibial border and the lower portion of the fibula are the most commonly affected areas in the lower part of the leg. The only physical findings are local tenderness and edema. The roentgenograms are usually negative initially and begin to show healing changes in 2 to 4 weeks (Fig. 15-14). The bone scan is often more sensitive to early changes.

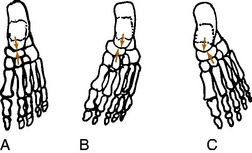

ANKLE AND FOOT PAIN

Several overuse syndromes may affect the ankle and foot. Most involve the musculotendinous unit. They are all treated in a similar manner: by rest (or modification of activities), anti-inflammatory medication, and local heat. An occasional local steroid injection may also be helpful, but the Achilles tendon should not be injected. Rupture of this tendon is always a concern, and it is possible that this event may be hastened by local injections. Stress fractures also occur in the foot, and the most common areas of involvement are the metatarsals, navicular, or calcaneus (Fig. 15-15). They are treated by protection. Activities are resumed as tolerated.

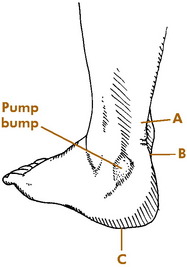

THE PUMP BUMP

This is a painful thickening that develops over the lateral attachment of the Achilles tendon (Fig. 15-16). It is usually the result of friction and irritation from a poorly padded heel counter. Conservative measures including proper shoes are usually curative. The back of the shoe may have to be cut out for a period of time. A heel lift may also be helpful. In resistant cases, the small bump may be removed surgically.

BLISTERS

Blisters are common in runners and are best treated by the following preventive means:

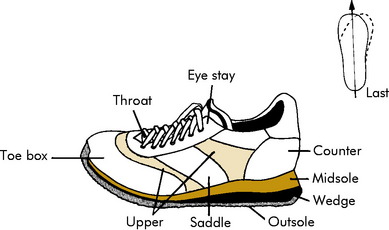

RUNNING SHOES

A properly constructed shoe is an absolute necessity for the runner (Fig. 15-17). The running shoe functions mainly to protect the foot from the environment and prevent overpronation. When purchasing a new shoe, the same socks should be worn that will be used when running. There is no perfect shoe, but a good shoe should have the following:

ORTHOTICS

Orthotics may be soft, semirigid, or hard; several materials can be used. Semiflexible devices seem to be preferred by most runners. Simple supports are available in sporting goods stores and are usually made from rubber. Other soft orthotics can be made from materials that are heated and applied to the individ-ual’s foot while the heel is held in a neutral position (Fig. 15-18). “Posts” may be added for additional support. Custom-fabricated, rigid orthotics can also be made from plaster molds of the feet by laboratories that specialize in their preparation.

TREATMENT SUMMARY

The general care of runners involves accurate diagnosis, evaluation for alignment problems, and assessment for training errors. It has been found that the majority of injuries are related to training errors and that excessive mileage accounts for many of these. In addition to excessive mileage, other causes of training problems are running on improper surfaces or terrain and abrupt increases in the intensity of runner’s routine. Therefore, minor modifications in the runner’s schedule may be helpful. However, complete rest is occasionally the only acceptable treatment, and a rest of 4 to 6 weeks is often necessary to allow for complete recovery. The following recommendations are often helpful:

Running, Walking, and Arthritis

Injuries to the Upper Extremity

THE SHOULDER

DISORDERS OF THE ROTATOR CUFF

The overarm throwing motion may rank second only to running as the most common factor in athletic events. The range of motion of the shoulder is the greatest of all joints and is made possible by the relatively minimal amount of bony contact between the humeral head and the glenoid. Thus, stability is sacrificed for flexibility, and this places a great burden on the capsule and rotator cuff musculature for joint stability. As a result, the soft tissue may develop overuse injuries because of repetitive strains placed on it during exercise. These strains may lead to overuse changes ranging from simple tendinitis (tendinopathy) to rotator cuff rupture. Tissue calcification may even occur. Swelling of the rotator cuff and subacromial bursa then develops, which narrows the space between the head of the humerus and the overlying acromion and coracoacromial ligament. An abnormally shaped (hooked) acromion may contribute to the problem. This may lead to the development of crepitus and impingement when the shoulder is abducted. Abduction further narrows the subacromial space and can result in a painful catching sensation; thus, the term impingement syndrome (see Chapter 5). Clinically, shoulder pain is present during and after use. The pain may radiate down the deltoid muscle because of the common innervation of the deltoid and supraspinatus muscle. Crepitus is common, and there is tenderness to palpation over the rotator cuff, usually the supraspinatus tendon.

The treatment of rotator cuff tendinitis is usually conservative. Rest and avoiding the offending activity are most important. Push-ups should be avoided. Local steroid injections may relieve pain but should be used cautiously in athletes. Repetitive injections should certainly be avoided (especially in the young), and vigorous use of the shoulder after injections should not be allowed. Rest, stretching and strengthening exercises, and proper throwing or swimming mechanics should be stressed. Referral is indicated in resistant cases.

INJURIES TO THE ACROMIOCLAVICULAR JOINT

More common is acromioclavicular separation or dislocation (see Chapter 5). The lesion is often graded 1 through 5. A grade 1 injury is simply a minor strain of the acromioclavicular ligaments. A grade 2 injury involves rupture of the acromioclavicular ligaments but preservation of the coracoclavicular ligaments. In grade 3, 4, and 5 injuries, there is complete rupture of all supports with upward displacement of the clavicle. (Grade 4 and 5 injuries are rare.)

DISLOCATION OF THE GLENOHUMERAL JOINT

Most shoulder dislocations are anterior in direction and result from trauma (see Chapter 5). The usual cause is a fall on the outstretched arm. The diagnosis is suspected when there is an absence of the normal fullness beneath the deltoid. If the dislocation is anterior, the humeral head is palpable anteriorly, the arm is held externally rotated, and internal rotation is painful. Posterior dislocations characteristically have pain on external rotation, the arm is held in internal rotation, and there is flatness of the anterior shoulder contour. Both types often become recurrent. The treatment is reduction, and this should be accomplished as soon as reasonable. Roentgenograms should always be taken before reduction to rule out other bony injury. Epiphyseal fracture of the upper portion of the humerus should especially be ruled out.

THE ELBOW

EPICONDYLITIS

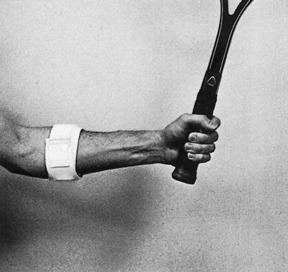

Inflammation or degeneration of the tendinous origin of the forearm muscles at the epicondyles is a common disorder (see Chapter 6). The extensor origin (tennis elbow) on the lateral aspect is more commonly involved than the flexor side (golfer’s elbow). The disorder is not restricted to tennis players, but may be caused by any activity that involves repeated forceful gripping. Tennis players who use both hands for backhand strokes do not develop this condition as often as those who use the one-handed grip. Whether or not epicondylitis is truly inflammatory is under investigation. Chronic disorders of this type may begin as a traumatic or inflammatory event, but the underlying pathology is often more degenerative (tendinosis). Physical examination reveals point tenderness over the affected epicondyle, typically about 1 cm distal to the bony epicondyle. Provocative maneuvers are often positive with the pain aggravated by gripping against resistance.

Treatment consists of rest, anti-inflammatory medication, local heat, ice, or ultrasound and local steroid injections. A tennis-elbow brace may help relieve the strain, and a gradual, progressive, controlled stretching and strengthening exercise program for the forearm and hand muscles may be helpful (Fig. 15-19). Tennis players can prevent recurrences by using proper techniques. The handle of the tennis racquet should be the proper size, and the ball should be struck in the center of the racquet face. The body rather than the arm should be used for power. In addition, a good ball should always be used, and there should be less tension on the strings for the average player. Oversized racquets seem to help by providing a larger “sweet spot.”

LITTLE LEAGUE ELBOW

The symptoms may be of acute or gradual onset. When the onset is sudden, the symptoms are usually secondary to an avulsion injury of either the lateral or the medial epicondyle (Fig. 15-20). More commonly, the process is chronic, and the symptoms are usually those of persistent discomfort and stiffness that are aggravated by use of the extremity.

Fig. 15-20 Avulsion of the medial epicondyle in association with a throwing injury in an adolescent.

Prevention is the key. To protect the elbow of the immature player from developing these disorders, most authorities believe that the number of pitches and the innings pitched should be monitored. In addition, at least 3 to 4 days of rest should be allowed between pitching. (Games and practices all count.) If enough irritation and swelling are present that a flexion contracture of 20 to 30 degrees exists, the adolescent should not be allowed to pitch again until normal motion has returned. Young pitchers should never “pitch through” their pain. Permanent growth disturbances and arthritis could be the end result.

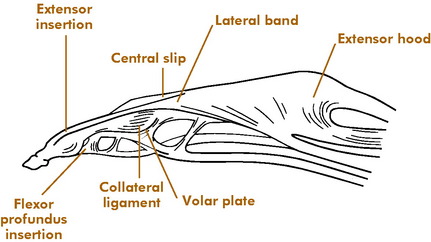

THE HAND

The anatomy of the hand and finger is complex, and injuries to the bones and soft tissues are common in sports (Fig. 15-21). The joint may simply be referred to as “jammed,” and the injury is therefore frequently not fully appreciated or properly treated. Permanent loss of function may be the end result.

MALLET FINGER (BASEBALL FINGER)

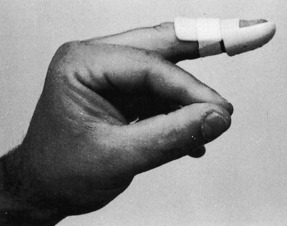

Avulsion of the insertion of the extensor tendon at the base of the distal phalanx is a common injury. It occurs secondary to sudden forceful flexion of the distal phalanx, often from a blow to the tip of the extended finger. A fragment of bone may be avulsed along with the tendon. Active extension of the distal phalanx is lost. Tenderness and swelling are noted on the dorsum of the distal interphalangeal joint, and the distal phalanx rests in the position of moderate flexion. Long-standing cases occasionally develop a mild hyperextension deformity of the proximal interphalangeal joint (Fig. 15-22). This contributes to what is called the swan-neck deformity. Roentgenographic examination may reveal an avulsion fracture of the distal phalanx.

If no fracture is present or if the fracture is small, the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint is immobilized in slight hyperextension for 5 weeks (Fig. 15-23). Vigilance is the key. The splint should not be removed by the patient until the treatment is complete. If the fracture fragment is large (more than 25% of the joint surface) and displaced, the joint should be tested for stability (Fig. 15-24). If the joint is stable, the same treatment is recommended; that is, treatment used in hyperextension. If the joint is unstable or the fragment is quite large, surgical repair may be necessary. Some residual lack of extension may persist regardless of treatment, but the functional result is usually excellent. Patients should be warned that the tender dorsal swelling and redness may last for 2 to 3 months.

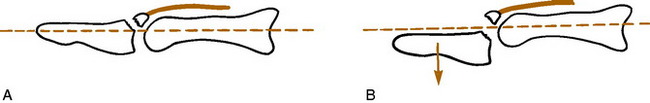

FLEXOR DIGITORUM PROFUNDUS AVULSION (JERSEY FINGER)

The deep flexor may be avulsed from its attachment by sudden DIP hyperextension. The ring finger is most often involved. The injury commonly occurs in football when a tackler grabs the jersey of the opponent who pulls away. The tendon eventually retracts proximally into its sheath (Fig. 15-25). If bone is avulsed, it may be evident, but otherwise, roentgenograms are not revealing. Clinically, the volar aspect of the DIP joint is tender, and the patient is unable to flex the distal phalanx. The end of the tendon with its bony fragment may be palpable.

PROXIMAL INTERPHALANGEAL JOINT INJURIES

Central Slip Injuries

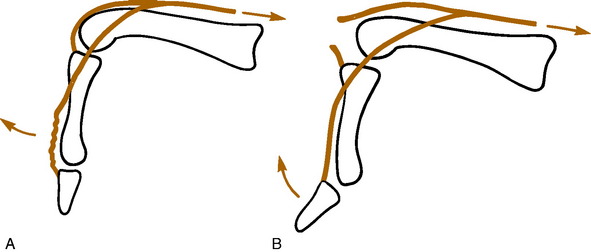

Damage to the central slip attachment to the middle phalanx is easily missed. Rupture can occur from forceful flexion of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint or in conjunction with a volar PIP dislocation. The PIP joint is usually swollen, and if injury to the slip is present, there is point tenderness on the dorsum of the joint. PIP extension may still be present because the lateral bands may not have migrated volarward yet. If the slip is completely avulsed, Elson’s test is usually positive (Fig. 15-26).

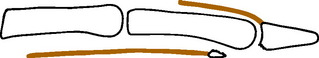

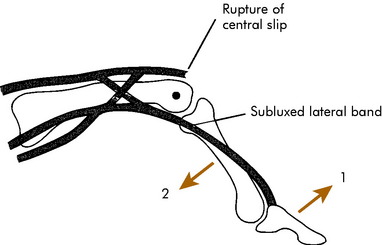

The diagnosis may be difficult. The injury often occurs in conjunction with the rare volar PIP dislocation. If untreated, the lateral bands may gradually migrate into a volar position, anterior to the axis of the PIP joint (Fig. 15-27). This may take 14 to 21 days. The lateral bands then become flexors of the PIP joint and hyperextend the DIP joint to produce the typical boutonnierre deformity. Late loss of DIP flexion is the most disabling problem.

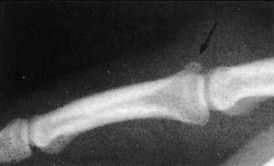

Roentgenograms are usually normal, although on rare occasions a fragment of bone may be avulsed (Fig. 15-28).

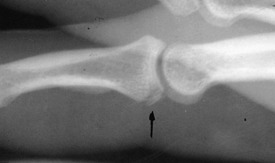

Volar Plate Injuries

A thickened part of the capsule called the volar plate normally acts to protect the PIP joint and prevent hyperextension. It can be avulsed (with or without a bony fragment) in conjunction with the common dorsal PIP dislocation or by a forced hyperextension to the joint (Fig. 15-29).

INTERPHALANGEAL DISLOCATIONS

These common injuries are almost always dorsal in direction and usually involve the PIP joint (Fig. 15-30). They are usually easily reduced. Although the volar plate may be damaged, dorsal dislocations are generally stable after reduction and may be treated by simply taping the finger to the adjacent finger for 3 to 4 weeks. Collateral ligament stability should always be evaluated. Unstable injuries should be referred. Volar PIP dislocations have the potential for central slip rupture and should probably be referred after reduction.

PROXIMAL INTERPHALANGEAL FRACTURE-DISLOCATIONS

Many minor IP joint injuries are accompanied by small avulsion fractures. If the joint is stable, the fracture can usually be ignored and the joint injury treated conservatively by splinting for 4 weeks. A more serious injury, sometimes called Wilson’s fracture, is the fracture-dislocation or subluxation of the PIP joint (Fig. 15-31). This injury should be suspected if any volar instability is present when the finger is tested in extension or if the volar fracture fragment is greater than 30% of the joint surface. These injuries should be referred. Special splinting is usually necessary, and surgery may even be indicated.

METACARPOPHALANGEAL DISLOCATIONS

These injuries are sometimes difficult to recognize. The index finger and thumb are more commonly involved. The proximal phalanx is usually displaced dorsally (Fig. 15-32). This injury often requires surgical reduction because the metacarpal head may buttonhole through the volar soft tissue. The more vigorous the attempt at reduction, the more the tissue tightens around the metacarpal neck. Closed reduction should be attempted, however, by hyperextending the joint and gradually reducing the phalanx. If the joint is stable, buddy taping for 3 weeks is sufficient. As after any reduction, the joint should “feel” reduced, and motion should be free. If the joint does not feel reduced, soft tissue interposition or an incomplete reduction should be suspected. Open reduction is then required. Referral is indicated if the joint is unstable.

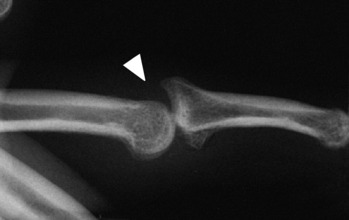

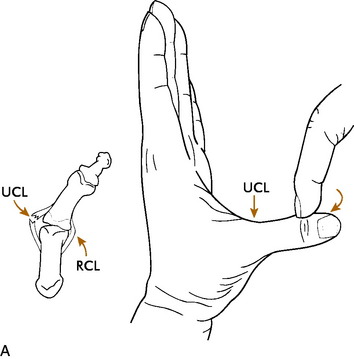

GAMEKEEPER’S THUMB AND SKIER’S THUMB (RUPTURED ULNAR COLLATERAL LIGAMENT)

The patient usually has a history of a sprained thumb, often from a fall on the hand. Chronic cases of UCL injury (called gamekeeper’s thumb) may have a history of instability, weakness with pinch, and recurrent effusions of the metacarpophalangeal joint. Local tenderness over the ligament and a joint effusion are usually present on physical examination. The ligamentous laxity is usually manifested clinically by valgus opening of the joint in both extension and flexion. This may be confirmed by abduction stress roentgenograms (Fig. 15-33). Plain radiographs to evaluate for avulsion fracture should be taken before any vigorous testing for stability to prevent displacing the fragment.

Radial collateral injuries of the thumb are much less common. Complete radial collateral ligament injuries are safely treated with a thumb spica cast. The rare case of persistent radial collateral ligament instability may benefit from late reconstruction.

Injuries to the Lower Extremity

THE KNEE

INJURIES TO LIGAMENTS

Along with fractures, these are the most important injuries to diagnose immediately. The first individual on the sideline has the best chance to evaluate the knee before spasm and swelling develop. As previously described (see Chapter 11), the knee should first be palpated for specific areas of tenderness. With the knee flexed 30 degrees, the collateral ligaments are evaluated, and Lachman’s test is performed. If possible, the cruciate ligaments are then tested with the knee flexed 90 degrees. Any acute rapid swelling within 12 hours suggests an anterior cruciate ligament rupture with hemarthrosis, especially if a “pop” is felt at the time of injury. (Swelling after 12 hours is usually caused by reactive synovitis, often the result of a meniscal tear.) If only a minor strain is present, it may be possible for the athlete to return to activity, but any more severe injury should have a compression dressing and ice applied, and the activity should be ceased pending further evaluation.

Plain roentgenograms should always be performed. Stress films may be especially helpful in the adolescent with open growth plates. In this age group, epiphyseal fractures are more common than ligamentous injuries because the growth plate is weaker than the ligaments (Fig. 15-34).

INJURIES TO THE MENISCUS

These are the most common of all knee injuries. They usually result from a twisting force applied to the knee with the extremity bearing weight. The athlete experiences sudden pain and is often unable to continue playing. Swelling develops gradually in contrast to ligament injury and may not be noticed until the following day. The pain may be localized to one joint line. The knee may actually lock if the meniscus is sufficiently torn and catches across the joint surface.

REHABILITATION

A program of progressively increasing exercises to improve strength and endurance is begun on all athletes with injured knees as soon as tolerated (see Chapter 11). Specific exercises to strengthen the quadriceps, hamstrings, and calf muscles are begun. Progressive range-of-motion exercises are added as tolerated, and the athlete is allowed to return to activities only when the effusion and pain have completely subsided and strength, range of motion, and thigh circumference have returned to normal.

THE ANKLE AND FOOT

ANKLE SPRAINS

The ankle sprain may be the most common of all athletic injuries. The lateral ligaments are the most frequently involved as a result of an inversion force (see Chapter 12). Mild to moderate sprains are best treated by early gentle motion (avoiding inversion) and exercise the day after the injury when pain begins to subside. Ice should be continued. Heat is never used. Peroneal muscle exercises are added and progressed against resistance as tolerated. More strenuous activity is allowed when the athlete is able to perform more vigorous activities such as hopping. Limited workouts may be resumed at this stage, but the ankle should always be taped. Return to full activity should not be allowed until there is full, pain-free motion and equal strength and the athlete is able to change direction quickly and jump without discomfort.

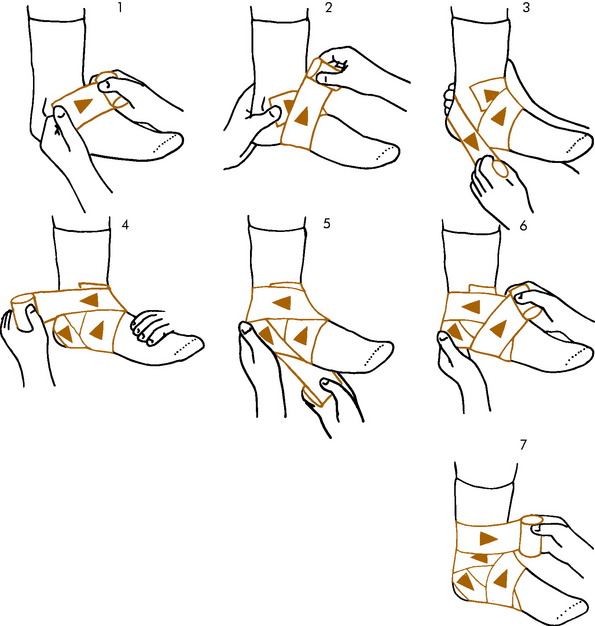

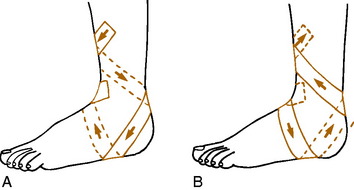

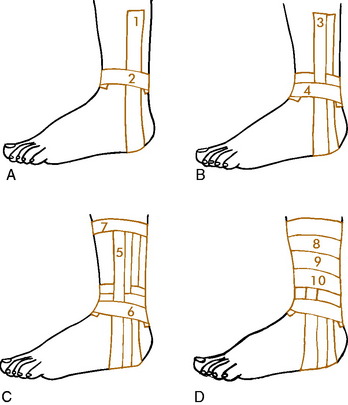

WRAPPING AND TAPING

To prevent ankle injury, many physicians and trainers advise wrapping the uninjured ankle (Fig. 15-35). A reusable dressing may be applied by the athlete over a sock. Even though half of the support of tape loosens in 10 minutes, the athlete who has had previous injury will benefit from taping when activity is resumed. For this individual, wrapping is probably not adequate, and applying adhesive tape is necessary to prevent reinjury. Adhesive taping is more beneficial because it can be applied tighter and extended as high on the leg as necessary for protection.

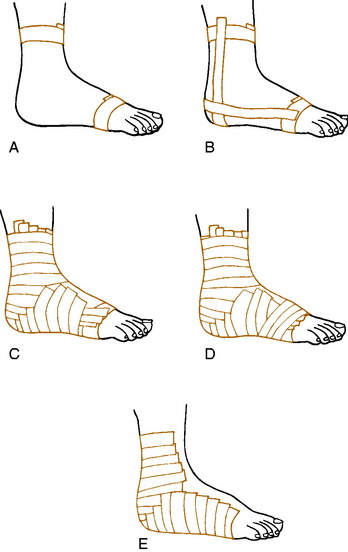

Several taping techniques are commonly used. Each physician should become familiar with a single method and learn to apply it easily. The closed basket weave described by Gibney is commonly used (Fig. 15-36). The open basket weave is the same except that the tape does not overlap in front. The open method may be used in acute sprains with excessive swelling because the tape is not circumferential and allows for swelling and ankle motion. An elastic wrap is applied over the open taping method.

The closed basket weave may be supplemented by a heel lock taping system for added medial or lateral support (Fig. 15-37). With any method, the ankle is first prepared by shaving and spraying with adhesive spray or tincture of benzoin. Either 1- or 1½-inch tape is normally used. Many modifications of these techniques are used (Figs. 15-38 and 15-39). Sensitivity to benzoin is possible; it must be used with caution.

ATHLETE’S FOOT

Many varieties of fungus affect the foot. The most common areas of involvement are between the toes and under the arch. Moisture and warmth predispose feet to the development of athlete’s foot. Itching, redness, and burning are present. Allergy to stockings or shoe materials should be ruled out. Treatment is with one of the many commercial or prescription medicated powders available. The foot should be kept dry, and stockings may need to be changed frequently. If symptoms persist, the newer antifungal agents are quite effective (see Chapter 12).

Miscellaneous Problems

AVULSION FRACTURES

Avulsions of the bony origin of muscles are common injuries in young athletes. The areas most commonly affected are (1) the coracoid process, (2) the greater tuberosity of the humerus, (3) the lesser and greater trochanters, (4) the iliac apophysis, (5) the ischial tuberosity, (6) the anterior superior iliac spine, and (7) the transverse and spinous processes of the vertebrae (Fig. 15-40).

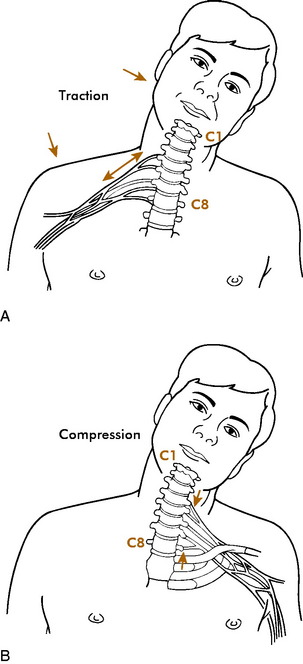

BRACHIAL PLEXUS INJURIES

An injury that is common in American football players is sometimes referred to as the burner or stinger. This injury results from the vulnerability of the brachial plexus or cervical roots to trauma during contact sports. Two mechanisms of injury are described. The most common is a stretch or traction injury of the upper brachial plexus caused by sudden depression of the shoulder with extension or lateral deviation of the neck to the opposite side (Fig. 15-41). The upper plexus is usually involved. It is characterized by sudden unilateral burning pain originating in the neck and radiating to the shoulder, arm, and hand. It does not usually follow a specific dermatome. It may be accompanied by weakness of the affected area, especially the deltoid, rotator cuff, and biceps.

EVALUATION

It is important to determine whether the injury is outside or inside the cervical spine. On-the-field screening should include an evaluation of (1) the location of pain and tenderness, (2) the amount of pain with isometric contraction of neck muscles, (3) deltoid, biceps, and triceps strength, and (4) range of neck motion. The last should be evaluated very carefully. Range of motion should not be tested if spine injury is suspected. When cervical spine injury has been ruled out, stretching the brachial plexus by pulling down the arm may elicit symptoms if the injury is due to traction. There may also be tenderness in the supraclavicular fossa. Spurling’s test (Chapter 3) may be positive in the patient with a compression injury.

If the neck examination is negative and complete recovery (full strength and motion with no pain or tenderness) occurs in 1 to 2 minutes, the athlete may return to play. Stretching the plexus should not reproduce symptoms. In most cases, the symptoms from burners subside quickly; often, they are not reported at all. A protective collar worn inside the shoulder pads may prevent further injury. Strengthening and range of motion exercises are recommended. Reinjury can be avoided by proper technique and good equipment.

TURF TOE

Turf toe is a general term that includes a number of injuries to the metatarsophalangeal joint of the great toe that are often caused by hyperextension. The diagnosis includes osteochondral and sesamoid injuries, sprains, and contusions. The incidence has increased with greater use of artificial playing surfaces. The injury may take several weeks to heal. The disorder is initially treated by ice and rest. A stiffer, solid shoe that inhibits movement of the forefoot may be tried, and figure-8 taping to limit motion is usually helpful. Some permanent loss of motion may result.

THE “LOOSE-JOINTED” ATHLETE

Loose-jointedness is often familial and affects the female athlete more often than the male. Laxity often diminishes during the late teenage years, but before that time is reached, this athlete is vulnerable to injury, especially at the shoulder and knee. This is commonly caused by a subluxing patella or ligament damage.

Adams JE. Bone injuries in very young athletes. Clin Orthop. 1969;58:129-140.

Cofield RH, Simonet WT. The shoulder in sports. Mayo Clin Proc. 1984;59:157-164.

James SL. Running injuries to the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1995;3:309-318.

James SL, Bates BT, Osternig LR. Injuries to runners. Am J Sports Med. 1978;6:40-50.

Light TR. Buttress pinning techniques. Orthop Rev. 1981;10:49-55.

Montgomery SC, Miller MD. What’s new in sports medicine. J Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87:686-694.

Shah SN, Miller BS, Kuhn JE. Chronic exertional compartment syndrome. Am J Orthop. 2004;33:335-341.

Tullos HS, King JW. Lesions of the pitching arm in adolescents. JAMA. 1972;220:264-271.