Chapter 84 Spondylolisthesis

Sagittal Plane Lumbar Spine Deformity Correction

As its name suggests, spondylolisthesis is characterized by a slip in vertebral alignment. However, it is the associated sagittal imbalance that often carries more significance and may result in a symptomatic lumbar kyphosis.1 This chapter focuses on spondylolisthesis as a condition of lumbar sagittal plane imbalance.

Etiology and Types of Spondylolisthesis

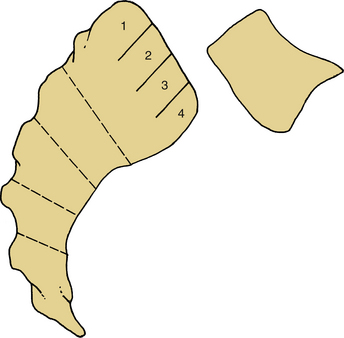

Spondylolisthesis is also graded in severity from 1 to 5 according to the Meyerding system.1 Grades 1 and 2 are termed low-grade, while the remainder are considered high-grade (Fig. 84-1).

Several classification systems have been developed, but Wiltse’s classification from 1957 remains useful and focuses on the etiology of the slip2 (Box 84-1). It focuses on the dorsal elements, which counteract the forces discussed previously. The most commonly encountered types are the isthmic and degenerative types, and discussion of these will occupy the bulk of this chapter.

Congenital Spondylolisthesis

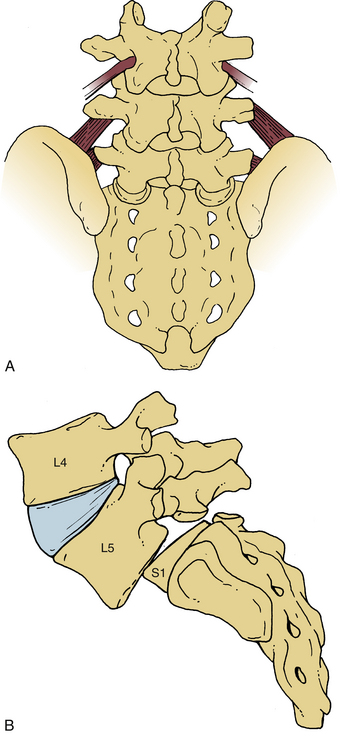

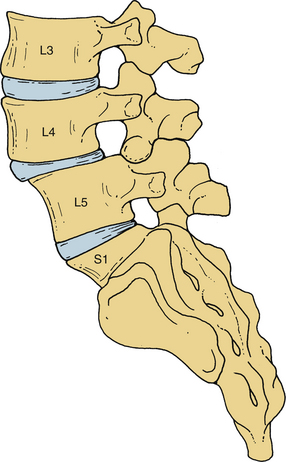

A congenitally dysplastic dorsal arch, which includes the pars interarticularis and facet joints, allows for misalignment across a vertebral segment (Fig. 84-2). These defects are commonly seen at the L5 level (in a case of L5-S1 spondylolisthesis) but may include abnormalities of the sacral ala or superior articular facet.3

Isthmic Spondylolisthesis

Isthmic spondylolisthesis (IS) represents the most common form of spondylolisthesis (Fig. 84-3). In contrast to the congenital form, it is more common in males. Therefore, when found in females, it tends to represent a more significant condition, with more severe symptoms and a higher rate of progression.

IS is most commonly seen at the L5-S1 level. Some consideration has been given to anatomic factors such as pelvic incidence4–7 and lumbosacral transitional vertebrae.8

There is a familial and genetic predisposition to IS. Relatives of IS patients have a 30% or more increased risk of having the disorder.9–11 Inuit Eskimos have up to a 50% incidence of IS in their population, compared to 6% quoted for the general population and 2.8% in people of African descent.

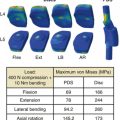

While genetics plays a role, there is strong evidence for environmental factors in the development of IS. Factors that place increased force across the vertebral column, especially the lower lumbar spine, may result in fatigue fracture of the pars interarticularis, with resultant ventrolisthesis. The bipedal, erect gait of humans places greater stress across the lordotic lower lumbar spine than is seen in animals that have a quadruped gait. Activities that further accentuate the lordosis, such as hyperextension, exacerbate this picture. Therefore, adolescents who are involved in sports such as gymnastics, weight lifting, swimming, and diving have been known to display a higher incidence of symptomatic spondylolysis.10–12

Wiltse demonstrated that most cases of spondylolisthesis present before the end of the first decade. Fredrickson demonstrated a 6% incidence of spondylolisthesis in the general population.10 Saraste noted earlier disc degeneration at the level of the slip, and risk factors for back pain included spondylolysis at the L4 level and greater than 25% slip.11

In Frederickson’s 45-year follow-up study, only 5% of patients demonstrated progression. However, when the most symptomatic patients are followed, the incidence appears higher, at 20%. When progression occurs in the adult years, it usually results in no worse than a grade 2 slip.10

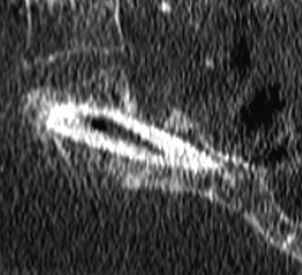

Risk factors associated with progression include skeletal immaturity associated with a high-grade slip. A high slip angle (>50 degrees) may predict progression.5,13,14 The slip angle is measured between a line drawn along the superior end plate of L5 and the perpendicular to another line drawn along the dorsal vertebral border of S1 (Fig. 84-4). A high angle signifies kyphosis.

FIGURE 84-4 Horizontal or sagittal facet joint alignment predisposes to degenerative spondylolisthesis.

Most authors contend that progression of the slip after skeletal maturity occurs as a result of disc degeneration below the level of the slip. Patients may present early or late in life. During adolescence, symptoms relate to the pars fracture and include axial back pain with or without leg pain. In later adult life (after age 50 years), discogenic back pain and radicular leg pain related to worsening foraminal stenosis become a problem. Patients who present early in life are felt to represent a different group than the 6% of the general population with pars defects (who may or may not be symptomatic and have an incidence of back pain that follows that of the general population).13

While the pars fracture may or may not heal, once a slip has occurred, it is thought to persist, if not progress, with time. Only a single case report exists documenting spontaneous resolution of a slip in an adolescent patient.15

Degenerative Spondylolisthesis

Degeneration of the intervertebral disc and facet joints may lead to degenerative spondylolisthesis (DS). A degenerative disc has been shown to be less capable of resisting shear stress and can place additional stress on the facet joints.16,17 Degeneration of the facets leads to their inability to guide normal intervertebral motion and maintain alignment. Facet joint orientation in the sagittal plane predisposes the segment to misalignment (see Fig. 84-4). This is most commonly seen at the L4-5 level, and the presence of strong lumbopelvic ligaments across the L5-S1 interspace is felt to transfer stress to the L4-5 level, resulting in preferential involvement here.18 Pelvic incidence may also play a role in the development of L4-5 DS.19

Iatrogenic Spondylolisthesis

An overly aggressive surgical decompression that does not respect the need for preservation of at least half the facet joint and 1 cm of the pars interarticularis places the patient at risk for iatrogenic intraoperative or postoperative fracture and spondylolisthesis (Fig. 84-5). This condition is poorly tolerated and almost uniformly involves revision surgery, which has a higher rate of complications.20

Presentation

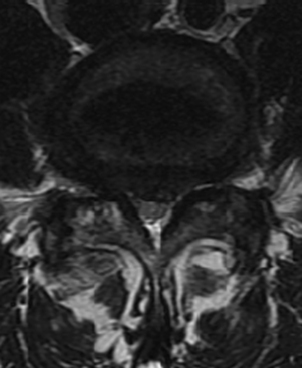

Patients typically present with a complaint of back and leg pain. The pain is typically mechanical, positional, and activity-related. Leg pain may be radicular and dermatomal in nature or be associated with neurogenic claudication. Such claudication symptoms are seen in DS patients with central stenosis (Fig. 84-6) and include cramping bilateral buttock and thigh pain, “discomfort,” or “fatigue.” This improves with postural changes, including flexion and rest. Patients tend to lean on a cart at the supermarket, on a bench at the park, or on furniture and countertops at home. They describe less difficulty going up hills (in a relatively flexed position) than down. They may also be able to ride a bicycle (again placing the lumbar spine in a flexed position) for far longer than they are able to walk. IS patients, on the other hand, commonly suffer from radicular symptoms related to foraminal stenosis (Fig. 84-7). “Pseudoradicular” leg pain has been described in IS patients who demonstrate more of a referred type of leg pain pattern that does not fit a specific dermatome.

DS patients have been noted to have a higher body mass index.21 They are often limited in their mobility and may demonstrate difficulty in the physician’s office when transitioning between sitting and standing, owing to development of proximal gluteal and quadriceps weakness. Extension is limited and painful, some patients being unable to stand erect during an acute exacerbation.

Imaging

Plain lateral radiographs will show a slip, and this may be more evident on flexion-extension radiographs in cases of dynamic instability. A pars fracture may be visible on anteroposterior or lateral images. Oblique radiographs show the pars en face, and the fracture can be seen as a collar on the “scotty dog.” In cases of high-grade slips with compensatory pelvic verticalization, a “heart-shaped” pelvis is seen. Radiographs should be obtained in the upright position, as the slip may reduce in the supine position. Lateral radiographs should be obtained in the true lateral position, as even slight rotation may result in an underappreciation for the degree of slip.22

While patients with spondylolysis alone (without listhesis) do not demonstrate radiographic abnormalities in spine morphology, those with IS do have a high lordosis angle, L5 vertebral body wedging, and L4-5 disc wedging. In DS, spine morphology shows wedging of the L5 vertebral body but less wedging of intervertebral discs.7,23–26

Adolescents presenting with low back pain commonly have pars fractures that may or may not show on plain radiograph, or even on bone scan or MRI. Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scans have an increased sensitivity for detection of spondylolysis.27

Radiographic predictors of instability include spondylolisthesis, facet widening, end-plate degenerative changes, sagittal facet orientation, and facet sclerosis, widening of the facet being more associated with dynamic instability.28–30 Lumbosacral transitional anatomy may be a contributor as well.8

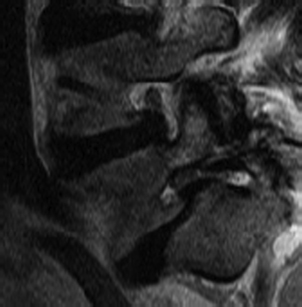

MRI scanning is considered for patients with complaints of leg pain or those who are to undergo surgical intervention. Neural compression can be detected in this manner, as can synovial cysts and facet joint effusions, which have a correlation with spondylolisthesis.28–31 Symptoms can be correlated with degree of intervertebral disc degeneration associated with the spondylolisthesis.16 In cases of pathologic spondylolisthesis, MRI assists the surgeon in delineation of an associated soft tissue mass and the extent of metastatic spread. The degree of slip cannot be assessed reliably on such scans, and some slips are missed secondary to spontaneous postural reduction in the supine position in the MRI scanner. Newer technology, allowing for functional MRI scans in the upright position, have on occasion detected greater pathology.14,32

Nonsurgical Treatment

Nonoperative management of IS patients includes observation with activity restriction and physical therapy for instruction in a flexion exercise program. Bracing with a soft corset, a hard clamshell lumbosacral orthosis, and formal casting have all been employed with success in adolescent patients with a “hot” spondylolysis (i.e., one that is active on bone scan, with physiologic potential for healing, whether fibrous or bony).33–35

In the skeletally immature patient, a low-grade slip should be observed with serial radiographs every 6 months until skeletal maturity.36 Symptomatic patients should have activities restricted, and consideration may be given to bracing. Adolescent patients with high-grade slips or a high slip angle are at risk for progression and are offered surgery.

A formal regimen of exercises performed under the dutiful eye of a good physical therapist can be of tremendous benefit, not only in assuaging a patient’s acute symptoms but also in training for proper “back hygiene.” Patients receive instruction on how to avoid activities or injuries that would contribute to future episodes. Exercises focus on flexion, which limits forces across a painful spondylolysis or a painful facet and can increase neural canal and foraminal dimensions, resulting in improvement of radicular symptoms. Lumbar traction is of variable benefit and may provide a counter to associated muscle spasm.37 Patients benefit most in acutely painful (<6 weeks) situations. Chiropractic care often employs modalities similar to those of physical therapy but may focus on passive interventions such as mobilization and manipulation, ultrasound, and electrical stimulation.35,38

Epidural steroid injections are of significant benefit to the patient with radicular leg pain, with the potential for significant symptomatic relief in an expedited fashion. A series of up to four injections in concert with other treatments can allow patients who would otherwise be considered surgical candidates to avoid surgery.39

While nonoperative treatment of DS is often helpful, it has been shown not to be as effective as surgery in the long term.40 The symptoms associated with chronic conditions such as DS with stenosis do not respond to nonoperative treatment as well as do more acute conditions afflicting the spine, such as disc herniations.

Surgical Treatment

Indications

Indications for surgery include a progressive slip in a skeletally immature adolescent patient, unrelenting back or leg pain for which nonoperative treatment has failed, and progressive neurologic deficit. Patients with primarily leg pain rather than back pain are more likely to benefit from surgery.41

Pars Repair

Adolescents who fail nonoperative treatment and have persistent symptoms from IS may benefit from direct pars repair.42,43 Surgical candidates should possess a healthy intervertebral disc and have minimal, if any, slip.16,44 A positive transient response to pars injection suggests that the pars is indeed the pain generator and assists in patient selection. The advantage of such a procedure lies in its ability to spare fusion of a motion segment.

Decompression Alone

Initial studies have demonstrated a 25% to 50% postoperative progression of slips, especially in patients under the age of 30, with resultant poor outcomes45,46 (Fig. 84-8).

Recent attention to minimally invasive techniques has directed greater focus toward a unilateral approach to laminectomy or toward bilateral laminotomy, with preservation of midline structures as a treatment option for decompression of low-grade slips without dynamic instability.47

Fusion Alone

Fusion alone has been more commonly done in IS patients without symptoms of neurologic compression in whom a reduction is not attempted. A single-level L5-S1 instrumented fusion is performed for low-grade slips, and a two-level L4-S1 fusion is done in cases of high-grade slips, owing to difficulty in accessing the L5 transverse process through the slips. Carragee noted that the addition of a decompression to the fusion placed his patients at increased risk for pseudarthrosis and poor outcome.48

Decompression and Fusion

Again, earlier studies showed that patients who underwent a concomitant fusion along with decompression had a lower rate of slip progression and better clinical outcomes. Herkowitz and Kurz published an often-cited early paper that showed improved outcomes in patients who underwent fusion.46 In a follow-up study, Fischgrund then demonstrated that outcomes correlated with solid fusion and that the addition of instrumentation correlated with achievement of a solid fusion.49 Multiple studies have similarly confirmed that addition of instrumentation results in improved fusion rates, and this has at times correlated with improved outcomes.50–52

Noninstrumented fusion, while beneficial from a short-term cost-analysis perspective, has fallen somewhat out of favor except for elderly or severely osteoporotic patients, who would benefit from shorter operative times and a potentially lower infection rate.53

Patients with over 2 mm of dynamic instability on flexion-extension radiographs are likely to have persistent symptoms when a noninstrumented fusion is performed.54 Instrumented fusion began gaining favor as a technique for maintenance of reduction and achievement of a more robust fusion.49,55

A randomized study of patients with DS demonstrated superiority in outcomes for surgically treated patients.55 While nonsurgical treatment is of benefit in many patients, it tends to be short-lived, and the degree of improvement lags behind that noted after surgery.

The specific approach to fusion, whether dorsolateral or interbody, is the subject of much debate. Various studies point to the superiority of one approach over the other, but the approach that is utilized for low-grade slips remains a matter of surgeon preference.56–58

Ventral Surgery

Surgeons have employed ventral stand-alone interbody fusion for cases of spondylolisthesis. However, the majority of data on ventral surgery relate to circumferentially treated patients who undergo dorsal instrumentation with or without formal dorsal supplementary fusion.59,60 Sacral fractures have been noted that are thought to be secondary to a lack of dorsal tension-band support.61 Ventral surgery serves primarily as an adjunct to dorsal surgery to enhance fusion and improve alignment.

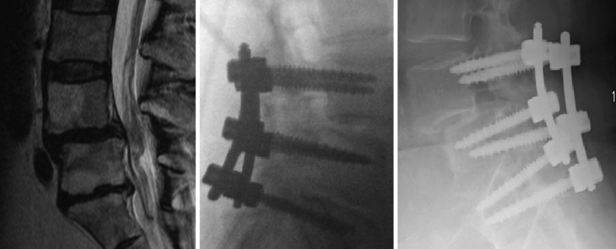

Bohlman Technique

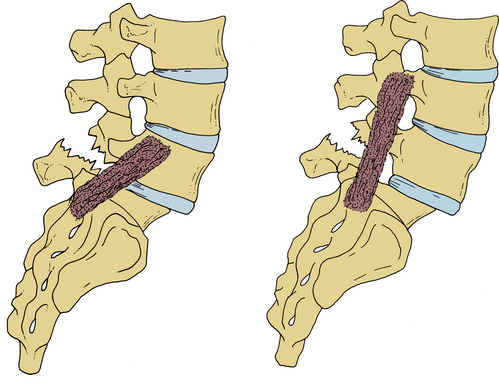

The Bohlman technique, as well as variations of it, has been employed in high-grade spondylolisthesis. A fibular graft is placed across the L5-S1 interspace from a dorsal approach (Fig. 84-9). Excellent outcomes have been reported with this stabilization technique when accompanied by instrumentation from L4 to S1, even without reduction of the slip. Some reduction in slip angle usually occurs with intraoperative prone positioning.62

Transsacral screws have also been employed with standard pedicle screw stabilization of L4, followed by screw placement from S1 across the L5-S1 disc space and into the L5 body. Results have been shown to be equivalent to those of a transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with reduction of the slip.63 This technique may be employed with or without fibular interbody strut grafting.64,65

Gaines Procedure

The Gaines procedure has been utilized in cases of spondyloptosis, or complete dislocation of the vertebrae (grade 5 slip). The L5 vertebra is resected from a ventral approach, thus shortening the spinal column, and the L4 vertebra is then docked onto the sacrum, locking it in place with dorsal instrumentation.66 A modified Gaines procedure involves excision of the inferior half of the body of L5 ventrally combined with dorsal reduction and fusion.67 A three-stage shortening procedure for high-grade slips has also been described.68

Controversies

Slip Reduction

Historically, high-grade slips have been treated with a reduction prior to stabilization and fusion. Attempts at reduction included the use of preoperative traction, but postreduction casting would not allow sufficient focal control over the subluxed vertebrae to allow for maintenance of correction.3

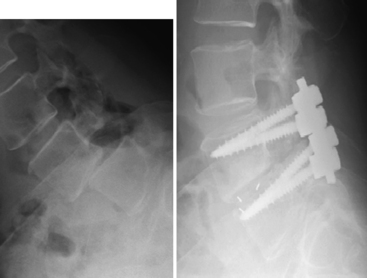

Reduction of a high-grade slip is beneficial in that it allows for a greater surface area of contact between vertebrae available for fusion. An interbody spacer may then be placed, allowing for anterior column support and unloading of stress placed on dorsal instrumentation, with potential for increased fusion rates56 (Fig. 84-10). Reduction is also associated with greater cosmetic appeal and satisfaction.

FIGURE 84-10 Reduction of a slip allows for placement of an interbody spacer and decreases stress on posterior instrumentation.

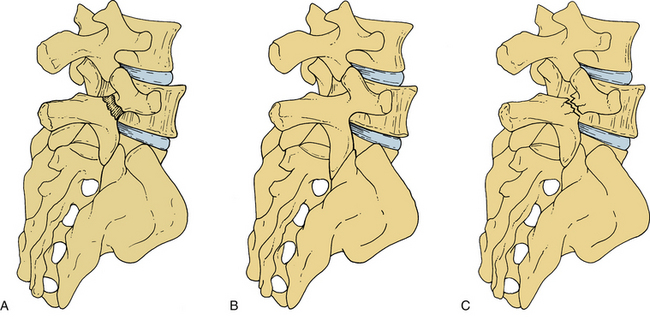

Decompression of the neural elements is essential before any attempt at reduction. Concern arises for traction- or compression-related injury to nerve roots, especially the exiting roots as the vertebral body is reduced dorsally toward the superior articular facet of the vertebra below. Instrumented fusion after decompression allows for visualization of nerve roots during the reduction procedure, and has a lower rate of neural injury, with good results.49,54,69 Partial reduction of the slip, with a greater emphasis on reduction of the slip angle, may be safely performed (Fig. 84-11).

Recent attention has been drawn toward reduction of lower-grade slips rather than performance of an in situ fusion. Newer instrumentation includes reduction screws and devices to gradually pull a screw in the slipped vertebral body back into reduction. Other techniques utilize postural reduction in the prone position (with extension of the hips following decompression and instrumentation) and in situ bending of rods.

Instrumentation

The addition of instrumentation to a fusion construct adds significant expense to an operation whose cost is already questioned in many circles. Its legitimacy arises from data that show an improved fusion rate with the use of instrumentation, which is felt to correlate with improved outcomes. Instrumentation is beneficial in achieving and maintaining reduction and in decreasing reliance on external bracing. However, a randomized trial evaluating instrumented fusions in IS patients has not shown improvement in clinical outcome.48

Approach: Ventral-Dorsal versus Dorsal Alone

The addition of an interbody fusion may be achieved through a separate ventral-dorsal approach or through a single-incision approach. Ventral approaches afford the opportunity for a more complete discectomy and placement of a larger graft or cage for fusion. Greater restoration of foraminal height and lordosis is possible. Thus, this is appealing in cases of high-grade slips. The lumbosacral junction is often approached with a ventral-dorsal surgery to maximize the fusion rate across this transitional segment. Some authors have found improved outcomes with a combined ventral-dorsal approach, regardless of level treated.60 There is some evidence that ventral-dorsal fusion may be more cost-effective, as it may contribute to solid arthrodesis and a lower chance for reoperation.70 For most low-grade slips in patients requiring single-level surgery, however, studies have shown no consistent benefit to the addition of an interbody fusion.57

Short-term studies have evaluated the utility of various “new technologies” in the spine surgeon’s armamentarium. These include dynamic stabilization devices such as interspinous distraction devices and pedicle-screw-based devices. 71–76 However, only a small percentage of traditionally treated patients qualify for these procedures, and long-term results are lacking.71 Novel approaches to interbody fusion, such as the AxiaLIF (TranS1, Wilmington, NC)77,78 and extreme lateral interbody fusion,79,80 have been of utility in providing a minimally invasive approach to traditional fusion. Some authors have suggested that the indirect decompression that is achieved through such approaches is sufficient to address stenosis, yet revision surgery for formal decompression has been necessary in a number of cases.81

Complications

In an evaluation of over 10,000 surgical cases, the rate of total complications for treatment of DS and IS was 9.2%. The complication rate was higher in patients with high-grade spondylolisthesis, those with a diagnosis of DS, and older patients.20

Dural tear is higher in patients undergoing surgery for spondylolisthesis than in those undergoing surgery for other lumbar conditions.82

Rates of neural injury are higher in cases of complete reduction of a slip. If a reduction is attempted, the exiting nerve root should be decompressed completely along its length through the foramen. Nerve injury is thought to occur secondary to traction during final stages of a complete anatomic reduction, and recommendations have been made to focus on partial reduction of the slip with a greater focus on reduction of the slip angle and kyphotic deformity. Use of neurologic monitoring with EMG and motor-evoked potentials can help in detecting intraoperative nerve root injury.69

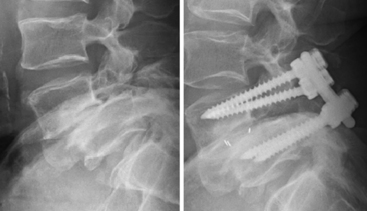

Progression of a slip may occur in cases of decompression without fusion. Even in cases of fusion, progression has been noted, especially in noninstrumented cases (in which a pseudarthrosis may be present). Loss of fixation may occur in instrumented cases secondary to osteoporosis in elderly patients (Fig. 84-12).

Pseudarthrosis rates are higher in cases of high-grade slips. A high slip angle (>50 degrees) and the addition of a decompression are risk factors as well.

Adjacent-segment degeneration may occur at a relatively lower rate in adult low-grade IS compared with other degenerative lumbar spine diseases. Segmental lordosis is significantly correlated with adjacent-segment degeneration, and restoration of normal lordosis may have a role in preventing adjacent-segment degeneration. While interbody fusions (whether performed ventral-dorsal or through a single incision) add to construct stability and in some cases to a higher fusion rate, they have been associated with an increased rate of adjacent-segment degeneration.83

DS is often encountered at the L4-5 level, and it is unclear whether an isolated L4-5 fusion (“floating fusion”) adjacent to a degenerative L5-S1 segment is adequate or whether inclusion of the L5-S1 segment should be performed.84

Hardware failure is a potential complication in multilevel cases and in patients with osteoporosis. Interbody fusion cages are at risk for displacement and subsidence through osteoporotic vertebral end plates. Caution must be utilized in the use of implants in such patients. Care should also be taken to avoid an excessively wide decompression (in the absence of severe foraminal stenosis) that would further destabilize a segment, especially in the case of a spondylolisthesis across a tall and mobile disc space (see Fig. 84-12).

Ben-Galim P., Reitman C.A. The distended facet sign: an indicator of position-dependent spinal stenosis and degenerative spondylolisthesis. Spine J. 2007;7(2):245-248.

Beutler W.J., Fredrickson B.E., Murtland A., et al. The natural history of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: 45-year follow-up evaluation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28(10):1027-1035. discussion 1035

Gaines RW: L5 vertebrectomy for the surgical treatment of spondyloptosis: thirty cases in 25 years. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(Suppl 6):S66-S70.

Fischgrund J.S., Mackay M., Herkowitz H.N., et al. Volvo Award winner in clinical studies. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis: a prospective, randomized study comparing decompressive laminectomy and arthrodesis with and without spinal instrumentation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22(24):2807-2812.

Weinstein J.N., Lurie J.D., Tosteson T.D., et al. Surgical compared with nonoperative treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. Four-year results in the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) randomized and observational cohorts. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2009;91(6):1295-1304.

1. Meyerding H.W. Spondylolisthesis; surgical fusion of lumbosacral portion of spinal column and interarticular facets: use of autogenous bone grafts for relief of disabling backache. J Int Coll Surg. 1956;26(5 Part 1):566-591.

2. Wiltse L.L. Etiology of spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1957;10:48-60.

3. Newman P.H. A clinical syndrome associated with severe lumbo-sacral subluxation. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1965;47:472-481.

4. Hanson D.S., Bridwell K.H., Rhee J.M., Lenke L.G. Correlation of pelvic incidence with low- and high-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27(18):2026-2029.

5. Jackson R.P., Phipps T., Hales C., Surber J. Pelvic lordosis and alignment in spondylolisthesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28(2):151-160.

6. Huang R.P., Bohlman H.H., Thompson G.H., Poe-Kochert C. Predictive value of pelvic incidence in progression of spondylolisthesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28(20):2381-2385. discussion 2385

7. Yue W.M., Brodner W., Gaines R.W. Abnormal spinal anatomy in 27 cases of surgically corrected spondyloptosis: proximal sacral endplate damage as a possible cause of spondyloptosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(Suppl 6):S22-S26.

8. Kim N.H., Suk K.S. The role of transitional vertebrae in spondylolysis and spondylolytic spondylolisthesis. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 1997;56(3):161-166.

9. Wynne-Davies R., Scott J.H. Inheritance and spondylolisthesis: a radiographic family survey. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1979;61(3):301-305.

10. Fredrickson B.E., Baker D., McHolick W.J., et al. The natural history of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1984;66(5):699-707.

11. Saraste H. Long-term clinical and radiological follow-up of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1987;7(6):631-638.

12. Commandre F.A., Gagnerie G., Zakarian M., et al. The child, the spine and sport. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1988;28(1):11-19.

13. Beutler W.J., Fredrickson B.E., Murtland A., et al. The natural history of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: 45-year follow-up evaluation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28(10):1027-1035. discussion 1035

14. Ferreiro Perez A., Garcia Isidro M., Ayerbe E., et al. Evaluation of intervertebral disc herniation and hypermobile intersegmental instability in symptomatic adult patients undergoing recumbent and upright MRI of the cervical or lumbosacral spines. Eur J Radiol. 2007;62(3):444-448.

15. Blatter S.C., Min K., Huber H., Ramseier L.E. Spontaneous reduction of spondylolisthesis during growth: a case report. J Pediatr Orthop B. April 12, 2011. [Epub ahead of print]

16. Osterman K., Schlenzka D., Poussa M., et al. Isthmic spondylolisthesis in symptomatic and asymptomatic subjects, epidemiology, and natural history with special reference to disk abnormality and mode of treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;297:65-70.

17. Iatridis J.C., Kumar S., Foster R.J., et al. Shear mechanical properties of human lumbar annulus fibrosus. J Orthop Res. 1999;17(5):732-737.

18. Leong J.C., Luk K.D., Chow D.H., Woo C.W. The biomechanical functions of the iliolumbar ligament in maintaining stability of the lumbosacral junction. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1987;12(7):669-674.

19. DePalma A.F., Rothman R.H. The nature of pseudarthrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1968;59:113-118.

20. Sansur C.A., Reames D.L., Smith J.S., et al. Morbidity and mortality in the surgical treatment of 10,242 adults with spondylolisthesis. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;13(5):589-593.

21. Kalichman L., Guermazi A., Li L., Hunter D.J. Association between age, sex, BMI and CT-evaluated spinal degeneration features. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2009;22(4):189-195.

22. Löwe A., Hopf C., Eysel P. Significance of exact lateral roentgen documentation in Meyerding’s grading of spondylolistheses. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1996;134(3):210-213.

23. Dai L.Y. Disc degeneration in patients with lumbar spondylolysis. J Spinal Disord. 2000;13(6):478-486.

24. Crawford N.R., Cagli S., Sonntag V.K., Dickman C.A. Biomechanics of grade I degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. Part 1: in vitro model. J Neurosurg. 2001;94(Suppl 1):45-50.

25. Aono K., Kobayashi T., Jimbo S., et al. Radiographic analysis of newly developed degenerative spondylolisthesis in a mean twelve-year prospective study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35(8):887-891.

26. Been E., Li L., Hunter D.J., Kalichman L. Geometry of the vertebral bodies and the intervertebral discs in lumbar segments adjacent to spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: pilot study. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(7):1159-1165.

27. Zukotynski K., Curtis C., Grant F.D., et al. The value of SPECT in the detection of stress injury to the pars interarticularis in patients with low back pain. Orthop Surg Res. 2010;5:13.

28. Ben-Galim P., Reitman C.A. The distended facet sign: an indicator of position-dependent spinal stenosis and degenerative spondylolisthesis. Spine J. 2007;7(2):245-248.

29. Chaput C., Padon D., Rush J., et al. The significance of increased fluid signal on magnetic resonance imaging in lumbar facets in relationship to degenerative spondylolisthesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(17):1883-1887.

30. Oishi Y., Murase M., Hayashi Y., et al. Smaller facet effusion in association with restabilization at the time of operation in Japanese patients with lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;12(1):88-95.

31. Alicioglu B., Sut N. Synovial cysts of the lumbar facet joints: a retrospective magnetic resonance imaging study investigating their relation with degenerative spondylolisthesis. Prague Med Rep. 2009;110(4):301-309.

32. Jinkins J.R., Dworkin J.S., Damadian R.V. Upright, weight-bearing, dynamic-kinetic MRI of the spine: initial results. Eur Radiol. 2005;15(9):1815-1825.

33. Steiner M.E., Micheli L.J. Treatment of symptomatic spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis with the modified Boston brace. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1985;10(10):937-943.

34. van den Oever M., Merrick M.V., Scott J.H. Bone scintigraphy in symptomatic spondylolysis. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1987;69(3):453-456.

35. Sys J., Michielsen J., Bracke P., et al. Nonoperative treatment of active spondylolysis in elite athletes with normal X-ray findings: literature review and results of conservative treatment. Eur Spine J. 2001;10(6):498-504.

36. Agabegi S.S., Fischgrund J.S. Contemporary management of isthmic spondylolisthesis: pediatric and adult. Spine J. 2010;10(6):530-543.

37. Krause M., Refshauge K.M., Dessen M., Boland R. Lumbar spine traction: evaluation of effects and recommended application for treatment. Man Ther. 2000;5(2):72-81.

38. Möller H., Hedlund R. Surgery versus conservative management in adult isthmic spondylolisthesis: a prospective randomized study: part 1. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(13):1711-1715.

39. Riew K.D., Yin Y., Gilula L., et al. The effect of nerve-root injections on the need for operative treatment of lumbar radicular pain. A prospective, randomized, controlled, double-blind study. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2000;82(11):1589-1593.

40. Weinstein J.N., Lurie J.D., Tosteson T.D., et al. Surgical compared with nonoperative treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. Four-year results in the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) randomized and observational cohorts. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2009;91(6):1295-1304.

41. Pearson A., Blood E., Lurie J., et al. Predominant leg pain is associated with better surgical outcomes in degenerative spondylolisthesis and spinal stenosis: results from the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT). Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36(3):219-229.

42. Bradford D.S., Iza J. Repair of the defect in spondylolysis or minimal degrees of spondylolisthesis by segmental wire fixation and bone grafting. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1985;10(7):673-679.

43. Hirabayashi S., Kumano K., Kuroki T. Cotrel-Dubousset pedicle screw system for various spinal disorders. Merits and problems. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1991;16:1298-1304.

44. Giudici F., Minoia L., Archetti M., et al. Long-term results of the direct repair of spondylolisthesis. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(Suppl 1):S115-S120.

45. Herron L.D., Trippi A.C. L4-5 degenerative spondylolisthesis. The results of treatment by decompressive laminectomy without fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1989;14(5):534-538.

46. Herkowitz H.N., Kurz L.T. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis. A prospective study comparing decompression with decompression and intertransverse process arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1991;73(6):802-808.

47. Hong S.W., Choi K.Y., Ahn Y., et al. A comparison of unilateral and bilateral laminotomies for decompression of L4-5 spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36(3):E172-E178.

48. Carragee E.J. Single-level posterolateral arthrodesis, with or without posterior decompression, for the treatment of isthmic spondylolisthesis in adults. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1997;79(8):1175-1180.

49. Fischgrund J.S., Mackay M., Herkowitz H.N., et al. 1997 Volvo Award winner in clinical studies. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis: a prospective, randomized study comparing decompressive laminectomy and arthrodesis with and without spinal instrumentation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22(24):2807-2812.

50. Bridwell K.H., Sedgewick T.A., O’Brien M.F., et al. The role of fusion and instrumentation in the treatment of degenerative spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis. J Spinal Disord. 1993;6:461-472.

51. Markwalder T.M. Surgical management of neurogenic claudication in 100 patients with lumbar spinal stenosis due to degenerative spondylolisthesis. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1993;120:136-142.

52. Deguchi M., Rapoff A.J., Zdeblick T.A. Posterolateral fusion for isthmic spondylolisthesis in adults: analysis of fusion rate and clinical results. J Spinal Disord. 1998;11(6):459-464.

53. Carreon L.Y., Puno R.M., Dimar J.R.2nd, et al. Perioperative complications of posterior lumbar decompression and arthrodesis in older adults. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2003;85(11):2089-2092.

54. Thomsen K., Christensen F.B., Eiskjaer S.P., et al. Volvo Award winner in clinical studies. The effect of pedicle screw instrumentation on functional outcome and fusion rates in posterolateral lumbar spinal fusion: a prospective, randomized clinical study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22(24):2813-2822.

55. Möller H., Hedlund R. Instrumented and noninstrumented posterolateral fusion in adult spondylolisthesis–a prospective randomized study: part 2. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(13):1716-1721.

56. Swan J., Hurwitz E., Malek F., et al. Surgical treatment for unstable low-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis in adults: a prospective controlled study of posterior instrumented fusion compared with combined anterior-posterior fusion. Spine J. 2006;6(6):606-614.

57. Abdu W.A., Lurie J.D., Spratt K.F., et al. Degenerative spondylolisthesis: does fusion method influence outcome? Four-year results of the spine patient outcomes research trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(21):2351-2360.

58. Pateder D.B., Benzel E. Noninstrumented facet fusion in patients undergoing lumbar laminectomy for degenerative spondylolisthesis. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2010;19(3):153-158.

59. Kim J.S., Kang B.U., Lee S.H., et al. Mini-transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion versus anterior lumbar interbody fusion augmented by percutaneous pedicle screw fixation: a comparison of surgical outcomes in adult low-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2009;22(2):114-121.

60. Kim J.S., Lee K.Y., Lee S.H., et al. Which lumbar interbody fusion technique is better in terms of level for the treatment of unstable isthmic spondylolisthesis? J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;12(2):171-177.

61. Lastfogel J.F., Altstadt T.J., Rodgers R.B., Horn E.M. Sacral fractures following stand-alone L5-S1 anterior lumbar interbody fusion for isthmic spondylolisthesis. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;13(2):288-293.

62. Heller J.G., Ghanayem A.J., McAfee P., Bohlman H.H. Iatrogenic lumbar spondylolisthesis: treatment by anterior fibular and iliac arthrodesis. J Spinal Disord. 2000;13(4):309-318.

63. Smith J.A., Deviren V., Berven S., et al. Clinical outcome of trans-sacral interbody fusion after partial reduction for high-grade l5-s1 spondylolisthesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26(20):2227-2234.

64. Sasso R.C., Shively K.D., Reilly T.M. Transvertebral transsacral strut grafting for high-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis L5-S1 with fibular allograft. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21(5):328-333.

65. Rodriguez-Olaverri J.C., Zimick N.C., Merola A., et al. Comparing the clinical and radiological outcomes of pedicular transvertebral screw fixation of the lumbosacral spine in spondylolisthesis versus unilateral transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) with posterior fixation using anterior cages. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(18):1977-1981.

66. Gaines R.W. L5 vertebrectomy for the surgical treatment of spondyloptosis: thirty cases in 25 years. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(Suppl 6):S66-S70.

67. Kalra K., Kohli S., Dhar S. A modified Gaines procedure for spondyloptosis. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 2010;92(11):1589-1591.

68. Mehdian S.H., Arun R. A new three stage spinal shortening procedure for reduction of severe adolescent isthmic spondylolisthesis: a case series with medium to long term follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36(11):E705-E711.

69. Santiago-Pérez S., Nevado-Estévez R., Aguirre-Arribas J., Pérez-Conde M.C. Neurophysiological monitoring of lumbosacral spinal roots during spinal surgery: continuous intraoperative electromyography (EMG). Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;47(7-8):361-367.

70. Tosteson A.N., Lurie J.D., Tosteson T.D., et al. Surgical treatment of spinal stenosis with and without degenerative spondylolisthesis: cost-effectiveness after 2 years. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(12):845-853.

71. Interspinous process decompression (IPD) system (XSTOP) for the treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis. Surg Technol Int. 2006;15:265-275.

72. Gudavalli M.R., Cambron J.A., McGregor M., et al. A randomized clinical trial and subgroup analysis to compare flexion-distraction with active exercise for chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(7):1070-1082.

73. Fayyazi A.H., Ordway N.R., Park S.A., et al. Radiostereometric analysis of postoperative motion after application of Dynesys dynamic posterior stabilization system for treatment of degenerative spondylolisthesis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2010;23(4):236-241.

74. Schwarzenbach O., Berlemann U. Dynamic posterior stabilization with the pedicle screw system DYNESYS®. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2010;22(5–6):545-557.

75. Siepe C.J., Heider F., Beisse R., Mayer H.M., Korge A. Treatment of dynamic spinal canal stenosis with an interspinous spacer. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2010;22(5–6):524-535.

76. Lee S.H., Lee J.H., Hong S.W., et al. Factors affecting clinical outcomes in treating patient with grade 1 degenerative spondylolisthesis using interspinous soft stabilization with a tension band system: a minimum 5-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). April 19, 2011. [Epub ahead of print]

77. Marotta N., Cosar M., Pimenta L., Khoo L.T. A novel minimally invasive presacral approach and instrumentation technique for anterior L5-S1 intervertebral discectomy and fusion: technical description and case presentations. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;20(1):E9.

78. Aryan H.E., Newman C.B., Gold J.J., et al. Percutaneous axial lumbar interbody fusion (AxiaLIF) of the L5-S1 segment: initial clinical and radiographic experience. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2008;51(4):225-230.

79. Sharma A.K., Kepler C.K., Girardi F.P., et al. Lateral lumbar interbody fusion: clinical and radiographic outcomes at 1 year: a preliminary report. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2011;24(4):242-250.

80. Youssef J.A., McAfee P.C., Patty C.A., et al. Minimally invasive surgery: lateral approach interbody fusion: results and review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35(Suppl 26):S302-S311.

81. Oliveira L., Marchi L., Coutinho E., Pimenta L. A radiographic assessment of the ability of the extreme lateral interbody fusion procedure to indirectly decompress the neural elements. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35(Suppl 26):S331-S337.

82. Williams B.J., Sansur C.A., Smith J.S., et al. Incidence of unintended durotomy in spine surgery based on 108,478 cases. Neurosurgery. 2011;68(1):117-123. discussion 123–124

83. Park P., Garton H.J., Gala V.C., Hoff J.T., McGillicuddy J.E. Adjacent segment disease after lumbar or lumbosacral fusion: review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29(17):1938-1944.

84. Liao J.C., Chen W.J., Chen L.H., et al. Surgical outcomes of degenerative spondylolisthesis with L5-S1 disc degeneration: comparison between lumbar floating fusion and lumbosacral fusion at a minimum five-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36(19):1600-1607.