14 Spinal Stenosis Without Spondylolisthesis

KEY POINTS

Aging in the lumbar spine is most commonly manifested in the form of spinal stenosis, which is referred to as degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. With the advances in medicine extending life spans, degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis is likely to be an ever-increasing problem. Spinal stenosis was first described over 50 years ago by Verbiest as a radicular syndrome from developmental narrowing of the lumbar vertebral canal.1

Clinical Case Example

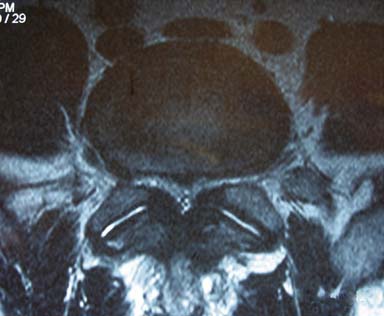

A 60-year-old man presents with progressive back and leg pain that is worse with standing and walking. On further discussion the patient admits to decreasing ability to walk for longer than 10 minutes, and he feels relief with sitting. The patient answers positively when asked if he can walk longer if he leans forward on a grocery cart. The patient admits to prior physical therapy and epidural steroid injections without relief. On examination the patient has a normal gait, with positive distal pulses at 70 beats per minute and no cyanosis or edema in the lower extremities. His reflexes are rated 2/4; strength is rated 5/5; he exhibits negative straight leg raise, no radiculopathy, and no myelopathy with no focal neurological deficits. Review of his T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) axial images of the lumbar spine demonstrates significant stenosis at the L4-L5 level secondary to hypertrophied ligamentum flavum and facet hypertrophy (Figure 14-1).

Basic Science

The pathogenesis of lumbar stenosis is an interesting degenerative cascade that eventually leads to the pathognomonic signs and symptoms. In brief, the degenerative cascade begins at the level of the intervertebral disc, which consists of an inner nuclear core called the nucleus pulposus and an outer supporting layer of the disc called the annulus fibrosus. Beginning early in life, the nucleus pulposus loses its vascular supply and depends on diffusion for its nutrient base, which slowly becomes insufficient. This change in vascular supply leads to dehydration and altered proteoglycan matrix, thus altering the mechanical properties of the disc and the pressure distribution within the disc and leading to a stressed and bulging annulus with loss of disc height.2

Vascular regression within the disc is thought to occur as the child moves from quadrupedal to bipedal motion, thus increasing the load on the disc space in the vertical position. The increasing intradisc pressure leads to involution of the blood supply. By 4 years of age the disc largely depends on cellular diffusion for survival.2 With increasing age the metabolic strain to the intervertebral disc increases, yet the vascular supply is insufficient and diffusion cannot maintain the demands. The altered metabolism in the disc changes the overall electrolyte balance in the disc space, decreasing the net inward flow of fluid and decreasing water content from 90% to 70%; this change ultimately leads to loss of disc height and expandability.2

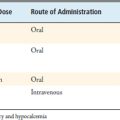

The aforementioned degeneration of the intervertebral disc leads to altered local and segmental mechanics, generating a cascade of compensatory changes within the facet complex, bones, and ligaments.2 Along with degenerative changes occurring with the normal aging spine, the surrounding support structures are also aging and thus degenerating. The most important of the surrounding structures are the core muscles, which include the paraspinal musculature and the abdominal muscles.3 As these supporting muscles lose tone, the spinal column stability depends more on the facet joints, ligaments, and intervertebral discs leading to compensatory hypertrophy of the ligaments, hypertrophied facet joints, and calcified annular-vertebral osteophytes (Table 14-1).3

TABLE 14-1 The Basic Degenerative Cascade for Lumbar Stenosis

Each patient develops unique symptoms based on his or her particular pathology, but in general, this degenerative process leads to central stenosis, foraminal stenosis, or both.3 The most common levels affected are L4-L5 followed by L3-L4.

Recent histological and biochemical studies were performed to assess the pathomechanism of ligamentum flavum hypertrophy in degenerative spinal stenosis.4 In 2005, Saiyro et al analyzed 308 specimens of ligamentum flavum from patients with spinal stenosis and concluded that fibrosis of the ligamentum flavum was the primary cause of the hypertrophy, and the fibrosis is a result of the mechanical stresses occurring with the degenerative cascade. The authors found high levels of transforming growth factor (TGF) and concluded that endothelial release of TGF in the early stages of degeneration may lead to the initial ligamentum flavum hypertrophy.4 In 2007, Saiyro et al examined the amount of elastic fibers versus fibrosis or “scar tissue” in 21 ligamentum flavum specimens retrieved from patients with lumbar stenosis and compared them to normal controls. The authors found a significant amount of fibrosis in the ligamentum flavum from patients with stenosis and concluded that fibrosis or “scarring” causes hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum.5

The spinal canal dimensions are not constant and are influenced by dynamic and postural factors.3 Axial loading of the intervertebral disc causes bulging of the annulus, which in turn further compromises the central canal and the foramen. There can also be osteophyte formation from a degenerated facet joint, which can induce lateral recess or foraminal stenosis.3

Degeneration and aging is ubiquitous in the human, and the lumbar spine is not exempt. Degeneration is manifested as osteoarthritis in the lumbar spine and is largely responsible for the high prevalence of low back pain in the population; however, the resulting spinal stenosis is not totally responsible for “back pain” in the human population. In general, any patient in the seventh decade of life will exhibit radiographic evidence of spinal stenosis, but only a small percentage of these patients ever suffer from the symptoms of spinal stenosis.6

As previously discussed, degeneration is part of the life cycle and degeneration in the lumbar spine begins very early in life, with loss of the vascular supply to the intervertebral discs, and subsequent radiographic degenerative changes follow. Boden et al examined 67 individuals without back pain, neurogenic claudication, or radiculopathy.7 Of the patients examined, 20% of the patients younger than 60 years had MRI evidence of herniated discs or stenosis. In the group of patients older than 60 years, 57% demonstrated degenerative changes including herniated discs and spinal stenosis. In fact there was radiographic evidence of degenerative disc disease in 35% of patients younger than 40 years, and in over 99% of the subjects older than 60 years. Thus, in our practice we follow the philosophy of “never treat films, treat the patient,” which is particularly applicable when dealing with degenerative lumbar stenosis.

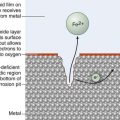

The classic pathognomonic symptom complex for lumbar spinal stenosis is termed “neurogenic claudication.” In brief, patients with spinal stenosis will not suffer or exhibit symptoms while sitting or at rest. Once a patient stands or begins walking, they will begin to sense a heaviness or aching in their lower extremities, or both, which is relieved with sitting. Patients will inherently discover that if they maintain a slightly flexed posture in the lumbar spine, they can walk farther because the central canal and foraminal space is opened with flexion; for example, when leaning on the grocery cart while shopping. As the stenosis progressively worsens, the patients lose the ability to walk several feet or even stand upright. Symptoms may vary depending on whether the patient is suffering central canal stenosis or foraminal stenosis or both. Neurogenic claudication and radiculopathy secondary to spinal stenosis can basically be attributed to either direct mechanical compression from hypertrophied ligamentum flavum, bulging discs, and so on, or indirect vascular insufficiency from inadequate oxygen delivery to the nerve roots.8 Upon standing vertically, the lumbar lordotic angle increases, thus increasing the degree of stenosis by inducing an inward buckling of the hypertrophied ligamentum flavum into the central canal or lateral recess. This compression may act directly on neural elements or on the neurovascular supply.3 The venous congestion is highly visible in some patients at the time of surgery. Whereas in the sitting position, the lordotic angle decreases, allowing the ligamentum flavum to relax, opening the canal and lateral recess and allowing adequate oxygen delivery.

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Surgery

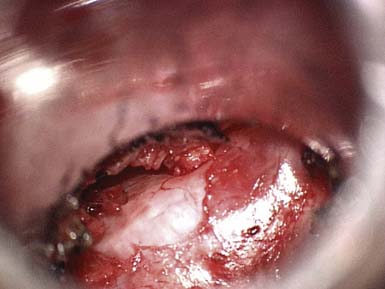

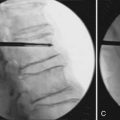

Decompressive lumbar laminectomy has been the classic approach for the treatment of spinal stenosis. Numerous surgical techniques have subsequently been developed since the advent of the classic open approach, including but not limited to minimally invasive surgeries. Rahman et al9 compared multiple variables in patients who underwent “classic” open decompressive lumbar laminectomy versus minimally invasive surgery (MIS) for lumbar decompression. The MIS approach allowed for bilateral decompression through a unilateral dilator and use of the microscope (Figures 14-2 and 14-3). Results demonstrated that MIS patients had shorter operating room times, less blood loss, shorter length of hospital stay, and fewer complications. In addition, the MIS patients had better mobility in the immediate postoperative period.

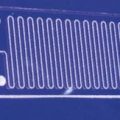

One of the newer MIS techniques is the “interspinous process spreader,” which is currently on the market and in development by several companies worldwide.10 In simplistic terms, the devices are designed to be placed between the lumbar spinous processes and force the spinous process into a flexed posture, thus indirectly decompressing the spinal canal. Siddiqui et al analyzed the one-year outcomes after placing an interspinous process spreader in 40 patients with spinal stenosis and found that 54% of patients reported clinically significant improvement in their symptoms, 33% reported improvement in function, and 71% expressed satisfaction with the surgery.10

1. Verbiest H. A radicular syndrome from developmental narrowing of the lumbae vertebral canal. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1954;36:230-237.

2. Dickerman R.D., Zigler J.E: Discogenic Back Pain. In Spivak J.M., Connolly P.J., editors, 3rd eds, Orthopaedic Knowledge Update Spine, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Rosemont, IL, pp 319-329, 2005.

3. Epstein N.E: Lumbar spinal stenosis. In Winn H.R., editor, 5th eds, Youmans neurological surgery, Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, pp 4521-4539, 2005.

4. Sairyo K., Biyani A., Goel V. Pathomechanism of ligamentum flavum hypertrophy: a multidisciplinary investigation based on clinical, biomechanical, histologic, and biologic assessments. Spine. 2005;30:2649-2656.

5. Sairyo K., Bivani A., Goel V.K. Lumbar ligamentum flavum hypertrophy is due to accumulation of inflammation-related scar tissue. Spine. 2007;32:340-347.

6. Healy J.F., Healy B.B., Wong W.H. Cervical and lumbar MRI in asymptomatic older male lifelong athletes frequency of degenerative findings. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 1996;20:107-112.

7. Boden S.D., Davis D.O., Dina T.S. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 72, 1990. 403–208

8. Watanabe R., Parke W.W. Vascular and neural pathology of lumbosacral spinal stenosis. J. Neurosurg. 1986;64:64-70.

9. Rahman M., Summers L.E., Richter B. Comparison of techniques for decompressive lumbar laminectomy: the minimally invasive versus the “classic” open approach. Minim. Invasive Neurosurg. 2008;51:100-105.

10. Siddiqui M., Smith F.W., Wardlaw D. One-year results of XStop interspinous implant for the treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 2007;32:1345-1348.