15 Spinal Stenosis with Spondylolisthesis

KEY POINTS

Spinal stenosis accompanied by spondylolisthesis is a common diagnosis encountered by the spinal surgeon. Although nonoperative treatment consisting of antiinflammatory medications and epidural steroid injections is effective in some patients, many patients with severe symptoms are not helped by this strategy.1,2 In the group that fails conservative therapy, decompression has been shown to be an effective treatment modality.2–4 Although numerous studies have clearly demonstrated the beneficial effects of decompressive laminectomy, the fear of creating instability often limits this procedure’s application. The concomitant presence of spondylolisthesis increases this likelihood. Controversy also persists regarding the virtues of concomitant spinal fusion in this patient population, which is often elderly. When fusion is chosen, the decision of whether or not to use instrumentation must be made. Fortunately, the management of this condition has evolved over the past several decades and numerous prospective randomized trials have been performed assessing the influence of fusion and instrumentation following decompression.

Part One: Understanding the Condition

Pathophysiology

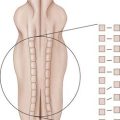

As the spine ages, the accumulation of years of axial loading and rotational strains may lead to disc degeneration, facet arthrosis with hypertrophy, thickening or buckling of ligamentum flavum, and osteophyte formation. This cascade of degenerative changes can result in the development of central canal or foraminal narrowing with resulting neural compression characterized by low back, buttock, and lower extremity pain.1 They can also result in varying degrees of spinal instability and, depending on the anatomic predisposing factors, the vertebra develops either anterolisthesis or retrolisthesis. Spondylolisthesis, the slippage of one vertebra relative to the adjacent vertebrae, often results from asymmetric degeneration of the disc, the facet joints, or both.

Natural History

The majority of patients with a history of significant neurogenic claudication or vesicorectal symptoms have been shown to have poor outcomes without intervention. A prospective observational cohort study assessing the long-term outcomes (8- to 10-year follow-up) of patients with lumbar spinal stenosis treated either surgically or nonsurgically has demonstrated increased leg pain relief and greater back-related functional status in patients who initially received surgical treatment. Although degenerative spondylolisthesis has been shown to progress in 25% to 30% of patients, it fortunately rarely progresses to more than 30% of the subjacent vertebra. Some studies have demonstrated that as the pathology progresses and the disc space collapses, back pain can improve spontaneously.

Part Two: Clinical Decision Making

Specific Patient Populations and Situations

Elderly

Some controversy exists as to whether age should be considered an independent risk factor for surgery. Many authors report no difference in outcome or rate of complications between elderly and younger patients of comparable health.7 Therefore advanced age alone should not be a contraindication for surgery. Some studies, on the other hand, have demonstrated that increasing age can be an independent risk factor for surgery, especially if the patient is older than 60 years.5 One such study noted a 41% complication rate (14% major and 27% minor) for patients 41 to 60 years of age and a 64% complication rate (24% major and 40% minor) for those 61 to 85 years of age (27). Pulmonary complications were the most common major complications and genitourinary problems were the most common minor complications. Age more than 60 years was therefore found to be a significant risk factor for perioperative complication.

It has also been reported that decompressive surgery in the elderly population can be effective without the need for supplemental fusion, and many authors therefore do not recommend fusion in patients older than 70 years. This is partly because the risk of developing postoperative instability in this age group appears to be small because of some intrinsic stability afforded by the spondylosis and spondylarthrosis that occur as the spine ages as well as the decreased activity level of this population.5

Multiple Comorbidities

Patients who have multiple comorbidities, such as cardiac disease, vascular disease, or diabetes have an increased risk for postoperative complications.6,7 The preoperative evaluation and optimization of patients with these conditions is critical. The addition of an arthrodesis increases the length of anesthesia as well as the amount of blood loss. Both of these factors can delay recovery time, and patients with multiple comorbidities are therefore more likely to require an extended rehabilitation period. These factors should all be considered when deciding upon the advisability of supplemental fusion with decompression. Finally, for patients with a limited life expectancy, treatment should be focused on obtaining an immediate improvement in quality of life without subjecting the patient to a prolonged and painful recovery period.

Several studies in the literature have examined the relationship between preoperative comorbidities and postoperative complications. Although there is a link between certain risk factors and postoperative mortality, increasing American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) physical status class has been shown to be one of the best independent predictors of mortality. Previous studies have reported an increasing rate of postsurgical mortality with increase in the ASA class. In fact, increasing morbidity and mortality rates have been prospectively demonstrated with an increase in the ASA class in a large population where the mortality rate increased from zero to 7.2% from ASA class 1 to ASA class 4, respectively.7

Osteoporosis

Osteoporotic bone is a relative contraindication to instrumented fusion because of the difficulty in obtaining and maintaining adequate fixation at the bone–screw interface. Although variations in technique such as the use of larger diameter screws, screw threads with more aggressive pitch to improve pull-out strength, and augmentation of the bone–screw interface with methylmethacrylate have been advocated, failures of fixation are still likely.6

Indications for Fusion

The indications for surgical management are persistent or recurrent back pain with leg pain or neurogenic claudication, leading to a significant reduction in quality of life, despite a reasonable trial of nonsurgical treatment (>3 months); progressive neurologic deficit; and bladder or bowel symptoms resulting from neurologic compression.5 Surgical options vary from decompression alone to fusion with or without instrumentation. More recent additions to the surgical armamentarium include ligament stabilizers and biologic agents. There continues to be a tremendous amount of controversy regarding the efficacy of fusion in degenerative disease resulting in low back pain (LBP).8,9

Concomitant de Novo Scoliosis—Significant Curve and Progressing Curve

When nonoperative management of patients with this combination of pathologies fails, decompressive procedures are often required. Patients with DDS who undergo laminectomy commonly require concomitant fusion since removal of the posterior elements can compromise spinal stability. In addition, the traditional aim of surgery is to both decompress the compromised neural elements and to create a balanced and stable spine in both the coronal and sagittal planes. As with other conditions, the surgical morbidity of DDS is significantly greater when the decompressive surgery is combined with fusion.5,6

Part Three: Management

Nonsurgical

As with the majority of spinal disorders, it is appropriate to attempt a nonsurgical solution first. Most patients with symptomatic spinal stenosis and degenerative spondylolisthesis respond to nonsurgical management and do not require surgery. Conservative treatments for spinal stenosis with degenerative spondylolisthesis include nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, membrane stabilizer medications (e.g., gabapentin, pregabalin), activity modification, and physical therapy.10

The mainstay of physical therapy for this condition emphasizes flexion exercises, back strengthening, and aerobic conditioning. Aerobic conditioning can be somewhat problematic in this population, but exercises performed in flexion, such as stationary bicycle, enlarge the neural foramen and central canal, minimizing the symptoms of neurogenic claudication. Passive modalities such as ultrasound, massage, heat, and spinal manipulation are useful in that they may temporarily improve symptoms, but their efficacy has not been verified by prospective studies with long-term follow-up.10

Surgical

Fusion Options with or without Instrumentation

Although surgical decompression alone often improves symptoms in the patient with spinal stenosis and degenerative spondylolisthesis, numerous studies have demonstrated the benefits of concomitant fusion, either noninstrumented or instrumented.4,5,11 For stabilizing the spine, instrumented fusions are superior to uninstrumented fusions. However, they are not always feasible, especially in the elderly population with osteoporotic bones. When a fusion is desired but instrumentation is contraindicated, the benefit of noninstrumented fusions are that they generally require less dissection and blood loss and require less surgical time under anesthesia.

Decompression and Noninstrumented Posterolateral Fusion

Concomitant fusion improves long-term outcomes when a decompressive laminectomy is performed for spinal stenosis with degenerative spondylolisthesis. The placement of instrumentation increases morbidity, as well. It seems logical that un-instrumented posterolateral fusion could provide a good compromise between the two options.9 Though much of the morbidity associated with preparation of the fusion bed would remain (increased dissection and pain, increased anesthesia time, and blood loss), the additional trauma and time of instrumentation placement would be avoided. Prospective studies of patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis who underwent decompression and uninstrumented dorsolateral fusion versus patients undergoing decompression alone have in fact demonstrated significantly better outcomes. Of note, although this procedure is associated with a high pseudoarthrosis rate (up to 36%), this did not affect patient outcomes. This is thought to be the result of stiffening of the spine and motion restriction due to a stable pseudarthrosis.11,12

Fusion with Biologics

A second prospective randomized clinical study has evaluated the use of rhBMP-2 to achieve posterolateral spine fusion in patients with a grade I spondylolisthesis and single level degenerative disc disease that were scheduled to undergo single level posterolateral lumbar arthrodesis. The study compared patients undergoing autogenous iliac crest bone graft with pedicle screw instrumentation, rhBMP-2 with pedicle screw instrumentation, and rhBMP-2 only with no instrumentation. The study demonstrated a radiographic fusion rate of 40% in the autogenous iliac crest bone graft with pedicle screw instrumentation, 100% in patients that received rhBMP-2 with pedicle screw instrumentation, and 100% in the rhBMP-2–only group.13 More importantly, the clinical outcomes improved faster and to a greater degree in the rhBMP-2–only group. The surgical time was significantly less secondary to the elimination of the time required for bone graft harvest and placement of internal fixation.

Decompression and Posterolateral Fusion with Instrumentation

The most effective method of achieving “stability” following decompression is the addition of instrumentation.11 A prospective randomized study comparing the results of decompression and arthrodesis alone with those of decompression and arthrodesis combined with instrumentation has shown that the addition of spinal instrumentation improved the fusion rate (82%, instrumented versus 45%, noninstrumented).4 Although achieving a solid fusion appeared to be less important, since no significant difference was found in clinical outcomes, more recent longer term (5- to 14-year) follow-up studies have reported that patients with pseudarthrosis did not do as well as those that achieved solid fusion.4,11 The complication rates, revision rates, radiographic results, and patient satisfaction at 5-year follow-up were reviewed for patients following segmental posterior instrumented fusion with decompression in patients with lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis and showed that no patient had a neurologic deficit, evidence of symptomatic pseudarthrosis (i.e., pain, lucency, loose instrumentation), or recurrent stenosis at the fused segment.7

Unfortunately, posterolateral fusion requires a large dissection for the preparation of the fusion bed, which is associated with increased pain, bleeding, time in surgery, and recovery. In addition to this, instrumentation further increases the morbidity of the surgery.12

Nonfusion Options

Laminectomy

Many studies have demonstrated the efficacy of dorsal decompression for alleviating the symptoms of spinal stenosis.1–3 Although laminectomy is a relatively well-tolerated procedure, the incidence of postoperative instability (increased translation and loss of alignment) has been reported to be as high as 50% in patients undergoing laminectomy for spinal stenosis and even higher in patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis.5,10

When performed properly, the risk of postoperative instability following this procedure is less than 2% in patients without degenerative scoliosis. The risk of instability increases in patients with degenerative scoliosis, especially as the magnitude of the curve increases. Patients with curves greater than 20 degrees are at a higher risk of curve progression and often require prophylactic fusion. The risk of worsening postoperative spondylolisthesis also increases with the number of levels decompressed, ranging from 6% for 2 levels to 15% for 3 or more levels.

Conclusion

When decompressive procedures are performed without fusion, a radical decompression should be avoided at the base or apex of a curve in order to minimize risk of curve progression. Curves that are greater than 20 degrees, demonstrate progressive deformity, or fit both criteria, are not good candidates for decompression without fusion. Finally, patients with significant axial pain are less likely to experience improvement in their back pain without concomitant fusion. Recent short-term studies have also shown the efficacy of adding biologics to aid in obtaining a solid fusion. Future technologies, such as dynamic stabilization and interspinous distraction devices, will require long-term prospective studies to prove their role in managing the patient with degenerative scoliosis and spondylolisthesis.

1. Sengupta D.K., Herkowitz H.N. Lumbar spinal stenosis. Treatment strategies and indications for surgery. Orthop. Clin. North Am.. 2003;34:281.

2. Katz J.N., Lipson S.J., Larson M.G., et al. The outcome of decompressive laminectomy for degenerative lumbar stenosis. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am.. 1991;73:809.

3. Caputy A.J., Luessenhop A.J. Long-term evaluation of decompressive surgery for degenerative lumbar stenosis. J. Neurosurg.. 1992;77:669.

4. Bridwell K.H., Sedgewick T.A., O’Brien M.F., et al. The role of fusion and instrumentation in the treatment of degenerative spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis. J. Spinal Disord.. 1993;6:461.

5. Matsunaga S., Ijiri K., Hayashi K. Nonsurgically managed patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis: a 10- to 18-year follow-up study. J. Neurosurg.. 2000;93:194.

6. Benz R.J., Ibrahim Z.G., Afshar P., et al. Predicting complications in elderly patients undergoing lumbar decompression. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res.. 2001:116.

7. Wang M.Y., Green B.A., Shah S., et al. Complications associated with lumbar stenosis surgery in patients older than 75 years of age. Neurosurg. Focus. 2003;14:e7.

8. Fischgrund J.S. The argument for instrumented decompressive posterolateral fusion for patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis and spinal stenosis. Spine. 2004;29:173.

9. Phillips F.M. The argument for noninstrumented posterolateral fusion for patients with spinal stenosis and degenerative spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2004;29:170.

10. Murphy D.R., Hurwitz E.L., Gregory A.A., Clary R. A non-surgical approach to the management of lumbar spinal stenosis: a prospective observational cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord.. 2006;7:16.

11. Kornblum M.B., Fischgrund J.S., Herkowitz H.N., et al. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis: a prospective long-term study comparing fusion and pseudarthrosis. Spine. 2004;29:726.

12. Ghogawala Z., Benzel E.C., Amin-Hanjani S., et al. Prospective outcomes evaluation after decompression with or without instrumented fusion for lumbar stenosis and degenerative Grade I spondylolisthesis. J Neurosurg Spine. 2004;1:267.

13. Boden S., Kang J., Sandhu H., et al. Use of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 to achieve posterolateral lumbar spine fusion in humans: A prospective, randomized clinical pilot trial 2002 Volvo Award in clinical studies. Spine. 2002;27:2662.