Chapter 129 Spinal Cord Stimulation and Intraspinal Infusions for Pain∗

The first clinical report of spinal cord stimulation (SCS) was published in 1967.1 Since then, the use of implantable devices for the management of chronic pain has become well established in the United States, Europe, and Australia. Electrical stimulation of the spinal cord has proven efficacy for the relief of pain in patients with arachnoiditis, pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (PVOD), peripheral nerve injury, complex regional pain syndrome, angina pectoris, and radiculopathy and pain of spinal origin.

General indications for SCS implantation can be applied to all potential candidates. It is usually accepted, but not proven, that patients who have objective findings related to their pain complaint will have better outcomes after implantation than patients who do not have such evidence. A clear exception to this rule is patients with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) for whom there is often not objective evidence of their pain complaint but who have been reported to respond well to SCS.2

The final general indication for implantation is response to a trial of SCS. A survey of academic pain centers in the United States reveals that all respondents indicated that trials are done before implantation.3 The average duration of a trial for spinal cord stimulation is 6.6 days. Two programs report that trials for SCS are done on the day of implantation in the operating room. Although some practitioners may believe that this is an inadequate trial, there is no evidence to compare duration of trial and outcome for SCS. There is general consensus that a trial of approximately 1 week with good pain relief is the best predictor of success with subsequent implantation.

Cost-effectiveness analysis of SCS versus best medical and conventional treatment for chronic pain shows that the cumulative 5-year costs for SCS were $29,123 per patient compared with $38,029 for patients treated with conventional methods.4 In addition, 15% of patients on SCS returned to work compared with none of the patients in the conventional care group. A lifetime cost analysis of SCS versus costs and outcomes before SCS in patients with CRPS showed not only decreased pain and improved quality of life but a savings of $60,000 per patient.5 Similar outcomes were obtained when comparing patients treated for intractable angina pectoris with and without SCS.6,7

Mechanism of Action and Device Characteristics

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulators are believed to reduce pain by stimulating large myelinated afferent nociceptive fibers in the periphery. This increase in large-fiber activity theoretically stimulates inhibitory interneurons in the substantia gelatinosa, thereby “closing the gate” on the transmission of painful information carried on small fibers. The first SCS implantation was performed based on this theory. This theory has been criticized based on the facts that only chronic, and not acute pain, is reduced by SCS; SCS works for neuropathic pain but not consistently for somatic pain (except for ischemic pain in peripheral vascular disease and angina pectoris, which cannot be characterized as neuropathic); paresthesias must overlap the painful area; several minutes are required before pain is suppressed; weeks of stimulation may be needed to reach maximal pain relief; and relief may outlast stimulation by long periods of time.8 Pain relief cannot be explained based solely on the “gate control theory” of pain. The SCS mechanism of action is unclear. Some support can be found for 10 different specific mechanisms or proposed mechanisms of action, and the reader is referred for further discussion to a recent review by Oakley and Prager.8

Improvement of equipment has increased efficacy and decreased the complication rates for implanted SCS systems. Complication rates have declined to approximately 8%, and reoperation rates may be as low as 4%.9 Early SCS systems employed a single monopolar electrode that connected to a percutaneous externalized power source. The standard of care today involves implanted electrodes that are typically quadripolar but that can have dual octapolar electrodes. The number of potentially usable electrode combinations in a dual octapolar system is in the tens of millions. Programming of such a stimulator has not evolved to a point where one can select from among all these combinations, but supporters contend that the large numbers of possible combinations, the closer proximity of electrodes, and the longer area of possible coverage improve the success rate and quality of relief.

Indications and Specific Selection Criteria

The most common indication for SCS in the United States is for back or neck radiculopathic pain. Patients presenting with conditions such as lumbar or cervical radiculopathy, postlaminectomy syndrome, spondylolisthesis, spondylosis, or even persistent and refractory axial low back pain of uncertain etiology may respond to treatment with SCS and should be assessed. Topography of pain that is amenable to overlap by paresthesia of the spinal cord stimulating device is a requirement for successful treatment.10 Radicular patterns tend to be more easily obtained than axial patterns, and for this reason, patients with pain predominantly in the extremities may be better candidates than patients with predominantly axial symptoms. This should not exclude a trial in an otherwise good candidate who has primarily axial symptoms. Although it is technically more difficult to obtain coverage of patients with predominantly axial back or neck pain, newer, more compact electrodes with multiple arrays sometimes placed bilaterally and triangularly might be useful in providing relief to patients with axial pain, and these arrays should be considered. Long-lasting relief is a reasonable goal. A large series of patients with follow-up of 2 to 20 years demonstrated that 52% of patients continued to have a 50% reduction in pain.11 The authors noted that even among patients who did not claim a 50% reduction of pain, most patients continued to use their devices.

The evidence of efficacy of SCS for back and neck pain is not lacking. A literature review was performed on studies of patients with SCS for chronic leg and back pain and included all relevant articles identified through MEDLINE search from 1966 through 1994.12 Fifty-nine percent of patients reported in these studies had greater than 50% pain relief at a time between 1 and 45 months after surgery. These authors noted the lack of a randomized trial at that time. Subsequent to this, a prospective, randomized comparison of SCS and reoperation in patients with persistent radicular pain with or without low back pain after lumbosacral spine surgery was conducted.13 The primary outcome measure of this study was frequency of crossover to the alternative procedure. This study showed a statistically significant advantage of SCS over reoperation. A literature review on SCS for chronic pain of spinal origin was conducted by North and Wetzel,9 who concluded that SCS is a valuable treatment option, particularly for patients with chronic pain of predominantly neuropathic origin and a topographic distribution involving predominantly the extremities. Efficacy may be better for spontaneous than for evoked pain.14

Pain associated with spinal cord injury has been treated with SCS. Most authors report satisfactory responses in a smaller percentage of their patients ranging between 20% and 40%.15 Case reports supporting the use of SCS for whiplash and idiopathic acute transverse myelitis have been published.16,17 Sindou and colleagues18 reported the predictive value of somatosensory-evoked potentials assessing neural conduction in the dorsal columns. These authors suggest that if central conduction time is abolished or significantly altered, then the success rate of SCS is dramatically less than in patients with normal preoperative central conduction times.

The usefulness of SCS for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia has recently been described. A prospective case series involving 28 patients with either acute herpes zoster or postherpetic neuralgia were studied over 29 months. Eighty-two percent of patients with intractable pain for longer than 2 years had a median decrease in their visual analogue scale score from 9 to 1 (0 to 10 scale) as well as improvement in their pain disability index. Four patients with acute herpes zoster had prompt and dramatic improvement in their pain symptoms.19

The treatment of PVOD with SCS is the most common indication for this modality in Europe. For no other indication is the early evidence of efficacy more compelling and yet SCS for PVOD is not a common treatment in the United States. One study reported 37 patients receiving adequate pain relief after a trial in 41 patients with end-stage peripheral vascular disease.20 Seventy-eight percent of patients reported substantial pain relief at a mean follow-up of 25 months. Another investigator reported the results of SCS in 20 patients with ischemic rest pain and ulcers.21 Eighteen of 20 patients in this study had immediate relief of pain after electrical stimulation. These authors also reported improved skin nutritional flow leading to healing of ulcers of moderate size and increased salvage of feet with limb-threatening ischemia at 2-year follow-up. They report an increase in capillary density and an increase in red blood cell velocity and peak red blood cell velocity after arterial occlusion by intravital capillary microscopy.

More recently, SCS has been investigated by the European Peripheral Vascular Disease Outcome Study.22 Patients with nonreconstructable critical leg ischemia showed increased limb survival when compared with patients receiving usual treatment without SCS as well as improved pain relief. Patients with transcutaneous oxygen pressure measurement of 10 to 30 mm Hg before SCS trial or if less than 10 mm Hg, an improvement to 20 mm Hg or more during the SCS trial received an implant. Limb amputations were 20% at 12 months in the SCS group compared with 46% in the matched no SCS group. These and other authors suggest the routine use of transcutaneous oxygen pressure both before and during the trial phase as a predictor of success.23 A useful predictor of success in patients with diabetes with PVOD is the absence of autonomic neuropathy.24 Twenty-five of 28 patients with autonomic neuropathy failed SCS treatment, whereas all 32 patients without autonomic neuropathy had successful outcomes.

Evidence exists of the efficacy of SCS in severe Raynaud’s phenomenon25 and Buerger’s disease.26 SCS has shown remarkable effectiveness and should be considered as a treatment for patients with severe PVOD that is not amenable to surgical intervention.

Despite the lack of an identifiable objective lesion, SCS appears to be quite effective for treatment of CRPS. One report retrospectively reviewed experience with SCS and found 12 patients with CRPS who were followed up for an average of 41 months after implantation.27 Eight of these patients reported excellent pain relief, and four patients reported good pain relief. Another study looked at 18 patients with CRPS.28 Fourteen patients had a successful trial and subsequently had their systems internalized. Follow-up varied from 4 to 14 months. Six of 14 patients had good pain relief. Five had moderate pain relief. One had minimal and three had no pain relief. Of note is that pain relief was limited to the body parts covered by the paresthesia.

In a randomized trial comparing SCS plus physical therapy with physical therapy alone in 54 patients with CRPS, the SCS group had a mean reduction in pain of 2.4 cm (on a 1- to 10-cm scale) compared with an increase of 0.2 cm in the physical therapy alone group.2 Health-related quality of life also improved in the SCS group, but, interestingly, there was no difference between the groups in functional status.

A recent report has demonstrated that response to sympathetic blockade can be predictive of a better outcome from SCS for patients with CRPS.29 Thirteen of 13 patients with a positive response to sympathetic blockade had pain relief during the trial period, and 87% had greater than a 50% reduction in pain at 9 months. Only 3 of 10 patients with a negative response to sympathetic blockade had good relief and went on to permanent implantation, and only 33% had a 50% reduction in pain at 9 months.

The treatment of postamputation phantom or residual limb pain with SCS is still a controversial area. Contradictory reports for this and for brachial plexus avulsion injury pain exist, and it is not possible to make definitive recommendations for treating or not treating phantom limb or brachial plexus avulsion injury pain with SCS based on these data.

A large body of data supports the use of SCS for intractable angina pectoris. The complexity and implications of severe coronary artery disease as an indication for SCS requires discussion. The first published report of the use of SCS for angina was in 1987.30 These investigators described 10 patients with intractable angina in whom SCS devices were implanted, which led to a decrease in the frequency and severity of angina and a major reduction in the use of antianginal medications. Other investigators followed with a report on 10 patients and added bicycle ergometry as a measure of exercise tolerance and showed an increase in work capacity, increased time to angina, decrease in recovery time, and a decrease in the magnitude of ST-segment depression associated with angina.31 By 1991, it was shown that reductions in angina attacks continued over 9 months, and a persistence in increase in rate-pressure product (a measure of the ability of the heart to do work).32 Between 1993 and 1994, results of a randomized, prospective study demonstrated improved exercise capacity, improved quality of life, and a decrease in ischemic episodes as measured by Holter monitor.33–35 Complications were few and of a technical nature, and a surgical algorithm that did not involve a trial before implantation was described. It has been shown that SCS does not conceal myocardial infarction that may occur in patients with implanted devices.36 A decrease in hospital admissions for patients with implanted SCS devices compared with a control group has been demonstrated.37 In 80% of patients, the beneficial effect has been reported to last 1 year, and in 60%, improvement in exercise capacity and quality of life lasted as long as 5 years.38–40 There are no data showing harmful or nontherapeutic effects of SCS for angina. The use of SCS may be beneficial even in critically ill patients. Janfaza and colleagues41 reported the 6-week survival in such a patient, whereas other investigators have reported an effect insufficient to overcome the severity of ischemic disease, albeit relief of ischemic symptoms, until death occurred.42

A prospective, randomized trial of SCS versus coronary artery bypass grafting in 104 patients with severe angina, increased surgical risk, and no prognostic benefits from revascularization demonstrated long-lasting improvement in quality of life and comparable survival and symptom control in both groups.43 Benefit after discontinuation of SCS has been shown for as long as 4 weeks after discontinuation.44 No difference in anginal complaints, nitroglycerin intake, ischemia, or heart rate variability was shown. SCS has been shown to decrease hospitalization in patients with angina,45 and there is evidence that modern SCS devices are compatible with modern pacemaking devices.46,47

Description of Technique

Patients with chronic pain may have central changes that amplify painful signals. It is necessary to have the patient awake and able to answer questions appropriately to assess the location of paresthesia during the trial phase. Patients may require laminectomy for placement of a paddle-type electrode in the thoracic or cervical region. Patients with chronic pain often have multiple comorbidities, particularly patients with PVOD or intractable angina pectoris. These factors create an anesthetic challenge and require a preoperative consultation between surgeon and anesthesiologist to define goals and needs. Our typical anesthetic involves intravenous fentanyl and midazolam for analgesia, anxiolysis, and amnesia and propofol for sedation. The propofol can be turned off, and the patient awakened for questioning regarding paresthesia topography at appropriate intervals. We also use large volumes of local anesthetic, typically 0.5% lidocaine without epinephrine. A dose of 4 mg/kg (56 ml for a 70-kg person) can be safely administered even as a single dose and more can be administered after 1 or 2 hours. Another option is intravenous remifentanil plus local anesthetic, but this requires an anesthesiologist experienced in the use of this drug because the therapeutic window is often so narrow. Despite the best efforts of experienced practitioners, the implanter should be prepared for oversedation and the need for airway control during the procedure or suboptimal ability to describe the paresthesia topography. The patient should be advised that this is a possibility and that if it occurs, the electrode can still be placed without paresthesia guidance, but success rate might be reduced. The patient should also be educated about information needs that will occur intraoperatively before getting to the operating room. A recent report describes the successful implantation of an SCS device in 19 of 19 patients undergoing laminectomy with 12.5- to 20-mg bupivacaine intrathecal spinal anesthesia.48 In all patients with spinals and anesthesia throughout the surgical procedure, SCS paresthesia was readily appreciated by the patients.

There is no description of the absolute need for alertness and ability to communicate during surgery. It is generally accepted that, due to uncertainty about anatomic and physiologic overlap, simply placing the lead at the proper anatomic location will not reliably produce a paresthesia that will be effective in reducing pain. There are published case series in which successful implantation has been done under general anesthesia.49

A retrospective, nonrandomized review of surgical experience concluded that patients with flat electrodes placed via laminectomy had better pain relief that was longer lasting than patients who had percutaneously placed cylindrical electrodes.49 A prospective, randomized, controlled trial has recently shown that electrode arrays implanted via laminectomy had lower amplitude requirements and better patient ratings of paresthesia coverage.50 The decision as to whether to place a flat electrode via minilaminectomy or a percutaneously placed cylindrical electrode is a controversial and emotionally charged issue because anesthesiologists, who place most of these devices, use a percutaneous approach and many neurosurgeons place leads via laminectomy. To further complicate matters, anesthesiologists should not place leads via laminotomy because they do not have the training, experience, or ability to manage complications and many pain specialist anesthesiologists derive substantial income from placing SCS devices. Additionally, other specialists such as physiatrists and neurologists are receiving training and are eligible for board certification in pain medicine and are implanting cylindrical leads. At this time, there is no overwhelming evidence of the advantage of placing electrodes via a laminectomy compared with percutaneously placed leads, but there is at least one compelling study.50

For percutaneous placement of a cylindrical electrode, the procedure is as follows. Patients are placed prone on a fluoroscopy table in the operating room and prepared for a surgical procedure that can last hours. We do not place a Foley catheter. Standard surgical preparation is done after identifying important landmarks fluoroscopically and marking the skin to identify them. The skin and subcutaneous tissue are anesthetized with local anesthetic before insertion of the 15-gauge epidural needle. The epidural space is identified using a loss of resistance to air or saline technique (Fig. 129-1). For a patient with an L5 radiculopathic pain pattern, the epidural space is entered at approximately T12–L1, at which point the cylindrical electrode is advanced through the needle and positioned using fluoroscopic guidance to the desired level at approximately T9–T10, at which time trial stimulation is carried out (Figs. 129-2 and 129-3). For placement of a device for stimulation of the upper extremity, entry is made at T1–T3 with the electrode tip to arrive at C3–T4 approximately. The target site for the electrode tip for a patient with angina is approximately T4–T5. For a unilateral syndrome, the electrode should be positioned approximately 3 mm ipsilaterally off midline. The electrode can be directed and “steered” using an angled stylet. Once the target anatomic site is reached, the electrode is anchored and attached to a temporary screening cable and a trial screener. The awakened patient is then questioned about the presence or absence and location of paresthesia coverage. Parameters that are available for adjustment include amplitude and pulse width and frequency, the same as with an implanted generator.

Once good paresthesia overlap to pain topography is obtained, the electrode is disconnected from the cable. A 5-cm vertical incision over the site of epidural needle placement is made. The subcutaneous tissue is undermined at the level of the lumbodorsal or supraspinous fascia, the epidural needle is carefully removed along with the electrode stylet, and the lead is anchored using an anchoring device that will prevent the electrode from migrating (Fig. 129-4). The electrode is attached to a percutaneous extension lead, and a tunneling device is used to exit the skin at a site approximately 10 cm lateral to the incision. The electrode is placed within the incision with only the temporary connecting cable externalized. This allows the electrode to remain beneath the skin throughout the entire trial period. Care should be taken to avoid contact of the electrocautery device with the electrode. A defect in the electrode could result in a line of continuity between the externalized lead and the epidural space. If the patient has a successful trial, then it is necessary only to remove the extension lead, and the electrode, which has already been positioned and has not been exposed to a contaminated external environment, can remain in place. The skin and subcutaneous tissue are closed with interrupted Vicryl sutures and skin staples.

FIGURE 129-4 The cylindrical electrode is anchored within an undermined incision extending to the dorsolumbar fascia.

Placement of a paddle-type electrode or flat lead is done via a standard laminotomy procedure. The electrode is placed in the epidural space using the same anatomic targets as described for cylindrical electrode placement. A dual laminotomy is sometimes required to properly position the electrode.51 Paresthesia overlap with topography of pain should be tested with the awake patient intraoperatively. The electrode cable is anchored to fascia, and the electrode is attached to a temporary percutaneous connecting wire as described previously.

Intraoperative problems peculiar to SCS implantation include an inability to properly position the electrode in the epidural space, inability to obtain paresthesia overlap of the painful area, and unanticipated events. We have described the inability to thread a percutaneous catheter in a patient with unidentified epidural lipomatosis.52 The catheter was readily placed under direct vision after laminotomy. We use a dual laminotomy technique in those cases in which a proper anatomic position cannot be achieved through a single laminotomy to enable proper anatomic and physiologic positioning of a flat electrode and have estimated that unanticipated anatomic complications occur as often as 18% of the time in revision flat electrode placements.51 Finally, it is uncommon, but it is sometimes impossible to obtain satisfactory paresthesia overlap of the painful area, particularly with angina pectoris and axial low back or neck pain, despite an unimpeded ability to manipulate the electrode(s). Even distal extremity paresthesia coverage can sometimes be impossible to obtain for unproven but theorized reasons such as epidural scarring or any impediment to the flow of electricity to and into the spinal cord.

Complications and Troubleshooting

Possible problems and complications of spinal cord stimulating devices have been well described. North and colleagues11 had no major morbidity or mortality in their series of 320 patients undergoing implantation over 20 years. Their incidence of surgical wound infections, all superficial, was 5%, and they all cleared promptly with the removal of hardware and a short course of antibiotics, permitting a second implantation. They had a 7% failure rate manifested by fracture of the electrode or insulation failure; 5% of their systems failed because of a defect in the radiofrequency receiver.

Patients should have a near-normal prothrombin time before proceeding with implantation. Patients with thrombocytopenia should be transfused with platelets before implantation. These patients should be carefully monitored for symptoms of acute epidural hematoma, and if these symptoms occur, they should be treated as a neurosurgical emergency.

Summary

SCS is the most useful new tool in the armamentarium combating chronic pain to emerge in more than a decade. Its use is supported not only by overwhelming case series but by well-controlled clinical trials. The precise niche for SCS in the management of angina pectoris, PVOD, and even chronic low back and neck pain is still developing in the paradigm of care for patients with chronic pain. Future vectors of care and usefulness include discovering the role of different drugs when used in combination with SCS. Subeffective doses of gabapentin and pregabalin when combined with subeffective levels of SCS have been shown to be effective in reducing neuropathic pain.53 Patients with neuropathic pain effectively treated with SCS have been shown in a double-blind, randomized study to respond to carbamazepine but not to sustained-release morphine when their SCS devices were turned off and they were “switched” to a painful state.54

Other areas under investigation include an automated, patient-interactive SCS adjustment device, which has been shown to provide better paresthesia overlap of painful regions, better analgesia, and longer battery life.55 Better methods of obtaining axial paresthesia coverage, electrode placement under the arch of C1 and C2 for use in atypical facial pain, nerve root SCS cannulation, chemical augmentation with intrathecally administered drugs, sacral root stimulation for urinary incontinence, and improvements in systems and equipment all may add to the success of SCS as a therapeutic, nondestructive, reversible, and minimally invasive analgesic tool.56

Intraspinal Infusion Systems

Introduction and General Selection Criteria

Intraspinal administration of opioids has been shown to be useful in patients who have not responded to other therapies or who have excessive side effects with other routes of administration. It is most useful and has proven efficacy when used for patients with cancer pain who develop unmanageable side effects to the high doses of opioids sometimes necessary to control pain or intractable pain states.57–63 Success in treating nonmalignant chronic pain with intraspinal opioids has not been confirmed to the same extent but is commonly employed.64,65 As with SCS, patient selection is likely to be the key predictor of success, but identifiable preimplantation variables have not yet been definitively identified. Negative predictors of success have been suggested to include major psychopathology, active mood disorders, dementia, severe anxiety, addictive disease, and severe social or economic stressors.

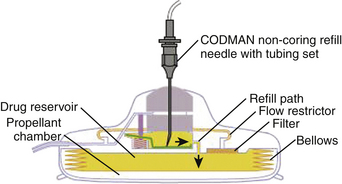

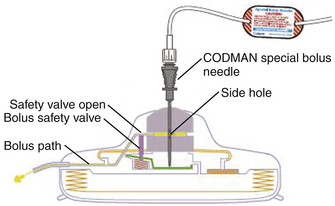

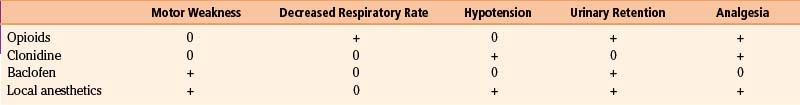

Patients whose pain does not respond to opioids may benefit from the addition of other drugs to their intraspinal regimen. Drugs reportedly used include local anesthetics, clonidine, baclofen, and opioids.3,66 Local anesthetics, clonidine, and baclofen are typically used in combination with opioids and, except for clonidine, may not be useful as analgesics when administered alone. A recent review investigated clinical practices via an Internet-based survey and described drugs and combinations of drugs used by practitioners.67 Drugs and combinations are shown in Fig. 129-5.

Drug Selection and Systems

The use of neuraxial morphine through a continuous infusion pump as an effective treatment for pain of malignant origin has been well documented.57–63 Morphine, hydromorphone, bupivacaine, baclofen, clonidine, sufentanil, ketamine, ropivacaine, fentanyl, meperidine, tetracaine, and experimental agents are used in academic pain centers in the United States.3 The use of spinally administered drugs in the noncancer pain group is more complex. The indication for this therapy is very simply opioid-responsive pain in patients unable to tolerate alternate routes of administration or in whom alternate routes of administration are ineffective. The complexity arises when considering the impact of social, psychological, physical, financial, and emotional factors. Further complicating the issue is the impact of ongoing litigation, disability, and substance abuse, which are so prevalent in our society.

In a blinded, placebo-controlled study conducted in Australia, less than one third of patients using oral opioids for nonmalignant pain were found to have opioid-responsive pain on intrathecal testing.68 Furthermore, these patients were significantly more distressed by testing with a battery of psychometric tools including the Beck Depression Inventory, Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire, and other measures of catastrophe and disability. These data are consistent with a recent report showing that 40% of patients treated with opioids in two major academic pain centers exhibited aberrant behaviors that could be construed as drug seeking or had urine toxicology results inconsistent with reported use of drugs.69 These studies underscore the complexities and difficulties inherent in treating patients with noncancer chronic pain.

Other problems in attempting to define efficacy in this group include the fact that there are only case series reporting the efficacy of intraspinal opioids in patients with nonmalignant pain and not the same overwhelming evidence of efficacy as exists for SCS. There are no studies with a control group comparison. There are few accurate descriptions of the incidence of continued use of supplemental oral opioids in patients receiving neuraxial opioids. Patients have not been stratified into etiologies of pain. Measurement of outcomes is largely unsatisfactory in all published studies. An expert panel recently produced an evidence-based review of the literature on intrathecal drug delivery, and their conclusion was that further study is warranted.70

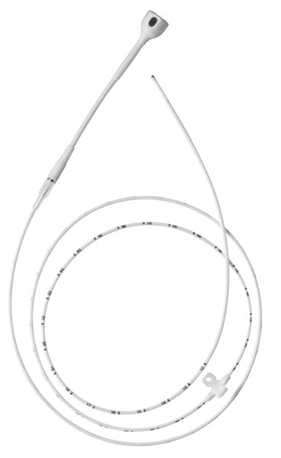

The literature addressing the efficacy of intraspinal opioids for the relief of pain has continued to expand since 1980 when Bromage and colleagues71 showed clearly that narcotics administered epidurally were capable of providing profound postoperative analgesia. Although postoperative and other short-term catheters for acute pain can be placed epidurally, catheters placed for cancer or long-term chronic pain conditions should be placed intrathecally. Catheter migration from the epidural to intrathecal space has been reported and can result in massive overdose and diffusion conditions across the dura/arachnoid membrane and can be affected by conditions such as carcinomatous meningitis or other inflammatory conditions, which can result in severe pain from a decrease in drug reaching the intrathecal space. For these reasons, catheters for implanted devices will typically be placed in the subarachnoid space.

The gold standard infusate for opioids administered via an implanted intraspinal device is morphine. Drug selection is a complex issue requiring knowledge and experience. Clinical guidelines for drug selection are shown in Fig. 129-6, and physiologic guidelines are outlined in Table 129-1.72 Morphine can be maximally concentrated to approximately 50 mg/ml and is commercially available at a concentration of 25 mg/ml. Hydromorphone is commonly used in spinally administered opioid infusion devices and is available in a concentration of 10 mg/ml. Clinicians can mix either morphine or hydromorphone (or another opioid) with bupivacaine in an attempt to manage severe neuropathic or somatic incident pain. Unfortunately, the maximal concentration of available bupivacaine is 40 mg/ml, limited by solubility, which may necessitate refilling the devices as often as monthly. The limiting factor is the size of the pump reservoir, which is only 18 ml in available programmable devices. Patients receiving bupivacaine infusion in their implanted devices often need to have refills on a monthly basis, whereas patients receiving opioid alone will usually require refills only every 90 days. Stability data for morphine in implanted pumps ensure stability for only 90 days.

FIGURE 129-6 Clinical guidelines for drug selection for intraspinal infusion.

(From Hassenbusch SJ, Portenoy RK, Cousins M, et al. Polyanalgesic consensus conference 2003: an update on the management of pain by intraspinal drug delivery—report of an expert panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;27:546-563.)

Trial, Implantation, and Complications

Before permanent implantation, it is generally accepted that a trial for responsiveness and tolerability is mandatory. Trials can be done by continuous infusion or bolus injection, with patients as inpatients or outpatients, and with drug administered epidurally or intrathecally for as short a period of time as 1 day, a single intrathecal bolus, or as long as 60 days. A recent comparison of a single intrathecal bolus of morphine versus as long as 4 days of continuous epidural infusion of morphine showed no difference in outcome.73 Whatever the method or rationale for a trial, it is imperative that the trial be adequate to satisfy the physician’s assessment of potential efficacy and tolerability. An arbitrary reduction in pain that has been selected by most practitioners is a 50% reduction in pain. This degree of reduction is necessary to define a trial sufficient to demonstrate the efficacy of an opioid.

The procedure is well described by an experienced group of implanters attempting to reach a consensus on the best technique, with special attention to a low technical complication rate.74 Complications addressed included catheter dislodgment and migration, fracture, kink or occlusion, cut or puncture, disconnect, and leak.

Other complications related to drug infusion devices have been described by Krames.75 Surgical complications include bleeding, infection, pump pocket seroma, cerebrospinal fluid leak, cerebrospinal fluid hygroma, postdural puncture headache, and improper pocket placement. Catheter tip fibroma formation has been reported and is discussed further. Catheter tip epidermoid tumors can occur if epidermal cell are delivered into the subarachnoid space when accessing via the epidural needle. A small skin incision with a scalpel blade is necessary before inserting the epidural needle to prevent this complication.

For a more thorough and recent review of neuraxial medication delivery including a literature review, indications, comparison of techniques, comparison of different types of pumps, and a synopsis of troubleshooting, the reader is referred to Prager.76

Summary

Spinal cord stimulation and the use of intraspinal infusion systems for cancer and chronic pain are efficacious, cost effective, and integral tools in the armamentarium of anyone treating cancer or chronic pain. Patient selection, improvement in systems, increased safety, and the development of new drugs are targets for future work.

Amann W., Berg P., Gersbach P., et al. Spinal cord stimulation in the treatment of non-reconstructable stable critical leg ischemia: results of the European peripheral vascular disease outcome study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2003;26:280-286.

Barolat G., Schwartzman R., Woo R. Epidural spinal cord stimulation in the management of reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1989;53:29-39.

Bennett G., Burchiel K., Buchser, et al. Clinical guidelines for intraspinal infusion: report of an expert panel. J Pain Sympt Manage. 2000;20:S37-S43.

de Jongste M.J.L., Hautvast R.W.M., Hillege H., et al. Efficacy of spinal cord stimulation as an adjuvant therapy for intractable angina pectoris: a prospective randomized clinical study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:1592-1597.

de Jongste M.J.L., Nagelkerke D., Hooyschuur C.M. Stimulation characteristics, complications, and efficacy of spinal cord stimulation systems in patients with refractory angina. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1994;17:1751-1760.

Ekre O., Eliasson T., Norrsell H., et al. Long-term effects of spinal cord stimulation and coronary artery bypass grafting on quality of life and survival in the ESBY study. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:1938-1945.

Fanciullo G.F., Rose R.J., Lunt P.G., et al. The state of implantable pain therapies in the United States: a nationwide survey of academic teaching programs. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:1311-1316.

Follett K.A., Burchiel K., Deer T., et al. Prevention of intrathecal drug delivery catheter-related complications. Neuromodulation. 2003;6:32-41.

Hassenbusch S.J., Prem P.K., Magdinec M., et al. Constant infusion of morphine for intractable cancer pain using an implanted pump. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:405-409.

Jacobs M.J., Jorning P.J., Beckers R.C., et al. Foot salvage and improvement of microvascular blood flow as a result of epidural spinal cord electrical stimulation. J Back Surg. 1990;12:354-360.

Krames E.S., Gershow J., Glassberg A., et al. Continuous infusion of spinally administered narcotics for the relief of pain due to malignant disorders. Cancer. 1985;56:696-702.

Kumar K., Malik S., Demeria D. Treatment of chronic pain with spinal cord stimulation versus alternative therapies: cost-effectiveness analysis. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:106-116.

Kumar K., Nath R.K., Toth C. Spinal cord stimulation is effective in the management of reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:503-509.

Kumar K., Nath R., Wyant G.N. Treatment of chronic pain by epidural spinal cord stimulation: a ten year experience. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:402-407.

Lind G., Meyerson B.A., Winter J., Linderoth B. Implantation of laminotomy electrodes for spinal cord stimulation in spinal anesthesia with intraoperative dorsal column activation. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:1150-1154.

North R.B., Kidd D.H., Lee M.S., et al. A prospective, randomized study of spinal cord stimulation versus reoperation for failed back surgery syndrome: initial results. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1994;62:267-272.

North R.T., Kidd D.H., Olin J.C., Sieracki J.M. Spinal cord stimulation electrode design: prospective, randomized, controlled trial comparing percutaneous and laminectomy electrodes. Part I. Technical outcomes. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:381-384.

North R.B., Kidd D.H., Zahuhurak M., et al. Spinal cord stimulation for chronic intractable pain: experience over two decades. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:384-395.

North R.B., Wetzel F.T. Spinal cord stimulation for chronic pain of spinal origin: a valuable long term solution. Spine. 2002;27:2584-2591.

Oakley J.C., Prager J.P. Spinal cord stimulation: mechanism of action. Spine. 2002;27:2574-2583.

Portenoy R.K., Hassenbusch S.J. Current practices in intraspinal therapy—a survey of clinical trends and decision making. J Pain Sympt Manage. 2000;20:S4-S11.

Romano M., Brusa S., Grieco A., et al. Efficacy and safety of permanent cardiac DDD pacing with contemporaneous double spinal cord stimulation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1998;1:465-467.

Sindou M.P., Mertens P., Bendavid U., et al. Predictive value for somatosensory evoked potentials for long-lasting pain relief after spinal cord stimulation: practical use for patient selection. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:1374-1384.

Turner J.A., Loeser J.D., Bell K.G. Spinal cord stimulation for chronic low back pain: a systematic literature synthesis. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:1088-1095.

Winkelmuller M., Winkelmuller W. Long-term effects of continuous intrathecal opioid treatment in chronic pain of nonmalignant etiology. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:458-467.

1. Shealy C.N., Mortimer J.T., Reswick J. Electrical inhibition of pain by stimulation of the dorsal column: preliminary clinical reports. Anesth Analg. 1967;46:489-491.

2. Kemler M.A., Barandse G.A.N., van Kleef M., et al. Spinal cord stimulation in patients with chronic reflex sympathetic dystrophy. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:618-624.

3. Fanciullo G.F., Rose R.J., Lunt P.G., et al. The state of implantable pain therapies in the United States: a nationwide survey of academic teaching programs. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:1311-1316.

4. Kumar K., Malik S., Demeria D. Treatment of chronic pain with spinal cord stimulation versus alternative therapies: cost-effectiveness analysis. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:106-116.

5. Kemler M.A., Furnee C.A. Economic evaluation of spinal cord stimulation for chronic reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Neurology. 2002;59:1203-1209.

6. Merry A.F., Smith W.M., Anderson D.J., et al. Cost-effectiveness of spinal cord stimulation in patients with intractable angina. N Z Med J. 2001;114:179-181.

7. Andrell P., Ekre, Eliasson T., et al. Cost-effectiveness of spinal cord stimulation versus coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with severe angina pectoris—long-term results from the ESBY Study. Cardiology. 2003;99:20-24.

8. Oakley J.C., Prager J.P. Spinal cord stimulation: mechanism of action. Spine. 2002;27:2574-2583.

9. North R.B., Wetzel F.T. Spinal cord stimulation for chronic pain of spinal origin: a valuable long term solution. Spine. 2002;27:2584-2591.

10. Kumar K., Nath R., Wyant G.N. Treatment of chronic pain by epidural spinal cord stimulation: a ten year experience. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:402-407.

11. North R.B., Kidd D.H., Zahuhurak M., et al. Spinal cord stimulation for chronic intractable pain: experience over two decades. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:384-395.

12. Turner J.A., Loeser J.D., Bell K.G. Spinal cord stimulation for chronic low back pain: a systematic literature synthesis. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:1088-1095.

13. North R.B., Kidd David H., Lee M.S., et al. A prospective, randomized study of spinal cord stimulation versus reoperation for failed back surgery syndrome: initial results. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1994;62:267-272.

14. Kim S.H., Tasker R.R., Oh M.Y. Spinal cord stimulation for nonspecific limb pain versus neuropathic pain and spontaneous versus evoked pain. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:1056-1065.

15. Canavero S., Bonicalzi V. Spinal cord stimulation for central pain. Pain. 2003;103:225-228.

16. Kirvela O.A., Kotilainen E. Successful treatment of whiplash-type injury induced severe pain syndrome with epidural stimulation: a case report. Pain. 1999;80:441-443.

17. Laffey J.G., Murphy D., Regan J., O’Keefe D. Efficacy of spinal cord stimulation for neuropathic pain following idiopathic acute transverse myelitis: a case report. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1999;101:125-127.

18. Sindou M.P., Mertens P., Bendavid U., et al. Predictive value for somatosensory evoked potentials for long-lasting pain relief after spinal cord stimulation: practical use for patient selection. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:1374-1384.

19. Harke H., Gretenkort P., Ladleif H.U., et al. Spinal cord stimulation in postherpetic neuralgia and in acute herpes zoster pain. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:694-700.

20. Broseta J., Barbera J., De Vera J.A., et al. Spinal cord stimulation in peripheral arterial disease: a cooperative study. J Neurosurg. 1986;64:71-80.

21. Jacobs M.J., Jorning P.J., Beckers R.C., et al. Foot salvage and improvement of microvascular blood flow as a result of epidural spinal cord electrical stimulation. J Back Surg. 1990;12:354-360.

22. Amann W., Berg P., Gersbach P., et al. Spinal cord stimulation in the treatment of non-reconstructable stable critical leg ischemia: results of the European peripheral vascular disease outcome study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2003;26:280-286.

23. Petrakis E., Sciacca V. Prospective study of transcutaneous oxygen tension measurement in the testing period of spinal cord stimulation in diabetic patients with critical lower limb ischemia. Int Angiol. 2000;19:18-25.

24. Petrakis E., Sciacca V. Does autonomic neuropathy influence spinal cord stimulation therapy success in diabetic patients with critical lower limb ischemia? Surg Neurol. 2000;53:182-189.

25. Neuhauser B., Perkmann R., Klingler P.J., et al. Clinical and objective data on spinal cord stimulation for the treatment of severe Raynaud’s phenomenon. Am Surg. 2001;67:1096-1097.

26. Chierichetti F., Mambrini S., Bagliani, Odero A. Treatment of Buerger’s disease with electrical spinal cord stimulation. Angiology. 2002;53:341-347.

27. Kumar K., Nath R.K., Toth C. Spinal cord stimulation is effective in the management of reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:503-509.

28. Barolat G., Schwartzman R., Woo R. Epidural spinal cord stimulation in the management of reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1989;53:29-39.

29. Hord E.D., Cohen S.P., Cosgrove G.R., et al. The predictive value of sympathetic block for the success of spinal cord stimulation. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:626-633.

30. Murphy D.F., Giles K.E. Dorsal column stimulation for pain relief from intractable angina pectoris. Pain. 1987;28:365-368.

31. Mannheimer C., Augustinsson L.E., Carlsson C.A., et al. Epidural spinal electrical stimulation in severe angina pectoris. Br Heart J. 1988;59:56-61.

32. Gonzalez-Darder J.M., Canela P., Martinez V.G. High cervical spinal cord stimulation for unstable angina pectoris. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1991;56:20-27.

33. de Jongste M.J.L., Staal M.J. Preliminary results of a randomized study on the clinical efficacy of spinal cord stimulation for refractory severe angina pectoris. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1993;58:161-164.

34. de Jongste M.J.L., Haaksma J., Hautvast R.W.M., et al. Effects of spinal cord stimulation on myocardial ischaemia during daily life in patients with severe coronary artery disease. Br Heart J. 1994;71:413-418.

35. de Jongste M.J.L., Nagelkerke D., Hooyschuur C.M. Stimulation characteristics, complications, and efficacy of spinal cord stimulation systems in patients with refractory angina. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1994;17:1751-1760.

36. Anderson C., Hole P., Oxhoj H. Does pain relief with spinal cord stimulation for angina conceal myocardial infarction? Br Heart J. 1994;71:419-421.

37. Anderson C., Hole P., Oxhoj H. Spinal cord stimulation as a pain treatment for angina pectoris. Pain Clinic. 1995;8:333-339.

38. De Jongst M.J.L., Hautvast R.W.M., Hillege H., et al. Efficacy of spinal cord stimulation as an adjuvant therapy for intractable angina pectoris: a prospective randomized clinical study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:1592-1597.

39. Bagger J.P., Jensen B.S., Johannsen G. Long-term outcome of spinal electrical stimulation in patients with refractory chest pain. Clin Cardiol. 1998;21:286-288.

40. Sanderson J.E., Brooksby P., Waterhouse D., et al. Epidural spinal electrical stimulation for severe angina: a study of effects on symptoms, exercise tolerance and degree of ischemia. Eur Heart J. 1992;13:628-633.

41. Janfaza D.R., Michna E., Pisini J.V., Ross E.L. Bedside implantation of a trial spinal cord stimulator for intractable anginal pain. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:1242-1244.

42. Fanciullo G.J., Robb J.F., Rose R.J., Sanders J.H. Spinal cord stimulation for intractable angina pectoris. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:305-306.

43. Ekre O., Eliasson T., Norrsell H., et al. Long-term effects of spinal cord stimulation and coronary artery bypass grafting on quality of life and survival in the ESBY study. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:1938-1945.

44. Jessurun G.A.J., de Jongste M.J.L., Hautvast R.W.M., et al. Clinical follow-up after cessation of chronic electrical neuromodulation in patients with severe coronary artery disease: a prospective randomized controlled study on putative involvement of sympathetic activity. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1999;22:1432-1439.

45. Murray S., Carson K.G.S., Ewings P.D., et al. Spinal cord stimulation significantly decreases the need for acute hospital admission for chest pain in patients with refractory angina pectoris. Heart. 1999;82:89-92.

46. Romano M., Brusa S., Grieco A., et al. Efficacy and safety of permanent cardiac DDD pacing with contemporaneous double spinal cord stimulation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1998;1:465-467.

47. Iyer R., Gnanadurai T.V., Forsey P. Management of cardiac pacemaker in a patient with spinal cord stimulator implant. Pain. 1998;74:333-335.

48. Lind G., Meyerson B.A., Winter J., Linderoth B. Implantation of laminotomy electrodes for spinal cord stimulation in spinal anesthesia with intraoperative dorsal column activation. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:1150-1154.

49. Villavicencio A.T., Leveque J.C., Rubin L., et al. Laminectomy versus percutaneous electrode placement for spinal cord stimulation. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:399-406.

50. North R.T., Kidd D.H., Olin J.C., Sieracki J.M. Spinal cord stimulation electrode design: prospective, randomized, controlled trial comparing percutaneous and laminectomy electrodes. Part I. Technical outcomes. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:381-384.

51. Ball P.A., Fanciullo G.J. Pont de dolor: a dual laminotomy technique for placing and securing an electrode in the epidural space and comments about anatomic variation that may complicate spinal cord stimulation electrode placement. Neuromodulation. 2003;6:92-94.

52. Huraibi H.A., Phillips J., Rose, et al. Intrathecal baclofen pump implantation complicated by epidural lipomatosis. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:429-431.

53. Wallin J., Cui J., Yakhnitsa V., et al. Gabapentin and pregablin suppress tactile allodynia and potentiate spinal cord stimulation in a model of neuropathy. Eur J Pain. 2002;6:261-272.

54. Harke H., Gretenkort P., Ladleif H., et al. The response of neuropathic pain and pain in complex regional pain syndrome I to carbamazepine and sustained-release morphine in patients pretreated with spinal cord stimulation: a double-blinded randomized study. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:488-495.

55. North R.B., Calkins S., Campbell D.S., et al. Automated, patient-interactive, spinal cord stimulator adjustment: a randomized controlled trial. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:572-580.

56. Barolat G., Sharon A.D. Future trends in spinal cords stimulation. Neurol Res. 2000;22:279-284.

57. Krames E.S., Gershow J., Glassberg A., et al. Continuous infusion of spinally administered narcotics for the relief of pain due to malignant disorders. Cancer. 1985;56:696-702.

58. Shetter A.G., Hadley M.N., Wilkinson E. Administration of intraspinal morphine sulphate for the treatment of intractable cancer pain. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:740-747.

59. Van Dongen R.T.W., Crul B.J.P., De Bock M. Long-term intrathecal infusion of morphine and morphine/bupivacaine mixtures in the treatment of cancer pain: a retrospective analysis of 51 cases. Pain. 1993;55:119-123.

60. Coombs D.W., Saunders R.L., Gaylor M., et al. Epidural narcotic infusion and reservoir: implantation technique and efficacy. Anesthesiology. 1982;56:469-473.

61. Andersen P.E., Cohen J.I., Everts E.C., et al. Intrathecal narcotics for relief of pain from head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117:1277-1280.

62. Hassenbusch S.J., Prem P.K., Magdinec M., et al. Constant infusion of morphine for intractable cancer pain using an implanted pump. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:405-409.

63. Krames E.S., Gershow J., Glassberg A., et al. Continuous infusion of spinally administered narcotics for the relief of pain due to malignant disorders. Cancer. 1985;56:696-702.

64. Magora F., Olshwang D., Eimerl D., et al. Observations on extradural morphine analgesia in various pain conditions. Br J Anaesth. 1980;52:247-252.

65. Winkelmuller M., Winkelmuller W. Long-term effects of continuous intrathecal opioid treatment in chronic pain of nonmalignant etiology. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:458-467.

66. Coombs D.W., Saunders M.D., Lechance B.S., et al. Intrathecal morphine tolerance: use of intrathecal clonidine, DADLE, and intraventricular morphine. Anesthesiology. 1985;62:358-363.

67. Portenoy R.K., Hassenbusch S.J. Current practices in intraspinal therapy—a survey of clinical trends and decision making. J Pain Sympt Manage. 2000;20:S4-S11.

68. Malloy A., Muir A., Sharp T., et al. Intrathecal testing with morphine in patients requiring regular opioids for analgesia. Negative responders were significantly more distressed and disabled than positive responders. In: Abstracts, 8th World Congress on Pain. Seattle: IASP Press; 1996:391-392.

69. Katz N.K., Sherburne S., Beach M., et al. Behavioral monitoring and urine toxicology testing in patients receiving long-term opioid therapy. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1097-1102.

70. Bennett G., Serafini M., Burchiel K.J., et al. Evidence-based review of the literature on intrathecal delivery of pain medicine. J Pain Sympt Manage. 2000;20:S12-S36.

71. Bromage P.R., Camporesi E., Chestnut D. Epidural narcotics for postoperative analgesia. Anesth Analg. 1980;59:473-480.

72. Bennett G., Burchiel K., Buchser, et al. Clinical guidelines for intraspinal infusion: report of an expert panel. J Pain Sympt Manage. 2000;20:S37-S43.

73. Anderson V.C., Burchiel K.J., Cooke B. A prospective randomized trial of intrathecal injection vs. epidural infusion in the selection of patients for continuous intrathecal opioid therapy. Neuromodulation. 2003;6:142-152.

74. Follett K.A., Burchiel K., Deer T., et al. Prevention of intrathecal drug delivery catheter-related complications. Neuromodulation. 2003;6:32-41.

75. Krames E.S. Intrathecal Infusional Therapies for Intractable Pain: patient management guidelines. Minneapolis: Medtronic Neurological; 1991.

76. Prager J.P. Neuraxial medication delivery: the development and maturity of a concept for treating chronic pain of spinal origin. Spine. 2002;27:2593-2605.