Chapter 598 Spinal Cord Disorders

598.1 Tethered Cord

In its simplest form the tethered cord syndrome results from a thickened filum terminale, which normally extends as a thin, very mobile structure from the tip of the conus to the sacrococcygeal region where it attaches. When this structure is thickened and shortened, the conus is found to end at levels below L2. This stretching between 2 points is likely to cause symptoms later in life. Fatty infiltration is often seen in the thickened filum (Fig. 598-1).

Figure 598-1 Sagittal MRI showing thickening of the filum terminale in a patient with a symptomatic tethered spinal cord.

(Used with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute.)

Any condition that fixes the spinal cord can be the cause of the tethered cord syndrome. Conditions that are well established to cause symptomatic tethering include various forms of occult dysraphism such as lipomyelomeningocele, myelocystocele, and diastematomyelia. These conditions are associated with cutaneous manifestations such as midline lipomas often with asymmetry of the gluteal fold (Fig. 598-2), and hairy patches called hypertrichosis (Fig. 598-3). Probably the most common type of symptomatic tethered cord involves patients who had previously undergone closure of an open myelomeningocele and later become symptomatic with pain or neurologic deterioration. Tethered cord syndrome can also be associated with attachment of the spinal cord in patients who undergo surgical procedures that disrupt the pial surface of the spinal cord.

Figure 598-3 Hairy patch or hypertrichosis usually associated with diastematomyelia.

(Used with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute.)

Clinical Manifestations

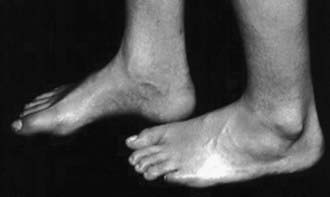

Patients at risk for the subsequent development of the tethered cord syndrome can often be identified at birth by the presence of an open myelomeningocele or by cutaneous manifestations of dysraphism. It is important to examine the back of the newborn for cutaneous midline lesions (lipoma, dermal sinus, tail, hair patch, hemangioma, port-wine stain) that may signal an underlying form of occult dysraphism. Dermal sinuses are usually located above the gluteal fold. Cutaneous abnormalities are not found in patients with an isolated thickened filum terminale. Patients who become symptomatic later in life often exhibit an asymmetry of the feet (i.e., one is smaller than the other). The smaller foot will show a high arch and clawing of the toes (Fig. 598-4). Characteristically, there is no ankle jerk on the involved side and the calf is atrophied. This condition is termed the neuro-orthopedic syndrome.

598.2 Diastematomyelia

Diastematomyelia: Split Cord Malformation

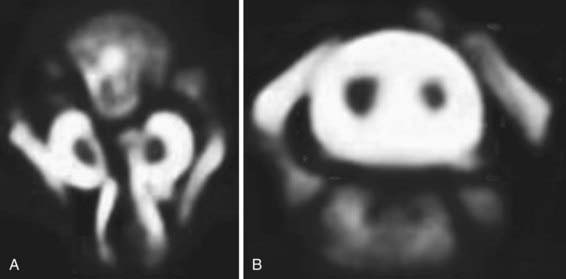

Diastematomyelia is a relatively rare form of occult dysraphism in which the spinal cord is divided into 2 halves. In type 1 split cord malformation, there are 2 spinal cords, each in its own dural tube and separated by a spicule of bone and cartilage (Fig. 598-5A). In a type 2 split cord malformation, the 2 spinal cords are enclosed in a single dural sac with a fibrous septum between the 2 spinal segments (Fig. 598-5B). In both cases the anatomy of the outer half of the spinal cord is essentially normal while the medial half is extremely underdeveloped. Undeveloped nerve roots and dentate ligaments terminate medially into the medial dural tube in type 1 cases and terminate in the membranous septum in type 2 cases. Both types have an associated defect in the bony spinal segment. In the case of type 2 lesions, this defect can be quite subtle.

598.3 Syringomyelia

Diagnostic Evaluation

MRI is the radiologic study of choice (Figs. 598-6 and 598-7). The study should include the entire spine and should include gadolinium-enhanced sequences. Specific attention should be paid to the craniovertebral junction due to the frequent association of syringomyelia with Chiari I and II malformations. Obstruction to the flow of CSF from the 4th ventricle can cause syringomyelia; therefore, most patients also should undergo imaging of the brain.

598.4 Spinal Cord Tumors

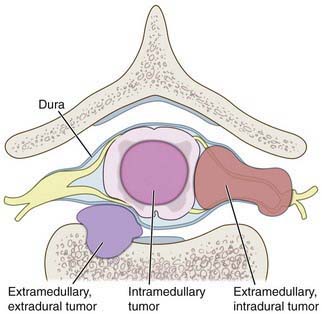

Tumors of the spine and spinal cord are rare in children. Different types of tumors have different relationships with the spinal cord, meninges, and bony elements of the spine (Fig. 598-8). Intramedullary spinal cord tumors arise within the substance of the spinal cord itself (Fig. 598-9). They represent between 5% and 15% of primary central nervous system tumors. This percentage may well reflect the total volume of spinal cord as opposed to brain. About 10% of intramedullary spinal cord tumors are malignant astrocytic tumors, but most are World Health Organization grade I or II tumors of glial or ependymal origin. In children, low-grade astrocytomas and gangliogliomas represent the most common tumor types with ependymomas being less common than in adults. Ependymomas in children are frequently associated with neurofibromatosis (NF 2).

Figure 598-8 Diagram of the relationship of various tumors to the spine, nerve roots, and spinal cord.

(Used with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute.)

McGirt MJ, Chaichana KL, Atiba A, et al. Resection of intramedullary spinal cord tumors in children: assessment of long-term motor and sensory deficits. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1:63-67.

Wilne S, Walker D. Spine and spinal cord tumours in children: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge to healthcare. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2010;95:47-54.

598.5 Spinal Cord Injuries in Children

Garton HJ, Hammer MR. Detection of pediatric cervical spine injury. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:700-708.

Lavy C, James A, Wilson-MacDonald J, et al. Cauda equina syndrome. BMJ. 2009;338:881-884.

Polk-Williams A, Carr BG, Blinman TA, et al. Cervical spine injury in young children: a National Trauma Data Bank review. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:1718-1721.

598.6 Transverse Myelitis

Transverse myelitis is a condition characterized by rapid development of both motor and sensory deficits (Table 598-1). It has multiple causes and tends to occur in 2 distinct contexts. Small children, 3 yr of age and younger, develop spinal cord dysfunction over hours to a few days. They have a history of an infectious disease, usually of viral origin, or of an immunization within the few weeks preceding the 1st development of their neurologic difficulties. The clinical loss of function is often severe and may seem complete. Although a slow recovery is common in these cases, it is likely to be incomplete. The likelihood of independent ambulation in these small children is about 40%. The pathologic findings of perivascular infiltration with mononuclear cells imply an infectious or inflammatory basis. Overt necrosis of spinal cord can be seen.

Table 598-1 DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR TRANSVERSE MYELITIS*

* Clinical events that are consistent with transverse myelitis but that are not associated with cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities or abnormalities detected on MRI and that have no identifiable underlying cause are categorized as possible idiopathic transverse myelitis.

† The IgG index is a measure of intrathecal synthesis of immunoglobulin and is calculated with the use of the following formula: (CSF IgG ÷ serum IgG) ÷ (CSF albumin ÷ serum albumin), where CSF denotes cerebrospinal fluid.

From Frohman EM, Wingerchuk DM: Transverse myelitis, N Engl J Med 363:564–572, 2010, Table 1, p 565.

Brinar VV, Habek M, Brinar M, et al. The differential diagnosis of acute transverse myelitis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2006;108:278-282.

Frohman EM, Wingerchuk DM. Transverse myelitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:564-572.

Krishnan C, Kaplin AI, Deshpande DM, et al. Transverse myelitis: pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Front Biosci. 2004;9:1483-1499.

Pawate S, Sriram S. Isolated longitudinal myelitis: a report of six cases. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:257-261.

Pidcock FS, Krishnan C, Crawford TO, et al. Acute transverse myelitis in childhood. Neurology. 2007;68:1474-1480.