Chapter 18 Special Topics

Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy

Reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD), now commonly referred to as complex regional pain syndrome 1 (CRPS), is a common disorder of unknown cause that often follows a relatively minor injury. It has been called by several names: Sudeck’s atrophy, causalgia, shoulder–hand syndrome, posttraumatic dystrophy, and others. The pathogenesis of the disorder is unclear, but a disturbance in the sympathetic nervous system apparently develops that leads to the characteristic symptoms and signs of intense pain (allodynia) and vasomotor disturbances. The condition usually affects the extremity rather than the torso. Early recognition is difficult. CRPS is divided into two types with similar clinical features, but type 2 is associated with more significant nerve injury, including causalgia and traumatic neuralgias.

CLINICAL FEATURES

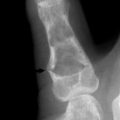

Although no imaging studies are diagnostic, plain roentgenograms may eventually reveal patchy osteoporosis (Fig. 18-1). The bone scan may be positive, showing regional uptake that is diagnostic and reflects increased blood flow.

Rotational Deformities of the Legs in Children

Developmental abnormalities of the lower extremities are common and are frequently a source of concern to parents. The cause of these deformities is unknown, but hereditary and persistent postnatal malpositioning play important roles. Most correct themselves spontaneously.

IN-TOEING

All three of these deformities are aggravated by positions or postures that are frequently assumed by the child or infant. Lying in the prone position with the legs extended and the feet internally rotated is often associated with in-toeing deformity. Sitting in the “reverse-tailor” position with the feet internally rotated beneath the buttocks is directly related to persistent tibial rotation and adduction of the forefoot (Fig. 18-2). Children may assume these positions for extended periods of time while sleeping, playing, or watching television.

INTERNAL FEMORAL TORSION

The diagnosis is made by clinical examination. It is helpful to mark the patellae and observe their position as the child walks. If the child toes in and the patellae face medially, excessive femoral anteversion or an internal rotation contracture of the hips should be suspected. If the child toes in and the patellae face straight forward, then the deformity has to be distal to the knee, either internal tibial torsion or metatarsus varus. Internal femoral torsion can also be measured with the patient prone, the hips extended, and the knees flexed 90 degrees (Fig. 18-3). External and internal measurements of hip motion are then made, with the tibia acting as a pointer. An internal rotation deformity exists at the hip when internal rotation exceeds external rotation by more than 30 degrees.

INTERNAL TIBIAL TORSION

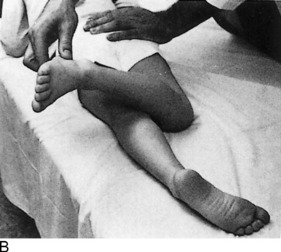

An approximate measurement of tibial torsion can be obtained by having the patient sit on the examining table with the knees flexed 90 degrees over the side. The tibial tubercle is palpated and directed straight forward. The malleoli are then grasped with the thumb and index finger, and the position of the axis of the ankle joint is determined (Fig. 18-4). Normally, 20 to 30 degrees of external tibial torsion is present in adults, and the lateral malleolus is slightly posterior to the medial malleolus. In children with internal tibial torsion, the lateral malleolus is anterior to the medial malleolus.

METATARSUS VARUS

With the child in the same sitting position, the foot is examined for deformity. If metatarsus varus is present, the lateral border of the foot is convex, and the medial border is concave (Fig. 18-5).

TREATMENT

Tibial torsion is best treated by observation and reassurance. Spontaneous correction usually occurs with growth. Improper sitting and sleeping habits should be corrected. Stretching exercises are of no value. Corrective shoes appear to be of no benefit in the treatment of any of these problems.

The treatment of metatarsus varus depends on whether the deformity is fixed. If the foot is flexible and the deformity easily overcorrectable, passive stretching exercises and a straight or reverse-last shoe are sometimes tried, although their effectiveness is unknown (Fig. 18-6). If the forefoot is rigid and passive correction of the deformity is not possible, early treatment with corrective casts may be indicated. The correction should begin shortly after birth. When the disorder is seen after the age of 1 or 2 years, operative intervention is occasionally necessary. Early diagnosis is therefore important.

OUT-TOEING

External rotation deformity of the lower extremities is usually caused by the following: (1) external rotation of the hip secondary to soft tissue contracture or femoral retroversion (external femoral torsion), (2) external tibial torsion, or (3) pes calcaneovalgus, or flatfeet. Out-toeing is often associated with a genu valgum deformity and may be aggravated by sleeping in the prone position (Fig. 18-7). The use of wide diapers or a children’s “walker” with a wide pad may potentiate an externally rotated gait.

If femoral retroversion is the cause, examination reveals that external rotation of the hips is significantly greater than internal rotation. External tibial torsion is diagnosed by the marked posterior position of the lateral malleolus compared with the medial. The flatfoot deformity is frequently associated with eversion of the heels (see Chapter 12).

Angular Deformities of the Legs in Children

GENU VARUM (BOWED LEGS)

The child is commonly brought to the doctor because of the wide space between the knees and the mild in-toeing gait. Other possible causes of bowing (such as rickets and Blount’s disease) can generally be ruled out by the child’s history. Roentgenograms may be necessary. There is usually no evidence of any intrinsic bone disease. The amount of genu varum can be determined by measuring the distance between the medial femoral condyles with the child standing and the medial malleoli touching.

BLOUNT’S DISEASE

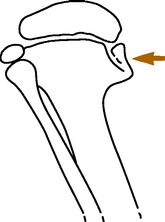

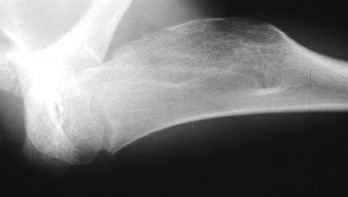

This is an uncommon pathologic, developmental bowing that results from altered growth of the upper medial tibial epiphysis (Fig. 18-8). The cause is unknown, but abnormal pressure may play a role. Blount’s disease is more common in obese early walkers and children of short stature. It is also more common in blacks. It may be unilateral, in contrast to physiologic bowing, which is almost always bilateral. Two forms of Blount’s disease are described: an infantile type, which begins before age 3; and an adolescent form, which starts after age 8. Before the age of 2, the infantile form may be difficult to differentiate from physiologic bowing, especially if it is bilateral. Although physiologic bowing resolves with growth, Blount’s disease progressively worsens. A strong family history and severe bowing are indications for roentgenographic evaluation.

GENU VALGUM (KNOCK-KNEE)

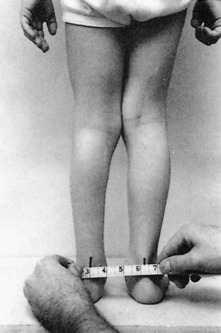

Knock-knee may be caused by a variety of disorders, including injury and metabolic disease. However, most genu valgum is present as one stage in the normal physiologic “swing” between developmental genu varum and normal alignment. It is usually bilateral and is most common between the ages of 2 and 4 years. The severity of the deformity can be determined by measuring between the medial malleoli or Achilles tendons with the child standing, the medial femoral condyles touching, and the patellae facing forward (Fig. 18-9). Similar measurements can be taken on return visits to confirm spontaneous correction if reassurance is needed.

Leg Length Inequality

Limb length discrepancies in the lower extremities may result from several causes. The most common are fractures, osteomyelitis, neuromuscular disease, and vascular anomalies. Usually, the affected limb is shorter, but occasionally the inequality is the result of overgrowth because of epiphyseal stimulation by inflammation or injury. Frequently, no cause is found. The inequality may cause a mild limp and compensatory scoliosis.

Primary Bone Tumors

BENIGN BONE TUMORS

Most common benign bony neoplasms are either fibrous or cartilaginous. Cystic lesions such the simple bone cyst (see Chapter 5) occur with some frequency but may not be true neoplasms. The benign lesions that occur with any frequency are as follows: (1) fibrous cortical defect; (2), nonossifying fibroma; (3) fibrous dysplasia; (4) enchondroma; and (5) osteochondroma. Most of these lesions are diagnosed by a specific clinical and radiographic presentation, often related to the age of the patient and the bone involved. And although the radiographic appearance may not always be pathognomonic in all cases, certain characteristics are highly suggestive of specific lesions. Radiologic or orthopedic referral is valuable to determine the significance of such lesions.

Enchondromas are benign tumors of cartilage usually located centrally in bone. The most common sites are the small bones of the hand and feet (Fig. 18-10). The enchondroma is the most common tumor of the bones of the hand. It most often occurs in patients between the ages of 10 and 50 years. Symptoms are nonspecific. The lesion is usually discovered incidentally or is identified after a pathologic fracture. Treatment is simple observation if the diagnosis is obvious. If enough bone weakness is present, leading to recurrent fracture, or if the diagnosis is uncertain, surgical intervention is indicated.

FIG. 18-10 Enchondroma of the phalanx. The lesion is well circumscribed. A pathologic fracture is present.

Osteochondromas are the most common of all benign bone growths. They may not actually be neoplasms but are more likely developmental abnormalities thought to be the result of some “pinching-off” of a portion of growth cartilage. This lesion begins to grow separately, and its growth ceases when the patient reaches skeletal maturity. The typical site of formation is on the metaphysis near the growth plate of the distal femur or proximal tibia, but they can be found on other long bones (Fig. 18-11). Most lesions consist of a stalk that is directed away from the growth plate from which it originated. The lesion is covered with a cartilaginous cap. Signs and symptoms are related to the presence of the mass, but most are only minimally symptomatic. The lesion is removed if producing symptoms. These lesions commonly regress when growth ceases.

Fibrous lesions of bone are common benign neoplasms that are usually discovered incidentally. Fibrous cortical defects are common in growing bone and have a characteristic radiographic appearance (Fig. 18-12). They are asymptomatic and do not require further investigation or treatment. The lesions most likely resolve within 2 to 3 years.

Nonossifying fibromas are similar lesions histologically but are much larger (Fig. 18-13). Biopsy is not usually required, but treatment may be needed in large lesions that are painful. These often regress as well.

Fibrous dysplasia is a developmental disturbance of bone formation in which fibroplastic proliferation occurs. The disorder may be monostotic or polyostotic. Endocrine abnormalities may also be present. Marked deformities may develop over time. The tibia is commonly involved, and pathologic fracture may occur (Fig. 18-14). Referral for surgery is indicated when deformity or pathologic fracture develops.

MALIGNANT BONE TUMORS

Primary malignant bone tumors are invasive, anaplastic, and have the ability to metastasize. Most arise from the marrow (myeloma), but tumors may develop from bone, cartilage, fat, and fibrous tissues. Leukemia and lymphoma are excluded from this discussion. Fibrosarcoma and liposarcoma are extremely rare. They are similar to those tumors arising in soft tissue. Osteosarcoma is an uncommon primary malignant tumor of bone characterized by malignant tumor cells that produce osteoid or bone. Several variants have been described: parosteal sarcoma, periosteal sarcoma, multicentric, and telangiectatic forms. Chondrosarcoma is a malignant cartilage tumor that may develop primarily or secondarily from transformation of a benign osteocartilaginous exostosis or enchondroma. Ewing’s sarcoma is a malignant tumor of unknown histogenesis, and multiple myeloma is a neoplastic proliferation of plasma cells.

EVALUATION

Speckled calcifications in a destructive radiolucent lesion are usually suggestive of chondrosarcoma. Ewing’s sarcoma is characterized radiographically by mottled, irregular destructive changes with periosteal new bone formation. The latter may be multilayered, producing the typical “onion skin” appearance.

The typical roentgenographic finding in multiple myeloma is the “punched-out” lesion with sharply demarcated edges (Fig. 18-15). Other characteristics include the following: (1) multiple lesions are usual; (2) diffuse osteoporosis may be the only finding in many cases; and (3) pathologic fractures are common.

Spinal Cord Compression

CLINICAL FEATURES

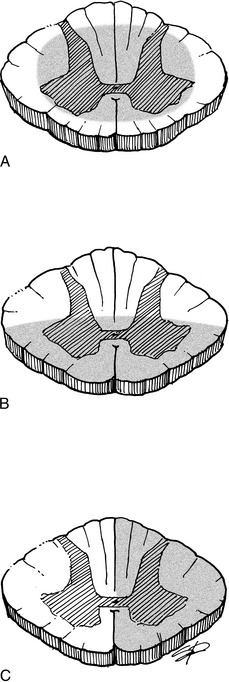

Clinical findings reflect the amount of spinal cord involvement (Fig. 18-16): there are usually motor loss and sensory abnormalities. Babinski testing is usually positive, and clonus is commonly present. Gradual compression is often manifested by progressive difficulty walking, clonus with weight bearing, and involuntary spasm; development of sensory symptoms; bladder dysfunction is a late finding. The following list describes findings in various types of spinal cord syndromes:

ETIOLOGY

Among the most common causes of spinal cord syndromes are trauma, tumor, infection, and degenerative disc conditions with spinal stenosis. Sometimes the central cord syndrome develops from compression of the cord from the front by a bulging or degenerative disc and from the back by a buckled ligamentum flavum. The stenotic spine may be more susceptible. Other causes of cord compression are inflammatory processes, cystic abnormalities, and severe disc herniation.

Spinal Braces

CERVICAL COLLARS

Cervical collars extend from the head to the thorax and are usually soft, although semirigid collars are also available (Fig. 18-17). The soft collar is usually more comfortable but restricts motion less than the other collars. These appliances are all used in the treatment of degenerative disc disease and minor ligamentous or muscular injuries of the cervical spine.

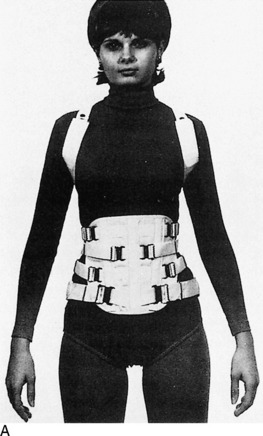

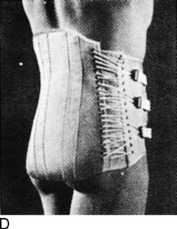

TAYLOR BRACE

This is a fundamental back brace useful in dorsal and lumbar spine disease (Fig 18-18). It is a high, semirigid brace that may be modified. Degenerative disc disease and minor fractures may be treated with this brace or one of its modifications (long Taylor, modified Taylor, and short Taylor).

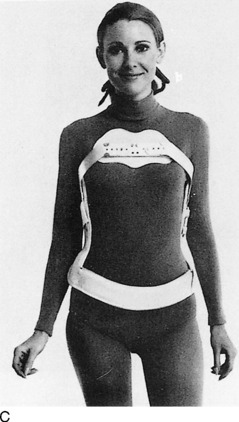

JEWETT (HYPEREXTENSION) BRACE

This three-point brace provides pressure over the lumbar spine, sternum, and symphysis pubis. It is used in minor fractures of the dorsal spine when extension is desired. It is also useful in the treatment of epiphysitis.

Disability Rating

Physical impairment can usually be measured accurately on the basis of the loss of physical function. A careful clinical history and physical examination are mandatory. Laboratory and roentgenographic analysis may also be necessary.

Joint Replacement Surgery

Great advances have been made in the past 25 years in the surgical treatment of degenerative and rheumatoid arthritis. These advances have been primarily caused by improvements in the techniques of joint arthroplasty. This procedure is most commonly used for conditions of the hip and knee, but devices have been developed for use in almost every joint (Fig. 18-19). The indications for surgery are the presence of arthritis and failed medical management.

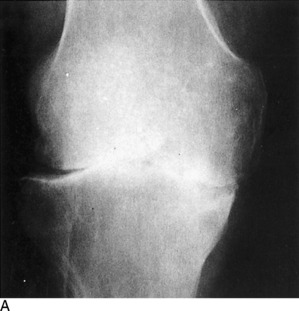

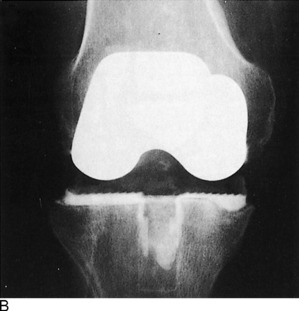

The basic purpose of these techniques is to implant a device into the joint that replaces the degenerated articular surfaces. Most joint replacement procedures use a hard plastic, high-density polyethylene for the socket (Fig. 18-20). This articulates with a metallic component, both components usually being fixed to the bone by a cementing compound, methylmethacrylate, or by an in-growth system.

FIG. 18-20 A, Degenerative arthritis of the knee. B, Postoperative roentgenogram after total knee replacement.

Mechanical problems with total knee replacement are slightly more common than those after total hip replacement, but the results are uniformly good in both procedures. More than 90% of patients undergoing arthroplasty have excellent relief of pain and improvement in motion. Short-term problems are those related to infection and venous thrombosis, both of which are treated prophylactically. Long-term concerns include aseptic loosening and osteolysis, a term used to describe an inflammatory response to particulate debris that can lead to bone loss and implant failure.

Compartment Syndromes of the Lower Leg

Compartment syndromes are disorders of the extremities in which increased tissue pressure compromises the circulation to the muscles and nerves within the space (see Chapter 15). These conditions are most common in the lower part of the leg, where four natural compartments exist (anterior, lateral, deep posterior, and superficial posterior). The anterior compartment is most commonly involved.

TREATMENT

Chronic cases usually subside with rest, but fasciotomy is occasionally performed to prevent recurrence. The acute form requires immediate surgical decompression. Without treatment, necrosis of muscle and nerve may occur and result in permanent weakness, contracture, and nerve dysfunction similar to Volkmann’s ischemic contracture in the upper extremity (see Chapter 2).

Injection and Aspiration Therapy

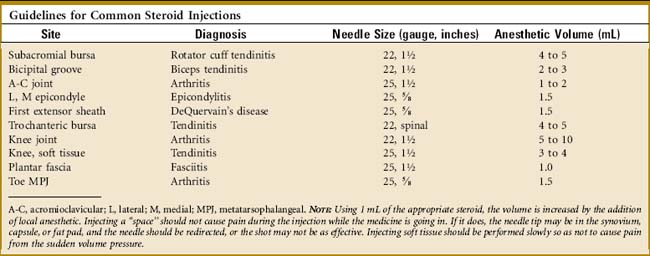

The ability of steroids to relieve pain and improve the function of inflamed joints, tendons, and bursae is unquestioned. And although a cellular inflammatory response is not always present in those disorders usually called “arthritis” and “tendinitis,” corticosteroid injections have been shown by randomized, controlled trials to provide excellent relief of pain in these conditions. The exact mechanism by which this is accomplished is unknown. It is theorized that these drugs reduce the local infiltration of those cells and compounds that mediate the inflammatory response. An increase in local blood flow and improvement in local tissue metabolism are other common explanations. A placebo effect is undoubtedly present in some cases. Systemic absorption is less after their use than it is with oral administration. However, some absorption does occur, and plasma cortisol levels can be suppressed for up to 1 week after injection. Markers of bone formation, such as osteocalcin, can also be depressed transiently but return to normal in 2 weeks after intraarticular use of a corticosteroid, while markers for bone resorption do not change, suggesting that there is no effect on bone resorption and only a temporary effect on bone formation.

The lidocaine and steroid may be injected separately but are usually mixed together. The use of a small amount of lidocaine alone for skin and soft tissue infiltration may be necessary in the apprehensive patient. If a joint with a thick capsule is to be entered, the capsule may also need to be infiltrated because passing a larger needle through the capsule may be uncomfortable for the patient. Do not use the steroid mixture to anesthetize the site; use only the anesthetic. Otherwise, atrophy may occur. The anesthetic is best injected with a 25-gauge needle (⅝-inch or 1 ½-inch). This needle size may also be used to inject the steroid–lidocaine mixture, especially if the injection is superficial. A 22-gauge, 1 ½-inch needle is sometimes necessary in deeper injections. A “giving” sensation usually occurs as the needle penetrates the tough, fibrous capsule, especially in the knee. The needle should not be advanced once the joint has been entered to avoid joint trauma. Aspirating the syringe while withdrawing the needle may prevent residual drops of the mixture from contaminating the skin and subcutaneous tissue.

The dose of cortisone is usually based on volume; 1 to 2 mL is used for larger joints and lesser amounts for smaller joints (Table 18-1). Tendons, except the quadriceps and elbow epicondyles, usually are not directly injected. Instead, it is usually a space (joint, tendon sheath or subacromial space) that is injected. There should be little resistance when injecting a space. If resistance occurs, the needle tip is probably incorrectly placed in some soft tissue, and its position should be changed. The volume of fluid injected depends on the size of the joint or soft tissue area.

NOTE: It has not been proven that there are any serious long-term systemic adverse effects to the occasional steroid injection, and the results of investigations into whether any local cartilage or soft tissue damage can occur are conflicted. Threshold doses among individuals regarding side effects seem to differ, but even short courses of treatment at high doses appears to have low risk. It has always been recommended that no more than three or four shots per year be given to the same joint. Although this limit seems sensible, it is not evidence based and is completely anecdotal. Some patients may require injections more often. If the patient’s symptoms are not well controlled with a reasonable frequency of injections, it may be necessary to reassess the disorder to be certain the diagnosis is correct and to even reevaluate other options.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

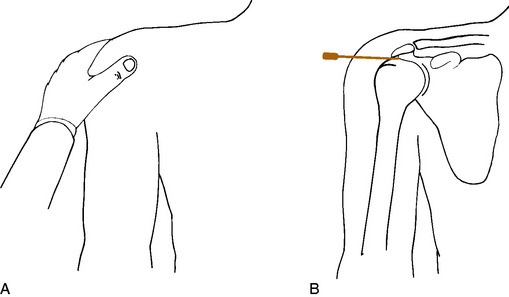

SOFT TISSUE INJECTION

Painful disorders of the soft tissue include such conditions as bursitis, tendinitis, tenosynovitis, trigger points, and so-called fibrositis. Most of these conditions have been previously described. Injection therapy is a mainstay of their treatment program (Fig. 18-21) Trigger points, fibrositis, and other similar syndromes are poorly understood disorders that present with pain and localized tenderness. A common site for the development of these tender areas is the spine, especially the interscapular and lumbosacral areas. Injecting these tender points is a common practice, but symptomatic relief is hard to analyze.

JOINT INJECTION

There are often occasions when intraarticular injection, sometimes accompanied by aspiration, is helpful in the treatment of painful joint disorders. This is more easily performed when an effusion is present. Except for the shoulder and hip, most joints are entered on their extensor aspect (Fig. 18-22). The major neurovascular bundle is usually found on the flexor side. Fluid usually distends the joint most in the direction of the extensor side, which makes entrance easier.

Frostbite

TREATMENT

Treatment of frostbite depends on the severity of involvement. Mild exposure is treated by removing all wet and constricting clothing in a sheltered area. The part is warmed by applying gentle pressure or, as in the case of the hands and feet, by placing the part under an armpit or on the abdomen beneath the clothing of another individual. The part should never be rubbed or massaged. Thawing should be avoided if there is any risk of refreezing. Nicotine and caffeine should be avoided.

Disorders of Treatment

ULNAR NEURITIS

This condition may develop in the hospitalized patient and usually results from sleeping in the supine position with the elbows slightly flexed and resting on the bed. It often results when the elbows are used to push up from the bed. Pain and numbness along the ulnar nerve distribution are typical symptoms, and the nerve is tender to palpation at the elbow. The condition is often bilateral. It sometimes develops from the patient lying in supine position during surgery. The disorder is prevented by having the patient wear soft pads strapped to the elbow to prevent pressure. The patient is not allowed to lie with the elbows in slight flexion, and a trapeze should always be available so that the patient will not have to use the elbows for propping up. Once the symptoms occur, surgical treatment is occasionally necessary.

Rickets

ETIOLOGY

True classic vitamin D–deficient rickets is rare in Western society. Absorption of vitamin D, however, may be blocked in several gastrointestinal disorders. Similar conditions may also prevent absorption of calcium and phosphorus, but in the absence of these diseases, deficiencies of calcium and phosphorus are also rare.

Paget’s Disease (Osteitis Deformans)

CLINICAL FEATURES

Characteristic bone hypertrophy leads to skull enlargement and bony overgrowth of the spine. This can produce neurologic complications (vision, hearing loss, radicular pain, and cord compression). Serum calcium and phosphate levels are normal, and the alkaline phosphatase level is elevated. Serum bone-specific alkaline phosphatase analysis may be most helpful. There is increased urinary excretion of pyridinoline, although this test is expensive and not usually needed in routine cases. Roentgenograms show dense expanded bones with characteristic radiolucency and opacity. (Fig. 18-23). Bone scanning reflects the extent and activity of the disease.

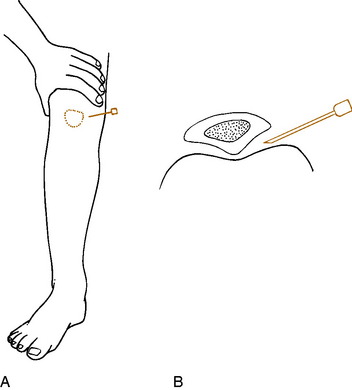

Miscellaneous Neuromuscular Disorders

PERIPHERAL NERVE COMPRESSION SYNDROMES

Localized injury and compression of peripheral nerves are common problems. The more frequent disorders have been previously discussed. Other syndromes are similarly caused by trauma or inflammation (Table 18-2). Early recognition is the key to effective treatment. Frequently, only the distal sensory portion of the nerve is involved. If superficial, Tinel’s sign is usually positive. Minor sensory deficits are commonly present.

POSTPOLIO SEQUELAE

MANAGEMENT

Reassurance and understanding are the most important tactics in treatment. Very few patients who have had polio have any serious progression of their weakness. The role of exercise has not been clearly established, but excessive physical strain should be avoided, and these patients probably benefit from a careful, nonfatiguing, resistive exercise program. Braces, orthotics, and other assistive devices should be evaluated and updated or modified as necessary.

CHARCOT–MARIE–TOOTH DISEASE

CLINICAL FEATURES

The onset is usually gradual, and the condition typically runs a slowly progressive course. The lower extremities are primarily involved. Peroneal muscle weakness may be an early finding. A high arch (cavus) and hammered toes are characteristic developments. Atrophy of the lower legs often produces a stork-like appearance. Muscle wasting does not involve the upper legs. Hypertrophic changes may develop in some peripheral nerves. Sensory loss, painful paresthesias, or other neurologic signs may occur although the sensory loss is usually mild. Deep tendon reflexes are absent in many cases, and decreased proprioception often interferes with balance and gait. Poorly healing foot ulcers develop in some cases. Late in the disorder, the hands may become involved.

SYRINGOMYELIA

This disease of the spine is characterized by the formation of fluid-filled cavities within the spinal cord, sometimes extending into the brain stem (see Chapter 16). The cause is unknown, but the condition is thought to be due to obstruction of the fourth ventricle, often associated with a Chiari I malformation, which causes fluid to be diverted down the central cord. Later in life, syrinxes may be caused by trauma or the result of an imtramedullary tumor.

MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS

SPECIAL STUDIES

MRI is the preferred imaging modality. Typical abnormalities (periventricular plaques) are found in the majority of cases and, when combined with a positive history and neurologic examination, usually establish the diagnosis without further testing. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) usually has elevated protein and leukocyte levels. The gammaglobulin level is often increased (in 70% of cases), and agar gel electrophoresis of concentrated CSF often shows migration in a typical pattern called oligoclonal bands.

Exercise and Good Health

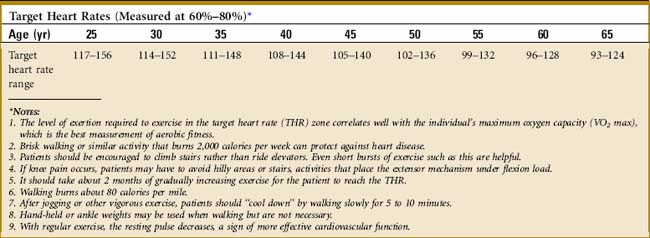

AEROBIC EXERCISE

The individual’s THR is determined by first subtracting the patients age from 220 to obtain that individual’s maximum heart rate (MHR). That figure is then multiplied by 0.60 to 0.80 to determine the target heart rate zone (Table 18-3). Exercise performed in this zone improves aerobic conditioning.

WALKING AND JOGGING

These are certainly the simplest of aerobic exercises. Because it is “low impact” (no excessive jumping or pounding), brisk walking is easier on the back and legs and provides about the same benefits as jogging. Walking is also the least risky exercise for those individuals with chronic medical problems. In addition to improving cardiovascular function, walking may also (1) help slow bone loss, especially in women; (2) extend life (walking 12–20 miles per week will decrease the annual death risk by about 27%); (3) help control cholesterol levels; and (4) help control weight. As with all exercise, the activity should be begun slowly. Eventually, the patient should walk at least four times per week for about 45 to 60 minutes while pausing from time to time to check the heart rate. Usually, walking at a rate of 120 steps per minute is adequate. For walking, warming up is not necessary, but a “cool-down period” after finishing running is better than stopping abruptly.

Once the patient is comfortable walking, jogging may be tried. A slow pace is more than adequate.

OTHER EXERCISES

Swimming, cycling, rowing, cross-country skiing, and jumping rope are also excellent aerobic activities. Swimming removes the body weight and may be better in patients with painful joints. Swimmers should avoid any stroke that requires that the neck be extended and the chin raised, because this can irritate cervical disc disease. Goggles and snorkel help prevent excessive neck motions and subsequent pain. Swimming at a THR for 20 to 30 minutes three times per week is sufficient. If cycling is tried, the bike needs to fit properly so that the lower portion of the back does not become strained. Stretching exercises may be good before any vigorous exercise. Stretching should be done after warming up for 5 minutes by walking (see Chapter 15). Cold muscles should not be stretched.

EXERCISE FOR THE ELDERLY

Flexibility exercises should start slowly. Those range-of-motion activities that occur with normal daily activities are not sufficient. Shoulder stretches (Chapter 5) are begun with the goals of being able to put the hand into the back pocket, comb the hair on the back of the head (both arms), and abduct the arm 90 degrees. Flexion of the hip is usually sufficient, but a mild flexion contracture may be present that may require extension exercises of the hip to improve gait and posture.

Balance may be able to be improved by activities sometimes called “movement therapies” or postural re-education. The most popular of these are toga, tai chi, and Pilates, especially those forms that emphasize slow smooth movement. Benefits from these nontraditional activities are hard to measure and are largely anecdotal but all of them are very popular. Meditation, relaxation, and breathing techniques are often part of the program. Most of these therapies are available with supervisors, but tapes and DVDs can also be purchased at a reasonable price.

Local Soft Tissue Treatment

TREATMENT OF CHRONIC DISORDERS

HEAT THERAPY

Deep heat is usually available as shortwave diathermy, microwaves, and ultrasound. Diathermy and ultrasound are more commonly used. The type must be specified.

The following points should be remembered when using any form of heat:

CANES, CRUTCHES, AND WALKERS

Use of the cane has long been advocated for pain relief in the treatment of arthritis of the lower extremity. Such arthritis often causes a painful and unsightly limp, which is usually fatiguing and may even cause low back pain. As advances have been made in orthopedic surgery and demands made by patients, both the patient and physician may too quickly opt for a high-technology joint replacement rather than succumb to the indignity of trying the most time-honored device for relieving pain and limp. Suggesting the use of a cane in an arthritic patient almost always requires some sensitive coaxing, and better education of the general public regarding the benefits of a cane would be helpful in this regard. It is usually the patient’s pride or the psychological aversion to using the cane that needs to be overcome. The positive aspects of cane use should be presented. Patients need to understand that they would probably look better using a cane that could eliminate their pain and limp than walking with the limp itself. An attractive cane formerly was a symbol of elegance and not a stigma of the aging process. If those attitudes could be encouraged, perhaps more patients could be treated nonsurgically.

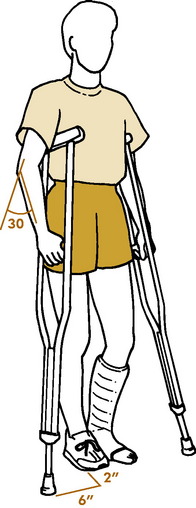

Crutches, walkers, and four-poster canes are used for stability, as well as pain relief and protection from weight bearing. They provide a broad base that increases the base of support and decreases the precision of coordination necessary during ambulation. Four-poster canes can only be used to push in the downward direction. Crutches need to be accurately adjusted (Fig. 18-24). Crutches that are too long may cause pressure on the axillary structures and result in crutch palsy. The hand piece of the crutch or walker should be at the same height as the cane so that it lies at wrist level with the elbow flexed 30 degrees.

Controversies in Orthopedic Surgery

LUMBAR FUSION FOR DISC DEGENERATION

Fusion (arthrodesis) for arthritic conditions involving peripheral joints has been and remains an excellent procedure for the relief of pain and correction of deformity. It has been supplanted by total arthroplasty in some joints, but it remains the procedure of choice in others. Because of the great success with peripheral joint fusion, attempts have been made over the years to transfer that knowledge and technique to degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine in an attempt to cure low back pain. In years past, fusion was actually used by some surgeons each time a lumbar discectomy was performed. Because of the high failure rate in curing low back pain, arthrodesis of the spine for disc degeneration lost popularity, but recent technical advances in roentgenographic imaging techniques and internal fixation devices have rekindled interest in the procedure. However, some recent studies have questioned the appropriateness of these procedures and their cost. Lumbar fusion is clearly indicated for trauma, scoliosis, and spondylolisthesis, but considerable uncertainty remains regarding its efficacy for the relief of the common low back pain due to disc degeneration.

ARTHROSCOPY

The second area of controversial arthroscopic use involves the disorder called anterior knee pain (Chapter 11). This “syndrome” typically occurs in many adolescents and may continue for years. Some of these patients may be found to have chondromalacia arthroscopically. They sometimes respond poorly to physical therapy, and there is a great tendency to try to find some surgical cure by shaving the articular cartilage in the back of the patella. Anterior knee pain and the pathologic changes of chondromalacia are probably unrelated, and even though conservative management has a high failure rate, arthroscopic investigation of the knee in such cases with or without debridement of cartilage lesions does not seem to be beneficial. Conservative care usually remains the treatment of choice.

THORACIC OUTLET SYNDROME

Everything about this disorder seems clouded in uncertainty. Despite a number of anatomic studies suggesting its etiology, the exact cause of the condition remains obscure. Some authors consider the disorder to be quite common, whereas others dispute its existence. Except for those rare cases of documented vascular involvement, the diagnosis is difficult to establish with any assurance, because in most cases, the symptoms are only related to pain (possibly neural). The available electrical tests are also of debatable benefit, and even MRI is not helpful. The standard clinical tests (such as Adson’s) are not specific, and the results of both surgical and medical management are also variable and difficult to measure. Most patients with neural symptoms consistent with thoracic outlet syndrome deserve an extended trial of conservative treatment. Surgery should probably be reserved for those with obvious vascular involvement or those emotionally stable patients whose symptoms cannot be explained on the basis of other causes of arm pain. The variety of surgical approaches also attests to the uncertainty and a complication rate as high as 30 %to 40% has been reported in many series.

COMMON MYTHS AND MISCONCEPTIONS

Venous Disease in Orthopedics

EPIDEMIOLOGY

CLINICAL FEATURES

Superficial thrombophlebitis typically presents with erythema, tenderness, and increased warmth over the involved section of vein. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) of the lower extremity usually presents with swelling, erythema, warmth, increased tissue trugor, and sometimes tenderness distal to the occlusion. A major concern regarding DVT formation is the possible movement of the thrombus or a large fragment of it to the heart, resulting in a pulmonary embolism, a potentially fatal condition! Another possible complication of a DVT is development of chronic venous insufficiency (CVI). Patients with CVI often complain that the involved leg(s) has(have) a dull ache exacerbated by prolonged standing and relieved with elevation of the affected leg. Varicose veins usually present with the patient complaining of a dull ache or sensation of pressure in either the area around the varicosities or in the lower extremity. The symptoms usually resolve with leg elevation. Patients with lymphedema complain of progressive swelling and heaviness of the lower extremity with standing and near-complete resolution when the patient arises from sleeping. Lymphedema can be difficult to distinguish from CVI.

TREATMENT AND PREVENTION

Superficial venous thrombosis can usually be treated by supportive measures, including warm compresses to the affected area, elevation, and NSAIDs for analgesia. NSAIDs should be used cautiously because they may cover propagation of the thrombus. Another concern is the progression of a thrombus in the greater saphenous vein of the thigh near the junction of the saphenofemoral veins. Because this junction gives access to the deep venous system, allowing for the potential development of a pulmonary embolism, anticoagulation therapy should be considered.

Abrams SA. Nutritional rickets: an old disease returns. Nutr Rev. 2002;60:111-115.

Adams JE. Dialysis bone disease. Semin Dial. 2002;15:277-289.

Bloomberg MH. Orthopedic braces. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1964.

Blount WP. Don’t throw away the cane. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1956;38-A:695-708.

Brunicardi FC, et al. Schwartz’s principles of surgery, ed 8. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005.

Crandall C. Risedronate: a clinical review. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:353-360.

DiBenedette V. Keeping pace with many forms of walking. Phys Sports Med. 1988;16:145.

Disability evaluation under Social Security. Chicago: American Medical Association, 1969.

Epperson LW. The late effects of poliomyelitis. Ala J Med Sci. 1988;25:173-177.

Fuster V, Alexander WA, O’Rourke RA, et al. Hurst’s the heart, ed 11. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

Greene WB. Infantile tibia vara. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;1:130-143.

Gross RH. Leg length discrepancy: how much is too much? Orthopedics. 1978;1:307-310.

Hanley EN. Lumbar spine fusions: matching expectations and outcomes. AAOS Bulletin. 1993:6-7.

Junqueria LC, Caneiro J. Basic histology: text and atlas, ed 11. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005.

Levenson JL. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:1137-1145.

Lin JT, Lane JM. Bisphosphonates. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11:1-4.

Line RL, Rust GS. Acute exertional rhabdomyolysis. Am Fam Physician. 1995;52:502-506.

Maynard FM. Post-polio sequelae—differential diagnosis and management. Orthopedics. 1985;8:857-861.

McAdams TR, Swenson DR, Miller RA. Frostbite: an orthopedic perspective. Am J Orthop. 1999;28:21-26.

Merkow RL, Lane JM. Paget’s disease of bone. Orthop Clin North Am. 1990;21:171-189.

Morley AJ. Knock-knee in children. BMJ. 1957;2:976-979.

Nickel VL. Orthopedic rehabilitation. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1982.

Roos DB. Edgar J. Poth Lecture. Thoracic outlet syndromes: update 1987. Am J Surg. 1987;154:568-573.

Rusk HA. Rehabilitation medicine, ed 4. St. Louis: CV Mosby Co., 1977.

Sauret JM, Marinides G, Wang GK. Rhabdomyolysis. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:907-912.

Sherman M. Physiologic bowing of the legs. South Med J. 1960;53:830-836.

Staheli LT. Rotational problems in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:939-950.

Tachdjian MO. Pediatric orthopedics. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co, 1972.

Theriault RL, Hortobagyi GN. The evolving role of bisphosphonates. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:284-290.

Thorsteinsson G. Management of postpolio syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:627-638.

Weber KL. What’s new in musculoskeletal oncology. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1400-1410.