CHAPTER 72 Spastic Dysfunction of the Elbow

CEREBRAL PALSY

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a nonprogressive perinatal injury to the developing central nervous system (CNS). CP produces motor dysfunction, movement disorders, weakness, and impaired function.36 The incidence of CP is 1 to 7 per 1000 children worldwide, and 2 to 3 per 1000 in developed countries.33 The incidence has been fairly constant over the past 40 years; a lesser incidence due to improved prenatal and perinatal care, balanced with a greater incidence of enhanced survival of the very preterm births, has lead to a net constant incidence over time.7

The etiology of CP has been described as a causal pathway with a sequence of conditions culminating in injury to the CNS. A recent 15-year review of the incidence of CP determined that risk factors for preterm infants were periventricular leukomalacia (magnetic resonance imaging evidence of brain structural changes), prolonged rupture of membranes, and patent ductus arteriosus. Risk factors for infants with a gestational age of greater than 34 weeks included size small for gestational age, neonatal transfer (patient transfer at birth from the hospital where they were delivered to a hospital with higher levels of care), and a history of sepsis or meningitis.39

CP is most commonly classified by its anatomic distribution (Box 72-1). Diplegic refers to involvement of both lower extremities. Hemiplegic is involvement of one upper and one lower extremity on the same side. Triplegic is involvement of one upper and both lower extremities. Quadriplegic is involvement of all four limbs. The type of muscle tone is attributed to manifestations of CNS dysfunction and further classifies the disorder to include spasticity, dystonia (athetosis), flaccidity, or mixed patterns.

BOX 72-1 Simple Classification of Cerebral Palsy

Geographic Distribution

*Hemiplegia: principally one-sided (one arm, one leg)

Diplegia: principally lower extremity involvement (two legs)

Life priorities for individuals with CP differ due to their motor system disabilities. According to Bleck, the top four self-reported life priorities for individuals with CP were, in order of importance, (1) communication with others; (2) ability to perform activities of daily living, particularly personal hygiene; (3) mobility in the community; and (4) walking.2 As our society becomes more technologically sophisticated, use of the upper extremities becomes more critical. Care of the patient with CP has shifted toward an increased emphasis on improved upper extremity use.

DIAGNOSIS

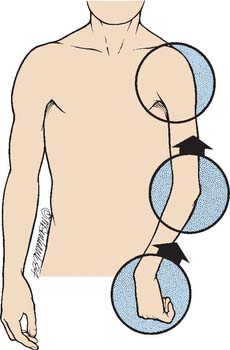

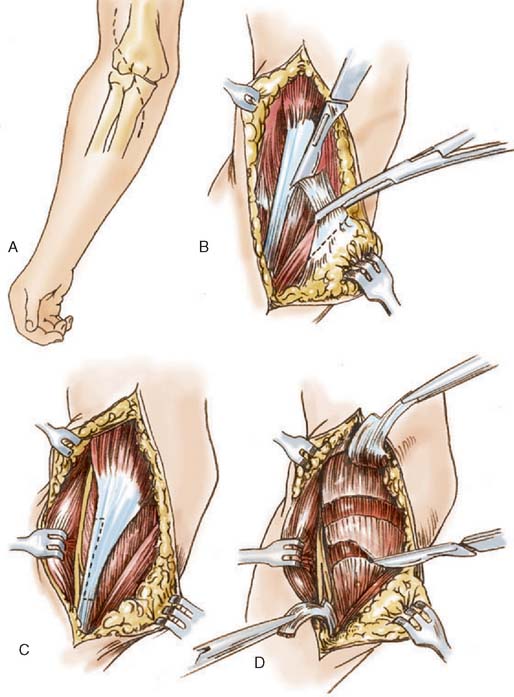

CP is a disorder of the CNS that manifests itself in peripheral motor dysfunction and joint malpositioning. In spastic hemiplegia due to CP, the most common peripheral manifestations in the upper limb are shoulder internal rotation, elbow flexion, forearm pronation, wrist flexion/ulnar deviation, finger clenching (flexor spasticity), swan-necking, and thumb-in-palm deformity, as shown in Figure 72-1. Increased muscle spasticity causes muscle imbalance across joints, which initially leads to impaired function and eventually causes joint contractures with skeletal deformity. The typical elbow deformity of CP is elbow flexion and forearm pronation. Occasionally, it results in posterior dislocation of the radial head,32 which requires no treatment unless in adult life it results in a painful bursa; then the radial head may be excised. Flexion-supination contractures of the elbow can occur but are rare in CP.

CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

Physical examination includes assessment of passive range of motion, active range of motion, muscle tone/control, and overall function of the limb (including hand function assessment). The limb is first examined for passive range of motion of the shoulder, elbow, forearm, wrist, and hand, evaluating for joint and muscle contractures. Even if only the elbow is to be treated, the shoulder, forearm, wrist, and hand need to be assessed because they are essential for the individual to effectively use the upper limb. Muscle tone is noted through the passive evaluation of joint mobility. Passive range of motion needs to be done slowly to overcome muscle spasticity with gentle sustained resistance. Assessment for muscle and joint contracture by passive mobility of the joint and passive stretch of the muscle is performed. The tightness and contracture of some of the muscles around the elbow can be easily palpated, particularly the biceps, brachialis, brachioradialis, and pronator teres.

DEFINITION OF GOALS

In the past, sensory deficiencies of the hand were believed to be a contraindication to surgery in CP. If tested carefully, sensory deficiencies are present in nearly all children with CP.42 Several recent studies have shown that impaired sensation is not a contraindication to surgical intervention in the patient with CP.6,8,42 Appropriate consultation or multispecialty approach to care should be considered before considering surgical intervention. Several alternatives to surgical intervention exist and should be considered. Exploration of the treatment pros and cons may require discussions that include the rehabilitation physicians, neurologists, and neurosurgeons to adequately explore the options of tone reducing medications (diazepam [Valium], baclofen), tone-reducing injections (botulinum toxin, phenol), tone-reducing neurosurgery interventions (selective dorsal rhizotomy), or therapy interventions (splinting, stretching programs). At many institutions, a spasticity management team of specialists is involved with patient evaluation for tone-reducing interventions, and helps guide the orthopedic surgeon as to other treatment alternatives.

TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY

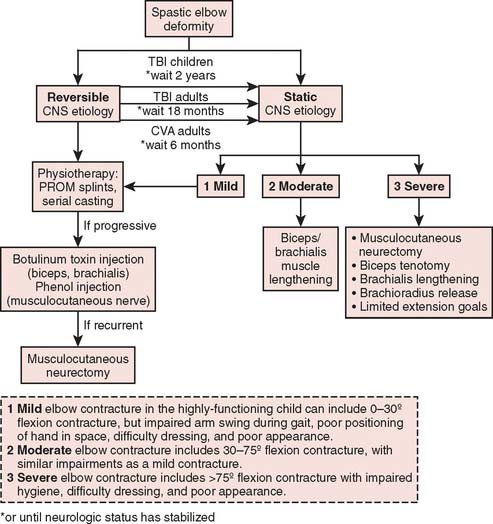

Most often, brain damage acquired in childhood is the result of trauma. The associated spasticity usually does not reach its maximum point until 1 to 2 months after the incident; then muscle tone may gradually decrease during the next 2 years.22,23

Irreversible surgical procedures should not be performed in children with acquired brain damage in the first 2 years after the insult. During this period, serial casting or splinting can be combined with botulinum toxin or phenol injections to deal with elbows with significant flexor tone. Another problem in children with acquired brain injury is heterotopic bone formation, usually about the anterior aspect of the elbow.35 Unlike adults, most children eventually resorb the heterotopic bone. Therefore, we recommend gentle motion and re-evaluation at least 6 months before any attempt is made at excision.

STROKE AND HEAD TRAUMA IN ADULTS

Stroke and head trauma produce permanent impairment in approximately 3 million adults in the United States. Abnormal elbow function due to spasticity and loss of motor control is a common disability. The surgeon treating these conditions must be fully cognizant of the complex rehabilitation process after CNS illness, particularly hand rehabilitation. Surgery is undertaken only after careful assessment of the many factors that determine the patient’s potential to use the limb.3

Substantial neurologic recovery generally follows strokes and head injury. In stroke patients, most neurologic recovery is completed in the first 6 months; in head trauma, patients’ substantial recovery extends over the first year and a half.17 Definitive surgical procedures to improve function are deferred until after the patient’s neurologic condition has stabilized and he or she has learned to cope with the disability and has received appropriate nonoperative therapy.

Prevention of elbow muscle and joint contractures is paramount. Nonoperative therapy should include passive range of motion, splints, and serial casts; if progressive elbow flexion deformity develops before neurologic recovery, then botulinum toxin of the biceps and brachialis or phenol injection of the musculocutaneous nerve is performed.13 Elbow flexion contracture due to spasticity is the most common problem that ultimately requires surgical attention, because it commonly affects patients with nonfunctional hands. Surgery is indicated to correct contracture deformities that interfere with hygiene or cause pain; rarely, it is used to improve cosmesis. Operative intervention is usually deferred until neurologic recovery is complete, which is in 6 to 18 months.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

Dynamic electromyography19,38,41 is becoming increasingly useful because it enables surgeons to determine more precisely which flexor muscles are responsible for a deformity (Fig. 72-2) or whether surgical ablation of a given muscle will be effective.26 Kozin et al reports its use in distinguishing spasticity patterns of the brachioradialis, biceps, and brachialis. This information is particularly valuable for patients with functional elbow motion because it enables the surgeon to release or lengthen only the muscles most involved and to preserve those that are less involved. Slow and fast volitional elbow flexion and extension are assessed. Attempts to move the elbow rapidly enhance an abnormal flexor response.

Last, preoperative evaluation always includes a detailed assessment by a therapist and/or cooperation with a spasticity management team: evaluation of motor and perceptual function of the elbow, hand, and shoulder and examination of cognitive, vocational, and social factors that are important determinants of arm function and treatment goals.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Treatment of the spastic elbow includes several options. If the deformity is not fixed, and the major goal is reduced muscle tone to improve joint position and function, the elbow flexor tone can be diminished by several methods. Tone-reducing medications (Valium, baclofen) would be indicated if the overall global tone is severely affected; consultation with a neurologist or rehabilitation specialist to initiate this treatment would be indicated. Mild elbow contractures can be diminished by range-of-motion stretches and elbow splinting; referral to a physical or occupational therapist to initiate this treatment would be indicated.1

Tone reduction specifically localized to the elbow can be achieved through the use of botulinum toxin injections, and phenol injections; a more permanent tone reduction can be achieved with neurectomy or muscle-lengthening procedures. Muscle-lengthening procedures are the most common surgical procedure performed in the elbow for CP. In order to reduce the flexion posturing of the elbow, lengthening of the biceps and brachialis would be indicated. If the flexion posturing includes pronation deformity of the forearm with wrist flexion and finger flexion posturing, then a flexor pronator slide would be indicated.

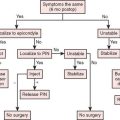

As shown in Figure 72-3, timing of surgical intervention is critical and depends on the presenting diagnosis. Because spasticity develops as a consequence of an upper motor neuron dysfunction in the CNS, it is imperative that neurologic recovery is complete before definitive surgical interventions are performed. Botulinum toxin injections and phenol injections are often recommended as temporary measures during neurologic return, or as interventions in the growing child with worsening contractures. Definitive surgical procedures include musculocutaneous neurectomy or elbow muscle lengthenings of the biceps, brachialis, or brachioradialis muscles or flexor pronator slide. Heterotopic ossification of the elbow can occur with traumatic brain injury or stroke, and is discussed as well.

BOTULINUM TOXIN INJECTIONS

Botulinum toxins (Botox, Allergan Pharmaceuticals, Irvine, CA) are protein products of Clostridium botulinum, and are potent neuromuscular paralyzing agents. Botulinum toxin type A is a related protein that can be used therapeutically in minute doses to block the release of acetylcholine to functionally denervate portions of the muscle causing a localized, dose-related weakness, with little or no systemic absorption of the toxin.30,40 Botulinum toxin has been used to control tone in upper extremities.5 It gives temporary benefits that may help therapists and may be most beneficial to head-injured children.38

TECHNIQUE

Clinical application for decreasing elbow tone spasticity has been described using doses of 5 to 10 units/kg for all muscles injected, using 3 to 5 units/kg for the biceps and brachialis.44 Dilution of the medication in 1 to 5 mL of normal saline helps spread the medication through the muscle belly. Most commonly, a neuromuscular stimulator is used to localize the injection close to motor endplates.25

RESULTS

Wallen et al44 reported improved goals (dressing, arm at side), decreased elbow tone, and good parent/patient satisfaction in 16 children, with a return to baseline by 6 months in most measures. Chen4 measured decreased elbow flexor spasticity within 2 weeks after injection. A recent meta-analysis45 of 12 studies (three randomized controlled and nine uncontrolled) showed that, although some reports measured decreased spasticity, increased range of motion, or increased functional activities, there was either insufficient evidence or insufficient tools to predictably measure reduced spasticity or increased range of motion or improved upper limb function after treatment with botulinum toxin type A injections.

PHENOL INJECTIONS

RESULTS

Garland et al13 described 13 phenol injections in 12 patients for treatment of elbow spasticity at 4.5 months after closed head trauma. The preinjection elbow flexion contractures averaging 55 degrees improved on average 43 degrees when combined with serial casting; all elbows had less than a 20-degree contracture. After neurologic recovery was complete, two elbows went on to other elbow surgical procedures for spasticity.

Keenan et al21 reported on 23 elbows in 17 brain-injured adults treated with percutaneous phenol blocks of the musculocutaneous nerve to control elbow spasticity. Ninety-three percent of patients responded with an improvement of resting elbow flexion from 120 degrees of flexion to 69 degrees of flexion. The mean duration of the block was 5 months.

NEURECTOMY

Musculocutaneous neurectomy is performed only in nonfunctional upper extremities with an elbow flexion contracture interfering with positioning or hygiene. Even when minimal or no fixed myostatic or joint contracture is present, spasticity may force the elbow into a flexed posture that interferes with function. When hemiplegics walk, it is common for the elbow to assume a flexed posture and it may bounce up and down because of clonus. The patient may purposely walk slowly to decrease clonus. Musculocutaneous neurectomy improves cosmesis and eliminates clonus.16 After musculocutaneous neurectomy, the loss of elbow flexion strength is not important, because most stroke patients with excessive elbow flexion have nonfunctional hands.

If elbow contracture exists due to tone alone (usually less than 30 degrees), then partial neurectomy would most commonly improve elbow positioning. If contracture exists in the muscle or joint, then additional serial casting or muscle-lengthening procedures may be necessary to improve elbow extension. A lidocaine (Xylocaine) block of the musculocutaneous nerve along the medial proximal border of the biceps is helpful for separating the effects of flexor tone from those of contracture. Contracture should be expected to ensue when the spastic posture has been present for years. The lidocaine block also predicts brachioradialis elbow flexion capability after neurectomy.

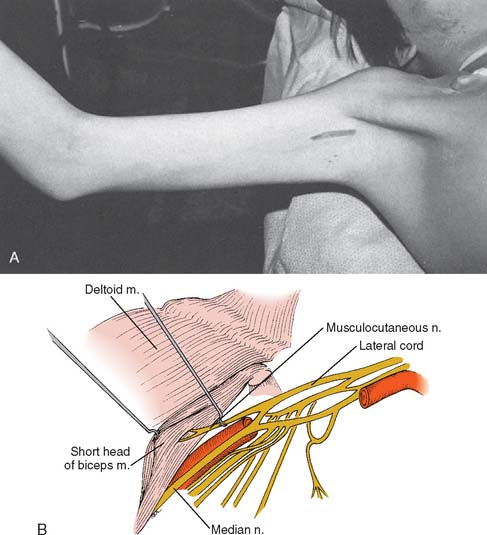

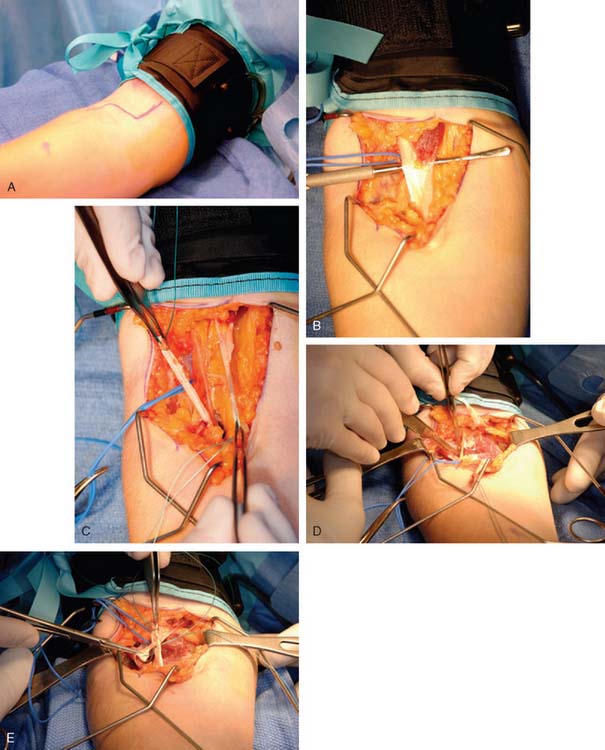

TECHNIQUE

A longitudinal incision is made beginning at the insertion of the pectoralis major muscle in the interval between the biceps (short head) and the coracobrachialis, as shown in Figure 72-4. The biceps and lateral cord of the brachial plexus are located. The musculocutaneous nerve arises from the lateral cord and needs to be identified separate from the median nerve. The nerve is identified before it enters the biceps and confirmed by nerve stimulation. A 1-cm section of the nerve is excised. The wound is closed. The elbow is then splinted in maximum extension.16

RESULTS

A large series of 75 elbows in 52 patients treated at an average age of 9.5 years old using a selective motor fasciculotomy of the musculocutaneous nerve reports follow-up at 1.5 years.34 Total relief of spasticity was achieved in 63% of patients and partial relief in 37%. The authors recommend the procedure as safe, effective, and long lasting.

Garland et al16 report on 30 musculocutaneous neurectomies in 29 patients with a nonfunctional upper extremity due to cerbrovascular accident (59%) or head injury (24%). The goals of the surgery were to improve personal hygiene, ambulation (arm swing), and appearance. Patients with a 30-degree contracture preoperatively did not require postoperative casting; patients with a 30 to 75 degree flexion contracture preoperatively required postoperative casting; and patients with greater than 75-degree flexion contracture preoperatively required concomitant muscle releases with postoperative casting. Twenty-eight patients were successfully treated. Other studies have reported similar results.27,37

BICEPS-BRACHIALIS LENGTHENING

Biceps-brachialis lengthening is the most common surgical procedure used in the treatment of elbow spasticity. Goals of the surgery are to improve passive and active elbow extension. In the highly functional patient with 30- to 60-degree contracture, this procedure improves gait by allowing the arm to come to the side for swing, improves ease of dressing, and improves cosmesis. In the low-functioning patient with greater than 60 degree contracture, this procedure is done primarily for hygiene; in this case, achievement of full extension is not necessary.24 When deformity is long standing and myostatic contracture considerable, biceps tenotomy can be performed.

TECHNIQUE

Mital29 performs biceps-brachialis lengthenings through a curved antecubital approach (Fig. 72-5). The lacertus fibrosus is excised, and Z-plasty of the biceps tendon and release of the brachialis aponeurosis are performed. Most commonly, a correction of 30 to 40 degrees is obtained. If near–full extension is achieved, as shown in Figure 72-6, then no further release is necessary. Further correction can be obtained by release of the origin of the brachioradialis, and/or partial myotomy of the brachialis. In long-standing contractures of greater than 60 degrees, further elbow extension is blocked by contracture of the neurovascular structures and skin. Excessive tension on the neurovascular elements is unnecessary and can lead to vascular compromise. It is not usually necessary to release the anterior capsule. If this procedure is performed on nonfunctional limbs, full extension is not necessary and surgery in combination with postoperative serial casting provides adequate correction. A period of 4 weeks of postoperative immobilization, followed by bivalved elbow splinting, is recommended.

RESULTS

Mital29 has the largest series in the literature, reporting on 32 elbows in 26 patients. Preoperative flexion contracture averaged 48 degrees (range 30 to 60 degrees); postoperative flexion contracture averaged 10 degrees (range 0 to 15 degrees). Average age at the time of surgery was 12 (range 6 to 19 years). Eleven of his patients were quadriplegic, and 15 were hemiplegic. He describes preoperative complaints of excessive dynamic elbow flexion that occurred with excitement or gait, and was a source of frustration and embarrassment. He describes improved gait, improved positioning of the arm, and improved cosmesis in these highly functioning patients. Koman24 describes use of this procedure for more severely involved patients with greater than a 60 degree elbow flexion contracture without specific results reported.

Manske28 describes a similar procedure with incision of the lacertus fibrosis, lengthening of the brachialis fascia, and stripping of the biceps tendon (without Z-lengthening). For 42 elbows in 40 patients, he reports improved dynamic posturing of the elbow from 104 degrees preoperatively to 55 degrees postoperatively. Functional use, as well as aesthetics of the limb, was improved.

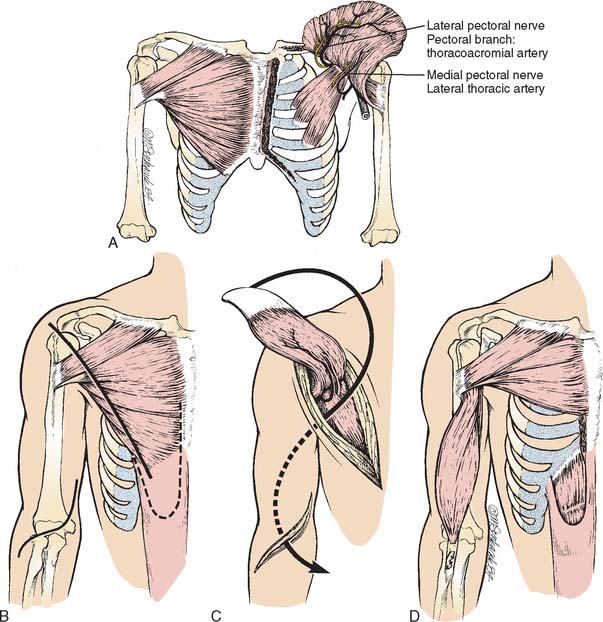

FLEXOR-PRONATOR SLIDE

RESULTS

Pinzur31 reports on the use of the flexor pronator slide in combination with a Z-lengthening of the flexor pollicus longus tendon for treatment of the spastic hand in the adult after stroke. All patients improved two functional levels following the surgery. White46 described the use of the flexor pronator slide in 27 patients, using a concomitant wrist arthrodesis in 12 patients. No comment was made regarding effect on elbow function; wrist and hand function was good in 10, fair in 11, and poor in 11. Poor results were seen in the patients with poor drive, poor intelligence, and poor motor control. Inglis et al18 reported on 18 patients treated at an average age of 19 (range 12 to 45 years old) for severe spastic contractures of the wrist and hand that were not actively or passively correctable. At an average of 17 months after surgery, there were no recurrences of flexion deformities of the wrist and hand. The patients with mild contractures of the elbow were noted to be “improved,” and in the six patients with severe elbow contractures, release of the brachialis fascia was performed concomitantly. Use of the flexor pronator slide is focused primarily on treatment of the hand spastic dysfunction, with gains in elbow spasticity seen only as a secondary effect.

HETEROTOPIC OSSIFICATION

Heterotopic ossification of the elbow, a severe complication that occurs in about 3% of head-injured patients, is discussed in detail in Chapter 31, but is also relevant in the context of this chapter. It most commonly occurs when hypertonus at the elbow is severe because of rigidity from decorticate or decerebrate posturing or spastic hemiplegia (Fig. 72-7). In general, heterotopic ossification is apparent within the first 6 months after head trauma (peak occurrence 2 months). The typical stroke patient infrequently develops heterotopic ossification. With head injury, the complication occurs more often posterior than anterior.11

The incidence of traumatic heterotopic ossification in combined head and elbow injuries is 90%.14 Heterotopic ossification most often affects the collateral ligaments but can form in any planes about the elbow. Bone formation in the ulnar collateral ligament may contribute to an acute ulnar palsy from the localized swelling or delayed ulnar palsy resulting from long-standing pressure.20

Treatment of heterotopic ossification begins with prompt recognition of the condition. Joint motion is preserved by range-of-motion exercises. Movement should be slow to minimize pain. Elbow splints are useful to position the elbow in maximal extension. Diphosphonate therapy is controversial. Indocin, for 3 months, may be used alone or in combination with diphosphonates.9 Oral spasmolytic agents or phenol injection of the musculocutaneous nerve may help to reduce muscle tone in the biceps and brachialis muscles. Temporary reduction of elbow flexor tone permits the therapist to perform range-of-motion exercises more easily to maintain elbow extension. Forceful manipulation of the elbow under anesthesia also may help to maintain or increase elbow range.15

Because heterotopic ossification is so prevalent with combined head and elbow injuries, some type of prophylaxis seems warranted. This type of heterotopic ossification is not related to the severity of the head injury, and joint spasticity may not be present. Resection of heterotopic ossification is performed after the bone is skeletally mature.10–1235 Active motion is essential to maintaining joint range after surgery. Indocin or radiation may be used for prophylaxis.9

1 Barus D., Kozin S.H. The evaluation and treatment of elbow dysfunction secondary to spasticity and paralysis. J. Hand Ther. 2006;19:192.

2 Bleck E.E. Orthopedic Management of Cerebral Palsy. London: Mac Keith Press, 1987.

3 Caldwell C., Braun R.M. Spasticity in the upper extremity. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1974:80-91.

4 Chen J.J., Wu Y.N., Huang S.C., Lee H.M., Wang Y.L. The use of a portable muscle tone measurement device to measure the effects of botulinum toxin type a on elbow flexor spasticity. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2005;86:1655.

5 Corry I.S., Cosgrove A.P., Walsh E.G., McClean D., Graham H.K. Botulinum toxin A in the hemiplegic upper limb: a double-blind trial. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 1997;39:185.

6 Dahlin L.B., Komoto-Tufvesson Y., Salgeback S. Surgery of the spastic hand in cerebral palsy. Improvement in stereognosis and hand function after surgery. J. Hand Surg. [Br.]. 1998;23:334.

7 Drougia A., Giapros V., Krallis N., Theocharis P., Nikaki A., Tzoufi M., Andronikou S. Incidence and risk factors for cerebral palsy in infants with perinatal problems: a 15-year review. Early Hum. Dev. 2007;83:541.

8 Eliasson A.C., Ekholm C., Carlstedt T. Hand function in children with cerebral palsy after upper-limb tendon transfer and muscle release. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 1998;40:612.

9 Garland D.E. A clinical perspective on common forms of acquired heterotopic ossification. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1991;263:13.

10 Garland D.E. Surgical approaches for resection of heterotopic ossification in traumatic brain-injured adults. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1991;263:59-70.

11 Garland D.E., Blum C.E., Waters R.L. Periarticular heterotopic ossification in head-injured adults. Incidence and location. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1980;62:1143.

12 Garland D.E., Hanscom D.A., Keenan M.A., Smith C., Moore T. Resection of heterotopic ossification in the adult with head trauma. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1985;67:1261.

13 Garland D.E., Lucie R.S., Waters R.L. Current uses of open phenol nerve block for adult acquired spasticity. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1982;165:217.

14 Garland D.E., O’Hollaren R.M. Fractures and dislocations about the elbow in the head-injured adult. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1982;168:38-41.

15 Garland D.E., Razza B.E., Waters R.L. Forceful joint manipulation in head-injured adults with heterotopic ossification. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1982;169:133.

16 Garland D.E., Thompson R., Waters R.L. Musculocutaneous neurectomy for spastic elbow flexion in non-functional upper extremities in adults. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1980;62:108.

17 Garland D.E., Waters R.L. Orthopedic evaluation in hemiplegic stroke. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 1978;9:291.

18 Inglis A.E., Cooper W. Release of the flexor-pronator origin for flexion deformities of the hand and wrist in spastic paralysis. J. Bone Joint Surg. [Am.]. 1966;48:847.

19 Keenan M.A., Haider T.T., Stone L.R. Dynamic electromyography to assess elbow spasticity. J. Hand Surg. [Am.]. 1990;15:607.

20 Keenan M.A., Kauffman D.L., Garland D.E., Smith C. Late ulnar neuropathy in the brain-injured adult. J. Hand Surg. [Am.]. 1988;13:120.

21 Keenan M.A.E., Thomas E., Stone L. Percutaneous phenol block of musculocutaneous deformity in cerebral palsy. J. Bone Joint Surg. [Am.]. 1990;15:236.

22 Klonoff H., Clark C., Klonoff P.S. Long-term outcome of head injuries: a 23 year follow up study of children with head injuries. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1993;56:410.

23 Koelfen W., Freund M., Dinter D., Schmidt B., Koenig S., Schultze C. Long-term follow up of children with head injuries classified as “good recovery” using the Glasgow Outcome Scale: neurological, neuropsychological and magnetic resonance imaging results. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1997;156:230.

24 Koman L.A., Gelberman R.H., Toby E.B., Poehling G.G. Cerebral palsy. Management of the upper extremity. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1990;253:62.

25 Koman L.A., Mooney J.F., Smith B.P., Goodman A., Mulvaney T. Management of spasticity in cerebral palsy with Botulinum-A toxin: Report of a preliminary randomized double-blind trial. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1994;14:299.

26 Kozin S.H., Keenan M.H. Using dynamic electromyography to guide surgical treatment of the spastic upper extremity in the brain-injured patient. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1993;288:109.

27 Maarrawi J., Mertens P., Luaute J., Vial C., Chardonnet N., Cosson M., Sindou M. Long-term functional results of selective peripheral neurotomy for the treatment of spastic upper limb: prospective study in 31 patients. J. Neurosurg. 2006;104:215.

28 Manske P.R., Langewisch K.R., Strecker W.B., Albrecht M.M. Anterior elbow release of spastic elbow deformity in children with cerebral palsy. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2001;21:772.

29 Mital M.A. Lengthening of the elbow flexors in cerebral palsy. J. Bone Joint Surg. [Am.]. 1979;61:515.

30 National Institutes of Health. Clinical use of botulinum toxin. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement, November 12-14, 1990. Arch. Neurol. 1991;48:1294.

31 Pinzur M.S. Flexor origin release and functional prehension in adult spastic hand deformity. J. Hand Surg. [Br.]. 1991;16:133.

32 Pletcher D.F., Hoffer M.M., Koffman D.M. Non-traumatic dislocation of the radial head in cerebral palsy. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1976;58:104.

33 Praemer A., Furner S., Rice D.P. Musculoskeletal Conditions in the United States. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 1999.

34 Purohit A.K., Raju B.S., Kumar K.S., Mallikarjun K.D. Selective musculocutaneous fasciculotomy for spastic elbow in cerebral palsy: A preliminary study. Acta Neurochir. (Wien). 1998;140:473.

35 Roberts J.B., Pankratz D.G. The surgical treat-ment of heterotopic ossification at the elbow following long-term coma. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1979;61:760.

36 Samilson R.L. Principles of assessment of the upper limb in cerebral palsy. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1966;47:105.

37 Sindou M.P., Simon F., Mertens P., Decq P. Selective peripheral neurotomy (SPN) for spasticity in childhood. Childs. Nerv. Syst. 2007;23:957.

38 Spaulding S.J., White S.C., McPherson J.J., Schild R., Transon C., Barsamian P. Electromyographic analysis of reach in individuals with cerebral palsy. Electromyogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1990;30:109.

39 Stanley F., Blair E., Alberman E. Cerebral Palsies: Epidemiology and Causal Pathways. London: Mac Keith Press, 2000.

40 Van Heest A.E. Applications of Botulinum toxin in orthopaedics and upper extremity surgery. Tech. Hand Up. Extrem. Surg. 1997;1:27.

41 Van Heest A. Functional assessment aided by laboratory studies. Hand Clin. 2003;19:565.

42 Van Heest A.E., House J.H., Cariellol C. Upper extremity surgical treatment of cerebral palsy. J. Hand Surg. [Am.]. 1999;24:323.

43 Van Heest A.E., House J., Putnam M. Sensibility deficiencies in the hands of children with spastic hemiplegia. J. Hand Surg. [Am.]. 1993;18:278.

44 Wallen M.A., O’Flaherty S.J., Waugh M.C. Functional outcomes of intramuscular botulinum toxin type A in the upper limbs of children with cerebral palsy: a phase II trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2004;85:192.

45 Wasiak J., Hoare B., Wallen M. Botulinum toxin A as an adjunct to treatment in the management of the upper limb in children with spastic cerebral palsy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2004. CD003469

46 White W.F. Flexor muscle slide in the spastic hand: the Max Page operation. J. Bone Joint Surg. [Br.]. 1972;54:453.