9 Sonography for Trauma

• Focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) is sensitive and specific for the detection of intraperitoneal free fluid, but it has poor results when used in an attempt to localize solid organ injury.

• The indications for FAST have expanded to include the evaluation of patients with normotensive blunt trauma and penetrating trauma.

• FAST can be learned quickly by most emergency physicians, although its chief limitation is that it is operator dependent.

FAST Examination

Literature Review

Multiple studies have demonstrated the utility of FAST for the evaluation of patients after blunt abdominal trauma. One of the first studies to highlight FAST by EPs was performed by Ma and Mateer in 1995. This study evaluated ultrasound for detection of free fluid not only in the peritoneum but also in the pericardium, the retroperitoneal space, and the pleural cavity. The authors evaluated a total of 975 cavities and calculated a sensitivity of 90%, a specificity of 99%, and an accuracy of 99%.1 This study demonstrated that with training, EPs are capable of identifying free fluid with high sensitivity and specificity.

Subsequent studies focusing on FAST have found variable results ranging from sensitivities of 79% to 100% and specificities of 95.6% to 100%.2–5 Although calculated sensitivities and specificities have been variable across studies, one finding that seems consistent is that both sensitivity and specificity appear to increase in hypotensive patients.6

Conversely, a Cochran review published in 2005 found “insufficient evidence from RCTs [randomized controlled trials] to justify promotion of ultrasound-based clinical pathways in diagnosing patients with suspected blunt abdominal trauma.”7 These findings have been controversial, and a similar literature review by Melniker found “the FAST examination, adequately completed, is a nearly perfect test for predicting a ‘Need for OR’ in patients with blunt torso trauma.”8

One finding that has appeared consistently in most studies is that although FAST is sensitive and specific for the detection of intraperitoneal free fluid, it has poor results when used in attempts to localize solid organ injury.9,10

Ultrasound has been shown to be a reliable study for the evaluation of traumatic pericardial effusions. Mandavia et al. found that EPs with training in echocardiography had a sensitivity of 96%, a specificity of 98%, and an overall accuracy of 97.5% for this indication.11

How to Perform a FAST Examination

A low-frequency transducer is typically used to ensure proper depth of penetration.

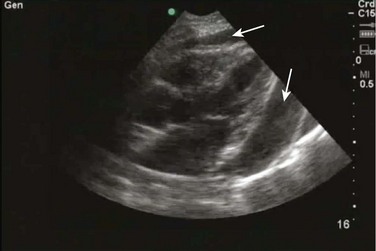

Subxiphoid View

To evaluate the subxiphoid view of the heart, the transducer is placed just below the subxiphoid process and aimed toward the patient’s left shoulder (Fig. 9.1). It is frequently necessary to apply some pressure to the upper part of the patient’s abdomen to enable the sonographer to look “up” into the patient’s chest. It is also helpful to think of the transducer as a flashlight and imagine shining it toward the left side of the patient’s chest. Another helpful tip for beginning sonographers is to increase the depth if at first the heart is not seen in full. A four-chamber view of the heart should be sought (Fig. 9.2). Specifically, the bright white (or hyperechoic) outline of the pericardium should be sought to evaluate for the presence of pericardial effusion.

Right Upper Quadrant

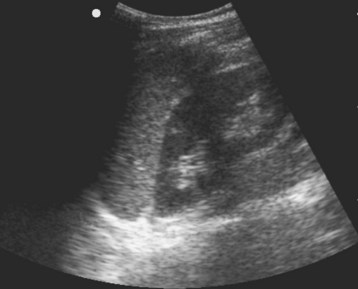

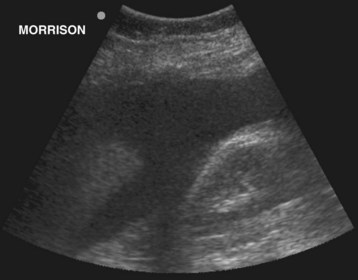

The right upper quadrant should be evaluated in both the coronal and transverse planes. To begin, the transducer is placed on the patient’s midaxillary line between the 8th and 11th ribs (Fig. 9.3). This position should be adjusted as needed to overcome rib shadowing and to obtain the best image possible. Aiming the indicator toward the patient’s head will yield a coronal image. The interface between the liver and kidney (pouch of Morison) and the potential spaces around this area should be thoroughly evaluated for the presence of free fluid (Fig. 9.4). This can be done by sweeping the transducer anteriorly and posteriorly. Moving the transducer superiorly a rib space or two will usually allow a view of the echogenic diaphragm curving over the dome of the liver. The area superior to the diaphragm, the costophrenic recess, can be evaluated for the presence of pleural fluid as well. Once a coronal image has been obtained, the transducer should be rotated so that the indicator points toward the patient’s right to obtain a transverse view. Although such placement frequently provides an adequate view, it is often helpful to angle the transducer on a slightly oblique plane so that it fits into the intercostal space and thus limits rib shadowing. Once the liver and kidney are seen, sweeping the transducer superiorly and inferiorly offers a full evaluation of areas in which free fluid may collect.

Left Upper Quadrant

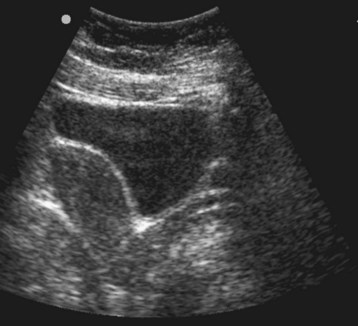

The left upper quadrant is evaluated in much the same manner as the right upper quadrant. One important distinction is that the left kidney is usually found in a more posterior and superior location. Therefore, to obtain a coronal image, the transducer is placed in the posterior midaxillary line between the 8th and 11th ribs (Fig. 9.5). The indicator should be pointing toward the patient’s head. It is particularly important not only to evaluate the interface between the kidney and spleen but also to seek the interface between the spleen and diaphragm (Fig. 9.6). This aids in viewing the costophrenic recess for free pleural fluid, as well as the subphrenic recess, where free peritoneal fluid frequently collects. Again, once the coronal view has been obtained, the transducer should be swept anteriorly and posteriorly to fully assess the left upper quadrant. After the coronal plane has been viewed, the transducer should be rotated so that the indicator faces the patient’s right. It may be helpful to place the transducer at a slight angle to avoid any artifact created by the ribs. Once the interface between the kidney and spleen is found, the transducer should be swept inferiorly and posteriorly to evaluate this region in full.

Pelvis

The final component of the basic FAST examination is evaluation of the pelvis. The transducer should be placed just superior to the pubic symphysis. Beginning in the transverse plane, the indicator on the transducer should be facing toward the patient’s right (Fig. 9.7). The bladder is easily identified in this orientation as a rectangularly shaped object filled with dark, anechoic urine, especially if the ultrasound can be performed before placement of a urinary catheter (Fig. 9.8). Although the bladder is generally identified quickly, the evaluation should proceed further and the bladder be used as an acoustic window to view the dependent portions of the pelvis. This can be done by tilting the transducer toward the patient’s feet and back upward or more superiorly. The transducer can then be rotated toward the patient’s head to view the same area in a sagittal orientation (Fig. 9.9). In this plane the bladder has a triangular appearance (Fig. 9.10). Complete evaluation of the potential spaces of the pelvis can be achieved by tilting the transducer from side to side.

Normal and Abnormal Findings

When evaluating the subxiphoid view of the heart, the bright white, echogenic outline of the pericardium should be sought (see Fig. 9.2). Normally, the pericardium should closely abut the ventricle. Free fluid will be seen as a black collection between the pericardium and the ventricles of the heart (Fig. 9.11). Typically, fluid will first accumulate in the most dependent part of the pericardial sac and can thus be seen deep to the left ventricle. It should be noted that the amount of fluid seen may appear underwhelming on first inspection. It is important to realize that a smaller amount of fluid is needed to cause cardiac tamponade in a trauma patient. This is due to the rapid accumulation of free fluid within the pericardial sac, which quickly overcomes the ability of the fibers of the pericardium to stretch to accommodate increasing pressure.

In the right upper quadrant, free fluid most commonly accumulates in the area between the liver and kidney (pouch of Morison). Acute hemorrhage will be seen as an anechoic (black) stripe of varying size in this potential space (Fig. 9.12).

Free fluid in the left upper quadrant appears much the same as in the right upper quadrant. It may appear as an anechoic stripe between the spleen and kidney. However, the potential space between the spleen and the diaphragm is a common location for free fluid to accumulate and may be overlooked without careful evaluation (Figs. 9.13 and 9.14).

In the pelvis, free fluid will accumulate in the gutters surrounding the bladder (Fig. 9.15). The bladder can be distinguished from free fluid by noting the rectangular shape of the bladder. Free fluid is amorphous and will appear to seep into the gutters of the pelvis, whereas the bladder is either a rectangular (transverse) or triangular (sagittal) shape, depending on the imaging plane chosen.

E-FAST Examination

Literature Review

Ultrasound of the chest shows potential as a rapid tool for diagnosing the presence of pleural fluid and pneumothorax. A prospective study of 240 trauma patients was retrospectively analyzed and published by Ma and Meteer in 1997. This study found an overall sensitivity of 96.2%, specificity of 100%, and accuracy of 99.6% for detection of hemothorax. Interestingly, the authors concluded that “Ultrasonography is comparable to the initial chest radiograph for accuracy in detection of hemothorax” and that its use may result in more rapid diagnosis in trauma patients.12 Similarly, the use of ultrasound for detection of pneumothorax has also yielded positive results, with multiple studies reporting a range of sensitivities from 95.3% to 100% and specificities from 78% to 99.2%.13–15 Specifically, the study of Blaivas et al. evaluated ultrasound and supine chest radiography head to head and found ultrasound to have higher sensitivity (98.1% for ultrasound versus 75.5% for chest radiography) and similar specificity (99.2% for ultrasound versus 100% for chest radiography).15

Ultrasound of the IVC has also been examined as an indirect measure of central venous pressure (CVP). A study by Randazzo et al. in 2008 compared CVP estimated by EPs using ultrasound of the IVC with that determined by cardiologists using formal echocardiography. Overall, they found a 70.2% rate of agreement, with most agreement occurring in patients with high CVP (83.3%).16 A later study by Nagdev et al. in 2010 compared the caval index (percent collapse of the IVC with inspiration) with CVP measured directly with an indwelling catheter and found that a caval index of greater than 50% was 91% sensitive and 94% specific in predicting a CVP of less than 8 mm Hg.17 Both the overall size of the IVC and the percentage of collapse with inspiration have also been found to correlate with blood loss, an important finding in trauma patients.18,19

How to Scan and Scanning Protocols

The lungs and pleural recesses can be evaluated for the presence of fluid, such as occurs with hemothorax, and for the presence of pneumothorax. The pleural recesses should be viewed while the right and left upper quadrants of the abdomen are viewed in the coronal orientation as part of the traditional FAST examination. Moving the transducer more superiorly, from the 8th through the 11th rib interspaces to the 6th to 9th rib interspaces, will usually allow a clear image of the bright white, echogenic diaphragm arcing over the liver or spleen (Fig. 9.16). To the left of the diaphragm, the costophrenic recess can be studied for the presence of fluid.

The IVC can be viewed as it courses behind the liver toward the right atrium. The size and movement of the IVC can be used to estimate the overall fluid status of the patient. Again using a low-frequency transducer to obtain adequate depth of penetration, the IVC is typically best seen in the epigastric area. The transducer should be placed in a sagittal orientation, just to the patient’s right, with the indicator pointing toward the patient’s head. Tilting the transducer toward the patient’s head will best use the liver as an acoustic window. The IVC can be seen as a longitudinal tube terminating in the right atrium of the heart (Fig. 9.17). It should be evaluated for overall size and for changes with respiration.

Normal and Abnormal Findings

A pleural effusion is typically seen from the costodiaphragmatic recesses as an anechoic (black) fluid collection superior to the diaphragm (Fig. 9.18). This is in contrast to a normal lung, which will appear as a hazy, ill-defined area superior to the diaphragm. The hazy appearance is caused by the presence of the normally air-filled lungs.

No set “normal” definition of the IVC has be established. Rather, both its size and percent collapse are situated on a spectrum, depending on the patient’s overall intravascular fluid status (Videos 3 and 4). Table 9.1 summarizes the relationship between IVC size and percent collapse with respiration correlated with CVP. These findings are applicable to trauma patients when attempting to establish their overall stability. A patient with a finding of low CVP following blunt abdominal trauma may cause the EP to be more aggressive in resuscitation or more cautious in delaying definitive management.

Table 9.1 Summary of the Relationship Between the Size and Percent Collapse of the Inferior Vena Cava and Central Venous Pressure

| IVC SIZE | CHANGE WITH INSPIRATION (%) | CENTRAL VENOUS PRESSURE |

|---|---|---|

| <1.5 cm | Total collapse | 0-5 cm |

| 1.5-2.5 cm | >50% collapse | 5-10 cm |

| 1.5-2.5 cm | <50% collapse | 11-15 cm |

| >2.5 cm | <50% collapse | 16-20 cm |

| >2.5 cm | No change | >20 cm |

IVC, Inferior vena cava.

Video of the interface between the visceral and parietal pleura demonstrating the “slide sign.”

Video of the IVC before fluid resuscitation.

The overall size of the IVC is small and there is nearly complete collapse with respiration.

Video of the IVC after fluid resuscitation.

The IVC now appears larger and does not collapse with respiration.

Blaivas M, Lyon M, Sandeep D. A prospective comparison of supine chest radiography and bedside ultrasound for the diagnosis of traumatic pneumothorax. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:844–849.

Ma OJ, Mateer JR, Ogata M, et al. Prospective analysis of a rapid trauma ultrasound examination performed by emergency physicians. J Trauma. 1995;38:879–888.

Melniker LA. The value of focused assessment with sonography in trauma examination for the need for operative intervention in blunt torso trauma: a rebuttal to “emergency-ultrasound–based algorithms for diagnosing blunt abdominal trauma (review),” from the Cochrane Collaboration. Crit Ultra J. 2009;1:73–78.

Stengel D, Bauwens K, Sehouli J, et al. Emergency-ultrasound–based algorithms for diagnosing blunt abdominal trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2005. CD0044446

1 Ma OJ, Mateer JR, Ogata M, et al. Prospective analysis of a rapid trauma ultrasound examination performed by emergency physicians. J Trauma. 1995;38:879–885.

2 Healey M, Simons RK, Winchell RJ, et al. A prospective evaluation of abdominal ultrasound in trauma: is it useful? J Trauma. 1996;40:875–885.

3 Boulanger BR, McLellan BA, Brenneman FD, et al. Emergent abdominal sonography as a screening test in a new diagnostic algorithm for blunt trauma. J Trauma. 1996;40:867–874.

4 Rozycki GS, Ochsner MG, Jaffin JH, et al. Prospective evaluation of surgeon’s use of ultrasound in the evaluation of trauma patients. J Trauma. 1993;34:516–527.

5 Rozycki GS, Ballard RB, Feliciano DV, et al. Surgeon performed ultrasound for the assessment of truncal injuries: lessons learned from 1540 patients. Ann Surg. 1998;228:557–567.

6 Lee BC, Ormsby EL, McGahan JP, et al. The utility of sonography for the triage of blunt abdominal trauma to exploratory laparotomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:415–421.

7 Stengel D, Bauwens K, Sehouli J, et al. Emergency-ultrasound–based algorithms for diagnosing blunt abdominal trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2005. CD0044446

8 Melniker LA. The value of focused assessment with sonography in trauma examination for the need for operative intervention in blunt torso trauma: a rebuttal to “emergency-ultrasound–based algorithms for diagnosing blunt abdominal trauma (review),” from the Cochrane Collaboration. Crit Ultra J. 2009;1:73–84.

9 Chiu WC, Cushing BM, Rodriguez A, et al. Abdominal injuries without hemoperitoneum: a potential limitation of focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST). J Trauma. 1997;42:617–625.

10 Kendall JL, Faragher J, Hewitt GJ, et al. Emergency department ultrasound is not a sensitive detector of solid organ injury. West J Emerg Med. 2009;10:1–5.

11 Madavia DP, Hoffner RJ, Mahaney K, et al. Bedside echocardiography by emergency physicians. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38:377–382.

12 Ma OJ, Mateer JR. Trauma ultrasound examination versus chest radiography in the detection of hemothorax. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;29:312–316.

13 Lichtenstein DA, Meziere G, Lascois N, et al. Ultrasound diagnosis of occult pneumothorax. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1231–1238.

14 Lichtenstein DA, Menu Y. A bedside ultrasound ruling out pneumothorax in the critically ill: lung sliding. Chest. 1995;108:1345–1348.

15 Blaivas M, Lyon M, Sandeep D. A prospective comparison of supine chest radiography and bedside ultrasound for the diagnosis of traumatic pneumothorax. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:844–849.

16 Randazzo MR, Snoey ER, Levitt MA, et al. Accuracy of emergency physician assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction and central venous pressure using echocardiography. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;10:973–977.

17 Nagdev AD, Merchant RC, Tirado-Gonzalez A, et al. Emergency department bedside ultrasonographic measurement of the caval index for noninvasive determination of low central venous pressure. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:290–295.

18 Lyon M, Blaivas M, Brannam L. Sonographic measurement of the inferior vena cava as a marker of blood loss. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:45–50.

19 Yanagawa Y, Nishi K, Sakamoto T, et al. Early diagnosis of hypovolemic shock by sonographic measurement of inferior vena cava in trauma patients. J Trauma. 2005;58:825–829.