52 Solid tumours

Epidemiology

Prostate cancer is now the most common cancer in men (24%) followed by lung (15%) and bowel (14%) cancer. In women, breast cancer is the most common (31%) followed by bowel (12%) then lung (12%). However, there are regional variations. From 1979 to 2008, mortality rates from cancer fell by 20% (Cancer Research UK, 2010).

Aetiology

Environmental factors

Increasingly, lifestyle factors play a large part in the development of many cancers. Cigarette smoking has been identified as the single most important cause of preventable disease and premature death in the UK. The beneficial effect of stopping smoking on the cumulative risk of death from lung cancer reduces with increasing age (Doll et al., 2004). Smoking causes about 90% of lung cancer deaths, and the link between tobacco and cancer was established more than 50 years ago.

Table 52.1 lists a number of other factors which have been associated with cancer development.

Table 52.1 A–K of factors associated with specific cancer sites: An empirical basis for recommending lifestyle changes (Jankowski and Boulton, 2005)

| Factor | Associated cancer |

|---|---|

| Alcohol consumption >3 units a day | Most squamous cancers, especially bladder and oesophagus |

| Body mass index >25 and certainly >30 | All solid cancers |

| Cigarette smoking at any level (even passive smoking) | Bladder, lung, head and neck, oesophagus and oropharyngeal cancers |

| Diet, especially one that is high in fat | All solid cancers |

| Exercising <30 min a day | All solid cancers |

| Family history of cancer (in at least one first-degree relative and at least three people in two or more generations) | Inherited cancer syndromes, including breast, colorectal, diffuse gastric, ovarian, prostate and uterine cancers |

| Genital and sexual health (sexually transmitted infections) | Cervical cancer |

| Health-promoting drugs that may decrease global cancer risks (but need a careful risk/benefit analysis) | Colonic adenomas can be treated with low-dose aspirin but can have serious side effects Hormone replacement therapy linked with breast cancer |

| Intense sunburn | Melanoma |

| Job-related factors | Lung cancer (exposure to asbestos and particulates), skin cancer (contact with arsenic) |

| Known disease associations | Colorectal cancer has predisposing mucosal pathology – adenomas, coeliac disease, ulcerative colitis |

Genetic factors

A number of rare tumours are known to be associated with an inherited predisposition, where an individual is born with a marked susceptibility to cancer. This is due to the inheritance of a single genetic mutation which may be sufficient to greatly increase the risk of one or more types of cancer. Examples include the paediatric malignancies, Wilms’ tumour of the kidney and bilateral retinoblastoma, a rare cancer of the eye. Some common cancers such as breast, ovarian and colorectal cancer may also show a tendency to occur in families, but these represent a small proportion of the overall presentation of common cancers where identifiable risk factors are relevant in only 5–10% of cases, although when the genetic factor is present the cancers tend to have their onset at a younger age (Garber and Offit, 2005).

Screening and prevention

Chemoprevention

Another potential future development is the effect of aspirin as a chemopreventive agent for colorectal cancer. Maximal effect requires long-term use of high-dose aspirin that may increase the risk of gastro-intestinal bleeding. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors may also be candidates for chemoprevention. However, the regular use of these drugs may also cause gastro-intestinal bleeding and increase the risk of cardiovascular events (Herszényi et al., 2008)

Cancer at the cellular level

Tumour suppressor genes

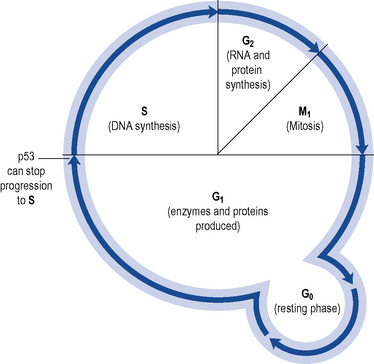

The p53 protein acts as a regulator of cell growth and proliferation and controls passage from G1 to S phase in cell division (see Fig. 52.1). Agents which damage DNA cause p53 to accumulate. This accumulation of p53 switches off replication in the cell, arresting the cell cycle and allowing time to repair. If repair fails, p53 may trigger cell suicide by apoptosis. Thus, p53 controls and halts the proliferation of abnormal cell growth.

Tumour growth

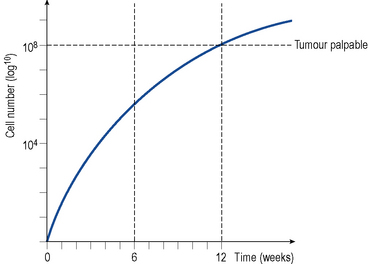

A solid tumour represents a population of dividing and non-dividing cells. The time it takes for a tumour mass to double is known as the doubling time. The latter will vary depending on the type of tumour but for most solid tumours it is about 2–3 months. In most solid tumours, the growth rate is very rapid initially (exponential growth) and then slows as the tumour increases in size and age, a pattern described as Gompertzian growth (see Fig. 52.2). The growth fraction is the percentage of actively dividing cells in the tumour, and this decreases with increasing tumour size.

Patient management

Clinical assessment

Tumour markers

Tumour markers are usually proteins associated with a malignancy and are clinically useful to:

They may be detected in a solid tumour, in circulating tumour cells in peripheral blood, in lymph nodes, in bone marrow or in other body fluids. A number of the tumour markers are presented in Table 52.2.

Table 52.2 Examples of tumour markers used in detection, diagnosis and monitoring

| Tumour marker | Indicative cancer |

|---|---|

| CA125 | Ovarian cancer, although non-specific |

| α-Fetoprotein (AFP) | Testicular tumour |

| β-Human chorionic gonadotrophin (β-HCG) | |

| 5-Hydroxyindole acetic acid (5HIAA) | Carcinoid tumours |

| Thyroglobulin | Thyroid cancer |

| α-Fetoprotein | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Prostate-specific antigen | Prostate cancer |

| Human chorionic gonadotropin | Gestational trophoblastic tumours |

Staging investigations

Since the cancer is often disseminated at the time of presentation, it is vital that patients undergo thorough staging investigations to establish the extent and nature of disease. This will determine the most appropriate treatment offered to the patient. Baseline investigations range from clinical examination, blood tests, liver function tests, diagnostic imaging such as chest and skeletal X-rays, ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET), depending on the disease type and likely pattern of spread. Clinical guidelines for staging and management of malignancies of the various body systems have been produced at local and national level in most developed countries, with relatively minor variations according to local custom and practice (e.g. NICE in UK, see http://www.nice.org.uk/ for guidance and NCI in USA, see http://www.cancer.gov/ for guidance).

Staging classification

Most tumours are classified according to the TNM (tumour–nodes–metastases) system where T (0–4) indicates the size of the primary tumour, N (0–3) the extent of lymph node involvement and M (0–1) the presence or absence of distant metastases. Each solid tumour site has a specific grading and staging classification such as Dukes staging in colorectal cancer (Cancer Research UK, 2009) and Gleason scoring for grading prostate cancer (Berney, 2007).

Performance status

The patient’s general level of fitness (performance status) at the time of diagnosis is often a surprisingly reliable indicator of prognosis independent of disease-related factors, and will help determine if they are likely to withstand intensive chemotherapy; this therefore influences the choice of treatment. A number of physical rating scales have been devised to assess performance status, including the Karnofsky performance index (Karnofsky and Burchenal, 1949) and the World Health Organization (WHO) performance scale (Box 52.1).

Box 52.1 Performance status scales

100 Normal, no complaints, no evidence of disease

90 Able to carry on normal activity, minor signs or symptoms of disease

80 Normal activity with effort, some signs or symptoms of disease

70 Cares for self, unable to carry on normal activity or do active work

60 Requires occasional assistance but is able to care for most of own needs

50 Requires considerable assistance and frequent medical care

40 Disabled, requires special care and assistance

30 Severely disabled, hospitalisation is indicated, although death is not imminent

20 Very sick, hospitalisation necessary, active supportive treatment is necessary

Prognostic factors

These are factors that can predict how the disease is likely to behave and determine an outcome in individual patients. For example, Table 52.3 lists prognostic factors in patients with colorectal cancer.

Table 52.3 Prognostic factors in patients with colorectal cancer

| Favourable | Unfavourable |

|---|---|

| Good performance status | Presence of nodal involvement |

| No penetration of the tumour through the bowel wall | Presence of distant metastases |

| Absence of nodal involvement | Bowel obstruction and bowel perforation |

| Absence of distant metastases |

Treatment

Treatment goals

Role of radiotherapy

Radiotherapy can be used to cure cancer, reduce the symptoms of the tumour, reduce the size of the tumour ready for surgery or to prevent re-occurrence of the tumour after surgical removal. It can be used alone or in combination with surgery and/or chemotherapy. A full exposition of the role of radiotherapy is beyond the scope of this chapter, which concentrates on the role of systemic agents. However, the combination of radiotherapy and systemic treatment is becoming increasingly employed as research shows the benefit to disease control and long-term survival, for example, in carcinoma of the uterine cervix (Green et al., 2009).

Cytotoxic chemotherapy

Chemotherapy regimen

Chemotherapy scheduling

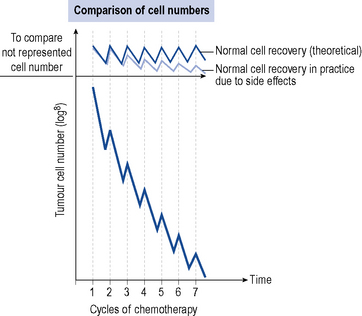

Figure 52.3 demonstrates the tumour cell kill for each cycle of chemotherapy together with the healthy normal cell kill. Chemotherapy works in situations where the healthy normal cells recover faster or more completely from the effects of chemotherapy compared to the tumour cells. This allows the tumour cells to be progressively killed off, whilst not having a detrimental effect on the patient.

Chemotherapy dose

The dose of most chemotherapy agents is calculated using the patient’s body surface area (BSA) and is usually given in the form of milligrams per square meter. Body surface area may be calculated from the height and weight of the patient using a nomogram and may need to be recalculated for subsequent cycles of chemotherapy if the patient experiences significant weight changes. Table 52.4 gives an example of a chemotherapy regimen used in breast cancer. The reliability of body surface area as a predictor of the effective safe dose is diminished for patients who are either very thin (cachectic) or grossly overweight (morbidly obese) since it does not then reflect a reasonable estimate of lean body mass.

Table 52.4 Example of a chemotherapy regimen FEC–T (Fluorouracil, epirubicin, cyclophosphamide, docetaxel (Taxotere®)) for breast cancer

| Indication | Adjuvant Breast Cancer | |

|---|---|---|

| Length of cycle | 21 days | |

| No. of cycles | 3 cycles of FEC followed by 3 cycles of Taxotere® (Docetaxel) | |

| FEC | ||

| Fluorouracil | IVB | 500 mg/m2 day 1 |

| Epirubicin | IVB | 100 mg/m2 day 1 |

| Cyclophosphamide | IVB | 500 mg/m2 day 1 |

| T | ||

| Docetaxel | IVI over 1 h | 100 mg/m2 day 1 |

IVB, i.v. bolus; IVI, i.v. infusion.

Adjuvant chemotherapy

In colorectal cancer, for example, adjuvant chemotherapy provides significant disease-free survival benefit by reducing the recurrence rate and also increases overall survival. This indicates the curative role of chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting (Sargent et al., 2009). Similarly, in breast cancer, adjuvant treatment has been shown to increase recurrence-free survival (Levine and Whelan, 2006), and trials are underway to determine which agents and in what combination further improvements in overall survival will be obtained. A recent trial has shown that three-weekly AC/T (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, docetaxel [Taxotere®]) is significantly inferior to CEF (cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, 5-flourouricil) or EC/T (epirubicin, cyclophosphamide, docetaxel [Taxotere®]) in terms of recurrence-free survival (Burnell et al., 2010). This is important, as standard treatment choices should move to the superior regimen.

Synchronous chemoradiation

In several cancers, chemotherapy alongside radical radiotherapy is now established. Agents such as cisplatin are commonly used as a ‘radiosensitiser’ in head and neck, oesophageal and cervical cancers. The use of cetuximab in combination with radiotherapy for a certain type of head and neck cancer is also recommended (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2008). Although common, the use of the term ‘radiosensitiser’ in this context is somewhat inaccurate and is distinct from the ‘true’ radiosensitising drugs such as nimorazole, which interact at a chemical level with very short-lived radiation-induced free radicals, and the effect is better termed ‘combined modality therapy’.

Targeted therapies

Epidermal growth factor receptor

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

Angiogenesis is the formation of new blood vessels on which tumour growth depends. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is key in angiogenesis and its overexpression has been associated with increased vasculature, aggressive disease and poor prognosis. The monoclonal antibody bevacizumab inhibits VEGF, thereby reducing new blood vessel growth and interstitial pressure within the tumour, allowing improved chemotherapy access. Studies have demonstrated meaningful survival benefits when bevacizumab is administered in conjunction with chemotherapy in patients with advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer (Hurwitz et al., 2004).

Human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2

Overexpression of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) is associated with a particularly aggressive form of breast cancer (about 20% cases are HER2 positive) linked with a poor prognosis. Trastuzumab, a humanised monoclonal antibody, specifically targets human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 and is only effective in patients with elevated levels. It is used widely in metastatic and early breast cancer (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2002, 2006a). The use of trastuzumab in other cancers that express human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 is also under investigation. Trastuzumab has also been licensed for use in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 positive gastric cancer.

Capecitabine

Capecitabine is a fluoropyrimidine carbamate precursor of 5-fluorouracil (5FU). Given orally, it is converted via enzyme pathways to 5-fluorouracil. As these enzymes are found in higher concentrations in tumour cells, treatment is effectively targeted. Capecitabine has been shown to be at least as effective as intravenous 5-fluorouracil (Twelves et al., 2008), and it is widely used in practice. This is of a particular benefit where the total regimen can then be given orally rather than intravenously.

Management of patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy

Prescription verification

Over recent years, there has been considerable effort to improve the quality and safety of chemotherapy services for adult patients (National Chemotherapy Advisory Group, 2009). In particular, the importance of all chemotherapy prescriptions being checked by appropriately trained and competent pharmacists is now recognised. A checklist of key points an authorised pharmacist must undertake to verify any prescription for systemic anti-cancer therapy prior to preparation and release has been determined (British Oncology Pharmacy Association, 2010) and is presented in Box 52.2.

Box 52.2 Standards for chemotherapy prescription verification (British Oncology Pharmacy Association, 2010)

Dose modification or delay

Appropriate investigations must be carried out before each treatment to ensure that patients are fit for chemotherapy. In particular, the patient’s haematological, renal and hepatic function should be investigated. For some cytotoxic drugs, it may be necessary to adjust the dose, or even stop treatment, in the presence of renal or hepatic impairment to ensure that delayed excretion or reduced metabolism does not result in excess toxicity. Therefore, the individual summary of product characteristics (SPC) for the chemotherapy agent should be consulted and can be found at http://www.medicines.org.uk.

Symptom control

Nausea and vomiting

Domiciliary treatment

Oral cytotoxic drugs can safely be taken at home so long as the patient is informed and able to monitor side effects. Availability of a 24-h helpline is essential for these patients should they encounter problems whilst on treatment (National Chemotherapy Advisory Group, 2009). In the future, administration of intravenous treatments, such as the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab, may be carried out more frequently in the home setting, particularly when safety permits and where patient preference becomes an influential factor.

Monitoring anti-cancer therapy

Toxicity

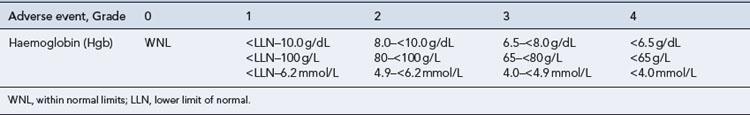

The toxicity resulting from treatment is routinely assessed following each cycle of chemotherapy, and may result in therapy being modified on subsequent cycles, for example, a dose reduction, a delay in treatment or, in some cases, an alternative treatment. A number of international rating scales are available for rating predictable acute reactions arising from chemotherapy, including that of the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (for an example, see Table 52.5). Standardising the assessment of treatment-related toxicity in this way allows comparison to be made between published reports of clinical trials.

Response to treatment

Definitions of response

These have been standardised by the WHO:

Again, this allows comparison of results between different reported studies. An update of the WHO guidelines has been published (Therasse et al., 2000) called RECIST or Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours. To avoid confusion, it is important to stipulate in trial protocols which system will be used. Although clinical response indicates tumour sensitivity, it may not necessarily predict long-term survival nor does it measure other benefits such as quality of life.

Questions

Answers

Answers

Answers

Questions

Answers

Answers

Berney D.M. The case for modifying the Gleason grading system. Br. J. Urol. Int.. 2007;100:725-726.

British Oncology Pharmacy Association. Standards for clinical pharmacy verification of prescriptions for cancer medicines. 2010. Available at http://www.bopawebsite.org/tiki-page.php?pageName=Position+Statements

Burnell M., Levine M.N., Chapman J.A.W., et al. Cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and fluorouracil versus dose-dense epirubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel versus doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel in node-positive or high-risk node-negative breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol.. 2010;28:77-82.

Cancer Research UK. Dukes stages of bowel cancer, Available at. 2009.http://www.cancerhelp.org.uk/type/bowel-cancer/treatment/dukes-stages-of-bowel-cancer.

Cancer Research UK. Cancer in the UK: July 2010 factsheet, Available at. 2010.http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/prod_consump/groups/cr_common/@nre/@sta/documents/generalcontent/018070.pdf.

Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. Common toxicity criteria, Version 2.0. DCTD, NCI, NIH, DHHS, Available at. 1998.http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcv20_4–30–992.pdf.

Doll R., Peto R., Boreham J., et al. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. Br. Med. J.. 2004;328:1519. Available at http://www.bmj.com/content/328/7455/1519.full

Galea M.H., Blamey R.W., Elston C.E., et al. The Nottingham prognostic index in primary breast cancer. Breast Can. Res. Treat.. 1992;22:207-219.

Garber J.E., Offit K. Hereditary cancer predisposition syndromes. J. Clin. Oncol.. 2005;23:276-292.

Green J.A., Kirwan J.J., Tierney J., et al. Concomitant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for cancer of the uterine cervix (Review), The Cochrane Library Issue 4. Available at. 2009.http://www.cochranejournalclub.com/chemoradiotherapy-for-cervical-cancer-clinical/pdf/CD002225_standard.pdf.

Herszényi L., Farinati F., Miheller P., et al. Chemoprevention of colorectal cancer: feasibility in everyday practice? Eur. J. Cancer Prevent.. 2008;17:502-514.

Hurwitz H., Fehrenhacher L., Novotny W., et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. New Engl. J. Med.. 2004;350:2335-2342.

Jankowski J., Boulton E. Cancer prevention. Br. Med. J.. 2005;331:618.

Karnofsky D.A., Burchenal J.H. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In: MacLeod C.M., editor. Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents. New York: Columbia University Press, 1949.

Levine M., Whelan T. Adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer – 30 years later. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2006;355:1920-1922.

National Chemotherapy Advisory Group. Chemotherapy services in England: ensuring quality and safety. London: Department of Health; 2009. Available at http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/DH_104500

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Guidance on the use of trastuzumab for the treatment of advanced breast cancer. London: NICE; 2002. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/advancedbreastcancerno34PDF.pdf

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Trastuzumab for the adjuvant treatment of early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer. London: NICE; 2006. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11586/33458/33458.pdf

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Docetaxel for the treatment of hormone refractory prostate cancer. London: NICE; 2006. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11578/33348/33348.pdf

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Cetuximab for the treatment of locally advance squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. London: NICE; 2008. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/12006/40996/40996.pdf

Piccart-Gebhart M.J., Procter M., Leyland-Jones B., et al. Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer (HERA Study). N. Engl. J. Med.. 2005;353:1659-1672.

Sargent D., Sobrero A., Grothey A., et al. Evidence for cure by adjuvant therapy in colon cancer: observations based on individual patient data from 20,898 patients on 18 randomized trials. J. Clin. Oncol.. 2009;27:872-877.

Therasse P., Arbuck S.G., Eisenhauer E.A., et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumours. J. Natl. Cancer Inst.. 2000;92:205-216.

Twelves C., Scheithauer W., McKendrick J., et al. Capecitabine versus 5-FU/LV in stage III colon cancer: updated 5-year efficacy data from X-ACT trial and preliminary analysis of relationship between hand-foot syndrome (HFS) and efficacy. Gastr. Cancers Symp. Abstr.. 2008:274. Available at http://www.asco.org/ascov2/Meetings/Abstracts?&vmview=abst_detail_view&confID=53&abstractID=10524

Allwood M., Wright P., Stanley A. The Cytotoxics Handbook, fourth ed. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2002.

Department of Health. Chemotherapy Services in England: Ensuring Quality and Safety. A Report from the National Chemotherapy Advisory Group. London: Department of Health; 2009. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_104500

Devita V.T., Lawrence T.S., Rosenberg S.A., et al. DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg’s Cancer – principles and practice of oncology, eighth ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2008.

Smith I., Chua S. ABC of breast diseases. Medical treatment of early breast cancer: adjuvant treatment. Br. Med. J.. 2006;332:34-37.