10 Soft tissue tumours and other diseases

SWELLINGS AND TUMOURS OF SOFT TISSUE

Soft tissue swellings are a common presentation to primary care physicians and a cause of great anxiety to patients when they discover a lump in their limb or trunk which they interpret as a cancer. In fact malignant tumours are very rare and benign tumours are much more common in a ratio of more than 100:1. These tumours frequently cause problems in diagnosis and treatment because of the difficulty in differentiating them from other, much commoner, causes of lumps and swellings in the limbs. These include cysts and ganglia around joints, normal muscle variants, muscle rupture, haematoma, vascular aneurysm, and myositis ossificans.

Muscle tears

Symptomatic muscle tears are not usually a problem since there is typically a history of trauma and painful onset of swelling. Clinically there is therefore no suggestion that this is a soft tissue mass. However some patients, particularly in an older age group, present with a painless swelling with no clear history of any single incident to account for it. Characteristically this is seen in the anterior thigh. The reason is spontaneous rupture of rectus femoris muscle. The proximal muscle can contract unopposed with a resulting soft tissue mass palpable in the thigh. In cases of clinical doubt an MRI scan will confirm that the swelling is muscle and demonstrate the defect at the site of rupture (see Fig. 18.29, p. 414).

Haematoma

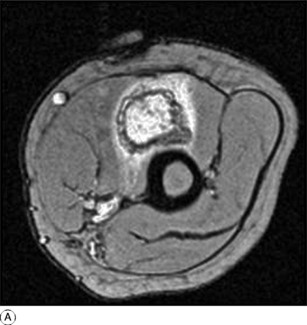

An acute tissue haematoma, whether from injury or post-surgery, should not pose a problem for clinical diagnosis. Difficulty can occur when a large deep haematoma does not resolve and enters a chronic phase that may mimic the swelling from a recurrent lesion. The MRI scan should aid diagnosis showing a peripheral dark rim from the presence of iron-containing haemoglobin breakdown products (Fig. 10.1).

Aneurysm

Occasionally an aneurysm originating from a deep vessel may mimic a soft tissue tumour, but careful clinical examination will normally identify arterial pulsation. Imaging with MR and digital arteriography can confirm the nature of the lesion and the vessel of origin.

Synovial cysts and ganglia

Ganglia are of unknown origin situated typically around joints and contain mucoid tissue. Trauma and synovial herniation are suggested as causative factors. They do not usually have a demonstrable connection with the underlying joint. They are seen most commonly around the wrist and ankle, but also occur near the knee arising from the proximal tibio fibular joint (Fig. 10.2).

Synovial cysts are a synovial lined outpouching which connects with the underlying joint space.

These therefore occur around joints most commonly and are typically seen especially in the knee. Popliteal (Baker’s) cysts (Fig. 18.32A, p. 418) and cysts associated with meniscal tears can present as palpable soft tissue masses. Ultrasound is the easiest method of confirming that these are cystic and not solid lesions.

Myositis ossificans (heterotopic ossification)

This is an uncommon but troublesome lesion because of its apparent malignant behaviour. It presents as a painful and tender lump in a limb muscle, with or without a history of recent trauma to the site. Imaging is crucial to obtain the correct diagnosis and MRI and ultrasound are the most useful in the very early stages as they can detect the presence of calcification in the lesion which is the key to diagnosis (Fig. 10.3A). Later imaging with CT scanning will reveal a diagnostic rim of ossification at the periphery of the well-circumscribed lesion. Plain radiographs after several weeks will show some calcification in the muscle which should indicate the correct diagnosis (Fig. 10.3B). However, in some patients where the early changes are not recognised these appearances may be misinterpreted and may lead to a presumed diagnosis of soft tissue osteosarcoma. This assumption may be reinforced if a biopsy is performed, as this will show a very active lesion containing immature mesenchymal cells with atypical nuclei and osteoid formation. No active treatment is required, other than careful observation, as the lesion will resolve in 2–3 months.

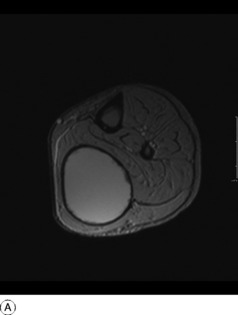

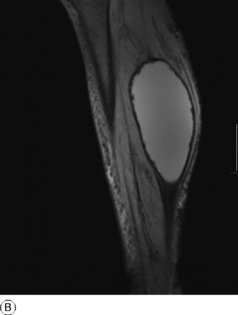

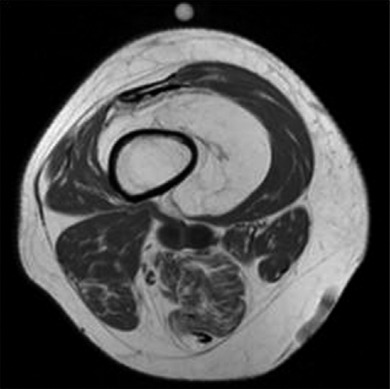

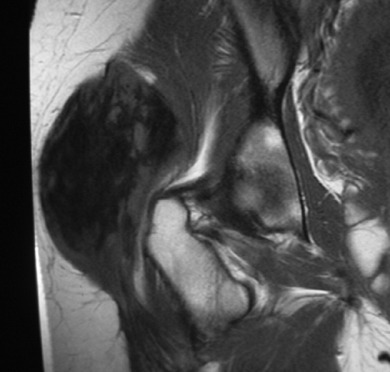

Fig. 10.3 A T2 weighted axial MR scan of the arm with myositis ossificans in the biceps muscle. Inside the mass of high signal there is a ring of low signal representing calcification. MR or ultrasound will detect calcification long before it is visible on plain films. B Radiograph of humerus in the same patient as Fig. 10.3A. This was obtained several weeks after the MR scan and the calcification within the muscle is now evident and a diagnosis of myositis ossificans is most likely.

TUMOURS OF SOFT TISSUE

BENIGN TUMOURS OF SOFT TISSUE

Benign peripheral nerve sheath tumours

Tumours arising from nerves are of two types: schwannomas and neurofibromas.

Schwannoma

These are just a little less common than neurofibromas. They are slow growing and painless with no neurological symptoms. They are typically less than 5 cm in size. The tumour usually lies eccentric to the nerve which is displaced. Surgical excision can thus be undertaken with sparing of the nerve.

Neurofibroma

Histologically the tumour is composed of cellular fibrous tissue arranged in whorls. The tumour may be solitary; but in the condition known as multiple neurofibromatosis (von Recklinghausen’s disease) (p. 70) numerous tumours are associated with pigmented areas in the skin. A neurofibroma growing within the spinal canal is an important cause of compression of the spinal cord or cauda equina.

Imaging with MR scanning can identify the nature of the lesion and sometimes its neural origin (Fig. 10.4).

Lipoma

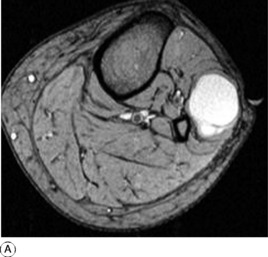

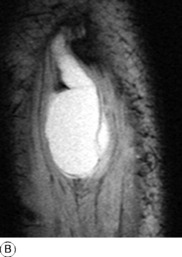

A lipoma is a common tumour that may arise in almost any part of the body. It usually occurs in the subcutaneous tissues, but may also develop more deeply as an intramuscular lesion. It forms a soft, often large, lobulated mass enclosed within a thin capsule. It consists of fat, usually with little connective tissue stroma. When the lesion is deep to fascia and of a large size it may be difficult to differentiate on clinical grounds from malignant liposarcoma. Imaging by MRI may be diagnostic of lipoma if it shows a homogeneous white lesion on the T1 weighted image with the same density as the subcutaneous and intramedullary fat (Fig. 10.5). However where there is less than 75% of fat in the lesion, or if the septation is nodular rather than linear, there is a possibility of malignancy and a biopsy is required prior to surgical excision.

Haemangioma

Imaging by MR scanning shows characteristic clusters of abnormal dilated blood vessels giving a variegated serpiginous appearance.

Musculo-aponeurotic fibromatosis (desmoid tumour)

This rare tumour occurs mostly in young adults as a slowly growing hard swelling in the musculo-aponeurotic tissues, particularly in the trunk and shoulder regions. When it involves the abdominal wall or arises intra-abdominally it is known as an abdominal desmoid tumour. It is important because of its histological resemblance to malignant sarcoma and the characteristic infiltrative growth locally. Imaging by MRI scans will show a variable degree of heterogeneity (Fig. 10.6), which is not diagnostic, but will show the extent of the lesion and any involvement of neuro-vascular structures. Biopsy and histological examination will differentiate it from sarcoma and fortunately it has a more benign course and never metastasises. However, there is a high 30–40% risk of local recurrence, even after radical wide-margin excision, suggesting that it may arise from multicentric foci in the same limb.

MALIGNANT TUMOURS OF SOFT TISSUE

Malignant tumours of soft tissue (soft-tissue sarcomas) are uncommon, comprising 1% of adult malignant neoplasms. Of mesenchymal origin, they arise from connective tissues such as fascia, aponeurosis, tendon sheath, intermuscular septa, voluntary muscle, and synovial membrane. Such a tumour presents difficulties both in diagnosis and in treatment. It may be hard to distinguish from its benign counterpart, presenting as a progressively enlarging but usually painless swelling. It is of firm consistency and may appear to be well localised, though this is usually a false impression. It may spread widely within the soft tissues and the surrounding pseudocapsule forms no barrier. Metastasis occurs through the blood stream, mainly to the lungs.

Investigation of these tumours is aided by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI scans provide good definition of the anatomical extent of the tumour and of its relationship to the neurovascular structures (Fig. 10.7), thereby allowing correct planning of surgical treatment. However the scans cannot reliably differentiate between benign and malignant lesions, which must ultimately depend on expert histological examination from a representative biopsy.

The results of the surgical treatment of most types of soft-tissue sarcoma have been improved by adjuvant therapy with radiation or potent chemotherapeutic agents used in combination as for bone sarcomas. Radiotherapy may be used after operative excision, to reduce the risk of local recurrence, but does not remove the need for adequate surgical treatment, which demands excision with wide margins of healthy tissue rather than simple local excision or enucleation.

Liposarcoma

This is the second commonest of the soft-tissue sarcomas, usually occurring in the deep tissues. It grows as a lobulated mass, usually in the buttock or thigh, and may often attain an enormous size (Fig. 10.8). It has a wide range of behaviour, depending upon its histological appearance and the amount of myxomatous content. Tumours showing predominantly pleomorphic and round cells have a poor prognosis, but the presence of myxoid tissue improves the outlook.

Rhabdomyosarcoma

This rare variety of soft-tissue sarcoma which arises from skeletal muscle occurs mainly in children or young adults. It affects particularly the trunk or lower limbs. It forms a rapidly growing mass. Histologically it is characterised by cells showing longitudinal and cross striations typical of primitive myoblasts. It metastasises early, mainly to the lungs.

OTHER SOFT TISSUE DISEASES

INFLAMMATORY LESIONS OF SOFT TISSUE

Irritative bursitis

This is caused by excessive pressure or friction, occasionally by a gouty deposit. There is a mild inflammatory reaction in the wall of the bursa, and there is usually an effusion of clear fluid within the sac. Examples are the common ‘bunion’ that forms over a prominent metatarsal head in hallux valgus, prepatellar bursitis or ‘housemaid’s knee’, olecranon bursitis (sometimes caused by gout), and subacromial bursitis.

Irritative (frictional) tenosynovitis and peritendinitis

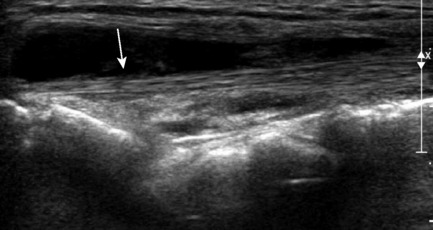

This is caused by excessive friction from over-use. The synovial sheath is mildly inflamed and there is an exudate of watery fluid within it, visible on ultrasound scanning (Fig. 10.9). A similar traumatic inflammation may affect the flimsy paratenon surrounding those tendons that are devoid of synovial sheaths. This is termed paratendinitis and is a common problem around the wrist and hand. The controversial condition known as repetitive stress syndrome comes into this category (p. 327).

Infective tenosynovitis

Bacterial infection of a tendon sheath may be acute or chronic. Acute infective (suppurative) tenosynovitis is caused by an organism of the pyogenic group. There is an acute inflammatory reaction in the wall of the sheath, with a purulent exudate from it. It is an uncommon condition, but it is well recognised in the flexor tendon sheaths in the hand (p. 316).

In chronic bacterial tenosynovitis, also an uncommon lesion in Western countries, the infection is often tuberculous. The synovial wall is much thickened and there is a fibrinous exudate. The flexor sheaths of the forearm and hand are the usual sites (compound palmar ganglion, p. 317).

Tenovaginitis

In tenovaginitis there is a mild chronic inflammation or thickening of the fibrous wall of a tendon sheath as distinct from the synovial lining. The cause is unknown: it is not due to bacterial infection. The only common sites are the mouths of the fibrous flexor sheaths in the fingers or thumb (‘trigger’ finger, p. 329), and the sheaths of the extensor pollicis brevis and abductor pollicis longus tendons at the radial side of the wrist (de Quervain’s syndrome, p. 328).

FIBROMYALGIA (FIBROSITIS)

Fibromyalgia, formerly termed fibrositis, is a clinical rather than a pathological entity. Some deny its existence. Certainly its nature is obscure. Nevertheless the term is a useful label for a common clinical condition that at present lacks a complete explanation. The main features are pain in certain muscles, with tenderness when they are gripped or squeezed. Small firm nodules may be felt. Joint movements are full and there are no other objective signs. The condition is commonest in the muscles of the upper back, especially in the trapezius area, and affects women more frequently than men. There may be associated tiredness, sleep disturbance, and depression. Treatment, if required, is by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication and active exercises.