Chapter 494 Soft Tissue Sarcomas

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Clinical Manifestations

The most common presenting feature of rhabdomyosarcoma is a mass that may or may not be painful. Symptoms are caused by displacement or obstruction of normal structures (Table 494-1). Origin in the nasopharynx may be associated with nasal congestion, mouth breathing, epistaxis, and difficulty with swallowing and chewing. Regional extension into the cranium can produce cranial nerve paralysis, blindness, and signs of increased intracranial pressure with headache and vomiting. When the tumor develops in the face or cheek, there may be swelling, pain, trismus, and, as extension occurs, paralysis of cranial nerves. Tumors in the neck can produce progressive swelling with neurologic symptoms after regional extension. Orbital primary tumors are usually diagnosed early in their course because of associated proptosis, periorbital edema, ptosis, change in visual acuity, and local pain. When the tumor arises in the middle ear, the most common early signs are pain, hearing loss, chronic otorrhea, or a mass in the ear canal; extensions of tumor produce cranial nerve paralysis and signs of an intracranial mass on the involved side. An unremitting croupy cough and progressive stridor can accompany rhabdomyosarcoma of the larynx. Because most of these signs and symptoms also are associated with common childhood conditions, clinicians must be alert to the possibility of tumor.

| REGION | SYMPTOMS |

|---|---|

| Head and neck | Asymptomatic mass, may mimic enlarged lymph node |

| Orbit | Proptosis, chemosis, ocular paralysis, eyelid mass |

| Nasopharynx | Snoring, nasal voice, epistaxis, rhinorrhea, local pain, dysphagia, cranial nerve palsies |

| Paranasal sinuses | Swelling, pain, sinusitis, obstruction, epistaxis, cranial nerve palsies |

| Middle ear | Chronic otitis media, hemorrhagic discharge, cranial nerve palsies, extruding polypoid mass |

| Larynx | Hoarseness, irritating cough |

| Trunk | Asymptomatic mass (usually) |

| Biliary tract | Hepatomegaly, jaundice |

| Retroperitoneum | Painless mass, ascites, gastrointestinal or urinary tract obstruction, spinal cord symptoms |

| Bladder/prostate | Hematuria, urinary retention, abdominal mass, constipation |

| Female genital tract | Polypoid vaginal extrusion of mucosanguineous tissue, vulval nodule |

| Male genital tract | Painful or painless scrotal mass |

| Extremity | Painless mass, may be very small but with secondary lymph node involvement |

| Metastatic | Nonspecific symptoms, associated with the diagnosis of leukemia |

From McDowell HP: Update on childhood rhabdomyosarcoma, Arch Dis Child 88:354–357, 2003.

Diagnosis

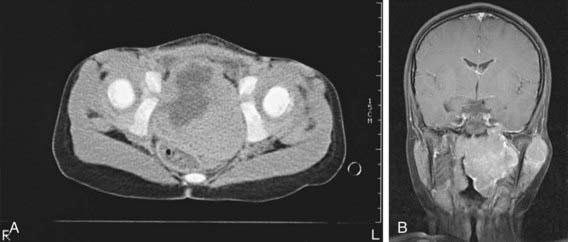

Early diagnosis of rhabdomyosarcoma requires a high index of suspicion. The microscopic appearance that of is of a small round blue cell tumor. Neuroblastoma, lymphoma, and Ewing sarcoma also are small round blue cell tumors. The differential diagnosis depends on the site of presentation. Definitive diagnosis is established by biopsy, microscopic appearance, and results of immunohistochemical stains. A lesion in an extremity may be thought to be a hematoma or hemangioma, an orbital lesion resulting in proptosis may be treated as an orbital cellulitis, or bladder-obstructive symptoms may be missed. Adolescents may ignore paratesticular lesions for a long time. Unfortunately, several months often elapse between the initial symptoms and biopsy. Diagnostic procedures are determined mainly by the area of involvement. CT or MRI is necessary for evaluation of the primary tumor site. With signs and symptoms in the head and neck area, radiographs should be examined for evidence of a tumor mass and for indications of bony erosion. MRI should be performed to identify intracranial extension or meningeal involvement and also to reveal bony involvement or erosion at the base of the skull. For abdominal and pelvic tumors, CT with a contrast agent or MRI can help delineate the tumor (Fig. 494-1). A radionuclide bone scan, chest CT, and bilateral bone marrow aspiration and biopsy should be performed to evaluate the patient for the presence of metastatic disease and to plan treatment. The most critical element of the diagnostic work-up is examination of tumor tissue, which includes the use of special histochemical stains and immunostains. Cytogenetics and molecular genetics may be helpful in detecting specific chromosomal translocations of fusion proteins present in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Lymph nodes also should be sampled for presence of disease spread, especially in tumors of the extremities and in boys >10 yr of age with paratesticular tumors.

Other Soft Tissue Sarcomas

The non-rhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcomas (NRSTSs) constitute a heterogeneous group of tumors that account for 3% of all childhood malignancies (Table 494-2). Because they are relatively rare in children, much of the information about their natural history and treatment has been derived from studies in adult patients. In children, the median age at diagnosis is 12 yr, with a male:female ratio of 2.3:1. These tumors commonly arise in the trunk or lower extremities. The most common histologic types are synovial sarcoma (42%), fibrosarcoma (13%), malignant fibrous histiocytoma (12%), and neurogenic tumors (10%). Molecular genetic studies often prove useful in diagnosis, because several of these tumors have characteristic chromosomal translocations.

Table 494-2 FEATURES OF MOST COMMON TYPES OF NON-RHABDOMYOCARCOMA SOFT TISSUE SARCOMAS

| TISSUE TYPE | TUMOR | NATURAL HISTORY AND BIOLOGY |

|---|---|---|

| Adipose | Liposarcoma | A very rare tumor. Usually arises in the extremities or retroperitoneum; associated with a nonrandom translocation, t(12;16) (q13;p11). Tends to be locally invasive and rarely metastasizes; wide local excision is the treatment of choice. The role of radiation therapy and chemotherapy in treating gross residual or metastatic disease is not established. |

| Fibrous | Fibrosarcoma | Most common soft tissue sarcoma in children <1 yr. Congenital fibrosarcoma is a low-grade malignancy that commonly arises in the extremities or trunk and rarely metastasizes. Surgical excision is treatment of choice; dramatic responses to preoperative chemotherapy may occur. In children >4 yr, the natural history is similar to that in adults (a 5-yr survival rate of 60%); wide surgical excision and preoperative chemotherapy are commonly used. Associated with t(12;15)(p13;q25) or trisomy 11, also +8, +17, +20. |

| Malignant fibrous histiocytoma | Most commonly arises in the trunk and extremities, deep in the subcutaneous layer. Histologically subdivided into storiform, giant cell, myxoid, and angiomatoid variants. The angiomatoid type tends to affect younger patients and is curable with surgical resection alone. Wide surgical excision is the treatment of choice. Chemotherapy has produced objective tumor regressions. | |

| Vascular | Hemangiopericytoma | Often arises in the lower extremities or retroperitoneum; may manifest as hypoglycemia and hypophosphatemic rickets. Both benign and malignant histology. Nonrandom translocations t(12;19) (q13;q13) and t(13;22) (q22;q13.3) have been described. Complete surgical excision is the treatment of choice. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy may produce responses. |

| Angiosarcoma | Rare in children; 33% arise in skin, 25% in soft tissue, and 25% in liver, breast, or bone. Associated with chronic lymphedema and exposure to vinyl chloride in adults. Survival rate is poor (12% at 5 yr) despite some responses to chemotherapy/radiation therapy. | |

| Hemangioendothelioma | Can occur in soft tissue, liver, and lung. Localized lesions have a favorable outcome; lesions in lung and liver often are multifocal and have a poor prognosis. | |

| Peripheral nerves | Neurofibrosarcoma | Also known as the malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Develops in up to 16% of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1); almost 50% occur in patients with NF1. Deletions of chromosome 22q11-q13 or 17q11 and p53 mutations have been reported. Commonly arises in trunk and extremities and is usually locally invasive. Complete surgical excision is necessary for survival; response to chemotherapy is suboptimal. |

| Synovium | Synovial sarcoma | The most common non-rhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcoma in some series. Often manifesting in the 3rd decade, but 33% of patients are <20 yr. Typically arises around the knee or thigh and is characterized by a nonrandom translocation t(X;18) (p11;q11). Wide surgical excision is necessary. Radiation therapy is effective in microscopic residual disease, and ifosfamide-based therapy is active in advanced disease. |

| Unknown | Alveolar soft part sarcoma | Slow-growing tumor; tends to recur or to metastasize to lung and brain years after diagnosis. Often arises in the extremities and head and neck. A myogenic origin has been proposed. Resection of primary and metastatic sites, when possible, is recommended. |

| Smooth muscle | Leiomyosarcoma | Often arises in the gastrointestinal tract and may be associated with a t(12;14) (q14;q23) translocation. Associated with Epstein-Barr virus in immunodeficiency syndromes (including AIDS). Complete surgical excision is the treatment of choice. |

Arndt CAS, Crist WM. Medical progress: common musculoskeletal tumors of childhood and adolescence. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:342-352.

Arndt CAS, Stoner JA, Hawkins DS, et al. Vincristine, actinomycin, and cyclophosphamide compared with vincristine, actinomycin, and cyclophosphamide alternating with vincristine, topotecan, and cyclophosphamide for intermediate-risk rhabdomyosarcoma: children’s oncology group study D9803. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5182-5188.

Crist WM, Anderson JR, Meza JL, et al. Intergroup rhabdomyosarcoma study. IV: results for patients with nonmetastatic disease. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3091-3102.

Hettmer S, Wagers AJ. Uncovering the origins of rhabdomyosarcoma. Nat Med. 2010;16:171-173.

McDowell HP. Update on childhood rhabdomyosarcoma. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:354-357.

Meyer WH, Spunt SL. Soft tissue sarcomas of childhood. Cancer Treat Rev. 2004;30:269-280.

Schaaf G, Hamdi M, Zwijnenburg D, et al. Silencing of SPRY1 triggers complete regression of rhabdomyosarcoma tumors carrying a mutated RAS gene. Cancer Res. 2010;70:762-771.

Sinha S, Peach AHS. Diagnosis and management of soft tissue sarcoma. BMJ. 2011;342:157-162.

Spunt SL, Poquette CA, Hurt YS, et al. Prognostic factors for children and adolescents with surgically resected nonrhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcoma: an analysis of 121 patients treated at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3697-3705.

Stevens MCG. Treatment for childhood rhabdomyosarcoma: the cost of cure. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:77-84.