CHAPTER 55 Soft Tissue Injuries Following Whiplash

INTRODUCTION

Cervical soft tissue injuries resulting from whiplash are often considered controversial. These injuries are presumed to be caused by an acceleration/deceleration injury that commonly occurs during many motor vehicle collisions.1 Although several structures may cause pain following a whiplash injury, patients with whiplash associated disorders (WAD) are often diagnosed as having an acute musculoligamentous injury referred to as a cervical sprain or strain.1–3 The tissues involved in this diagnosis are postulated to be the large, multisegmental muscles, the smaller one- or two-segment muscles, the fascia or connective tissue, and the spinal ligaments. Fortunately, the majority of these whiplash patients improve over time.4–6 However, a subset of patients with whiplash injuries continue to have pain complaints despite a lack of objective diagnostic evidence confirming the presence of an injury.7–9 Although pain generators such as the cervical disc and facet have been described elsewhere,10–14 and may contribute to referred or radicular pain and even cervicogenic headache, many of these patients with WAD have overlying muscular or soft tissue pain that may radiate into the shoulders and upper limb in a nonradicular pattern.8,15–17 Since soft tissue symptoms persist despite what would seem an adequate period of healing and, since abnormal pathology cannot be identified with advanced radiologic or electrophysiological testing, these patients may be diagnosed as malingerers or felt to be seeking financial compensation for their injuries. Yet, some studies have demonstrated that litigation may not be a clear risk factor for the continuance of symptoms.18,19 Therefore, patients are often diagnosed with myofascial pain, the etiology of which also continues to remain elusive and controversial.15,20 Recently, however, there have been theories that may better explain the persistence of these symptoms following whiplash injury.

ACUTE INJURY

Overview

Although there are accepted pain generators of the cervical spine, it is commonly observed following whiplash that the cervical musculoligamentous tissues may contribute to WAD of the cervical spine.1,2,7,8,21,22 The precise biomechanics of cervical whiplash have been discussed elsewhere and are more complex than a simple cantilever mechanism.23,24 However, the cervical acceleration and deceleration that occur during whiplash may help explain injury that is incurred by the supportive tissues. Although the full range of cervical motion is not exceeded during low–moderate cervical whiplash,25–27 it is implied that acceleration of the torso produces relatively forceful head extension. As this occurs, the anterior cervical muscles are lengthened when the acceleration force of the impact overpowers their tone.28 This eccentric force would theoretically create muscle fiber tearing and damage to surrounding vasculature, lymphatics, and even neural tissues.2,28 The brunt of the remaining force may then be taken up by passive structures such as the anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL).28 Following this acceleration phase, the head flexes as the torso decelerates. Flexion of the head may be potentiated by contraction of the neck flexors stimulated by the stretch reflex from the preceding acceleration phase.28 This combination may excessively load the posterior cervical structures. Studies in animal models29 have implicated that, during this deceleration phase, the upper cervical spine, serving as a pivot point, sustains the greatest injury as supportive structures serve to decelerate the head. By this mechanism the ligamentous structures such as the alar and transverse ligaments as well as the tectorial membrane, suboccipital, and upper cervical muscles may be traumatized.21,30–33 Other authors have reported that acceleration and deceleration force may also be associated with a significant amount of cervical axial loading and distraction.22,34 These forces may create irritation of more central nervous structures such as the spinal cord, brainstem, and nerve roots.35 This direct impact on neural structures, as well as the supportive musculoligamentous structures have been implicated in the development of acute pain and also the perpetuation of chronic pain following cervical whiplash, including the presence of adverse neural tension (Fig. 55.1) and central sensitization.35,36

MUSCULOLIGAMENTOUS INJURY

Clinical experience

Janes and Hooshmand2 in 1965 was one of the first to clinically report on the etiology of soft tissue pain following cervical flexion–extension injuries. They referred to these injuries as cervical sprains and inferred that in a rear-end collision, the patient is in a relaxed position, deprived of the protection usually achieved by contraction of the cervical paraspinal musculature. In Janes’s experience, these ‘sprains’ were caused by injury to the cervical ligaments such as the interspinous ligaments, ligamentum nuchae, and ALL. They provided evidence for this statement by reporting on the surgical findings of 32 patients with cervical pain following cervical trauma. Twenty-three had experienced whiplash injuries. Upon surgical exploration, eight of these patients had definite rupture of the interspinous ligament at C6 or C7 with scar formation, while 13 had hypermobility of one or two spinous processes of the cervical vertebrae. Additionally, the ligamentum nuchae and interspinous ligaments had developed calcifications indicative of degenerative changes and scarring. Approximately 90% of patients in this case series had good to excellent outcomes with 1–7 year follow-up after posterior cervical fixation. Unfortunately, Janes and Hooshmand did not report on disc or zygapophyseal injuries in this case series but this report provided clear evidence that ligamentous damage may serve as a potential pain generator following a cervical whiplash.

Hohl8,21 and later Hirsch et al.22 reported on clinical findings associated with soft tissue injury following whiplash based upon clinical observations. They concluded that acute cervical pain following whiplash was partly from soft tissue injury, namely musculoligamentous damage, but provided no new substantial clinical proof to support this theory. Like most, they postulated that rear-end collisions resulted in the most disability and that injury to the anterior or posterior musculature occurred during cervical acceleration and deceleration33,37 Front-end collisions, creating forward cervical flexion, it was felt, would result in injury mainly to the posterior musculature and ligaments.8,21,22 Interestingly, these authors were among the first to report that patients often had pain radiating into the upper limb that did not follow a radicular pattern and suggested that these unexplainable symptoms may be due to irritation of injured musculoligamentous structures. It is known that stimulation of these supportive structures with hypertonic saline produces somatic pain patterns.38–41 More recent clinical observations suggest that these nonradicular referral patterns may also be attributable to central neural irritation, as evidenced by adverse neural tension.36

Animal studies

Despite these case series and clinical experiences, the majority of evidence suggesting damage to the musculoligamentous structures following cervical whiplash is found predominantly from animal studies. Macnab,19 utilizing a monkey model, simulated significant acceleration injuries to the cervical spine. His studies produced cervical muscular injuries that ranged from minor tears in the sternocleidomastoid to tears of the longus colli muscle and hemorrhage within the esophagus. In addition, damage to the longus colli resulted in associated retropharyngeal hemorrhage and damage to the cervical sympathetic nervous system. These findings may explain the clinical complaints of dysphagia, dizziness, and vertigo in patients following whiplash. These acceleration injuries also resulted in avulsion of the anterior longitudinal ligament and separation of the disc from the cervical vertebrae28 but these injuries never occurred without concomitant injury to the anterior cervical musculature. Although Macnab admitted that less severe injuries would not result in such significant soft tissue trauma, he was among the first to provide pathological evidence that the cervical muscle and ligaments could contribute to pain and cervical dysfunction following a whiplash injury.

Wickstrom et al.,42 also utilizing a primate model, produced acceleration and deceleration injuries to the cervical spine. With this more accurate simulation of the whiplash injury, there was a high proportion of damage to the posterior ligamentous complex and cervical nerve roots. Inflammation and hemorrhage within the trapezius and splenius capitis muscles was detected in approximately 25% of the specimens. Additionally, Wickstrom et al.43 confirmed Macnab’s findings, demonstrating that the ALL may indeed be damaged during the acceleration phase of whiplash, separating from the anterior cervical disc and vertebral body. Understandably, these injuries were not identified by utilizing plain radiographs, suggesting that patients, even with significant soft tissue injury, will have negative radiographic examination.

Unterharnscheidt29 was among the first to separate what damage would be created by the acceleration phase versus the deceleration phase of the whiplash. He remarked that the deceleration phase of whiplash produced hemorrhage and tearing to the origin of cervical musculature as well as damage to the posterior longitudinal ligament, tectorial membrane, transverse, and alar ligaments. Ironically, he failed to reveal any major alterations in the ligamentous structures during the acceleration phase but did confirm the presence of bleeding within the sternocleidomastoid. Liu et al.,44 as well as Bocci and Orso,30 have shown in experimental animal models that during the acceleration phase of whiplash, the cervical ALL, alar ligament, transverse ligament, and even PLL may be injured. This is noteworthy, as previous authors have implicated the role of deceleration as the cause of injury to these posterior structures.

Cadaveric studies

Clinical evidence in humans confirming soft tissue injury after whiplash is relatively sparse and often relies on cadaveric or postmortem specimens to identify musculoligamentous injuries. However, it has been refuted that cadaveric specimens, although more anatomically accurate than an animal model, cannot adequately replicate normal living tissue since it lacks contractile muscle that may be protective during whiplash. Postmortem analysis has also been cited as not being representative of the typical whiplash mechanism since the majority of victims who die have sustained forces beyond what is considered typical for low to moderate velocity car collisions. Despite these arguments, Clemens and Burow45 subjected unembalmed cadavers to rear-end impacts with approximate average velocities of 19 km/h. Significant ligamentous injuries were observed with the majority of the injuries occurring about the C5–6 or C6–7 level. Injury to the ALL was found in 80%, while 10% of the cadavers had injury to the PLL, and 10% had injury to the ligamentum flavum. Dural attachments to these ligaments may generate tensile forces on nearby neural structures.46,47 These cadaveric studies lend credence to the belief that ligamentous injuries, in addition to muscular injury, are partly responsible for local and radicular pain following whiplash.46,47

Electromyographic evidence

Although it was initially reported that the cervical muscles do not participate in protection during cervical whiplash,48 there has been subsequent electromyographic evidence to support the theory that the cervical musculature undergoes tremendous activation during a whiplash injury.49 This activation, particularly if occurring eccentrically, would potentially explain damage to supportive muscular structures. Additionally, it has been recognized that anticipatory contraction of supportive musculature prior to the collision may be protective since there is a reduction of head acceleration and angular displacement.50,51

Magnusson et al.52 were among the first to measure electromyographic activity from muscles during a simulated whiplash injury. Recordings from the SCM, trapezius, semispinalis capitis, splenius capitis, and levator scapulae revealed significant activity from all muscles. The first muscles to be activated were from the superficial muscles including the trapezius, levator scapulae, and SCM, while the deeper muscles, semispinalis capitis and splenius capitis, contracted later and for longer periods. The authors theorized that the larger superficial muscles with longer moment arms grossly stabilized the spine while the deeper muscles continued with sustained contractions to provide segmental control to the cervical spine during the acceleration and deceleration phases of whiplash.

Kumar et al.49 confirmed these results, recording EMG activity from anterior and posterior musculature during rear-end impact of various velocities. Muscle responses were greater with higher levels of acceleration. The SCM generated up to 179% of its maximal voluntary contraction but awareness of impending impact significantly reduced the muscle response, whereas a lack of awareness had the opposite effect. This study confirmed that significant force is absorbed by the cervical supportive musculature and that knowledge of an impending collision may help reduce the injury to musculature incurred at the time of impact.

Siegmund et al.,53 however, have stated that most laboratory EMG testing falsely represents what occurs during automobile collisions since participants in experiments are aware that at some point a collision will take place and may contract supportive musculature in anticipation. Therefore, to more accurately measure electromyographic data from muscles during whiplash, the following experiment was performed. Three subgroups of participants were subjected to a whiplash perturbation while having EMG activity recorded from their paraspinals and SCMs. The first group was completely aware that a collision was to occur, the second group knew that a collision was to occur but was unsure when, and the third group, as evidenced by resting baseline electromyographic activity, was completely surprised when the collision took place. Siegmund et al. showed that the SCM and paraspinals in male subjects of the surprised group had a delay in onset of activation 7 ms and 5 ms, respectively, compared to the alerted participants. Cervical paraspinal amplitudes were also 260% higher in surprised male subjects and their flexion acceleration velocities were significantly greater. Although the purpose of this paper was to more accurately assess mechanics closer to a real-life situation, the kinematics and electromyographic data of these studies reveal the significant trauma that the cervical soft tissues may sustain during a whiplash injury.

Radiologic studies

There have been few published articles demonstrating the importance of radiologic studies in understanding the mechanism and presence of cervical musculoligamentous lesions after a whiplash injury. Although there has been diagnostic ultrasound evidence of soft tissue injury following whiplash,54 Davis et al.55 reported on the soft tissue abnormalities utilizing MRI in nine whiplash patients. Three patients had injuries to the ligamentous structures, including two to the ALL and one to the interspinous ligament, a recognized pain generator. These injuries are compatible with the animal studies and cadaveric studies cited above.

Utilizing CT scan imaging techniques, Dvorak and associates56 have indicated the importance of the alar ligaments in providing higher cervical level stability during whiplash. It was postulated that these ligaments may be irreversibly stretched or ruptured while the head is rotated and flexed during high-speed trauma, especially in a rear-end collision or unexpected impact. Although further studies are needed to confirm this potentially injurious mechanism, White and Panjabi34 have suggested that insufficient alar ligament support may lead to irritation of the spinal cord and brainstem elements, potentially contributing to pain and disability produced by soft tissue injuries. Many investigators are now realizing that this potential for central nervous system sensitization may, in addition to soft tissue injury, contribute to both acute and chronic pain following cervical acceleration, deceleration, axial compression, and distraction that occurs during whiplash injury (Table 55.1).34,36

Table 55.1 Summary of Soft Tissues Injured During the Phases of Whiplash Injury Based upon Animal, Cadaveric, Electromyographic, and Radiologic Studies

| Acceleration Phase | Deceleration Phase |

|---|---|

| Esophagus | Trapezius |

| Sternocleidomastoid | Splenius capitis |

| Longus colli | Semispinalis capitis |

| Anterior longitudinal ligament | Levator scapula |

| Alar ligament | Posterior longitudinal ligament |

| Transverse ligament | Alar ligament |

| Posterior longitudinal ligament | Transverse ligament |

| Cervical sympathetics | Tectorial membrane |

| Cervical nerve roots | Interspinous ligament |

| Spinal cord/brainstem elements | |

| Cervical nerve roots |

CHRONIC PAIN FROM WAD WITH IMPLICATIONS FROM CENTRAL NEURAL MECHANISMS

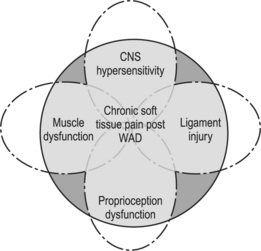

Although the majority of individuals improve over time, chronic pain following whiplash does indeed exist. Patients with chronic WAD, much like that occurring from acute whiplash, probably experience pain from many etiologies. The cervical disc, zygapophyseal joint, and soft tissue structures have all been implicated as potential pain generators and the complex interaction of these tissues may contribute to the perpetuation of chronic cases.11,12,57,58 However, many patients continue to experience persisting symptoms despite the absence of abnormalities on diagnostic tests, relief from therapeutic spine and soft tissue injections, and even cervical spine surgery. Many of these patients are labeled as myofascial pain patients, having a cadre of bizarre symptoms including sleep and psychological disturbances as well as nonradicular referred pain into the limbs and head.15 Although the exact etiology of chronic WAD remains elusive and a complete discussion of all the various causes is beyond the scope of this chapter, there are some recent theories to suggest that some patients may be experiencing a combination of cervical muscle and joint dysfunction as well as central neural hypersensitivity.15,36 Hopefully, an understanding of these potential pain mechanisms may help clinicians provide a more comprehensive treatment strategy for chronic WAD patients.

Although persistent ligamentous damage may exist,2 some have found evidence of persistent dysfunction, reduced blood flow, and concomitant pain within the cervical musculature following whiplash injury. For example, Larsson et al.,59 using laser Doppler flowmetry, demonstrated that patients who had chronic neck pain following a car collision had impaired regulation of the microcirculation in painful trapezius muscles. During static contractions, the trapezius of these patients had a decreased microcirculatory flow compared to control subjects who actually demonstrated an increase in flow during activity. This relative reduction in flow may perpetuate muscular dysfunction secondary to the accumulation of metabolites, stimulation of afferents and associated gamma motor neurons, and reflex-mediated stiffness. However, Larsson et al. did not see an increase in neural excitability, but rather saw a reduction in EMG activity possibly related to pain inhibition or fatigue. Cervical muscular dysfunction has also been identified in patients with chronic WAD. In a study by Nederhand et al.,60 patients with chronic WAD type II were monitored with surface EMG during static postures, unilateral dynamic manual exercise, and upon relaxation after the exercises. Compared to control subjects, the whiplash patients had a decreased ability to relax the trapezius following activity. From this study, Nederhand at al. proposed that patients with WAD may acquire fear of movement and physical activity, which leads to guarding and a decrease ability to relax associated cervical musculature.61 Theoretically, this continued muscular contraction, reduction of blood flow, and perpetuation of muscle dysfunction, and fear-related avoidance lead to the vicious cycle of chronic pain following WAD. Therefore, an underlying disturbance in both the microcirculation with exercise and the inability for muscles to relax postexercise may contribute to the perpetuation of pain.

Finally, there has been relative recent evidence to suggest the presence of abnormal central nervous system processing and central neural hypersensitivity following the whiplash injury.62,63 For example, Koelbaek et al.64 using pain pressure thresholds and VAS scores following infusion of saline both into painful and nonpainful tissues, reported that patients with chronic pain following whiplash had lower pressure pain thresholds and larger areas of pain with higher VAS scores compared to control subjects. These higher VAS scores and wider areas of pain following the saline infusion were present both in painful paracervical musculature as well as in nonpainful control muscles not involved in the whiplash such as the tibialis anterior. Similarly, Sterling et al.36 have found that these patients have heightened sensitivity to sensory stimuli such as heat and cold as well as increased mechanosensitivity of peripheral nerves to adverse neural tension, and deficits in proprioception of the head and cervical spine soon after injury. Difficulty with proprioception and hypersensitivity to sensory stimuli may help explain the perpetuation of symptoms not only from overlying muscle but deeper structures such as the cervical zygapophyseal joint and disc. Hypersensitivity of the nervous system and adverse neural tension, together with sclerotomal pain patterns referred from deeper structures, may also explain the myriad of nonradicular referral pain patterns seen in these perplexing patients.

SUMMARY

In conclusion, cervical pain and upper limb symptoms following whiplash are usually due to cervical disc, zygapophyseal, and soft tissue injury. In the majority of cases, injury to soft tissue structures such as the supportive muscles and ligaments as evidenced by animal, cadaveric, and electromyographic studies occur due to the acceleration and deceleration. Fortunately, the majority of these injuries heal with time. Some patients, however, have continued symptoms and are often labeled as having myofascial pain. However, the clinician should also suspect persistent ligamentous injury, concomitant muscle and joint dysfunction, and possibly underlying central hypersensitivity as the cause of chronic WAD (Fig. 55.2).

1 Spitzer WO, Skovron ML, Salmi LR, et al. Scientific monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders: redefining ‘whiplash’ and its management. Spine. 1995;20(8 Suppl):1S-73S.

2 Janes JM, Hooshmand H. Severe extension-flexion injuries of the cervical spine. Mayo Clinic Proc. 1965;40:353-369.

3 Ratliff AH. Whiplash injuries.[comment]. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1997;79(4):517-519.

4 Radanov BP, Sturzenegger M. Predicting recovery from common whiplash. Eur Neurol. 1996;36(1):48-51.

5 Radanov BP, Sturzenegger M, De Stefano G, et al. Relationship between early somatic, radiological, cognitive and psychosocial findings and outcome during a one-year follow-up in 117 patients suffering from common whiplash. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33(5):442-448.

6 Radanov BP, Sturzenegger M, Di Stefano G. Long-term outcome after whiplash injury. A 2-year follow-up considering features of injury mechanism and somatic, radiologic, and psychosocial findings. Medicine. 1995;74(5):281-297.

7 Gargan MF, Bannister GC. Long-term prognosis of soft-tissue injuries of the neck. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1990;72(5):901-903.

8 Hohl M. Soft-tissue injuries of the neck in automobile accidents. Factors influencing prognosis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1974;56(8):1675-1682.

9 Parmer H, Raymalcers R. Neck injuries from rear-impact road traffic accidents: prognosis in persons seeking compensation. Injury. 1993;24:75-78.

10 Lord SM, Barnsley L, Wallis BJ, et al. Chronic cervical zygapophyseal joint pain after whiplash. A placebo-controlled prevalence study. Spine. 1996;21(15):1737-1744. discussion 1744–1745

11 Barnsley L, Lord SM, Bogduk N. Clinical review: whiplash injury. Pain. 1994;58:283-307.

12 Slipman C, Chow D. Cervical disc pain and radiculopathy after whiplash. In: Malanga GA, Nadler S, editors. Whiplash. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus; 2002:161-180.

13 Taylor JR, Finch P. Acute injury of the neck: anatomical and pathological basis of pain. Ann Acad Med, Singapore. 1993;22(2):187-192.

14 Taylor JR, Twomey LT. Acute injuries to cervical joints. An autopsy study of neck sprain. Spine. 1993;18(9):1115-1122.

15 Nadler S. Myofascial pain after whiplash injury. In: Malanga GA, Nadler S, editors. Whiplash. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus; 2002:219-240.

16 Maimaris C, Barnes MR, Allen MJ. ‘Whiplash injuries’ of the neck: a retrospective study. Injury. 1988;19(6):393-396.

17 Bring G, Westman G. Chronic posttraumatic syndrome after whiplash injury. A pilot study of 22 patients. Scand J Primary Health Care. 1991;9(2):135-141.

18 Macnab I. The ‘whiplash syndrome.’. Orthoped Clin N Am. 1971;2(2):389-403.

19 Macnab I. Acceleration injuries of the cervical spine. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1964;46:1797-1799.

20 Fricton J. Myofascial pain and whiplash. Spine State of the Art Reviews. 1993;7(3):403-422.

21 Hohl M. Soft tissue injuries of the neck. Clin Orthopaed Related Res. 1975;109:42-49.

22 Hirsch SA, Hirsch PJ, Hiramoto H, et al. Whiplash syndrome. Fact or fiction? Orthoped Clin N Am. 1988;19(4):791-795.

23 Kanoeka K, Ono L, Inami S, et al. Abnormal segmental motion of the cervical spine during whiplash loading. J Jap Orthop Assoc. 1997;71:S16S-SS80.

24 Grauer JN, Panjabi MM, Cholewicki J, et al. Whiplash produces an S-shaped curvature of the neck with hyperextension at lower levels. Spine. 1997;22(21):2489-2494.

25 McConnell W, Howard R, Guzman H. Analysis of human test subjects kinematic responses to low-velocity rear-end impacts. In: Proceedings of the 37th STAPP car crash conference. San Antonio, Texas; 1993:21–30.

26 Yoganandan N, Pintar F. Facet joint local component kinetics in whiplash trauma. ASME. 1997;36:221-222.

27 Matsushita T, Sato T, Hirabayashi K, et al. X-ray study of the human neck motion due to head inertia loading. In: Proceedings of of the 38th STAPP car crash conference. Fort Lauderdale, Fl; 1994:55–64.

28 Croft A. Soft tissue injury: Long and short-term effects. In: Foreman S, Croft A, editors. Whiplash injuries: The cervical acceleration/deceleration syndrome. 2nd edn. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1995:289-362.

29 Unterharnscheidt F. Pathological and neuropathological findings in rhesus monkeys subjected to −Gx and +Gx indirect impact acceleration. In: Sances A, Thomas D, Ewinf C, et al, editors. Mechanisms of head and spine trauma. Goshen: Aloray; 1986:565-663.

30 Bocchi L, Orso C. Whiplash injuries of the cervical spine. South Ital J Ortho Traumatol. 1983;Suppl:171-181.

31 Wickstrom J, LaRocca H. Head and neck injuries from acceleration–deceleration forces. In: Ruge D, Wiltse LL, editors. Spinal disorders: diagnosis and treatment. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1977:350.

32 Gotten N. Survey of one hundred cases of whiplash injury after settlement of litigation. J Am Med Assoc. 1956;162(9):865-867.

33 Whitley JE, Forsyth HF. The classification of cervical spine injuries. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nuclear Med. 1960;83:633-644.

34 White A, Panjabi M. Practical biomechanics of spine trauma. In: White A, Panjabi M, editors. Clinical biomechanics of the spine. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins; 1990:169-276.

35 Butler D. Neurodynamics. In: Butler D, editor. The sensitive nervous system. Australia: Noigroup Publications; 2000:96-126.

36 Sterling M, Treleaven J, Jull G. Responses to a clinical test of mechanical provocation of nerve tissue in whiplash associated disorder [see comment]. Manual Ther. 2002;7(2):89-94.

37 Bailey RW, Badgley CE. Stabilization of the cervical spine by anterior fusion. Am J Orthoped. 1960;42-A:565-594.

38 Kellegren J. Observations on referred pain arising from muscle. Clin Sci. 1938;3:175-190.

39 Kellegren J. On the distribution of pain arising from deep somatic structures with charts of segmental pain. Clin Sci. 1939;3:35-46.

40 Feinstein B, Langton JN, Jameson RM, et al. Experiments on pain referred from deep somatic tissues. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1954;36-A(5):981-997.

41 Inman V, Saunders J. Referred pain from skeletal structures. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1944;99:660.

42 Wickstrom J, Martinez JE, Rodriguez R. Cervical sprain syndrome: Experimental acceleration injuries of the head and neck. In: Proceedings prevention of highway injury. Ann Arbor, MI: Highway Safety Institute, Univ of Michigan; 1967:182-187.

43 Wickstrom J, Martinez J, Rodriguez R. Frankel V, editor. Cervical pain. New York: Pergammon Press, 1972.

44 Liu Y, Wickstrom J, Saltzberg B, et al. Subcortical EEG changes in rhesus monkeys following experimental whiplash. ACEMB, 1973;404.

45 Clemens H, Burrow K. Experimental investigation on injury mechanism of cervical spine at frontal and rear-end vehicle impacts. In: 16th STAPP car crash conference. NY; 1972:76.

46 Spencer DL. The anatomical basis of sciatica secondary to herniated lumbar disc: a review [Review] [41 refs]. Neurol Res. 1999;21:S33-S36.

47 Spencer DL, Irwin GS, Miller JA. Anatomy and significance of fixation of the lumbosacral nerve roots in sciatica. Spine. 1983;6:672-679.

48 Tennyson SA, Mital NK, King AI. Electromyographic signals of the spinal musculature during +Gz impact acceleration. Orthope Clin N Am. 1977;8(1):97-119.

49 Kumar S, Narayan Y, Amell T. An electromyographic study of low-velocity rear-end impacts. Spine. 2002;27(10):1044-1055.

50 Ono K, Kanoeka K, Wittek A. Cervical injury mechanism based on the analysis of human cervical vertebral motion and head–neck torso kinematics during low-speed rear impact. In: Proceedings of the 41st STAPP car crash. Warrendale, PA; 1997:339–356.

51 Pope M, Aleksiev A, Hasselquist L. Neurophysiologic mechanisms of low-velocity non-head contact cervical accelration. In: Gunzberg R, Szpalski M, editors. Whiplash injuries: Current concepts in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the cervical whiplash syndrome. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1999:89-93.

52 Magnusson ML, Pope MH, Hasselquist L, et al. Cervical electromyographic activity during low-speed rear impact. Eur Spine J. 1999;8:118-125.

53 Siegmund GP, Sanderson DJ, Myers BS, et al. Awareness affects the response of human subjects exposed to a single whiplash-like perturbation. Spine. 2003;28(7):671-679.

54 Martino F, Ettorre GC, Cafaro E, et al. [Muscle-tendon echography in acute cervical sprain traumas. Preliminary results]. Radiologia Medica. 1992;83(3):211-215.

55 Davis SJ, Teresi LM, Bradley WGJr, et al. Cervical spine hyperextension injuries: MR findings. Radiology. 1991;180(1):245-251.

56 Dvorak J, Hayek J, Zehnder R. CT-functional diagnostics of the rotatory instability of the upper cervical spine. Part 2. An evaluation on healthy adults and patients with suspected instability. Spine. 1987;12(8):726-731.

57 Lord SM, Barnsley L, Wallis BJ, et al. Chronic cervical zygapophyseal joint pain after whiplash. A placebo-controlled prevalence study [see comment]. Spine. 1996;21(15):1737-1744. discussion 1744–1745

58 Chow D, Slipman C. Whiplash-associated cervical facet joint syndrome. In: Malanga GA, Nadler S, editors. Whiplash. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus; 2002:150-160.

59 Larsson SE, Alund M, Cai H, et al. Chronic pain after soft-tissue injury of the cervical spine: trapezius muscle blood flow and electromyography at static loads and fatigue. Pain. 1994;57(2):173-180.

60 Nederhand MJ, Hermens HJ, Baten CT, et al. Cervical muscle dysfunction in the chronic whiplash associated disorder grade II (WAD-II). Spine. 2000;25(15):1938-1943.

61 Nederhand MJ, Hermens HJ, Turk DC, et al. Cervical muscle dysfunction in chronic whiplash-associated disorder grade 2: the relevance of the trauma. Spine. 2002;27(10):1056-1061.

62 Sterling M, Jull G, Vicenzino B, et al. Characterization of acute whiplash-associated disorders. Spine. 2004;29(2):182-188.

63 Sterling M, Jull G, Vicenzino B, et al. Sensory hypersensitivity occurs soon after whiplash injury and is associated with poor recovery. Pain. 2003;104(3):509-517.

64 Koelbaek Johansen M, Graven-Nielsen T, Schou Olesen A, et al. Generalised muscular hyperalgesia in chronic whiplash syndrome [see comment]. Pain. 1999;83(2):229-234.