164 Sodium and Water Balance

• Most signs and symptoms of clinically significant hyponatremia are related to an increase in cellular volume in the central nervous system and subsequent cerebral edema.

• Hyposmolar hypovolemic hyponatremia, the most common type of hyponatremia encountered in the emergency department, is seen in patients with severe total body water depletion in excess of sodium loss.

• Diagnostic criteria for the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) include hyposmolar hyponatremia, inappropriately concentrated urine, and exclusion of other causes of hyposmolar euvolemic hyponatremia such as hypothyroidism and adrenal insufficiency.

• Hypovolemic hypernatremia, the most common cause seen in the emergency department, results from severe total body water depletion.

• Patients with central diabetes insipidus produce dilute urine because of a decrease in ADH secretion from the hypothalamus; those with nephrogenic DI exhibit a decreased response to ADH at the renal tubule.

• Osmotic demyelination syndrome, the most serious complication of the treatment of hyponatremia, occurs when the administration of relatively hyperosmolar intravenous fluid causes intracellular water to rapidly diffuse out of central nervous system cells.

• The most serious complication of therapy for hypernatremia is the development of cerebral edema secondary to excessively rapid rehydration.

Scope

Hyponatremia is diagnosed when the serum sodium level is lower than 135 mEq/L, but clinical signs and symptoms most often occur when sodium falls below 130. Hyponatremia most commonly occurs in the very young and the very old, with prevalence increasing with advancing age. Hyponatremia is observed in infants given tap water as a home remedy for gastroenteritis and in elderly patients with a poorly regulated thirst mechanism or an inability to procure fluids because of immobility (or both).1,2

Hypernatremia, a plasma sodium level higher than 145 mEq/L, most commonly results from inadequate water intake. In the very young, this situation usually occurs secondary to water loss exceeding intake, such as with diarrheal illness; in the geriatric population, hypernatremia may result from a poor sense of thirst or an inability to obtain adequate fluids because of physical or mental impairment. Hypernatremia is less common than hyponatremia, but it is associated with a far greater mortality rate of approximately 50%, primarily from the causative disease states in elderly patients and from the direct neurologic effects of the high sodium concentration in the very young.3

Pathophysiology

Hyponatremia

The low osmolality of the intravascular space and the relatively high osmolality of the intracellular space results in an osmotic gradient and diffusion of water into the cell. The resulting cellular edema is generally well tolerated by most tissues, except when it occurs in a confined space such as the central nervous system (CNS). The initial, rapid response to the increase in CNS cellular volume is diffusion of electrolytes and water out of the cell, which leads to a partial reduction in glial cell volume. Continuing hyponatremia over the next 48 to 72 hours generates slow diffusion of organic osmolytes, primarily large amino acids, out of the cell, thereby further reducing cell volume.4 Treatment of hyponatremia with intravenous fluid (IVF) may then lead to a state of relative hyperosmolality in the extracellular space with resultant diffusion of water out of the cell and continued reduction in cellular volume. This cycle creates the most serious treatment complication of hyponatremia: osmotic demyelination syndrome (otherwise known as central pontine myelinolysis).5

Hypernatremia

In hypernatremia, water diffuses out of the cell along the osmotic gradient, which results in loss of cellular volume. In the acute phase, electrolytes and water rapidly diffuse into the cell to partially restore cellular volume. With ongoing hypernatremia, slow redistribution of osmolytes occurs and water diffuses into the cell. With treatment, the relatively hyposmolar IVF leads to an osmotic gradient that promotes further diffusion of water into the cell. The size of the larger organic osmolytes prevents rapid diffusion out of the cell and results in the most serious treatment complication of hypernatremia: cerebral edema.6,7

Clinical Presentation

Hyponatremia

Symptoms of hyponatremia include nausea, headache, and general malaise with sodium levels of 125 to 130 and lethargy, confusion, agitation, psychosis, and seizures as the sodium level falls to the range of 115 to 120; severe symptoms develop at 110 regardless of the rate of change. Severe CNS signs observed with hyponatremia include a decreased level of alertness, focal or generalized seizure activity, and signs of brainstem herniation such as unilateral dilated pupil, posturing, and respiratory arrest.8

Hypernatremia

The signs and symptoms of hypernatremia depend on age. Infants exhibit restlessness, tachypnea, characteristic high-pitched crying, alternating irritability and lethargy, and hypotonia. Elderly patients have nausea, weakness, altered mental status, agitation, irritability, lethargy, stupor, coma, and seizures. The severity of the CNS symptoms correlates with serum sodium levels.9

Differential Diagnosis and Classifications

Hyponatremia

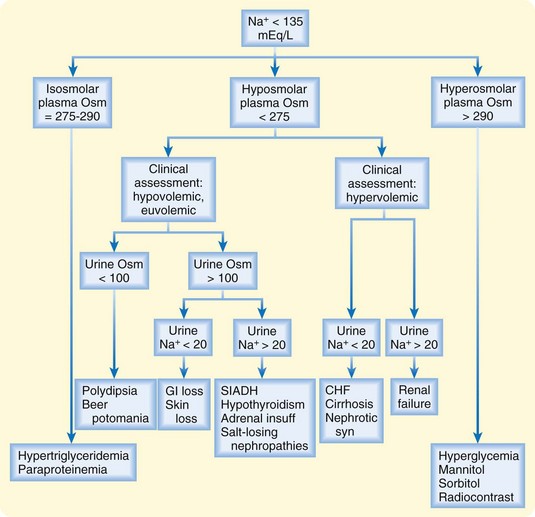

The differential diagnosis of hyponatremia begins with determination of serum osmolality (Fig. 164.1).4 Osmolality is measured by osmometry in the laboratory or is calculated according to the following formula:

Fig. 164.1 Diagnostic algorithm for hyponatremia.

(Adapted from Kumar S, Berl T. Sodium. Lancet 1998;352:220-8.)

Hyposmolar hypovolemic hyponatremia, the most common type of hyponatremia encountered in the ED, is seen in patients with severe depletion of total body water (TBW) in excess of sodium loss.10 Urine osmolality and sodium determinations allow further narrowing of the differential diagnosis. Dilute urine (urine osmolality > 100 mOsm/kg) suggests polydipsia or beer potomania. In patients with urine osmolality greater than 100 mOsm/kg, urinary sodium levels lower than 20 mEq/L indicate an extrarenal source of the sodium and water loss. Extrarenal causes of hyponatremia include gastrointestinal problems such as vomiting or diarrhea and skin loss from severe burns. Urinary sodium levels higher than 20 mEq/L suggest a renal source of the sodium and water loss, such as sodium-losing nephropathy, hypoaldosteronism, diuretic excess, or osmotic diuresis.

Hyposmolar euvolemic hyponatremia is most commonly associated with the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) (Box 164.1). ADH, or vasopressin, decreases free water excretion and results in inappropriately concentrated urine (urine osmolality >100 mOsm/kg) and a urine sodium concentration higher than 20 mEq/L. SIADH may result from various malignancies, pulmonary disorders, CNS diseases, and several drugs.11–13 Diagnostic criteria for SIADH include hyposmolar hyponatremia, inappropriately concentrated urine, and exclusion other causes of hyposmolar euvolemic hyponatremia such as hypothyroidism and adrenal insufficiency.

Hypernatremia

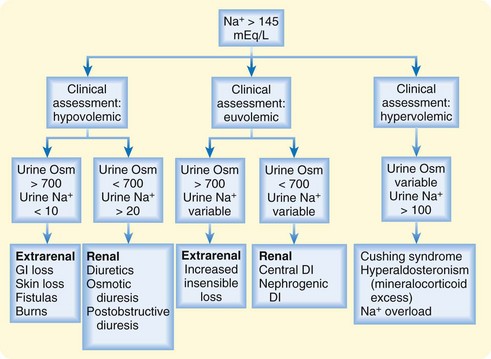

Figure 164.2 is an algorithm for the diagnosis of hypernatremia.4 Hypernatremia may also be classified as hypovolemic, euvolemic, or hypervolemic.

Fig. 164.2 Diagnostic algorithm for hypernatremia.

DI, Diabetes insipidus; GI, gastrointestinal; Osm, osmolality.

(Adapted from Kumar S, Berl T. Sodium. Lancet 1998;352:220-8.)

Hypovolemic hypernatremia, the most common cause seen in the ED, results from severe depletion of TBW. Urine sodium measurement allows determination of an extrarenal or renal source of the water loss. Levels lower than 10 mEq/L suggest an extrarenal source of the water loss, such as the skin (excessive sweating or severe burns) or the gastrointestinal system (vomiting or diarrhea). Levels higher than 20 mEq/L suggest renal causes such as excessive diuretic use, osmotic diuresis, postobstructive diuresis, or intrinsic renal disease.6

Euvolemic hypernatremia results from water loss without solute loss, with the majority of water loss most notably being from the intracellular space. Water loss occurs from both extrarenal and renal sources. Extrarenal sources include insensible skin and respiratory loss, coupled with lack of water intake because of impaired thirst mechanisms or inability to procure fluids. Urine osmolality is typically high (>700 mOsm/kg) as a result of secretion of ADH. Urine sodium levels vary. Renal water loss occurs secondary to diabetes insipidus (DI) of central or nephrogenic origin and results in dilute urine (urine osmolality < 700 mOsm/kg). Patients with central DI produce dilute urine because of a decrease in ADH secretion from the hypothalamus; those with nephrogenic DI exhibit a decreased response to ADH at the renal tubule.6

Treatment

Hyponatremia

Osmotic demyelination syndrome (ODS), the most serious complication of the treatment of hyponatremia, occurs when the administration of relatively hyperosmolar IVF causes intracellular water to rapidly diffuse out of CNS cells. Patients typically improve transiently after IVF administration, only to deteriorate a week after treatment. Signs and symptoms include altered mental status, dysarthria, vertigo, parkinsonism, pseudobulbar palsy, diffuse spastic hypertonia, quadriparesis, and coma. To minimize the risk for ODS, the absolute change in serum sodium over a 48-hour period must not exceed 15 to 20 mEq/L. Additional risk factors for the development of ODS include alcoholism, malnutrition, and liver transplantation.5

In patients with severe neurologic symptoms (seizures, coma, or respiratory arrest) and laboratory-confirmed hyposmolar hypovolemic hyponatremia, the likelihood of cerebral edema outweighs the potential risk for treatment-related ODS secondary to rapid correction of the hyponatremic state. In this clinical situation, administration of hypertonic saline (HTS, 3%) is suggested for the first 2 to 4 hours or less if the patient’s condition improves with a maximum rate of sodium correction of 1.0 to 2.0 mEq/L/hr. Seizure risk usually declines with a serum sodium correction of approximately 5 mEq/L. Patients with acute hyponatremia for less than 48 hours may tolerate more rapid correction of the sodium concentration. Hyponatremic patients with less severe symptoms usually have a more chronic condition. The risk for ODS outweighs the benefits of rapid correction in this group, and the recommended rate of sodium correction is less than 0.5 mEq/L/hr.8,14

TBW in liters equals the patient’s mass in kilograms multiplied by a constant that depends on the patient’s gender and age (young men, 0.6; young women and elderly men, 0.5; elderly women, 0.4).15 See the “Facts and Formulas” box to determine the sodium content of 1 L of commonly used IVF.

![]() Facts and Formulas

Facts and Formulas

Sodium Content of Commonly Used Intravenous Fluids

| Intravenous Fluid | Na+ (mEq/L) |

|---|---|

| D5W | 0 |

| 0.45% Saline | 77 |

| 0.9% Saline | 154 |

| 3% Saline | 513 |

D5W, 5% Dextrose in water.

Some authors do not endorse the use of formulas to guide the treatment of hyposmolar hyponatremic patients with seizures. Instead, they recommend an empiric IV bolus of 100 mL of 3% HTS, followed by up to two repeated doses if the seizures have not resolved, with the goal of increasing serum sodium 5 to 6 mEq/L in the first 1 to 2 hours of treatment. Monitoring of serum sodium after the second IV bolus and every 2 hours during HTS therapy is required to guide further therapy. HTS is discontinued once serum sodium levels have increased by 10 mEq/L in the first 5 hours or if the symptoms resolve. Further recommendations include avoidance of both overcorrection and an absolute increase exceeding 15 to 20 mEq/L in the first 48 hours of treatment.16

Hypernatremia

Another correction method is to calculate the effect of 1 L of a given IVF on the patient’s sodium level by using the following formula and values described by Androgué and Madias (Box 164.2)7:

Box 164.2

High-Risk Neurologic Complications Occurring in Hyponatremic Patients

Adapted from Lauriat SM, Berl T. The hyponatremic patient: practical focus on therapy. J Am Soc Nephrol 1997;8:1599-607.

The most serious complication of therapy for hypernatremia is the development of cerebral edema secondary to excessively rapid rehydration (see Box 164.2). In the chronic hypernatremic state, large organic osmolytes that slowly accumulated in CNS cells during the adaptive phase are unable to rapidly diffuse into the extracellular space when a relatively hypotonic fluid is administered.

1 Gankam Kengne F, Andres C, Sattar L, et al. Mild hyponatremia and risk of fracture in the ambulatory elderly. QJM. 2008;101:583–588.

2 Decaux G. Is asymptomatic hyponatremia really asymptomatic? Am J Med. 2006;119(7A):S79–S82.

3 Mandal AK, Saklayen MG, Hillman NM, et al. Predictive factors for high mortality in hypernatremic patients. Am J Emerg Med. 1997;15:130–132.

4 Kumar S, Berl T. Sodium. Lancet. 1998;352:220–228.

5 King JD, Rosner MH. Osmotic demyelination syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 2010;339:561–567.

6 Palevsky PM. Hypernatremia. Semin Nephrol. 1998;18:20–30.

7 Adrogué HJ, Madias NE. Hypernatremia. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1493–1499.

8 Arieff AI. Central nervous system manifestations of disordered sodium metabolism. Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1984;13:269–294.

9 Snyder NA, Feigal DW, Arieff AI. Hypernatremia in elderly patients. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107:309–319.

10 Lee CT, Guo HR, Chen JB. Hyponatremia in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:264–268.

11 Hartung TK, Schofield E, Short AI, et al. Hyponatremic states following 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, ‘ecstasy’) ingestion. Q J Med. 2002;95:431–437.

12 Patel GP, Kasiar JB. Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone–induced hyponatremia associated with amiodarone. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22:649–651.

13 Ellison DH, Berl T. The syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2064–2072.

14 Adrogué HJ. Consequences of inadequate management of hyponatremia. Am J Nephrol. 2005;25:240–249.

15 Androgué HJ, Madrias NE. Hyponatremia. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1581–1589.

16 Moritz ML, Ayus JC. 100 cc 3% sodium chloride bolus: a novel treatment for hyponatremic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Des. 2010;25:91–96.