CHAPTER 48 SMALL BOWEL INJURY

Injuries to the intestines have been described since antiquity. The statement “a slight blow will cause rupture of the intestines without injury to the skin” is attributed to Aristotle, and Hippocrates was the first to describe intestinal injury from penetrating trauma. In 1275, De Salicet was the first to report lateral suture repair of an intestinal wound. In 1686, Bonet described blunt intestinal injury in a hunter who was thrown violently against a tree by a stag. Autopsy showed rupture of the terminal ileum and cecum. In 1761, Morgagni reported several instances of blunt trauma to the small intestine caused by direct blows to the abdomen. He emphasized the slow and insidious nature of abdominal signs, an observation clinically pertinent to this day. The first long term survivor after repair of a traumatic totally divided small intestine was reported in 1889 by Croft. In the early 20th century, the experience of Bedroitz during the Russo-Japanese War confirmed the advantage of early operative intervention for abdominal injuries. She positioned her operating theatre close to the frontlines and, by being able to treat casualties within 4 hours, showed improved outcomes. In the late 20th century, awareness of the benefits of early repair, coupled with the technologic advances in diagnosis, led to significant improvements in outcome. However, they also led to controversy and loss of consensus regarding both diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to patients at risk. As a result, there continue to be missteps in both diagnosis and management that require surgical vigilance.

INCIDENCE

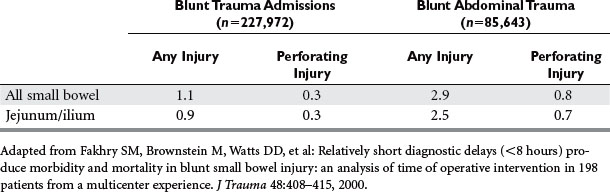

Injuries to the small intestine must be differentiated by their means of wounding. Because the small intestine occupies the largest portion of the peritoneal cavity, injuries to the small intestine are over-represented after penetrating trauma. Most series cite an incidence of involvement of the small bowel or its mesentery in 80% or greater after gunshot wounds and 25%–30% after stab wounds. In blunt trauma, although the small bowel is acknowledged as the third most common organ injured, after the liver and spleen, the incidence has recently been shown to be much less than previously thought (Table 1). The 1% incidence after blunt trauma increases to 3% in patients with blunt abdominal trauma, with the incidence of free perforation after blunt abdominal trauma still less than 1%. These figures may be misleading. Nance et al., using data from the Pennsylvania Trauma System database, showed a strong statistical correlation between the number of solid organs injured and the likelihood of associated hollow viscus injury.1 The overall incidence was 9.6%, but climbed appreciably as the number of solid organs increased, reaching 34% with three or more solid organ injuries. Isolated injury to the pancreas was associated with a 33% incidence of hollow viscus injury. Only hollow viscus injuries with an Abbreviated Injury Score (AIS) of 3 or greater were included, but the database also included injuries to the gall bladder and urinary bladder.

MECHANISM OF INJURY

There are few anatomic areas, other than the hollow viscera, where the mechanism of injury plays as important a role in determining the ease or difficulty of diagnosis or where the treatment is so well defined or confused. The small bowel may be injured by penetrating forces, including gunshot or shotgun wounds, stabbings, or impalements. Although there are recent reports attesting to the validity of nonoperative management of gunshot wounds, most surgeons hold to the belief that operation is mandated for gunshot wounds of the abdomen or where the abdomen is in jeopardy, that is, lower thoracic entry or buttock wounds. Because the likelihood of surgically significant injury exceeds 80% for gunshot wounds of the abdomen, celiotomy is indicated. Further, even when penetration of the peritoneal cavity can be excluded, blast effect leading to perforation has been described from proximity wounds, especially if the offending firearm is of high velocity (>2000 ft/sec).2 The injurious nature of shotgun wounds is directly related to the shot size and distance between the victim and the muzzle of the shotgun, with large shot size and close-range wounds being the most damaging. Stab wounds are considerably less lethal, but because most are managed selectively, the risk of missed injury is increased compared with those where protocol demands operation.

The small bowel may be injured by nonpenetrating forces. High-speed modes of transport and the omnipresent use of safety restraints have enhanced the risk of blunt small bowel injury. Whereas traffic casualties died at the scene or sustained rapidly fatal central nervous system injuries in the past, road safety efforts have reduced traffic fatalities and created different patterns of injury, one of which is the seat-belt syndrome, which includes small bowel injuries. In fact, in the multi-institutional report of Fakhry et al., a seat-belt mark was associated with an increased risk of perforated small bowel injury.3 In many cases, the mark represented incorrect usage of the safety belt, that is, too loose, too high, or poor geometry related to body size, as in children restrained by adult belts.

The pathogenesis of small bowel rupture from blunt forces is still speculative, but has variously been ascribed to crushing, shearing, or bursting forces. A violent force directly applied to the abdomen can crush the intestines between the external force and the spine. This mechanism is commonly accompanied by injuries to other organs. Shearing injuries occur from sudden deceleration with typical injuries occurring at points of relative fixation such as the ligament of Treitz and terminal ileum or at sites of adhesive bands. Some investigators have minimized this as an injury mechanism, citing the relatively even distribution of small bowel injuries in some series. The small bowel may burst if force is applied to a distended segment where ends may be temporarily closed. This explains how the small bowel may rupture after relatively minimal force, and has actually been demonstrated in the canine model. In summary, gaping small bowel disruptions with mesenteric mutilation and extensive small bowel contusion suggests a crush injury mechanism (Figure 1). Small bowel injuries with isolated clearly defined points of rupture probably represent burst injuries and shredding injuries, especially if near the ligament of Treitz, cecum, or other points of fixation, and are probably caused by shearing forces (Figures 2 and 3).

DIAGNOSIS

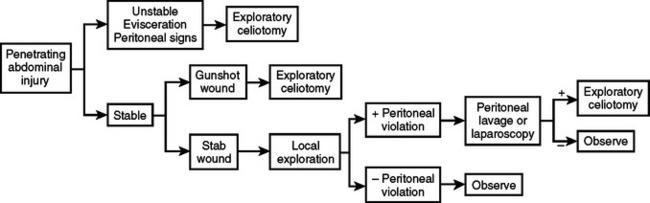

The diagnostic approach to penetrating wounds of the abdomen is slowly evolving based on newer technologies and minimally invasive surgical techniques. In 1960, Shaftan created controversy by suggesting that surgical judgment rather than mandatory celiotomy was the preferred approach to patients with penetrating trauma.4 His initial efforts slowly gained support in the management of stab wounds. Stab wounds follow the rule of thirds: one-third do not penetrate the peritoneal cavity, one-third penetrate the peritoneal cavity but do not create injury, and one-third cause injury requiring operative repair. Recognizing that a mandatory policy of celiotomy resulted in negative or nontherapeutic celiotomy in two-thirds of patients, selective management is now a common practice. In 2001, Scalea et al.5 reported a prospective series of hemodynamically stable patients with penetrating trauma studied by triple-contrast computed tomography (CT). There were 75 consecutive patients and 60% sustained gunshot or shotgun wounds. Nonoperative management was successful in 96% of patients with a negative CT scan. Despite this impressive series, most surgeons employ celiotomy for the treatment of gunshot wounds and accept a 15% negative or nontherapeutic celiotomy rate. In some institutions, both operative and selective management coexist, with surgical judgment prevailing in instances where the suspicion of intraperitoneal penetration or injury is low, that is, flank wounds and wounds confined to the liver.

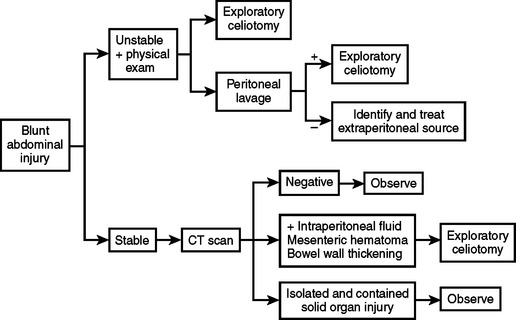

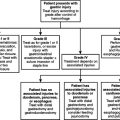

Indications for operation follow generally accepted algorithms (Figures 4 and 5). When criteria are met, most surgeons proceed with operative treatment. The emergence of experienced minimally invasive surgeons is beginning to modify indications for celiotomy after penetrating trauma, especially in wounds that potentially injure the hemidiaphragm or where abdominal penetration is in doubt. These enhanced skills have supported the evolution of laparoscopy from a primary diagnostic modality to both a diagnostic and therapeutic tool.6 Wounds to the diaphragm can be seen and repaired; wounds to other organ systems can be detected, characterized as to injury severity and, in many instances, repaired or controlled with hemostatics. Small bowel wounds remain problematic. Injuries obvious to the laparoscopic surgeon are probably detectable by other simple or less invasive techniques, that is, physical examination, CT, and diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL). Occult injuries may be initially missed regardless of the diagnostic approach, but exclusion of peritoneal penetration is useful whether by local wound exploration or direct visualization via a laparoscope.

Diagnosis of blunt small bowel injury is less obvious. Blunt small bowel injury ranges from contusion with or without serosal tear to intramural hematoma to loss of integrity of the bowel wall. The latter usually occurs immediately as a direct result of the injury, but there are many examples of delayed perforation, presumably as a result of post-traumatic ischemia leading to bowel wall necrosis. Trauma to the mesentery can have similar consequences or resolve only to cause post-traumatic stricture and delayed symptoms of intestinal obstruction. Injured patients with free perforation almost always present with abdominal pain and usually have signs of peritoneal irritation including percussion tenderness, tenderness to deep palpation, and direct and referred rebound tenderness. Operation is indicated in such situations without additional diagnostic studies. In many injured patients, the physical examination may be obscured by concurrent head injury, use of alcohol or other drugs, or associated injuries that distract the patient.7 In these instances, diagnostic studies, including CT, ultrasonography, DPL, or laparoscopy may play a role. The algorithm for the diagnosis of small bowel injury rests on certain caveats:

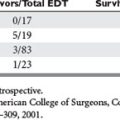

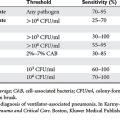

The reliability of CT scanning in the diagnosis of small bowel injury is subject to great debate. The technique of performing the CT, that is, whether or not oral contrast adds to the accuracy of the scan, is debated. What to do in the patient with free intraperitoneal fluid without solid organ injury is debated. The role of DPL as a complementary study to CT is debated.8 What is not debated, however, is the fact that patients can have a normal CT scan and still have significant small bowel injury, including perforation. CT findings suggesting small bowel injury occur in less than 50% of cases in some series (Figure 6). Because abdominal CT has become the most widely used test to detect intra-abdominal injury, there is great potential, in the patient with a negative CT, to miss the diagnosis and delay appropriate operative therapy. In 2000, Malhotra et al. cited the difference in the generations of CT scanners as impacting the ability to identify blunt small bowel injuries.9 Compared with early-generation scans, the newer helical scanners appeared to be more sensitive. Yet, there were 7 of 47 patients (15%) in his series who had negative scans and had small bowel or mesenteric injuries requiring operation. Malhotra’s experience parallels that from the EAST multiinstitutional trial, which demonstrated a 13% false negative rate for CT in the diagnosis of small bowel injury. In 2004, Allen et al. reported sensitivity and specificity of 95 and 99%, respectively, for abdominal CT scans performed with intravenous contrast alone in the diagnosis of blunt small bowel and mesentery injuries.10 However, their sample of patients with actual injury was small. In 2001, Gonzalez et al. reported the use of pre-CT DPL in a series of patients and compared the study group with a like group randomized to CT only.11 If red blood cells per millimeter cubed were higher than 20,000, a CT was performed. Those undergoing CT only and found to have free fluid without solid organ injuries were explored. Using this protocol of screening DPL, they found a low nontherapeutic celiotomy rate and improved cost-effectiveness. CT scanning has also been combined with laparoscopy in an attempt to improve diagnostic accuracy. In 2005, Mitsuhide et al. reported the use of selective laparoscopy in patients suspected of small bowel injury, either by physical examination or CT scanning.12 The laparoscopic finding of bowel perforation or ischemia mandated conversion to open operation. They concluded that CT combined with laparoscopy could prevent nontherapeutic celiotomy and reduced delay in diagnosis. In 2000, a report of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) membership regarding diagnosis and management of small bowel injuries showed a lack of confidence in any of the available diagnostic approaches.13 There was considerable variation in how to manage the neurologically impaired patient with free fluid on CT in the absence of solid organ injury (Table 2). Options ranged from observation to operation with a plurality using DPL when in doubt. In children, the presence of abdominal tenderness and isolated free intraperitoneal fluid was highly predictive of small bowel perforation.

Table 2 Patient Management: No Solid Organ Injury, Free Fluid, Unreliable Exam

| Head Injury % | Intoxication % | |

|---|---|---|

| Observe | 28 | 51 |

| Repeat computed tomography | 12 | 11 |

| Diagnostic peritoneal lavage | 42 | 26 |

| Operate | 16 | 10 |

Adapted from Brownstein MR, Bunting T, Meyer AA, Fakhry SM: Diagnosis and management of blunt small bowel injury: a survey of the membership of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma 48: 402–407, 2000.

INJURY GRADING

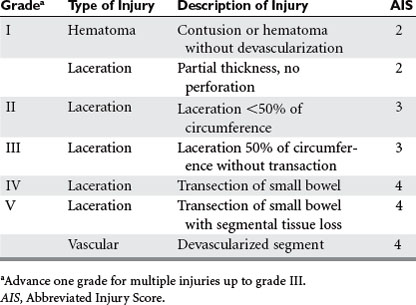

The grading of small bowel injuries is uncomplicated, but the consequences of the injury are not. The reason for this is simple—bowel injuries occur and some are not initially diagnosed. Many proceed to heal without incident, some necrose and present as an intraabdominal catastrophe, and others cause delayed symptoms, often requiring late operative treatment.14 The AAST–Organ Injury Scale is depicted in Table 3. Note that grades 2–4 correspond to free perforation and are likely to be encountered immediately or soon after presentation. Grade 5 injuries, transection with segmental tissue loss and/or devascularization, may be apparent or occult, but both cause loss of bowel integrity and require small bowel resection. Somewhere in the scheme of things, but still unclassified, rests the partial devascularization injury without full thickness necrosis that heals by stricture and causes delayed obstructive symptoms. Operation is almost always required to deal with this problem.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

In most instances, surgical management means operative management. Nonetheless, there is a definite role for surgical judgment to decide the need for resection, the extent of resection, and the method of repair and/or resection. Small bowel injuries occur as isolated injuries but they more commonly coexist with other intra-abdominal injuries from both penetrating or blunt injury mechanisms. Surgical decision making is critical in the management of associated injuries and whether to employ damage control. In 2000, Hackam et al. compared small bowel–injured patients both with and without other intra-abdominal injuries.15 Although the presence of other injuries led to earlier diagnosis and celiotomy, associated injuries adversely affected mortality, length of hospital stay (LOS), and intra-abdominal complications.

Repair is best performed by direct suture. If resection is indicated, stapler and hand-sewn techniques of anastomosis appear to be equally effective. However, both forms of resection have higher complication rates than repair. Therefore, injuries amenable to suture repair should be repaired rather than resected unless there are multiple proximity wounds that are technically easier to include in a limited resection than repair individually. In the damage control mode, wounds and lacerations are closed rapidly with a stapler to prevent continued soiling. No definitive anastomoses are performed.

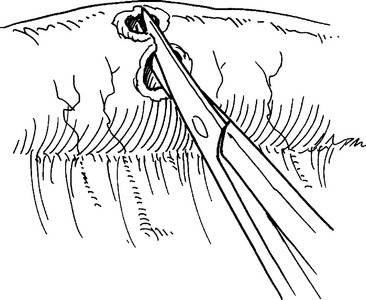

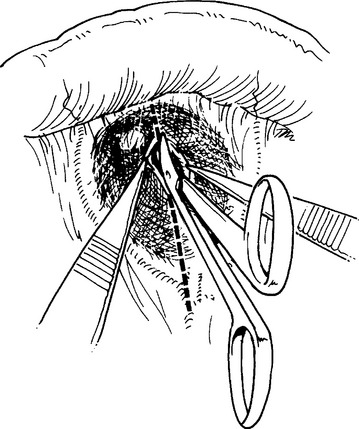

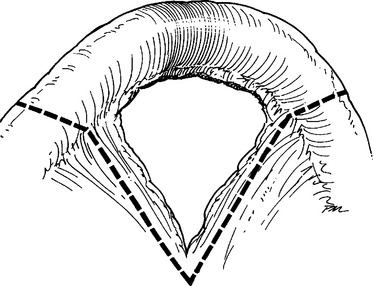

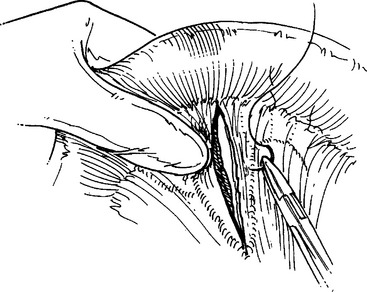

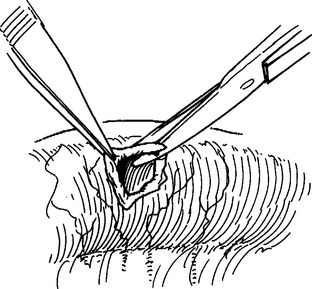

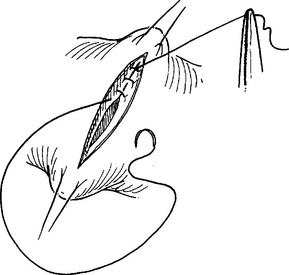

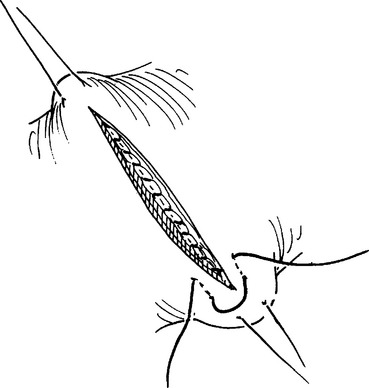

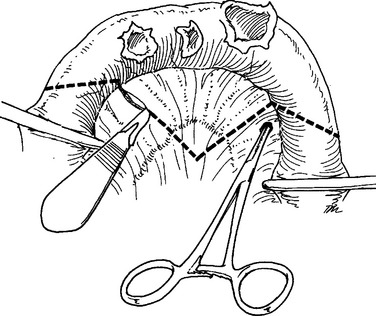

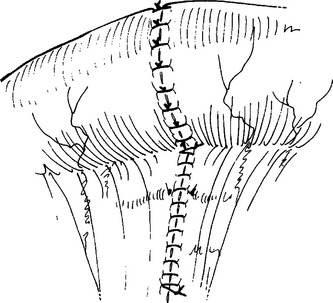

Celiotomy for trauma must include an initial exploration to control active hemorrhage followed by a systematic inspection to identify all injuries. Injuries missed at celiotomy are the most lethal missed injuries. Therefore, every effort should be made to identify all intra-abdominal injuries, especially in a damage control situation where continued contamination predicts poor outcome. Soiling from hollow viscus injuries should be isolated with noncrushing intestinal clamps or controlled with the assistant’s thumb and forefinger. Alternately, Babcock clamps can be applied. After the intestinal tract is examined from gastroesophageal junction to rectum, injuries should be counted and mentally noted or identified with tag sutures. Areas of hematoma should be carefully inspected. Most are limited to serosal injuries and are best treated by imbricating the bordering serosal margins. True intramural hematomas require surgical judgment. If limited in extent and nonexpanding, the hematoma will likely resolve on its own and does not require specific therapy. Large or expanding intramural hematomas, or those in which the viability of the involved intestinal segment cannot be determined, require intervention. Both hematoma evacuation and resection of the involved segment have been recommended. This author favors the latter. Perforations should be carefully debrided back to viable tissue, splayed with corner stay sutures and closed transversely in two layers (Figures 7, 8, and 9). Perforations that are closely opposed should be converted to a single defect and closed in like manner (Figure 10). Multiple perforations within a short segment are best treated by resection and anastomosis (Figure 11). The mesenteric defect should be closed in continuity (Figure 12).

Figure 7 Perforations carefully debrided back to viable tissue.

(From Maull KI: Stomach, small bowel and mesentery injury. In Champion HR, Robbs JV, Trunkey DD, editors: Rob and Smith’s Operative Surgery: Trauma Surgery, 4th ed. London, Butterworth-Heinemann, London, pp. 401–413.)

Figure 8 Perforations splayed with corner stay sutures.

(From Maull KI: Stomach, small bowel and mesentery injury. In Champion HR, Robbs JV, Trunkey DD, editors: Rob and Smith’s Operative Surgery: Trauma Surgery, 4th ed. London, Butterworth-Heinemann, London, pp. 401–413.)

Figure 9 Perforations closed transversely in two layers.

(From Maull KI: Stomach, small bowel and mesentery injury. In Champion HR, Robbs JV, Trunkey DD, editors: Rob and Smith’s Operative Surgery: Trauma Surgery, 4th ed. London, Butterworth-Heinemann, London, pp. 401–413.)

Figure 11 Multiple perforations within a short segment are best treated by resection and anastomosis.

(From Maull KI: Stomach, small bowel and mesentery injury. In Champion HR, Robbs JV, Trunkey DD, editors: Rob and Smith’s Operative Surgery: Trauma Surgery, 4th ed. London, Butterworth-Heinemann, London, pp. 401–413.)

Figure 12 The mesenteric defect should be closed in continuity.

(From Maull KI: Stomach, small bowel and mesentery injury. In Champion HR, Robbs JV, Trunkey DD, editors: Rob and Smith’s Operative Surgery: Trauma Surgery, 4th ed. London, Butterworth-Heinemann, London, pp. 401–413.)

Injuries to the mesentery vary from small hematomas to extensive life-threatening avulsion injuries. Large or expanding mesenteric hematomas and those adjoining the intestinal wall should be explored and direct vascular control established by suture ligature (Figure 13). The integrity of the intestinal wall should be confirmed or repaired, as needed. Mesenteric tears may cause ischemia of the involved intestinal segment and resection may be necessary (Figure 14). All tears must be closed with sutures (Figure 15).

COMPLICATIONS

Complications after small bowel injury differ by injury mechanism. In blunt trauma, the principal concern is delay in diagnosis. In 2000, Fakhry et al., in a multicenter study of eight trauma centers, reported a statistically significant increased risk of wound infection, wound dehiscence, intra-abdominal abscess, adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and sepsis in patients with isolated small bowel perforations operated on more than 24 hours after injury compared with those undergoing operation less than 8 hours after injury.16 Fang et al. reported a dramatic increase in complications if surgery was delayed more than 24 hours.17 In children sustaining blunt small bowel rupture, delay in diagnosis more than 24 hours did not result in increased morbidity or mortality as reported by Bensard et al.18

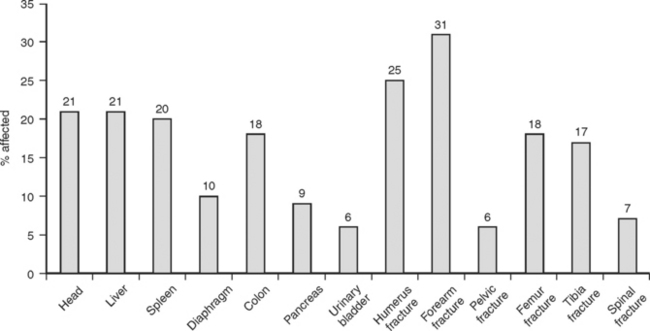

Complications are also related to associated injuries and to whether management of the small bowel injury requires repair or resection. Associated multisystem injuries occur in as many as 70% of cases after blunt trauma, and often dictate not only the occurrence of complications, but also the eventual outcome19(Figure 16). Anastomosis-related complications include leaks, enterocutaneous fistula, and intraabdominal abscess.20 These complications are uncommon but exceed the incidence after simple repair. Damage control predicts an increased likelihood of anastomosis-related complications.

Figure 16 Typical injuries accompanying blunt small bowel trauma.

(Adapted from Neugebauer H, Wallenboeck E, Hungerford M: Seventy cases of injury of the small intestine caused by blunt abdominal trauma: a retrospective study from 1970 to 1994. J Trauma 46:116–121, 1999.)

Late complications of bowel obstruction relate to adhesions and ischemic stenosis from unrecognized small bowel or mesenteric injury. In the latter circumstance, symptoms usually appear within 6 weeks postinjury and vary from vague abdominal pain to frank obstruction.21 Resection is necessary to relieve the obstruction.

MORTALITY

Although reported mortalities have reached 25% or higher in some series, the consensus mortality after blunt small bowel injury is approximately 10%. In the multicenter study reported by Fakhry et al., there was no difference in mortality between patients with isolated small bowel injury and those who incurred small bowel injury in the setting of multiple other injuries.16 Delays in diagnosis were directly related to almost half the deaths in this series. In fact, delays exceeding as little as 8 hours resulted in increased morbidity and mortality.

Mortality after penetrating injury is most commonly related to injury to other intraperitoneal and/or retroperitoneal injuries.22

1 Nance ML, Peden GW, Shapiro MB, et al. Solid viscus injury predicts major hollow viscus injury in blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1997;43:618-623.

2 Velitchkov NG, Losanoff JE, Kjossev KT, et al. Delayed small bowel injury as a result of penetrating extraperitoneal high-velocity ballistic trauma to the abdomen. J Trauma. 2000;48:169-170.

3 Fakhry SM, Watts DD, Luchette FA. Current diagnostic approaches lack sensitivity in the diagnosis of perforated small bowel injury: analysis from 275,557 trauma admissions form the EAST multi-institutional HVI trial. J Trauma. 2003;54:295-306.

4 Shaftan GW. Indications for operation in abdominal trauma. Am J Surg. 1960;99:657-664.

5 Chiu WC, Shanmuganathan K, Mirvis SE, Scalea TM. Determining the need for laparotomy in penetrating torso trauma: a prospective study using triple-contrast enhanced abdominopelvic computed tomography. J Trauma. 2001;51:860-869.

6 Sinha R, Sharma N, Joshi M. Laparoscopic repair of small bowel perforation. J Soc Laparoendosc Surg. 2005;9:399-402.

7 Maull KI, Reath DB. Impact of early recognition on outcome in nonpenetrating wounds of the small bowel. South Med J. 1984;77:1075-1077.

8 Brasel KJ, Olsen CJ, Stafford RE, Johnson TJ. Incidence and significance of free fluid on abdominal computed tomographic scan in blunt trauma. J Trauma. 1998;44:889-892.

9 Malhotra AK, Fabian TC, Katsis SB, et al. Blunt bowel and mesenteric injuries: the role of screening computed tomography. J Trauma. 2000;48:991-1000.

10 Allen TL, Mueller MT, Bonk T, et al. Computed tomographic scanning without oral contrast solution for blunt bowel and mesenteric injuries in abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 2004;56:314-322.

11 Gonzalez RP, Ickler J, Gachassin P. Complementary roles of diagnostic peritoneal lavage and computed tomography in the evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 2001;51:1128-1136.

12 Mitsuhide K, Junichi S, Atsushi N, et al. Computed tomography scanning and selective laparoscopy in the diagnosis of blunt small bowel injury: a prospective study. J Trauma. 2005;58:696-703.

13 Brownstein MR, Bunting T, Meyer AA, Fakhry SM. Diagnosis and management of blunt small bowel injury: a survey of the membership of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma. 2000;48:402-407.

14 Kaban G, Somani RA, Carter J. Delayed presentation of small bowel injury after blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 2004;56:1144-1145.

15 Hackam DJ, Ali J, Jastaniah SS. Effects of other intra-abdominal injuries on the diagnosis, management and outcome of small bowel injuries. J Trauma. 2000;49:606-610.

16 Fakhry SM, Brownstein M, Watts DD, et al. Relatively short diagnostic delays (<8 hours) produce morbidity and mortality in blunt small bowel injury: an analysis of time of operative intervention in 198 patients from a multicenter experience. J Trauma. 2000;48:408-415.

17 Fang JF, Chen RJ, Lin BC, et al. Small bowel perforation: is urgent surgery necessary? J Trauma. 1999;47:515-520.

18 Bensard DD, Beaver B, Besner GE, Cooney DR. Small bowel injury in children after blunt abdominal trauma: is diagnostic delay important? J Trauma. 1996;41:476-483.

19 Neugebauer H, Wallenboeck E, Hungerford M. Seventy cases of injury of the small intestine caused by blunt abdominal trauma: a retrospective study from 1970 to 1994. J Trauma. 1999;46:116-121.

20 Maull KI. Stomach, small bowel and mesentery injury. In: Dudley H, Carter D, Russell RC, editors. Operative Surgery. London: Butterworths; 1989:401-413.

21 Kirkpatrick AW, Baxter KA, Simons RK, et al. Intra-abdominal complications after surgical repair of small bowel injuries: an international review. J Trauma. 2003;55:399-406.

22 Stevens SL, Maull KI. Small bowel injuries. Surg Clin North Am. 1990;70:541-560.