Small bowel and operations for obesity

EXAMINATION OF THE SMALL BOWEL

Normal appearance

1. The duodenum [From Greek: duodekadaktulon = 12 fingers (breadth)] is 25 cm long. Apart from the proximal 2–3 cm, it is retroperitoneal. The remaining small bowel, which has a mesentery, is variable in total length (about 3–5 m) and difficult to measure with accuracy in vivo. It is arbitrarily divided into a proximal 40%, the jejunum (Latin: jejunus = hungry, empty), and a distal 60%, the ileum (Greek: eilios = twisted). On palpation the jejunal wall is thicker than that of the ileum, so that the examining fingers gain the impression of a double layer, rather like feeling a shirt through the sleeve of a jacket.

2. Examine the duodenal loop. Locate the duodenojejunal flexure by displacing the transverse colon upwards and tracing the coils of jejunum proximally to the ligament of Treitz. Pick up the small bowel at the duodenojejunal flexure and feed it through your fingers down to the ileocaecal valve. Note the diameter and contents of the bowel and the thickness and colour of its wall.

3. Examine the small-bowel mesentery throughout. Its thickness varies with the patient’s adiposity. In a thin patient mesenteric lymph nodes can often be seen: determine whether the nodes are enlarged or inflamed.

Abnormalities

1. Diverticula. These are common. Meckel’s diverticulum, which arises from the distal ileum, is considered below. Acquired diverticula may affect the duodenum, jejunum and to a lesser extent the ileum, and are frequently multiple. Do not remove incidental diverticula unless they are inflamed, bleeding or appear diseased.

2. Inflammation. Crohn’s disease may affect any part of the alimentary tract but especially the terminal ileum. Affected segments of bowel are inflamed, thickened and narrowed, and often covered with fibrinous exudate. The mesentery is thickened and the mesenteric fat often extends over the serosa of the bowel towards the anti-mesenteric border (fat wrapping). Adjacent lymph nodes are often enlarged. Look for evidence of disease elsewhere in the small and large bowel. Segmental resection is often required for chronic Crohn’s enteritis. Tuberculous and Yersinial infection can produce similar changes of ileitis; if in doubt remove a lymph node for bacteriological and histological examination. Coeliac disease predominantly affects the jejunum. The diagnosis is indicated by dilatation of subserous and mesenteric lymphatics, thinning and pigmentation of the bowel wall and splenic atrophy. Severe refractory coeliac disease may cause ulcerative jejunitis and predispose to small bowel lymphoma.1 Full-thickness biopsy is usually required to make this diagnosis (see below). Small-bowel ulcers and strictures may occur spontaneously, follow radiotherapy or transient strangulation in an external hernia or after the ingestion of potassium tablets.

3. Infarction. The viability of the small bowel must be carefully checked after reduction of a strangulated hernia or untwisting of a volvulus in adhesional obstruction. Any frankly necrotic or perforated loops should be excised. If you are in doubt about the viability of a dusky segment, return it to the abdomen and wait for 5 minutes (timed by the clock). The return of a shiny, pink appearance, pulsation of the mesenteric vessels and peristalsis across the affected segment indicate viability. If doubt persists, resect.

4. Tumours. Serosal deposits occur in carcinomatosis peritonei and may cause kinking and obstruction of the small bowel, requiring side-to-side bypass (see below). Primary neoplasms are less common. Benign tumours such as adenoma, leiomyoma, lipoma and Peutz-Jeghers hamartomas can cause intussusception. Carcinoid tumours favour the ileum, but may be multiple and metastasizing; they are hard with a yellowish cut surface. Other malignant tumours comprise adenocarcinoma, lymphoma and leiomyosarcoma in that order of prevalence. Primary neoplasms should be resected or, if unresectable, bypassed and biopsied.

Biopsy

1. Duodenal lesions can be biopsied endoscopically under direct vision.

2. The small intestine can be examined using flexible endoscopy or capsule endoscopy. Capsule endoscopy is now widely used clinically, complementing other enteroscopic techniques.1 It employs a capsule containing a digital camera with a radio transmitter, an external receiving antenna and a computer workstation for review of images. The technique is increasingly used for the diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, iron-deficiency anaemia and Crohn’s disease.2,3 Biopsy of any identified abnormalities, on the other hand, requires small bowel enteroscopy.

3. Operative biopsy of the small intestine is seldom indicated. It is usually possible to excise the segment of bowel in question, and intestinal biopsy should be avoided in Crohn’s disease. If a full-thickness biopsy is required, however, the incision should be closed in two layers in the same fashion as an intestinal anastomosis.

4. Mesenteric lymph nodes can be biopsied with relative ease, either laparoscopically or at open surgery. Where possible, select a node close to the bowel wall and avoid dissecting deep into the root of the mesentery. Carefully incise the peritoneum and dissect out the entire node, using diathermy to coagulate small blood vessels.

REFERENCES

1. Rubio-Tapia A, Murray JA. Classification and management of refractory coeliac disease. Gut 2010;59(4):547–57.

2. Liao Z, Gao R, Xu C, et al. 2010 Indications and detection, completion, and retention rates of small-bowel capsule endoscopy: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;71(2):280–6.

3. Maieron A, Hubner D, Blaha B, et al. Multicenter retrospective evaluation of capsule endoscopy in clinical routine. Endoscopy 2004;36:864–8.

INTESTINAL ANASTOMOSIS

General principles

1. Several hundred intestinal anastomoses are carried out each week in Britain, and the vast majority heal rapidly by primary intention.

2. Remember that most of the intestinal tract is contaminated with bacteria. Take appropriate precautions against disseminating faecal organisms before dividing and re-suturing the bowel; clamps are usually indicated to prevent spillage of faeces or small bowel contents.

3. Ensure that the bowel ends are pink and bleeding freely, and leave the mesentery attached to the bowel right up to the point of intestinal transection. If either cut end is bruised or dusky, it is usually sensible to sacrifice a few more centimetres of intestine, even if, in the case of the large bowel, this requires further mobilization.

4. Tension usually results from inadequate mobilization, especially of the colon. Though readily avoidable, twisting of the mesentery can also render an anastomosis ischaemic. Repair mesenteric/mesocolic defects after completing an intestinal anastomosis to prevent postoperative internal herniation, but take care not to compromise the vessels supplying the bowel ends.

5. Distended loops of bowel are heavy and difficult to handle. Moreover, healing is impaired because the bowel wall is somewhat ischaemic. Distended small bowel may be decompressed by milking contents upwards into the reach of the nasogastric tube or by enterotomy and insertion of a sucker (see below). Gaseous distension of the large bowel can be relieved by introducing a needle obliquely through its wall.

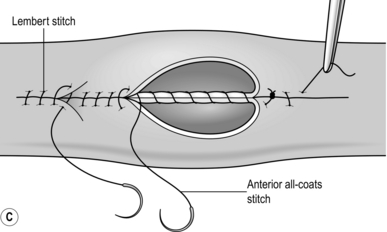

Hand-suturing techniques

1. Traditionally, bowel is united in two layers, using absorbable suture material such as polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) for the inner, all-coats layers and an outer stitch, named after its inventor in 1826, the Parisian surgeon Antoine Lembert (1802–1851), to join the seromuscular layers. More recently, one-layered anastomoses have gained popularity and have proved safe. They are used in colorectal, small bowel and bilio-enteric anastomoses and in oesophago-jejunostomy.

2. Surgeons have long disputed the best suture material, the best type of stitch and the best methods of fashioning a suture line. These technical points are less important than the principle stated above: to achieve accurate and tension-free coaptation of two healthy mucosal surfaces. Nevertheless, each surgeon develops his own variations of technique which he believes to be the most appropriate. As an assistant, therefore, follow the method of your present chief and aim to experience a number of methods before you select one for yourself.

3. Surgical trainees are often uncertain whether to use continuous or interrupted sutures in a given situation. A continuous (running) stitch is undoubtedly quicker and it achieves good haemostasis. It can be used for straightforward gastric, enteric and colonic anastomoses.

4. Interrupted sutures allow greater precision and may be more convenient than a continuous stitch when there is marked disparity in the size of the bowel ends to be united or the anastomosis is technically difficult. In inaccessible situations, such as a colorectal anastomosis deep in the pelvis or hepaticojejunostomy, it may be wise to insert the entire posterior row of interrupted sutures before trying any individual stitch.

5. Many surgeons routinely use two layers of continuous absorbable sutures for gastric and intestinal anastomoses. If impaired healing is anticipated, as in Crohn’s disease, an inner layer of continuous Vicryl and an outer layer of interrupted 2/0 polyester (Ethibond) or similar non-absorbable suture may provide additional security. Non-absorbable sutures are often also used when joining small bowel to the oesophagus, pancreas or rectum.

6. Whichever type of suture and suture material you employ, take care to achieve the correct degree of tension when pulling through and tying the stitch. Insert each stitch separately and invert the bowel edges as the suture is tightened. Once the bowel edge is inverted, prevent the suture material from slipping by getting your assistant to ‘follow’, keeping the tension on the suture already placed. Alternatively, follow for yourself, using the taut suture as a means of steadying the bowel against the thrust of the needle. The objective is a snug, watertight anastomosis. Excessive tension risks strangulating the bowel incorporated in the stitch and perhaps causing subsequent leakage.

7. Do not place the sutures so close to the edge of the bowel that they might tear out or so deep that they turn in an enormous cuff of tissue and narrow the bowel: usually 3–5 mm is about the correct depth of ‘bite’. Be sure that the all-coats suture does in fact incorporate all coats of the bowel wall. The best way to master these important technical points is to assist at, and then perform under supervision, a number of intestinal anastomoses.

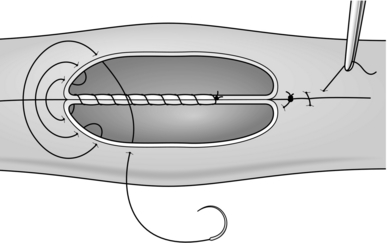

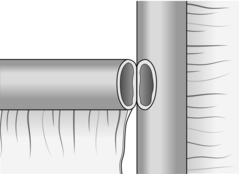

8. The seromuscular stitch unites the adjacent bowel walls outside the all-coats stitch. Sometimes the posterior seromuscular layer is inserted before opening the gut, as in side-to-side anastomoses (Fig. 11.1). After the all-coats stitches have been inserted, carry the seromuscular sutures round the ends of the anastomosis and across the front wall, ultimately encircling the anastomosis so that the all-coats stitches can no longer be seen. For end-to-end anastomoses in small and large intestine it may be simpler to complete the all-coats layer before placing any Lembert sutures. Thereafter, the seromuscular layer can be inserted all the way round by rotating the bowel.

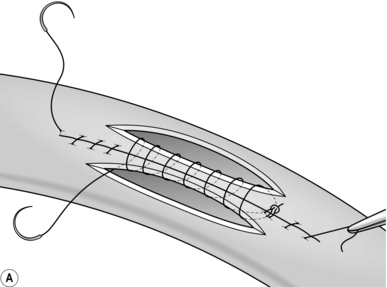

9. There are many ways of inserting the all-coats stitch; two popular methods are described here:

Continuous over–and–over suture. Approximate the two edges of cut bowel. Starting at one end, insert a corner stitch from outside to in, then over the adjacent edges of bowel and out through the other corner. Tie the suture and clip the short end. Pass the stitch back through the nearest bowel wall, over the contiguous cut edges and back through the full thickness of both walls. Continue over-and-over stitches to the opposite corner (Fig. 11.2A). After the last stitch is inserted right into the corner, take it back through the nearest corner leaving a loop on the mucosa so that the stitch emerges from the outer wall of the bowel (Fig. 11.2B). Now sew the front walls together by passing the stitch over and over, from out to in and then from in to out (Fig. 11.2C). Continue until the anastomosis has been encircled and the edges inverted, then tie off the ends of suture material. This over-and-over stitch is haemostatic.

Continuous over–and–over suture. Approximate the two edges of cut bowel. Starting at one end, insert a corner stitch from outside to in, then over the adjacent edges of bowel and out through the other corner. Tie the suture and clip the short end. Pass the stitch back through the nearest bowel wall, over the contiguous cut edges and back through the full thickness of both walls. Continue over-and-over stitches to the opposite corner (Fig. 11.2A). After the last stitch is inserted right into the corner, take it back through the nearest corner leaving a loop on the mucosa so that the stitch emerges from the outer wall of the bowel (Fig. 11.2B). Now sew the front walls together by passing the stitch over and over, from out to in and then from in to out (Fig. 11.2C). Continue until the anastomosis has been encircled and the edges inverted, then tie off the ends of suture material. This over-and-over stitch is haemostatic.

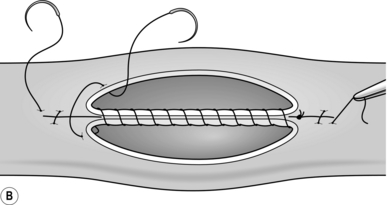

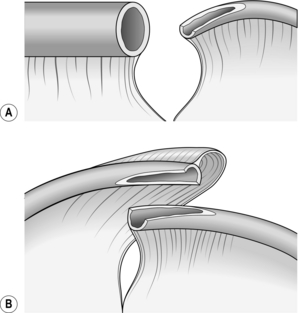

Continuous over–and–over plus Connell suture. Commence in the middle of the posterior wall by placing a stitch between the adjacent cut edges of bowel and tying it on the luminal surface. Now continue towards one corner with over-and-over stitches. At the corner the needle passes from in to out on the nearside cut surface, then crosses to the far edge and is passed in and out to leave a loop on the mucosa (Fig. 11.3). The needle returns to the near edge and another loop-on-the-mucosa stitch (named after the American surgeon Gregory Connell born 1875, who popularized it) is inserted. These Connell stitches turn the corner neatly. Once you are round the corner, leave this stitch and return to the middle of the posterior wall. Use a new length of suture material, unless there is a needle at each end of the original length. Insert and tie a stitch close to the site of the original knot, and proceed towards the opposite corner, using Connell sutures to negotiate the corner again. Once round the corner, return to over-and-over stitches. Tie the ends of suture material together where they meet in the middle of the anterior wall.

Continuous over–and–over plus Connell suture. Commence in the middle of the posterior wall by placing a stitch between the adjacent cut edges of bowel and tying it on the luminal surface. Now continue towards one corner with over-and-over stitches. At the corner the needle passes from in to out on the nearside cut surface, then crosses to the far edge and is passed in and out to leave a loop on the mucosa (Fig. 11.3). The needle returns to the near edge and another loop-on-the-mucosa stitch (named after the American surgeon Gregory Connell born 1875, who popularized it) is inserted. These Connell stitches turn the corner neatly. Once you are round the corner, leave this stitch and return to the middle of the posterior wall. Use a new length of suture material, unless there is a needle at each end of the original length. Insert and tie a stitch close to the site of the original knot, and proceed towards the opposite corner, using Connell sutures to negotiate the corner again. Once round the corner, return to over-and-over stitches. Tie the ends of suture material together where they meet in the middle of the anterior wall.

Mechanical stapling techniques

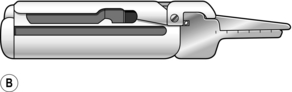

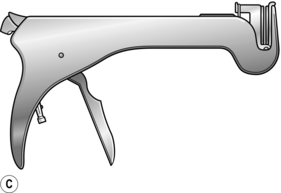

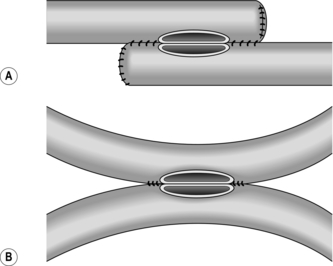

1. Stapling devices can be used to carry out most types of gastrointestinal anastomoses. Disposable and angled instruments are available for use in particular circumstances, and the metal staples come in different lengths to accommodate the different tissue thicknesses encountered. For end-to-end anastomosis (e.g. colorectal, oesophagojejunal) a circular stapling gun (Fig. 11.4A) is introduced into the intestinal lumen downstream, brought out through the distal cut end of bowel and then insinuated into the proximal cut end.

Choose the largest anvil that will fit comfortably into the proximal lumen. Tightly snug the proximal and distal gut around the central rod using a polypropylene purse-string suture, and then approximate the anvil to the cartridge by closing the instrument. When the gun is fired, a circular double row of titanium staples is inserted and at the same time a complete 5-mm rim of each bowel end (the ‘doughnut’) is resected. Withdraw the machine and check the ‘doughnuts’ to confirm that they are complete and that the anastomosis is perfect.

2. For side-to-side anastomoses a different instrument called a linear stapler/cutter is used. It resembles a pair of scissors (Fig. 11.4B). One ‘blade’ is inserted into each of the two intestinal segments to be united, and the blades are closed. Firing the gun advances a knife, which divides the adjacent surfaces of bowel between three parallel rows of staples.

The resulting opening can then either be sutured or stapled closed using a further staple cartridge.

3. Stapling devices reduce the time involved in creating an anastomosis and are used extensively in laparoscopic bariatric and oesophago-gastric surgery.

Types of anastomosis

End-to-end anastomosis

1. This is the simplest way of restoring intestinal continuity after partial enterectomy where there is little or no size disparity. After removal of the resected specimen, clean and approximate the bowel ends. The anastomosis is usually created in one layer, using interrupted absorbable sutures (e.g. 2/0 or 3/0 Vicryl).

Interrupted sero–muscular suture. Insert three stay sutures from out to in and in to out evenly spaced around the bowel circumference. Clip the ends and get your assistant to hold the clips to exert traction on the cut edges of bowel. This causes the bowel lumen to adopt a triangular appearance (Fig. 11.5). Between two of the stay sutures, held taught, insert a row of sutures 2–3 mm apart, taking serosa and muscularis only and tying the knots on the serosal surface.

2. Now rotate the anastomosis using the stays and place a further row of sutures between the next adjacent stay sutures. Finally turn the anastomosis over and suture the third side of the triangle. All knots should lie uniformly on the outside of the anastomosis.

Oblique anastomosis

1. When the ends of bowel are disproportionate in size, they may be matched by incising the antimesenteric border of the narrow bowel longitudinally (Fig. 11.6A).

2. This manoeuvre is useful in joining obstructed bowel to collapsed bowel or ileum to colon. In neonates with congenital intestinal atresia, the lumen of the distal bowel is particularly narrow and this type of ‘end-to-back’ anastomosis is necessitated. When two segments of narrow intestine must be united, they may both be opened along their antimesenteric borders, which are then joined back-to-back (Fig. 11.6B). The mesenteries are now on opposite sides of the anastomosis and cannot always be neatly approximated.

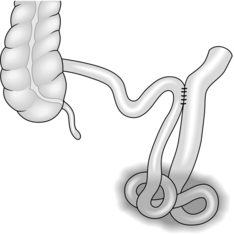

End-to-side anastomosis

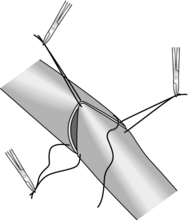

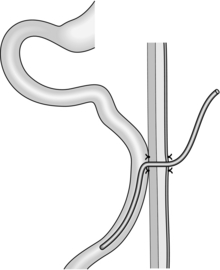

1. This is most commonly used when creating a Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Approximate the cut end to the side of bowel to which it will be joined and insert a posterior seromuscular suture (Fig. 11.7).

Fig. 11.7 End-to-side anastomosis.

2. Incise the antimesenteric border of the side of bowel to accommodate the cut end. Insert the all-coats stitch as before, remove the clamps and complete the seromuscular stitch. Lastly, join the cut edge of mesentery to the side of the intact mesentery.

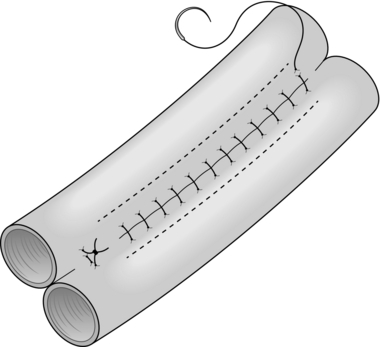

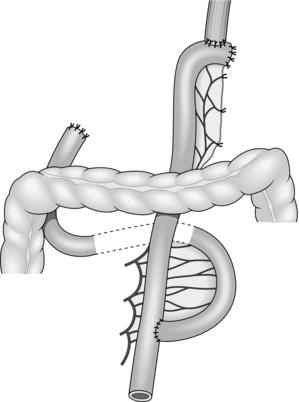

Side-to-side anastomosis

1. This can be used to joint two loops of bowel without resection, or to unite intestine to stomach, bile duct, etc. (Fig. 11.8).

2. It may also be employed as an alternative to end-to-end anastomosis after intestinal resection, in which case the cut ends of bowel should first be closed and invaginated. The advantages of the side-to-side anastomosis are that the segments of bowel to be united have no interruption to their blood supply at all and that the incisions can be made exactly congruous. The disadvantages are that there are more suture lines involved and that there may be some degree of stasis and bacterial overgrowth.

3. Lay the segments to be joined side by side in contact for 8–10 cm and insert a posterior seromuscular stitch. Incise the antimesenteric borders for about 5 cm and insert an all-coats stitch. Remove the clamps and complete the anterior seromuscular layer of stitches. When side-to-side anastomosis follows bowel resection, suture the cut edge of mesentery to the adjacent intact mesentery on each side of the anastomosis.

ENTERECTOMY (SMALL-BOWEL RESECTION)

Appraise

1. Resection is often indicated for congenital lesions of the small bowel such as atresia and duplication; traumatic perforation; critical ischaemia from mesenteric trauma, strangulation or arteriosclerosis; Crohn’s disease or other cause of stricture; tumours of the bowel or its mesentery. Resection is sometimes indicated for fistula, diverticulitis, intussusception and a symptomatic blind loop. Small portions of the duodenum and ileum are removed during partial gastrectomy and right hemicolectomy respectively.

2. There are several reasons for being conservative in the management of Crohn’s disease: the indolent nature of the disease, its relapsing course and its strong tendency (> 50%) to recur anywhere in the intestinal tract, but especially at and just proximal to the anastomosis. Despite many advances in the treatment of Crohn’s disease, the course of the disease in any given patient remains unpredictable. A multivariate analysis has shown that the only independent predictors of earlier postoperative recurrence after initial operation are an initial presentation with peritonitis secondary to perforation, and a longer preoperative disease duration.1

3. On the other hand, most patients with chronic Crohn’s enteritis eventually require resection of the affected segment because of subacute obstruction, fistula or abscess. Bypass is obsolete: although it may achieve remission of active disease in the defunctioned segment, bacterial overgrowth of the blind loop may aggravate diarrhoea and there is a long-term risk of carcinoma. For short stenotic areas of bowel strictureplasty (see below) is an alternative to resection.

4. When operating for radiation enteropathy, establish the extent both of the original cancer and of the radiation damage. Where possible, avoid bypass or exclusion procedures: the defunctioned bowel may still give rise to problems such as bleeding and fistula. Wide resection is the optimal approach, ensuring that at least one side of the subsequent anastomosis employs healthy, non-irradiated, bowel.

Prepare

1. In the presence of an obstructing lesion, ensure that the patient is adequately resuscitated before operation with nasogastric intubation and intravenous rehydration.

2. Healthy ileum has a resident bacterial flora, and in the presence of obstruction the entire small bowel may be colonized. It is sensible to employ appropriate prophylactic antibiotic cover, such as a cephalosporin plus metronidazole given preoperatively in a single injection, in all operations likely to involve intestinal resection.

3. Nutritional status may be impaired in some patients requiring small-bowel resection, for example those with Crohn’s disease, cancer, radiation enteropathy or enterocutaneous fistula. In the absence or obstruction or fistula, supplemental enteric feeds may reverse the nutritional defect, but some patients require a period of preoperative parenteral nutrition.

Access

1. Employ a midline incision that skirts the umbilicus and can be extended in either direction as necessary.

2. Remember that the small bowel quite often adheres to the back of a previous laparotomy incision, so take particular care during abdominal re-entry. An accidental perforation is unlikely to be located in a segment of bowel you intended to remove.

Assess

1. Expose and examine the entire small bowel. Continue by examining the stomach, large bowel and remaining abdominal viscera.

2. If a loop of small bowel has been strangulated in an external hernia, release the obstruction and check the viability of the bowel after allowing a period of 5 minutes for possible recovery in doubtful cases.

3. Do not gratuitously sacrifice healthy bowel, particularly terminal ileum which has specialized transport functions. Except when operating for primary malignant tumours it is quite unnecessary to excise a deep wedge of mesentery, which might increase the extent of small bowel requiring removal. In Crohn’s disease do not remove more than a few centimetres of gut on either side of the affected segment, but include any fistulas or sinuses. It is more than likely that further resection will be required in future, and microscopic inflammation of the bowel at the resection margin does not appear to increase subsequent anastomotic recurrence. Formal right hemicolectomy is unnecessary for Crohn’s disease of the terminal ileum; undertake a limited ileocaecal resection.

4. Sometimes a partial resection of small bowel can be performed, leaving the mesentery intact. Appropriate conditions include Richter’s hernia, Meckel’s diverticulum and small benign tumours arising on the antimesenteric border.

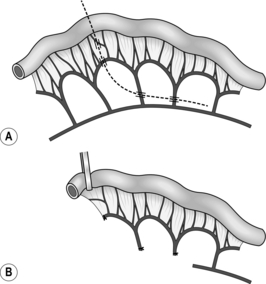

Standard resection

1. Determine the proximal and distal sites for dividing the bowel, and select the line of vascular section in between; keep close to the bowel wall (Fig. 11.9) except when resecting a neoplasm (Fig. 11.10). Incise the peritoneum along this line on each aspect of the mesentery. This manoeuvre is most easily accomplished by inserting one blade of a pair of fine, curved scissors beneath the peritoneum and cutting superficially to expose the mesenteric vessels.

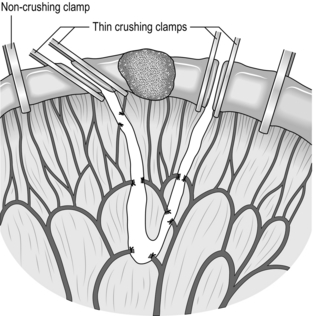

Fig. 11.10 Resection of a small-bowel tumour. A deeper wedge of mesentery is included than in operations for benign disease (see Fig. 11.9). As before, the narrower segment of bowel (on the left) is transected obliquely, removing more of the mesenteric border with the specimen.

2. Using small artery forceps, create a small mesenteric window right next to the bowel wall at each point chosen for intestinal transection. Starting at one end, insinuate a curved artery forceps through this window and back through the mesentery, denuded of peritoneum, 1–2 cm away, thus isolating a small leash of mesentery with its contained vessels. Divide the vessels between artery forceps, ligating the mesentery beneath each pair of forceps using 2/0 or 3/0 Vicryl ties, according to the thickness of the mesentery. Proceeding in this manner, divide the mesentery right up to the bowel wall at the further end of the line of peritoneal incision. Take care in placing and tying each ligature: if the knot slips, there can be troublesome haemorrhage.

3. Apply four intestinal clamps (Fig. 11.9). The first two clamps are crushing clamps (Payr’s, Lang Stevenson’s or Pringle’s). They should be applied obliquely at the points of intended intestinal transection, so that slightly more of the antimesenteric border is resected than of the mesenteric border; the obliquity reduces the risk of a tight anastomosis. Now apply a non-crushing clamp about 5 cm outside each crushing clamp, having milked the intervening bowel free of contents.

4. Place a clean gauze swab beneath the clamps at each end to catch spills, and divide the bowel with a knife flush against the outer aspect of each crushing clamp. Place the specimen and the soiled knife in a separate dish, which is then removed.

5. Cleanse each bowel end, using small swabs or pledgets of gauze soaked in 10% povidone-iodine. Then remove the protective gauze swab and proceed to intestinal anastomosis. In an attempt to limit contamination, some surgeons divide the intestine between two pairs of light crushing clamps (i.e. six clamps in all) and insert the posterior seromuscular layer of sutures before removing the outer clamps and excising the narrow rim of crushed tissue (Fig. 11.10).

6. Perform a single-layer, end-to-end anastomosis, as described in the previous section.

Partial resection

1. A diverticulum on the antimesenteric border may be locally excised. Clamp and cut it off at the neck, then close the defect in two layers as a transverse linear slit. Try to avoid narrowing the intestinal lumen during this procedure.

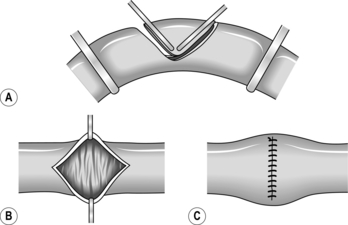

2. A diamond-shaped area of the antimesenteric border may be included in the resection of a localized tumour or wide-mouthed Meckel’s diverticulum. Apply two light crushing clamps (Lang Stevenson’s or Pringle’s) across the antimesenteric border, meeting in a ‘V’ (Fig. 11.11). Incise the bowel flush with the outer aspect of each clamp, and close the wall in two layers, leaving a transverse suture line.

3. A similar defect results if the antimesenteric lesion is excised through a longitudinal ellipse. Approximate the ends of the ellipse, pull apart the sides and close transversely as before.

Checklist

1. Take a last look at the anastomosis. Check that the bowel is pink, that haemostasis is secure and that all mesenteric defects are closed.

2. Remove any ends of suture material that might provoke subsequent adhesions.

3. Replace the intestine and the greater omentum in their normal anatomical position.

4. Aspirate any blood or fluid from the peritoneal cavity using a pool sucker.

5. Drains are usually unnecessary following small bowel anastomoses.

Aftercare

1. Anticipate a period of postoperative paralytic ileus during which maintain the patient on intravenous fluids. Leave the nasogastric tube on free drainage, aspirated regularly for the first 24 hours. Allow water 30 ml/hour by mouth. The tube can usually be removed when the volume of aspirate drops below the volume of fluid taken by mouth.

2. If restoration of oral feeding is delayed for more than a few days, consider parenteral nutrition.

Complications

1. Good surgical technique in limiting contamination from bowel contents reduces the incidence of wound infection. If it does develop, remove sufficient sutures to allow the pus to drain, irrigate the wound, obtain bacteriological cultures and, if cellulitis is present, institute appropriate antibiotic therapy. Once the infection is controlled, the wound usually heals without the need for secondary suture.

2. As with any abdominal operation there is a risk of chest infection resulting from atelectasis. Institute vigorous physiotherapy to avert the need for antibiotics.

3. Occasionally a collection of infected material develops within the abdominal cavity. Abscess sites may be subphrenic, subhepatic, pelvic or adjacent to the anastomosis. The patient develops fever and leukocytosis; localize the collection with ultrasound or CT scans and radiologically place a percutaneous drain.

4. A leaking anastomosis often presents with pain, fever, tachycardia and erythema of the wound or drain site before intestinal contents begin to discharge. The management of an established small-bowel fistula is described later in this chapter.

5. It is occasionally necessary to undertake massive resection of the small bowel, for example when volvulus complicates an obstruction. Repeated enterectomies in Crohn’s disease can similarly remove a substantial percentage of the small intestine. Increased frequency of bowel actions may follow loss of a third to a half of the small bowel, and more extensive resections produce short-bowel syndrome.2 During the initial phase of recovery and adaptation, anticipate and replace losses of fluid and electrolytes, notably potassium. Give codeine or loperamide to control diarrhoea. The body compensates better for proximal than distal enterectomy. After an extensive ileal resection regular injections of vitamin B12 may be needed indefinitely; cholestyramine may diminish the irritative diarrhoea that results from bile-acid malabsorption. A proton pump inhibitor is indicated to reduce gastric acid hypersecretion. Parenteral nutrition will be required in severe short-bowel syndrome.

ENTERIC BYPASS

Appraise

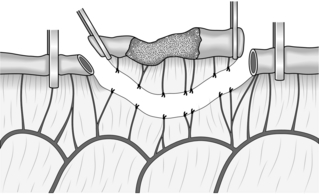

1. Small-bowel loops may become obstructed as a result of carcinomatosis peritonei or particularly dense adhesions, sometimes deep in the pelvis. Irradiated small bowel may fistulate into other organs, such as the bladder or vagina. In these unfavourable circumstances it is often better just to bypass the affected segment of intestine (Fig. 11.12) rather than embark on a difficult and hazardous disentanglement. In radiation enteritis choose overtly normal bowel for the anastomosis, otherwise healing is likely to be impaired.

2. Resection is almost always a better option than bypass in Crohn’s disease of the small bowel. For unresectable carcinoma of the caecum, however, side-to-side bypass is indicated between the terminal ileum and the transverse colon.

Action

Bypass of an unresectable lesion

1. A midline incision is usually appropriate. Aim to anastomose healthy bowel on either side of the diseased segment. Side-to-side anastomosis avoids the risk of closed-loop obstruction developing in a sequestered loop of bowel.

2. Occasionally, if there are multiple sites of actual or imminent obstruction, two or more side-to-side anastomoses between adjacent loops may cause less of a short circuit than one enormous bypass.

3. Approximate a distended loop of proximal intestine to a collapsed loop of distal small bowel (Fig. 11.12) or transverse colon. Pack off the remaining viscera. Consider decompression of the obstructed loops.

4. Carry out a two-layer, side-to-side anastomosis, as previously described. Do not prolong the operation unnecessarily if the patient has advanced disease. A stapled side-to-side anastomosis is appropriate and quick in this situation.

STRICTUREPLASTY

Appraise

1. This technique is virtually confined to patients with Crohn’s disease causing one or more strictures in the small intestine.1,2 It can avoid the need for resection and may therefore be appropriate for patients with disease at several sites or those with recurrent disease and a limited length of residual small bowel.

2. Florid inflammatory change or bowel containing several strictures within a relatively short segment is better treated by local resection. Sometimes you may combine one or more strictureplasties with resection to reduce the total length of bowel excised.

Action

1. Carry a longitudinal full-thickness incision across the stenotic area and for 1 cm into the ‘normal’ bowel on either side.

2. Close the bowel transversely, using either one or two layers of 3/0 Vicryl sutures. Test that the anastomosis is airtight and watertight.

3. This modification of the Heineke-Mikulicz pyloroplasty is suitable for short stenoses. For long stenoses, a modification of the Finney pyloroplasty can be performed, but local resection may be a simpler alternative.

Complications

1. Wound infections are uncommon.

2. Anastomotic leakage may occur, particularly if tight strictures distal to the strictureplasty are not treated.

3. Several studies have reported excellent symptomatic improvement following stricturoplasty. Perioperative complication rates are comparable to standard surgical resection, with low rates of recurrent stricture.

4. It is of concern that small bowel adenocarcinoma has been reported at the site of a previous strictureplasty, so bear this possibility in mind if there is a sudden clinical deterioration.3

REFERENCES

1. Froehlich F, Juillerat P, Mottet C, et al. Obstructive fibrostenotic Crohn’s disease. Digestion 2005;71(1):29–30.

2. Felley C, Vader JP, Juillerat P, et al. Appropriate therapy for fistulizing and fibrostenotic Crohn’s disease: Results of a multidisciplinary expert panel. Journal of Crohns & Colitis 2009;3(4):250–6.

3. Jaskowiak NT, Michelassi F. Adenocarcinoma at a strictureplasty site in Crohn’s disease: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum 2001;44:284–7.

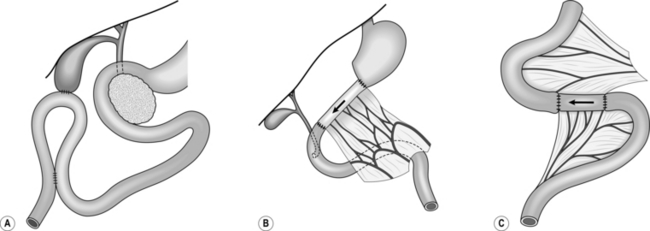

THE ROUX LOOP

Appraise

1. A defunctioned segment of jejunum provides a convenient conduit for connecting various upper abdominal organs to the remaining small bowel. The technique was originally described by the Swiss surgeon Cesar Roux in 1907 for oesophageal bypass.

2. Roux-en-Y anastomosis has two advantages over an intact loop: it can stretch further and it is empty of intestinal contents, thus preventing contamination of the organ to be drained, such as the bile duct. Active peristalsis down the loop encourages this drainage.2

3. Probably the commonest indications for Roux-en-Y anastomosis are biliary drainage in unresectable carcinoma of the pancreatic head and reconstruction after total gastrectomy (Fig. 11.13) or oesophagogastrectomy.

4. Isolated jejunal loops may be interposed between the stomach and duodenum in an isoperistaltic or antiperistaltic direction for different facets of the postgastrectomy syndrome. A reversed loop can be used further downstream in certain cases of intractable diarrhoea (Fig. 11.14).

Action

1. Select a loop of proximal small bowel, beginning 10–15 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz. Hold up the jejunum and trans-illuminate its mesentery to display the precise blood supply, which varies from patient to patient. The number of vessels requiring division depends on the length of conduit required.

2. Starting at the point chosen for intestinal transection, incise the peritoneal leaves of the mesentery in a vertical direction (Fig. 11.15). Divide at least one vascular arcade and the smaller branches that lie between the arcade vessels and the bowel. In laparoscopic cases, a harmonic scalpel may be used to divide the mesentery. Now divide the bowel between clamps.

3. If a longer loop is required, sacrifice two or three main jejunal vessels, preserving an intact blood supply to the extremity of the bowel via the arcades (Fig. 11.15). Individual ligation of the arteries and veins is recommended, using 3/0 vicryl sutures. Check the viability of the bowel at the tip of the loop, and sacrifice the end if it is dusky.

4. Straighten out the efferent limb and take it up by the shortest route for anastomosis to the oesophagus, stomach, bile duct, common hepatic duct or pancreatic duct. It is usually easier to close the end of the limb and fashion a new subterminal opening of the correct diameter. Make a window in the base of the transverse mesocolon, to the right of the duodenojejunal flexure, for passage of the Roux loop. At the end of the operation suture the margins of this defect to the Roux loop to prevent internal herniation.

5. Restore intestinal continuity by uniting the short afferent limb to the base of the long efferent limb, using a sutured end-to-side or stapled side-to-side anastomosis. Ensure that the efferent limb is at least 40 cm long and that the afferent loop is joined to its left-hand side.

ENTEROTOMY

APPRAISE

1. Enterotomy is sometimes needed to extract a foreign body, for example in gallstone ileus or bolus obstruction. After partial gastrectomy, the absence of the antropyloric mill means that whole orange segments or pith, for example, are inadequately broken up and may impact further down the gut. Benign mucosal or submucosal tumours may be explored and removed through an enterotomy incision.

2. Traumatic enterotomy can result from blunt or penetrating abdominal injuries. After a closed injury there is typically a rosette of exposed mucosa on the antimesenteric border of the upper jejunum. After knife or gunshot injuries, look for entry and exit wounds: holes in the small bowel nearly always come in multiples of two.

3. Occasionally, operative enteroscopy may be indicated for unexplained bleeding localized to the small bowel. A paediatric colonoscope or gastroscope can be introduced through a mid-enterotomy and threaded up and down the gut.

Action

Extraction enterotomy

1. It may be possible to knead a foreign body, especially a bolus of food, onwards into the caecum. If so, it will pass spontaneously per rectum. Do not persist with this manoeuvre if it is difficult.

2. Before opening the bowel, pack off the area carefully. Try and manipulate an impacted foreign body upwards for a few centimetres, away from the inflamed segment in which it was lodged.

3. Apply non-crushing clamps across the intestine on either side of the enterotomy site. Open the bowel longitudinally over the foreign body or tumour and gently extract or resect the lesion. Close the bowel transversely in two layers to prevent stenosis.

4. In gallstone ileus examine the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. It is rarely, if ever, appropriate to proceed to cholecystectomy and closure of the biliary-enteric fistula. Examine the rest of the small bowel to exclude a second gallstone.

Traumatic enterotomy

1. Excise devitalized tissue and close the intestinal wound(s) in two layers. Explore an associated haematoma in the mesentery and ligate any bleeding points. Check the viability of the bowel thereafter, and if in doubt resect the damaged segment with end-to-end anastomosis.

2. Examine the other abdominal viscera for concomitant injuries (see Chapter 3).

ENTEROSTOMY

Appraise

1. A feeding jejunostomy permits enteral nutrition in patients who are unable to take sufficient food by mouth.1 Prefer feeding by the enteral route to parenteral nutrition if practicable. Before considering surgical jejunostomy, it may be possible to pass a fine-bore naso-gastric feeding tube through a malignant stricture under endoscopic control.

2. A feeding tube should be placed as high as possible in the jejunum. Even so, troublesome diarrhoea often occurs when feeding is commenced. Some surgeons use a feeding jejunostomy routinely after major oesophagogastric resections. Others reserve it for postoperative complications such as fistula, or serious upper gastrointestinal conditions such as corrosive oesophagogastritis or pancreatic abscess.

3. The ideal feeding jejunostomy is easily inserted, if necessary under local anaesthesia and seals off immediately it is removed. It neither obstructs the bowel nor permits the escape of intestinal contents. It can be placed at laparotomy or laparoscopy via an enterotomy.

4. A terminal ileostomy replaces the anus after total colectomy for malignancy, ulcerative proctocolitis or Crohn’s colitis. The ileostomy may be temporary, if subsequent ileorectal anastomosis is planned or permanent after panproctocolectomy. Improvements in stoma care make ileostomy less of a burden to patients, many of whom are young. It is desirable and usually possible to select and mark the site for ileostomy preoperatively. Choose a point just below waist level and 5 cm to the right of the midline, unless there is a previous scar in this region. It is important to create a spout that will discharge its irritative contents well clear of the skin.

5. Defunctioning loop ileostomy is used to defunction the distal colon after low anterior resection. In comparison with transverse colostomy, it produces predictable volumes of relatively inoffensive faecal effluent and is truly a defunctioning stoma to which an appliance can easily be attached. As a result it has become the temporary stoma of choice. Split ileostomy, with separated stomas, completely defunctions the distal bowel and has been advocated in selected cases of colitis. Split enterostomy has also been advocated to protect a lower enteric anastomosis created in the presence of peritonitis. The distal cut end is either exteriorized as a mucous fistula or oversewn and fixed to the parietal peritoneum to facilitate later retrieval. Kock’s continent ileostomy is now rarely employed: it consists of an ileal reservoir discharging by a short conduit to a flush stoma; a nipple valve is created to preserve continence, and the patient empties the reservoir regularly with a soft catheter. Lastly, a ‘wet’ ileostomy together with an ileal conduit provides one of the commoner methods for achieving urinary diversion.

Action

Feeding jejunostomy

1. Expose the upper jejunum, either laparoscopically or through a small left upper quadrant transverse incision. Trace the bowel proximally to the duodenojejunal flexure. Select a loop 10–20 cm distal to this point, so that it will easily reach the anterior abdominal wall.

2. Insert a Vicryl purse-string suture on the antimesenteric border of the bowel. Make a tiny enterotomy in the centre of the purse-string and introduce a 9Fr feeding jejunostomy tube into the lumen of the bowel (Fig. 11.16). Tighten the purse-string snugly around the tube.

3. To exclude the enterotomy from the peritoneal cavity, suture the bowel to the parietal peritoneum at four points around the entry site of the tube.

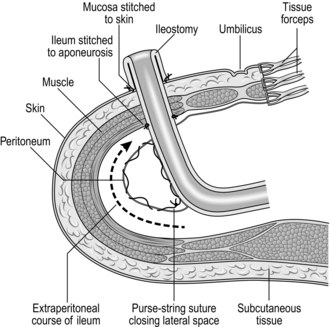

Terminal ileostomy

1. Excise a circular disc of skin and subcutaneous fat, 3 cm in diameter, at the site chosen and marked preoperatively. Make a transverse incision in the exposed anterior rectus sheath, split the fibres of the rectus muscle and open the posterior sheath and peritoneum. The defect should comfortably accommodate two fingers.

2. The terminal ileum will previously have been clamped and transected. Now exteriorize 6–8 cm of bowel, with its mesentery intact, through the circular opening in the abdominal wall, leaving its end securely clamped. Make sure that the mesentery is neither twisted nor tight and that the tip of the ileum remains pink.

3. Some surgeons close the lateral space between the ileostomy and the abdominal wall, using a continuous Vicryl suture (Fig. 11.17). Others tunnel the ileum extraperitoneally. We prefer transperitoneal ileostomy, leaving the lateral space widely open.

4. After closing the main abdominal incision, remove the clamp and trim the crushed portion of ileum. Now suture the edge of the ileum directly to the skin, using Vicryl mounted on a taper-cutting needle. After inserting three or four evenly spaced sutures, the bowel begins to evert spontaneously; if not, use Babcock’s forceps to encourage eversion. Complete the circumferential sutures, producing a spout, which should project about 3 cm from the abdominal wall.

5. Carefully clean and dry the skin around the ileostomy and apply an ileostomy bag at once.

Loop ileostomy

1. Excise a disc of skin and fat and deliver a loop of ileum onto the abdominal wall.

2. Open the bowel, not at the apex of the loop as for a loop colostomy but close to skin level.

3. Suture the mucosa of the distal bowel to the skin. Use Babcock’s forceps to evert the mucosa of the proximal bowel before suture.

4. The completed loop ileostomy looks very like a standard end ileostomy. Attach a suitable appliance, with flange and clip-on bag, to the skin over the stoma.

Aftercare

1. Feeding jejunostomy. Keep the tube patent by introducing 10 ml of water hourly initially. Feed may start at 30 ml per hour on the first postoperative day and be built up incrementally. Consult the dietician about the patient’s individual nutritional needs. Give codeine or loperamide to control diarrhoea. When oral feeding is resumed spigot the tube for 24–48 hours before removal.

2. Ileostomy. Increase oral fluids when the stoma commences to discharge. The effluent will be very loose at first, but will gradually thicken as the ileum adapts. Give bulking agents or antidiarrhoeal drugs as needed. Consult the stomatherapist directly, if he or she has not already seen the patient before operation. Make sure that the patient is competent and confident at managing the stoma before he leaves hospital.

MISCELLANEOUS CONDITIONS

MECKEL’S DIVERTICULUM

1. Potential complications include bleeding, infection, peptic ulceration, perforation, intestinal obstruction or fistulation to the umbilicus. Usually this remnant of the vitello-intestinal duct gives no trouble at all throughout the patient’s life.

2. Incidental Meckel’s diverticulectomy has now been abandoned. A retrospective analysis1 found that the probabilities of producing surgical morbidity and mortality in the adult population were far higher when resecting incidental diverticula.

3. The first step in diverticulectomy is to divide the small vessel that crosses the ileum to supply it. Depending on the size of its mouth, the diverticulum can simply be transected across the neck using a linear stapler or excised with a portion of the antimesenteric border of the bowel. Local resection of the ileum with end-to-end anastomosis may be preferable in a complicated case.

INTUSSUSCEPTION

In infants

1. Ileocolic intussusception usually presents in a child of a few months old with abdominal colic and rectal passage of blood and mucus. Besides confirming the diagnosis, barium enema may reduce the intussusception totally or subtotally. On examination under anaesthetic, if not before, a mass can be felt in the central or upper abdomen with an ‘empty’ right iliac fossa.

2. Open the abdomen through a right Lanz incision and find the sausage-shaped mass. Starting at the apex, squeeze the intussusceptum back along the intussuscipiens as though extracting toothpaste from the bottom of the tube. Do not remove the bowel from the abdominal cavity during this manoeuvre.

3. The final portion of the intussusception is the most difficult to reduce. Deliver the affected segment from the abdomen and gently compress it with a moist swab, before resuming the squeeze. Make certain that reduction is complete before replacing the bowel. No fixation is required, except in the rare event of a recurrent intussusception.

4. If the bowel is clearly gangrenous or the intussusception cannot be reduced, proceed to resection. Usually an end-to-end ileo-ileostomy can be performed.

In adults

1. Intussusception is rare and is nearly always associated with an underlying lesion in the bowel wall such as a benign tumour, metastatic deposit or Meckel’s diverticulum.

2. Reduce the intussusception as far as possible then proceed to local resection of the affected segment of bowel with end-to-end anastomosis.

INTESTINAL ISCHAEMIA

1. The small intestine is supplied by the superior mesenteric (midgut) vessels. Thrombosis may occur on arteriosclerotic plaques at the origin of the superior mesenteric artery, especially if the patient is shocked. The superior mesenteric artery is an uncommon site for peripheral embolism in patients with cardiac arrhythmia or a recent myocardial infarction. Venous gangrene may result if the superior mesenteric or portal veins suddenly undergo thrombosis, for example in extreme dehydration or disseminated intravascular coagulation. Lastly, non-occlusive mesenteric infarction may occur secondary to microcirculatory damage in critically ill patients. Although the diagnosis may be difficult to make, suspect it if unexplained lactic acidosis develops in a postoperative or critically ill patient.

2. Patients with severe mesenteric vascular insufficiency are extremely ill with evidence of peritonitis and shock. Early operation is needed to prevent death.2 At laparotomy, the bowel appears ischaemic or frankly infarcted without evidence of strangulation.

3. Examine the whole intestinal tract and feel for pulsation in all accessible gut arteries. Examine the aorta and its main divisions to determine the extent of atherosclerosis. If the main intestinal vessels and their arcades are patent, the circulation is probably occluded at capillary level.

4. Resect obviously necrotic bowel. Recovery is unlikely if the entire midgut is infarcted following occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery. If an extensive segment is affected, be as conservative as possible to avoid severe short-bowel syndrome. Multiple patches of ischaemia can be oversewn or locally resected.

5. Early cases of arterial embolus or acute in-situ thrombosis may be amenable to revascularization. It is much easier to mobilize the caecum and identify the ileocolic artery than to expose the origin of the superior mesenteric artery itself. Control the vessel with tapes and perform a longitudinal arteriotomy. Pass a Fogarty catheter proximally into the superior mesenteric artery and aorta to dislodge the clot, and try to establish free flow. Rapid injection of heparin saline up the vessel may achieve the same effect. If the bowel regains its normal colour, close the arteriotomy with a venous patch. Otherwise consider side-to-side anastomosis between the ileocolic and right common iliac arteries.

6. Following direct arterial surgery, or in any case in which bowel of doubtful viability has been left in the abdomen, plan to repeat the laparotomy after 24 hours. Further resection of bowel may be clearly indicated at this time.

SMALL-BOWEL FISTULA

1. The spontaneous discharge of bowel contents onto the abdominal wall is a rare event. The vast majority of external fistulas arise either from a leaking anastomosis or from operative injury to the intestine. Impaired healing, radiation enteritis, multiple adhesions, diffuse carcinoma and Crohn’s disease predispose to fistula formation.

2. Do not rush to re-operate once there is an established small-bowel fistula. Correct fluid and electrolyte depletion. Switch to total parenteral nutrition which will reduce the amount of fistula discharge. There is some evidence that Octreotide 150 μg tds may reduce the time for fistulae to heal.3 Consult a stomatherapist on how best to protect the wound and abdominal wall from the effluent, using adhesive seals and collecting bags as appropriate.

3. Obtain an early fistulogram to delineate the leak. A side hole may well close if there is no distal obstruction, but a complete anastomotic dehiscence is almost certain to require re-operation once the patient’s general condition allows.

4. If the patient is toxic, early drainage of an associated abscess may improve the patient’s general health and sometimes allow the fistula to heal. If you encounter a complete dehiscence at this time, it is probably better to exteriorize the bowel ends rather than attempt a repeat anastomosis under unpromising circumstances. This advice may not be appropriate for a high jejunal fistula, however.

5. Do not ordinarily undertake a definitive operation to close a small-bowel fistula if you are an inexperienced surgeon. As a rule resect the damaged portion of bowel. Take care to divide any adhesions that could partially obstruct the distal gut and lead to recurrence of the fistula. Continue nutritional support during the postoperative healing phase.

REFERENCES

1. Peoples J. Incidental Meckel’s diverticulectomy in adults. Surgery 1995;118:649–52

2. Herbert GS, Steele SR. Acute and chronic mesenteric ischemia. Surg Clin North Am 2007;87(5):1115–34.

3. Lloyd DA, Gave SM, Windsor AC. Nutrition and management of enterocutaneous fistula. Br J Surg 2006;93(9):1045–55.

LAPAROSCOPIC APPROACH TO THE SMALL BOWEL

Appraise

1. Diagnostic laparoscopy can be performed with minimal morbidity and can prevent additional complications arising from laparotomy such as wound infection and respiratory complications. In addition to this diagnostic role, laparoscopic surgical techniques can now be applied to most of the therapeutic procedures that were traditionally performed at open surgery and laparoscopic treatment of small bowel complication of Crohn’s disease is now well-established.1

2. Diagnostic laparoscopy is useful in patients with peritonitis or possible small-bowel ischaemia; any subsequent therapeutic procedures being carried out either laparoscopically or via open laparotomy. The small bowel can be examined in detail via the laparoscope. Use a standard infra-umbilical port and a 30°-angled endoscope. Identify the ligament of Treitz initially. Thereafter, by alternately using two atraumatic graspers, expose the entire length of the small bowel to the caecum, dividing any intervening adhesions with laparoscopic scissors. Inspect both the serosal surface and the mesentery.

3. A clinical diagnosis of small-bowel ischaemia is notoriously difficult to make. Laparoscopic examination of the bowel is helpful in determining whether bowel is viable or not. If you are in doubt about the viability of the bowel, make a small incision in order to deliver the suspect segment for closer inspection. Diagnostic laparoscopy is safe and can be performed with minimal morbidity and mortality. It is particularly useful in critically ill patients in whom you wish to avoid unnecessary laparotomy.

4. Small-bowel resection can be performed entirely laparoscopically or with laparoscopic assistance. Determine the segment for resection, dissect the mesentery and divide it using the harmonic scalpel. Perform the subsequent anastomosis intraperitoneally using three firings of a laparoscopic linear stapling device or by standard extracorporeal anastomosis after delivering the bowel to the exterior through a small abdominal incision.

5. Laparoscopic creation of stomas such as loop ileostomy, loop sigmoid colostomy and end colostomy can all be carried out relatively easily. Studies have reported a high success rate in excess of 95%, and a low morbidity rate.

6. Laparoscopic management of acute small-bowel obstruction is theoretically attractive, but may be difficult. Adhesions and distended loops of bowel make establishing pneumoperitoneum hazardous, so an open pneumoperitoneum technique is mandatory and port placement should be under direct vision. If obstruction is due to a single adhesion, this can readily be identified and divided. If adhesions are more extensive, adhesiolysis and relief of obstruction is more difficult. The procedure demands painstaking care, whether performed by the open or the laparoscopic route. Several studies have shown however, that laparoscopy is both effective and safe in patients with small-bowel obstruction. One study in particular2 reported that laparoscopy was effective in a high proportion of patients and that hospital stay was reduced. However, a recent Cochrane systematic review found no randomized or prospective controlled trials comparing laparoscopic with open surgery for small bowel obstruction.3

REFERENCES

1. Dasari BV, McKay D, Gardiner K. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for small bowel Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;1:CD006956.

2. Wullstein C, Gross E. Laparoscopic compared with conventional treatment of acute adhesive small bowel obstruction. Br J Surg 2003;90:1147–1151.

3. Cirocchi R, Abraha I, Farinella E, et al. Laparoscopic versus open surgery in small bowel obstruction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;2:CD007511.

FURTHER READING

Irwin ST, Krukowski ZH, Matheson NA. Single layer anastomosis in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Br J Surg 1990;77:643–644.

Mackey WC, Dineen P. A fifty year experience with Meckel’s diverticulum. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1983;156:56–64.

Michelassi F. Strictureplasty for Crohn’s disease: techniques and long-term results. World J Surg 1998;22:359–363.

Ottinger L. Mesenteric ischaemia. In: Williamson RCN, Cooper MJ, editors. Emergency abdominal surgery. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1990. p. 242–257.

Studley JGN, Williamson RCN. Malignant tumours of the small bowel. In: Taylor TV, Watson A, Williamson RCN, editors. Upper digestive surgery. Oesophagus, stomach and small intestine. London: Saunders; 1999. p. 949–962.

Thomas WEG. Complications of small bowel diverticula. In: Williamson RCN, Cooper MJ, editors. Emergency abdominal surgery. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1990. p. 191–208.

Williams NS, Nasmyth DG, Jones D, et al. De-functioning stomas: a prospective controlled trial comparing loop ileostomy with loop transverse colostomy. Br J Surg 1986;73:566–570.

OPERATIONS FOR OBESITY

Appraise

1. Obesity is becoming more prevalent worldwide, leading to an increasing incidence of related co-morbidities such as type II diabetes, obstructive sleep apnoea, coronary artery disease and stroke. To date, surgery is the only reliable way to produce significant and sustained weight loss and reverse weight-related illnesses.

2. Surgical treatment of obesity can produce significant weight loss and resolve diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and decrease the incidence of malignancy. Furthermore it can improve quality of life and lead to a reduction in medical costs for the health service over the long term.

3. Current UK recommendations allow bariatric surgery for any adult whose body mass index (BMI) is greater than 35 kg/m2 if they have weight-related co-morbidity or a BMI of greater than 40 kg/m2 if they do not.

4. Operations for obesity were originally carried out at laparotomy, but since the late 1990s laparoscopy has become the established method. Open operation is reserved for patients requiring complex revision surgery or for those whose weight precludes pneumoperitoneum.

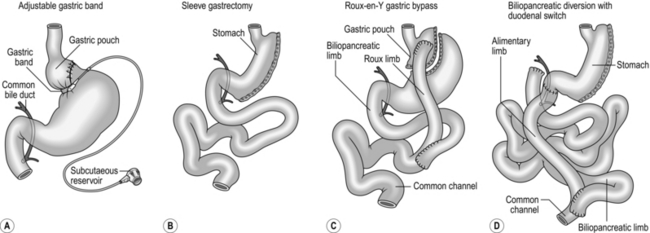

5. The most commonly performed bariatric surgical procedures are the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Other less commonly performed procedures include laparoscopic duodenal switch, open biliopancreatic diversion and vertical banded gastroplasty (Fig. 11.18). We shall discuss the first three of these procedures in detail.

6. Assess patients requiring bariatric (Greek barys = heavy + iatros = physician) surgery within a multidisciplinary team (MDT) before embarking on operation. We recommend involvement of a bariatric surgeon, endocrine physician, psychologist, dietician, bariatric anaesthetist and specialist nurse.

7. Obtain a detailed history to establish the severity of co-morbidities, eating habits and psychological triggers. Only then can you enter into a detailed discussion on which operation is most suitable for the patient. This is influenced by the patient’s weight and BMI, eating habits and the presence of co-morbidities such as diabetes, which responds particularly well to gastric bypass.

8. The decision on choice of procedure ultimately lies with the patient. There are no absolute contraindications to any of the procedures in any patient:

Adjustable gastric band is perceived as the least radical operation, and is wholly reversible so is often favoured by patients with a BMI between 30 and 40 and by younger patients. Because the typical weight loss achieved with gastric banding is of the order of 40–50% of excess weight, patients with an extremely high BMI having gastric bands have little prospect of achieving a final BMI < 30 despite a successful operation, and the higher the initial BMI the more marked is this effect. We recommend that patients with a BMI > 55 consider an alternative to a gastric band.

Adjustable gastric band is perceived as the least radical operation, and is wholly reversible so is often favoured by patients with a BMI between 30 and 40 and by younger patients. Because the typical weight loss achieved with gastric banding is of the order of 40–50% of excess weight, patients with an extremely high BMI having gastric bands have little prospect of achieving a final BMI < 30 despite a successful operation, and the higher the initial BMI the more marked is this effect. We recommend that patients with a BMI > 55 consider an alternative to a gastric band.

Gastric bypass is perceived as very radical and is irreversible.

Gastric bypass is perceived as very radical and is irreversible.

Sleeve gastrectomy lies between the two other operations. With both this procedure and gastric bypass weight loss of the order of 60–70% of excess weight is achievable; thus even patients with a high BMI can achieve a significantly lower final BMI.

Sleeve gastrectomy lies between the two other operations. With both this procedure and gastric bypass weight loss of the order of 60–70% of excess weight is achievable; thus even patients with a high BMI can achieve a significantly lower final BMI.

9. Co-morbidity influences the choice of procedure. The presence of type II diabetes is a clear indication for gastric bypass as resolution of diabetes occurs in approximately 80% of patients and is independent of weight loss. In addition, sleep apnoea, which is dependent on weight loss, is best improved by choosing a procedure which maximizes this. The presence of gastro-oesophageal reflux-disease (GORD) is a relative contraindication to sleeve gastrectomy where symptoms may be exacerbated by removing the fundus of the stomach. Gastric bypass may be impossible in patients with extensive previous abdominal surgery involving the small bowel.

10. Take possible surgical risks into account when planning the operation. Patients with poor cardiovascular reserve who are unlikely to survive re-operation for anastomotic leakage might benefit from gastric banding since the risk of early reoperation is negligible. Also, gastric banding can be abandoned safely and rapidly at any point during the operation if the patient’s condition deteriorates. In contrast, during gastric bypass, once the gastric pouch is created you must complete the operation.

Prepare

1. Equip the surgical unit with an operating table capable of withstanding patient’s excess weight, specialist equipment for moving the anaesthetized patient from table to bed and the necessary laparoscopic stapling devices for the operation proposed. Ensure that the wards are equipped with beds and furniture capable of accommodating larger patients.

2. Fully control any diabetes prior to operation.

3. Commence patients with severe obstructive sleep apnoea on home continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for at least 6 weeks prior to surgery.

4. Restrict carbohydrate diet for 2–3 weeks prior to surgery to reduce the size of the liver. Otherwise the enlarged liver will prejudice surgical exposure of the stomach.

5. Order perioperative prophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin and pneumatic calf compression to minimize the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

LAPAROSCOPIC ADJUSTABLE GASTRIC BAND

Access

1. Has the anaesthetist available a calibration tube? This has an expandable balloon at its tip, which can be passed to lie at the upper extremity of the stomach and inflated. The gastric band can be placed directly below it.

2. Position the patient on a split leg bariatric table, with exaggerated reversed Trendelenburg (head up) attitude. Separate the legs and stand between them.

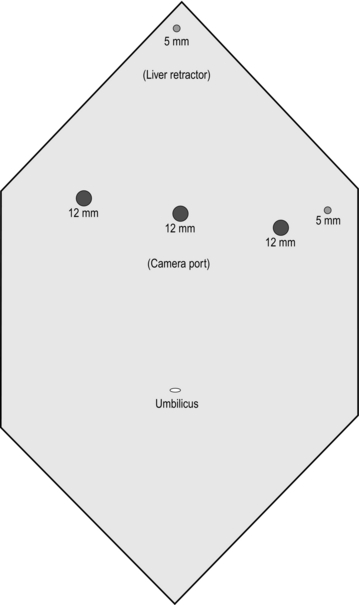

3. Create a pneumoperitoneum using a Veress needle in the midline between the umbilicus and xiphisternum. Once pneumoperitoneum is established, place a 12-mm optical port at the same spot. Now place the remainder of the ports and liver retractor under direct vision (Fig. 11.19).

Action

1. Starting from the angle of His (Wilhelm His 1831–1904, Swiss anatomist), gently free the fundus of the stomach from the left crus of diaphragm using the diathermy hook.

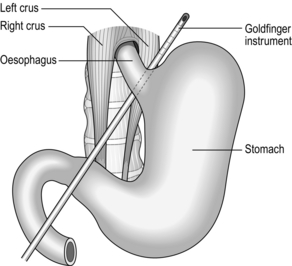

2. Identify the pars flaccida window in the gastro-hepatic omentum and open it gently using the diathermy hook. Incise the peritoneum at the junction between the posterior wall of stomach and the right crus of diaphragm. Through the space which opens here, pass a disposable ‘Goldfinger’ probe behind the stomach to emerge at the angle of His. Angle this so that the tip is clearly visible (Fig. 11.20).

3. Pass the adjustable gastric band into the abdomen via the 15-mm port and hook it onto the tip of the Goldfinger instrument. Now straighten and retract this, pulling the gastric band from left to right behind the stomach into its correct position. Close the band around the stomach, below the 20-ml calibration balloon placed in the uppermost part of the stomach. Take care not to damage the balloon with the atraumatic graspers.

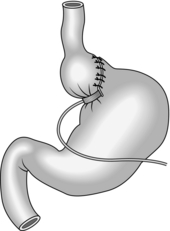

4. Once the band is in position, place three interrupted non-absorbable sutures between the fundus of the stomach and gastric pouch to completely cover the antero-lateral surface of the band. We use 2/0 polyester (Ethibond) sutures for this purpose (Fig. 11.21).

5. Bring the end of the band tubing out of the abdomen via the 15-mm port and connect it to the filling port. Create a small pocket on the surface of the anterior oblique muscle and fix the filling port in this position, ensuring that the rubber diaphragm of the filling port is facing outwards. Close the muscle around the filling tube with a non-absorbable suture.

6. Close Scarpa’s fascia and the skin incisions with absorbable sutures and seal the wounds with skin glue.

Postoperative care

1. Gastric bands may be inserted as a day-case procedure. Oral fluid can be introduced immediately. Patients then progress though pureed food and soft diet until they can manage solid food, in approximately 6–8 weeks.

2. Discharge patients home on daily self-injected low-molecular-weight heparin for 2 weeks as prophylaxis against DVT.

3. Perform the first band inflation 6 weeks after surgery.

4. Long-term successful weight loss following laparoscopic gastric band placement requires a dedicated specialist nurse and dietician to monitor progress and provide close dietary support.

Complications

1. More than 20% of patients may have poor weight loss or regain significant weight after a period of time.

2. Long-term complications such as pouch dilatation, band slippage and band erosion occur rarely but often require removal of the band.

3. A slipped band causing complete obstruction of the gastric pouch is a surgical emergency. Recognize it early if a patient has persistent dysphagia despite deflation of the band. Urgently remove the band surgically to prevent ischaemic necrosis of the gastric wall.

LAPAROSCOPIC SLEEVE GASTRECTOMY

Access

Position the patient similar to that for laparoscopic gastric banding. Ports positions are shown in Figure 11.22.

Action

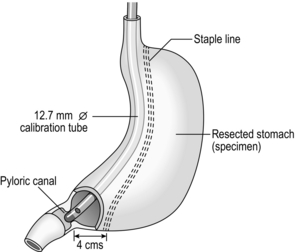

1. Using a harmonic scalpel or Ligasure haemostatic device, start the dissection on the greater curve of stomach approximately one-third of the way from pylorus to the angle of His. Open a window into the lesser sac through the gastro-colic omentum, staying close to the greater curve of stomach. Proceed towards the angle of His achieving control of all the short gastric vessels. Where the tissue is thick, at the gastro-splenic ligament, begin by dividing the anterior leaflet before continuing with the posterior one. Continue dissection until the entire fundus of stomach is mobile, all the way to the angle of His.

2. Return to the starting point of the dissection and separate the gastro-colic omentum from the gastric wall, this time proceeding toward the pylorus (the patient’s right). Stop the dissection approximately 4 cm proximal to the pylorus. The entire greater curve of stomach should now be freely mobile.

3. Advance a 12.7-mm diameter calibration tube from the mouth along the lesser curve of the stomach until it passes through the pylorus. Using a 60-mm linear stapler, starting 4 cm proximal to the pylorus, staple the greater curve snugly to the calibration tube using green (4.1 mm), cartridges. We favour reinforcing each staple line with Peri-strips® which minimize bleeding from the staple line. Continue the staple line snug to the tube all the way to the angle of His (Fig. 11.23).

4. Inspect the staple line carefully and clamp the pylorus with an atraumatic grasper. Using the calibration tube, fill the stomach with methylene blue dye until the stomach tube appears tense. Inspect the staple line for blue dye while slowly withdrawing the tube.

5. Remove the resected stomach in a bag through a 12-mm port site and send it for histological examination.

6. The port sites do not routinely require deep closure. Close the skin with absorbable sutures and skin-glue.

Postoperative

1. Patients can drink water immediately after surgery and free fluids the following day. Provided there is no tachycardia or significant abdominal pain, allow them to go home on the first postoperative day. Instruct patients to follow a 6-week dietary regime identical to that following gastric banding.

2. Discharge patients home on low-molecular-weight heparin for 2 weeks with daily gastric acid suppression therapy for 3 months.

Complications

1. Patients frequently feel severe nausea in the first 24–48 hours after surgery. Manage this by anti-emetics. It always settles spontaneously.

2. Leakage from the gastric staple line occurs in 1–2% of patients. This presents with sudden acute abdominal pain and warrants immediate return to the operating theatre. It is extremely unlikely to occur more than 2 weeks postoperatively.

3. If the patient develops increasing pain with a falling haemoglobin, suspect bleeding from the omentum or spleen. This is usually easy to control by re-laparoscopy and washout of the blood.

LAPAROSCOPIC ROUX-EN-Y GASTRIC BYPASS

Action

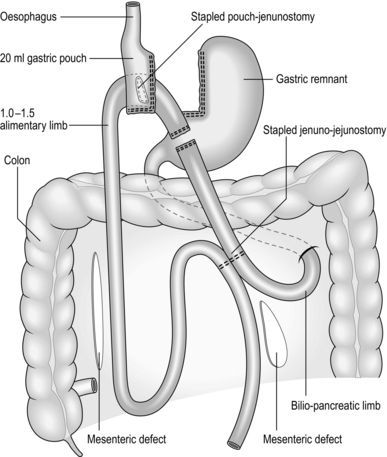

1. Carefully dissect to open up the angle of His. Inflate a 20-cc calibrating balloon in the stomach and retract it until it is stopped by the elastic resistance of the diaphragmatic crura. Start the dissection of the lesser curve just inferior to the balloon. Using the harmonic scalpel, dissect close to the lesser curve posteriorly until the space opens into the lesser sac behind the stomach. After removing the calibration tube, staple horizontally across the medial part of the stomach at this level using the 45-mm linear stapler with blue (3.5 mm staples). Lift the stomach upwards to view the posterior surface of the gastro-oesophageal junction and bluntly dissect to produce a passage through to the left crus of the diaphragm. Using two further cartridges staple vertically upwards towards the left crus to separate the small rectangular pouch of stomach from the main body of the stomach. Open the lower left corner of this pouch with the diathermy hook to produce a passage into the lumen of the pouch.

2. Grasp the greater omentum using atraumatic forceps and lift it superiorly until the transverse colon is suspended horizontally. Starting close to the transverse colon, bisect the omentum vertically until it forms a right and left leaf. Close to the colon extend the dissection to the left and to the right, close to the colonic wall, taking care not to damage the colon. This omental dissection provides a tension-free passage for the jejunum up to the gastric pouch.

3. Lift the colon upwards to expose the mesocolon. Identify the duodeno-jejunal flexure and carefully grasp the proximal jejunum. Draw up a loop of jejunum anterior to the colon until it reaches the pouch without tension. Create a small hole in the anti-mesenteric border of the jejunum and pass the stapling device superiorly into the jejunum. Grasp the pouch on each side of its opening and without force, pass the passive (anvil) blade of the stapler into the pouch until the tissue abuts the angle of the stapler. Fire the stapler (and then ask the anaesthetist to advance the tube until the tip is visible within the pouch. Suture the resultant defect closed with a continuous, absorbable 2/0 mattress suture (Fig. 11.24).

4. Measure 100–150 cm distally along the jejunum from the anastomosis and place a stay suture between the measured jejunum and jejunum midway between the DJF and anastomosis. Using the diathermy hook create adjacent enterotomies close to the stay suture and pass the stapler with a white (2.5 mm) staple cartridge superiorly to join the two bowel lumens. Insert a second straight stapler pointing downwards and fire it, to enlarge the anastomosis lumen. Follow this with a transverse staple firing to close the enterotomy. Insufflate the tube with methylene blue dye under pressure to check both anastomoses for leaks and then divide the short length of jejunum between them with a further white (2.5 mm) staple cartridge.

5. Close the two mesenteric defects created by the anastomoses with a purse string suture of non-absorbable 2/0 Ethibond.

Postoperative

1. Water may be sipped on the first postoperative day with free fluids reintroduced on the second day.

2. If observations are stable patients may be discharged home 2 days after surgery.

3. Patients require prophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin for 2 weeks after discharge and acid suppression therapy for 3 months. The postoperative dietary regime is identical to laparoscopic gastric band insertion, but all patients require vitamin B12 injections 3 monthly and lifelong regular iron, calcium, vitamin D and multivitamin supplements.

Complications

1. If the patient complains of severe pain or develops tachycardia with increased inflammatory markers, consider imaging with CT and oral contrast to assess the anastomosis and exclude significant bleeding. Anastomotic leaks and significant bleeding usually occur within 48 hours of surgery: if you suspect it carry out immediate re-laparoscopy:

Anastomotic stenosis and internal herniation are extremely rare, but suspect them in any patient who re-presents with abdominal symptoms more than 3 months following surgery.

Anastomotic stenosis and internal herniation are extremely rare, but suspect them in any patient who re-presents with abdominal symptoms more than 3 months following surgery.

Make sure the narrow stomach along the lesser curve does not twist during stapling so that the staple line lies laterally along its entire length.

Make sure the narrow stomach along the lesser curve does not twist during stapling so that the staple line lies laterally along its entire length.

Buchwald, H., Avidor, Y., Braunwald, E., et al. A systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA. 2004; 292:1724–1737.

Frachetti, K.J., Goldfine, A.B. Bariatric surgery for diabetes management. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity. 2009; 16:119–124.

O’Brien, P.E., Sawyer, S.M., Laurie, C., et al. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in severely obese adolescents: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010; 303(6):519–526.

Sjöström, L., Gummesson, A., Sjöström, C.D., et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on cancer incidence in obese patients in Sweden (Swedish Obese Subjects Study): a prospective, controlled intervention trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009; 10:653–662.

Sjöström, L., Narbro, K., Sjöström, C.D., et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357:741–752.

Tice, J.A., Karliner, L., Walsh, J., et al. Gastric banding or bypass? A systematic review comparing the two most popular bariatric procedures. Am J Med. 2008; 121:885–893.