Chapter 17 Sleep Medicine

Introduction

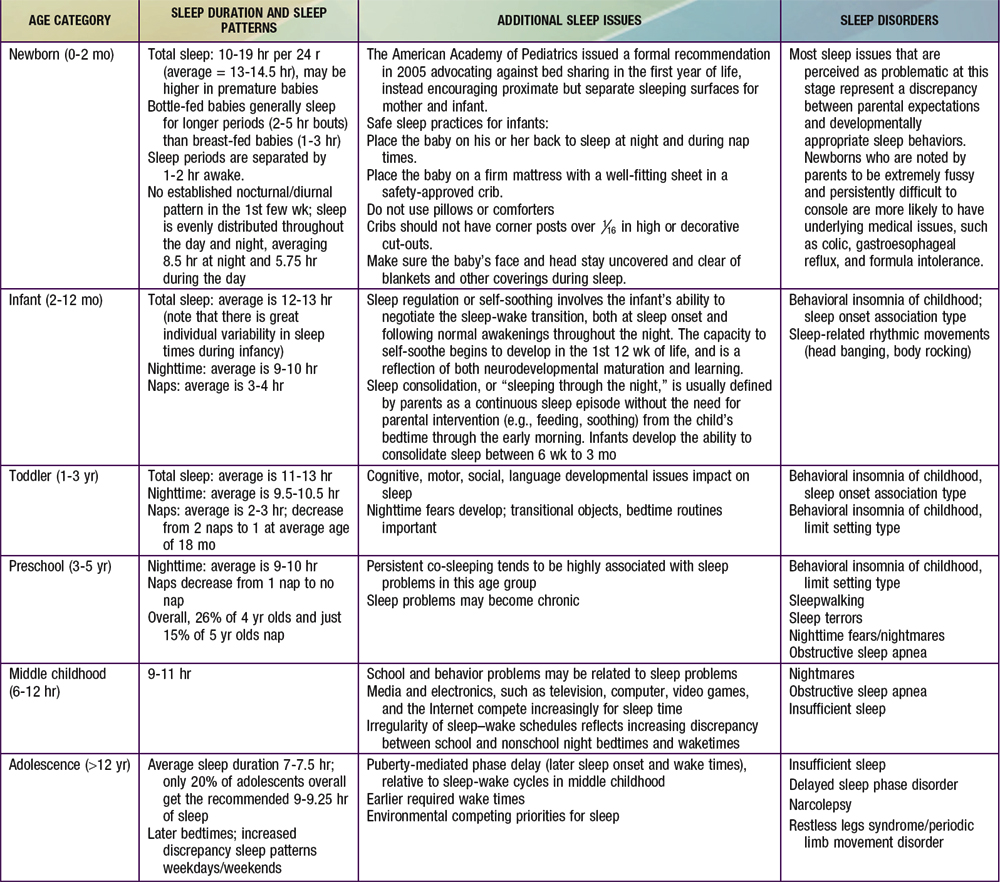

Normal developmental changes in children’s sleep are found in Table 17-1.

Common Sleep Disorders

Insomnia of Childhood

Successful treatment of limit setting sleep disorder generally involves a combination of parent education regarding appropriate limit setting, decreased parental attention for bedtime-delaying behavior, establishment of bedtime routines, and positive reinforcement (sticker charts) for appropriate behavior at bedtime; other behavioral management strategies that have empirical support include bedtime fading (temporarily setting the bedtime closer to the actual sleep onset time and then gradually advancing the bedtime to an earlier target bedtime). Older children may benefit from being taught relaxation techniques to help themselves fall asleep more readily. Following the principles of sleep hygiene for children is essential (Table 17-2).

Table 17-2 BASIC PRINCIPLES OF SLEEP HYGIENE FOR CHILDREN

When the insomnia is not primarily a result of parent behavior or secondary to another sleep disturbance, or to a psychiatric or medical problem, it is referred to as psychophysiologic or primary insomnia, also sometimes called “learned insomnia.” Primary insomnia usually occurs largely in adolescents and is characterized by a combination of learned sleep-preventing associations and heightened physiologic arousal resulting in a complaint of sleeplessness and decreased daytime functioning. A hallmark of primary insomnia is excessive worry about sleep and an exaggerated concern of the potential daytime consequences. The physiologic arousal can be in the form of cognitive hypervigilance, such as “racing” thoughts; in many individuals with insomnia an increased baseline level of arousal is further intensified by this secondary anxiety about sleeplessness. Treatment usually involves educating the adolescent about the principles of sleep hygiene (Table 17-3), institution of a consistent sleep-wake schedule, avoidance of daytime napping, instructions to use the bed for sleep only and to get out of bed if unable to fall asleep (stimulus control), restricting time in bed to the actual time asleep (sleep restriction), addressing maladaptive cognitions about sleep, and teaching relaxation techniques to reduce anxiety. Hypnotic medications are rarely needed.

Table 17-3 BASIC PRINCIPLES OF SLEEP HYGIENE FOR ADOLESCENTS

Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Etiology

In general terms, OSA results from an anatomically or functionally narrowed upper airway; this typically involves some combination of decreased upper airway patency (upper airway obstruction and/or decreased upper airway diameter), increased upper airway collapsibility (reduced pharyngeal muscle tone), and decreased drive to breathe in the face of reduced upper airway patency (reduced central ventilatory drive) (Table 17-4). Upper airway obstruction varies in degree and level (i.e., nose, nasopharynx/oropharynx, hypopharynx) and is most commonly due to adenotonsillar hypertrophy, although tonsillar size does not necessarily correlate with degree of obstruction, especially in older children. Other causes of airway obstruction include allergies associated with chronic rhinitis/nasal obstruction; craniofacial abnormalities, including hypoplasia/displacement of the maxilla and mandible; gastroesophageal reflux with resulting pharyngeal reactive edema; nasal septal deviation; and velopharyngeal flap cleft palate repair. Reduced upper airway tone may result from neuromuscular diseases, including hypotonic cerebral palsy and muscular dystrophies, or hypothyroidism. Reduced central ventilatory drive may be present in some children with Arnold-Chiari malformation and meningomyelocele. In other situations, the etiology is mixed; individuals with Down syndrome, by virtue of their facial anatomy, hypotonia, macroglossia, and central adiposity, as well as the increased incidence of hypothyroidism, are at particularly high risk for OSA, with some estimates of as great as 70% prevalence.

Table 17-4 ANATOMIC FACTORS THAT PREDISPOSE TO OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA AND HYPOVENTILATION IN CHILDREN

NOSE

NASOPHARYNGEAL AND OROPHARYNGEAL

CRANIOFACIAL

Clinical Manifestations

One of the most important but frequently overlooked sequelae of OSA in children is the effect on mood, behavior, learning, and academic functioning. The neurobehavioral consequences of OSA in children include daytime sleepiness with drowsiness, difficulty in morning waking, and unplanned napping or dozing off during activities, although evidence of frank hypersomnolence tends to be less common in children compared to adults with OSA. Mood changes include increased irritability, mood instability and emotional dysregulation, low frustration tolerance, and depression/anxiety. Behavioral issues include both “internalizing” (i.e., increased somatic complaints and social withdrawal) and “externalizing” behaviors, including aggression, impulsivity, hyperactivity, oppositional behavior, and conduct problems. There is a substantial overlap between the clinical impairments associated with OSA and the diagnostic criteria for ADHD, including inattention, poor concentration, and distractibility (Chapter 30). There also appears to be a selective impact of OSA specifically on “executive functions,” which include cognitive flexibility, task initiation, self-monitoring, planning, organization, and self-regulation of affect and arousal; executive function deficits are also a hallmark of ADHD.

Diagnosis

The American Academy of Pediatrics clinical practice guidelines provide excellent information for the evaluation and management of uncomplicated childhood OSA (Table 17-5). There are no physical examination findings that are truly pathognomonic for OSA, and most healthy children with OSA appear normal; certain physical examination findings may suggest OSA. Growth parameters may be abnormal (obesity or, less commonly, failure to thrive), and there may be evidence of chronic nasal obstruction (hyponasal speech, mouth breathing, septal deviation, “adenoidal facies”), as well as signs of atopic disease (i.e., “allergic shiners”). Oropharyngeal examination may reveal enlarged tonsils, excess soft tissue in the posterior pharynx, and a narrowed posterior pharyngeal space. Any abnormalities of the facial structure, such as retrognathia and/or micrognathia, midfacial hypoplasia, best appreciated by inspection of the lateral facial profile, increase the likelihood of OSA and should be noted. In very severe cases, there may be evidence of pulmonary hypertension, right-sided heart failure, and cor pulmonale; systemic hypertension, unlike in adults, is relatively uncommon.

Table 17-5 AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA SYNDROME (APRIL 2002)

All children should be screened for snoring.

Complex high-risk patients should be referred to a specialist.

Patients with cardiorespiratory failure cannot await elective evaluation.

Diagnostic evaluation is useful in discriminating between primary snoring and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, the gold standard being polysomnography.

Adenotonsillectomy is the first line of treatment for most children, and continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is an option for those who are not candidates for surgery or do not respond to surgery.

High-risk patients should be monitored as inpatients postoperatively.

Patients should be re-evaluated postoperatively to determine whether additional treatment is required.

Parasomnias

Etiology

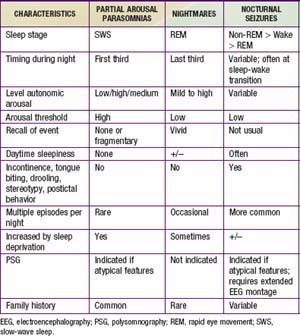

Partial arousal parasomnias, which include sleepwalking, sleep terrors, and confusional arousals are more common in preschool and school-aged children because of the relatively higher percentage of SWS in younger children. Any factor that is associated with an increase in the relative percentage of SWS (certain medications, previous sleep deprivation) may increase the frequency of events in a predisposed child. There appears to be a genetic predisposition for both sleepwalking and night terrors. In contrast, nightmares, which are much more common than the partial arousal parasomnias but are often confused with them, are concentrated in the last third of the night, when REM sleep is most prominent. Partial arousal parasomnias may also be difficult to distinguish from nocturnal seizures. Table 17-6 summarizes similarities and differences among these nocturnal arousal events.

Sleep-Related Movement Disorders: Restless Legs Syndrome/Periodic Limb Movement Disorder and Rhythmic Movements

Health Supervision

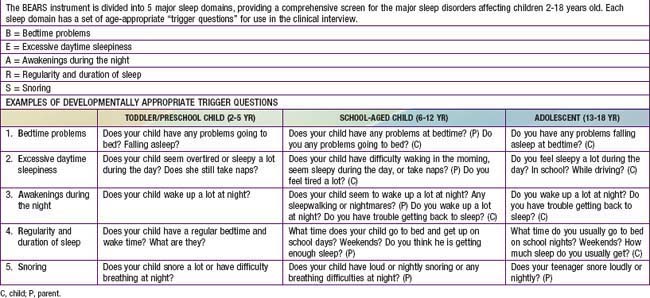

It is especially important for pediatricians to both screen for and recognize sleep disorders in children and adolescents during health encounters. The well child visit is an opportunity to educate parents about normal sleep in children and to teach strategies to prevent sleep problems from developing (primary prevention) or from becoming chronic, if problems already exist (secondary prevention). Developmentally appropriate screening for sleep disturbances should take place in the context of every well child visit and should include a range of potential sleep problems; one simple sleep screening algorithm, the “BEARS,” is outlined in Table 17-7. Because parents may not always be aware of sleep problems, especially in older children and adolescents, it is also important to question the child directly about sleep concerns. The recognition and evaluation of sleep problems in children requires both an understanding of the association between sleep disturbances and daytime consequences, such as irritability, inattention, and poor impulse control, and familiarity with the developmentally appropriate differential diagnoses of common presenting sleep complaints (difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep, episodic nocturnal events). An assessment of sleep patterns and possible sleep problems should be part of the initial evaluation of every child presenting with behavioral and/or academic problems, especially ADHD.

Bradley TD, Floras JS. Obstructive sleep apnoea and its cardiovascular consequences. Lancet. 2009;373:82-90.

Capdevila OS, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Dayyat E, et al. Pediatric obstructive sleep apnea: complications, management, and long-term outcomes. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:274-282.

Gozal D, Kheirandish-Gozal L. Neurocognitive and behavioral morbidity in children with sleep disorders. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2007;13:505-509.

Guilleminault C, Quo S, Huynh NT, et al. Orthodontic expansion treatment and adenotonsillectomy in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in prepubertal children. Sleep. 2008;31:953-957.

Horsley T, Clifford T, Barrowman N, et al. Benefits and harms associated with the practice of bed sharing: a systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:237-245.

Ivanenko A, editor. Sleep and psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents. New York: Informa Healthcare, 2008.

Jenni OG, Carskadon MA. Sleep behavior and sleep regulation from infancy through adolescence: normative aspects. Sleep Med Clin. 2007;2:321-329.

Khatwa U, Kothare SV. Restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements disorder in the pediatric population. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2010;16:559-567.

Kothare S, Kaleyias J. Narcolepsy and other hypersomnias in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:666-675.

Loughlin GM. Primary snoring in children—no longer benign. J Pediatr. 2009;155:306-307.

Mayer G, Wilde-Frenz J, Kurella B. Sleep related rhythmic movement disorder revisited. J Sleep Res. 2007;16:110-116.

Mindell J, Owens J. A clinical guide to pediatric sleep: diagnosis and management of sleep problems in children and adolescents. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

Morgenthaler TI, Owens J, Alessi C, et al. Practice parameters for behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Sleep. 2006;29:1277-1281.

Owens J. Socio-cultural considerations and sleep practices in the pediatric population. Sleep and disorders of sleep in women. Driver H, editor. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 3, 2008;97-107.

Petit D, Touchette E, Tremblay RE, et al. Dyssomnias and parasomnias in early childhood. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1016-1025.

Picchietti D, Allen RP, Walters AS, et al. Restless legs syndrome: prevalence and impact in children and adolescents—the Peds REST study. Pediatrics. 2007;120:253-266.

Picchietti MA, Picchietti DL. Advances in pediatric restless legs syndrome: iron, genetics, diagnosis and treatment. Sleep Med. 2010;11:643-651.

Section on Pediatric Pulmonology, Subcommittee on Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome, American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline: diagnosis and management of childhood obstructive sleep apnea. Pediatrics. 2002;109:704-712.

Sheldon SH, Ferber R, Kryger MH, editors. Principles and practices of pediatric sleep medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2005.

Simard V, Nielsen TA, Tremblay RE, et al. Longitudinal study of preschool sleep disturbance. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:360-367.

Stores G. Aspects of parasomnias in children and adolescence. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:63-69.

Touchette E, Mongrain V, Petit D, et al. Development of sleep-wake schedules during childhood and relationship with sleep duration. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:343-349.

Wiggs L. Behavioural aspects of children’s sleep. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:59-62.

Yang Q, Li L, Yang R, et al. Family-based and population-based association studies validate PTPRD as a risk factor for restless legs syndrome. Movement Disorders. 24 Jan 2011. DOI: 10.1002/mds.23459