Chapter 18 Sleep Laboratory Diagnosis of Restless Legs Syndrome

As stated previously in this book, the diagnosis of restless legs syndrome (RLS) relies essentially on the presence of four clinical manifestations: (1) an urge to move, usually accompanied or caused by uncomfortable and unpleasant sensations in the legs, (2) the urge to move or unpleasant sensations beginning or worsening during periods of rest or inactivity, (3) the urge to move or unpleasant sensations partially or totally relieved by movement, and (4) the urge to move or unpleasant sensations worse in the evening or night than during the day, or occur only in the evening or night.1 Other clinical features, such as a positive family history or a positive therapeutic response to dopaminergic agents, are supportive criteria that are not essential for the diagnosis of RLS but can be helpful, especially in cases of diagnostic uncertainty.

Despite the efforts of international experts of RLS to establish standard criteria,1,2 the clinical diagnosis of this condition remains, in several patients, difficult to make on the basis of the clinical evaluation solely. Thus, several attempts have been made to develop objective methods for diagnosing RLS. This includes both polysomnography (PSG) and the suggested immobilization test (SIT).

Diagnostic Polysomnography

Periodic Leg Movements in Sleep

PLMS are best described as rhythmic extensions of the big toe and dorsiflexions of the ankle with occasional flexions of the knee and hip. The movements may occur in one or, more typically, both legs simultaneously. The quantification of PLMS is routinely performed in the sleep laboratory by the recording of bilateral anterior tibialis muscle surface EMG. According to standard criteria originally developed by Coleman3 and later revised by a task force of the American Sleep Disorders Association,4 PLMS are scored only if they are part of a series of four or more consecutive movements lasting 0.5 to 5 seconds and if they are separated by intervals of 5 to 90 seconds. Different amplitude criteria were being used to score PLMS. In most laboratories, PLMS are scored only if they have an amplitude of one quarter or more of the EMG potential recorded at the time of foot or toe dorsiflexion during calibration of the PSG equipment before the nocturnal sleep recording. However, this criterion is not universally applied, and in several studies no amplitude criterion is being used. A new criterion is based on elevation above baseline.5 Traditionally, an index (number of movements per hour of sleep) of PLMS greater than 5 for the entire night has been regarded as pathological,3,4 regardless of the patient’s age or sleep complaint. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders stated that the PLMS index must be interpreted in the context of the patient’s sleep complaint, emphasizing the importance of clinical context over an absolute cutoff value.6 In addition, they suggest that a cutoff value of 15 may be more appropriate for most adult cases. However, these recommendations need to be further validated.

Sensitivity of the Periodic Leg Movements in Sleep Index in the Diagnosis of Restless Legs Syndrome

In 1965, Lugaresi and coworkers7 first reported the presence of PLMS (originally called nocturnal myoclonus) in patients with RLS. Subsequently, the study of 131 patients with RLS using Coleman’s scoring criteria showed that approximately 80% of them were found to have a PLMS index of greater than 5.8 In this study, a subgroup of 49 patients were recorded for two consecutive nights. On each night, 82% of the patients had a PLMS index greater than 5, and 76% met this criterion on both nights. However, when the highest number of PLMS for the two nights was considered for each patient, 87.8% was found to meet this criterion. When a PLMS index of greater than 10 was used as the criterion, 67.3% of patients met it on the first night, whereas 81.6% of patients met it when the worst of two nights was considered.8 A significant positive correlation (Pearson r = 0.66; p >.001) was found between PLMS indices for nights 1 and 2. More recently, Sforza and coworkers9 confirmed these results in their study of 68 patients with RLS and showed that the PLMS index of the patients (as a group) did not significantly change across two nights of PSG with a good night-to-night reproducibility. However, they found a significant intra-individual difference in the correlation coefficient for the PLMS index (r = 0.54, p =.003). The individual internight changes in PLMS index appeared independent of age, International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) severity score, duration of the disease, and changes in sleep parameters. These results demonstrate the diagnostic interest of repeating nocturnal PSG recordings in RLS patients.

Specificity of the Periodic Leg Movements in Sleep Index: Restless Legs Syndrome Patients Versus Normal Control Subjects

The specificity of PLMS as a diagnostic tool for RLS varies considerably with age. Indeed, a high PLMS index is rather uncommon in normal children and young adults.10 The mean PLMS index increases dramatically in healthy middle-aged individuals10–16 with and without sleep complaint. For example, in a study of 70 middle-aged subjects (mean age, 40 to 60 years) without sleep complaint, the mean PLMS index was 9.6, but 27 individuals (38%) had a PLMS index greater than 5 and 22 (31%) had a PLMS index greater than 10. The mean PLMS index further increases with advancing age; the mean PLMS index was higher than 20 in healthy subjects after the age of 50.10 Age also influenced the periodicity of PLMS in healthy controls. Interval histograms of PLMS performed in different age groups showed that PLMS are not clearly periodic in healthy subjects before the age of 40 years.

One study17 assessed the sensitivity and the specificity of the PLMS index in discriminating 100 RLS patients (with a mean age of 48.8 years) from 50 gender- and age-matched healthy control subjects (with a mean age of 48.4 years). Analyses revealed that a PLMS index of 7 best discriminated between RLS patients and control subjects with a sensitivity and a specificity of 78% and 76%, respectively. The results were obtained in middle-aged individuals, but considering the marked differences in PLMS index across age groups in healthy controls, these specificity measures are expected to be much higher in children and considerably lower in the elderly.

Specificity of the Periodic Leg Movements in Sleep Index: Restless Legs Syndrome Versus Other Sleep Disorders

PLMS also occurs in a wide range of sleep disorders18,19 including narcolepsy,19–21 REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD),18,22 obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS),23–25 insomnia,18,19 and hypersomnia.18,19 Indeed, a PLMS index greater than 5 was found in 68% of 170 narcoleptic patients recorded in our laboratory.26 In a study of 40 RBD patients, 32 (80%) showed a PLMS index greater than 5 and 28 (70%) showed an index greater than 10.22 PLMS were also reported frequently in patients with OSAS. In this condition, leg movements may occur at the end of the apnea in association with an arousal response. Patients with OSAS also have PLMS independent of apnea episodes. In one study,24 leg movements with long intermovement intervals were found to be associated with respiratory events, whereas those with short intervals were identified as PLMS independent of respiration. It should be noted that, in OSAS patients, the PLMS index usually decreases with successful treatment of OSAS with nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), although in a large number of patients it remains elevated after CPAP treatment.24,25 The prevalence and characteristics of leg movements in OSAS, their relation with respiratory events, and their response to treatment remain to be elucidated.

PLMS were also reported in patients with insomnia or hypersomnia. In the absence of any other cause, insomnia or hypersomnia with PLMS is referred to as periodic leg movements disorder (PLMD). Several researchers and clinicians have questioned the status of PLMD as a specific clinical entity. Although PLMS do occur in insomnia and hypersomnia, their prevalence in people with these disorders is often the same as in groups of age-matched control subjects who report no disturbance of sleep or vigilance. Furthermore, the relationship between PLMS, sleep quality, and daytime sleepiness is still unclear in these clinical populations. Although some reports had indicated an association between the PLMS index and PSG sleep parameters27–31 or subjective sleep variables,16,32 most studies suggested that the PLMS is not related to subjective sleepiness, sleep complaints, or PSG parameters in patients with insomnia or hypersomnia.16,33–37

Periodic Arm Movements

Almost 50% of patients with RLS also report sensory symptoms in the arms.19,38 PSG recordings, including extensor digitorum communis EMG, revealed the presence of PAM during wakefulness in approximately two thirds of these patients, but only a small number of patients with a complaint of arm paresthesia show PAM during sleep (3 of 22 [13.8%]).39 Therefore, the recording of PAM during sleep has little diagnostic value in RLS. On the other hand, the sensitivity and specificity of PAM during wakefulness in patients with arm symptoms remain to be established.

Periodic Leg Movements in Sleep–Arousal Index

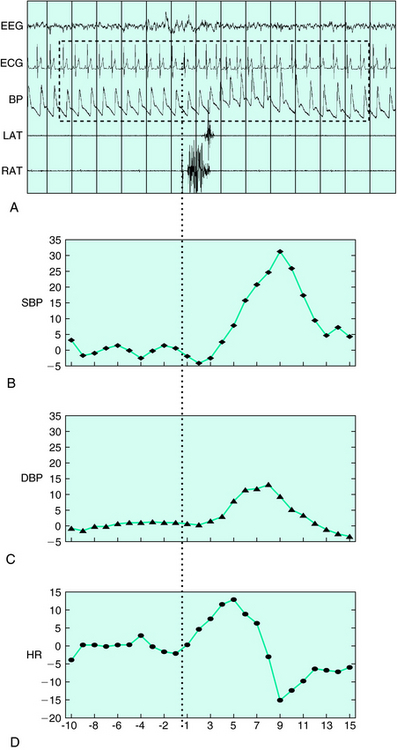

PLMS are often associated with EEG signs of arousals (Fig. 18-1). These arousals may be of short duration, insufficient for scoring an epoch as wakefulness, and are therefore named EEG arousals or micro-arousals. The American Sleep Disorders Association40 provided rules to score these EEG arousals. In NREM sleep, EEG arousals are defined as a return to alpha, theta, or beta activity lasting between 3 and 15 seconds. They must be well differentiated from background EEG activity. In REM sleep, criteria include, in addition to EEG changes, an increase in chin EMG amplitude. Using these criteria, approximately one third of PLMS seen in patients with RLS were associated with EEG arousals.41 Major differences can be found in the literature regarding the percentage of PLMS associated with EEG arousals. This discrepancy may result from different definitions of EEG arousals but also from the low inter-rater reliability encountered with EEG arousals scoring.42

The sensitivity and the specificity of the PLMS–arousal index were assessed in 100 idiopathic RLS patients and 50 healthy control subjects.17 Although relatively specific (specificity of 84%), the PLMS–arousal index showed a low sensitivity of 60% and was therefore not recommended for diagnosing RLS. Several methods may be used to increase the sensitivity of the PLMS–arousal index. For example, one may use EEG spectral analysis rather than visual detection to score EEG arousals. Another possibility would be to look at other measures of physiologic activation. Recently, more attention has been paid to autonomic activation associated with PLMS. Regardless of the presence of EEG arousal, PLMS are associated with a tachycardia lasting 5 to 10 heartbeats after the onset of the movement and is followed by a bradycardia of similar duration41,43,44 (see Fig. 18-1A, D). This cardiac response associated with PLMS was much lower in PLMS found in narcolepsy or in RBD patients compared with that in patients with RLS.22,45 Blood pressure (BP) increases were found in association with all PLMS (see Fig. 18-1A–C). On average, systolic BP increased by 22 mm Hg and diastolic BP by 12 mm Hg (unpublished data). BP changes were greater when PLMS were associated with EEG signs of arousal. The magnitude of the BP augmentations, as much as 40 mm Hg in some individuals, strongly suggests that PLMS, especially in older subjects can be harmful to the cardiovascular system. The value of these autonomic markers in diagnosing RLS remains to be further assessed.

Periodic Leg Movements While Awake During Nocturnal Polysomnography

In patients with RLS, PSG recordings often reveal the presence of PLMW. Although no standard criteria have been defined yet to score these so-called PSG–PLMW, most studies used the same criteria as for PLMS, except for the duration criterion, which has been changed to span 0.5 to 10 seconds,17 according to the scoring criteria developed for PLMW during the SIT.47 In one study, the PLMW index (number of PLMs per hour of wakefulness during the night, starting at lights off and finishing at lights on) was found to be even more sensitive (87%) and specific (80%) than the PLMS index to discriminate RLS patients from healthy control subjects.17 However, these results were obtained in middle-aged individuals only. One study10 showed that PLMW are quite common in healthy children and young adults. PLMW index was lower in middle-aged subjects but increased again in older subjects. This may limit the usefulness of PLMW in the diagnosis of RLS in younger patients. The specificity of the PLMW index will also need to be assessed in patients with other sleep disorders and especially insomnia, because insomniacs often complain of tossing and turning in bed while trying to return to sleep. Contrary to what is seen in RLS,46 intermovement interval histograms revealed that the PLMW are not periodic in healthy subjects of any age group.10 An intense motor activity was seen in young healthy subjects when they are awake at night. Because they are numerous, several of these movements meet the scoring criteria for PLMW (duration of 0.5 to 10 seconds and separation by intervals of 5 to 90 seconds) even though they are not truly periodic. One way of increasing the specificity of the PLMW index in diagnosing RLS in young individuals would be to use more stringent criteria in the assessment of the periodicity.

The Suggested Immobilization Test

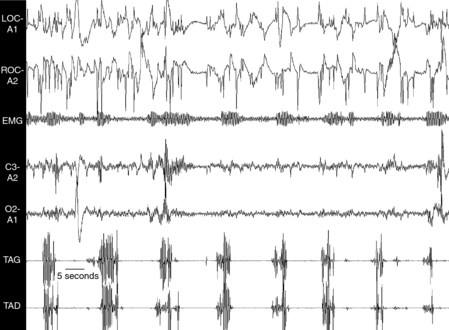

Because RLS symptoms are primarily observed during wakefulness, especially when the patient is at rest in the evening and/or during the night, a test was designed during which sensory and motor symptoms of RLS are quantified during a period of immobility taking place in the evening before the PSG recording. The test was called the SIT.17,47,48 During this test, the patient remains in bed, reclined at a 45-degree angle with the legs outstretched and eyes open. They are instructed to avoid moving voluntarily for the entire duration of the test, which is designed to last 1 hour. A study suggested that it is essential to administer the test after 9:00 P.M. because RLS symptoms, according to their circadian variation, peak around 1:00 A.M.,49 and are more severe and sensitive to immobility at that time.50 Surface EMG studies from right and left anterior tibialis muscles are used to quantify leg movements. Criteria used to score these so-called SIT-PLMW are the same as for PSG-PLMW.48 Figure 18-2 shows a sample of EMG recording of PLMW during the SIT. Although most movements are of short duration, a significant number of movements (17%) last between 5 and 10 seconds, supporting the modification in the scoring criteria of PLMW.47 The SIT-PLMW index represents the total number of PLMs recorded during the 1-hour SIT procedure. In some patients, however, it is necessary to interrupt the SIT before 1 hour due to severe sensory symptoms. In this case, the index is calculated by dividing the total number of PLMW by the duration of the SIT in minutes and multiplying by 60. In addition to the EMG recording of PLMW, the patient has to estimate his or her level of leg discomfort on a 100-mm horizontal visual analogue scale. The descriptors “no discomfort” and “extreme discomfort” are used at the left and right end points of the scale, respectively. Twelve values are obtained (every 5 minutes for the 1-hour SIT). The mean leg discomfort score (MDS) represents the average value of these 12 measures. As seen in Figure 18-3, both the PLMW and the leg discomfort score progressively increase during the SIT, with the PLMW reaching a plateau after about 35 minutes of immobility.

The sensitivity and specificity of the SIT were assessed in a clinical population of 100 patients with RLS and in 50 age-matched normal control subjects16 (Fig. 18-4). In this study, a SIT-PLMW index of 12 was found to correctly classify only 69.3% of patients with RLS and control subjects (sensitivity of 62% and specificity of 84%). This low sensitivity may be explained by the instructions given to the patient before the test. Indeed, when the instruction is “to try not to move” during the SIT, several patients are able to restrain themselves from moving although they experience high levels of discomfort in their legs. Thus, it would be interesting to test whether different instructions given to the patients can modify the sensitivity of the SIT-PLMW index. The same study also showed that a MDS of 11 highly discriminated RLS patients from healthy control subjects, with a sensitivity of 82% and a specificity of 84%. Two studies confirmed the results obtained with the SIT as well as its diagnostic value. In 2004, Garcia-Borreguero and coworkers51 studied 30 patients with idiopathic RLS and found a significant correlation between the severity scale developed by the International RLS Study Group51 and the SIT-PLMW index. Birinyi and coworkers52 studied 28 patients with idiopathic RLS and 18 control subjects. As found earlier by Michaud and colleagues,53 there is a progressive increase in the PLMW during the SIT. They also looked at the sensory events by asking the patient to indicate each time an unpleasant leg sensation is experienced. Using these markers, they found that 38% of PLMW were associated with sensory events. These results are slightly lower than the 49% previously reported by Pelletier and coworkers55 in a former version of the SIT called the forced immobilization test, in which the legs of the patients were forced to immobility by a restrictive device. None of these studies52,53 used the exact method originally described by Michaud and coworkers54 for the quantification of leg discomfort during the SIT.

1. Allen R, Picchietti D, Hening WA, et al. Restless legs syndrome: Diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the Restless Legs Syndrome Diagnosis and Epidemiology Workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003;4:101-119.

2. Walters AS, Group Organizer and Correspondent for the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Toward a better definition of the restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 1995;10:634-642.

3. Coleman RM. Periodic movements in sleep (nocturnal myoclonus) and restless legs syndrome. In: Guilleminault C, editor. Sleeping and Waking Disorders: Indications and Techniques. Menlo Park, CA: Addison- Wesley; 1982:265-295.

4. Atlas Task Force of the American Sleep Disorders Association. Recording and scoring leg movements. Sleep. 2003;16:748.

5. Zucconi M, Ferri R, Allen R, et al. The official World Association of Sleep Medicine (WASM) standards for recording and scoring periodic leg movements in sleep (PLMS) and wakefulness (PLMW) developed in collaboration with a task force from the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG). Sleep Med. 2006;7:175-183.

6. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. Diagnostic and Coding Manual, ed 2. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2005.

7. Lugaresi E, Tassinari CA, Coccagna G, Ambrosetto C. Particularités cliniques et polygraphiques du syndrome d’impatiences des membres inférieurs. Rev Neurol. 1965;113:545-555.

8. Montplaisir J, Boucher S, Poirier G, et al. Clinical polysomnographic and genetic characteristics of restless legs syndrome: A study of 133 patients diagnosed with new standard criteria. Mov Disord. 1996;12:61-65.

9. Sforza E, Haba-Rubio J. Night-to-night variability in periodic leg movements in patients with restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2005;6:259-267.

10. Pennestri MH, Whittom S, Adam B, et al. PLMS and PLMW in healthy subjects as a function of age: prevalence and interval distribution. Sleep. 2006;29:1183-1187.

11. Carrier J, Frenette S, Montplaisir J, et al. Effects of periodic leg movements during sleep in middle-aged subjects without sleep complaints. Mov Disord. 2005;20:1127-1132.

12. Ancoli-Israël S, Kripke DF, Mason W, et al. Sleep apnea and periodic movements in sleep in an aging population. J Gerontol. 1985;40:419-425.

13. Ancoli-Israel S, Kripke DF, Klauber MR, et al. Periodic limb movements in sleep in community-dwelling elderly. Sleep. 1991;14:496-500.

14. Dickel MJ, Mosko SS. Morbidity cut-offs for sleep apnea and periodic leg movements in predicting subjective complaints in seniors. Sleep. 1990;13:155-166.

15. Hornyak M, Riemann D, Voderholzer U. Do periodic leg movements influence patients’ perception of sleep quality? Sleep Med. 2004;5:597-600.

16. Mosko SS, Dickel MJ, Paul T, et al. Sleep apnea and sleep-related periodic leg movements in community resident seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36:502-508.

17. Michaud M, Paquet J, Lavigne G, et al. Sleep laboratory diagnosis of restless legs syndrome. Eur Neurol. 2002;48:108-113.

18. Coleman RM, Pollak CP, Weitzman ED. Periodic movements in sleep (nocturnal myoclonus): Relation to sleep disorders. Ann Neurol. 1980;8:416-421.

19. Montplaisir J, Michaud M, Denesle R, Gosselin A. Periodic leg movements are not more prevalent in insomnia or hypersomnia but are specifically associated with sleep disorders involving a dopaminergic impairment. Sleep Med. 2000;1:163-167.

20. Dauvilliers Y, Billiard M, Montplaisir J. Clinical aspects and pathophysiology of narcolepsy. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114:2000-2017.

21. Montplaisir JY, Whittom S, Rompré S, et al. Prevalence and functional significance of periodic leg movements in narcolepsy [abstract]. Sleep. 2005;28(suppl):A222.

22. Fantini L, Michaud M, Gosselin N, et al. Periodic leg movements in REM sleep behavior disorder and related autonomic and EEG activation. Neurology. 2002;59:1889-1894.

23. Fry JM, DiPhillipo MA, Pressman MR. Periodic leg movements in sleep following treatment of obstructive sleep apnea with nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Chest. 1989;96:89-91.

24. Carelli G, Krieger J, Calvi-Gries F, Macher JP. Periodic limb movements and obstructive sleep apneas before and after continuous positive airway pressure treatment. J Sleep Res. 1999;8:211-216.

25. Morisson F, Décary A, Petit D, et al. Daytime sleepiness and EEG spectral analysis in apneic patients before and after treatment with continuous positive airway pressure. Chest. 2001;119:45-52.

26. Montplaisir J, Whittom S, Michaud M, et al. Periodic leg movements during sleep and waking in narcolepsy. Neurology. 2005;64(supp. 1):A43.

27. Hilbert J, Mohsenin V. Can periodic limb movement disorder be diagnosed without polysomnography? A case-control study. Sleep Med. 2003;4:35-41.

28. Saskin P, Moldofsky H, Lue FA. Periodic movements in sleep and sleep-wake complaint. Sleep. 1985;8:319-324.

29. Rosenthal L, Roehrs T, Sicklesteel J, et al. Periodic movements during sleep. Sleep fragmentation, and sleep-wake complaints. Sleep. 1984;7:326-330.

30. Parrino L, Boselli M, Giovanni PB, et al. The cyclic alternating pattern plays a gate-control on periodic limb movements during non-rapid eye movement sleep. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1996;13:314-323.

31. Bastuji H, Garcia-Larrea L. Sleep/wake abnormalities in patients with periodic leg movements during sleep: Factor analysis on data from 24-h ambulatory polygraphy. J Sleep Res. 1999;8:217-223.

32. Bliwise D, Petta D, Seidel W, Dement W. Periodic leg movements during sleep in the elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1985;4:273-281.

33. Coleman RM, Bliwise DL, Sajben N, et al. Daytime sleepiness in patients with periodic movements in sleep. Sleep. 1982;5:191-202.

34. Youngstedt SD, Kripke DF, Klauber MR, et al. Periodic leg movements during sleep and sleep disturbances in elders. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998;53:M391-M394.

35. Karadeniz D, Ondze B, Besset A, Billiard M. Are periodic leg movements during sleep (PLMS) responsible for sleep disruption in insomnia patients? Eur J Neurol. 2000;7:331-336.

36. Mendelson WB. Are periodic leg movements associated with clinical sleep disturbance? Sleep. 1996;19:219-223.

37. Nicolas A, Lespérance P, Montplaisir J. Is excessive daytime sleepiness with periodic leg movements during sleep a specific diagnostic category? Eur Neurol. 1998;40:22-26.

38. Michaud M, Chabli A, Lavigne G, Montplaisir J. Arm restlessness in patients with restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 2000;15:289-293.

39. Chabli A, Michaud M, Montplaisir J. Periodic arm movements in patients with the restless legs syndrome. Eur Neurol. 2000;44:133-138.

40. American Sleep Disorders Association. EEG arousal: Scoring rules and examples. Sleep. 1992;15:174-184.

41. Sforza E, Nicolas A, Lavigne G, et al. EEG and cardiac activation during periodic leg movements in sleep: Support for a hierarchy of arousal responses. Neurology. 1999;52:786-791.

42. Bliwise DL, Keenan S, Burnburg D, et al. Inter-rater reliability for scoring periodic leg movements in sleep. Sleep. 1991;14:249-251.

43. Winkelman JW. The evoked heart rate response to periodic leg movements of sleep. Sleep. 1999;22:575-580.

44. Gosselin N, Lanfranchi P, Michaud M, et al. Age and gender effects on heart rate activation associated with periodic leg movements in patients with restless legs syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114:2188-2195.

45. Montplaisir J, Lanfranchi P, Whittom S, et al. Autonomic changes associated with periodic leg movements in narcolepsy and RLS. Neurology. 2005;64(suppl 1):A43.

46. Nicolas A, Michaud M, Lavigne G, et al. The influence of sex, age and sleep/wake state on characteristics of periodic leg movements in restless legs syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol. 1999;110:1168-1174.

47. Montplaisir J, Boucher S, Poirier G, et al. Clinical, polysomnographic, and genetic characteristics of restless legs syndrome: A study of 133 patients diagnosed with new standard criteria. Mov Disord. 1997;12:61-65.

48. Michaud M, Poirier G, Lavigne G, Montplaisir J. Restless legs syndrome: Scoring criteria for leg movements recorded during the suggested immobilization test. Sleep Med. 2001;2:317-321.

49. Michaud M, Dumont M, Selmaoui B, et al. Circadian rhythm of restless legs syndrome symptoms: Relationships with salivary melatonin, core body temperature and subjective vigilance. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:372-380.

50. Michaud M, Dumont M, Paquet J, et al. Circadian variation of the effects of immobility on symptoms of restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 2005;28:843-846.

51. Garcia-Borreguero D, Larrosa O, Granizo JJ, et al. Circadian variation in neuroendocrine response to L-dopa in patients with restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 2004;27:669-673.

52. The International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Validation of the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group rating scale for restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2003;4:121-132.

53. Birinyi PV, Allen RP, Lesage S, et al. Investigation into the correlation between sensation and leg movement in restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 2005;20:1097-1103.

54. Michaud M, Lavigne G, Desautels A, et al. Effects of immobility on sensory and motor symptoms of restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 2002;17:112-115.

55. Pelletier G, Lorrain D, Montplaisir J. Sensory and motor components of the restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 1992;42:1663-1666.