15 Sleep Disorders

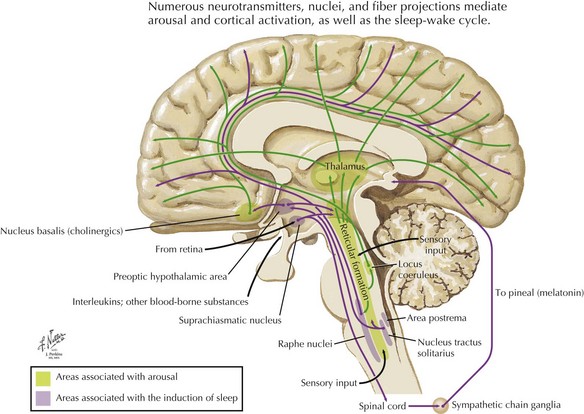

Neurotransmitters and Sleep

The primary neurochemical/physiology of the sleep-wake cycle is well defined (Fig. 15-1). Sleep onset depends on GABAergic circuitry within the anterior hypothalamus. In contrast, the posterior hypothalamus contains histamine and orexin or hypocretin pathways that promote wakefulness. Wakefulness and consciousness are mainly acetylcholine dependent; however, contributions are also made by norepinephrine, glutamate, and serotonergic pathways. REM sleep is modulated by the serotonergic, noradrenergic system and promoted by acetylcholine and glutamate. Additionally, specific cell populations either activate or inhibit REM.

Sleep Apnea Syndrome

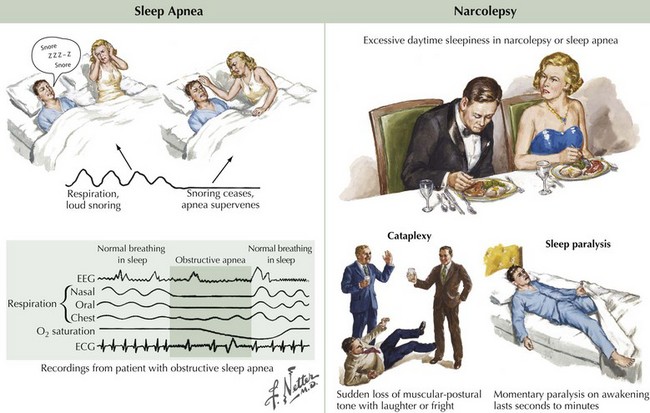

Clinical Presentation

Loud snoring, caused by upper airway tissue vibration, is a warning sign of sleep apnea syndrome. When the obstruction becomes complete, an apneic event occurs. Concomitantly, blood oxygen saturation decreases and carbon dioxide increases. When this develops, a sleep arousal occurs. Although the patient is usually unaware of the event, often the partner is aroused and frightened by the individual’s having ceased to breathe. Loud snoring, in combination with daytime sleepiness, raises the suspicion of clinically significant obstructive sleep apnea (Fig. 15-2A). Paradoxically, the majority of patients with obstructive sleep apnea do not report choking or gasping for breath, are unaware of their apneas, and often believe that they have had an adequate night’s sleep.

Narcolepsy

Clinical Presentation

The symptoms of the narcolepsy tetrad include excessive daytime sleepiness, which is present in almost all patients, and the ancillary symptoms of cataplexy, sleep paralysis, and hypnagogic hallucinations (Fig. 15-2B). One or more of these ancillary symptoms are present in about 50–60% of narcoleptics, and they are due to the inappropriate occurrence of partial episodes of REM sleep. During REM sleep, healthy individuals are often dreaming, and except for the extraocular and respiratory musculature, most muscles are paralyzed. This paralysis is subclinical in healthy individuals because it occurs while they are asleep.

Parasomnias

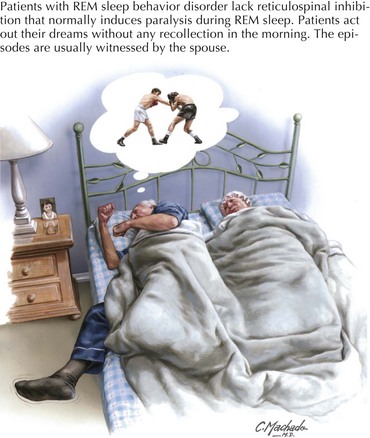

REM Behavior Disorder

Most healthy individuals are paralyzed and dreaming during REM sleep. The characteristic paralysis, sparing both eye movements and respiratory muscles, is from activation of inhibitory reticulospinal pathways, which results in an inhibition of anterior horn cells within the spinal cord, preventing patients from acting out dreams. In sleep paralysis, this otherwise normal phenomenon occurs while the patient is awake. In RBD, this activation fails to occur, resulting in the patient acting out a dream (Fig. 15-3).

Barion A, Zee PC. A clinical approach to circadian rhythm sleep disorders. [Review] [120 refs] Sleep Medicine. 2007 Sep;8(6):566-577.

Monti JM, Pandi-Perumal SR, Sinton CM, editors. Neurochemistry of Sleep and Wakefulness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Wise MS, Arand DL, Auger RR, et al. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Treatment of narcolepsy and other hypersomnias of central origin. [Review] [91 refs] Sleep. 2007 Dec 1;30(12):1712-1727.