Chapter 43 Skull Base Approaches

• Cranial base approaches are designed to provide greater tumor exposure compared to conventional cranial approaches, while avoiding retraction of normal brain structures. An understanding of the often complex anatomy is key to preserving the critical structures surrounding each approach.

• Selection of an appropriate approach for a specific tumor is determined by the cranial fossa involved and tumor extension, the ability to interrupt the tumor’s blood supply early, and relationship of the tumor with surrounding normal structures. For more extensive tumors, either combined approaches or staged operations may be required.

• Complications of skull base approaches include vascular, nerve, or brainstem injury; cosmetic deformity; and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. In many cases these complications may be avoided by mastery of the surgical anatomy, careful preoperative planning including appropriate structural and vascular imaging, intraoperative monitoring, and meticulous attention to detail during the exposure, osteotomies, and reconstruction.

• The primary indication for the transsphenoidal approach is midline sellar and suprasellar lesions such as pituitary adenomas; this surgical approach can be performed using endoscopic or microsurgical techniques.

• The extended subfrontal approach is excellent for intra- and extradural lesions of the anterior skull base, paranasal sinuses, as well as the sella, and midline clivus down to the foramen magnum. It is excellent for sinonasal malignancies, chordomas, and ethesioneuroblastomas.

• The transmaxillary and extended transmaxillary approaches are best suited for midline extradural lesions centered on the midportion of the clivus, such as chordomas and chondrosarcomas.

• Transoral approaches are excellent for addressing midline lesions of the lower clivus and upper cervical spine from degenerative, congenital, or rheumatic disorders.

• The frontotemporal approach with variations of the orbitozygomatic extension is among the most frequently used skull base approaches. It is applicable to vascular and neoplastic lesions involving the anterior and middle fossa, orbit, orbital apex and cavernous sinus, paraclinoid and parasellar regions, and basilar apex.

• The subtemporal transzygomatic with petrous apex resection is utilized for lesions involving the petrous apex, upper clivus, posterior cavernous sinus, Meckel’s cave, and the upper posterior fossa. Typical lesions resected via this approach include trigeminal schwannomas, petrous apex lesions such as cholesterol granulomas, cholesteatomas and chondrosarcomas, meningiomas involving the cavernous sinus and tentorium as well as smaller petroclival meningiomas, and vascular lesions in the region of the basilar artery.

• The preauricular subtemporal-infratemporal approach is an inferior extension of the subtemporal transzygomatic approach, and is better suited for lesions requiring lateral exposure of the mid and lower clivus, such as petroclival chondrosarcomas and cholesterol granulomas.

• Transpetrosal approaches provide an ideal ventral trajectory to the brainstem, particularly for posterior fossa tumors with significant extension above the tentorium, such as petroclival meningiomas.

• The extreme lateral transcondylar approach is well suited for lateral and ventral exposure of the caudal brainstem and upper cervical spinal cord at the level of the foramen magnum.

Skull base approaches were developed in response to a need to expose and maximally treat complex lesions at the base of the skull while minimizing retraction injury to normal neurological structures. As with any surgical approach, modules to the skull base are underpinned by a complete knowledge of the regional anatomy as well as appreciation of an often complex three-dimensional anatomy, supplemented by experience in cadaveric dissection. In many instances, a “skull base” approach implies an extension of classic cranial approaches, whereas in others, the approach is not implicit in typical neurosurgical training. Over the past 30 years, approaches in a circumferential fashion to the entire skull base have been developed and have been subjected to various classification schemes and terminologies. They may, however, be summarized as shown in Box 43.1.

Knowledge and expertise required in these approaches provide the fundamental knowledge for access to virtually every aspect of the base of the skull, and allow for selective implementation of part(s) of specific approaches when indicated by the respective pathology. This chapter provides an overview of approaches to the skull base, and for each module the relevant anatomy, indications, and technical principles with possible surgical pitfalls are discussed. This chapter is a summary that should not replace several extensive references on both the anatomy and surgery of the skull base,1–5 in addition to practice in the cadaveric laboratory and instruction from experts in cranial base surgery.

Anterior Skull Base Approaches

Transsphenoidal Approach

The primary indication for the transsphenoidal approach is midline sellar and suprasellar lesions, and it is the workhorse approach for most pituitary adenomas. Several authors have reported endonasal techniques of resection of other lesions, such as tuberculum sellae meningiomas and craniopharyngiomas.6 This approach is limited laterally by the internal carotid arteries; therefore, lesions extending laterally to this point cannot be resected completely. Either the microscope or the endoscope (either as the primary or assistive device) may be used for visualization. Current transsphenoidal instruments remain limited in the ability to apply standard microsurgical techniques of sharp dissection for intradural lesions, and intraoperative complications such as arterial injury are difficult to repair for this reason. Selected intradural lesions, such as tuberculum sellae meningiomas and craniopharyngiomas, may be removed via an extended transsphenoidal approach, provided an adequate arachnoid plane is visualized on preoperative imaging, and the tumor is primarily midline with no lateral extension beyond the carotid arteries or optic nerves. The caveat of an extended approach is an increased risk of postoperative CSF rhinorrhea, given the inherent difficulty of primarily repairing dural or bony openings in a watertight fashion. Dural substitutes, fibrin glue, postoperative lumbar CSF diversion, and nasoseptal mucosal flaps are useful adjuncts to prevent CSF leakage.

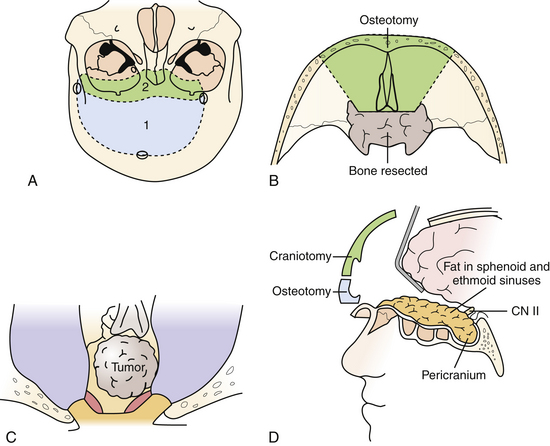

Extended Subfrontal Approach

This versatile approach is useful for intra- and extradural lesions of the anterior skull base, paranasal sinuses, as well as the sella, and midline clivus down to the foramen magnum. It is also better suited than the transmaxillary approach for intradural lesions in these areas. Furthermore, it can be adapted for more lateral exposure, including the cavernous sinus and frontotemporal area as needed. As such, it is useful for purely extradural lesions, such as for craniofacial resection of sinonasal malignancies, and for mixed intra- and extradural lesions such as esthesioneuroblastomas, chordomas, and chondrosarcomas (Fig. 43.1).

The patient is positioned supine with the head neutral and the body secured for tilting as required during the procedure for contralateral exposure. Brain relaxation and CSF diversion are facilitated by intraoperative placement of a lumbar drain. A bicoronal incision is performed behind the hairline and reflected anteriorly. A pericranial incision is made from behind the skin incision to maximize the available graft and the pericranium is reflected anteriorly as a separate layer to repair the frontal and ethmoid sinuses as well as the dura at the end of the surgery. Care is taken to preserve the supratrochlear and supraorbital bundles, which may emerge either from a notch or true foramen from above the orbital rim. In the case of a foramen, they are osteotomized with a small straight osteotome and outfractured with the scalp flap. The periorbita is dissected for a distance of approximately 3 cm to allow the orbitofrontal osteotomy to be sufficiently posterior, and the frontonasal suture is also exposed. At this point a low bifrontal craniotomy is performed, taking care not to lacerate the dura or the superior sagittal sinus. The subfrontal dura is mobilized off the orbital roofs bilaterally, sparing the cribriform plate region. A bilateral orbitofrontal osteotomy is then performed using the reciprocating saw, incorporating the orbital bar and through the nasoethmoidal complex in the midline, and circumventing the cribriform plate in order to spare the olfactory dura. The remaining cribriform plate is drilled until the olfactory dural sheath is exposed. Depending on the pathology and the preoperative state of the patient’s olfaction, the olfactory nerves can be preserved during this approach, particularly for when the pathology is primarily intradural. Following an osteotomy circumventing the cribriform plate, the dura is opened, and the olfactory tract and sulcus are identified. Arachnoid dissection is used to mobilize the olfactory tracts off their sulci, allowing the basal frontal lobes to relax without transmitting traction on the olfactory tracts. In more extensive primarily extradural lesions, particularly if the patient is anosmic, the entire complex can then be suture-ligated and divided from within the nasal cavity, allowing the frontal lobes to relax superiorly. The anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries are divided.

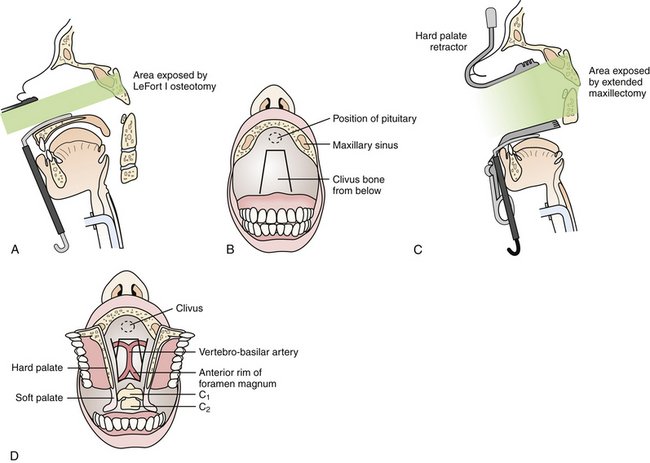

Transmaxillary and Extended Transmaxillary Approaches

This approach is best suited for midline extradural lesions centered on the midportion of the clivus, such as chordomas and chondrosarcomas (Fig. 43.2). The exposure is also well suited for lesions extended superiorly up to the sella turcica. The lateral limits of this exposure include the cavernous sinus and carotid arteries, and the pterygoid space. Depending on the extent of disease, however, the lower clivus, anterior cervical spine, or lateral infratemporal space may be accessed via extended maxillotomy approaches.

Following tumor resection, if there is a dural defect it is repaired with an abdominal fascial graft as well as fibrin glue, followed by abdominal fat and, for larger bony defects, the repair is reinforced with titanium mesh, which is secured with screws. The maxillary osteotomy is reapproximated with titanium plates and screws. A lumbar drain is placed for 3 to 5 days postoperatively to promote a watertight dural repair and prevent CSF fistula formation.

Transoral Approach

Preoperatively, the oral opening must be assessed to be sufficiently mobile and large enough to facilitate the approach. The patient is positioned supine with a variable amount of neck extension depending on the location and nature of the pathology. A self-retaining pharyngeal retractor is placed, and the soft palate is retracted superiorly using a nasally placed rubber cathether. A midline longitudinal incision is then performed along the posterior pharyngeal wall, and the longus colli and capitis muscles are retracted laterally together with the pharyngeal mucosa. For more exposure superiorly, a midline incision through the soft palate can be performed down to the uvula, and the palate divided in the midline. The anterior tubercle of C1 and the C2 vertebrae are thus exposed. Superiorly, the lower portion of the bony septum may be partially resected to expand the clival exposure. Any compressive osteofibrotic pannus or tumor is resected. Dural penetration is repaired in a similar manner as described in the transmaxillary approach, and the pharyngeal mucosa and muscles as well as the palate are all closed in separate layers. Postoperatively, the patient is kept intubated until oropharyngeal swelling has subsided, and nasogastric tube feeding is continued until the mucosal repair has sufficiently healed.

Anterolateral Skull Base Approaches

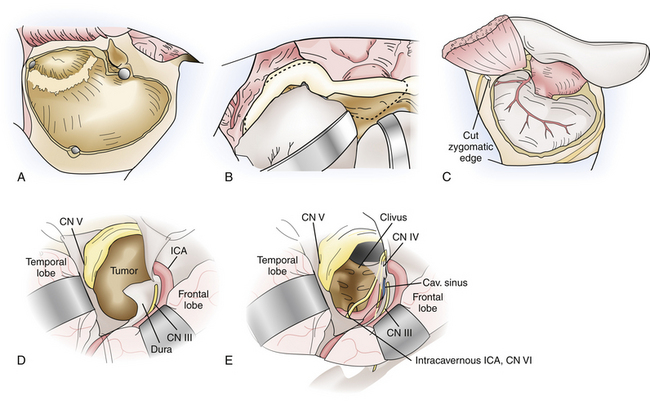

Frontotemporal Orbitozygomatic Approach

The frontotemporal approach with variations of the orbitozygomatic extension is among the most frequently implemented skull base approaches. Vascular and neoplastic lesions involving the anterior and middle fossae, orbit, orbital apex and cavernous sinus, paraclinoid and parasellar regions, and basilar apex are accessible with avoidance of brain retraction (Fig. 43.3).

At this point the periorbita and subfrontal dura are carefully dissected off the orbital roof and walls. The temporalis and masseter muscles are sharply freed from the zygomatic arch, and approximately 1 cm of zygoma is exposed to allow placement of a titanium plate. The inferior orbital fissure is palpated from both the intraorbital and cranial compartments. Malleable brain ribbons are used to then protect the globe and frontal lobe, and a reciprocating saw is used to perform the orbitozygomatic osteotomy. The medial cut is made just lateral to the supraorbital notch, angled from lateral to medial and incorporating at least two thirds of the anteroposterior extent of the orbital roof, within safe distance of the superior orbital fissure posteriorly. Too shallow osteotomies after the remaining lesser wing of the sphenoid is rongeured are associated with persistent postoperative pulsatile enophthalmos and should thus be avoided. Laterally, a second cut is made from the inferior orbital fissure to the level of the zygomaticofacial foramen. This is connected to another lateral cut from the anterior, inferior edge of the zygoma, also directed toward the inferior orbital fissure. The final cut is performed obliquely from posterior to anterior at the root of the zygoma and its transition point with the squamosal temporal bone. The osteotomy is completed with gentle fracturing using a small osteotomy and mallet, and removed as a single piece, freeing any remaining attached periorbita or muscle.

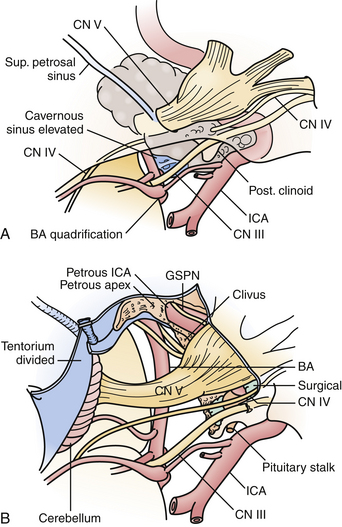

Subtemporal Transzygomatic Approach with Petrous Apex Resection

This approach is well suited for lesions involving the petrous apex, upper clivus, posterior cavernous sinus and Meckel’s cave, including limited extension of pathology into the upper posterior fossa. Typical lesions resected via this approach include trigeminal schwannomas; petrous apex lesions such as cholesterol granulomas, cholesteatomas, and chondrosarcomas; meningiomas involving the cavernous sinus and tentorium as well as smaller petroclival meningiomas; and vascular lesions in the region of the basilar apex (Fig. 43.4).

A predominantly temporal craniotomy is then performed, and additional temporal bone is craniectomized as necessary to remove obstructing bone from the floor of the middle fossa. The zygomatic osteotomy is then performed, from just lateral to the lateral wall of the orbit, preserving the zygomaticofacial nerve, to the root of the zygoma. If the condylar fossa is included in the osteotomy, the temporal dural vessels are first followed to the foramen spinosum, which is a medial safe landmark for the condylar cuts. An osteotomy that transgresses medial to the foramen spinosum puts the petrous internal artery at risk. Additional cuts are then made from the foramen spinosum medially to the posterior aspect of the condylar fossa and anterior zygomatic cut, laterally. Positioning titanium plates prior to the osteotomy ensures perfect realignment at the end of the surgery to prevent complications related to TMJ dysfunction.

Once the petrosectomy is completed, the petroclival dura is opened. For lesions extending into the posterior cavernous sinus, it is necessary to split the fascicles of the trigeminal root from within Meckel’s cave, reaching the posteromedial border of the cavernous sinus beyond the distal petrous ICA and petrolingual ligament. Alternatively, the trigeminal root may be mobilized superiorly. This is facilitated by opening the temporal lobe dura above the tentorium, and dividing the tentorium and superior petrosal sinus.7

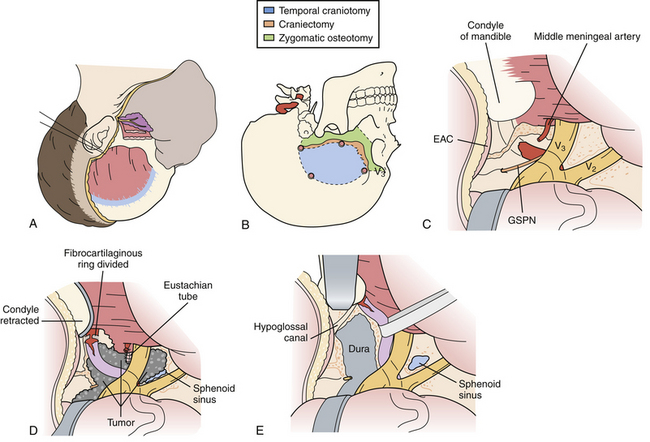

Preauricular Subtemporal-Infratemporal Approach

The subtemporal-infratemporal approach is an inferior extension of the subtemporal transzygomatic approach, and is better suited for lesions requiring lateral exposure of the mid and lower clivus, such as petroclival chondrosarcomas and cholesterol granulomas (Fig. 43.5). In addition to an anterior petrosectomy, Glasscock’s space is also drilled and the eustachian tube divided, allowing the petrous internal carotid artery to be completed mobilized anteriorly.

Lateral and Posterolateral Skull Base Approaches

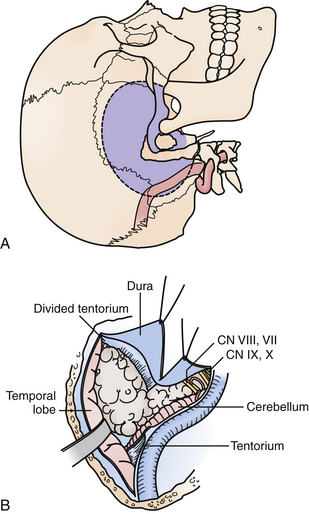

Transpetrosal Approaches: Retrolabyrinthine, Partial Labyrinthectomy/Petrous Apicectomy, Translabyrinthine, Transcochlear

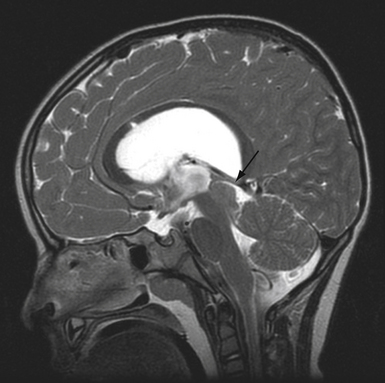

These approaches provide a more ventral trajectory to the brainstem, particularly for posterior fossa tumors with significant extension above the tentorium, of which petroclival meningiomas are most typical (Fig. 43.6). Extensive chordomas or chondrosarcomas with brainstem compression from a significant intradural component may also require a transpetrosal approach, as it would allow tumor resection with direct visualization of critical intradural structures. Finally, vascular lesions of the mid and lower basilar arteries, including basilar apex aneurysms in the setting of a low bifurcation, and vertebrobasilar junction lesions may also be better suited with a trajectory from the presigmoid region.

Selection of the type of posterior transpetrosal approach depends on a number of factors, including the preoperative hearing status of the patient, the size and dominance of the ipsilateral sigmoid sinus, and extent of disease. Hearing is preserved in the retrolabyrinthine and partial labyrinthectomy approaches. In the partial labyrinthectomy/petrous apicectomy (PLPA), the superior and posterior semicircular canals are waxed as they are opened, in order to prevent leakage of endolymph and hearing loss. Preoperative vascular imaging is carefully reviewed. In cases in which the sigmoid sinus is small, a retrolabyrinthine approach is usually sufficient to have an adequate opening of the presigmoid dura. Otherwise, a more extensive drilling of the labyrinth is performed.

Under the microscope, the entire mastoid is then decorticated with a larger bur on a microdrill, exposing the mastoid antrum air cells, and skeletonizing the sigmoid sinus dura and middle fossa floor, or tegmen tympani. The bone overlying the lateral semicircular canal is gradually appreciated proceeding through the mastoid air cells. Immediately anteroinferior to the lateral canal is the posterior genu of the facial nerve. The superior and posterior semicircular canals are then skeletonized. For a PLPA approach, the common crus is opened and filled with wax to prevent leakage of endolymph in an effort to preserve hearing, and the superior and posterior semicircular canals are then resected. This step increases the bony exposure of the petrous apex, which is then drilled. In certain cases, the retrosigmoid bone may be removed as well, allowing the sigmoid sinus to be retracted gently if necessary, and allowing portions of tumor to be resected through a retrosigmoid dural opening. In a translabyrinthine approach, the entire labyrinth is removed to the level of the vestibule, and the bone overlying the internal auditory canal is unroofed. Rarely is a total petrosectomy required for adequate brainstem exposure. In this approach, the entire labyrinth is removed, and the facial nerve is completely skeletonized from the cerebellopontine angle cistern to the fibrous ring at the stylomastoid foramen, allowing it to be mobilized anteriorly after division of the GSPN, albeit with an attendant, at least temporary, postoperative facial weakness. In a manner similar to the preauricular subtemporal-infratemporal approach described previously, the petrous ICA is unroofed and displaced anteriorly. The remaining temporal bone is drilled away, protecting the jugular bulb and lower cranial nerves anteriorly.

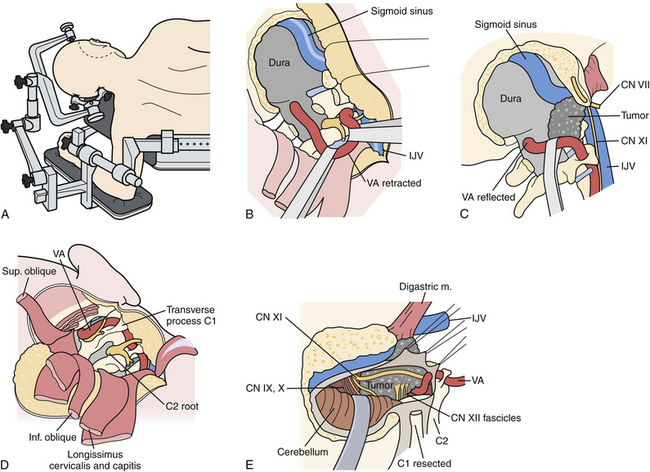

Extreme Lateral Approach

This approach is ideally suited for lateral and ventral exposure of the caudal brainstem and upper cervical spinal cord at the level of the foramen magnum. Several variations of this approach have been described, including the retrocondylar approach, the partial transcondylar approach, the transtubercular approach, true transcondylar approach, transjugular approach, and transfacetal approach (Fig. 43.7).8 For the purpose of this chapter, only the partial and complete transcondylar approaches will be described. Generally, the partial transcondylar approach is sufficient for exposure of ventrally situated intradural lesions at the lower brainstem. A complete transcondylar approach is most frequently indicated for extradural lesions that involve the condyle and lower clivus, such as chordomas.

The patient is placed in a full lateral position with the contralateral arm hung over the edge of the operating table with a sling or arm rest. The head is secured with pin fixation and rotated slightly toward the surgeon, neck flexed and apex dropped slightly toward the floor. Different incisions have been described for this approach. We prefer a C-shaped incision beginning superiorly in the posterior temporal region above the ear down in a curvilinear fashion behind the mastoid and toward the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. A skin flap is raised, above the muscle but incising the fascial attachment of the sternocleidomastoid such that it is mobilized forward together with this superficial layer, exposing the entire proximal attachment of the splenius capitis muscle. The remaining muscles are elevated in layers. The next muscle is the splenius capitis, which is incised off the mastoid process. At this point the occipital artery is identified in the underlying fascia, superficial to the semispinalis capsis and either below or running through the longissimus capitis. These two muscles are then elevated, exposing the muscles forming the suboccipital triangle, namely, the superior and inferior obliques and rectus capitis muscles.

At this point the key step is to safely identify the vertebral artery, typically the V3 segment first. The microscope is used at this point. Immediately, inferior to the mastoid tip is the transverse process of C1, which is easily palpated. The attachments of the superior and inferior oblique muscles as well as the levator scapula are identified. The micro-Doppler is used to identify the V3 vertebral artery above the C1 arch and within the suboccipital triangle. The oblique muscles are disconnected from the transverse process of C1 and reflected medially. Subperiosteal dissection on the superior border of the posterior arch of C1 usually exposes the vertebral artery outside its surrounding venous plexus. Venous bleeding is controlled with careful bipolar coagulation and injection with fibrin glue. A fairly consistent muscular branch of the vertebral artery is encountered emerging from the suboccipital triangle; it is coagulated or clipped and divided. The dissection proceeds medially until the vertebral artery curves toward its dural penetration. The fascial tissue medial to this is incised down to the foramen magnum dura. The C1 foramen transversarium is unroofed with a high-speed drill and small Kerrison rongeurs, and the lateral third of the C1 posterior arch is removed. The V3 vertebral artery is now rotated medially, away from the occipital condyle and occipitoatlantal joint.

Complications of Skull Base Approaches

Cosmetic issues have great importance even in larger skull base operations,9 as they may influence the patient’s self-perception and overall satisfaction with care. Keeping cranial incisions behind the hairline or within natural skin creases, preservation of scalp neurovasculature, careful mobilization of musculofascial layers with avoidance of cautery, careful replacement of bone flaps and osteotomy pieces with titanium mesh or bone substitute to restore normal cranial contours, and avoidance of cranial nerve and sensorimotor deficits all contribute to optimizing the cosmetic outcome of the operation.

Conclusions

Current skull base approaches allow circumferential access to all areas of the skull base; however, sound understanding of the relevant anatomy, fellowship training supplemented by time in the cadaver laboratory, strict attention to detail for all stages of the operation to prevent complications, and ability to treat complications should they occur are all requisites of ensuring a successful outcome.

Cappabianca P., Cavallo L.M., Esposito F., et al. Extended endoscopic endonasal approach to the midline skull base: the evolving role of transsphenoidal surgery. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg. 2008;33:151-199.

Rhoton A.L. Rhoton’s Cranial Anatomy and Surgical Approaches. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

Sekhar L., Fessler R. Atlas of Neurosurgical Techniques: Brain. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2006.

Sekhar L., De Oliveira E. Cranial Microsurgery: Approaches and Techniques. Stuttgart: Thieme; 1999.

Salas E., Sekhar L.N., Ziyal I.M., et al. Variations of the extreme-lateral craniocervical approach: anatomical study and clinical analysis of 69 patients. J Neurosurg. 1999;90(Suppl 2):206-219.

Please go to expertconsult.com to view the complete list of references.

1. Sekhar L., Fessler R. Atlas of Neurosurgical Techniques: Brain. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2006.

2. Sekhar L., De Oliveira E. Cranial Microsurgery: Approaches and Techniques. Stuttgart: Thieme; 1999.

3. Wanibuchi M., Friedman A., Fukushima T. Photo Atlas of Skull Base Dissection: Techniques and Operative Approaches. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2008.

4. Donald P. Surgery of the Skull Base. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998.

5. Rhoton A.L. Rhoton’s Cranial Anatomy and Surgical Approaches. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

6. Cappabianca P., Cavallo L.M., Esposito F., et al. Extended endoscopic endonasal approach to the midline skull base: the evolving role of transsphenoidal surgery. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg. 2008;33:151-199.

7. Ziyal I., Salas E., Wright D., Sekhar L. The petrolingual ligament: the anatomy and surgical exposure of the posterolateral landmark of the cavernous sinus. Acta Neurochir. 1998;140(3):201-205.

8. Salas E., Sekhar L.N., Ziyal I.M., et al. Variations of the extreme-lateral craniocervical approach: anatomical study and clinical analysis of 69 patients. J Neurosurg. 1999;90(Suppl 2):206-219.

9. Sekhar L.N. The cosmetic aspects of neurosurgery. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 2002;13(4):401-403.