15 Skin, nails and hair

Introduction

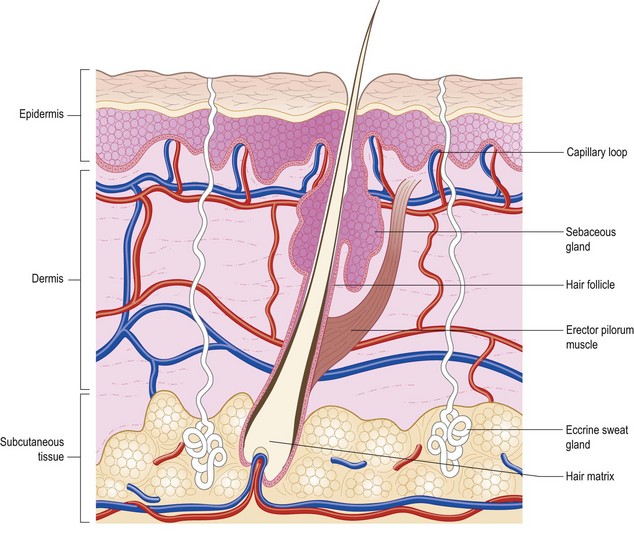

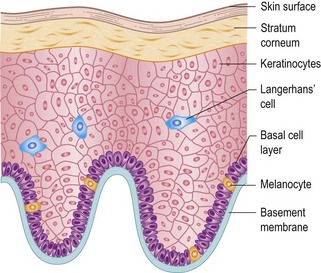

In the human body, the skin is the largest organ. Forming a major interface between man and his environment, it covers an area of approximately 2 m and weighs about 4 kg. The structure of human skin is complex (Figs 15.1 and 15.2), consisting of a number of layers and tissue components with many important functions (Box 15.1). Reactions may occur in any of the components of human skin and their clinical manifestations reflect, among other factors, the skin level in which they occur and sometimes act as a ‘window’ of systemic changes elsewhere in the body.

Examination

Colour and pigmentation

Pallor can have many causes. It may be:

Normal skin contains varying amounts of brown melanin pigment. Brown pigmentation due to deposited haemosiderin is always pathological. Albinism is an inherited generalized absence of pigment in the skin; a localized form is known as piebaldism. Patches of white and darkly pigmented skin (vitiligo) (Fig. 15.3) are due to a local and complete absence of melanocytes. Several autoimmune endocrine disorders are associated with vitiligo.

More or less generalized pigmentation may also be seen in the following:

Haemochromatosis, in which the skin has a peculiar greyish-bronze colour with a metallic sheen, due to excessive melanin and iron pigment.

Haemochromatosis, in which the skin has a peculiar greyish-bronze colour with a metallic sheen, due to excessive melanin and iron pigment.

Chronic arsenic poisoning, in which the skin is finely dappled affecting covered more than exposed parts.

Chronic arsenic poisoning, in which the skin is finely dappled affecting covered more than exposed parts.

Argyria, in which the deposition of silver in the skin produces a diffuse slate-grey hue.

Argyria, in which the deposition of silver in the skin produces a diffuse slate-grey hue.

Localized pigmentation may be seen in pellagra and in scars of various kinds, particularly those due to X-irradiation therapy. Venous hypertension in the legs is often associated with chronic purpura, leading to haemosiderin pigmentation. The mixture of punctate and fresh purpura and haemosiderin may produce a golden hue on the lower calves and shins. Pigmentation may also occur with chronic infestation by body lice. Erythema ab igne, a reticular pattern of pigmentation, can be seen in patients who use local heat to relieve chronic pain, or on the shins of people who habitually sit too near a fire. Livedo reticularis, a web-like pattern of reddish–blue discoloration mostly involving the legs, occurs in autoimmune vasculitis, especially in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and antiphospholipid syndrome, when it is associated with cerebral infarction. The violet-coloured lesions of lichen planus are slightly raised, flat-topped papules (Fig. 15.4). Psoriasis usually presents as a symmetrical plaque on extensor surfaces (Fig. 15.5). Keloid consists of raised and inflammed, overgrown tender scar tissue (Fig. 15.6).

Skin lesions and eruptions

Skin eruptions and lesions should be examined with special reference to their morphology, distribution and arrangement. The terminology of skin lesions is summarized in Boxes 15.2 and 15.3. Colour, size, consistency, configuration, margination and surface characteristics should be noted.

Box 15.2 Primary skin lesions

a glossary of dermatological terms

| Macule | Non-palpable area of altered colour |

| Papule | Palpable elevated small area of skin (<0.5 cm) |

| Plaque | Palpable flat-topped discoid lesion (>2 cm) |

| Nodule | Solid palpable lesion within the skin (>0.5 cm) |

| Papilloma | Pedunculated lesion projecting from the skin |

| Vesicle | Small fluid-filled blister (<0.5 cm) |

| Bulla | Large fluid-filled blister (>0.5 cm) |

| Pustule | Blister containing pus |

| Wheal | Elevated lesion, often white with red margin due to dermal oedema |

| Telangiectasia | Dilatation of superficial blood vessel |

| Petechiae | Pinhead-sized macules of blood |

| Purpura | Larger petechiae which do not blanch on pressure |

| Ecchymosis | Large extravasation of blood in skin (bruise) |

| Haematoma | Swelling due to gross bleeding |

| Poikiloderma | Atrophy, reticulate hyperpigmentation and telangiectasia |

| Erythema | Redness of the skin |

| Burrow | Linear or curved elevations of the superficial skin due to infestation by female scabies mite |

| Comedo | Dark horny keratin and sebaceous plugs within pilosebaceous openings |

Box 15.3 Secondary skin lesions that evolve from primary lesions

| Scale | Loose excess normal and abnormal horny layer |

| Crust | Dried exudate |

| Excoriation | A scratch |

| Lichenification | Thickening of the epidermis with exaggerated skin margin |

| Fissure | Slit in the skin |

| Erosion | Partial loss of epidermis which heals without scarring |

| Ulcer | At least the full thickness of the epidermis is lost. Healing occurs with scarring |

| Sinus | A cavity or channel that allows the escape of fluid or pus |

| Scar | Healing by replacement with fibrous tissue |

| Keloid scar | Excessive scar formation (see Fig. 15.6) |

| Atrophy | Thinning of the skin due to shrinkage of epidermis, dermis or subcutaneous fat |

| Stria | Atrophic pink or white linear lesion due to changes in connective tissue |

Morphology of skin lesions

Distribution of skin lesions

Consider the distribution of an eruption by looking at the whole skin surface:

Is it symmetrical or asymmetrical? Symmetry often implies an internal causation, whereas asymmetry may imply external factors.

Is it symmetrical or asymmetrical? Symmetry often implies an internal causation, whereas asymmetry may imply external factors.

Is the eruption centrifugal (radiating from the centre) or centripetal (radiating to the centre)? Certain common diseases such as chickenpox and pityriasis rosea are characteristically centripetal, whereas erythema multiforme and erythema nodosum are centrifugal. Smallpox, now eradicated, was also centrifugal.

Is the eruption centrifugal (radiating from the centre) or centripetal (radiating to the centre)? Certain common diseases such as chickenpox and pityriasis rosea are characteristically centripetal, whereas erythema multiforme and erythema nodosum are centrifugal. Smallpox, now eradicated, was also centrifugal.

A disease may exhibit a flexor or an extensor bias in its distribution: atopic eczema in childhood is characteristically flexor, whereas psoriasis in adults tends to be extensor.

A disease may exhibit a flexor or an extensor bias in its distribution: atopic eczema in childhood is characteristically flexor, whereas psoriasis in adults tends to be extensor.

Are only exposed areas affected, implicating sunlight or some other external causative factor?

Are only exposed areas affected, implicating sunlight or some other external causative factor?

If sunlight is suspected, are areas normally in shadow involved?

If sunlight is suspected, are areas normally in shadow involved?

Localized distributions may point immediately to an external contact as the cause, for example contact dermatitis from nickel earrings, lipstick dermatitis, etc.

Localized distributions may point immediately to an external contact as the cause, for example contact dermatitis from nickel earrings, lipstick dermatitis, etc.

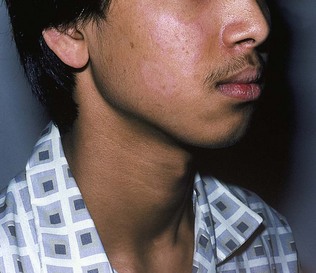

Swelling of the eyelids is an important sign. Without redness and scaling, bilateral periorbital oedema may indicate acute nephritis, nephrosis or trichinosis. If there is irritation, contact dermatitis is the probable diagnosis. Dermatomyositis often produces swelling and heliotrope-coloured erythema of the eyelids without scaling of the skin. In Hansen’s disease (leprosy), the skin lesions may be depigmented or reddened, with a slightly raised edge; they are also anaesthetic to pinprick testing (Fig. 15.7) and mainly located in skin that is normally cooler than core body temperature.

The hair

Growth of hair

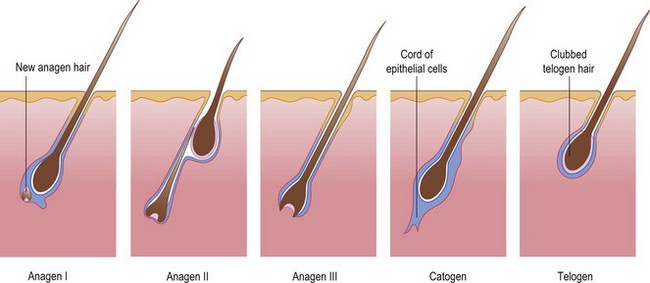

Unlike other epithelial mitotic activity that is continuous throughout life, the growth of hair is cyclic (Fig. 15.8), the hair follicle going through alternating phases of growth (anagen) and rest (telogen). Anagen in the scalp lasts 3-5 years; telogen is much shorter, at about 3 months. Catogen is the conversion stage from active to resting and usually lasts a few days. The duration of the anagen phase determines the length to which hair in different body areas can grow. On the scalp, there are on average about 100 000 hairs. The normal scalp may shed as many as 100 hairs every day as a normal consequence of growth cycling. These proportions can be estimated by looking at plucked hairs (trichogram): the ‘root’ of a telogen hair is non-pigmented and visible as a white, club-like swelling. Normally 85% of scalp hairs are in anagen and 15% in telogen.

Alopecia

Hair loss (alopecia) has many causes. It is convenient to subdivide alopecia into localized and diffuse types. In addition, the clinician should determine whether the alopecia results in scarring and, hence, permanent hair loss (Box 15.5).

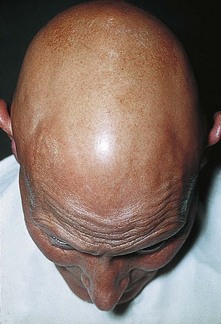

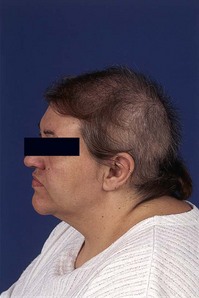

Scalp hair loss at the temples and crown, with the growth of male-type body hair, is characteristic of women with virilizing disorders. Metabolic causes of diffuse hair loss in women include hypothyroidism and severe iron deficiency anaemia. Antimitotic drugs may affect the growing hair follicles, producing a diffuse loss of anagen hairs, which are pigmented throughout their length. Dramatic metabolic upsets, such as childbirth, starvation and severe toxic illnesses, may precipitate follicles into the resting phase, producing an effluvium of telogen hairs 3 months later, when anagen begins again. This is called telogen alopecia. In the autoimmune disorder alopecia totalis (Fig. 15.9), there is complete loss of hair. Self-inflicted traction alopecia (Fig. 15.10) may indicate psychological problems.

The nails

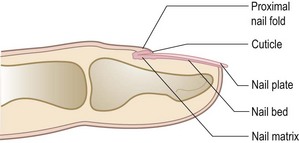

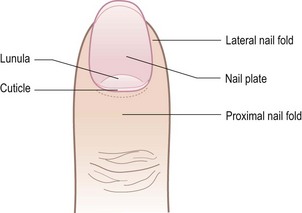

The nails should be examined carefully. The structure of the nail and nail bed is shown in Figures 15.11 and 15.12. The nail consists of a strong, relatively inflexible keratinous nail plate over the dorsal surface of the end of each digit, protecting the fingertip.

Nail matrix abnormalities

Thimble pitting of the nails is characteristic of psoriasis (Fig. 15.13), but eczema and alopecia areata may also produce pitting. A severe illness may temporarily arrest nail growth; when growth starts again, transverse ridges develop. These are called Beau’s lines and can be used to date the time of onset of an illness. Inflammation of the cuticle or nail fold (chronic paronychia) may produce similar changes. The changes described above arise from disturbance of the nail matrix.

Nail and nail-bed abnormalities

Disturbance of the nail bed may produce thick nails (pachyonychia) or separation of the nail from the bed (onycholysis). This occurs in psoriasis, but may be idiopathic. Long-term tetracyclines may induce separation when the fingers are exposed to strong sunlight (photo-onycholysis). The nail may be destroyed in severe lichen planus (Fig. 15.14) or epidermolysis bullosa (a genetic abnormality in which the skin blisters in response to minor trauma). Nails are missing in the inherited nail-patella syndrome. Splinter haemorrhages under the nails may result from trauma, psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis or other ‘collagen vascular’ diseases, bacterial endocarditis and trichinosis.

The nails in systemic disease

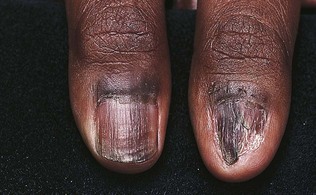

In iron-deficiency states, the fingernails and toenails become soft, thin, brittle and spoon-shaped. They lose their normal transverse convex curvature, becoming flattened or concave (koilonychia). The ‘half and half nail’, with a white proximal and red or brown distal half, is seen in some patients with chronic renal failure. Whitening of the nail plates may be related to hypoalbuminaemia, as in cirrhosis of the liver (leukonychia). Some drugs, notably antimalarials, antibiotics and phenothiazines, may discolour the nail. Nail-fold telangiectasia or erythema is a useful physical sign in dermatomyositis (Fig. 15.15), systemic sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. In dermatomyositis, the cuticle becomes ragged. In systemic sclerosis, loss of finger pulps may lead to curvature of the nail plates. An impaired peripheral circulation, as in Raynaud’s phenomenon, can lead to thinning and longitudinal ridging of the nail plate, sometimes with partial onycholysis. In bronchiectasis, the nails may take on a curved, yellow appearance (Fig. 15.16).

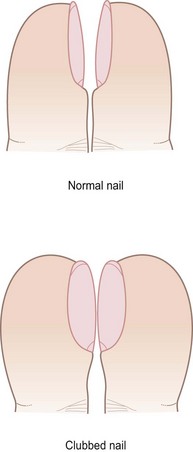

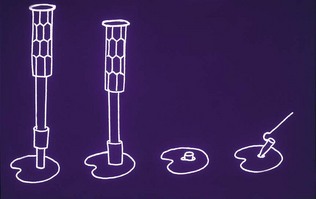

Clubbing

This is probably caused by hypervascularity and the opening of anastomotic channels in the nail bed. Rarely, clubbing may be congenital. The distal end of the digit becomes expanded, with the nail curved excessively in both longitudinal and transverse planes. Viewed from the side, the angle at the nail plate is lost and may exceed 180°. In normal nails, when both thumbnails are placed in apposition, there is a lozenge-shaped gap whereas, in clubbing, there is a reduction in this gap (Schamroth’s window test; Fig. 15.17). In hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy, there is clubbing of the fingers and thickening of the periosteum of the radius, ulna, tibia and fibula, which can be tender. (The causes of clubbing are listed in Box 15.6.)

Cutaneous manifestations of internal disease

Non-organ-specific autoimmune disorders

Several of the so-called collagen vascular diseases show characteristic cutaneous eruptions. Systemic lupus erythematosus, seen in women between puberty and the menopause, may show a symmetrical ‘butterfly’ erythema of the nose and cheeks. In discoid lupus, the cutaneous lesion is localized (Fig. 15.18). In polyarteritis nodosa, reticular livedo of the limbs with purpura, vasculitic papules and ulceration occurs. In scleroderma (systemic sclerosis), acrosclerosis of the fingertips with scarring, ulceration and calcinosis follows a Raynaud’s phenomenon of increasing severity. Dermatomyositis often presents with a heliotrope-coloured discoloration and oedema of the eyelids, and with fixed erythema over the dorsa of the knuckles and fingers (see Fig. 15.15) and over the bony points of the shoulders, elbows and legs. There is usually weakness of the proximal limb muscles. Dermatomyositis in the middle aged is associated in about 10% of cases with internal malignancy.

Skin pigmentation

Generalized, severe persistent pruritus in the absence of obvious skin disease may be due to systemic disease (Box 15.7). However, in older people with dry skin, it is common and of no systemic significance. Diabetes mellitus has a number of skin manifestations: of these, pruritus vulvae, pruritus ani, balanoposthitis and angular stomatitis are due to Candida overgrowth. Boils, follicular pustules or ecthyma are staphylococcal. Impetigo and erysipelas, streptococcal infections, are uncommon (Fig. 15.19). Eruptive xanthomata are a rare feature of uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (Fig. 15.20) produces reddish-brown plaques, usually on the shins, with central atrophy of the skin. It has to be distinguished from peritibial myxoedema (which is hypertrophic, not atrophic), the dermatoliposclerosis of chronic venous disease in the legs and the epidermal hypertrophy of chronic lymphatic obstruction.

Erythema nodosum is a condition in which tender, painful, red nodules appear, typically on the shins. They fade slowly over several weeks, leaving bruising, but never ulcerate. Sarcoidosis and drug sensitivity are the commonest causes, but other systemic disorders should be considered (Box 15.8).

Haemorrhage in the skin

Aggregations of extravasated red blood cells in the skin cause purpura (Fig. 15.21). Purpura may be punctate, from capillary haemorrhage or may form larger macules, depending on the extent of haemorrhage and the size of vessels involved. Palpable pupura should raise suspicion of leucocytoclastic vasculitis. The Hess test for capillary fragility involves deliberately inducing punctate purpura on the forearm by inflating a cuff above the elbow at 100 mmHg for 3 minutes. Sensitivity to drugs such as aspirin may cause widespread ‘capillaritis’.

The skin in sexually transmitted diseases

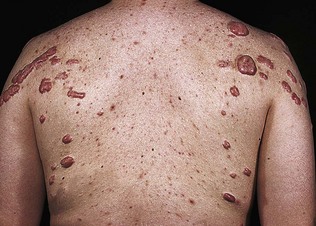

HIV-related syndromes have many cutaneous manifestations, including disseminated Kaposi’s sarcoma candidiasis, molluscum contagiosum, seborrhoeic dermatitis, folliculitis and oral hairy leukoplakia (Fig. 15.22).

Viral infection of the skin

Several of the most common viral infections and illnesses of childhood are characterized by fever and a distinctive rash (exanthem), including measles, varicella and rubella. In measles, upper respiratory symptoms are quickly followed by a characteristic maculopapular and erythematous rash. In rubella (German measles), the rash is more transient, with small papules, and associated with occipital lymphadenopathy and only slight malaise. The exanthem of varicella (chickenpox) is papulovesicular and centripetal, and there may be lesions in the mouth. In herpes zoster and herpes simplex infections (Fig. 15.23), there is a non-follicular papulovesicular rash in which the vesicles are planted in an inflamed base. The rash is painful. In herpes zoster, the rash follows a segmental distribution, in the skin of a dermatome. The vesicular lesion becomes encrusted (Fig. 15.24) and, later, secondary infection may occur.

Tumours in the skin

Exposure to the sun may, after many years, result in the development of many common skin tumours, for example squamous or basal cell carcinoma, or melanoma. These tumours are especially common in fair-skinned people. Basal cell carcinoma arises especially on the face, near the nose or on the forehead (Fig. 15.25). The lesion may be ulcerated with a firm, rounded edge, or papular. Melanomas may develop on the torso in men, and legs in females. They may be pigmented or amelanotic, and may in a third or so develop rapidly in a pre-existing benign mole (Fig. 15.26). Staging by assessing draining regional sentinel lymph nodes is becoming increasingly routine in cutaneous oncology. Seborrhoeic keratoses are familial resulting in a raised warty pigmented lesion found in the sun-exposed elderly, especially on the dorsa of hands as ‘liver spots’ (Fig. 15.27). A symptomatic pigmented skin lesion having an asymmetric, ragged border, three or more colours and diameter of >7 mm, particularly if it is increasing in size or bleeding and found on sun-damaged freckled skin, should be regarded as suspicious of malignant melanoma.

Special techniques in examination of the skin

Microscopic examination

Fungal infections

The skin between the toes (tinea pedis), the soles of the feet and the groin (tinea cruris) are the commonest sites of fungal infection. The lesions may be scaly or vesicular, tending to spread in a ring form with central healing (Fig. 15.28); macerated, dead, white, offensive-smelling epithelium is found in the intertriginous areas, such as the toe clefts.

Ringworm of the scalp (tinea capitis) is most common in children. It presents as round or oval areas of baldness covered with short, lustreless broken-off hair stumps. These hair stumps may fluoresce bright green under Wood’s light. Some fungi do not fluoresce with Wood’s light, however, and these can be detected only by microscopy and culture (Figs 15.29 and 15.30).

Skin biopsy

Biopsy of the skin is used not only for the excision of benign and malignant tumours but also to identify the nature of reactive and/or inflammatory lesions. Punch biopsy (Figs 15.31 and 15.32) is popular because of its convenience and results in minimal scarring. The biopsy can be studied by conventional histology, often supplemented by immunofluorescence, and sometimes immunohistochemistry or molecular biology, to identify specific proteins or genetic abnormalities. Skin biopsy of fresh tissue can be sent for the microbiology of unusual infections and is increasingly used in diagnosis and in assessing the progress of skin diseases.