4 Women

Gynaecological history

Menstrual history

What was the first day of your last normal menstrual period? (Patients may recall the last day of the period which is not contributory. Whether the period was normal or not is important, as sometimes vaginal blood loss may be that associated with an abnormal pregnancy.)

What was the first day of your last normal menstrual period? (Patients may recall the last day of the period which is not contributory. Whether the period was normal or not is important, as sometimes vaginal blood loss may be that associated with an abnormal pregnancy.)

How often do your menstrual cycles come?

How often do your menstrual cycles come?

How many days are there from the start of one menstrual cycle to the next? (It could be that the cycle is irregular; many women keep a diary of their menstrual periods and it is often helpful to see this.)

How many days are there from the start of one menstrual cycle to the next? (It could be that the cycle is irregular; many women keep a diary of their menstrual periods and it is often helpful to see this.)

How long do your periods last?

How long do your periods last?

How many heavy days are there? (With these two questions you are trying to guage the level of menstrual loss, so some estimate of the volume of flow is required: e.g. how many pads or tampons are used in the heaviest days.)

How many heavy days are there? (With these two questions you are trying to guage the level of menstrual loss, so some estimate of the volume of flow is required: e.g. how many pads or tampons are used in the heaviest days.)

Do you have bleeding between your periods? (If so, how much and when does it occur?)

Do you have bleeding between your periods? (If so, how much and when does it occur?)

Are your periods painful? (Some assessment of the degree of pain is necessary here, e.g. is medication used and, if so, what and how much? Does the pain stop you from carrying out your normal activities?)

Are your periods painful? (Some assessment of the degree of pain is necessary here, e.g. is medication used and, if so, what and how much? Does the pain stop you from carrying out your normal activities?)

Do you have any other symptoms with your periods? (This is an enquiry about premenstrual syndrome, in which a variety of symptoms can aggregate and then disappear as menstrual flow starts.)

Do you have any other symptoms with your periods? (This is an enquiry about premenstrual syndrome, in which a variety of symptoms can aggregate and then disappear as menstrual flow starts.)

How old were you when your periods first started? (Menarche.)

How old were you when your periods first started? (Menarche.)

Do you have any bleeding after sexual intercourse? (If so, ask for an estimate of how frequently this loss occurs and how heavy it is.)

Do you have any bleeding after sexual intercourse? (If so, ask for an estimate of how frequently this loss occurs and how heavy it is.)

What form of contraception are you using? (In the last two questions, it is first necessary to establish whether the patient is in a sexual relationship; this requires additional tact. The pattern of menstruation may be influenced by use of various contraceptive methods including the combined oestrogen/progestogen pill (combined oral contraception; COC), the progesterone-only pill (POP), injectable progestogens, various intrauterine contraceptive devices and newer progestogen-containing rings placed in the vagina.)

What form of contraception are you using? (In the last two questions, it is first necessary to establish whether the patient is in a sexual relationship; this requires additional tact. The pattern of menstruation may be influenced by use of various contraceptive methods including the combined oestrogen/progestogen pill (combined oral contraception; COC), the progesterone-only pill (POP), injectable progestogens, various intrauterine contraceptive devices and newer progestogen-containing rings placed in the vagina.)

Are you still having periods? or

Are you still having periods? or

When did you have your last period?

When did you have your last period?

Has there been any bleeding since your last period? (This relates to a definition of postmenopausal bleeding – generally defined as bleeding 6 months after the last period, unless the patient is taking hormone replacement therapy, in which case it is important to establish which type. Exclusion of organic pathology is mandatory in this situation.)

Has there been any bleeding since your last period? (This relates to a definition of postmenopausal bleeding – generally defined as bleeding 6 months after the last period, unless the patient is taking hormone replacement therapy, in which case it is important to establish which type. Exclusion of organic pathology is mandatory in this situation.)

Urinary tract and uterovaginal prolapse symptoms

Do you have a feeling of something coming down?

Do you have a feeling of something coming down?

Does the feeling go away overnight or when you lie down? (Symptomatic prolapse is gravity dependent except in the most severe cases.)

Does the feeling go away overnight or when you lie down? (Symptomatic prolapse is gravity dependent except in the most severe cases.)

Are there occasions when you don’t make it to the toilet in time?

Are there occasions when you don’t make it to the toilet in time?

Do you leak urine if you cough or sneeze?

Do you leak urine if you cough or sneeze?

When you pass urine, do you feel you have completely emptied your bladder?

When you pass urine, do you feel you have completely emptied your bladder?

When you are passing urine, can you squeeze hard enough to stop the flow? (Arresting flow mid stream is a good test of the strength of the pelvic floor.)

When you are passing urine, can you squeeze hard enough to stop the flow? (Arresting flow mid stream is a good test of the strength of the pelvic floor.)

Sexual symptoms

How severe is the pain – does sex have to stop?

How severe is the pain – does sex have to stop?

Does it happen every time you have sex, or only on some occasions? (If intermittent, ask how often this happens.)

Does it happen every time you have sex, or only on some occasions? (If intermittent, ask how often this happens.)

Can you say if the pain is superficial (near the outside) or deep on the inside? (Typical causes of deep dyspareunia include endometriosis and chronic pelvic inflammatory disease.)

Can you say if the pain is superficial (near the outside) or deep on the inside? (Typical causes of deep dyspareunia include endometriosis and chronic pelvic inflammatory disease.)

Do you have any other pains in the pelvic region other than the one brought on by sexual activity?

Do you have any other pains in the pelvic region other than the one brought on by sexual activity?

Obstetric history

How many times have you been pregnant? (Be aware that some patients may not indicate that they have had terminations of pregnancy.)

How many times have you been pregnant? (Be aware that some patients may not indicate that they have had terminations of pregnancy.)

What was the weight of the heaviest and the lightest baby?

What was the weight of the heaviest and the lightest baby?

How old were you when you had your first pregnancy?

How old were you when you had your first pregnancy?

How old are the children now? or

How old are the children now? or

How old is the youngest and how old is the oldest?

How old is the youngest and how old is the oldest?

Gynaecological examination

Full awareness of the privacy of the examination is mandatory. Contemporary attitudes to examination insist on a chaperone being present during any intimate examination (breast or pelvic examination) whether the person examining is male or female. General, abdominal and peripheral examination can be carried out without a chaperone, although it is preferable to have one present. Breast examination is not part of the gynaecological assessment in UK practice, unless there is a specific complaint related to the breasts. For a new consultation, a general examination is necessary and particularly relevant if an anaesthetic is anticipated. Make note of the patient’s general appearance, gait, demeanour, responsiveness and general affect. Details of the general physical examination are covered in Chapter 2; in the context of gynaecology, measurements of height and weight (giving the body mass index; BMI) and an assessment of body proportions (e.g. general or central obesity) are important. In ‘gynaecological endocrinological’ cases, the presence or absence of signs associated with hyperandrogenaemia (hirsutes, male pattern baldness, acne, increased muscle bulk) should be documented.

Abdominal examination

The system of examination described in Chapter 12 is recommended, but should focus on inspection and palpation; percussion and auscultation are less important in gynaecological practice. The presence or absence of scars should be noted. Laparoscopic scars can be subtle, particularly if tucked within the umbilicus. Occasionally (usually to avoid the risk of perforation through adhesions in the lower abdomen) the entry point for laparoscopic surgery may be via Palmer’s point in the mid-clavicular line, under the rib cage. Transverse suprapubic (Pfannenstiel’s) incisions may also be difficult to see in the suprapubic crease unless specifically looked for.

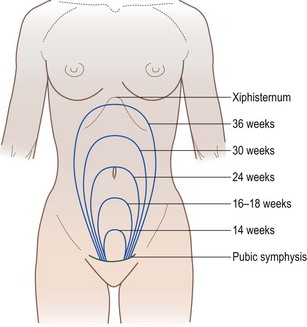

Suprapubic examination is particularly important as gynaecological masses arise out of the pelvis and the examining hand cannot get below it. Do this part of the abdominal palpation with the ulnar border of the left hand, starting at or around the umbilicus, and work your way down. When an abdominopelvic mass is present, its characteristics and size, either in centimetres measured from the symphysis pubis upwards, or estimated as weeks’ gestation of an equivalent-size pregnancy, are recorded (see Fig. 4.1). Note its consistency (hard if a fibroid, usually soft if a pregnancy), regularity (subserosal fibroids and ovarian masses are usually irregular) and the presence of any tenderness. It can sometimes be difficult to elicit such signs if there is a scar in the lower abdomen or if the patient is obese. If nothing is palpable arising out of the pelvis, it is reasonable to conclude that any pelvic swelling is less than the size of a 12-week pregnancy. If ascites is suspected, check the supraclavicular and inguinal lymph nodes and look for an associated hydrothorax.

Pelvic examination

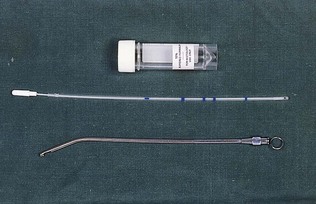

In gynaecology, pelvic examination (PE) is usually undertaken vaginally but it may also be performed rectally. The instruments used are shown in Figure 4.2. PE should always be preceded by abdominal examination. Patients will often be anxious and tense, so it is crucial to explain every step sensitively but clearly. Medical students should only undertake a PE in the presence of a supervisor; the same applies to trainees in gynaecology, except where specific permission has been granted by the trainer. In many centres, students begin to learn the technique of PE using simulated models.

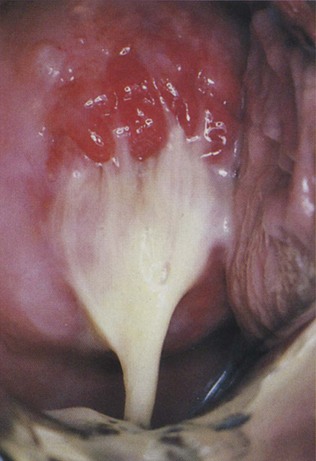

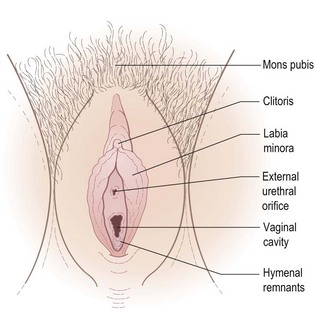

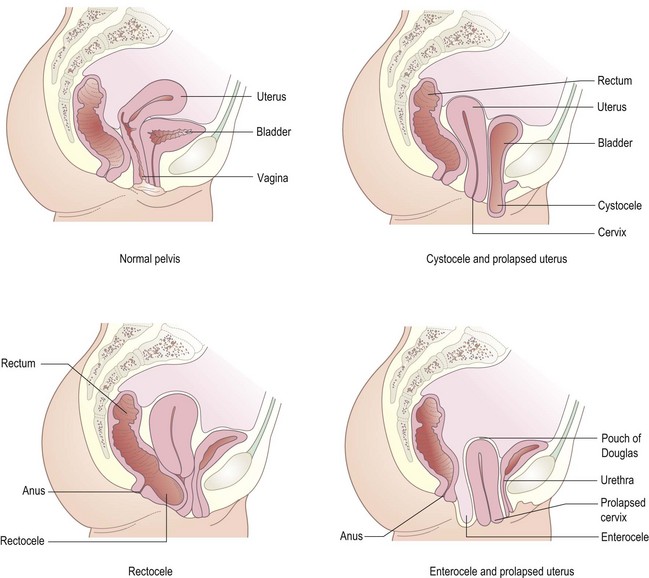

PE commences with inspection of the perineum in the dorsal or left lateral position and is followed by internal digital examination, using the index and middle fingers (one finger only may be possible if the vagina does not accommodate two). Generally, but not always, a speculum examination precedes the digital examination (if it is important to visualize any discharge, take swabs or take a cervical smear, the speculum should always be passed first; Fig. 4.3). In the event of the patient experiencing undue discomfort (be it speculum or digital), the examination should cease immediately. Make note of any inflammation, swelling, soreness, ulceration or neoplasia of the vulva, perineum or anus (Fig. 4.4). Small warts (condylomata acuminata) appearing as papillary growths may occur scattered over the vulva; these are due to infection with the human papilloma virus (HPV). Inspect the clitoris and urethra and ask the patient to strain and then cough to demonstrate any uterovaginal prolapse or stress incontinence (Fig. 4.5). If the patient has given a history of involuntary incontinence, it is important that the bladder is reasonably full and that more than one substantial cough is taken, as the first cough frequently fails to demonstrate leakage of urine. It is kind to press on the anus with a tissue or swab to reduce the risk of involuntary flatus, indicating to the patient the reason for doing so.

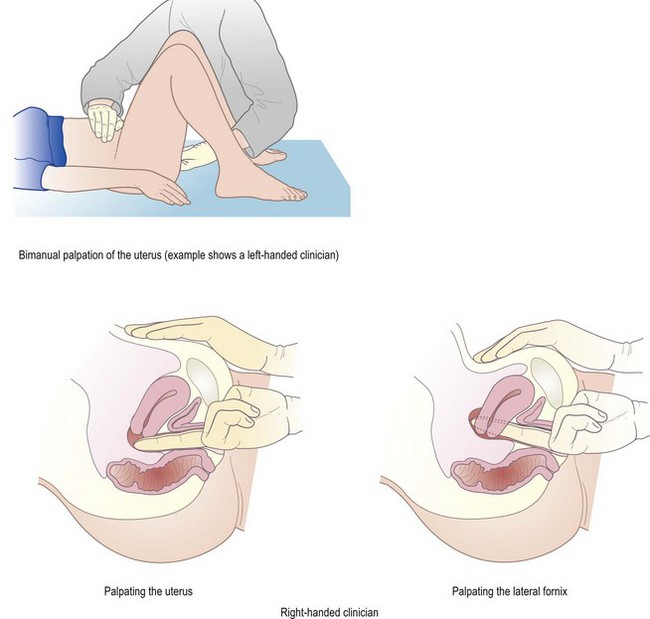

For the digital examination, disposable gloves are used and the examining fingers should be lightly lubricated with a water-based jelly. With the patient in the supine position and with her knees drawn up and separated, the labia are gently parted with the index finger and thumb of the left hand while the index finger of the right hand is inserted into the vagina, avoiding the urethral meatus and exerting a sustained pressure on the perineal body until the perineal musculature relaxes. Watch for any sign of discomfort. The full length of the finger is then introduced, assessing the vaginal walls in transit until the cervix is located. At this stage, a second finger can be inserted to improve the quality of the digital examination or, alternatively, a speculum can be used if a cervical smear is required. The examination is continued with the left hand placed on the abdomen above the symphysis pubis and below the umbilicus – the bimanual examination (Fig. 4.6). The hand provides gentle directional pressure to bring the pelvic viscera towards the examiner’s fingers in the vagina and serves to assess the size, mobility and regularity of masses. The cervix is then identified; it is approximately 3 cm in diameter, with a variably sized and shaped dimple in the middle, the cervical os. When the uterus is anteflexed and anteverted, the os is normally directed posteriorly. A retroverted uterus means the uterus is tipped backwards so that it aims towards the rectum instead of forward towards the belly. The consistency of the cervix is firm and its shape is irregular when scarred. Increased hardness of the cervix may be caused by fibrosis or carcinoma. As a ‘soft’ cervix indicates the possibility of pregnancy, even greater caution and gentleness is necessary. The mobility of the cervix is usually 1-2 cm in all directions, and testing this movement should produce only mild discomfort. If the cervix is moved when there is pelvic inflammation, particularly in association with ectopic pregnancy, extreme pain (cervical excitation) results.

Speculum examination

This is an essential part of a gynaecological examination. Several types of specula are available for use, including the bivalve type (e.g. Cusco’s) used for displaying the cervix (Fig. 4.7) and the single- or double-ended Sims’ (duckbill) speculum (Fig. 4.8) used to retract the vaginal walls. Occasionally, use is made of the Ferguson’s speculum, which may be required to inspect the cervix when vaginal prolapse is so severe that a bivalve speculum fails to provide a sufficient view. If a cervical smear is to be taken, care should be taken not to get lubricant on the cervix, as this can adulterate the quality of the sample, so the taking of the smear before digital examination is good practice without using excessive lubrication. The speculum should be warmed to body temperature and lubricated with water or a water-based jelly. All the necessary equipment, such as spatulas, slides, forceps, culture swabs, etc., should be prepared before the examination begins (see Fig. 4.2).

Carefully explain to the patient what will happen in the examination. Ask her to lie on her back with her feet together and knees drawn apart, as for the PE. Separate the labia and then the introitus with the thumb and index finger of the left hand and then insert the lightly lubricated bivalve speculum with the handle directly upwards, allowing it to be accommodated by the vagina. When it has been inserted to its full length, the blades of the speculum are opened and manoeuvred so that the cervix is fully visualized (the left hand should now be free to do this; see Fig 4.7). The screw adjuster or ratchet on the handle is then locked so that the speculum is maintained in place. Any discharge (see Fig 4.3) and the condition of the cervical epithelium, its colour, any ulceration or scars and retention cysts (nabothian follicles) should be noted.

Taking a cervical (Papanicolaou) smear

This involves the technique of liquid-based cytology, in which cells are obtained from the squamocolumnar junction (transformation zone). A spatula placed firmly in the cervical os and rotated through 360° or an endocervical brush may be used. If there is considerable discharge, with or without blood, the cervix can be cleansed using a cotton wool ball and a truer reflection of the cervix will result from the test. Taking a smear through a thick mucoid discharge may result in an unsatisfactory smear. Samples for Candida, Trichomonas, Neisseria gonorrhoea, Chlamydia and herpes may be obtained at the same time (see Ch. 21). The screw of the speculum is then released and the blades freed from the cervix so that it can be gently removed.

Assessment for prolapse

Assessment of the vaginal walls for prolapse or fistula is performed using a Sims’ speculum with the patient in the left lateral position. The best exposure is given by the Sims’ position, in which the pelvis is rotated by flexing the right thigh more than the left, and by hanging the right arm over the distant edge of the couch. A Sims’ speculum is inserted in much the same way as above, using the left hand to elevate the right buttock (see Fig. 4.8). The blade then deflects the rectum, exposing the urethral meatus, anterior vaginal wall and bladder base. Ask the patient to strain and note any vaginal wall prolapse. The level of the cervix is recorded as the speculum is withdrawn. The posterior vaginal wall can then be viewed by rotating the speculum through 180°. Uterine prolapse is called first degree if the cervix descends but lies short of the introitus, second degree if it passes to the level of the introitus and third degree (complete procidentia) if the whole of the uterus is prolapsed outside the vulva. Vaginal wall prolapse occurring with, or independent of, uterine prolapse consists of urethrocele, cystocele, rectocele or enterocele (prolapse of the pouch of Douglas). Several of these anatomical variations usually occur together (see Fig. 4.5).

Obstetric history

Obstetric examination

General examination

Again, this should follow the approach outlined in Chapter 2. In obstetric practice, height and weight (and calculated BMI) are important. As a general rule, labour is more efficient if the woman is above 152 cm in height, and hypertension, hyperglycaemia and anaesthetic difficulties are more common if the BMI is above 30 kg/m2. Record the blood pressure (it should be 140/90 or lower in a normal pregnancy) and examine carefully for oedema, not only in the ankles but also in the fingers (can she remove her rings easily?) and face. Breast examination is not indicated unless there is a complaint related to the breasts themselves, although it is common for women to ask questions related to breastfeeding.

Abdominal examination in pregnancy

Ask the patient to empty her bladder before the abdominal examination. Make sure the light is good, the room comfortably warm and that there is maximum exposure of the area to be examined (Box 4.1). Look for striae gravidarum, linea nigra, previous caesarean section or other scars and any visible fetal or other movements (unlikely before 30 weeks’ gestation but usually indicative of good health). Ideally the patient is examined flat, but she may be more comfortable semirecumbent. It is not usually an uncomfortable examination except in certain pathological situations. If part of the examination is likely to be painful, this should be left to the very end.

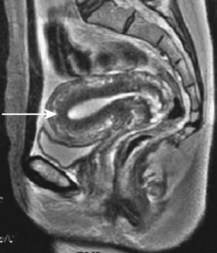

The size of the uterus (Fig. 4.9) is traditionally estimated by the fundal height (see Fig. 4.1): the distance from the symphysis pubis to the fundus (top portion) of the uterus. This is a useful measure, even though it is only one dimension of a globular mass. In a normal pregnancy, the fundal height is just above the symphysis pubis at 12 weeks’ gestation, at the umbilicus at 22 weeks and at the xyphisternum at 36 weeks. When the fundus is equidistant from the symphysis pubis and the umbilicus, the gestation is 16 weeks, and when equidistant from the xiphisternum and umbilicus, it is about 30 weeks. From 36 weeks, the fundal height is also dependent on the level of the presenting part, and therefore decreases as the presenting part descends into the pelvis. This is the phenomenon of a ‘lightening’ sensation experienced by the mother. The height of the fundus above the symphysis is usually recorded in centimetres and, from 20 weeks onwards, the number of centimetres above the symphysis is approximately in accord with the number of weeks of pregnancy, up to 38 weeks. This measurement is generally accepted to be objective and, importantly, is reproducible when different healthcare professionals participate in the same woman’s care. Common causes of deviation from these measurements include multiple pregnancy, multiple fibroids, intrauterine growth retardation and excess or reduced amniotic fluid volume (poly- and oligohydramnios respectively).

Next, determine the lie of the fetus (this is the relationship of the long axis of the fetus to the maternal spine – longitudinal usually, but sometimes oblique or transverse). To confirm the lie, the location of the fetal limbs and back should be identified (Fig. 4.10).

The presenting part refers to the part of the fetus that is felt on vaginal examination through the cervix (see vaginal examination in labour, below). The head may be presenting but the flexion of the head, or the extension of it, will govern what the presenting part is. In cephalic presentations, the smallest diameters presented to the pelvis occur when the head is well flexed. Thus, in a flexed head, it will be a vertex presentation, and in a deflexed head, it will be the brow or even the face. Flexion of the head is termed the attitude. These observations are not usually possible to ascertain on abdominal examination. For a breech presentation, an equivalent assessment is made to determine whether the breech is extended (frank), flexed (complete) or footling (incomplete). Once the presenting part has a relationship to the pelvis, that relationship can be vertical (the level) or rotational (the position) (Fig. 4.11). When the flexed head presents, the fetal occiput is termed the denominator. When the face presents, the denominator is the mentum (chin) and when the breech presents, it is the sacrum.

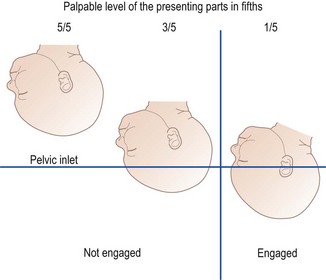

The presenting part is said to be engaged when the largest diameter has passed through the pelvic brim. It is conventional to estimate the number of fifths of the head that can be palpated through the abdominal wall and this indicates its level (Fig. 4.12). Thus, if there are three or more fifths palpable, the baby’s head will be unengaged. If less than three-fifths are palpable, then the baby’s head is probably engaged in the pelvis, but this does depend on the overall size of the fetal head and of the pelvis. Remember that the pelvic brim has an angle of approximately 45° to the horizontal when the mother is lying flat. If the abdominal wall is reasonably thin, the unengaged head can be palpated by the examiner’s fingers passing round its maximum diameter. This means it is above the pelvic brim. When this does not occur, the widest diameter must be below the examining fingers, and fixity of the baby’s head in the pelvis is also a guide. This means it is engaged. Engagement will usually occur as the leading edge of the baby’s head, on vaginal examination, reaches the level of the ischial spines (zero station).

Fetal movements, both as reported by the mother and observed by the examiner during the examination, are noted. An estimate is made of the fetal size and volume of liquor by a combination of palpation and ballottement. This requires considerable practice. Last, the fetal heart rate (FHR) (normally between 115 and 160 beats/min) is recorded either using a Pinard stethoscope (Fig 4.13) or, more often, with a sonicaid device.

Vaginal examination in labour

Is the cervix anterior, mid position or posterior?

Is the cervix anterior, mid position or posterior?

What is the consistency of the cervix – hard, firm or soft?

What is the consistency of the cervix – hard, firm or soft?

Is the cervix effaced (thinned)?

Is the cervix effaced (thinned)?

What is the presenting part? Assuming a head/cephalic presentation, is the presenting part a vertex (posterior fontanelle palpable through the cervical os), a deflexed head (anterior fontanelle palpable) or, unusually, a brow (supraorbital ridges palpable) or face (mentum or chin)?

What is the presenting part? Assuming a head/cephalic presentation, is the presenting part a vertex (posterior fontanelle palpable through the cervical os), a deflexed head (anterior fontanelle palpable) or, unusually, a brow (supraorbital ridges palpable) or face (mentum or chin)?

What is the station? The station is the relationship in centimetres between the dominator as above and the ischial spine of the pelvis and is measured in centimetres above or below the spines – thus the depth of the presenting part is low when the tip of the presenting part is 2 or 3 cm below the spines?

What is the station? The station is the relationship in centimetres between the dominator as above and the ischial spine of the pelvis and is measured in centimetres above or below the spines – thus the depth of the presenting part is low when the tip of the presenting part is 2 or 3 cm below the spines?

Investigations in obstetrics and gynaecology

Bacteriological and virus tests

Bacteriological and virus tests used in gynaecology and obstetrics include the following:

Swabs from the throat, endocervix, vagina, urethra and rectum may be needed for sexually transmitted diseases (see Ch. 21 for more detail).

Swabs from the throat, endocervix, vagina, urethra and rectum may be needed for sexually transmitted diseases (see Ch. 21 for more detail).

Cervical scrape brush or liquid cytology samples for human papilloma virus.

Cervical scrape brush or liquid cytology samples for human papilloma virus.

Serum tests for toxoplasma, rubella, cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex (TORCH) detect antibodies from previous infections and may be protective of a future pregnancy.

Serum tests for toxoplasma, rubella, cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex (TORCH) detect antibodies from previous infections and may be protective of a future pregnancy.

Imaging

Hysterosalpingography

The preferred contemporary technique to image the uterine cavity and fallopian tubes is hysterosonography (hysterosalpingo contrast sonography, HyCoSy), rather than X-ray hysterosalpingography, in which the flow of saline or galactose microparticles through the tubes and uterus is visualized with a vaginal ultrasound probe, thereby avoiding exposure to radiation (Fig. 4.14).

Ultrasound

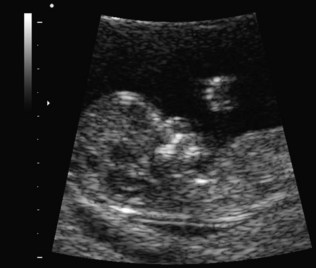

Transabdominal ultrasound enables a wide field of view, greater depth of penetration and transducer movement. Transvaginal ultrasound, with higher frequency transducers, gives increased resolution and diagnostic power but over a more limited area. More recently, 3-D scanners have been introduced, and these give improved image quality (Fig. 4.15).

In obstetrics, the integrity, location and the number of gestation sacs can be viewed in early pregnancy. By 11-13 weeks, mono- or dichorionicity, nuchal translucency, nasal bone development and gross fetal abnormality can be detected (Fig. 4.16). Changes in the cervix can be measured, giving an indication of possible late miscarriage or early premature labour. Anatomical anomaly scanning at 18-20 weeks is performed, particularly of the fetal heart and head and to detect functional activity. By 24 weeks, uterine and placental blood flow can be assessed, as can blood flow through fetal arteries.

Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging

Computed tomography (CT) scanning has proved less useful in gynaecology than was originally anticipated and is now used mainly for staging and follow-up of malignancies. Magnetic resonance imaging, where available, is a better option (see Fig. 4.9). It does not use ionizing radiation and is particularly good at staging gynaecological malignancies.

Endometrial sampling (biopsy)

Sampling of the endometrium is often diagnostically useful (Fig. 4.17). Formerly, this was performed by a dilatation of the cervix and curettage (D&C) to obtain histological material from the cavity of the uterus. Dilatation of the cervix is very painful and requires general anaesthesia. The definitive assessment is now usually by hysteroscopy and directed biopsy. With current miniature fibreoptic systems, this can be done under local analgesia in an outpatient setting.

Hysteroscopy

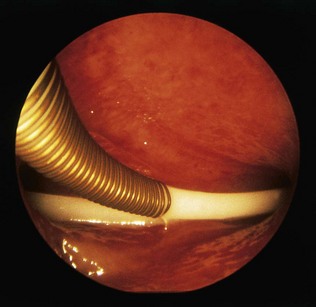

In this technique, the cavity of the uterus is viewed using small-diameter fibreoptic telescopes and cameras (Fig. 4.18). Diagnostic hysteroscopy using a 4-mm hysteroscope can be performed as both an inpatient and an outpatient procedure for disorders such as abnormal bleeding, subfertility and recurrent miscarriage. This technique can also be adapted with larger hysteroscopes to be used operatively for the resection of uterine adhesions, polyps, septae, submucous fibroids (Fig. 4.19) and endometrium.

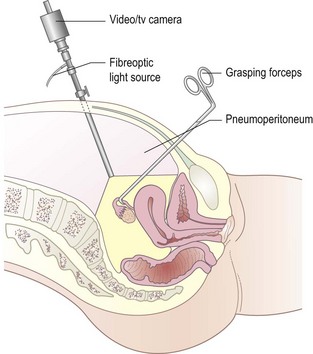

Laparoscopy

Visualization of the pelvic and abdominal viscera is particularly valuable if it can be done without a major injury to the abdominal wall (Fig. 4.20). The abdomen is inflated with carbon dioxide under general or local anaesthesia, so that the anterior abdominal wall is lifted away from the viscera, allowing inspection of the abdominal and pelvic contents using a fibreoptic telescope illuminated by a light source remote from the patient. Laparoscopy may be useful diagnostically (e.g. in the investigation of pelvic pain or infertility) and therapeutically (e.g. sterilization procedures, ectopic pregnancy).

Tests of fetal wellbeing

Biochemical tests

Biological tests

Amniocentesis

Samples of amniotic fluid may be used for the following:

Chromosome analysis: amniotic fluid is sampled at 13-18 weeks’ gestation, and is currently safer than chorion biopsy. The amount of desquamated fetal cells obtained is much smaller than from chorion biopsy, and cell culture is necessary, so chromosomal analysis is not immediately possible. However, rapid preliminary results can be obtained using the fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) technique (Fig. 4.21). This test is mostly used for prenatal diagnosis of Down’s syndrome and other chromosomal abnormalities.

Chromosome analysis: amniotic fluid is sampled at 13-18 weeks’ gestation, and is currently safer than chorion biopsy. The amount of desquamated fetal cells obtained is much smaller than from chorion biopsy, and cell culture is necessary, so chromosomal analysis is not immediately possible. However, rapid preliminary results can be obtained using the fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) technique (Fig. 4.21). This test is mostly used for prenatal diagnosis of Down’s syndrome and other chromosomal abnormalities.

DNA analysis: fetal cells obtained by amniocentesis, CVS or cordocentesis (see below) can be used for DNA analysis of nuclear chromatin in order to test directly for a number of genetically determined diseases in families known to be at risk. DNA testing and chromosomal studies should only be carried out with fully informed parental consent, and with the help of a genetic counselling service.

DNA analysis: fetal cells obtained by amniocentesis, CVS or cordocentesis (see below) can be used for DNA analysis of nuclear chromatin in order to test directly for a number of genetically determined diseases in families known to be at risk. DNA testing and chromosomal studies should only be carried out with fully informed parental consent, and with the help of a genetic counselling service.

Cordocentesis: in this procedure, a needle is inserted through the abdominal wall and into the amniotic sac to obtain fetal blood from the placental insertion of the cord. It is used in special centres when chromosomal abnormality, haemophilia, haemoglobinopathies, inborn errors of metabolism, fetal viral infections or fetal anaemia are suspected. Although the procedure carries more risk than amniocentesis, it is less traumatic than fetoscopy (which views the amniotic sac contents directly) while still permitting rapid diagnosis.

Cordocentesis: in this procedure, a needle is inserted through the abdominal wall and into the amniotic sac to obtain fetal blood from the placental insertion of the cord. It is used in special centres when chromosomal abnormality, haemophilia, haemoglobinopathies, inborn errors of metabolism, fetal viral infections or fetal anaemia are suspected. Although the procedure carries more risk than amniocentesis, it is less traumatic than fetoscopy (which views the amniotic sac contents directly) while still permitting rapid diagnosis.

Biophysical tests

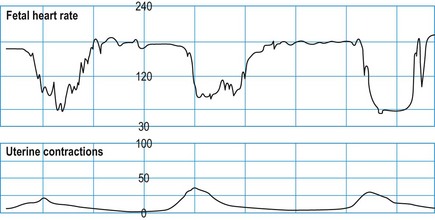

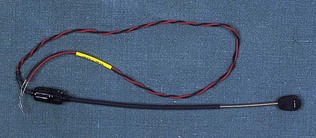

Cardiotocography (CTG)

Assessment of the fetal heart rate and its variation with fetal and uterine activity can be recorded antenatally or in labour with ultrasound using the Doppler principle (Figs 4.22 and 4.23). A pressure transducer is attached to the abdominal wall so that variations in uterine activity can be matched with the ultrasound recordings. In labour, once the membranes rupture, a more accurate recording of the fetal heart rate can be achieved by an electrode attached to the fetal scalp (Fig. 4.24). The recording is triggered by the fetal electrocardiogram.