Chapter 15 Skin Lightening Agents

INTRODUCTION

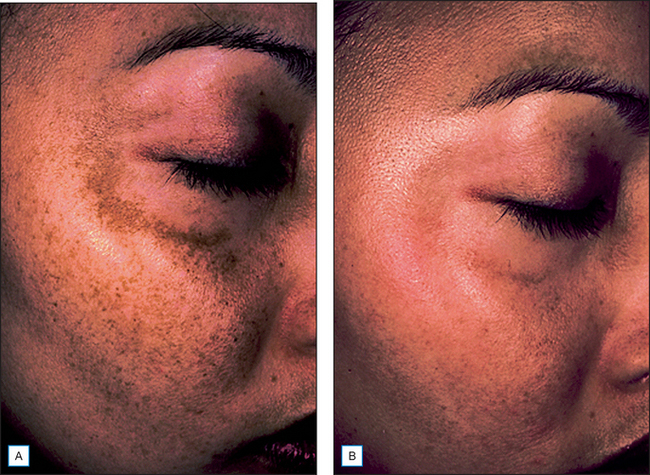

Hyperpigmentation is a common skin problem that is particularly prevalent in middle-aged and elderly individuals. It is cosmetically important and can greatly detract from both appearance and quality of life, particularly in cultures where smooth skin is valued as a sign of health or in cultures that are beauty conscious. Hyperpigmented skin lesions may be postinflammatory as a sequel to acne, trauma, chemical peels, or laser therapy. Exogenous causes, particularly ultraviolet (UV) light exposure, are a common factor in pigmentary abnormalities such as melasma, solar lentigines, and ephelides (Fig. 15.1). Exposure to certain drugs and chemicals as well as the existence of certain disease states can result in hyperpigmentation (Box 15.1).

SKIN LIGHTENING COSMECEUTICALS

Multiple depigmenting cosmeceuticals are currently available, although published clinical evidence to support their effectiveness is lacking. These skin lightening compounds work by removing undesired pigment by acting at one or more steps in the pigmentation process (Box 15.2). Since tyrosinase is the rate-limiting enzyme for melanin biosynthesis, many of the cosmeceuticals for skin lightening exert their effect on this enzyme.

Box 15.2 Depigmenting agents and reported effect on the melanin synthetic pathway

Modified from Briganti S, Camera E, Picardo M 2003 Chemical and instrumental approaches to treat hyperpigmentation. Pigment Cell Research 16:1–11.

• Hydroquinone

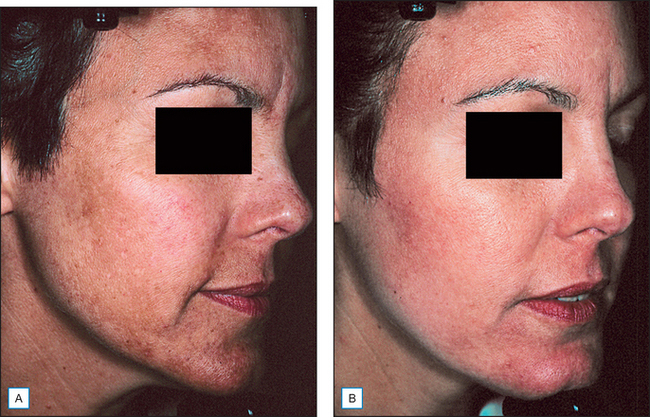

For many years, the phenolic compound hydroquinone has been the most widely and successfully used skin lightening agent for the treatment of melasma, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and other disorders of hyperpigmentation (Fig. 15.2). Hydroquinone occurs naturally in many plants as well as in coffee, tea, beer, and wine. Hydroquinone depigments skin by inhibiting the conversion of tyrosine to melanin. It has been shown to decrease tyrosinase activity by 90%. It may also inhibit DNA and RNA synthesis, as well as degrade melanosomes.

• Natural cosmeceuticals for dyspigmentation

Increasing interest in the use of natural actives, as well as the need to find an alternative to hydroquinone, has led to research on a variety of dyspigmentation treatment cosmeceuticals derived from natural ingredients (Box 15.3).

KOJIC ACID

Kojic acid is used in concentrations between 1 and 4% and is often more effective in combination with other ingredients (Box 15.4). Kojic acid has been reported to have a high sensitizing potential and may cause irritant contact dermatitis. However, it is useful in patients who cannot tolerate hydroquinone and studies show it may be combined with a topical corticosteroid to reduce irritation. Skin lightening products that contain kojic acid are typically used twice per day for 1 or 2 months or until the desired effect is achieved.

LICORICE EXTRACT—GLABRIDIN

Licorice extract is obtained from the root of Glycyrrhiza glabra linneva. Its main active ingredient is 10–40% glabridin. Glabridin offers 50% inhibition of tyrosinase activity with no attendant cytotoxicity and has been shown to be 16 times more efficacious than hydroquinone.

The combination of licorice extract with other ingredients yields good skin lightening responses (Box 15.5). New formulations containing licorice extract are under development for the treatment of dermal melasma.

VITAMIN C

Topical vitamin C products can be derived from such natural sources as fruits and vegetables, as discussed in Chapter 8, which is solely devoted to vitamin C. Vitamin C interferes with pigment production at various oxidative steps of melanin synthesis by interacting with copper ions at the tyrosinase active site and reducing dopaquinone. A stable derivative, magnesium L-ascorbic acid-2-phosphate (MAP), has been shown to lighten dyspigmentation.

MELATONIN

Melatonin is a hormone that is secreted by the pineal gland in response to sunlight. In addition to its effects on diurnal rhythms in mammals, it has been shown in vitro to inhibit melanogenesis in a dose-related manner. It does affect tyrosinase activity, suggesting that its effect occurs more proximally in the melanogenesis pathway. It has been shown to inhibit cyclic AMP-driven processes in pigment cells. The concentration needed for effective cosmeceutical skin lightening in human skin has not yet been established. It has been shown to have anti-inflammatory activity at a dosage of 0.6 mg/cm2.

GLYCOLIC ACID

Glycolic acid, an alpha-hydroxy acid derived from sugarcane, is an important cosmeceutical (discussed in detail in Chapter 16) that has skin lightening effects. At low concentrations, glycolic acid has an epidermal discohesive effect, which results in more rapid desquamation of pigmented keratinocytes. Like retinoids, glycolic acid shortens the cell cycle so that pigment is lost more rapidly. At higher concentrations, glycolic acid results in epidermolysis. Several studies have shown that the removal of superficial layers of epidermis with glycolic acid peels at concentrations of 30–70% can enhance the penetration of other topical skin lighteners such as hydroquinone.

• Other skin lightening products

Emblica, a compound isolated from Phyllanthus emblica fruits, is native to tropical southeastern Asia. The compound, a chelator for iron and copper, reduces UV-induced skin pigmentation at a 1% concentration and has a presumed effect on tyrosinase inhibition and expression.

Emblica, a compound isolated from Phyllanthus emblica fruits, is native to tropical southeastern Asia. The compound, a chelator for iron and copper, reduces UV-induced skin pigmentation at a 1% concentration and has a presumed effect on tyrosinase inhibition and expression.

Unsaturated fatty acids, such as oleic and linoleic acid, suppress pigmentation in vitro. Linoleic acid in vivo shows a skin lightening effect on UVB-induced pigmentation without toxic melanocyte effects.

Unsaturated fatty acids, such as oleic and linoleic acid, suppress pigmentation in vitro. Linoleic acid in vivo shows a skin lightening effect on UVB-induced pigmentation without toxic melanocyte effects.

An extract from the Chilean snail of the species Helix aspersa Müller has been used with success in the treatment of melasma and hyperpigmentation.

An extract from the Chilean snail of the species Helix aspersa Müller has been used with success in the treatment of melasma and hyperpigmentation.

Tyrostat, an extract of a plant native to Canada’s northern Prairie region, acts by inhibiting melanin synthesis.

Tyrostat, an extract of a plant native to Canada’s northern Prairie region, acts by inhibiting melanin synthesis.

RETINOIDS AND RETINOID COMBINATION THERAPY

Tretinoin is included in a triple combination dyspigmentation formulation currently approved for the treatment of melasma, as well as in several prescription acne and antiaging products in concentrations of 0.04–0.1%. Retinol is sold in OTC formulations and is less effective for the treatment of dyspigmentation and less irritating than tretinoin. Retinol 0.15% is an ingredient with 4% hydroquinone and UVA and UVB sunscreens in a cream that is used to treat disorders of hyperpigmentation. Other products include UVA and UVB sunscreens in their formulations.

SUMMARY

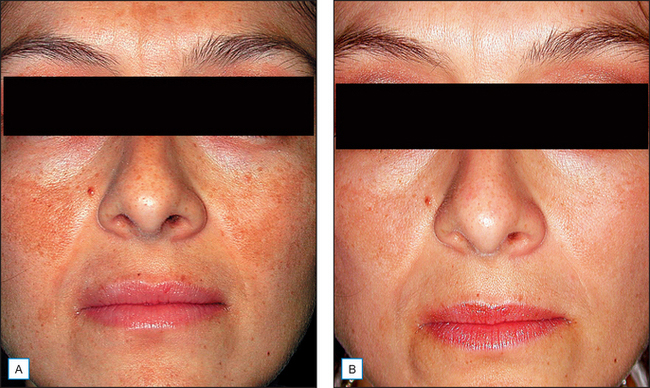

As the population ages, dyspigmentation due to photoaging will be more common. Hyperpigmentation from other causes, such as melasma and postinflammatory conditions, are also of increasing concern as patients realize that the unsightly brown discoloration can be improved with dermatologic treatment (Fig. 15.3).

Adebajo SB. An epidemiological survey of the use of cosmetic skin lightening cosmetics among traders in Lagos, Nigeria. West African Journal of Medicine. 2002;21:51–55.

Baumann L. Depigmenting agents. In: Day DJ, editor. Understanding hyperpigmentation. What you need to know. Continuing Medical Education monograph. Aurora, CO: Intellyst Medical Communications, 2004.

Briganti S, Camera E, Picardo M. Chemical and instrumental approaches to treat hyperpigmentation. Pigment Cell Research. 2003;16:1–11.

Cameli N, Marmo W, Gaeta A, Calderini G, Picardo M. Evaluation of clinical efficacy of a mixture of depigmenting agents. Pigment Cell Research. 2001;14:406.

Draelos ZD. Several active naturals aid in the prevention of photoaging. Highlights of a symposium: the role of natural ingredients in dermatology. Skin and Allergy News Supplement. 2004 January:4.

Guevara IL, Pandya AG. Safety and efficacy of a 4% hydroquinone combined with 10% glycolic acid, antioxidants, and sunscreen in the treatment of melasma. International Journal of Dermatology. 2003;42:966–972.

Hakozaki T, Minwalla L, Zhuang J, et al. The effect of niacinamide on reducing cutaneous pigmentation and suppression of melanosome transfer. British Journal of Dermatology. 2002;147:20–31.

Holloway VL. Ethnic cosmetic products. Dermatologic Clinics. 2003;21:743–749.

Jones K, Hughes J, Hong M, Jia Q, Orndorff S. Modulation of melanogenesis by aloesin: a competitive inhibitor of tyrosinase. Pigment Cell Research. 2002;15:335–340.

Kligman AM, Willis I. A new formula for depigmenting human skin. Archives of Dermatology. 1975;111:40–48.

Kollias N, Wallo W, Pote J, et al 2003 Documentation of changes in cutaneous pigmentation incorporating advances in imaging technology. Scientific Poster Presented at American Academy of Dermatology 61st Annual Meeting, San Francisco, California, March 21–26

Lim JT. Treatment of melasma using kojic acid in a gel containing hydroquinone and glycolic acid. Dermatologic Surgery. 1999;25:282–284.

Pérez-Bernal E, Muñoz-Pérez MA, Camacho F. Management of facial hyperpigmentation. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 2000;1:261-268.

Piamphongsat T. Treatment of melasma: a review with personal experience. International Journal of Dermatology. 1998;37:897–903.

Rendon MI. Melasma and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. Cosmetic Dermatology. 2003;16:9–17.

Sarkar R, Bhalla M, Kanwar AJ. A comparative study of 20% azelaic acid cream monotherapy versus sequential therapy in the treatment of melasma in dark skinned patients. Dermatology. 2002;205:249–254.

Seiberg M, Paine C, Sharlow E, et al. Inhibition of melanosome transfer results in skin lightening. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2000;115:162–167.