Skin disorders

The newborn

Common naevi and rashes in the newborn period are described under the examination of the newborn infant (see Ch. 9). Some less common skin conditions presenting in the newborn period are described in this chapter.

Bullous impetigo

This is an uncommon but potentially serious blistering form of impetigo, the most superficial form of bacterial infection, seen particularly in the newborn (Fig. 24.1). It is most often caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Treatment is with systemic antibiotics, e.g. penicillinase-resistant penicillin (see also Ch. 14).

Melanocytic naevi (moles)

Congenital moles occur in up to 3% of neonates and any that are present are usually small. Congenital pigmented naevi involving extensive areas of skin (i.e. naevi >9 cm in diameter) are rare but disfiguring (Fig. 24.2) and carry a 4–6% lifetime risk of subsequent malignant melanoma. They require prompt referral to a paediatric dermatologist and plastic surgeon to assess the feasibility of removal.

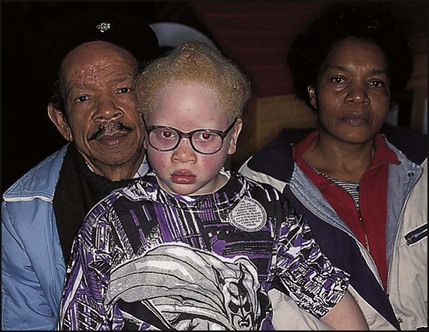

Albinism

This is due to a defect in biosynthesis and distribution of melanin. The albinism may be oculocutaneous, ocular or partial, depending on the distribution of depigmentation in the skin and eye (Fig. 24.3). The lack of pigment in the iris, retina, eyelids and eyebrows results in failure to develop a fixation reflex. There is pendular nystagmus and photophobia, which causes constant frowning. Correction of refractive errors and tinted lenses may be helpful. In a few children, the fitting of tinted contact lenses from early infancy allows the development of normal fixation. The disorder is an important cause of severe visual impairment. The pale skin is prone to sunburn and skin cancer. In sunlight, a hat should be worn and high factor barrier cream applied to the skin.

Epidermolysis bullosa

This is a rare group of genetic conditions with many types, characterised by blistering of the skin and mucous membranes. Autosomal dominant variants tend to be milder; autosomal recessive variants may be severe and even fatal. Blisters occur spontaneously or follow minor trauma (Fig. 24.4). They need to be differentiated from scalds. Management is directed to avoiding injury from even minor skin trauma and treating secondary infection. In the severe forms, the fingers and toes may become fused, and contractures of the limbs develop from repeated blistering and healing. Mucous membrane involvement may result in oral ulceration and stenosis from oesophageal erosions. Management, including maintenance of adequate nutrition, should be by a multidisciplinary team including a paediatric dermatologist, paediatrician, plastic surgeon and dietician.

Collodion baby

This is a rare manifestation of the inherited ichthyoses, a group of conditions in which the skin is dry and scaly. Infants are born with a taut parchment-like or collodion-like membrane (Fig. 24.5). Emollients are usually applied to moisturise and soften the skin. The membrane becomes fissured and separates within a few weeks, usually leaving either ichthyotic or less commonly, normal skin.

Rashes of infancy

Napkin rashes

Napkin rashes are common, although irritant reactions are much less of a problem with the widespread use of disposable nappies, as they are more absorbent. Some causes are listed in Box 24.1. Irritant dermatitis, the most common napkin rash, may occur if nappies are not changed frequently enough or if the infant has diarrhoea. However, irritant dermatitis can occur even when the napkin area is cleaned regularly. The rash is due to the irritant effect of urine on the skin of susceptible infants. Urea-splitting organisms in faeces increase the alkalinity and likelihood of a rash.

Candida infection may cause and often complicates napkin rashes. The rash is erythematous, includes the skin flexures and there may be satellite lesions (Fig. 24.6). Treatment is with a topical antifungal agent.

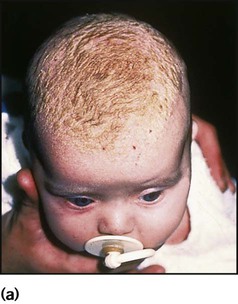

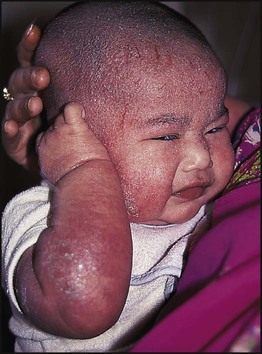

Infantile seborrhoeic dermatitis

This eruption of unknown cause presents in the first 2 months of life. It starts on the scalp as an erythematous scaly eruption. The scales form a thick yellow adherent layer, commonly called cradle cap (Fig. 24.7a). The scaly rash may spread to the face, behind the ears and then extend to the flexures and napkin area (Fig. 24.7b). In contrast to atopic eczema, it is not itchy and the child is unperturbed by it. However, it is associated with an increased risk of subsequently developing atopic eczema. Mild cases will resolve with emollients. The scales on the scalp can be cleared with an ointment containing low-concentration sulphur and salicylic acid applied to the scalp daily for a few hours and then washed off. Widespread body eruption will clear with a mild topical corticosteroid, either alone or mixed with an antibacterial and antifungal agent if appropriate.

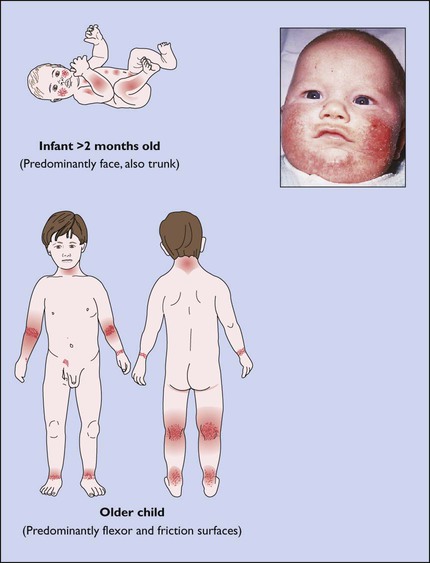

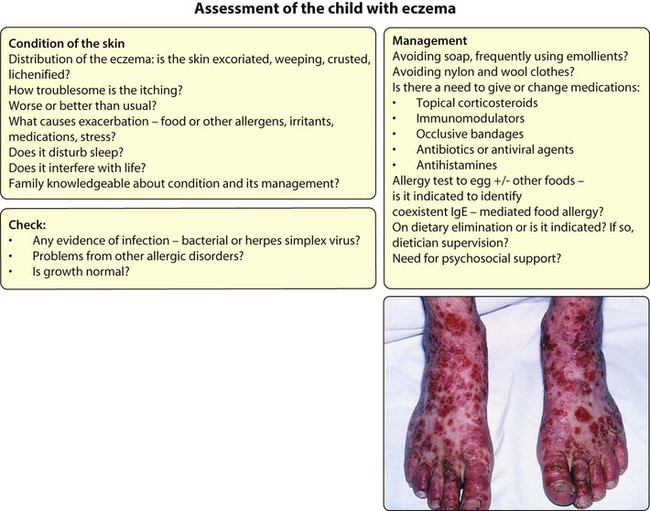

Atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis)

Clinical features

Rashes may itch in many conditions (Box 24.2), but in atopic eczema, itching (pruritus) is the main symptom at all ages and this results in scratching and exacerbation of the rash (Fig. 24.8). The excoriated areas become erythematous, weeping and crusted. Distribution of the eruption tends to change with age, as indicated in Figure 24.9.

Atopic skin is usually dry, and prolonged scratching and rubbing of the skin may lead to lichenification, in which there is accentuation of the normal skin markings (Fig. 24.10).

Complications

Causes of exacerbations of eczema are listed in Box 24.3. However, flare-ups are common, often for no obvious reason. Eczematous skin can readily become infected, usually with Staphylococcus or Streptococcus (Fig. 24.11). Inflammation increases the avidity of skin for Staph. aureus and reduces the expression of antimicrobial peptides, which are needed to control microbial infections. Staph. aureus thrives on atopic skin and releases superantigens which seem to maintain and worsen eczema. Herpes simplex virus infection, although less frequent, is potentially very serious as it can spread rapidly on atopic skin, causing an extensive vesicular reaction, eczema herpeticum (see Ch. 14). Regional lymphadenopathy is common and often marked in active eczema; it usually resolves when the skin improves.

Infections and infestations

Bullous impetigo has been considered earlier in this chapter and acute bacterial and viral infections of the skin are considered in Chapter 14.

Viral infections

Viral warts

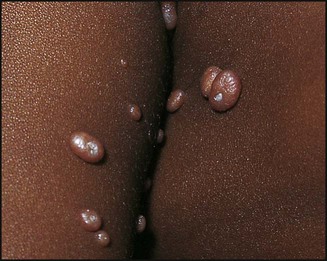

Molluscum contagiosum

This is caused by a poxvirus. The lesions are small, skin-coloured, pearly papules with central umbilication (Fig. 24.12). They may be single but are usually multiple. Lesions are often widespread but tend to disappear spontaneously within a year. If necessary, a topical antibacterial can be applied to prevent or treat secondary bacterial infection, and cryotherapy (2–3 s only) can be used in older children, away from the face, to hasten the disappearance of more chronic lesions.

Fungal infections

Ringworm

Dermatophyte fungi invade dead keratinous structures, such as the horny layer of skin, nails and hair. The term ‘ringworm’ is used because of the often ringed (annular) appearance of skin lesions. A severe inflammatory pustular ringworm patch is called a kerion (Fig. 24.13).

Parasitic infestations

Scabies

In older children, burrows, papules and vesicles involve the skin between the fingers and toes, axillae, flexor aspects of the wrists, belt line and around the nipples, penis and buttocks. In infants and young children, the distribution often includes the palms (Fig. 24.14), soles and trunk. The presence of lesions on the soles can be helpful in making the diagnosis. The head, neck and face can be involved in babies but is uncommon.

Pediculosis

Pediculosis capitis (head lice infestation) is the most common form of lice infestation in children. It is widespread and troublesome among primary school children. Presentation may be itching of the scalp and nape or from identifying live lice on the scalp or nits (empty egg cases) on hairs (Fig. 24.15). Louse eggs are cemented to hair close to the scalp and the nits (small whitish oval capsules) remain attached to the hair shaft as the hair grows. There may be secondary bacterial infection, often over the nape of the neck, leading to a misdiagnosis of impetigo. Sub-occipital lymphadenopathy is common. Once infestation is confirmed by finding live lice, treatment is by applying a solution of 0.5% malathion to the hair and leaving it on overnight. The hair is then shampooed and the lice and nits removed with a fine-tooth comb. Treatment should be repeated a week later. Permethrin (1%) as a cream rinse would be an alternative application; it is left on for 10 min only. Flammability of alcohol-based lotions should be noted. Wet combing to remove live lice (bug-busting) every 3–4 days for at least 2 weeks is a useful and safe physical treatment, particularly when parents treat with enthusiasm.

Other childhood skin disorders

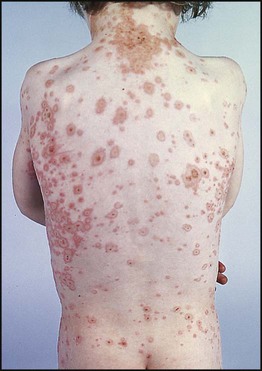

Psoriasis

This familial disorder rarely presents before the age of 2 years. The guttate type (Fig. 24.16) is common in children and often follows a streptococcal or viral sore throat or ear infection. Lesions are small, raindrop-like, round or oval erythematous scaly patches on the trunk and upper limbs, and an attack usually resolves over 3–4 months. However, most get a recurrence of psoriasis within the next 3–5 years. Chronic psoriasis with plaques or annular lesions is less common. Fine pitting of the nails may be seen in chronic disease but is unusual in children. Treatment for guttate psoriasis is with bland ointments. Coal tar preparations are useful for plaque psoriasis and scalp involvement. Dithranol preparations are very effective in resistant plaque psoriasis. Calcipotriol, a vitamin D analogue, which does not stain the skin, can also be useful for plaque psoriasis in those over 6 years old. Occasionally, children with chronic psoriasis develop psoriatic arthritis. Chronic psoriasis may have a considerable effect on quality of life. The Psoriasis Association can be helpful in offering support and advice.

Alopecia areata

This is a common form of hair loss in children and, understandably, a cause of much family distress. Hairless, single or multiple non-inflamed smooth areas of skin, usually over the scalp, are present (Fig. 24.17); remnants of broken-off hairs, visible as ‘exclamation mark’ hairs may be seen at the edge of active patches of hair fall. The more extensive the hair loss, the poorer the prognosis, but regrowth often occurs within 6–12 months in localised hair loss. Prognosis should be more guarded in children with atopic disorders.

Granuloma annulare

Lesions are typically ringed (annular) with a raised flesh-coloured non-scaling edge (unlike ringworm) (Fig. 24.18). They may occur anywhere but usually over bony prominences, especially over hands and feet. Lesions may be single or multiple, are usually 1–3 cm in diameter, and tend to disappear spontaneously but may take years to do so. There is also a subcutaneous form.

Rashes and systemic disease

Skin rashes may be a sign of systemic disease. Examples are:

• Facial rash in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or dermatomyositis

• Purpura over the buttocks, lower limbs and elbows in Henoch–Schönlein purpura

• Erythema nodosum (Fig. 24.19, Box 24.4) and erythema multiforme (Fig. 24.20, Box 24.5); both can be associated with a systemic disorder, but often no cause is identified

• Stevens–Johnson syndrome, a severe bullous form of erythema multiforme also involving the mucous membranes (Fig. 24.21). The eye involvement may include conjunctivitis, corneal ulceration and uveitis, and ophthalmological assessment is required. It may be caused by drug sensitivity or infection, with morbidity and sometimes even mortality from infection, toxaemia or renal damage