90 Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

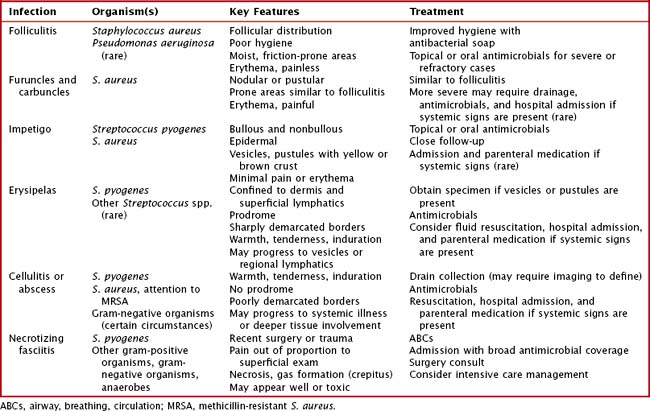

For clinicians, it is essential to quickly recognize these infections, assess and evaluate their depth and rate of spread, and begin appropriate antimicrobial treatment (Table 90-1).

Clinical Presentation

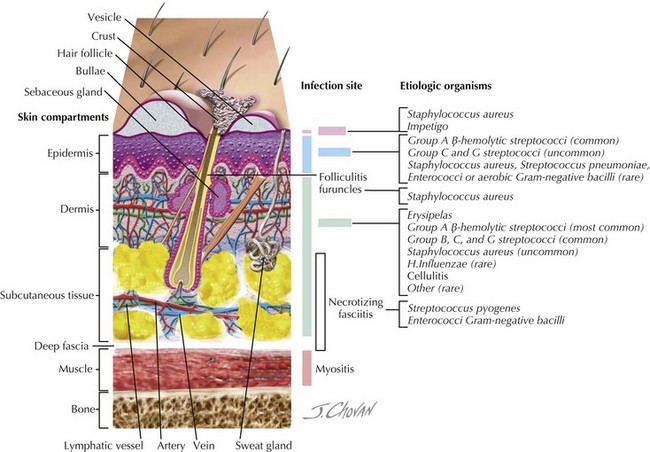

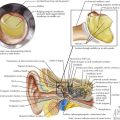

Nearly all skin and soft tissue infections are characterized by a varying degree of erythema, pain or tenderness, and warmth. For clinicians, after it has been established that there is a likely bacterial infection, the next steps are to determine the depth and degree of the infection and its rate of spread (Figure 90-1).

Folliculitis

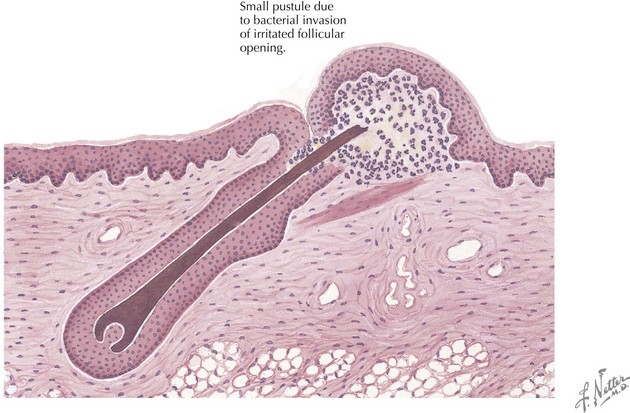

Folliculitis is a superficial pustule or local area of inflammation surrounding a hair follicle (Figure 90-2). It can be solitary, but it can also occur in clusters. The most commonly affected areas include those of high moisture and friction, such as the axillae and inguinal creases, but the scalp, extremities, and perioral and paranasal areas are also commonly affected. Poor hygiene and a humid environment are risk factors, as are active drainage from more severe nearby wounds. S. aureus is the predominant organism, with the exception of folliculitis that occurs shortly after immersion in a poorly maintained pool or hot tub, in which case Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the likely organism. Folliculitis is not usually painful, but if progression to more significant infections takes place, pain can become significant.

Furuncles and Carbuncles

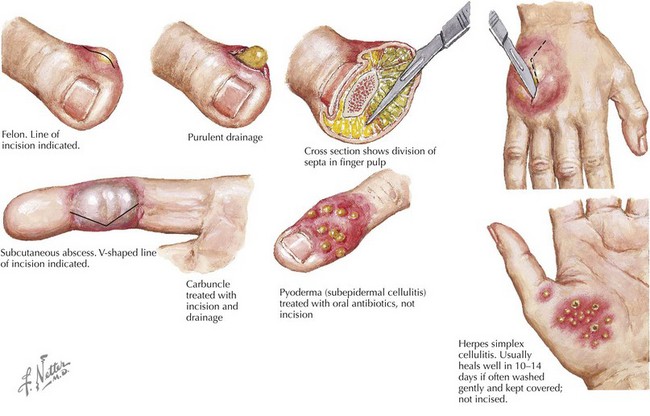

Furuncles (boils) and carbuncles are uncommon in childhood, with the notable exception of children with atopic dermatitis (Figure 90-3). This population, perhaps because of its higher rates of S. aureus (the primary causative organism) colonization, is at risk for these infections. Both of these infections can be sequelae of poorly managed folliculitis. A furuncle is an acute infection of the hair follicle, often accompanied by necrosis, that begins as a nodule and then progresses to a pustule. Common locations are the neck, face, axillae, groin, and buttocks, and risk factors are similar to those of folliculitis, with the addition of hyperhidrosis, anemia, and obesity. A carbuncle is a collection of confluent furuncles, often with multiple drainage points. They can be single or multiple, frequently appearing in crops in areas similar to furuncles. Both lesions are erythematous and can be painful, and occasionally, carbuncles can progress to the point where the patient develops constitutional symptoms and laboratory evidence of more severe infection.

Erysipelas

Erysipelas and cellulitis are skin infections that are both characterized by erythema, warmth, and pain (Figure 90-4). Erysipelas is the more superficial of the two infections, with invasion confined to the dermis and frequently the superficial lymphatics. S. pyogenes is the most common pathogen, but other Streptococcus spp. have been isolated. The bacteria are usually established as colonizers in the host’s nasopharynx and autoinoculated into a break in the patient’s skin. The skin lesions are often preceded by prodromal symptoms of fever, malaise, and chills up to 48 hours before the onset of lesions. Skin lesions begin as brightly erythematous, raised areas with sharply demarcated, potentially rapidly advancing borders. Warmth, local edema, and tenderness are nearly universally present, and less frequently, there are signs of lymphatic spread such as streaking and regional lymph node inflammation. Severe infection can lead to the formation of vesicles and skin necrosis.

Evaluation and Management

Moderate Infections

Obtaining a specimen, when possible, is very important because it has implications for both management and treatment. Not only will a culture of the material be useful for appropriate antimicrobial selection, but removal of fluid within a collection or abscess is an essential therapeutic step because the likelihood that such lesions would improve with antimicrobials alone is minimal. For many lesions (impetigo, carbuncles), drainage may be spontaneous or may be achieved with soaks and compresses. In other cases, incision and drainage may be required (Figure 90-5). If an abscess or collection is identified on examination, the procedure is straightforward. If a collection is not apparent but the clinician has a high index of suspicion based on history (abscesses in past, duration, fevers) or examination (location, size), imaging may be indicated. Optimal modalities vary largely with the location of the lesions: ultrasonography is most useful when the infection is confined to the superficial tissues of an extremity, computed tomography is frequently used when evaluating the head or neck, and magnetic resonance imaging is used when there is the question of bony involvement. When the infection is causing systemic signs and symptoms that require fluid resuscitation and more extensive incision and drainage, the clinician should consider the need for further evaluation, including laboratory testing (blood culture and complete blood count), intravenous antimicrobials, and hospital admission. Inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein may be used to monitor response to therapy in more severe infections. Blood cultures clearly do not have as high a yield as wound or lesion cultures, but their yield increases when signs of systemic illness are present.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Infectious Diseases. severe invasive group A streptococcal infections: a subject review. Pediatrics. 1998;101(1 Pt 1):136-140.

Fleisher GR, Ludwig S, Henretig FM, eds. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 5th ed, Philadelphia, 2005, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Hedrick J. Acute bacterial skin infections in pediatric medicine: current issues in presentation and treatment. Paediatr Drug. 2003;5(Suppl 1):35-46.

Oumeish I, Oumeish OY, Bataineh O. Acute bacterial skin infections in children. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18(6):667-678.

Zaoutis B, Chiang W: Comprehensive Pediatric Hospital Medicine, Philadelphia, 2007, Saunders.