Chapter 24 Skin

COMMON CLINICAL PROBLEMS FROM SKIN DISEASE

| Clinical sign | Pathological basis |

|---|---|

| Scaling | Parakeratosis |

| Erythema | Dilatation of skin vessels |

| Blisters | Separation of layers of the epidermis or epidermis from dermis |

| Bruising | Leakage of blood into dermis |

| Pigmentation |

NORMAL STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION

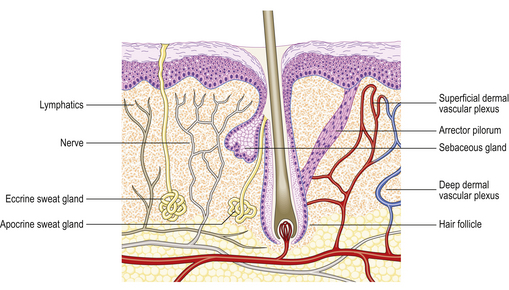

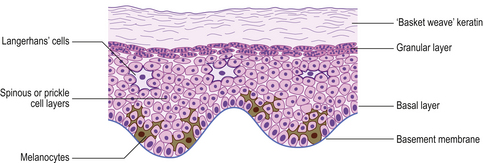

The two major layers of the skin—the superficial epidermis and deeper dermis—are derived from different embryonic components and retain a radically different morphology (Fig. 24.1). The epidermis is highly cellular, avascular, lacks nerves, sits on a basement membrane and shows marked vertical stratification (Fig. 24.2). It produces a complex mixture of proteins collectively termed keratin. A series of specialised adnexa extend from the epidermis into the dermis. The density of these adnexa varies from site to site on the body, as does the thickness of the epidermis and the structure of the keratin layer. This site-to-site variation means that the histological interpretation of diagnostic biopsies has to take into account the area of the body from which the biopsy was taken; what may constitute severe hyperkeratosis (excess keratin) on the forehead may be normal for the sole of the foot.

The dermis is relatively acellular and is recognisably divided into two zones: the upper zone comprises extensions of the dermis (dermal papillae) between the downward projecting rete ridges (‘pegs’) of the epidermis and is called the papillary dermis; beneath this zone is the reticular dermis. Both regions of the dermis contain blood and lymph vessels as well as nerves. The intervening connective tissue consists of the characteristic dermal proteins collagen and elastin, together with various glycosaminoglycans. These proteins and complex carbohydrates are secreted by the principal cells of the dermis, the fibroblasts. Although the proteins of the dermis appear to be arranged in a haphazard fashion when viewed in standard histological preparations, they are in fact arranged in specific patterns that are characteristic of different sites in the body; these patterns are the Langer’s lines. The significance of this knowledge is that if incisions are made in the skin along the long axis of the dermal collagen fibres then little permanent scarring will occur. If, however, incisions are made across the fibres and disrupt them, then in the effort to repair the damage scarring is bound to result. A considerable part of the surgeon’s skill relies on knowing the characteristic orientation of these fibres and in making incisions that generate the minimum risk of permanent scars. Scattered within the dermis and often clustered about blood vessels are the mast cells. The nerves of the dermis approach close to the epidermis and often end in specialised sensory structures such as Pacinian corpuscles. Similarly, the dermal blood vessels run close to the underside of the epidermis, although they are organised into two recognisable structures—the superficial and deep vascular plexuses.

Skin as a barrier

The other way in which the barrier is often breached is at the weak points where there are natural holes in the barrier, such as the sweat glands and hair ducts, and organisms may use these portals of entry.

Failure of the barrier (eczema and immersion)

Eczema/dermatitis

The word eczema comes from the Greek meaning to ‘bubble up’; this meaning conveys well the clinical development of the lesions. The word dermatitis is often used in an interchangeable manner, in particular when referring to the histopathological changes. The skin becomes reddened (erythematous) and tiny vesicles may develop (pompholyx); the surface develops scales, and cracking and bleeding can cause great discomfort (Fig. 24.3). The skin becomes tender and secondary infection may occur. The clinical pattern is very varied and there are several different types of eczema. Sometimes the variation is due to the cause of the eczema, such as contact with a toxic or allergenic material; sometimes the site of the lesion or the age of the patient is sufficient to make the disease a clinical entity. For example, chromate hypersensitivity causes eczema in cement workers and discoid/atopic eczema occurs in atopic individuals. Seborrhoeic eczema has a tendency to involve the scalp, face, axillae and groins. Whatever the cause, the underlying pathological processes are recognisably similar and can be seen as a stereotyped reaction pattern to a variety of different stimuli.

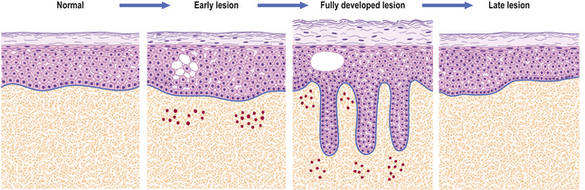

The earliest histological change in eczema is swelling within the epidermis (Fig. 24.4). This swelling is due to separation of the keratinocytes by fluid accumulating between them and this appearance is known as spongiosis. Later, there may be hyperkeratosis (an increase in the thickness of the stratum corneum) and parakeratosis (retention of nuclei in the stratum corneum), which give rise to the clinical scales. Various degrees of inflammation also give rise to the classical inflammatory signs and symptoms (Ch. 10). In severe cases the intercellular oedema can then join up to form foci of fluid within the epidermis, recognised clinically as blisters or vesicles (pompholyx) (Fig. 24.5).

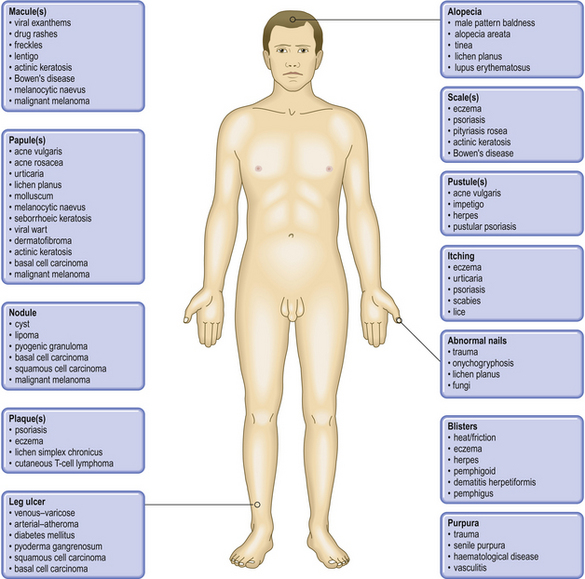

CLINICAL ASPECTS OF SKIN DISEASES

Incidence of skin diseases

Skin diseases, like all diseases, vary in their distribution according to a wide range of factors (Table 24.1), but they also vary markedly in the experience of particular doctors. A hospital dermatologist running a pigmented skin lesion clinic will see many melanomas in a year, depending on the population make-up of the catchment area and its size, whereas a general practitioner in the same area may expect to see only one every 2 years. A dermatologist will see only the difficult cases of acne and pityriasis rosea but a general practitioner will see many more straightforward ones. With these reservations in mind, skin diseases can be categorised according to their frequency:

| Variable | Associations |

|---|---|

| Age |

DISORDERS INVOLVING INFLAMMATORY and HAEMOPOIETIC CELLS

Many of the characteristics of inflammation (Ch. 10) were first observed and studied in the skin. The various phases and types of inflammation are characterised by a particular spectrum of cells that mediate the inflammatory response. Because the types of cell in a particular lesion are there in response to the initiating factor, a careful analysis of the composition of a particular lesion will significantly narrow down the differential diagnosis. Thus, cuffing of vessels by plasma cells would strongly suggest syphilis and the presence of granulomas with caseous centres would suggest tuberculosis.

Polymorph infiltrates

Some diseases, such as Sweet’s disease and pyoderma gangrenosum (skin lesions that may occur in association with various internal diseases such as chronic inflammatory bowel diseases; Ch. 15), show massive infiltration by polymorph neutrophils in the dermis.

In some cases, polymorphs are attracted by the deposition of auto-antibodies (Ch. 9) and in these cases the resulting damage often causes blistering. Antibodies to the basement membrane on which the epidermis sits and to proteins in the papillary dermis cause pemphigoid and dermatitis herpetiformis respectively (see below). The presence of one type of polymorph rather than another suggests different aetiological processes and dermatitis herpetiformis can sometimes be distinguished from bullous pemphigoid by the relative excess of neutrophil polymorphs in the former and eosinophil polymorphs in the latter. Eosinophil polymorphs are a frequent reflection of allergic diseases (such as eczema) and parasitic infestation.

Lymphocytic infiltrates

Any chronic inflammation of the skin will eventually come to be dominated by lymphocytes, but there are many skin conditions that are primarily due to lymphocyte accumulation and whose distinctive clinical character is due to the disposition and behaviour of these cells. The lymphocytes present in inflammation are usually of T-cell type and most commonly of CD4/helper phenotype.

Cutaneous lymphomas

Secondary deposits of systemic lymphomas and primary lymphomas may occur within the skin. Both are relatively rare. Any of the lymphomas and leukaemias that occur systemically (Ch. 22) can give secondary deposits in the skin, but usually only in advanced cases. The primary lymphomas include mycosis fungoides which is a T-cell lymphoma and which, as it develops, can spill over into the blood to give an associated T-cell leukaemia, called the Sézary syndrome.

Occasionally, skin lymphomas also result from B-cell lymphocytes.

INFECTIONS

The clinical appearance depends on:

There are two routes by which infection may arrive in the skin:

In practice, most infections arise via the latter route.

Another possible mechanism whereby infections can cause skin lesions is where the organism infects some other part of the body but produces a skin rash in which it is impossible to identify any organisms; this mechanism, for example, occurs in acute rheumatic fever and is similar to the effects on the heart also seen in this condition (Ch. 13). Staphylococcus can produce a toxin and give rise to a blistering disorder called the staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome.

Viral infections

Other herpes viruses are responsible for cold sores (HSV1) and for genital herpes (HSV2). The great problem with these kinds of herpetic infections is that they are infections for life.

Protozoal infections

Leishmaniasis is an infection caused by Leishmania tropica which is transmitted by sandflies. The organisms have developed a mechanism for subverting the body’s defences and can be found living in abundance within the host macrophages.

NON-INFECTIOUS INFLAMMATORY DISEASES

Urticaria

Histologically, the collagen bundles of the dermis are separated by the oedema and a sparse infiltrate of polymorphs, often including eosinophils and an increased numbers of mast cells. The most important mediator of this process is histamine but other substances such as kinins and various circulating globulins, mainly IgE, play a role (Ch. 10). Agents causing urticaria include:

Lupus erythematosus

Clinicopathological features

Clinically, LE is a multisystem disease which may present with symptoms associated with almost any organ; in practice, skin and renal (Ch. 21) involvement are among the commonest. In many cases the skin appears to be the only organ involved and the disease is then called discoid LE. The systemic variant may or may not involve the skin. However, the fact that the lesions in discoid and systemic cases are often indistinguishable, and the occurrence of serological abnormalities in systemic and some discoid cases, suggest that the relationship is close.

The skin lesions are initially erythematous, scaly and indurated and slowly progress to atrophic scarred patches, often with hyperpigmented edges in the older lesions. They are often symmetrical on the face in a butterfly distribution over the nose and cheeks, and on the scalp may be associated with a scarring alopecia. These features are explained by the histology, which shows a dilatation of superficial vessels with a dense accumulation of lymphocytes around them, leading to the observed erythema. The infiltrate also involves the dermo-epidermal interface and damages the melanocytes. The melanocytes lose their melanin to dermal macrophages in which the pigment accumulates, accounting for the hyperpigmentation in older lesions. The persistent junctional inflammation results in damage to hair follicles, with the formation of follicular plugs (tin-tacks) and eventually atrophy of hair follicles and the epidermis itself.

Psoriasis

Clinicopathological features

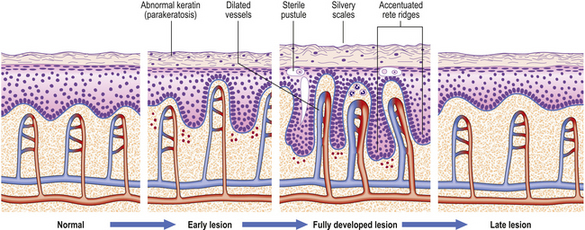

The lesions are commonest on the extensor surfaces (Fig. 24.6), such as the knees and elbows, and the first appearance may be in a site of trauma such as a surgical wound—a phenomenon known as the Koebner effect. The clinical lesions are termed plaques, meaning slightly palpable and elevated areas, often measuring over 50mm. The individual lesions are covered with a silvery scale and scraping the scale off reveals a series of small bleeding points (Auspitz’s sign).

Histologically (Fig. 24.7), the normal pattern of rete ridges becomes thickened (acanthotic) and the dermal papillae are covered only by a thin layer of epidermis two or three cells thick. This accounts for the bleeding points seen when the scale is scratched off. The progress of the epidermal cells through the epidermis is speeded up and maturation is incomplete. This is reflected in the accumulation of abnormal keratin with nuclear fragments (parakeratosis) in the form of the silvery scales. The maturation of the keratin is so disturbed that the normal granular layer of the epidermis is lost (Fig. 24.7). The erythema is caused by dilated vessels in the upper dermis and these can be seen to contain numerous polymorphs which migrate from the vessels into the epidermis, sometimes in sufficient numbers to form actual pustules. These sterile pustules may dominate the clinical picture in one variant of the disease (pustular psoriasis) and this presentation is often marked when the disease appears on the palms of the hands or soles of the feet.

Lichen planus

Lichen planus is a non-infectious inflammatory disease characterised by destruction of keratinocytes, probably mediated by interferon-gamma and tumour necrosis factor from T-cells in the dermal infiltrate. Usually there is no precipitating factor but some drug eruptions may be indistinguishable. It affects the skin, often the inner surfaces of the wrists (Fig. 24.8), and the mucosae, where it appears as a white lacy lesion. On the skin it presents as small, intensely itchy, polygonal, violaceous papules that may develop into blisters, particularly on the palms of the hands or soles of the feet. As the eruption heals, which it usually does spontaneously, it may leave behind hyper- or hypopigmented patches.

Clinicopathological features

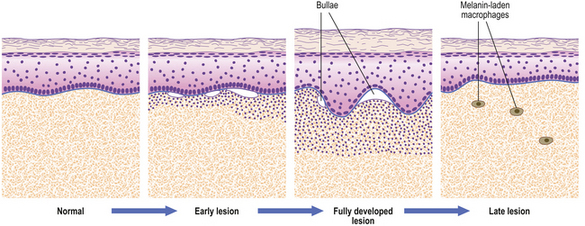

Histology reveals a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in a band-like distribution at the dermo-epidermal junction. The basal layer of the epidermis comes under lymphocytic attack and foci of degeneration, apoptosis and regeneration are seen; this eventually gives the epidermis a characteristic saw-tooth profile. Little splits also occur at the junction and, rarely, these may coalesce to form bullae (Fig. 24.9). Lichen planus constitutes the classical so-called lichenoid reaction. In contrast to psoriasis there is an increase in the granular layer; the scale is consequently different and presents as tiny white lines running over the papules. During the active phase of the eruption papules can be induced by minor trauma such as scratching. Treatment is with steroids, and in those cases in which a precipitating cause can be identified this can then be withdrawn.

EPIDERMAL CELLS

Normal structure and function

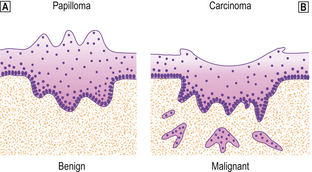

Although the epidermis is involved in the pathogenesis of numerous diseases, such as lichen planus or eczema, the main diseases of significance that involve the epidermis primarily are disorders of keratinisation (such as ichthyosis when the keratin layer is thickened due to gene mutations) and various neoplasms, both benign and malignant. The cellular layers of the epidermis are also the main site of viral infections, because viruses require living cells for their replication. The range of epidermal neoplasms that have been described is very wide, but the majority are rare and those described below are common or important clinical problems (Fig. 24.10).

Benign epidermal neoplasms and tumour-like conditions

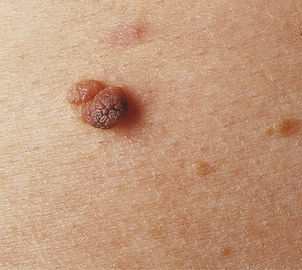

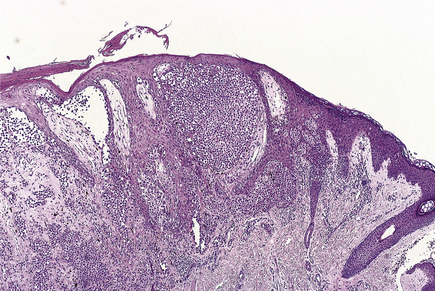

Seborrhoeic wart/keratosis (basal cell papilloma)

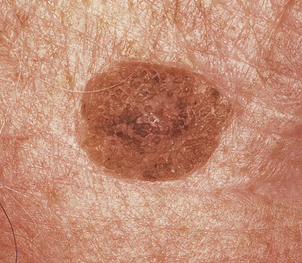

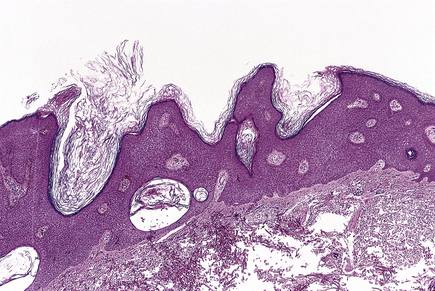

Seborrhoeic warts/keratoses are much more common in the elderly and, despite their name, have nothing to do with sebaceous glands. They are also called basal cell papillomas but seborrhoeic wart/keratosis is the preferred name to avoid confusion with the term basal cell carcinoma. They are dark, greasy-looking (hence ‘seborrhoeic’) nodules with an irregular surface (Fig. 24.11). They can occur on most parts of the skin surface and rarely turn malignant. Histologically they consist of a proliferation of cells with similar appearances to the basal cells in the epidermis (Fig. 24.12). They have a very convoluted surface with keratin tunnels extending deeply from the surface inwards (horn cysts). In some cases they may become inflamed, due to irritation or attempts by the body to remove the lesion (regression). Although they have little biological significance, they are often removed for cosmetic purposes or to exclude melanoma. In one very rare condition a sudden, widespread, pruritic crop of these lesions may be a sign of internal malignancy, usually in the gastrointestinal tract (the sign of Leser–Trélat).

Cysts

Various benign cysts occur in the skin, the commonest being:

They occur in the dermis and contain keratin, not sebum. The distinguishing feature is the nature of the cyst lining. In epidermal cysts, the lining is identical to normal epidermis. In sebaceous cysts, the lining is identical to the middle part of the hair follicle. Consequently, it is believed that epidermal cysts arise from the upper part of the hair follicle, where it is lined by normal epidermis, and that sebaceous cysts arise from the deeper part.

Malignant epidermal neoplasms

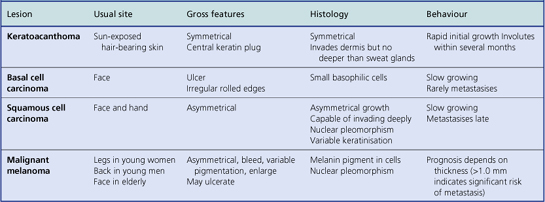

Malignant skin tumours are among the commonest neoplasms but only malignant melanomas account for a significant number of deaths. The main features are summarised in Table 24.2.

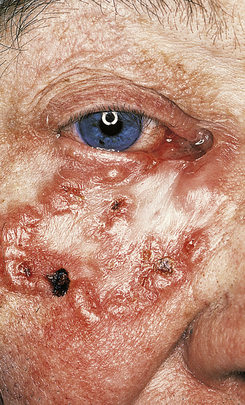

Basal cell carcinoma

Basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) are the commonest skin tumour and they are closely associated with chronic sunlight exposure. They are, therefore, most common on the face of elderly people. Clinically, they are often ulcerated irregular lesions, hence their common name of rodent ulcers, with a raised pearly border, often with tiny blood vessels visible on the border (Fig. 24.13).

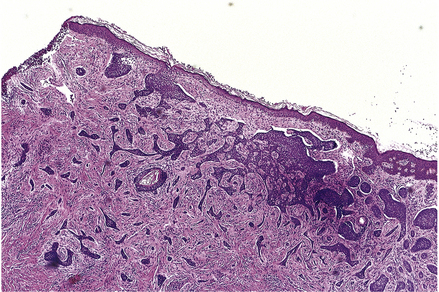

Histologically, they are formed of clumps of small cells surrounded by a rim of cells whose nuclei line up like a picket fence (palisading) (Fig. 24.14). Mitoses are frequent and ulceration is common. The cells are very similar in appearance to those of the normal basal layer of the epidermis; the tumours are believed to arise from this layer and from hair follicles.

Squamous cell carcinoma

Invasive squamous cell carcinomas are common and are aetiologically related to chronic sunlight exposure, immunosuppression or to chemical carcinogens such as arsenic, tar and machine oil. They also occur in the site of previous X-irradiation. They are much more common in the elderly on sun-exposed areas. Clinically, they may be roughened keratotic areas, papules, nodules, ulcers or horns (Fig. 24.15). They are difficult to distinguish from keratoacanthomas except by their behaviour.

Histologically, they are composed of disorganised keratinocytes with typical malignant cytology. They also show foci of keratinisation within the tumour and thus appear to echo the behaviour of the normal upper layers of the epidermis but in a disordered and malignant fashion.

Rarely, squamous cell carcinomas arise at the edge of chronic skin ulcers (Marjolin’s ulcer).

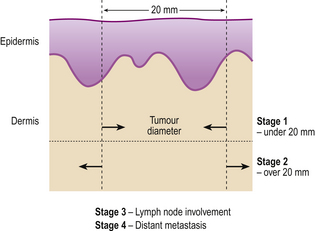

The staging of basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma is shown in Figure 24.16.

Blisters

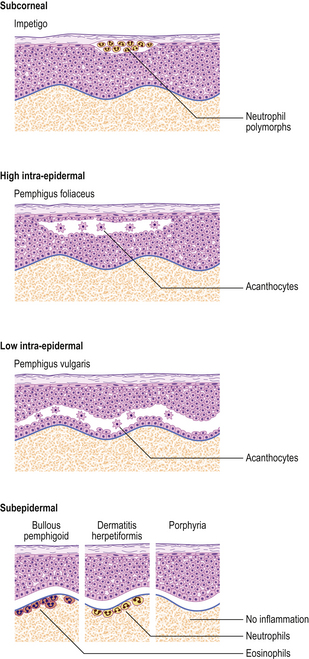

Blisters are fluid-filled spaces within the skin due to separation of two layers of tissue and the leakage of plasma into the space. When over 5mm they are called bullae, and under 5mm vesicles.

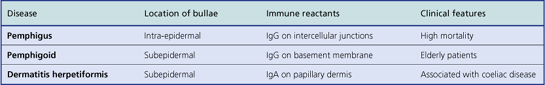

The most common forms of blister are thermal burns and friction blisters. The latter occur commonly on the foot, due to shearing forces set up within the skin as a result of poorly fitting footwear. Such blisters form at the dermo-epidermal junction but other blisters may form at any level within the skin and the precise site of blisters gives a very good clue as to their nature (Fig. 24.17). Many blisters form because an antibody attacks some skin component that has a discrete distribution within the skin and this attack causes separation at that point. Subsequent damage to the blister roof causes it to be shed; the barrier function is lost and secondary infection may ensue.

Fig. 24.17 Blistering conditions. Various diseases can have a blistering phase but in some the blister is the primary or only feature. The clinical presentation depends on the level in the skin at which the blisters form. The precise diagnosis often requires special diagnostic techniques such as immunofluorescence. (Porphyria is described in Ch. 7.)

There are several distinct mechanisms of blister formation:

With the help of immunofluorescence techniques, it is possible to diagnose these types histologically (Table 24.3).

Bullous pemphigoid

This disease is more common than pemphigus, although still rare, and occurs mainly in those aged over 60 years (Fig. 24.18). It is generally self-limiting but may be associated with a long period of pruritus, even after the blisters have healed. In this disease the split occurs at the dermo-epidermal junction and is due to circulating antibodies to the lamina lucida layer (immediately adjacent to the basal cells) of the epidermal basement membrane. Immunofluorescence reveals a linear deposition of antibody, generally IgG, along the basement membrane. The antigen–antibody complex causes the release of various complement factors which can also be demonstrated by immunofluorescence and the whole reaction causes degranulation of mast cells. This accounts not only for the pruritus but also for the characteristic presence of eosinophils, which are the common accompaniment of mast cell activation in any condition. Being deeper, the blisters are more persistent, although the severe pruritus often results in them being destroyed by scratching.

Dermatitis herpetiformis

This blistering condition is characterised by small, intensely itchy blisters occurring mainly on the extensor surfaces of knees and elbows of young adults (Fig. 24.19). The blisters are so pruritic that it is often difficult for the patient to keep one intact for the clinician to recognise. They occur at the dermo-epidermal junction, but in this case the immunoglobulin deposit is granular rather than continuous in distribution and it is almost always IgA. Curiously, although the lesions are very pruritic, the characteristic inflammatory cell seen in the infiltrates is the neutrophil polymorph and not the eosinophil. The disease is also remarkable for the fact that the response to therapy with dapsone is usually so dramatic as to be diagnostic. A significant number of these patients are shown to have some degree of gluten sensitivity (coeliac disease; Ch. 15).

Ulcers

Venous (varicose) ulcers

Treatment

Mechanical therapies are the most favoured and include: compressive bandages, which prevent the pressure transfer to the skin, or surgical removal of incompetent vessels before ulceration occurs. Local grafting of the patient’s own healthy epidermis into the ulcer with the leg elevated to reduce venous pressure is also effective.

MELANOCYTES

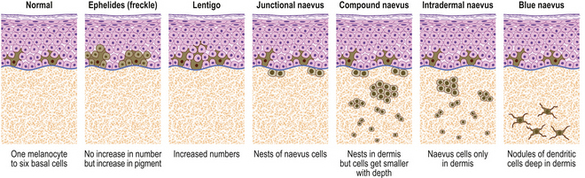

Lentigo and melanocytic naevi

Lentigos are characterised by an increase in single melanocytes in the basal epidermis. Melanocytic (naevocellular) naevi (‘moles’) are nests of melanocytes; the nest can lie:

These clinical types of naevus are all believed to be stages in the evolution of the same pathological entity (Fig. 24.20). This is not to say that any one lesion must pass through all of these stages, for their development may cease at any point.

Clinicopathological features

The last stage in the evolution of these naevi is reached when all of the junctional melanocytes have gone and only the intradermal naevus cells remain. These lesions are often pink papules or nodules because the intradermal cells produce little or no pigment and because the overlying epidermis contains only normal numbers of normally active melanocytes. It has become an intradermal naevus (Fig. 24.21) and its evolution is complete.

Malignant melanoma

The malignant tumours of melanocytic origin are called melanomas; more properly they should be called ‘melanocarcinomas’ since the term melanoma implies a benign tumour (Ch. 11), which these lesions certainly are not. In general, malignant melanomas are tumours of the skin, but since melanocytes may be found in central nervous sites such as the leptomeninges and the retina, primary malignant melanomas can arise there also.

The great clinical tragedy of malignant melanoma is that it is visible from its earliest stages and if excised before it has begun to invade the dermis it is totally curable. This is the clinical basis behind programmes encouraging self-examination and the identification of changing dysplastic (atypical) moles or early ‘thin’ melanoma. Nevertheless, each year many patients die from disseminated malignant melanoma and the incidence is increasing steadily. Clinically malignant melanoma can appear as pigmented macules, papules or nodules, and may ulcerate.

Clinicopathological features

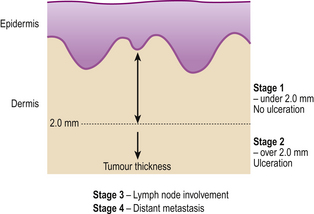

Prognosis of malignant melanoma depends predominantly on the thickness of the lesion at the time of primary excision and the presence or absence of surface ulceration. The former parameter is termed the Breslow thickness and is expressed in millimetres. The cure rate for completely excised non-ulcerated melanomas below 1mm can approach 100% and the extent of excision depends on Breslow thickness. The staging of malignant melanoma is shown in Figure 24.22.

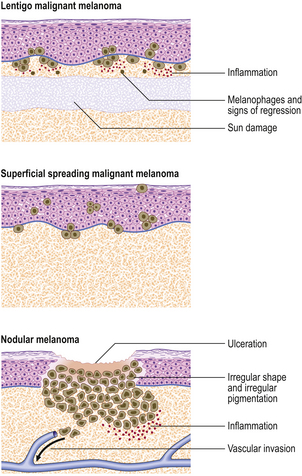

The main variants of invasive malignant melanoma are (Fig. 24.23):

Fig. 24.23 Malignant melanoma. Three different types of lesion are shown and are discussed fully in the text.

Superficial spreading melanoma (Fig. 24.24) is the commonest type in people of European descent. The epidermal spread produces a very recognisable pattern, variably described as pagetoid spread (so named because of the resemblance histologically to Paget’s disease of the nipple) or, more colourfully, as ‘buck shot scatter’ (Fig. 24.25).

Nodular melanomas retain no features to identify a pre-existing in situ lesion.

DERMAL VESSELS

The blood vessels of the dermis participate in inflammatory reactions; the details of this are identical to those seen in any organ of the body (Ch. 10). Discussed here are the phenomena affecting the skin vasculature that result in typical skin lesions. The skin lymphatics demonstrate a similar range of pathologies but these are much rarer and will not be discussed.

Telangiectasia

Telangiectasias are dilatations of capillaries often seen:

Hamartomas

Hamartomas are tumour-like malformations of tissues (Ch. 11). They consist of normal tissue elements in abnormal amounts and arrangements; in the skin, they are often called naevi or birthmarks. Naevi may contain any tissue element but in the skin the commonest are vascular naevi and 1pigmented naevi. The pigmented naevi derive from melanocytes; the vascular naevi are considered below.

Vascular naevi

Cavernous haemangiomas lie in the deep dermis or subcutaneous tissues but may be associated with an overlying capillary haemangioma. The lesion consists of large, dilated thin-walled vessels that may contain so much blood with disturbed flow characteristics that, in rare cases, consumption coagulopathy can occur (Ch. 23).

Vasculitis

Other generalised vasculitides, such as polyarteritis nodosa and Wegener’s syndrome, may cause skin lesions (Ch. 25).

ADNEXA

In skin trauma, such as burns, the regrowth of the epidermis occurs from the viable edges of the wound but it can also occur from remnants of adnexa if the original destruction was not too deep (Ch. 6). If there is full thickness destruction including the adnexa, then epidermal regrowth will occur from the edges as usual but no adnexa will develop. This implies that the adnexal remnants have the ability to differentiate to produce epidermis but that epidermal cells have lost the ability to differentiate towards the highly specialised adnexal structures of skin grafts.

Pilosebaceous system

Acne vulgaris

Acne vulgaris is so common among the adolescent population that it could nearly be viewed as a normal variant. Clinically, it is characterised by pilosebaceous units that are blocked by dark plugs of keratin, called comedones or blackheads. These blocked follicles become infected and swell up to form the characteristic pustules which may discharge on to the skin surface or rupture into the dermis, with resultant scarring.

Alopecia

Total hair loss can occur in some forms of systemic poisoning such as thallium intoxication, or from chemotherapy, in which the rapidly dividing hair cells are early victims of antimitotic agents (Ch. 5) in the same way as haemopoietic and intestinal epithelial cells.

Eccrine sweat glands

Benign (poromas and hidradenomas) and malignant sweat gland tumours occur but are rare.

Nails

The nails are affected in many general skin conditions such as psoriasis and fungal infections and may also be indicators of internal disease (p. 708). In the elderly, the great toenail may be disrupted by ill-fitting footwear or other trauma and develop into a startling hoof or horn-like protuberance (onychogryphosis) that is incapacitatingly difficult to deal with. In younger people, the direction of growth of the nail may be disturbed, from similar causes, resulting in ingrowing toenail which often needs ablation of the nail bed to cure it.

DERMAL CONNECTIVE TISSUES

Collagen and elastin

The normal effects of wear and tear on collagen and elastin are usually made good with no evidence being left that anything has happened. Eventually, however, because of the progressive accumulation of sun damage, the fibroblasts no longer secrete the ground substance in great enough quantities to repair the ravages of time and a lax, wrinkled, poorly healing skin develops as one of the unmistakable signs of the ageing process. Sun damage seems to play a large part in this process, as can be seen by comparing, clinically or histologically, areas of skin from clothed and unclothed sites. Histologically, the collagen patterns in the upper dermis are disrupted and tangled and their staining properties change (elastosis; Ch. 12); the whole skin, including the epidermis, is thinned and many fibroblasts are lost. Old skin has great difficulty in healing, not only because of the failing circulation, but also because the dermis can no longer regenerate itself or service the epidermis. Considerable time and effort can be applied in the attempt to stop or reverse these ageing processes with expensive cosmetics, but the evidence base that many achieve their desired aim is low.

Glycosaminoglycans

The best known of the diseases involving the glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) are the range of conditions in which the enzymes involved in their breakdown are defective. Because these substances are usually being metabolised and resynthesised, when their enzymatic breakdown is inhibited, they slowly accumulate, causing monstrous deformities and a host of general body symptoms. The syndromes include Hunter’s and Hurler’s diseases (Ch. 7) which used to be lumped together as gargoylism in reference to the terrible physical effects that they produce.

Mast cells

The mast cells degranulate on stimulation to release histamine, which is noxious to metazoan parasites. It also makes the skin itch and this probably results in the parasite being dislodged when the host scratches. Histamine also causes the blood vessels to dilate, allowing the various elements of the immune response to escape into the tissue and also attack the invader (Ch. 10).

Connective tissue tumours

Most dermal connective tissue tumours are benign. The most common is a benign tumour of adipose tissue (lipoma). Dermatofibroma (histiocytoma) (Fig. 24.26) usually occurs on the legs and appears to be derived from a newly discovered group of dermal cells—the dermal dendrocytes. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a malignant variant characterised by high cellularity, mitotic activity and a nodular/protuberant surface; it has a marked tendency to recur locally.

DEPOSITS

In jaundice (Ch. 16), bile pigments accumulate in the blood and eventually diffuse into the tissue. All tissues are more or less stained (except for the brain in adults) but those tissues that contain the most elastin are the most heavily stained. Elastin specifically binds bile pigments and for this reason jaundice is very obvious in the skin and even more obvious in the sclera, which contains even higher amounts of elastin than does the skin.

Other deposits in the skin include:

The skin is involved in systemic amyloidosis (Ch. 7) in the same way that other organs are affected. The skin shows raised, waxy plaques and deposition of the amorphous, eosinophilic material within the deeper dermis and subcutaneous tissue. In localised cutaneous amyloidosis there are several clinical variants, ranging from small discrete papules up to much larger, flat macules. The amyloid is located high in the skin, in the papillary dermis, and therefore causes the lesions to be more raised and to have sharper edges than those seen in systemic amyloidosis. The lesions are usually severely pruritic and therefore their appearance may be modified by the effects of scratching and rubbing. Recent studies have revealed that the amyloid in these lesions often contains modified keratin, which has descended from the epidermis and been rendered inert and packaged as amyloid in the upper dermis.

Calcium tends to precipitate in many post-inflammatory (dystrophic) situations (Ch. 7). While pilar cysts often contain areas of calcification, epidermal cysts rarely do; similarly, calcified nodules arise fairly commonly in the scrotum but are almost never encountered in the vulva. Several distinct clinical entities of dystrophic calcium accumulation are known, such as scrotal calcinosis, idiopathic calcinosis cutis, tumoral calcinosis and subcutaneous calcified nodules, in which no preceding cause can be identified. Other lesions, such as pilar cysts, scars and basal cell carcinomas, can have secondary deposits of calcium within them. One hair follicle tumour, the calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe (pilomatrixoma), is highly specific and always calcifies eventually. In all of these examples, the deposits are chemically the same and consist of calcium and phosphate.

In porphyria (Ch. 7) the various porphyrins may accumulate in different organs of the body, resulting in a variety of curious metabolic diseases. When they accumulate in the skin, as in porphyria cutanea tarda, they are often capable of producing a photosensitivity. The reason is that these molecules are similar in structure to plant chlorophyll and can generate very reactive free radicals when excited by short-wave ultraviolet light.

CUTANEOUS NERVES

Tumours of cutaneous nerves

The majority of nerve tumours are benign. They are tumours of the various cells of the nerve sheath, as mature nerves are post-mitotic and incapable of mitosis (Chs 12 and 26). The Schwann cells that support and insulate myelinated nerve fibres are capable of developing benign tumours (schwannomas). However, the other cells within the nerve sheath that seem to be more closely related to fibroblasts are the ones involved in neurofibromatosis, the congenital disease that has been identified as the cause of the Elephant Man’s deformities. These tumours are usually multiple fleshy nodules that arise throughout life and which have significant eventual malignant potential. The disease is inherited as an autosomal dominant and the gene for cutaneous neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is present on chromosome 17.

SKIN MANIFESTATIONS OF INTERNAL AND SYSTEMIC DISEASE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Commonly confused conditions and entities relating to skin pathology

| Commonly confused | Distinction and explanation |

|---|---|

| Eczema and dermatitis | Eczema is a clinical term used to describe the appearance of skin affected by dermatitis causing vesicles, scaling and exudation. |

| Spongiosis and acantholysis | Both are mechanisms of vesicle or bulla formation. Spongiosis is produced by intercellular fluid forcing apart the epidermal cells. In acantholysis, the cells are separated by destruction of the intercellular desmosomes. |

| Acanthosis and acantholysis | Both affect the prickle cell (acanthocyte) layer of the epidermis. Acanthosis means that the prickle cell layer is thickened. Acantholysis means a destruction of the intercellular desmosomes leading to cellular separation. |

| Mycosis fungoides and fungal infections | Mycosis fungoides, a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, has absolutely nothing to do with fungal infections; the nomenclature is misleading. The lesions are clinically and pathologically different. |

| Pemphigus and pemphigoid | Pemphigus and pemphigoid are both immune-mediated bullous disorders. In pemphigus vulgaris there is damage to the prickle cell layer of the epidermis, whereas in bullous pemphigoid the damage is located at the dermo-epidermal junction. |

| Herpes virus, herpes gestationis and dermatitis herpetiformis | The virus inherits its name from the herpetic (clusters of small vesicles) rash it produces, similar to the clinical features of herpes gestationis and dermatitis herpetiformis, neither of which has any causal connection with herpes virus. |

| Lichenoid and psoriasiform | A lichenoid reaction is characterised by basal cell damage resulting in a low rate of epidermal cell renewal; for example, it is a feature of lichen planus. A psoriasiform epidermal reaction is characterised by an increased rate of epidermal cell renewal, as in psoriasis. |

Elder D.. Lever’s histopathology of the skin, 9th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 2005.

LeBoit P., Burg G., Weedon D., Sarasin A.. World Health Organization classification of tumours. Lyons: Skin tumours. IARC Press, 2006.

McKee P.H., Calonje E., Granter S.R.. Pathology of the skin with clinical correlations, 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2005.

Miller A J, Mihm 2006 M Mechanisms of disease. Melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine 355:51–64.

Naeyaert J.M., Brochez L.. Dysplastic naevi. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349:2233-2240.

Rubin A.I., Chen E.H., Ratner D.. Basal cell carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353:2262-2269.

Slater D.N., McKee P.H.. Minimum dataset for the histopathological reporting of common skin cancers. London: Royal College of Pathologists; 2002. pp 1–25

Thompson J.F., Scolyer K.A., Kefford R.F.. Cutaneous melanoma. Lancet. 2005;365:687-703.

Weedon D.. Skin pathology, 2nd edn. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2002.

Benign neoplasm (papilloma).

Benign neoplasm (papilloma).  Malignant neoplasm (carcinoma).

Malignant neoplasm (carcinoma).